Generation Z and Travel Motivations: The Impact of Age, Gender, and Residence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Travel Motivation and the Travel Career Pattern (TCP) Theory

2.2. Youth Travel and Generation Z

2.3. Demographic Factors and Travel Motivations

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

- Yi = dependent variable (gender, age and residence);

- Xi = independent variable (motivational factors to travel);

- Β = intercept;

- εi = error term (the difference between the observed and predicted value for observation).

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Description of Participants

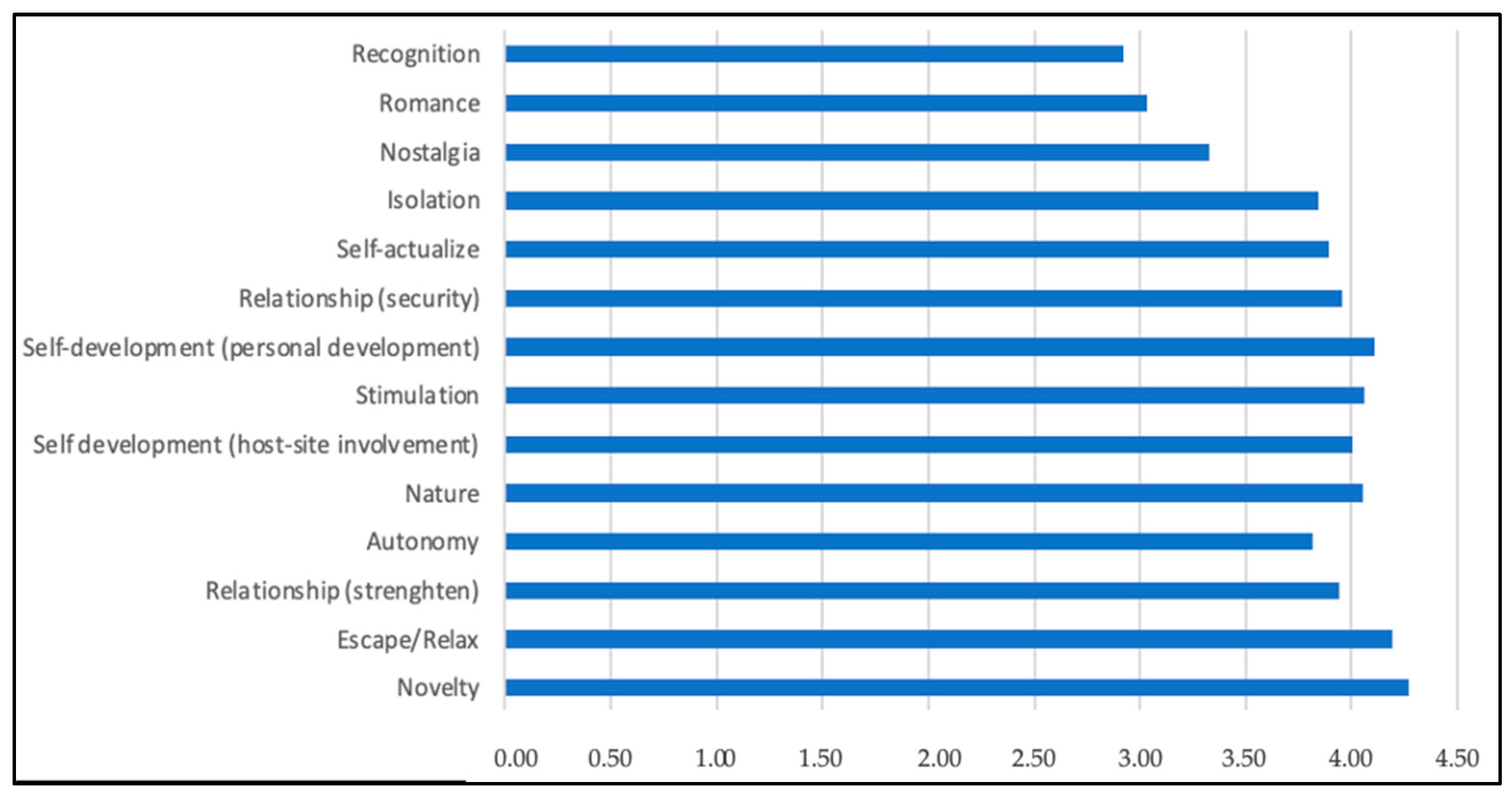

4.2. Descriptive Statistics of Items

4.3. Relationship Between Motivational Factors and Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants

5. Discussion of Findings

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Begashe, B. A., Mgonja, J. T., & Matotola, S. (2024). Tanzania’s repeat tourists: Unraveling choice of attractions patterns through demographic perspectives. Tourism Critiques: Practice and Theory, 5(1), 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, F. (2015). Young Tourists and Sustainability. Profiles, Attitudes, and Implications for Destination Strategies. Sustainability, 7, 14042–14062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagnaro, E., & Staffieri, S. (2015). A study of students’ travellers values and needs in order to establish futures patterns and insights. Journal of Tourism Futures, 1(2), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E., Lee, A., Byeon, E., & Lee, S. M. (2015). Role of motivation in the relation between perfectionism and academic burnout in Korean students. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W., Tian, R., & Chiu, D. K. (2024). Travel vlogs influencing tourist decisions: Information preferences and gender differences. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 76(1), 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D., & Tisdell, C. (2002). Gender and differences in travel life cycles. Journal of Travel Research, 41(2), 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J. L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(1), 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S., & Dedeoğlu, B. B. (2019). Psychological factors affecting the behavioral intention of the tourist visiting Southeastern Anatolia. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 2(4), 425–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, C., & Ritchie, B. W. (2020). Understanding travel behavior: A study of school excursion motivations, constraints and behavior. Journal of Travel Research, 59(7), 1228–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G. M. S. (1981). Tourist Motivation: An Appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research, 8(2), 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeri, L., Armenski, T., Tesanovic, D., Bradić, M., & Vukosav, S. (2014). Consumer behaviour: Influence of place of residence on the decision-making process when choosing a tourist destination. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 27(1), 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, I., Lei, S. I., & Wassler, P. (2020). Digital free tourism—An exploratory study of tourist motivations. Tourism Management, 79, 104098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, R., Gula, I., & Walcher, D. (2016). Open tourism: Open innovation, crowdsourcing and co-creation challenging the tourist industry. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X., Qiu, H., Hsu, C., & Liu, Z. (2015). Comparing motivations and intentions of potential cruise passengers from different demographic groups: The case of China. Journal of China Tourism Research, 11(4), 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foot, D. (2004). Leisure futures: A change in demography? In K. Weiermair, & C. Mathies (Eds.), The tourism and leisure industry: Shaping the future (pp. 21–33). The Haworth Hospitality Press. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, T., & Hoefel, F. (2018). True Gen’: Generation Z and its implications for companies (p. 12). McKinsey & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, S., Grace, D., & King, C. (2014). The generation effect: The future of domestic tourism in Australia. Journal of Travel Research, 53(6), 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X., Lewis, B., Li, Y., Wang, Z., Sheng-nan, W., & Li-Min, D. (2015). Travel motivations of domestic tourists to Changbai Mountain biosphere reserve in Northerneastern China: A comparative study. Journal of Mountain Science, 12(6), 1582–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2016). The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(9), 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. (2021). Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(7), 1021–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V. C. S., Qu, H., & Chu, R. (2001). The relationship between vacation factors and socio-demographic and travelling characteristics: The case of Japanese leisure travellers. Tourism Management, 22(3), 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, J. M. M. (1965). The holiday: A study of social and psychological aspects with special reference to Ireland. The Tavistock Institute of Human Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Hysa, B., Karasek, A., & Zdonek, I. (2021). Social media usage by different generations as a tool for sustainable tourism marketing in society 5.0 idea. Sustainability, 13(3), 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimias, A., Mitev, A., & Michalko, G. (2016). Demographic characteristics influencing religious tourism behaviour: Evidence form a Central-Eastern European country. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 4(4), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1982). Toward a social psychological theory of tourism motivation: A rejoinder. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(2), 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaraj, C., & Bindu, T. (2013). An analysis of push and pull travel motivations of domestic tourists to Kerala. International Journal of Management and Business Studies, 3, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, N. S., & Mkwizu, K. H. (2020). Demographic factors and travel motivation among leisure tourists in Tanzania. International Hospitality Review, 34(1), 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. Y., & Park, S. (2019). Rethinking millennials: How are they shaping the tourism industry? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(1), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & Lehto, X. (2013). Projected and perceived destination brand personalities: The case of South Korea. Journal of Travel Research, 52, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & Prideaux, B. (2005). Marketing Implications arising from a comparative study of international pleasure tourist motivations and other travel related characteristics of visitors to Korea. Tourism Management, 26(3), 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. (2002). Comparative analysis of tourist motivations by nationality and destinations. Tourism Management, 23(3), 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T., & Hsu, C. H. C. (2006). Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tourism Management, 27, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C., & Lee, E. H. (2024). Evaluation of urban nightlife attractiveness for Millennials and Generation Z. Journal of Tourism and Leisure Studies, 30(2), 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmetyinen, A., Dimitrovski, D., Nieminen, L., & Pohjola, T. (2016). Cruise destination brand awareness as a moderator in motivation-satisfaction relation. Tourism Review, 71(4), 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., & Cai, A. L. (2013). A sub cultural analysis of tourism motivations. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(1), 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y., & Deng, J. (2008). The new environmental paradigm and nature-based tourism motivation. Journal of Travel Research, 46, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A., Chow, A., Cheung, L., Lee, K., & Liu, S. (2018). Impacts of tourists’ socio demographic characteristics on the travel motivation and satisfaction: The case of protected areas in South China. Sustainability, 10(10), 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiurro, M., & Brandão, F. (2024). Motivations, needs, and perceived risks of middle-aged and senior solo travelling women: A study of brazilian female travellers. Journal of Population Ageing, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C., Mohsin, A., & Lengler, J. (2018). A multinational comparative study highlighting students’ travel motivations and touristic trends. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 10, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrin, I., Turșie, C., & Lupșa Matichescu, M. (2024). Exploring sustainable tourism through virtual travel: Generation Z’s perspectives. Sustainability, 16(24), 10858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F., & Uysal, M. (2008). Effects of gender differences on perceptions of destination attributes, motivations, and travel values: An examination of a nature-based resort destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(4), 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, N., Wien, C., & Reisinger, Y. (2017). Push and pull escape travel motivations of Emirati nationals to Australia. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 11(3), 274–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieczkowski, Z. (1990). The world trends in tourism and recreation. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi, Y., & Wada, Y. (2025). Effects of past tourism experience on the current travel motivations of Japanese travellers. International Journal of Tourism Research, 27(2), e2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkwizu, K. H. (2018). Analysis of sources of information and income of domestic tourists to national parks in Tanzania. ATLAS Tourism and Leisure Review, 2018(2), 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, S. (2018). Tourism and the new generations: Emerging trends and social implications in Italy. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G., Morrison, A., Pearce, P., Lang, C., & O’Leary, J. (1996). Understanding vacation destination choice through travel motivation and activities. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 2(2), 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021, March 26). Chart: How gen Z employment levels compare in OECD countries. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/03/gen-z-unemployment-chart-global-comparisons/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Oktadiana, H., & Agarwal, M. (2022). Travel career pattern theory of motivation. In D. Gursoy, & S. Çelik (Eds.), Routledge handbook of social psychology of tourism (pp. 76–86). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodorou, A. (2006). Managing tourism destinations. Edward Elgar Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P. L., & Caltabiano, M. L. (1983). Inferring travel motivation from travelers’ experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 22(2), 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P. L., & Lee, U. L. (2005). Developing the travel career approach to tourism motivation. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M., & Gomes, S. (2023). Generation Z as a critical question mark for sustainable tourism—An exploratory study in Portugal. Journal of Tourism Futures, 10(3), 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preko, A., Doe, F., & Dadzie, S. A. (2019). The future of youth tourism in Ghana: Motives, satisfaction and behaviour intentions. Journal of Tourism Futures, 5(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pricope Vancia, A. P., Băltescu, C. A., Brătucu, G., Tecău, A. S., Chitu, I. B., & Duguleană, L. (2023). Examining the disruptive potential of Generation Z tourists on the travel industry in the digital age. Sustainability, 15, 8756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G., Huang, S., & Vorobjovas-Pinta, O. (2024). Seeking tourism in a social context: An examination of Chinese rural migrant workers’ travel motivations and constraints. Leisure Studies, 43(4), 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. (2015). The new global nomads: Youth travel in a globalizing world. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(3), 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K., & Schänzel, H. A. (2019). A tourism influx: Generation Z travel experiences. Journal of Tourism Futures, 5(3), 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simková, E., & Holzner, J. (2014). Motivation of Tourism Participants. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 159, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snepenger, D., King, J., Marshall, E., & Uysal, M. (2006). Modeling Iso-Ahola’s motivation theory in the tourism context. Journal of Travel Research, 45(2), 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorović, N., & Jovičić, D. (2016). Motivational factors of youth tourists visiting Belgrade. Journal of the Geographical Institute “Jovan Cvijic”, 66(2), 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S., & Crompton, J. (1990). Attitude determinants in tourism destination choice. Annals of Tourism Research, 17, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J., & Larsen, J. (2012). The tourist gaze 3.0. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, U. (2006). Leisure—Meaning and Impact on Leisure Travel Behavior. Journal of Services Research, 6. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1615363 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Wade, D. J., Mwasaga, B. C., & Eagles, P. F. J. (2001). A history and market analysis of tourism in Tanzania. Tourism Management, 22(1), 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasekera, D., & Assella, A. P. N. (2025). How does immersion affect the travel intention of Gen Z tourists? The mediating role of happiness. Tourism Psychology Review, 11(1), 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, S., Wahyudi, W., Kusuma, C., & Sugiano, E. (2018). Travel motivation of Indonesian seniors in choosing destination overseas. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Review, 12(2), 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A., & Lysonski, S. (1989). A general model of traveller destination choice. Journal of Travel Research, 27(4), 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). (2008). Youth travel matters-understanding the global phenomenon of youth travel. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284412396 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- WYSE Travel Confederation. (2023, March 8). International youth travel poised for continued stability and growth in volume and expenditure. WYSE News. Available online: https://www.wysetc.org/2023/03/international-youth-travel-poised-for-continued-stability-and-growth-in-volume-and-expenditure/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Yamagishi, K., Canayong, D., Domingo, M., Maneja, K. N., Montolo, A., & Siton, A. (2024). User-generated content on Gen Z tourist visit intention: A stimulus-organism-response approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(4), 1949–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N., & Halpenny, E. (2019). The role of cultural difference and travel motivation in event participation: A cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 10(2), 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X., O’leary, J., Morrison, A., & Hong, G. (2000). A cross-cultural comparison of travel push and pull factors: United Kingdom vs. Japan. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 1(2), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A., Amin, I., & Santos, J. C. (2018). Tourists’ motivations to travel: A theoretical perspective on the existing literature. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 24, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung-Kun, S., Kuo-Chien, C., & Yuan-Feng, S. (2015). Market segmentation of international tourists based on motivation to travel: A case study of Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(8), 862–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Ouyang, Y., & Tavitiyaman, P. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Generation Z employees’ perception and behavioral intention toward advanced information technologies in hotels. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(2), 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X., & Wang, Y. (2024). Social support and travel: Enhancing relationships, communication, and understanding for travel companions. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(4), e2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 176 | 58.2% |

| Male | 115 | 38.2% |

| Other | 11 | 3.6% |

| Age | ||

| 18–20 years | 147 | 48.5% |

| 21–23 years | 86 | 28.4% |

| 24–26 years | 40 | 13.2% |

| 27–28 years | 30 | 9.9% |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 205 | 67.7% |

| Employee | 69 | 22.8% |

| Self-Employed | 15 | 4.6% |

| Unemployed | 15 | 5% |

| Residence | ||

| Urban area | 203 | 67% |

| Rural area | 60 | 19.8% |

| Beach area | 28 | 9.2% |

| Mountain area | 3 | 1% |

| Island | 9 | 3% |

| Items | Mean (M) | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Novelty | 4.27 | 0.995 |

| NOV1 | 4.45 | 0.998 |

| NOV2 | 4.23 | 0.982 |

| NOV3 | 4.03 | 1.042 |

| NOV4 | 4.37 | 0.957 |

| Escape/relax | 4.19 | 1.030 |

| ES1 | 4.17 | 1.039 |

| ES2 | 4.15 | 1.063 |

| ES3 | 4.09 | 1.053 |

| ES4 | 4.35 | 0.964 |

| Relationship (strengthen) | 3.94 | 1.126 |

| REL1 | 3.89 | 1.088 |

| REL2 | 3.87 | 1.222 |

| REL3 | 4.06 | 1.067 |

| Autonomy | 3.81 | 1.111 |

| AUT1 | 3.81 | 1.107 |

| AUT2 | 3.88 | 1.120 |

| AUT3 | 3.75 | 1.105 |

| Nature | 4.06 | 1.040 |

| NAT1 | 4.22 | 0.989 |

| NAT2 | 3.89 | 1.091 |

| Self-development (host-site involvement) | 4.00 | 1.035 |

| SD1 | 4.08 | 1.028 |

| SD2 | 4.19 | 0.999 |

| SD3 | 3.96 | 1.074 |

| SD4 | 4.11 | 0.988 |

| SD5 | 3.67 | 1.088 |

| Stimulation | 4.06 | 1.066 |

| ST1 | 3.98 | 1.059 |

| ST2 | 4.22 | 1.009 |

| ST3 | 4.04 | 1.084 |

| ST4 | 3.99 | 1.113 |

| Self-development (personal development) | 4.11 | 1.042 |

| PD1 | 4.18 | 0.988 |

| PD2 | 4.13 | 1.062 |

| PD3 | 4.08 | 1.040 |

| PD4 | 4.05 | 1.079 |

| Relationship (security) | 3.96 | 1.098 |

| RELS1 | 4.20 | 1.036 |

| RELS2 | 4.10 | 1.095 |

| RELS3 | 3.82 | 1.128 |

| RELS4 | 3.70 | 1.131 |

| Self-actualize | 3.90 | 1.138 |

| SA1 | 3.98 | 1.087 |

| SA2 | 4.00 | 1.119 |

| SA3 | 3.80 | 1.138 |

| SA4 | 3.80 | 1.207 |

| Isolation | 3.85 | 1.103 |

| ISOL1 | 4.09 | 1.051 |

| ISOL2 | 3.91 | 1.043 |

| ISOL3 | 3.54 | 1.214 |

| Nostalgia | 3.33 | 1.222 |

| NOS1 | 3.18 | 1.236 |

| NOS2 | 3.48 | 1.207 |

| Romance | 3.04 | 1.364 |

| ROM1 | 3.16 | 1.362 |

| ROM2 | 2.91 | 1.365 |

| Recognition | 2.92 | 1.306 |

| REC1 | 3.58 | 1.201 |

| REC2 | 2.81 | 1.362 |

| REC3 | 2.69 | 1.331 |

| REC4 | 2.60 | 1.328 |

| Gender | Age | Residence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p-Value | Coefficient | p-Value | Coefficient | p-Value | |

| Novelty | 0.201 | 0.000 | −0.125 | 0.037 | −0.098 | 0.008 |

| Escape/relax | 0.163 | 0.008 | −0.158 | 0.009 | −0.186 | 0.009 |

| Relationship (strengthen) | 0.180 | 0.002 | −0.114 | 0.002 | −0.205 | 0.007 |

| Autonomy | 0.118 | 0.291 | −0.096 | 0.001 | 0.041 | 0.007 |

| Nature | −0.116 | 0.002 | −0.150 | 0.006 | −0.065 | 0.007 |

| Self-development (host-site involvement) | 0.114 | 0.381 | −0.125 | 0.003 | 0.100 | 0.003 |

| Stimulation | 0.216 | 0.001 | −0.123 | 0.140 | −0.155 | 0.009 |

| Self-development (personal development) | 0.236 | 0.000 | −0.121 | 0.003 | −0.131 | 0.008 |

| Relationship (security) | 0.121 | 0.003 | −0.138 | 0.350 | −0.092 | 0.006 |

| Self-actualize | 0.122 | 0.008 | −0.106 | 0.076 | 0.052 | 0.008 |

| Isolation | 0.131 | 0.034 | −0.096 | 0.243 | −0.055 | 0.007 |

| Nostalgia | 0.154 | 0.008 | −0.124 | 0.180 | −0.109 | 0.009 |

| Romance | 0.153 | 0.013 | −0.193 | 0.001 | −0.106 | 0.003 |

| Recognition | 0.185 | 0.001 | −0.120 | 0.114 | −0.088 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marques, J.; Gomes, S.; Ferreira, M.; Rebuá, M.; Marques, H. Generation Z and Travel Motivations: The Impact of Age, Gender, and Residence. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020082

Marques J, Gomes S, Ferreira M, Rebuá M, Marques H. Generation Z and Travel Motivations: The Impact of Age, Gender, and Residence. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(2):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020082

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarques, Jorge, Sofia Gomes, Mónica Ferreira, Marina Rebuá, and Hugo Marques. 2025. "Generation Z and Travel Motivations: The Impact of Age, Gender, and Residence" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 2: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020082

APA StyleMarques, J., Gomes, S., Ferreira, M., Rebuá, M., & Marques, H. (2025). Generation Z and Travel Motivations: The Impact of Age, Gender, and Residence. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020082