1. Introduction

The creation of a common sense of place among stakeholders and citizens in border areas is linked to fundamental challenges, namely, geographical characteristics, language, tradition, politics, local vernacular, etc., which should be considered when planning a cross-border (c-b) strategy. In the case of a common place branding strategy or destination marketing strategy, these challenges lead to a holistic strategic approach to overcome difficulties. Methodologically, a practical approach has to be followed to plan a strategy recognized by all stakeholders, which leads to its successful implementation. As explained further on, this calls for online and offline tools, consultations, and the support of evidence that needs to be agreed upon. Places cannot be considered only as geographical locations but as locations connected to the sense of place developed by inhabitants, visitors, and even persons who have never been there [

1]. A destination is not only a geographical location or a natural space, but it also includes other tangible and intangible elements, such as services, attractions, infrastructure, its image, and its reputation, which are all characteristics that make the destination original and distinct. The organizational level can vary depending on the spatial limits, starting from the local, municipal, or regional levels to the national or transnational levels. Not every place automatically forms a tourist destination; if attractions or other elements can attract visitors, it constitutes an existing or potential tourist destination [

2]. Specific place features and resources attract visitors that turn these places into popular tourism destinations, usually by recognizing the destination as the purpose of the trip through spending one or more nights there [

3]. Not all places need to make the same effort to be established. For example, historic cities have an identity, which has been built and established culturally a long time ago. Efforts to introduce new destinations that are not recognized as entities or as attractive places, on the other hand, require specific steps in terms of communication pathways to reach the first level of recognition and awareness [

4,

5].

The procedure of boosting the image and fame of a specific place (an area, city, or region) through a place branding strategy focuses not only on the spatial competition for the attraction of residents, investments, and visitors, but also to create feelings of commitment and local pride in local inhabitants. Some scholars describe this as internal marketing, and, in the case of c-b areas, it can also serve the process of building a common identity or storytelling approach. As Lucarelli [

6] argues, this also comes with risks since the hybrid form of place branding within local policies can materialize positively and negatively. Additionally, place marketing/branding can also serve planning purposes or be a part of approaches with a spatial dimension (urban planning, geography, regional development, etc.) [

7]. Apart from mapping resources (cultural, historical, natural, etc.), many other tools can be used in a collaborative planning exercise, from a world cafe approach or a common evaluation exercise to consultation through online platforms with the help of special aids that allow interactions, to stakeholder representatives, to where citizens seem to be increasingly familiarized with active, participative processes. When collaborative methods are used to determine a place brand, especially with the help of online tools and social media, it is vital to create conditions of trust and use visual evidence that will be recognized by all participants [

8].

In Greece, place branding is a relatively new trend and many regions, islands, and cities, e.g., Athens, Larissa, Kozani, Chania, and Messinia, have been implementing actions with the participation of stakeholders to create a common vision on place branding [

9,

10]. In Albania, place branding efforts are mostly connected to Tirana and the most touristic areas, e.g., Vlora, Velipoja, etc. [

11]. Both countries promote a tourism development model mainly focused on coastal tourism development. In this paper, the focus is on the c-b areas of Greece and Albania, as the two countries do not share a similar legacy and evolution regarding place branding and tourism development. Despite the different tourism histories and profiles of the two countries, as a mountainous area, none of the destinations within the examined geographical area on both sides of the border can be considered popular or mature tourism destinations.

The paper aims to analyze the primary outcomes of an extended mapping exercise regarding common resources that can lead to a common place branding strategy. The survey was conducted in the context of the INTERREG-IPA CBC Project ‘Culture Branding-Strengthening Extroversion’ (‘Culture Plus’), with the University of Thessaly as a lead partner. The other partners of ‘Culture Plus’ were the Studies and Development Center (AL), the Gjirokastra Chamber of Commerce and Industry (AL), the Tourism Organization of Western Macedonia (GR), the Agricultural University of Tirana (AL), and the University of Western Macedonia (GR). In the parts of the research presented in the current paper, the following researchers, except for the authors, participated: Sotiria Katsafadou, Georgia Lalou, Neoklis Mantas, Theodore Metaxas, Lefteris Topaloglou, Pavlos Kravaris, Polikarpos Karkavitsas, Sofia Machairidou, Dr. Afroditi Kamara, Artemis Margaritidou, Alkiviadis Kyriakou, Bahri Hodja, Fatmir Guri, Vjollca Backa, Marjet Perlala. The idea of the project concerned the branding of the cross-border area of Greece–Albania through the enhancement and promotion of eco-cultural resources, focusing on tourism development. The aim is to describe and critically comment on the first steps of planning a common place branding strategy through specific actions. The practical issues, the means, and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are also commented on. Finally, an emphasis is given to the potential to follow a sustainable tourism model, aligning with the SDGs and the current post-pandemic trends in the tourism industry.

The main hypothesis to be tested was that the number/quality of the common cultural elements creates opportunities for a storytelling approach that could enforce the idea of a common brand for both sides of the border, as long as a proper consultation among stakeholders was followed.

2. Cross Border Areas, Place Branding, and Tourism Development: A Literature Review

To better understand the dynamics of attracting tourists to a cross-border area, it is essential to know how place branding is connected to this discussion, what the barriers are in c-b areas, and how the experience from other European c-b areas could operate as a benchmarking exercise. Stoffelen and Vaneste [

12] pointed out that tourism stakeholders in cross-border areas have a limited capacity to work efficiently, considering the most regional or rural development strategies. As place brands and places can be very complex, especially when involving two to more territories with different cultural or language characteristics (as in the case of border areas), stakeholder management processes become very challenging. Published works on place branding increasingly point out ownership and effective management issues when linked with identity, place branding, and destination/place management [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Hence, lately, place branding has moved away from the attraction of global business funds and competitiveness towards a more inclusive approach that is focused on ownership and participation issues [

17,

18].

A first difficulty is that any effort to create a common place brand or destination brand in a c-b area would need a general agreement between the stakeholders on both sides with open, participatory processes on the attractions, the identity, the storytelling, etc. The importance of a participatory approach and the representation of a ‘common vision’ among stakeholders and decision-makers is evident for any region; still, in a c-b area, this becomes more challenging. A key challenge is linked to agreeing on the main attractions and elements. Mapping out the common resources, namely, the cultural, environmental, economic resources, etc., is an essential but precious step to agreeing on a narrative, an identity, and a common brand that will be representative. It must be noted that mapping in this context concerns identifying and listing the resources. This also follows a current trend linked to the democratization of place branding that Aitken and Campello [

19] described through their model of the ‘4Rs’. This model refers to the social dimension of the branding process and all residents and the stakeholder groups involved in the decision-making process regarding the image, awareness, and identification of place identity. The local identity and everyday life, with their distinctive characteristics, must be represented; according to this approach, place marketing/branding is essentially based on ‘bottom up’ processes. Specifically, it focuses on dialogue, argumentative exchanges, and controversy.

Another challenge is connected to ownership, governance, and funding issues. Ownership in a cross-border area can be tricky as it involves national, regional, and local government bodies, organizations, destination management organizations, national parks, local communities, etc. This is the case of the Greek–Albanian border regions. Lovelock and Boyd [

20] suggested that cross-border collaboration should follow an inter-organizational relations approach without relying on a geographical perspective. However, any systematic destination management or place branding effort is usually an initiative of an administrative entity, such as a municipality or a region, meaning that the funding is also decided and controlled by this particular entity. This is pinpointed in the literature regarding cross-border tourism development, where evidence shows that c-b institutional ‘under-mobilization’ and ‘over-mobilization’ can become part of the problem of managing a broader c-b region in terms of governmental cooperation [

21,

22]. ICT and e-governance have a considerable impact on this process. The pandemic effects forced a quick adjustment to a digital transition that might positively impact this type of synergy. Collaborative mapping projects were usual as a practice that involved stakeholders, especially after open-source maps could be used simultaneously by different users, e.g., through Google maps [

23]. Mainstream internet users can now participate in mapping projects and share information, providing details with great accuracy.

A growing number of publications referred to the European experience throughout the past two decades of cross-border cooperation and regional development, partly drawing on the occasion of the EU-initiated INTERREG programs. A general remark that can be made is that cross-border areas in Europe include a variety of geopolitical characteristics that affect cooperation in general and tourism/branding efforts in particular. In the context of the INTERREG program, this type of approach has been at the center of many projects, and different outcomes have been documented. Critical encounters and comments on shortcomings are also pointed out. For example, Shepperd and Ioannides [

24] referred to lost opportunities that consider the expenditure on an EU level on cross-border development. Kaucic and Sohn [

25] mapped out the complexity of cross border interrelations in Europe and their prioritization through European funding. Many factors can threaten the resiliency and sustainability of cross border strategies; a political crisis or an unpredicted event can create difficulties in the everyday management of cross border exchanges and relations. This was more than evident during the COVID-19 crisis and how it affected the movement of people and goods [

26,

27].

According to the relevant literature, geography and accessibility, the political legacy, common heritage, and funding are some of the factors pointed out when referring to effective cross border branding and tourism promotion. Prokkola [

28] and Nilson et al. [

29] referred to the Scandinavian experience of cross border destinations where the particularities are connected with the favorable circumstances, e.g., the existence of the Nordic Council and the established strong connections between border areas like Sweden and Finland. The case studies of Nordkalotten, Pomerania, and Skargarden, and the role of storytelling in establishing a distinctive brand, are characteristic.They refer to common gastronomic elements or natural elements decided based on a common place branding strategy. In the Scandinavian Øresund region, the aim was to increase the residents’ sense of identity with the area. It began with the development of a bridge connecting the cities of Copenhagen (Denmark) and Malmö (Sweden). Although the Øresund region presented heterogeneities in business structures, this particularity has provided both areas with the opportunity to complement each other and work together (trade organizations, governmental administrations, and industry) to promote the region to the global markets. Three clusters were developed on information technology, medical technology, and tourism-based activities. One of the essential components of the Øresund initiative was to create a common storyline of the region, which, along with the meaning of the bridge and the use of the logo, would provide a successful branding exercise where physical identity played the critical role [

30,

31,

32].

Witte and Braun [

33] also referred to case studies where common branding strategies were discussed and promoted in Scandinavia (Øresund and Bothnian Arc) and the case of BioValley, Bodensee, Eurometropolis, and Centrope. They point out that cross-border development is a common spatial policy priority for Central Europe, especially for countries where the geographical characteristics allow easy access between border regions (e.g., Germany, France, Switzerland, etc.). The list of case studies mainly included examples of two countries involved in cross-border branding. Still, there are also examples of regions representing three countries (BioValley and Meuse–Rhine Euregio) and four countries (Bodensee and Centrope). In terms of population size, the identified initiatives range from 200,000 (Euregio Silva Nortica) to 7 million (Centrope). Studzieniecki and Mazurek [

34], based on their experience in Bug (between Poland, Belarus and Ukraine), concluded that moving towards establishing a tourism destination is a process that is probably overambitious. Thus, an “umbrella” approach, which is looser, could be more effective as a first step. The Baltic Sea region has developed an interterritorial branding initiative, including areas under the jurisdiction of various public authorities, which have joined forces to attract visitors and investors by promoting the region to foreign capital and the rise of exports. Within this effort, the strong engagement on the side of multiple organizations, especially on using branding approaches to provide further visibility to the region and improve its identity and image to its external environment, can be seen as a very positive outcome [

35]. The Great Geneva (Grand Genève), a cross-border agglomeration, has highlighted some critical aspects of cross-border branding. These show the need for integrating a series of brands and sub-brands, based on the different area characteristics, their residents, the connection with the political and institutional characteristics of the involved areas, and the incorporation of the role of citizens [

36,

37]. Finally, the Euroregion Galicia–northern Portugal has been promoted by the European Union to enhance cross-border cooperations, including the territories between the Bay of Biscay (northwest Spain) and the River Douro (northern Portugal). To this end, a joint cross-border spatial planning strategy could be the starting point for promoting innovation, creativity, authenticity, policymaking, international relations, public diplomacy, investment, export promotion, tourism, and cultural relations, as well as achieving cost-effectiveness when designing a joint promotional campaign [

37].

In most cases, the objectives are met; still, in c-b areas, political relations, management issues, funding difficulties, unforeseen events, etc., can create drawbacks. Seric and Vitner-Markovic [

38] referred to a cross-border branding effort in the Karlovac County (Croatia) and Southeast Slovenia based on the area’s cultural and natural heritage (the Kupa/Kolpa River, caves, natural and cultural architecture, castles, forts, old towns, traditions, etc.). Still, while this could lead to a long-term place branding or tourism management plan, or the establishment of a destination management organization (DMO), as in another case, this was not possible. However, the role of common heritage proved to be a positive element, which is also the case in many other c-b areas, e.g., in the Danube border areas [

39].

3. The Methodology of Planning a Common Place Branding for the Greek–Albanian c-b Area

Applying place branding and destination management practices in c-b areas can be complicated and demanding. Still, it can also become part of an effort to create connections, positive c-b communications, and synergies [

40,

41,

42]. In the case of the Greek–Albanian c-b areas, the latter is evident; however, many particularities apply:

- (a)

Greece shares borders with four countries (Albania, Northern Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Turkey). Tourism plays a crucial role in most of the c-b areas, while geopolitical tensions and events affect the tourism industry, e.g., the refugee crisis on the islands of Lesvos and Chios [

43]. Destinations close to the Greek–Albanian border, Ioannina and Kastoria, are typical destinations with a particular attractiveness factor: their waterfront on the lake. Ioannina is a city that mainly attracts domestic tourists. At the same time, Kastoria in Western Macedonia is a typical example of a city that is very much affected by car tourism and unexpected events, e.g., the closing of the borders due to COVID-19 restrictions have a substantial effect on tourism flows [

44,

45]. In the case of the cross-border area of Greece and Albania, the first steps for common activities in the tourism sector are still to be made. Thus, it is an opportunity to compare the Greece–Albania border area to other European border areas with similar geophysical characteristics. The area’s current, somewhat undermined image is incompatible with its essential qualities and potential. These are areas of high natural value and various tangible and intangible heritage assets, which are underestimated and are not recognized as key attractions.

- (b)

Due to the pre-accession status of Albania in the EU, and for historical reasons, the common European identity is also not yet prominent in the cross-border area. The border lies more as a boundary between different states and cultures, rather than a common European territory between the neighboring countries with similar cultural resources. As a result, the common identity and cultural elements of the Greek–Albanian c-b areas have not been adequately promoted until now, nor do they lead to the recognition of a tourism destination.

The methodology was primarily based on a common mapping exercise concerning the essential eco-cultural resources, followed by evaluating of their importance regarding the common identities of the participating areas in Albania and Greece. This led to the first common understanding exercise that created a branding strategy discussion preconditions. A consultation process followed. Methodologically, a basic template has been created to proceed with the initial mapping exercise, which was then assessed based on the importance of each asset as a common element for communities on both sides of the border. In addition to this, primary data from local visits was used, as well as interviews with representatives of stakeholders organized alongside a consultation process between 2019 and 2021. Part of the outcomes and key lessons learnt are presented and discussed in this paper.

The method used for finding and recording the resources was a content analysis of studies, texts, documents, reports, websites, and social media pages, along with meetings with key local stakeholders (five meetings in Greece and three meetings in Albania). The resources were recorded by category after identifying three main domains as the categories for the eco-cultural resources: (1) natural and wildlife resources, (2) tangible cultural heritage, and (3) intangible cultural heritage. The recorded resources (61 in Greece and 25 in Albania, or 86 in total) were then analyzed and critically evaluated for those which can indicate the brand awareness to be highlighted. The criteria for this critical evaluation was the following: (1) the administrative status and legal regime, (2) the level of tourism development, (3) the contribution to the local or regional economy, (4) the potential of inclusion in a branding strategy, and (5) the promotion through sites or social media. The selected evaluation method was attributed (0 to 3) to each criterion.

The methods used for collecting the data were:

Discussions with the managing authority of each resource (or with local executives in the absence of a managing authority);

Structured interviews with elected officials with the responsibility for place branding and tourism development (ten interviews in Greece and four interviews in Albania);

Discussion meetings with the representatives of local stakeholders (three meetings in Greece and two meetings in Albania);

Open consultations with residents and stakeholders (a GOAP procedure in Greece and an online open consultation due to Albania’s pandemic) [

37,

38].

The main hypothesis to be tested was that the number/quality of common cultural elements creates opportunities for storytelling that could enforce the idea of a common branding approach for both sides of the border, as long as a proper consultation among stakeholders is followed. The main issues were the “difficult” geographical characteristics and poor access, the lack of c-b partnerships, and the pandemic crisis during the research phase. Unlike other European border areas with common geophysical characteristics, the previous potentials have not yet been exploited. However, they should form a vehicle towards establishing a new identity aimed at tourism development. Because of the geography and political factors, access issues create extra difficulties.

An issue that also created difficulties was the geography of the research area. The areas participating in the project serve as case studies for the geographical units of the whole cross-border area. They do not form one greater geographical area that can be considered an entity. Gjirokastra is located on the northwest border, whereas Kastoria and Florina are located in the southeast. This option serves as a better representation of the entire cross-border area. Still, it does not facilitate the identification of common resources, at least geomorphologically, as would be the case if the areas were precisely adjacent to each other. On the other hand, identifying common resources at both ends of the cross-border area would provide strong evidence for their presence in the broader area, reinforcing the role they can play as promotional elements.

The main research questions were the following:

How do existing internal and external promotion/marketing/branding efforts on each side of the border determine the outcomes of a future common branding strategy?

Which common elements can support a storytelling approach, and how can these be selected?

How can the outcomes of a common evaluation exercise comment on its use as a first step towards a common place branding strategy?

4. Resource Mapping in the Greek–Albanian Cross-Border Area

The first step in identifying the significant common eco-natural and cultural resources of the c-b Greek–Albanian area was to map and evaluate the available resources to highlight the common potential on both sides of the border. The resource mapping of the eco-cultural sector is vital in identifying the local assets since any common eco-cultural resources could form a vehicle to establish a new identity, enhancing the common European concept and sustainable tourism development [

46]. This identity can then be enhanced and formed through marketing strategies towards the whole c-b area’s rebranding.

Following the methodological principles mentioned in the previous section, the recording was separated into three main categories, which constituted the eco-cultural resources:

Natural and wildlife resources, which were considered as potential competitive characteristics of the reference area, including ecosystems related to the soil, subsoil, air, and water resources,

Tangible cultural heritage—which is an asset of great value because of its prominent contribution to the identity, creativity, and culture of any given community,

Intangible cultural heritage is often overlooked, although it includes significant assets, encompassing practices, know-how, traditions, festivities, and cultural spaces that communities recognise as part of their unique culture.

The findings of the eco-cultural resources were based on the following sources:

Studies;

Texts, documents, and reports;

Photos and videos;

Websites and social media pages;

Interviews and meetings with key local stakeholders.

The categories of the eco-cultural resources that were taken into account for recording and mapping in the case of the tangible, as opposed to the intangible, heritage is shown in

Table 1.

For mapping/recording, a template that included the following information per resource was created: (i) resource category/classification, (ii) the serial number (s/n) of the resource, (iii) the name of the resource, (iv) the region and location area, (v) the brief description, (vi) the contact information, and (vii) the website. For filling in the templates, the information was obtained through:

The integrated tourism development plan for the Region of Western Macedonia [

47];

The “Visit Western Macedonia” website;

Various internet resources according to each resource (websites of municipalities or stakeholders, tourist guides, etc.);

Studies and local development plans;

Projects related to the tourist product of the area.

The recording ended up with 61 eco-cultural resources in the Greek area and 25 resources in the Albanian area. The Greek resources are located in the Regional Unit of Kastoria (36) and the Regional Unit of Florina (25), while the resources for the Albanian area refer to the Gjirokastra district (as dictated by the areas participating in the project). The eco-cultural resources per category on both sides of the border are presented in

Table 2.

After recording all the eco-cultural resources, the next step was to analyse and critically evaluate of the qualifying ones that indicated brand awareness through consultation with local stakeholders. Interviews were conducted with the current and previous presidents of the tourism agency of Western Macedonia, the regional vice-governors of the participating spatial units, and the regional vice-governor for tourism. The findings were discussed with the representatives of local stakeholders, such as the Western Macedonia Regional Municipality Association, the Society for the Protection of Prespa, the National Reconciliation Park, and the Municipalities of Prespes, Nestorion, Kastoria, and Florina (13 interviews in total). The resulting 47 qualifying eco-cultural resources of the joint cross-border area are presented in

Table 3, with 33 resources for the Greek side and 14 resources for the Albanian side.

A more detailed categorization of the final qualifying eco-cultural resources of the cross-border area can be found in

Table 4.

The results of the critical evaluation of the resources showed that the cross-border Greek–Albanian area has a rich reserve of natural, tangible, and intangible eco-cultural resources, presenting significant biodiversity of natural ecosystems. Unique historical, archaeological, and cultural diversity characteristics can form place brands through appropriate strategic planning and branding efforts.

The unique value of the important religious monuments, particularly emphasized by their vicinities to unique mountain complexes and lake ecosystems, is a strong competitive advantage that can be exploited in tourism development. An even more promising finding is the existence of several common or contiguous resources on both sides of the border, which shows that building a common identity for the cross-border area is indeed possible and overdue. The common resources are better explored in

Section 6.

5. SWOT Analysis

The 47 qualifying assets of the c-b area were further analyzed according to the following criteria:

the administrative status and legal regime;

the level of tourism development;

the contribution to the local or regional economy;

the potential of inclusion in a branding strategy;

the promotion through sites or social media.

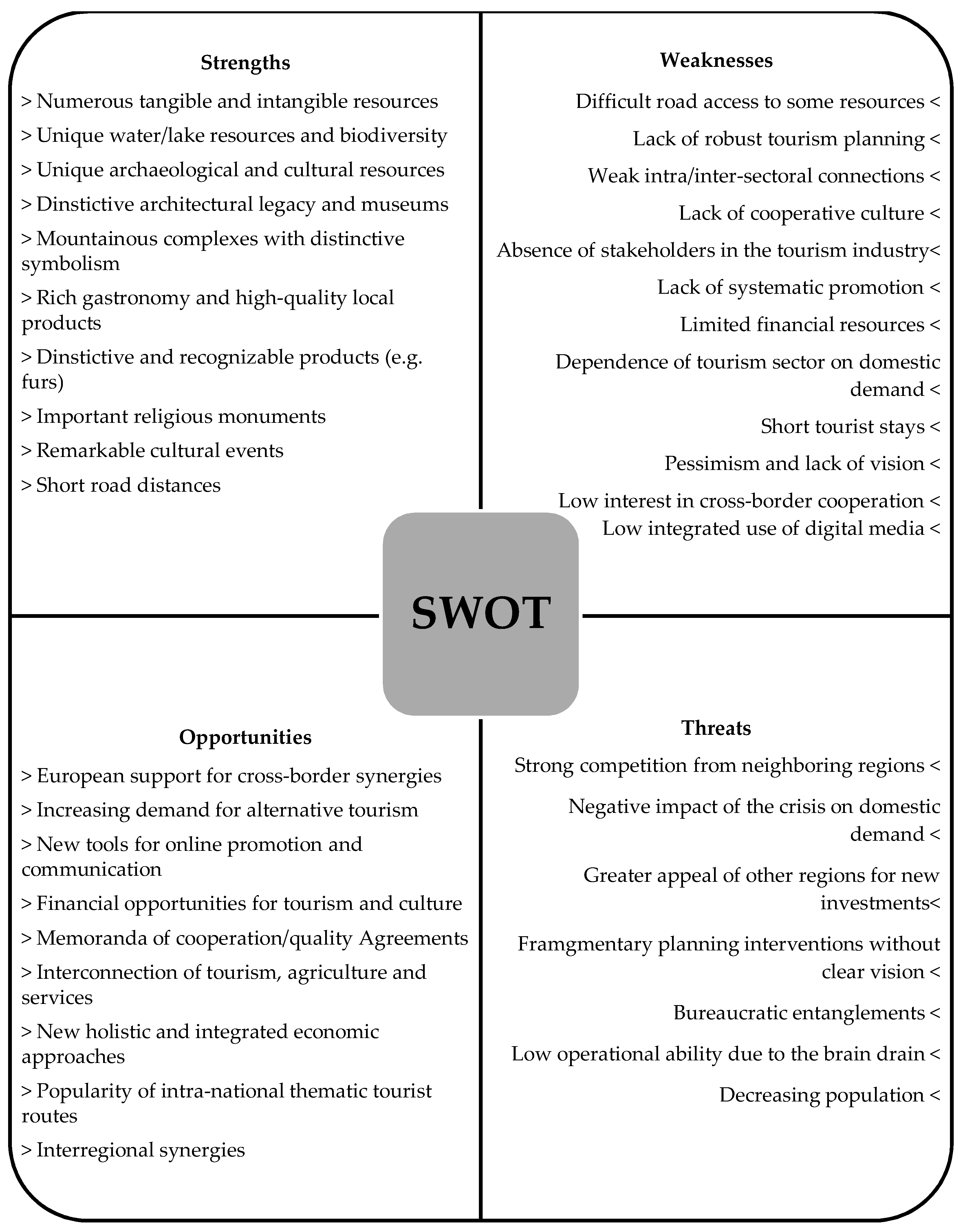

The evaluation was done either directly by the managing authorities of each resource or in collaboration with local executives who have a deep knowledge of the eco-cultural area. The results from the critical analysis were organized in a SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) for both national c-b areas, taking into account demand, recognizability, synergies, and management, to address the fundamental issues for the contribution to a new common identity. The results are presented in

Figure 1.

The reference area has significant potential due to the combination of eco-cultural wealth with unique natural resources and tangible and intangible cultural heritages. In addition, the fact that distances between the different resources are relatively short gives rise to synergies between national promotion policies and the elaboration of an integrated c-b strategy. In this context, the opportunities, such as increasing international demand for special interest forms of tourism, should be exploited. This requires a comprehensive design, new technological capabilities, and a transition to a complex mix of tourist products with high added value [

52].

On the other hand, the region’s geomorphology and the problematic accessibility of infrastructures, combined with the lack of a collaborative culture and a holistic approach of actions and policies, created a negative background that must be overcome. The typology of cross-border tourist areas provided by Timothy [

53] showed how diverse these areas could be. After all, the tourist product is offered in a highly competitive environment from other neighboring regions and countries. That is why a new identity design should take these risks into account.

Figure 1.

SWOT analysis of the Greek–Albanian cross-border area regarding eco-cultural resources [

54].

Figure 1.

SWOT analysis of the Greek–Albanian cross-border area regarding eco-cultural resources [

54].

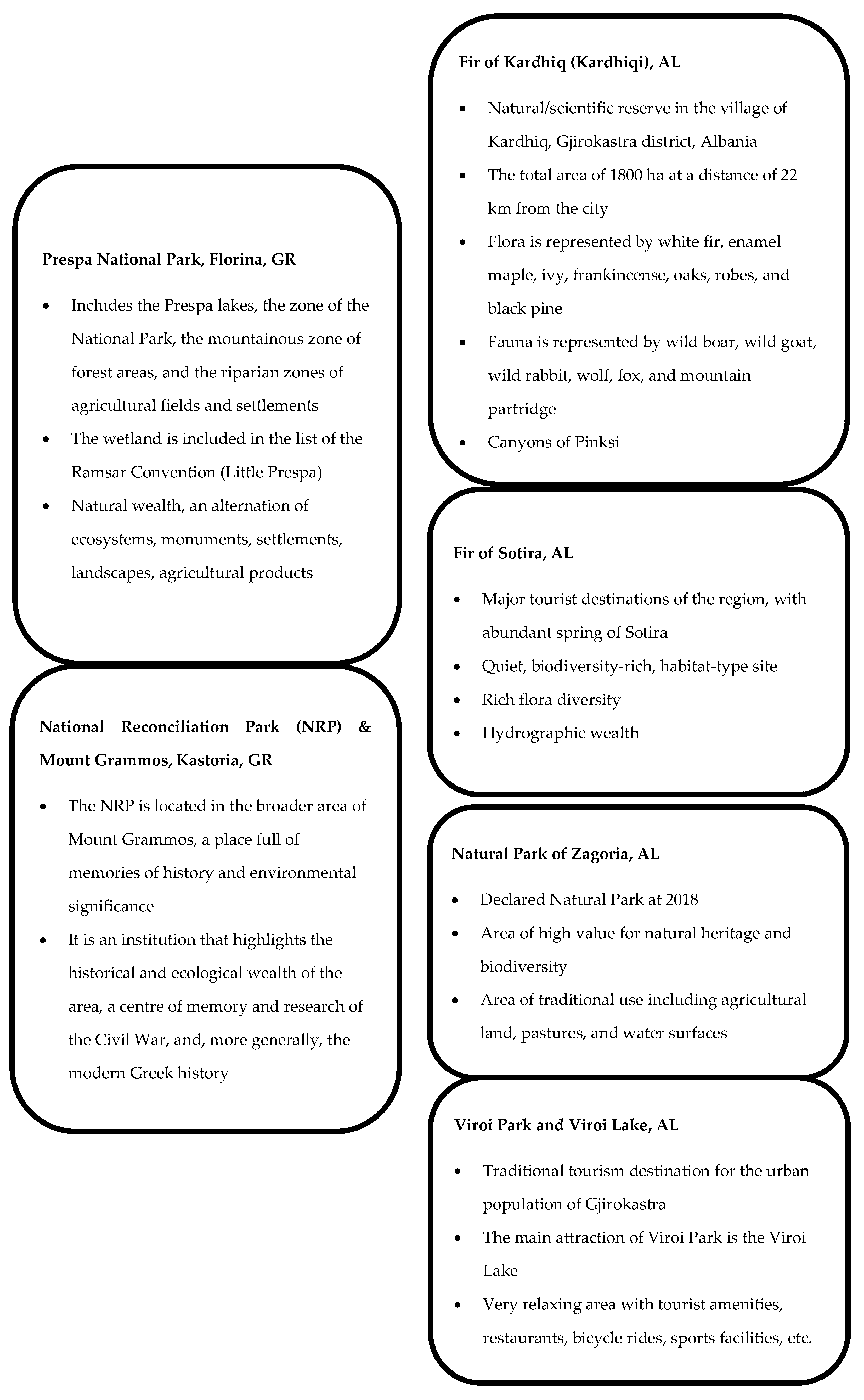

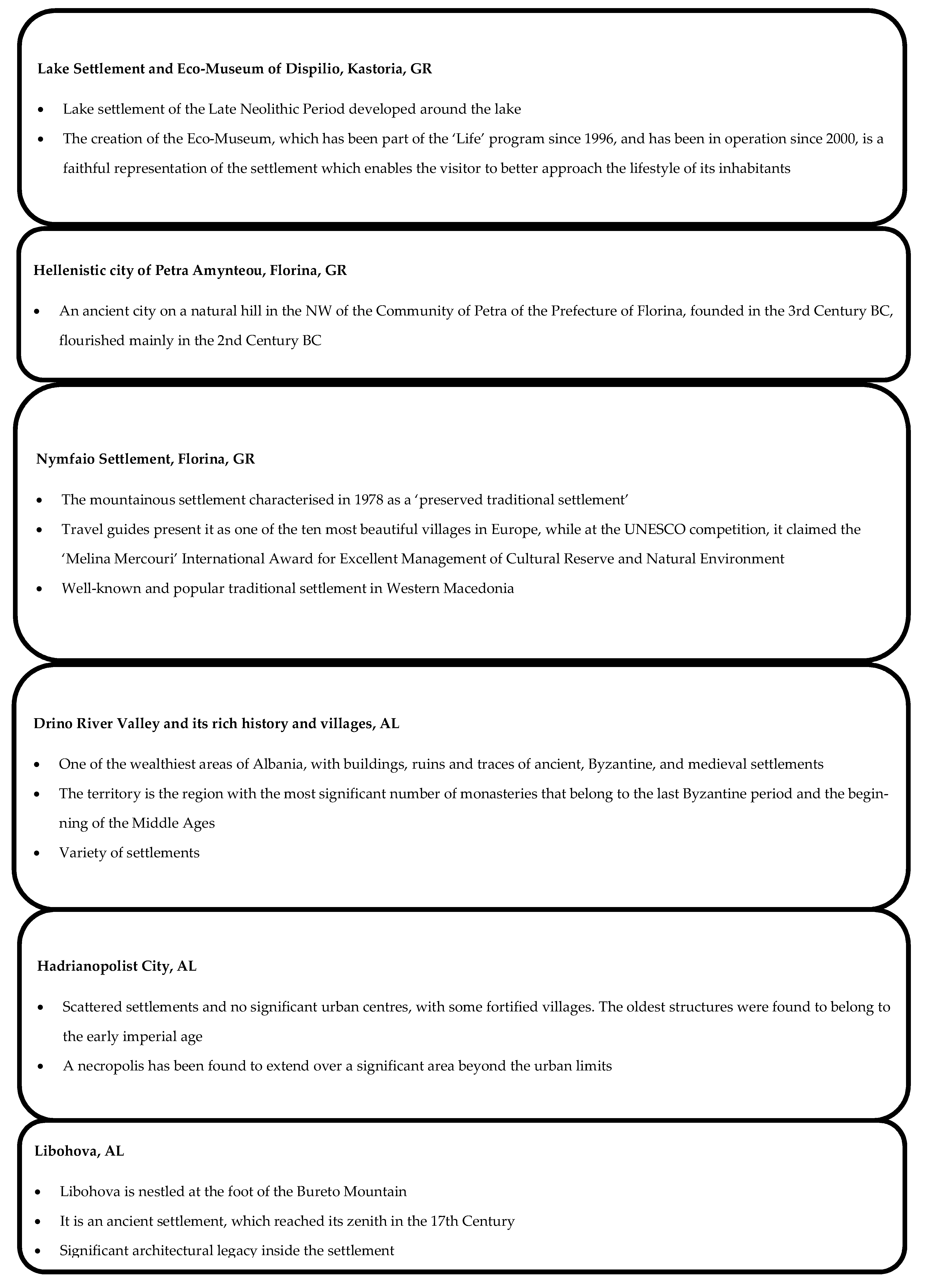

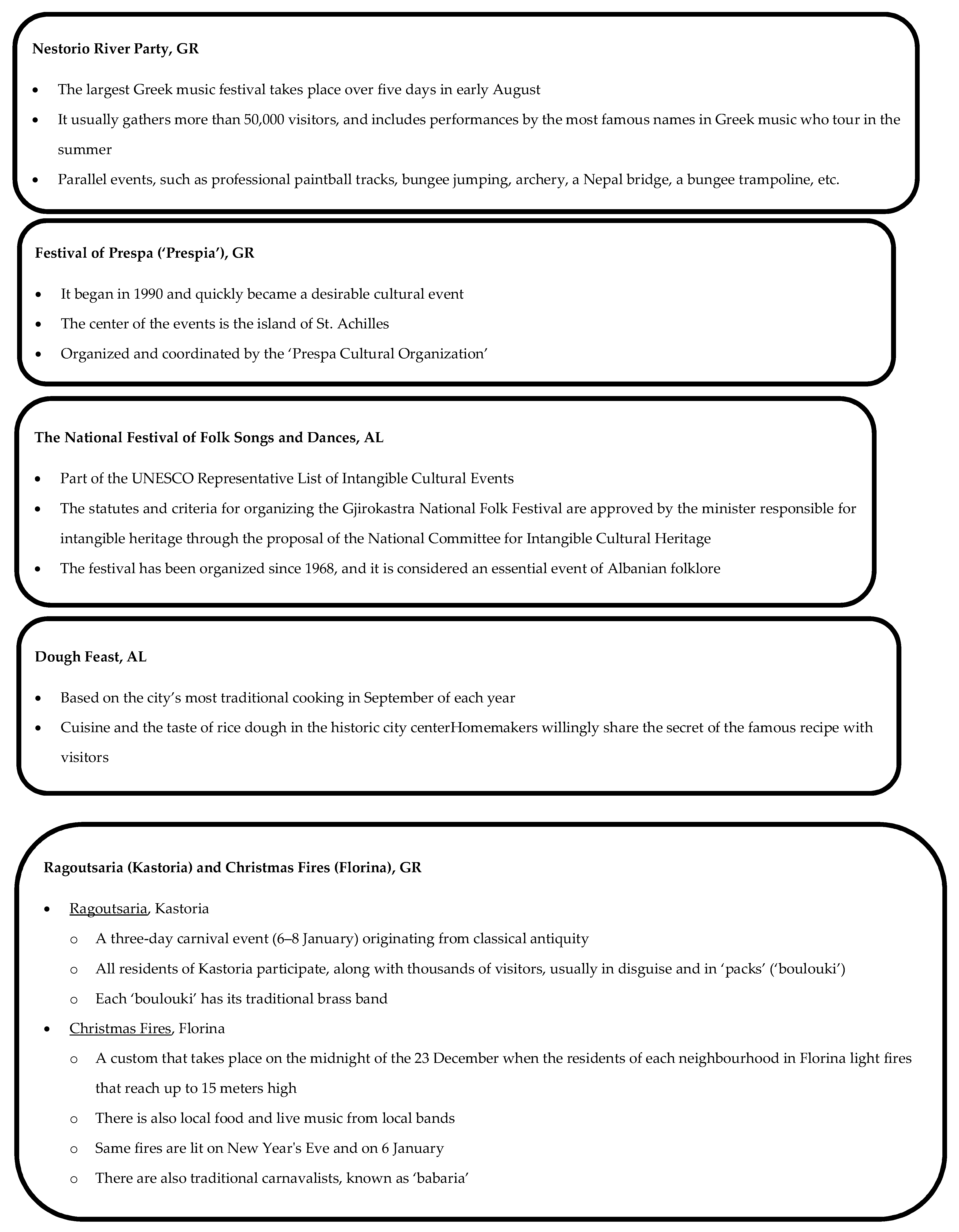

6. Common Resources that Can Support a Joint Branding Strategy for the C-B Area

The common eco-cultural resources of the cross-border area that support a joint place branding effort can be classified in the following sub-categories and are presented in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

Natural and Wildlife Resources

Tangible Cultural Heritage

Intangible Cultural Heritage

7. Results and Discussion

Through the recording and the evaluation of the resources of the participating areas both in Greece and Albania, 86 resources were recorded, of which 47 were assessed as resources of great importance. Furthermore, 20 resources among them were recognized as having a solid presence on both sides of the border and at both ends of the cross-border area. This reinforces the hypothesis that they could support the joint promotion actions aimed at the project’s central goal: Tourism development.

In terms of natural resources, the common resources relate to the categories of lakes and national parks, which are particularly important because they concern emerging special interest forms of tourism with many fans worldwide., The common resources fall into settlements and festivals in terms of cultural resources, thus covering both material and intangible cultural heritage. The festivals are unique and could address the interests of a wide range of visitors, as they cover traditional music to modern youth cultures, along with gastronomy and folk art.

It is important to note that the identified types of resources also have a strong presence in the regions of the cross-border area that are not represented in the project, emphasizing their value as reference points for the entire cross-border area. Well-known examples of this kind are the lake of Ioannina (GR) and Prespes (GR and AL), Pindos National Park (GR) and the fir of Drenova (AL), the old town and castle of Ioannina (GR), and the museums of Korça (AL). Additional examples are the festivals of the broader areas of Korça and Ioannina, which are the opposite ends of the cross-border areas represented in ‘Culture Plus’. These common resources, if used correctly, can form a solid basis for promoting the region and enhancing its image, with the ultimate goal of tourism development in the entire c-b area of Greece and Albania.

To achieve this, several challenges need to be addressed, which concern both the institutional level and the prevailing mentalities in both countries. Both countries have emphasized the tourism development of their coastal areas, only rhetorically recognizing the need to support special interest forms of tourism (e.g., mountainous tourism) without accompanying this acknowledgement with subsequent actions. Public and private investments to improve the infrastructures of the participating regions are a precondition for the development of a qualitative and modern tourist product.

At the local business level, it is also necessary to overcome the prevailing mentalities, adapt to the new standards of sustainable tourism development, and adapt to the quality of services [

36]. Moreover, the cultivation of a collaborative culture is needed, which is currently weak in both areas, either out of caution or, in the case of Albania, out of suspicion of any collectivist system for historical reasons [

42]. However, the biggest challenge is to create a common, new, and attractive narrative that will equally engage both areas and extend from the tourism product of the c-b area to the local products, to involve local entrepreneurs and actors.

The assertion of Steinecke & Herntrei [

2] that the existence of resources is the precondition for the emergence of a place as a tourist destination was adopted as the basis for the surveys after its adaptation in the case of cross-border areas. Thus, for a cross-border area to become a single tourist destination, it should have common cross-border resources. The connection of the research results with the theoretical framework is analyzed below.

The surveys highlighted the importance of the cultural resources, which prevailed as main assets in the consultation of both sides of the border, underlining the inherent significance of culture as a building block for the identity of places. This is valid, especially in cross-border areas, where it appears that the existence of common cultural elements is a precondition for the continuation of the branding efforts [

38].

The emphasis placed by Ograjensek & Cirman [

4] on the internal communication that aims to achieve recognition when trying to promote new destinations is reasonable. However, it is far from easy in the case of cross-border areas. Various issues emerged during the surveys, including the barrier of the different languages, which does not allow for joint open consultation processes. As shown in the current research, the individual consultations in the national languages undermined the attempt to establish a common identity from the outset, instead favoring strengthening local (national) identities. Thus, in the case of interregional (rather than cross-border) branding efforts, and when no language restrictions exist, it is advisable to pursue joint bottom-up procedures.

When exploring the feasibility of the suggestion by Aitken and Campello [

19] for the need for a democratization of place branding and the enhancement of the 4Rs model (directly linked to bottom-up processes, dialogue, and consultation), these were found to be particularly difficult in the cross-border areas. This reaffirmed the reservations about Lovelock & Boyd’s view [

20] that cross-border collaborations should not depend on geographical constraints. In fact, in the case of cross-border areas, geographical constraints are accompanied by administrative ones, preventing the establishment of joint developmental efforts.

From this perspective, Ambord’s [

8] focus on the online participatory processes is gaining ground since its new momentum due to the pandemic. They could be preferred in cross-border areas for organizing collaborative online consultation processes. Such processes could address the organizational difficulties and the language barrier, but the problem of dividing decision-making into administrative units with different cultures and priorities remains.

Authors like Witte and Braun [

33], Seric and Vitner-Markovic [

38], and Anderson [

35] have also pointed out the difficulties for establishing place branding and/or tourism management plans in cross-border areas, even if the challenge of joint decision-making is successfully addressed. In cross-border areas where there is no single managing authority with the jurisdiction for branding efforts (almost everywhere), the problem seems insurmountable and asks for creative and organic initiatives to be addressed.

At the management level, Euroregions appear in the literature, e.g., Oliveira [

37], as a promising European initiative in this direction, but to be a dynamic step in addressing the issue they need to strengthen their role, jurisdiction, and responsibilities. Even then, they probably would not be sufficient for cases like the one in the current paper, where the cross-border area is a European border.

8. Conclusions

Significant natural assets and resources of tangible and intangible cultural heritage can be found on both sides of the border. Some of these may be common to both Greece and Albania and, if combined with place branding tools, could form the basis for the tourism development of the area and the strengthening of the common European identity. Thus, the main hypothesis is valid, i.e., the eco-cultural resources in Greece–Albania c-b area are necessary so that their common branding could maximize positive impacts while also creating the precondition for common storytelling,

From the evaluation, one can also conclude that a sustainable tourism model that will respect the area’s natural heritage and sustain the common traditional festivities and rituals should be the cornerstone of the proposed branding strategy. The idea of “opposite ends” also serves the storytelling purposes of the strategy.

The answers to the main research questions raised in

Section 3 are the following:

Previous strategies that have been carried out and have become established do not exist. However, a future branding strategy does not depend mainly on these since place branding, in principle, relies primarily on opportunities rather than weaknesses. Thus, the fact that there are no evident existing place branding efforts can also be seen as an opportunity since any effort to determine a new narrative will be starting from scratch. Furthermore, a mentality of discussing and promoting place branding internally still needs to be developed.

The most potent common elements belong to the tangible cultural heritage (settlements, churches such as religious monuments, and architectural legacy), in quantitative and qualitative terms. Common elements belonging to natural and wildlife resources (parks) and intangible cultural heritage (festivals) are also present. Their selection has been made through their evaluation using five main criteria: the administrative status and legal regime, the level of tourism development, the contribution to the local or regional economy, the potential of inclusion in a branding strategy, and the promotion through sites or social media.

A holistic strategic approach is needed to overcome difficulties in the case of a common place branding strategy or destination marketing strategy,. The evaluated common elements that all stakeholders recognize constitutes the starting point of a common place branding strategy. However, the procedure of boosting the image and fame of a specific place through a place branding strategy should not only focus on spatial competition for the attraction of residents, investors, and visitors, but it should also aim to create feelings of commitment and local pride to local inhabitants (internal marketing).

For further research, a few questions emerged, e.g., which are the critical factors in creating and promoting a common place image for a c-b area that is difficult to promote? Which processes can be beneficial towards the establishment of a common tourism destination approach? How can tensions between different stakeholder groups be confronted?

The initial evaluation of the marketing/branding efforts pinpointed the different approaches and experiences on both sides of the border. Still, a common element was that these areas are not at the forefront of the national tourist policies, nor are they recognized as tourism destinations. Still, vital natural attractions, common traditions, and similar festivities would allow a common storytelling approach of authentic, unspoiled, sustainable tourism destinations and create a willingness for visitors from the population. Despite the obstacles, which are mostly connected to the mountainous character of these particular areas, the participants in the survey expressed a willingness to develop further the steps for a strategic marketing/branding plan.