Why Travel to Georgia? Motivations, Experiences, and Country’s Image Perceptions of Wine Tourists

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Georgia as a Wine Country and Developments of Tourism and Wine Tourism

1.2. Country Image and Its Interaction with Wine Tourism

1.3. Purpose of the Study

2. Literature Framework

2.1. Country Image

2.2. The Motivation of the Wine Tourists

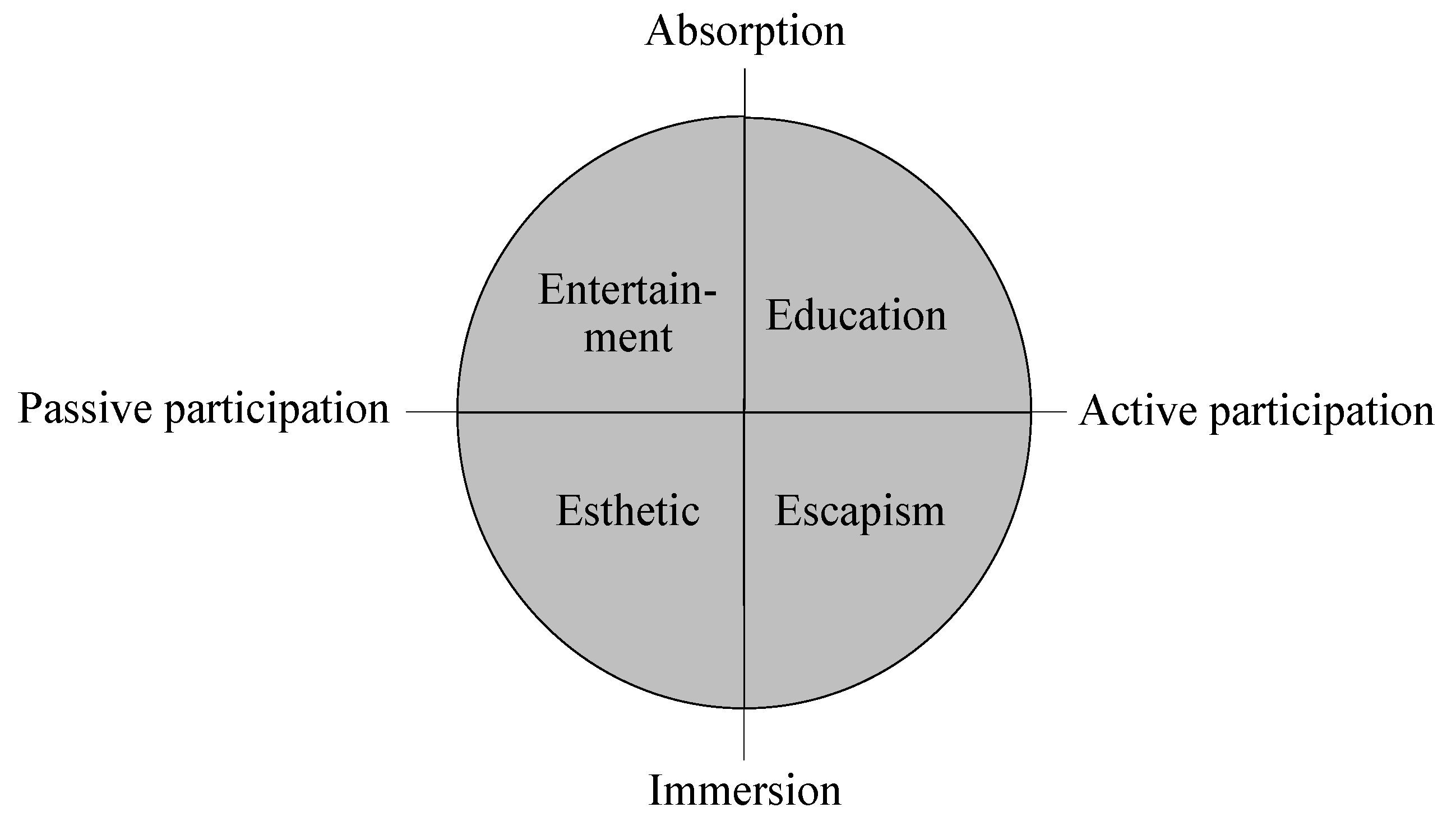

2.3. Expectations of the Experiences of Wine Tourists Using the Experience Economy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures and Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Sample Description

4.2. Perceived Country Image of Georgia

4.3. Motivation to Visit Georgia

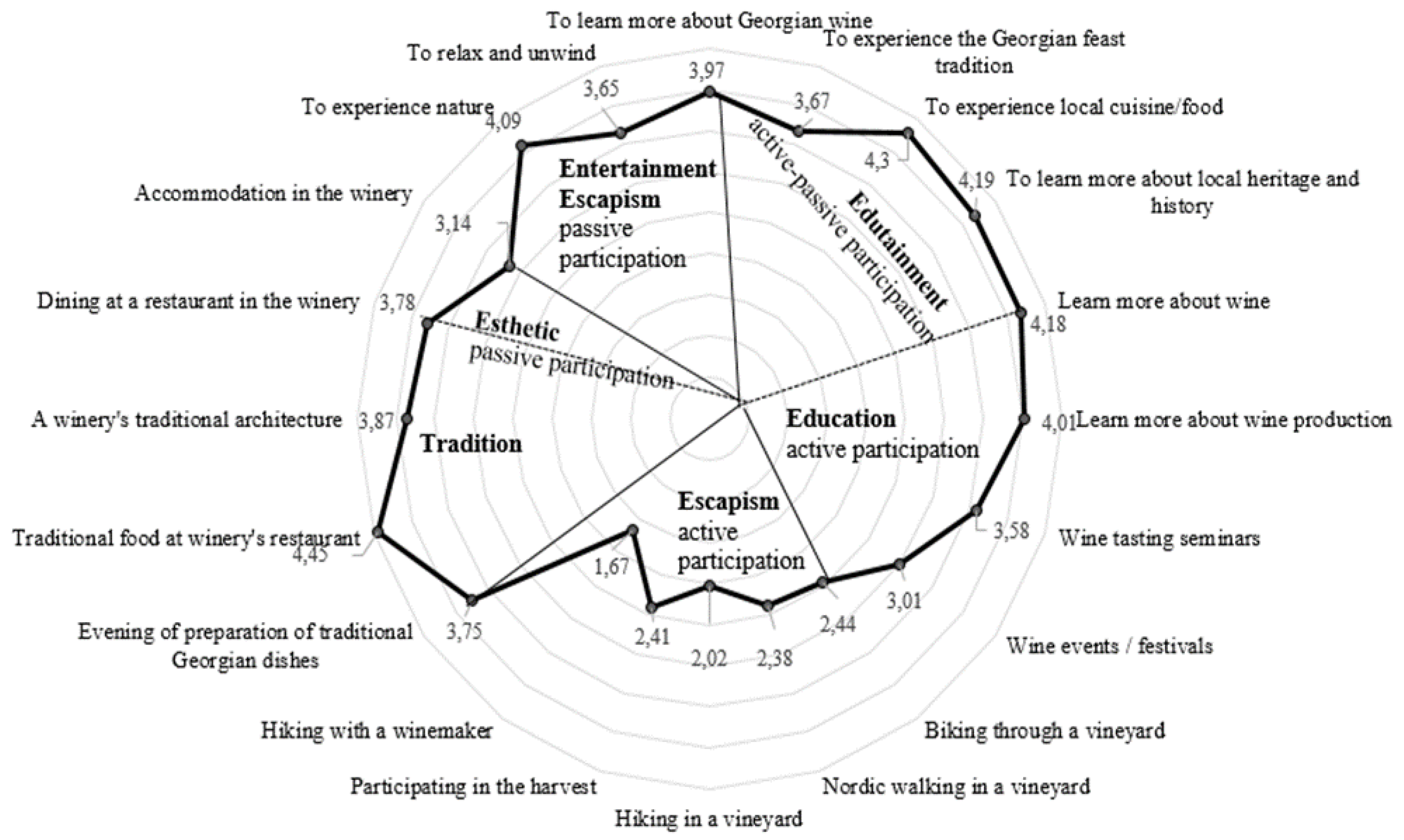

4.4. Expectations of the Experiences of Wine-Related Activities and Wineries in Georgia

5. Conclusions, Implications, Limitations, and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations

5.4. Recommendations for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Velikova, N.; Bouzdine-Chameeva, T. Georgian Wine Museum Is Making a Strategic Decision. In Wine Tourism Destination Management and Marketing; Sigala, M., Robinson, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghvanidze, S.; Bitsch, L.; Hanf, J.H.; Svanidze, M. The Cradle of Wine Civilization—Current Developments in the Wine Industry of the Caucasus. Cauc. Anal. Dig. 2020, 117, 9–15. Available online: https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/CAD117.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Granik, L. Understanding the Georgian Wine Boom. SevenFiftyDaily 2019. Available online: https://daily.sevenfifty.com/understanding-the-georgian-wine-boom/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Georgian National Tourism Administration. Georgian Tourism in Figures. Available online: https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ENG-2016.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- National Statistics Office of Georgia (Geostat). Inbound Tourism Statistics in Georgia 2019. Available online: www.geostat.ge (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Worldbank.org. GDP-Georgia. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2021&locations=GE&start=2017 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Khartishvili, L.; Muhar, A.; Dax, T.; Khelashvili, I. Rural Tourism in Georgia in Transition: Challenges for Regional Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 410. Available online: www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/2/410 (accessed on 20 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Wirtschaftsvereinigung Georgien (DWVG). Georgien Kompakt Wein 2010. Available online: http://dwvg.ge/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/georgienkompakt-Wein.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- OIV Statistics. Online Database. Available online: www.oiv.int/de/datenbank-und-statistiken-vornehmen/statistiken (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Bruwer, J.; Pratt, M.A.; Saliba, A.; Hirche, M. Regional destination image perception of tourists within a winescape context. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Mitchell, R. Wine and food tourism. Special Interest Tourism: Context and Cases; Wiley: Brisbane, Australia, 2001; pp. 307–329. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, U.; Wolf, M.; Dodd, T. Dimensions of wine region equity and their impact on consumer preferences. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N.; Heslop, L. Country equity and country branding: Problems and prospects. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Bruwer, J. Regional brand image and perceived wine quality: The consumer perspective. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2007, 19, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remaud, H.; Lockshin, L. Building brand salience for commodity-based wine regions. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ittersum, K.; Candel, M.; Meulenberg, M. The influence of the image of a product’s region of origin on product evaluation. J. Bus. Res 2003, 56, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Lesschaeve, I. Wine tourists’ destination region brand image perception and antecedents: Conceptualisation of a winescape framework. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Ali-Knight, J. Who is the wine tourist? Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Prayag, G.; Disegna, M. Why wine tourists visit cellar doors: Segmenting motivation and destination image. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Alant, K. The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Johnson, G.; Cambourne, B.; Macionis, N.; Mitchell, R.; Sharples, L. Wine Tourism Around the World–Development, Management, and Markets; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Alebaki, M.; Iakovidou, O. Market segmentation in wine tourism: A comparison of approaches. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2011, 6, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. The relationship between the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors of a tourist destination: The role of nationality—An analytical qualitative research approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Fountain, J.; Fish, N. “You felt like lingering...” Experiencing “real” service at the winery tasting room. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Ramos, P.; Almeida, N.; Santos-Pavón, E. Developing a wine experience scale: A new strategy to measure holistic behaviour of wine tourists. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, R.; Brito, C. Wine tourism and regional development. In Wine and Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, V.R.; Ramos, P.; Almeida, N.; Santos-Pavón, E. Wine and wine tourism experience: A theoretical and conceptual review. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Gross, M.J.; Lee, H.C. Tourism destination image (TDI) perception within a regional winescape context. Tour. Anal. 2016, 21, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Rueger-Muck, E. Wine tourism and hedonic experience: A motivation-based experiential view. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitow, D. Produktherkunft und Preis als Einflussfaktoren auf die Kaufentscheidung—Eine Experimentelle und Einstellungstheoretisch Basierte Untersuchung des Konsumentenverhaltens bei Regionalen Lebensmitteln. Ph.D. Thesis, Landwirtschaftlich-Gärtnerische Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, J.; Gilmore, J. The Experience Economy–Work Is Theater and Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rüdiger, J.; Hanf, J.H.; Schweickert, E. Wine Tourism and Associated Expectancies of German Consumers = Weintourismus und damit einhergehenden Erwartungshaltungen in Deutschland. In 38th World Congress of Vine and Wine; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2015; Volume 93, Issue 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, J.L.; Mas, F.J. The influence of distance and prices on the choice of tourist destinations: The moderating role of motivations. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 982–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Getz, D. Linking wine preference to the choice of wine tourism destination. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Johnson, R. Place-based marketing and regional branding strategy perspectives in the California wine industry. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermiller, C.; Spangenberg, E. Exploring the effects of country of origin labels: An information processing framework. Adv. Consum. Res. 1998, 66, 454–459. [Google Scholar]

- Balabinas, G.; Mueller, R.; Melewar, T. The human values’ lenses of country of origin images. Int. Mark. Rev. 2002, 19, 582–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Romeo, J. Matching product category and country image perceptions: A framework of managing country-of-origin effects. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1992, 23, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N. What product and country images are and are not. In Product Country Images: Impact and Role in International Marketing; International Business Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ghvanidze, S. Bedeutung des Country-of-Origin-Effekts für die Wahrnehmung deutscher Weinkonsumenten: Eine Untersuchung am Beispiel des georgischen Weines; Dissertaion. Cuvillier: Gottingen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, S. Der Herkunftslandeffekt für Sektgrundweine: Eine empirische Untersuchung unter Verwendung Kompositioneller und Dekompositioneller Methoden; TUDpress Verlag der Wissenschaften: Dresden, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Profeta, A. Der Einfluss geschützter Herkunftsangaben auf das Konsumentenverhalten bei Lebensmitteln. Eine Discrete-Choice-Analyse am Beispiel Bier und Rindfleisch; Studien zum Konsumentenverhalten, Bd. 7; Verlag Dr. Kovač: Hamburg, Berlin, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, T. Landesimage und Kaufentscheidung, Erklärung, Messung, Marketingimplikationen; Deutscher Universitätsverlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, J.; Dreyer, A. Weintourismus: Märkte, Marketing, Destinationsmanagement-mit Zahlreichen Internationalen Analysen; ITD-Verlag: Hamburg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.; Hall, C.M.; McIntosh, A. Wine tourism and consumer behavior. In Wine Tourism Around the World–Development, Management and Markets; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hillmann, K.H. Handbuch der Soziologie; 4. überarbeitete Auflage; Alfred Kröner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Luft, H. Grundlegende Tourismuslehre; Gmeiner-Verlag GmbH: Meßkirch, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hosany, S.; Zeglat, D.; Odeh, K. Measuring experience economy concepts in tourism: A replication and extension. Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally. 2016, p. 28. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1505&context=ttra (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Baron, S.; Conway, T.; Warnaby, G. Relationship marketing: A change in perspective. In Relationship Marketing: A Consumer Experience Approach; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M.J.; Reynolds, K.E. Hedonic shopping motivations. J. Retail. 2003, 79, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.R.; Stöckl, A.; Brouard, J.; Cavicchi, A.; Faraoni, M.; Larreina, M.; Lecat, B.; Olsen, J.; Rodriguez-Santos, C.; Santini, C.; et al. Having a great vacation and blaming the wines: An attribution theory perspective on consumer attachments to regional brands. In Developments in Marketing Science: Proceeding of the 2010 Academy of Marketing Science, 1st ed.; Deeter-Schmelz, D.R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Granik, L. The Wine of Georgia; Infinite Ideas: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Knekta, E.; Runyon, C.; Eddy, S. One Size Doesn’t Fit All: Using Factor Analysis to Gather Validity Evidence When Using Surveys in Your Research. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2019, 18, rm1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Li, E.; Bastian, S.; Alant, K. Consumer household role structures and other influencing factors on wine-buying and consumption. Aust. N. Z. Grapegrow. Winemak. 2005, 503, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Famularo, B.; Bruwer, J.; Li, E. Region of origin as choice factor: Wine knowledge and wine tourism involvement influence. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2010, 22, 362–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistics Office of Georgia (Geostat). General Population Census; Geostat: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alant, K.; Bruwer, J. Wine tourism behaviour in the context of a motivational framework for wine regions and cellar doors. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, P.R.; Browlow, C.; McMurray, I.; Cozens, B. SPSS Explained; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, J.D.; Tanis Ozcelik, A. Preservice teachers developing coherent inquiry investigations in elementary astronomy. Sci. Educ. 2015, 99, 932–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretz, S.L.; McClary, L. Students’ understandings of acid strength: How meaningful is reliability when measuring alternative conceptions? J. Chem. Educ. 2014, 92, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Griethuijsen, R.A.L.F.; van Eijck, M.W.; Haste, H.; den Brok, P.J.; Skinner, N.C.; Mansour, N.; Gencer, A.S.; BouJaoude, S. Global patterns in students’ views of science and interest in science. Res. Sci. Educ. 2014, 45, 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, R.; Akmal, T.; Petrie, K. Development of a cognition-priming model describing learning in a STEM classroom. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2015, 52, 410–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohl, W. Sustainable landscape use and aesthetic perception–Preliminary reflections on future landscape aesthetics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 54, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A. Methodology influences on destination image: The case of Michigan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 480–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Ekinci, Y.; Uysal, M. Destination image personality: An application of branding theories to tourism places. J. Bus. Res 2006, 59, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J.; Dowling, R.; Cowan, E. Wine tourism marketing issues in Australia. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1998, 10, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.R. Wine Tourism in New Zealand: A National Survey of Wineries 1997; Unpublished doctoral dissertation; University of Otago: Dunedin, New Zealand, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, D. Georgian Feast-The Vibrant Culture and Savor: The Vibrant Culture and Savory Food of the Republic of Georgia; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tstatava, D. გასტრონომიული ტურიზმი და გასტრონომიული ტურისტი. 2016. Available online: http://culinartmagazine.com (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Pearce, D.G. Toward an integrative conceptual framework destination. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Demographic Profile | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 124 | 54.6 |

| Female | 103 | 45.4 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–25 | 15 | 6.6 |

| 26–35 | 64 | 28.2 |

| 36–45 | 22 | 9.7 |

| 46–55 | 31 | 13.7 |

| 56–65 | 39 | 17.2 |

| 66 years and older | 56 | 24.7 |

| Education level | ||

| High school and vocational school | 65 | 28.6 |

| Undergraduate degree (Bachelor’s degree) | 43 | 18.9 |

| Post-graduate degree (Master’s/PhD degree) | 119 | 52.4 |

| Frequency of wine consumption | ||

| Several times a week | 106 | 46.7 |

| About once a week | 73 | 32.2 |

| About once a month | 28 | 12.3 |

| Rarely | 17 | 7.5 |

| Never | 3 | 1.3 |

| Factors | Factor Loading | Mean | Standard Deviation | Grand Mean | Eigen Value | Cronbach’s Alpha | Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonic related country image | 4.26 | 2.95 | 0.67 | 56.55% | |||

| Georgia is known for its hospitality | 0.90 | 4.33 | 0.85 | ||||

| Georgia is known for its long tradition as a wine-growing country | 0.73 | 4.19 | 0.84 | ||||

| Aesthetic related country image | 4.25 | 1.05 | 0.60 | 17.28% | |||

| Georgia is known for its charming landscape and nature | 0.92 | 4.06 | 0.75 | ||||

| Georgia is known as a cultural nation | 0.65 | 4.44 | 0.71 | ||||

| Total variance explained | 73.83% |

| Factors | Factor Loading | Mean | Standard Deviation | Grand Mean | Eigen Value | Cronbach’s Alpha | Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edutainment (passive, active participation) | 4.03 | 6.17 | 0.63 | 31.84% | |||

| To learn more about Georgian wine | 0.75 | 3.97 | 0.91 | ||||

| To experience the Georgian feast tradition | 0.72 | 3.67 | 0.94 | ||||

| To experience local cuisine/food | 0.69 | 4.30 | 0.79 | ||||

| To learn more about local heritage and history | 0.58 | 4.19 | 0.77 | ||||

| Entertainment (passive participation) | 3.44 | 1.96 | 0.68 | 23.35% | |||

| To experience nature | 0.82 | 4.09 | 1.06 | ||||

| To relax and unwind | 0.76 | 3.65 | 0.92 | ||||

| For recreational/sporting activities | 0.74 | 2.58 | 1.13 | ||||

| Total variance explained | 55.19% |

| Factors | Factor Loading | Mean | Standard Deviation | Grand Mean | Eigen Value | Cronbach’s Alpha | Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escapism (active participation) | 2.18 | 9.17 | 0.82 | 38.03% | |||

| Biking through a vineyard | 0.83 | 2.44 | 1.23 | ||||

| Nordic walking in a vineyard | 0.81 | 2.38 | 1.22 | ||||

| Hiking in a vineyard | 0.79 | 2.02 | 1.09 | ||||

| Participating in the harvest | 0.64 | 2.41 | 1.28 | ||||

| Hiking with a winemaker | 0.62 | 1.67 | 1.01 | ||||

| Education (active participation) | 3.67 | 2.30 | 0.82 | 16.45% | |||

| Learn more about wine | 0.80 | 4.18 | 0.99 | ||||

| Meet winegrowers | 0.77 | 3.52 | 1.19 | ||||

| Learn more about wine production | 0.77 | 4.01 | 1.00 | ||||

| Wine tasting seminars | 0.77 | 3.58 | 1.26 | ||||

| Wine events / festivals | 0.54 | 3.04 | 1.29 | ||||

| Esthetic (passive participation) | 3.46 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 9.89% | |||

| Dining at a restaurant in the winery | 0.85 | 3.78 | 1.11 | ||||

| Accommodation in the winery | 0.69 | 3.14 | 1.30 | ||||

| Total variance explained | 64.36% |

| Factors | Factor Loading | Mean | Standard Deviation | Grand Mean | Eigen Value | Cronbach’s Alpha | Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wellness | 3.11 | 3.47 | 0.79 | 31.43% | |||

| A winery with a hotel complex should have an outdoor swimming pool | 0.89 | 3.09 | 1.15 | ||||

| A winery with a hotel complex should offer wellness (e.g., wine and spa) | 0.88 | 3.13 | 1.10 | ||||

| Modern | 2.86 | 2.02 | 0.45 | 18.09% | |||

| A winery should incorporate modern architecture | 0.86 | 3.09 | 1.08 | ||||

| A restaurant in the winery should offer European dishes | 0.63 | 2.63 | 1.127 | ||||

| Tradition | 4.03 | 1.52 | 0.45 | 15.40% | |||

| A winery should offer an evening of preparation of traditional Georgian dishes | 0.51 | 3.75 | 0.99 | ||||

| A restaurant in the winery should offer traditional food | 0.79 | 4.45 | 0.74 | ||||

| A winery should be built with traditional architecture | 0.71 | 3.87 | 0.96 | ||||

| Total variance explained | 64.92% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghvanidze, S.; Bitsch, L.; Elze, A.; Hanf, J.H.; Kang, S. Why Travel to Georgia? Motivations, Experiences, and Country’s Image Perceptions of Wine Tourists. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 838-854. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3040052

Ghvanidze S, Bitsch L, Elze A, Hanf JH, Kang S. Why Travel to Georgia? Motivations, Experiences, and Country’s Image Perceptions of Wine Tourists. Tourism and Hospitality. 2022; 3(4):838-854. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3040052

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhvanidze, Sophie, Linda Bitsch, Alvaro Elze, Jon H. Hanf, and Soo Kang. 2022. "Why Travel to Georgia? Motivations, Experiences, and Country’s Image Perceptions of Wine Tourists" Tourism and Hospitality 3, no. 4: 838-854. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3040052

APA StyleGhvanidze, S., Bitsch, L., Elze, A., Hanf, J. H., & Kang, S. (2022). Why Travel to Georgia? Motivations, Experiences, and Country’s Image Perceptions of Wine Tourists. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(4), 838-854. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3040052