1. Introduction

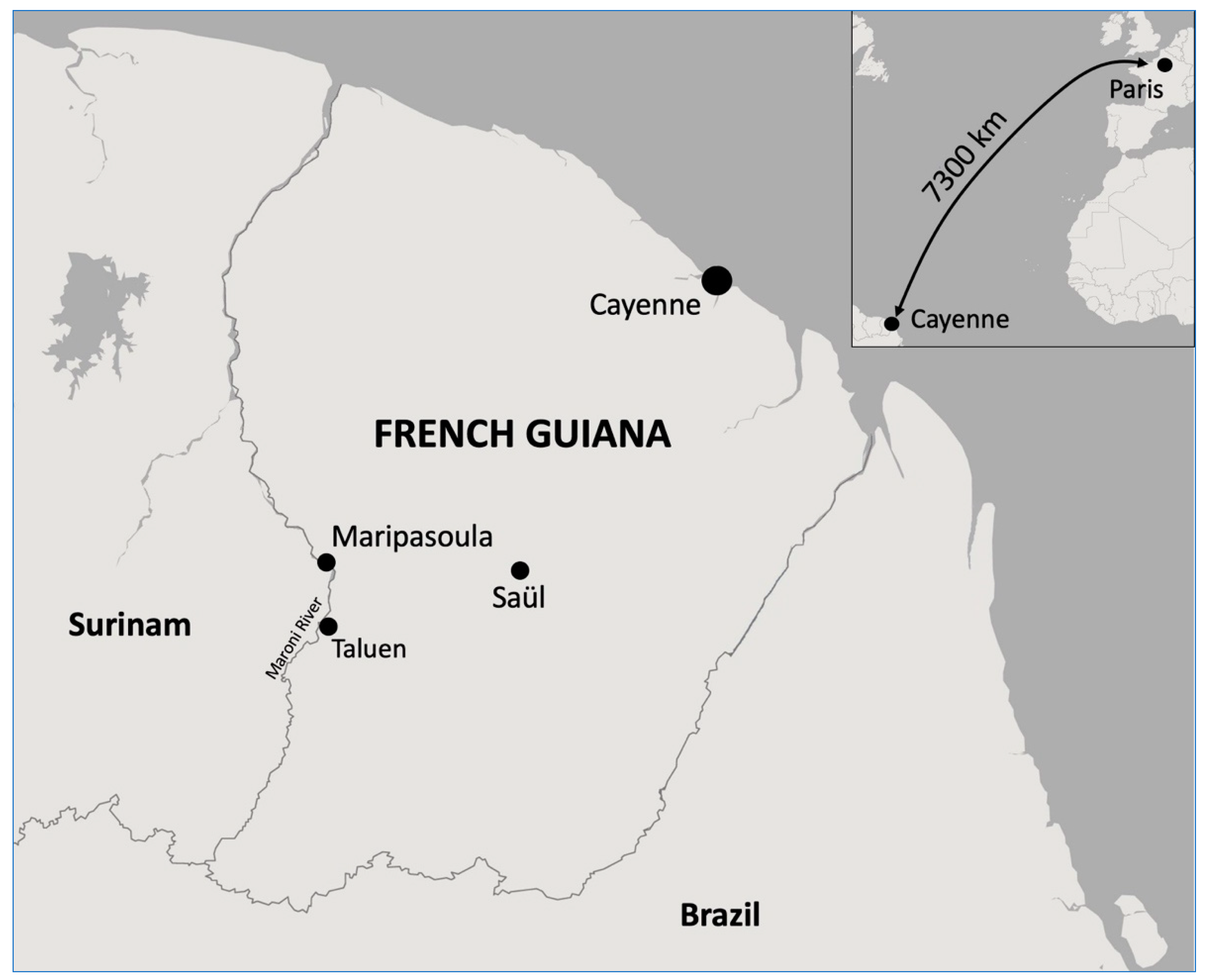

The Haut-Maroni region in French Guiana (

Figure 1), only accessible by canoe or plane, constitutes a low-density inhabited space that is subject to a governance regime whose decision-making center is more than 7300 km away in “metropolitan” France. It is a territory whose peripheral identity is both geographical and political given its distance from locations of power and communication. The creation of a national park in this region in 2007 was the result of more than 10 years of negotiations that were made necessary by the difficulties of establishing a territorial co-management protocol with local inhabitants, the Indigenous Wayana and the Bushinengués Aluku [

1].

The Charter of the Guiana Amazonian Park is currently being renegotiated. The territory’s initial management, based on the preservation of natural resources and their protection against illegal gold panning, is accompanied by new territorialization processes that are linked to emerging tourism practices. Territorialization thus draws our attention to spaces as products of social processes and practices; it is the expression of different types of power. We agree with Melé (2009: 46), who remarked on the need “to leave open the notion of territorialization and to consider it both in the sense of identification/production of delimited spaces, of dissemination of a ‘territorial’ vision of the relationship with the space of the populations, and of appropriation by individuals or groups of more or less strictly delimited spaces” [

2]. Thus, two other territorialization projects are superimposed on tourism activities in a protected area and on local stakeholders’ process of territorialization (the territory as it is perceived, experienced by these same stakeholders): the first is an ecological project, of which the protected area is the clearest manifestation; the second is tourism, with its new key places, its stakeholders, and its flux [

3]. In many areas, the construction of new territories has accelerated and the actors involved have shifted. However, not all actors have the same status and do not have the power to produce territory [

4]. The territorialization by and for tourism, in addition to that resulting from the establishment of protected areas, are good examples.

Tourism is one of today’s most frequently used means of justifying and legitimizing conservation via the creation of protected areas. However, this tourism/protected area synergy inevitably has negative effects both on the ecosystem and on the social system in which it is inserted, whether because of visitors or infrastructure, or new institutional arrangements that modify the socio-political and economic dynamics of the concerned regions. Tourism thus contributes to the construction of territories. As Di Méo (1998: 225) suggests, “by shaping real territorial products, modern tourism contributes to creating images, but also infrastructure networks, flows that in turn produce or reproduce territory” [

4]. For Boukhris (2012), by promoting the emergence of tourist places, the tourist imaginary invests in geographical space and participates in its material and symbolic production [

5]. We often forget, moreover, that tourism is a form of natural resource exploitation and that it has lasting impacts on the territory and on the way local communities interact with their environment.

Focusing on the concept of region, Saarinen (2004) considers the tourist destination to be a historical unit that evolves via its interaction with other socio-spatial units at different levels [

6]. In a way, these destinations are socio-spatial realities that are produced and represented in a specific way. Conceptualized in this manner—and even more so when associated with the notion of territory—the destination cannot be understood as simply a physical entity that is well delimited through administrative divisions or concrete physical markers. As the author reminds us, “[t]he critical interpretations of representations of destinations, commodification and touristic geographies stress the need to analyze the processes and discourses by which the spaces of tourism are produced” [

6] (p. 174). In this view, tourism in protected areas cannot be presented as a homogeneous phenomenon. An intervention by and for the touristic development of the territory leads to changes that affect, on the one hand, relationships between actors and, on the other hand, relationships between these actors and their environment.

However, developing tourist activities no longer only faces governance or geographical challenges, they now also include the appearance of the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in early 2020, responsible for the worldwide proliferation of COVID-19. With a toehold in French Guiana since April 2020, the virus eventually reached the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region, i.e., the area under study (

Figure 2). Governance issues during the process of touristification cannot be divorced from the health challenges posed in the context of Indigenous living spaces. Indeed, even if this particular virus were to be eliminated, or at the very least controlled, structural and cultural factors mean that Indigenous communities in remote and isolated environments remain vulnerable to health risks related to tourist mobility [

7].

So far, tourist practices in the Guiana Amazonian Park have been very low intensity, but they are expected to intensify as part of a local economic development strategy put forward by different metropolitan decision makers and Guyanese groups. Putting nonessential mobility on hold during the pandemic halted, for a certain amount of time, the process of the tourist territorialization of the living space of local populations who are in territorial relations with the Guiana Amazonian Park through the Park Charter [

1,

8]. The suspension of already marginal tourist practices in the Maripasoula region represents an opportunity to take a renewed interest in the paradigm of tourism as a “catalyst for development” at a time when the recovery of the sector is just beginning [

9].

There are few studies about protected areas, biodiversity and governance issues in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], and most have partially or even completely left “tourism” out of their analysis. Those dealing more particularly with the creation of the Guiana Amazonian Park [

16,

17,

18,

19] have not offered an in-depth analysis of tourism development in the context of the establishment of a protected area. Only Breton (2007) and Sarrasin et al.’s (2016) analyses of nature tourism development through the lens of adaptive co-management tackle the subject and have a real understanding of the issues related to tourism development in the region [

1,

20]. Our article and its focus on territorial governance, as it relates to the creation of a protected area, is a direct contribution to the literature on tourism in French Guiana.

Natural resource development is often confronted with a variety of competing land uses where the imperatives of rapid economic growth often take precedence over sustainability considerations. In many cases, local communities find themselves being unable to access land that provides a substantial portion of their livelihoods. This issue is currently the subject of a body of academic study from a wide range of fields and disciplines, including those on forest retreat, conservation and protected areas, agricultural expansion and agrarian transition, land and resource grabbing, and exclusion [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Nature tourism, a rapidly expanding economic activity sector that is favoured by many organizations, governments and communities as the main solution to land management problems, is being questioned because of the conflicts of use it generates at various levels and the radical changes in local populations’ subsistence activities it often requires [

26,

27,

28]. Often presented as a panacea for the preservation of resources and their sustainable use, the development of tourism in natural areas has had mixed results in recent years. It is struggling to promote more “ecological” practices that frame the development of territories. Since current management models have difficulty taking into account the plurality of actors and interests at work in the territories concerned, we are witnessing a proliferation of conflicts of use, as presented in our case study.

More specifically, this article focuses on the processes of territorialization of local populations’ living space that the governance regime in French Guiana created, and its effects on the production of a tourist space in the context of sparsely populated regions. Along with the National Forestry Office (Office National des Fôrets), the Regulated Access Zone (Zone d’accès contrôlée), and the Zones of Common Use Rights (Zones de droits d’usage collectifs), the Guiana Amazonian Park will be analyzed as a territorialization agent with mechanisms that influence the development of tourism in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni zone. Through these governance regimes’ territorial framework, we wish to better understand the nature of the territorial dynamics that exist between the processes of the global production of tourist areas and those related to local populations’ management of living space. The objective is to better understand the challenges involved in touristifying a peripheral territory, what Le Tourneau (2020) refers to as a Sparsely Populated Region [

29], to answer the following question: What are the territorial dynamics of governance that underlie the production of a tourism space in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region?

After a brief description of our methodological and theoretical framework, the article outlines the regional and local context of tourism in French Guiana. It also offers a territorial description of the different inclusion criteria for Sparsely Populated Regions in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region (i.e., low population density, incomplete state territorial control, remoteness in terms of mobility, and the presence of societies with distinct ways of life) which will be linked to the concrete tourist practices in this territory. The processes of territorialization will then be analyzed through the different governance regimes that the French regime set up in order to understand how they fit into the production of a tourist space. Next, we will address the stakes and the challenges of tourism development of the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni space. Finally, a reflection on the future of tourism in this region will be proposed, particularly with regard to the colonial governance regimes vis-à-vis the important Indigenous populations in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

Participant and non-participant observation initiatives were undertaken throughout the stay (excursions on the Maroni, hiking in the forest, walks in the different living spaces, etc.). This approach made it possible to better understand the territorial dynamics that tourists must deal with in Sparsely Populated Areas. The touristification of the living space of the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region has been undertaken in part by groups of actors who have not traveled the territory. To understand the logistical implications and mobility challenges specific to a Sparsely Populated Region, we needed to observe and experience the territory.

In addition to written sources, our methodological approach is based on both interviews with key actors and participant and non-participant observation, conducted during 27 days of field research in April 2019. Eighteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with individuals who provide services to tourists, and so are directly involved in tourist activities, and stakeholders linked to territorial and tourist management, who are thus indirectly involved in tourist activities (see

Table 1). We initially targeted employees of the Guiana Amazonian Park involved in implementing the Charter. We then applied the “snowball” technique to identify and recruit other participants. This method targeted those with the potential to provide additional insight [

30]; thus, we prioritized stakeholders with recognized knowledge and expertise in tourism who were involved both in providing services and in the direct or indirect management and development of the tourism industry.

3. Political Geography of Tourism

Initially based on the geographical characteristics of the territories, tourism activity relies on and creates rivalries of power over the spaces that are visited and occupied. Tourism activity also frames the convergence of several issues that use political geography as an analytical framework [

31,

32,

33]. In addition to contributing directly to the appropriation of space through territorial planning, or the structuring of relations between the center (where political and administrative decisions are made) and the periphery (where fewer decisions are made and where services partially exist or are absent, as we will see in the discussion of Sparsely Populated Regions), the tertiary sector, to which the tourism industry belongs, implies continuous demands to reorient the natural and socio-cultural resources of the living space toward tourist activity [

8,

34].

Given this context, in terms of land use, there is a conflict between tourist activity and other practices that serve to consolidate local populations’ living space (agriculture, hunting, fishing, etc.). This conflict is shaped by the use of power, which constitutes a founding element in the production of territory. For Raffestin (1980), space becomes territory through a dynamic of inclusion/exclusion, which is mediated by struggles between groups of stakeholders, including the state [

35]. This is a relational process. As for Sack (1986), it is the state that territorializes, that is, that organizes, fixes or excludes groups of actors in the territory [

36]. This is a formal process. The production of a tourist territory is the result of a struggle between the relational power linked to the capacity of local/regional stakeholders in the periphery to take charge of the territory and the formal power that state stakeholders from the center try to impose.

A political geography of tourism in French Guiana that analyzes the agents and mechanisms of territorialization allows us to understand the logic of unequal territorial relations brought about by power relations (political and economic) between the French state and groups of territorial actors in Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni. We embrace a critical approach to political geography in order to identify and analyze the main challenges for the French Guyanese territory, and particularly the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni zone, that the development of tourism poses.

4. Tourism in French Guiana

In the past, tourism has demonstrated a strong capacity for resilience in the face of geopolitical and economic circumstances, particularly following the events of September 2001 or in the wake of the “subprime” economic crisis of 2008–2009 [

37]. The current public health crisis has been much more damaging to tourism than any other event since the end of the Second World War [

38]. Regional inequalities regarding access to the vaccine favor the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants, which make global immunity unlikely in the short term [

39] and increase the probability of widespread infection, rendering a resumption of global mobility comparable to the pre-pandemic period far from certain. The conflict in Ukraine also actively contributes to this instability.

In any case, it is unclear how the tourism industry in French Guiana will react to a return to the necessary conditions for international tourism growth. Indeed, tourism in this peripheral territory is a relatively marginal activity compared to tourism in metropolitan France. This is also apparent when we compare Guyanese tourism to the South Caribbean region.

Statistics relating to tourist activity in French Guiana are still poorly managed. According to the participant from the French Guiana Tourism Committee, the various tourism stakeholders must produce quality statistics that can be used to guide tourism development (interview #1022). To lighten the text, only the number will be provided for the rest of the references to the interviews. A statistics committee was finally set up in March 2021, but it is still too early to take advantage of this new tool [

40]. Nevertheless, a recent report produced by Bouchaut-Choisy (2018) presents the main characteristics of tourism in French Guiana [

41]. According to the author, approximately 100,000 travelers visited the department in 2017. Of these, 60% were from mainland France, 27% were from the French West Indies, and 13% were from the rest of the world, including 1% from neighboring Brazil. It should be noted that 33% of arrivals were affinity tourists, primarily visiting relatives or friends. This and professional tourism represent approximately 85% of all travelers. The proportion of purely recreational visitors therefore remains negligible.

As the basis for an analysis of overnight stays, the statistics available on the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies website (INSEE) make it possible to assess the relative weight of tourism in this territory [

42]. The total volume represents 453,000 overnight stays compared to 219 million in metropolitan France. As a proportion of overnight stays/population, France has 2.28 times more overnight stays than its overseas department and region. In addition, according to INSEE, before the pandemic slowed tourism, the number of overnight stays increased by 32% between 2011 and 2019; 2018 alone accounts for 16% of this increase. According to more recent data, the pandemic caused the number of overnight stays to drop by 41.2% between April 2020 and August 2021 [

43]. Successive waves of infection since then make any prospect of recovery difficult to predict.

The fact that tourism in French Guiana is not comparable to that in mainland France is not surprising considering its distance from the main sources of tourism. We can better grasp the mixed nature of French Guiana’s appeal by comparing it with a similar destination. For instance, Costa Rica, which offers much the same tourist experience, attracted just over 74,000 French visitors in 2018 out of a total of 3,000,000 [

44]. Several factors explain this disparity, including aggressive communication campaigns, a favourable quality/price ratio in Costa Rica, infrastructure quality, and the superior service on offer in this Central American country. Moreover, other structural elements work against the emergence of French Guiana as a nature destination despite the development efforts made by the various local and metropolitan partners in recent years [

45,

46].

Despite certain outstanding attractions, including cultural diversity and natural assets that could support the emergence of an ecotourism sector, the development of tourism in the territory is stagnating and the “destination” remains on the sidelines of regional tourist circuits. We hypothesize that this situation is not unrelated to the fact that the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni zone has characteristics of a Sparsely Populated Region, limiting the impact of tourism development initiatives. Low population density, problems with territorial controls, remote axes of mobility, and the presence of societies with distinct lifestyles are all characteristics of Sparsely Populated Regions, and help to explain this region’s difficulty in emerging as a tourist destination.

5. Sparsely Populated Regions

Le Tourneau (2020) developed the Sparsely Populated Region concept with the intention of refining understandings about remote regions in order to distinguish them from other designations for poorly adapted territories, i.e., the hinterland, the bush, wide open spaces, and the like. Indeed, these notions do not fully characterize the widespread sprinkling of small population groups, as defined by the author [

29]. More specifically, Sparsely Populated Regions are distinguished from other types of territories by four inclusion criteria: low density, incomplete state control, isolation and remoteness from axes of mobility, and the presence of distinct societies with widely varying lifestyles.

The next section first offers an overview of these inclusion criteria to show how the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region meets them. Then, through a description of mobility in this region, we will show how the notion of a Sparsely Populated Region fits into tourist practice. Lastly, we will explore the different challenges that travel in this type of territory entails from the point of view of a traveler.

5.1. Low Density

An explanation of Low Density cannot be reduced to discussing administrative units because the relationship between the population and a given area is not sufficient in order to highlight the spatial reality in this type of territorialization. In addition to low population density, inhabitants of remote regions must also find a way to access efficient mobility networks that could empower them not only to implement territorial development, including a viable labor market, but also non-deficit public and private services. This situation still applies despite the presence of higher density units, for example, towns. Finally, low population density also means that a large proportion of the territory is controlled by the state, thus providing a leverage for the decision-making power of external stakeholders.

The Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region typifies the demographic configuration that is specific to Sparsely Populated Regions. For instance, the community of Maripasoula—which includes the town of Maripasoula and various villages along the Haut-Maroni—has a population of 13,351 inhabitants [

42], who are scattered over an area of 18,360 km

2, which is equivalent to a population density of 0.72 people per km

2. Considering that nearly half of the population lives in the town, the rest of the territory has a very low population density, which poses a challenge for the region’s ability to anchor itself in a territorial dynamic that is less dependent on the metropole’s (i.e., mainland France) resources. Finally, still specific to Sparsely Populated Regions, outside the municipality, the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region is also territorialized by the French state and by the various agents and mechanisms of territorialization that will be analyzed below, namely the Guiana Amazonian Park, the National Forestry Office, the Regulated Access Zone, and the Zones of Common Use Rights.

5.2. Incomplete State Territorial Control

Territorial management by mainland France remains theoretical insofar as the influence of the state on the various authorities in the territory—geographical, social, economic, and political [

47]—is incomplete. Given their low population density and their isolated character, Sparsely Populated Regions are difficult spaces to regulate and territorialize. This reality affects the state’s ability to exercise power, and thus guarantees the control of territorial resources through political and administrative regulations. The exercise of state power—ultimately expressed through coercion and law enforcement as a means of appropriating territorial resources to incorporate them into the larger economy [

48]—remains problematic. In this context, Sparsely Populated Regions become spaces that are conducive to illegal activities [

29].

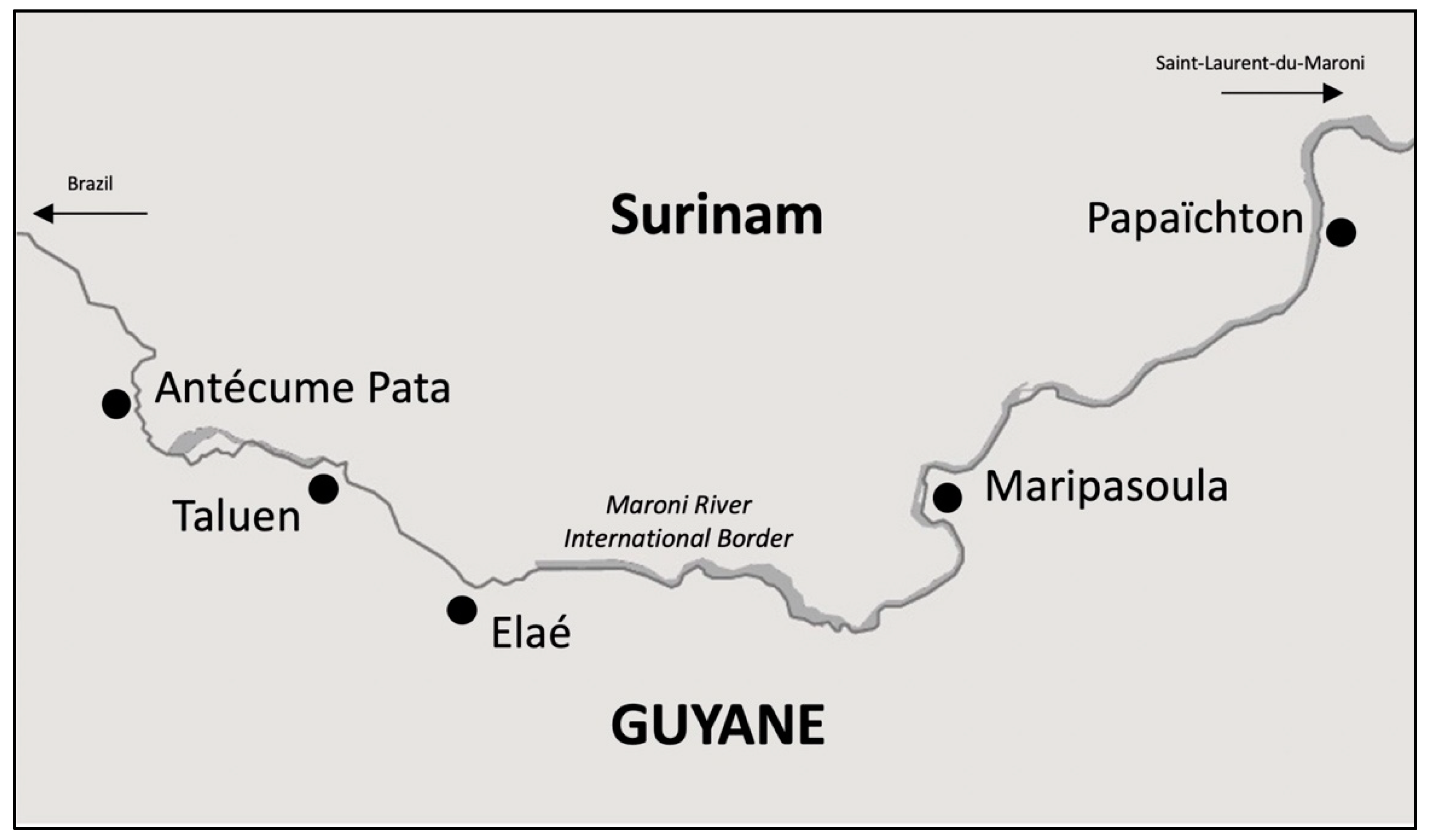

The characteristics of Incomplete State Territorial Control are clear in the greater Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region. The border between French Guiana and Surinam follows the Maroni River; there are very few border controls. This geopolitical and physical demarcation is an explicit demonstration that opposes the established territorial relations between formal territoriality—politically created and imposed—and functional territoriality, which is socio-culturally experienced [

47]. The living space of the populations that inhabit either side of the river is not conditioned by national borders, but rather by the daily activities that take place according to economic and socio-cultural needs. For example, opposite Maripasoula, in Surinam, there are a number of businesses, including grocery stores, bars, and Chinese-run hotels (

Figure 3). The products and services offered, sometimes illegal, are paid for in the various currencies circulating in the region—Euro, Brazilian Real, Surinam or American dollar—or even, according to our interviews, directly in gold since the region is heavily frequented by illegal miners. The border’s porosity, a result of the inability of the state to impose any formalization of the territory, contributes through the legitimate activities of daily life to creating gaps or spatial openings that encourage, among other things, illicit activities. The Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region is the scene of poaching, smuggling, illicit trade, and illegal gold panning, in addition to being a hub for illegal immigration [

49].

5.3. Distance from Axes of Mobility and Isolation

The remoteness of the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region can be quantified according to physical or temporal distance, whether in connection with the mother country, the capital, Cayenne, or neighboring regions in Brazil or Surinam. Although it is important to consider this quantitative approach, particularly when it comes to tourism, such an approach does not do justice to the notion of a Sparsely Populated Region. Indeed, the Distance from Axes of Mobility and Isolation criteria does not automatically apply to a region located far from axes of mobility. On this subject, Le Tourneau (2020) emphasizes that a qualitative approach is more appropriate for assessing the “remote” nature of this type of territory [

29]. It is important to be able to qualify the presence or absence of infrastructure or services, including roads, mobile communication networks, access to health care, the possibility of refueling, and the like. A Sparsely Populated Region, because of its isolation, confronts populations with challenges that affect all aspects of their daily lives.

These challenges take on their full meaning outside the town of Maripasoula. The only way to get to Haut-Maroni is by canoe. These trips are largely conditional on the river’s water level; even in optimal travel conditions, the 45 km journey between the villages of Taluen and Maripasoula takes a minimum of two hours by canoe. The town of Maripasoula is relatively well-equipped in terms of infrastructure and services, and is connected to the coast via a 24 h canoe trip to Saint-Laurent-Maroni or by a 55 min plane ride to Cayenne, the capital. The river is sometimes difficult to navigate and Air Guyane’s three daily flights are often fully-booked; thus, the capital remains difficult to access. In this context, services that are only available on the coast can be difficult to access and it is not uncommon to observe shortages in Maripasoula (food, medicine, and other commodities), particularly when inclement weather makes the journey arduous.

5.4. Presence of Societies with Distinct Lifestyles

The last inclusion criterion related to the concept of a Sparsely Populated Region focuses on the presence of societies with distinct lifestyles. This criterion refers to the presence of distinct peoples, so perceived from a colonial perspective, from which emerges the construction of Otherness, a Western essentialism is at the foundation of this ideological distinction [

50]. This Other, as described by Le Tourneau (2020), is not confined solely to ethnocultural differences, but is also defined by their distinct way of life [

29]. It evokes sociocultural relationships with the territory that testify to a strong attachment to the living space, involving conceptions of the world that is unique to each group occupying a given territory and which, therefore, help reinforce strong feelings of general territorial belonging. This can result in an exacerbation of conflicts with stakeholders who are exogenous to the territory with regards to the development or transformation of the living space.

The town of Maripasoula is host to a diverse ethnocultural mosaic and acts as a hub for the different ethno-cultural groups that make up the whole of French Guiana and its neighboring countries (

Table 2). In addition, the territory upstream of Maripasoula is occupied by the Indigenous Wayanas, who have their own socio-spatial organization of small villages that are often structured around the community carbet (hut), the “Tukusipan”. Our intention here is not to provide an ethnocultural description of the Wayana territory, but simply to underline the presence of a group with a distinct way of life. The question of subsistence activities, specific to the inhabitants of Haut-Maroni, is a central element to be considered when discussing the Zones of Common Use Rights, a mechanism for the territorialization of space set up by the French authorities.

6. Tourism in a Sparsely Populated Region

The Sparsely Populated Region inclusion criteria provide an overview of the particular territorial dynamics and consequent challenges that may arise from the practice of tourism. In addition to socio-cultural complexity, traveling in these regions can be time consuming and require significant financial resources. Inevitably, these two constraints affect tourist mobility. This section offers an analysis of the difficulties that travelers who decide to travel to the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region may encounter. Beyond the institutional and territorial complexities that influence the development of a tourist area, there are “practical conditions” that explain the weak development of tourism in this region.

Based on participatory observation and interviews carried out in 2019 with tourism stakeholders, we will describe the challenges of traveling to a territory that meets the Sparsely Populated Region inclusion criteria discussed above. Leaving from Cayenne, the intrepid traveler ventures to Taluen, on the Maroni, with a compulsory stop in Maripasoula. This “narrative” does not necessarily apply to all journeys in the region. We intend to highlight all the possible uncertainties that may be encountered to identify, from the point of view of the tourist, the specificities of tourism in such large spaces. Readers who have already traveled in French Guiana will be familiar with these wanderings, and anyone who has traveled in other Sparsely Populated Regions will find common elements.

The first inclusion criterion that characterizes mobility within the Sparsely Populated Region is, of course, the distance from the axes of mobility and isolation. There is no easy and user-friendly way to get to Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni. Upon arrival at Félix Éboué International Airport in Cayenne, the traveler has two options for travelling to Maripasoula, the departure point for canoes to Haut-Maroni. The first route starts in Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni (257 km and a 3 h drive from the airport), where travelers can negotiate a canoe booking with a freight carrier. Lucky travelers will be able to depart the next day or the day after. More affordable, this first solution is called “the hard way”. It is a bit like traveling by freighter rather than on a comfortable cruise ship. There is, however, an easier option. Travelers can find a tourist provider and pay more to go up the Maroni in relative comfort. Nevertheless, the Low Density inclusion criterion that influences territorial development, including the creation of a viable labor market, means that providers are in short supply, making the possibility of finding transport to Maripasoula uncertain. In both cases, it takes two to four days to reach one’s destination.

A flight is the second option. However, the Cayenne–Maripasoula route includes a stopover in Saül (

Figure 4). This small town of around 300 inhabitants, which also meets the Sparsely Populated Region criteria (except for the presence of societies with distinct lifestyles), is not connected to the road network and is only accessible by air. Since the plane is used both for transporting goods and passengers, priority is given to the needs of the community (Distance from Axes of Mobility and Isolation criterion—provisioning). In other words, tourists with tickets can board the plane. However, if perishable goods must go to Saül the same day, they will be placed in cargo. Tourists’ luggage will remain in Cayenne until there is a flight with more space.

Like canoe transport, air transport suffers from the effects of the Low Density inclusion criterion, meaning that there are only a few weekly connections on low-capacity aircraft (17 passengers). On weekends and during holidays (school or public holidays), the local population, accustomed to the low supply, books tickets several weeks in advance, making spontaneous travel difficult. The only airline to serve the territory, Air Guyane, operates at a loss and must rely on subsidies of up to 50% of each ticket sold (#1626) from the local French Guianese authorities to provide services (Low Density criterion—loss of service). An increase in services for tourism in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region would, in the current context, amount to subsidizing travelers.

Having arrived in Maripasoula, travelers will face new challenges, associated with a different Sparsely Populated Region inclusion criteria. First, they will quickly notice that tourist accommodation is limited; finding a room is not necessarily guaranteed. If no room is available, travelers can nevertheless fall back on accommodation in a carbet (Low Density criterion—deficient services), i.e., sleeping in a hammock in a semi-outdoor shelter (

Figure 5). In any case, during high season, it is important to book accommodation early; travelers will often have to find accommodation with locals due to a lack of space. Travelers will note with pleasure and relief that the town offers most basic services despite its isolation, including restaurants, snack bars, grocery stores, and the like. However, the services are still rudimentary and the top-of-the-range or “comfort” offer is absent. The visitor, therefore, quickly feels “far away” and isolated, a sensation that is exacerbated by the feeling of not being in a territory controlled by the state. Here, the situation of incomplete state territorial control can be observed in several respects, as will be discussed below.

Indeed, even if a number of institutional or semiotic clues remind travelers that they are in French territory, they are quickly confronted with the dynamics of visible socio-economic inequalities that are typical of economically marginalized countries. Maripasoula’s financial and material precariousness can cast doubt on the state’s ability to achieve territorial development that creates socio-economic opportunities for the entire population. In this regard, French Guiana is second to last among French administrative divisions on the Human Development Index [

51]. French Guiana has an index of 0.793, only ahead of the department of Mayotte (which has an index of 0.781) and is far behind Île-de-France (0.947). To better understand the center–periphery gap, French Guiana has approximately the same HDI as Trinidad and Tobago (0.796), while Île-de-France has an HDI closer to that of Germany (0.947). The average 1990-2019 HDI of Trinidad and Tobago/Germany was provided by the School of Applied Politics, University of Sherbrooke. This finding is not unrelated to the components of the Low Density criterion; in fact, the size of the development gap exacerbates the problems related to the state’s weak grip on the territory. We mentioned earlier some of the characteristics of incomplete state territorial control; these impact the tourist experience as well.

The element most directly associated with the inclusion criterion linked to Incomplete State Territorial Control relates to security. Admittedly, the feeling of security or insecurity can vary greatly from one person to another [

52,

53]. Beyond this individual perception, there is a real security problem in French Guiana. In fact, according to data from the French National Observatory of Delinquency and Criminal Responses (FNODCR), this territory is one of the least safe in France [

54]. Our goal here is not to provide a diagnosis of the state of criminality, but simply to highlight a situation that can undermine French Guiana’s attractiveness to tourists. When preparing for a trip, travelers may not necessarily carry out a risk analysis and carefully read the FNODCR data; instead, they may be influenced by the “image of the destination” that is constructed by the media [

55] and by other travelers’ testimonies (#1452). In fact, most tourists encountered in the field experienced insecurity qualms before going to French Guiana. That said, beyond a warning to avoid, rightly or wrongly, the Crique District in Cayenne, for example, tourists we spoke with had no reservations regarding the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region. Safety risks, if real, remain difficult for travelers to identify and name.

Illicit gold washers, smugglers, drug traffickers, and illegal immigrants are part of the “unsafe” setting described by the Incomplete State Territorial Control criteria [

29,

49,

56]. However, it is important to challenge the level of exposure to “risks” and determine whether they translate into real crime that is likely to affect the tourist experience in the region. Our interviews mainly focused on shipping service providers’ lack of training and the informal nature of accommodation as major risk factors, including shipments not declared to the prefecture, uninsured service providers, and employees who are not qualified for dealing with medical emergencies (#1625; #2055).

At the time of research, the French state had only partially undertaken measures to professionalize forest guides, and was not yet able to inventory the fleet of canoes in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region to register boats and train boatmen. This difficulty in applying standards and enforcing regulations with force demonstrate the presence of the Incomplete State Territorial Control inclusion criteria in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region (#2055). Attempts at regularization continue all the same, particularly through funding initiatives that are linked to obligations to respect state standards (#1821). In other words, when the imposition of the relational power of coercion and the use of strong-arm territorial control does not work, France tried to apply a form of softer territorial control through measures of structural power [

57], such as the financing of public services.

This finding, related to incomplete state territorial control, echoes another criterion for inclusion in the Sparsely Populated Regions, that of the Presence of Societies with Distinct Lifestyles. There is, particularly in the Haut-Maroni region, a feeling of the non-recognition of state borders that some segments of the population associate with a colonial project (#1600). As mentioned above, the functional territory, that is to say, territory associated with living space, transcends that of the formal territory associated with national boundaries. Imposing a formal territoriality on Indigenous nations stems from a misunderstanding of ways of life when the traditional living space does not fit within colonial territorial limits.

Without justifying the illegal activities that are associated with Incomplete State Territorial Control, we need to understand how they are perceived in the living space. Similarly, the imposition of a formalized living space by professionalizing the reception of visitors according to standards dictated by mainland authorities also exacerbates this feeling of the incomprehension of Indigenous ways of life. The government’s aim of regulating navigation on the Maroni and training guides faces certain resistance, insofar as the local population does not see the relevance of holding a license issued by the authorities since that they have an in-depth knowledge of the territory (#0918; #2055). Another element is added to this resistance when the training must be undertaken in French and outside of the guides’ own territory (#2055). These apparently postcolonial conditions represent a major obstacle for a certain segment of the population’s adherence to the state project in Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni.

To fully understand the effects of the aforementioned factors on tourism, we must reconnect with our hypothetical traveler as they continue their journey. The inclusion criterion linked to the Presence of Societies with Distinct Lifestyles is part of the sometimes-problematic relationship between host and visitor. Indeed, visitors to the Wayana territory face two elements that call into question the ethical relationship of tourism in the Haut-Maroni region. On the one hand, the region is part of a regulated access zone, which we will discuss later in terms of territorialization, and access is normally restricted. Anyone wishing to enter the Regulated Access Zone must mail in a request to the prefecture of French Guiana at least 15 days in advance [

58]. In other words, it is officially impossible to decide, once in Maripasoula, to go to this area right away. However, as we will see later, regulations linked to the Regulated Access Zone are not enforced (ISCT criterion) and the zone can be entered without authorization.

On the other hand, visitors must go through an operator to organize their stay because it is not possible to arrive in Wayana territory without an invitation (#1135). At the time of our visit, two operators offered excursions, although the possibility of staying in a village was not guaranteed. In addition, some communities interviewed in 2019 clearly indicated their desire not to receive visitors [

46]. When travelers do manage to reach a community, they must make sure to respect the social and cultural norms in force. In this regard, due to unfortunate incidents when visitors behaved inappropriately, the Guiana Amazonian Park has developed a guide to good conduct [

58] for travelers to try to avoid irresponsible behavior during their stay (

Figure 6).

This story of the challenges and socio-territorial dynamics that await travelers hoping to go to Haut-Maroni does not pretend to cover all the difficulties that are related to travel in this region or in French Guiana as a whole. Nor is it intended to discourage anyone from traveling to this sparsely populated region. The exercise aims to highlight the territorial dynamics that emerge from the practice of tourism in a Sparsely Populated Region, in order to show that such territory does not lend itself to improvisation and/or a cavalier attitude when traveling there. Sparsely Populated Regions are not easily accessible, and any attempt at access is part of a dynamic of commitments far beyond the carefree nature of conventional tourism. The Sparsely Populated Region inclusion criteria apply to the Maripasoula and Haut-Maroni regions, a fact which, in itself, constitutes a very important barrier to tourism development. Despite these major constraints, there is still a real desire to develop the tourism sector in the region, particularly on the part of the Guiana Amazonian Park [

46].

7. Production of a Tourism Space: Agents and Mechanisms of Territorialization

The rest of our analysis proposes to approach the tourism question not from the angle of the tourist, but rather by considering the tourism sector. More specifically, after declaring an intention to develop tourism in a territory, how are the different territorialization agents and mechanisms mobilized to produce a tourism space in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region?

Beyond different stakeholders’ strategies, actions must be taken to create a space that is conducive to the territorial deployment of tourist activities. A priori, given its explicit interest in tourism development, the Guiana Amazonian Park is identified as the main agent likely to contribute to the production of this space in the Maripasoula/Haut Maroni region. For example, through the Park Charter, which territorializes communities’ spatial life, the Guiana Amazonian Park identifies the institutional actions that are necessary in order to establish tourist activities. Interviews helped us identify the agents and mechanisms of territorialization to better understand how the latter contribute to the territorial dynamics linked to tourism. Our interviews were based on a questionnaire that considered a set of criteria that delineated the factors necessary in order to achieve a process of participatory co-management between the stakeholders involved in territorial development [

59]. Most studies on co-management focus on the institutions themselves or on community-based approaches, but few explore the intersection of these two things [

1,

60,

61]. Exploring this intersection is particularly relevant in the case of the PAG since the State initiated the project, but it has gradually adopted local communities’ participatory and consultative approach. This includes the following objectives: to grant particular importance to stakeholders’ different needs and the arrangements that will allow benefits to be distributed among these stakeholders; the construction of social norms; the formation of vertical and horizontal links to consolidate trust and social learning; and the diversity of types of knowledge taken into account.

The principles underlying adaptive co-management serve in particular to identify the extent to which learning and institutional and bureaucratic adaptation take place, since adaptive co-management requires collaboration and the establishment of links between social actors both at the horizontal and vertical levels [

59] (p. 98): “Careful analysis of institutional processes, structures, and incentives is vital, since the interactions of the various stakeholders are unlikely to be socially or politically neutral”. In theory, the PAG Charter was developed according to general principles, consistent with adaptive co-management. In particular, it plans to perform the following: “(1) Produce and share knowledge in the service of territorial issues based on research and the knowledge of local communities. (2) Build effective governance for the territory in which local governance and the French administrative and political system meet. (3) Adapt public policies and regulations to the realities of the territories. (4) Develop cooperation with protected areas and countries in the Americas zone. (5) Integrate the territories that form part of the Guyana Amazonian Park into the regional whole” [

62] (p. 39–48).

The criteria used in this research were inspired by adaptative co-management principles and were attached to a set of standard questions that guided our semi-structured interviews.

Table 3 presents the criteria and questions the stakeholders identified as important issues in terms of territorial management related to tourism development in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region. For each of the criteria, analyzing the interviews revealed which territorialization agents and mechanisms were perceived as most structuring in the dynamics of the touristification of the region.

The National Forestry Office (NFO) and the Guiana Amazonian Park (GAP) are identified in 7 of the 10 criteria. The Zones of Common Use Rights (ZCUR) and the Regulated Access Zone (RAZ) are associated with 6 and 5 of the criteria, respectively. Other territorialization agents and mechanisms, such as the prefecture, the local council, the local life committee, and the French army, as well as territorial management tools such as the community of communes, were mentioned on a few occasions, but mainly as peripheral actors.

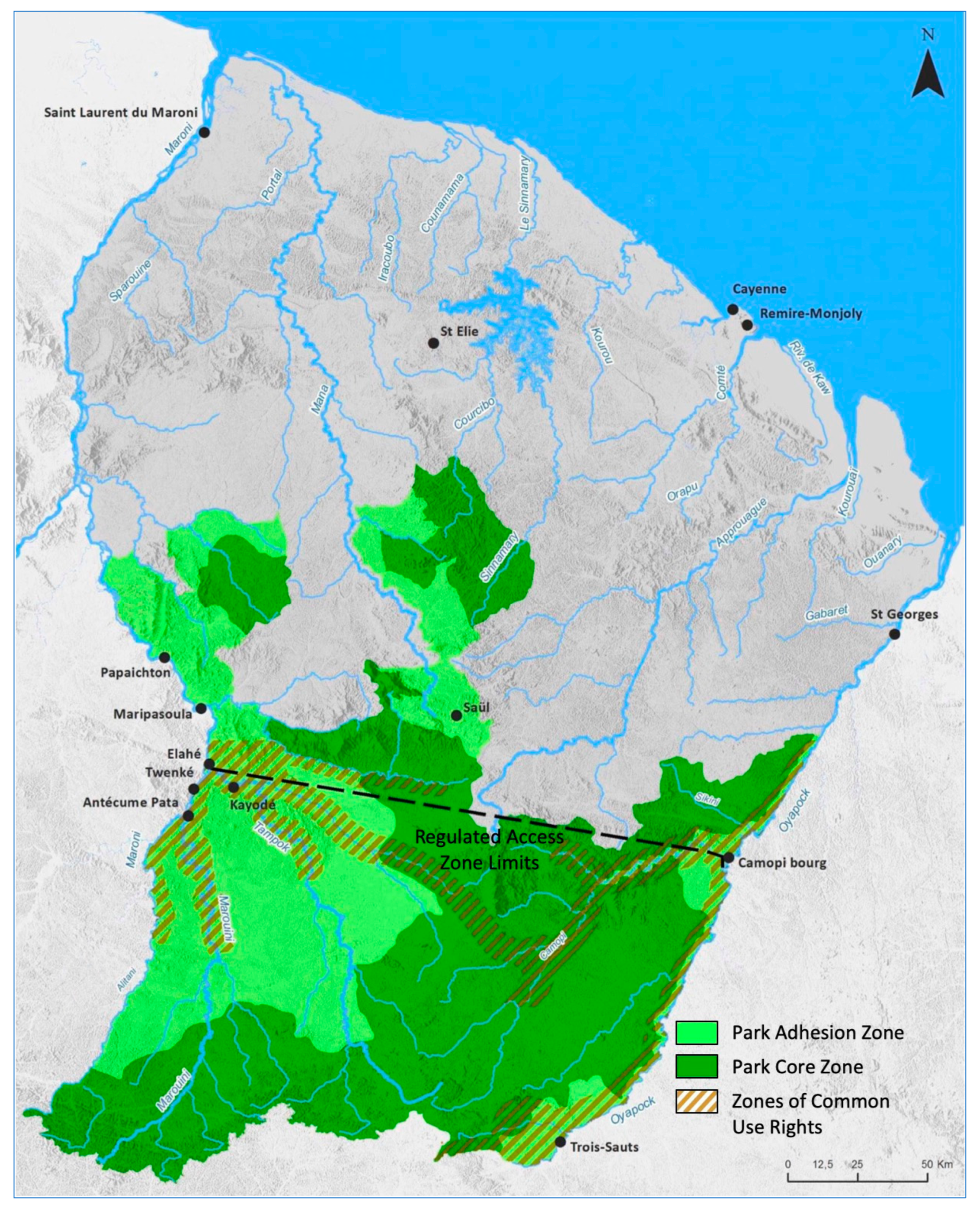

These added layers of territorialization [

47] have implications for the deployment of tourism in the region (Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni). First, there is the National Forestry Office, a government institution whose importance is crucial to the territorial management of forests throughout French Guiana. The National Forestry Office was mentioned in all of the interviews concerning tourism and soon emerged as a leading territorialization agent. Stakeholders questioned two territorialization mechanisms: the Regulated Access Zone and the Zones of Common Use Rights. Other territorial agents and mechanisms have more of an indirect effect on the production of a tourist space (e.g., the community municipality, the French Guiana Tourist Office). For the purposes of our analysis, we will focus on the quartet of the Guiana Amazonian Park, National Forestry Office, Zones of Common Use Rights, and, to a lesser extent, Regulated Access Zone, because of the importance given to them during our interviews.

This discussion does not aim to review all the technical details relating to the elements that these agents and mechanisms impose in terms of territorial governance. However, it is important to understand that the territorial management of the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region reflects four levels of the territorialization of the living space (

Figure 7), spawning governance regimes that must be taken into account when deciphering the creation of a tourist area. Indeed, tourism stakeholders must navigate all the parameters of territorial management that are generated and activated simultaneously by these regimes in order to create a space in which tourism can fully develop. We do not claim to grasp the vast array of administrative entanglements and technopolitical dynamics these governance regimes create. Rather, we seek to highlight the complexity of territorialization processes and the challenges they represent, so as to foreground how the development of tourist practices, above and beyond the challenges of a Sparsely Populated Region, are part of territorial management and how they may help or hinder the deployment of this economic activity.

Created in 2007, the Guiana Amazonian Park extends over 3.4 million hectares, or 40% of French Guiana. It includes a core area of 2 million hectares, which is protected by specific regulations aimed at preserving its natural landscape and cultural heritage. The rest of the park is made up of an adhesion zone that includes the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni area. This is where the Guiana Amazonian Park implements context-specific support measures for local development to meet the requirements of the Guiana Amazonian Park Charter. While the park’s core zone is essentially dedicated to the creation of discovery trails, not entailing permanent construction, the adhesion zone is the subject of more diversified orientations, including the promotion of sustainable tourism (ecotourism and enhancing knowledge of the tourism sector). Finally, as stated in the charter, the Guiana Amazonian Park only acts as a facilitator through its role as a technical and financial partner for the park’s general development [

63].

It should be noted, however, that the only domain entirely managed by the Guiana Amazonian Park is the core zone. The adhesion zone is managed by the National Forestry Office, which administers 6 million hectares of forest, including 1.4 million hectares in the Guiana Amazonian Park adhesion zone. This means that more than half of the core zone protected area falls under the jurisdiction of the National Forestry Office, which applies its regulations and implements its own vision of ecotourism development. In particular, through its environmental and tourism studies office, the Office administrates the development of forest trails, as well as access roads and related immovable property (fences, benches, carbet huts, signage, and the like). Management procedures reflect a desire for economic development through a timber production program.

Created in 1987, Zones of Common Use Rights are areas made available to “communities of inhabitants who traditionally draw their livelihood from the forest” and that mediate several aspects of beneficiary communities’ living space [

12]. Davy and Filoche (2014) identified five categories of land system impact: cultural identity, housing, agriculture, the use of natural resources, and economic activities [

64]. For the time being, tourism applies strictly to guests’ reception area, i.e., no accommodation infrastructure is allowed due to the regulations that underpin the zone’s subsistence function. A blurring of legal interpretation clouds the entire Zones of Common Use Rights concept, creating significant confusion among tourism stakeholders and hampering the development of the sector (#1405; #2055). Indeed, it is difficult to define subsistence, which can be seen restrictively as devoted to survival or, more broadly, to allow for adaptation linked to local populations’ current reality (demographic increase, economic development, and the like). The government applies a restrictive understanding of subsistence, while Zones of Common Use Rights beneficiaries call for the lifting of certain restrictions to be able to benefit from the territory (#1022).

Finally, the Regulated Access Zone represents a territorial control tool put in place in 1970 to protect the local Indigenous population from the health risks caused by the presence of foreigners in the territory [

65]. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, this zoning was contested by part of the local population and discussions were underway to redefine its future (#1405). In fact, as we have already explained, if enforced by authorities, Regulated Access Zone regulatory mechanisms can impede mobility. It is important to note that the area was little monitored before 2020, a situation that has changed due to the health risks linked to the pandemic [

7].

8. The Territorial Entanglement of Agents and Mechanisms of Territorialization

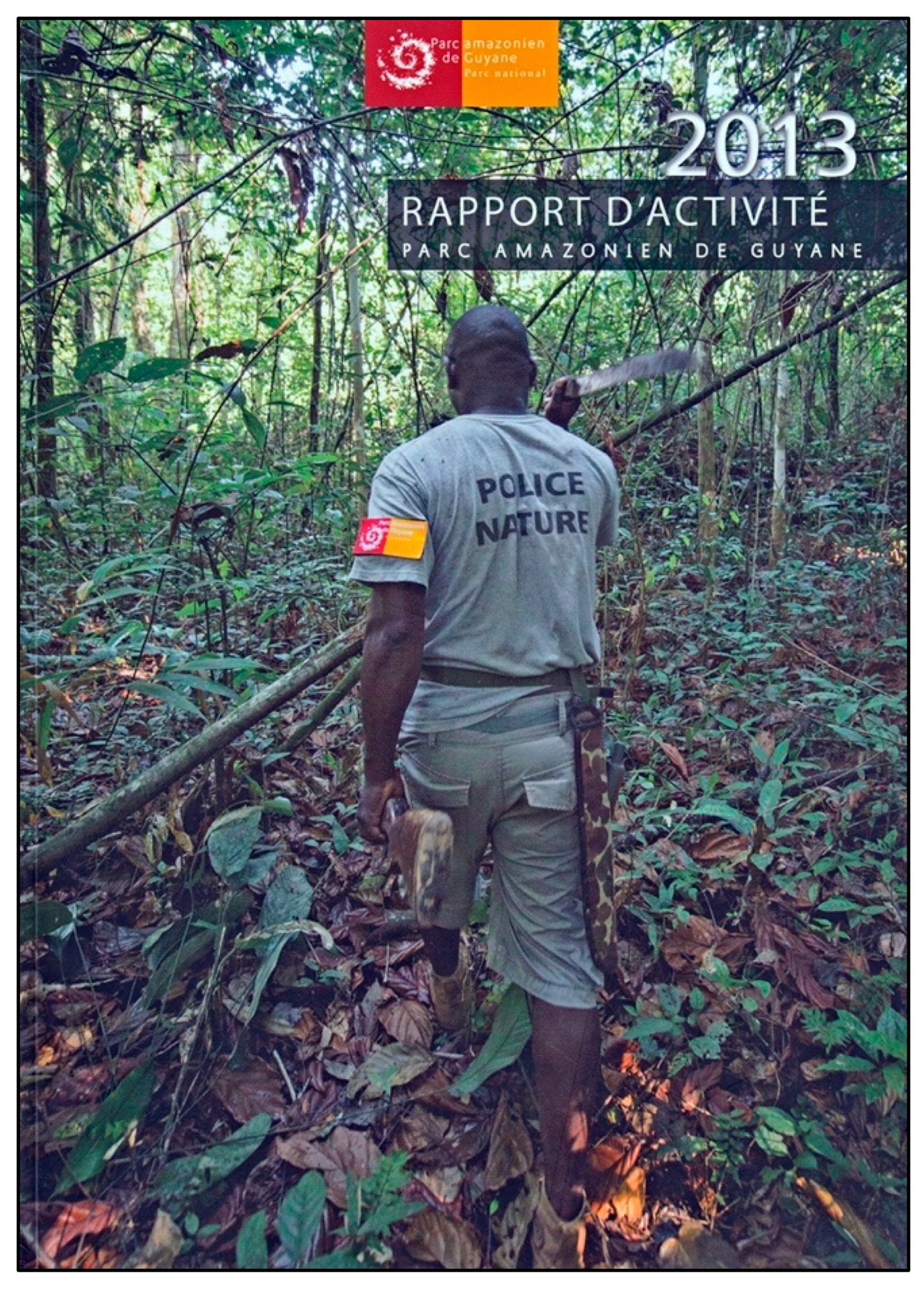

While the Guiana Amazonian Park shows a desire to develop the tourism sector, its management model and territorial subordination in the adhesion zone vis-à-vis the National Forestry Office considerably reduce its ability to territorialize the living space of communities that have adhered to the Charter. One of the notable territorial effects of Guiana Amazonian Park presence, in the Saül region and, to a lesser extent, in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region, is its role in the fight against illegal gold panning (#1026; #1642). Park agents and tourists in the various developed areas of the park act as a watchdog over the Garimpeiro, the clandestine gold diggers in French territory. In addition, during the Guiana Amazonian Park’s first years of operation, agents exercised a significant coercive role, enforcing regulations concerning the exploitation of territorial resources, mainly related to illegal hunting and fishing (

Figure 8). This situation led communities adhering to the Charter to protest. Since then, the Guiana Amazonian Park has reoriented its actions towards awareness-raising and environmental education measures, leaving the coercive aspect of the management of the territory to the National Forestry Office (#1821).

From the tourist’s point of view, the role of the Guiana Amazonian Park is simple. It is part of a network of actors striving to contribute to the development of a tourism vocation in the region. In other words, it acts as a development tool by establishing a dialogue between stakeholders to determine what is or is not desirable (#1821). The Guiana Amazonian Park’s support role is part of a mission to improve the living environment and, in this respect, it participates in the modification of certain areas of the living space by setting up infrastructure. Otherwise, the PAG role as a community partner is expressed in terms of communication and territorial education actions (valorisation of nature, environmental awareness, and the like).

Finally, the park also offers support as a facilitator in the context of funding actions for the tourism sector. This is part of the LEADER program, one of the components of the European fund for development and the rural economy. In fact, the park, as a territorial governance structure, receives a certain budget to use to set up a technical unit to support its financial objectives. This is a type of governance that is based on public–private partnerships (PPP), including elected officials, communities, socio-professionals, and associations that together make decisions concerning the allocation of aid. Thus, the Guiana Amazonian Park indirectly occupies the living space through its territorial actions and occupies the economic space by seeking to contribute to Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni’s development. It is clear that improved economic health for the region would make it easier to promote the Guiana Amazonian Park’s initiatives to combat gold panning and to respond to the various challenges related to preserving the Park’s natural spaces (#1821).

To better grasp how the Guiana Amazonian Park becomes an indirect producer of tourist space, it is also important to understand the territorialization power of the National Forestry Office through its state management of forests and natural resources. The Guiana Amazonian Park’s adhesion zone is part of the “undetermined vocation forest”. From the National Forestry Office’s point of view, it is a preservation zone in which any action must ultimately refer back to its territorial management decision-making mechanisms. Concretely, project promoters (the Guiana Amazonian Park and the local partners they support) must “contract” with the National Forestry Office. For tourist activities, this involves defining the area in which these activities can take place and verifying that these meet the guidelines already in place: authorized infrastructure, environmental protection, the prohibition of hunting and fishing, the prohibition of logging, waste management, and so forth. Once established, the administrative contract is valid for a renewable period of 6 to 9 years, with the ultimate objective being to prevent the territory from being privatized. The idea is to compensate for the lack of a local vision regarding land use planning (#1217), thus avoiding the production of poorly planned enclaves in areas of tourist potential that the National Forestry Office hopes to highlight.

The National Forestry Office’s ability to territorialize is part of the unequal center/periphery power dynamic that is characteristic of socio-territorial relations between Sparsely Populated Regions and central power [

26]. In this regard, the National Forestry Office is a central metropolitan body in the French state’s governance system in Guiana that acts in the Sparsely Populated Region, its periphery. Local populations’ decision-making power related to the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni living space remains weak (#1642), and the state is reluctant to concede any form of territorial management, citing various pretexts linked to local authorities’ chronic inability to take charge of their territory (#1642; #1716). This type of relationship is based on historical and colonial mechanisms that are not analyzed here, but which appear implicitly in the territorial management processes the French state grants to local communities within the framework of the Zones of Common Use Rights. These are the only areas beyond the National Forestry Office’s direct management, but the challenges linked to establishing tourism in these areas reveal the lack of sovereignty that the various local groups (Indigenous in the upper Maroni) exercise on their territory.

A Zone of Common Use Rights is a tool for the state recognition of communities’ territorial claims, but it recognizes the specificity of Indigenous peoples only through a restrictive vision of the notion of subsistence. In fact, Zones of Common Use Rights exercise usufructuary rights on the land, which remains the property of the state according to the principle of land without an owner. This governance context has impacts, particularly on the issue of relations with the National Forestry Office. Indeed, these areas are granted to a community of inhabitants within a framework in which there is no explicit manager. In other words, in the absence of an established manager, when questions related to resource management arise and go beyond the rather vague framework of the notion of subsistence, it is up to the state to assert its prerogatives.

According to the French state, resources must not be exploited for commercial purposes, even if this prohibition is only partially defined (#1642). Thus, local stakeholders continually find themselves at an impasse in the development of natural resources. For example, in the Zones of Common Use Rights, wood may be removed for domestic purposes, but selling wood is illegal. It is also difficult to determine whether an individual has the right to let a carbet originally built for family members to tourists; in this case, the question of marketing comes into play. In the same vein, selling forest resources in the form of handicrafts is legal, but the National Forestry Office requires that the locals pay for the resources extracted from the area, thus keeping the development of this type of activity under outside control, a situation that generates significant tensions (#1226).

Another obstacle relates to the question of financing. Zones of Common Use Rights projects that could be tolerated, including, for example, low-impact reception facilities, come up against the established land tenure system. In fact, the LEADER program requires solvency in terms of the land that Zones of Common Use Rights users cannot provide because they do not own the territory. In this context, a community member might want to build a hut for tourists, an undertaking that neither the National Forestry Office nor the Guiana Amazonian Park can limit in practice (#1621; #1217), but it would be impossible to have access to a loan to buy tools. Thus, the obstacles to tourism development are mainly financial because, insofar as tourist facilities remain modest, tourism practices in the Zones of Common Use Rights are usually tolerated. The challenge then remains two-fold: to expand the notion of subsistence and to acknowledge the issues related to territorial sovereignty. Moreover, what is true for tourism is also true for other sectors of economic activity.

9. Conclusions

Tourism is experienced today as more than a simple economic activity; it is a transformative force that acts simultaneously on populations and destinations by shaping their representations. The critical perspective that underlies our approach to deconstructing the processes of exercising power does not oppose tourism or directly reject its positive manifestations; it does, however, seek to understand how the exercise of power [

66] influences processes of territorialization [

47], generating spaces of resistance for local populations in the face of the normalizing and homogenizing forces of tourism [

67]. Our approach is in line with that of Hollinshead et al. (2009), as expressed through the concept of “Worldmaking” [

68]. Worldmaking suggests that through groups of actors’ exercise of power, we witness the hegemonic imposition, whether conscious or unconscious, of an ideological, narrative framework of domination. This contributes to the production of a tourist space that deprives host populations of the capacity to take charge of their own territory. In this process of exclusion, Worldmaking not only marginalizes local stakeholder groups, but also expands geographically due to the increased ubiquity of tourism in living spaces [

69,

70,

71].

Worldmaking also echoes issues related to the commodification of nature under a neoliberal economic regime in the context of tourism development in a protected area [

8]. Under the aegis of ecotourism activity, tourism development in the Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni region is part of a shift that can reallocate a natural preservation space away from sociocultural utilities, and integrate it into the market to thus feed capitalist development. The real risk is that tourist exploitation of the Guiana Amazonian Park’s natural resources allows the State, notably through the National Forestry Office and the conservation policies of the French state, to create power structures that ultimately allow private tourist companies to insert themselves into territorial management and influence the establishment of conservation rules to the detriment of local actors. The latter, already lacking territorial power, are unable to participate fully in territorial management when faced with the agents and mechanisms of current territorialization. In the end, even if the Guiana Amazonian Park is not considered a primary territorialization actor, its role as a facilitator for tourism development means that it opens the door for the commodification of nature. Given the nature of the National Forestry Office’s mission, and that it already operates commercial development projects, it is the latter, through its power of territorialization, that will become the commodification vector of the Guiana Amazonian Park adhesion zone.

The way we conceive of the production of spaces has the advantage of favoring an understanding of the restructuring of community living spaces as new economic activities, such as tourism, are established. It is therefore possible to better understand how a combination of political action, economic context, and socio-cultural perceptions serve to redefine territories, clarifying issues linked to power relations that appear when the territoriality of spaces with distinct uses—living spaces and protected areas—is renegotiated through tourist development. The production of tourist spaces discussed here is also part of particular dynamic-specific constraints that are linked to Sparsely Populated Regions, and the different governance regimes analyzed as part of this case study. On the one hand, we outlined the challenges of developing tourism linked to a Sparsely Populated Region according to the different criteria that define this concept. On the other hand, we discussed the core/periphery governance issues related to a Sparsely Populated Region that affect tourism. These are based on territorialization agents and mechanisms inherited from the colonial regime, the nature of which favors the production of tourist areas of a “Worldmade” nature.

Our view of the Maripasoula/Haut Maroni region through the lens of social and political geography can only be a first step toward an in-depth reflection on the socio-territorial issues that underlie the development of tourism in the region. The production of a tourism space in a Sparsely Populated Region conceals issues that go well beyond tourism itself and affect all the socio-spatial bodies that make this living space a reality [

47]. Indeed, the regional economy, concrete territory, cultural elements, and political dynamics come together to produce a territory that is subject to a colonial regime that does not recognize the sovereignty of the peoples living there. This absence of self-determination runs counter to the notion of territorial responsibility upstream of any type of emancipation, a concept more important than development, with the first necessarily preceding the second.

Our analysis contributes to the emergence of new questions: does the territorialization induced by the touristic development of natural resources create new territorial exclusions? Is nature tourism only a transitional stage that facilitates the passage of local populations (notably through the development of infrastructure, making these territories more accessible and facilitating the development of market relations) to new modes of subsistence more intensely linked to the market economy? This is what livelihood studies seem to propose. As for the conservation of biodiversity, environmental balances and the sustainability of systems, how can they be reconciled with new emerging territorial dynamics and the aspirations of local populations? The coming decade will provide the answer, but the outlook in this area seems bleak.

In a postcolonial context, it remains difficult for the inhabitants of Haut-Maroni to negotiate their condition as equals. Although the Guiana Amazonian Park shows a certain sensitivity to “bottom-up” approaches, it is the very structure of the political regime that needs to be reviewed. Analysis of the tourism “object” exposes only part of the territorial dynamics to be examined. Tourism, along with any other form of activity to be developed in Maripasoula/Haut-Maroni territory, will be systematically confronted with the same structural constraints that have helped to reproduce the dynamics of territorial dispossession since the establishment of a colonial regime in the region. The recognition of rights and the establishment of a form of Indigenous self-government are the only avenues to promote authentic sustainable development for the benefit of local populations and in the spirit of redistributive social justice [

72]