When the Body Hurts, the Mind Suffers: Endometriosis and Mental Health

Abstract

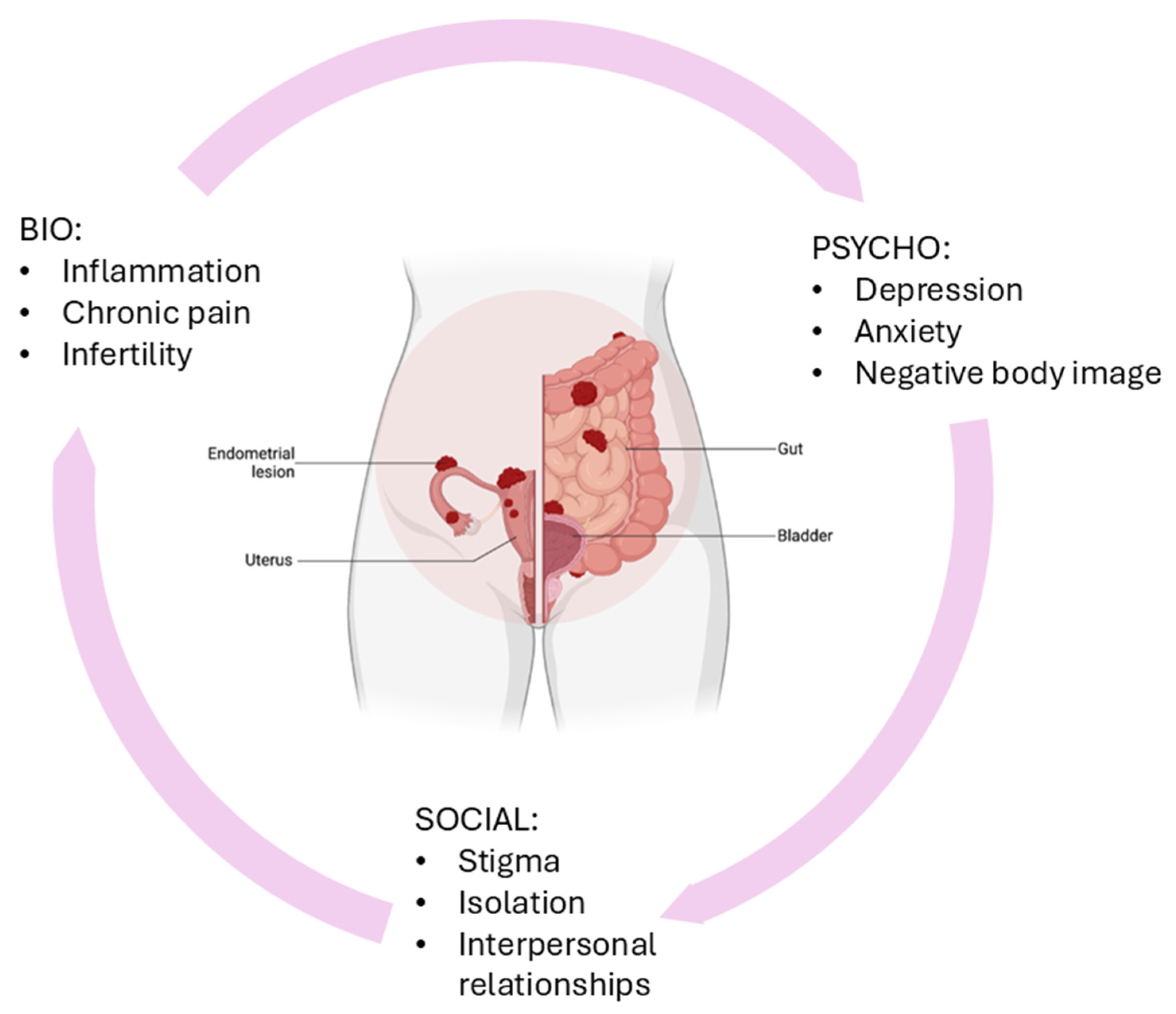

1. Introduction

2. Pathophysiology of Endometriosis and Pain Mechanisms

2.1. Pain Associated with Endometriosis

2.2. Pathogenesis of Specific Pain Patterns

2.3. Neurogenic Inflammation

2.4. Central Sensitization and Spinal Hyperalgesia

3. The Burden of Mental Health Disorders in Endometriosis

4. Management and Treatment Strategies

5. Future Directions and Research Needs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aubry, G.; Panel, P.; Thiollier, G.; Huchon, C.; Fauconnier, A. Measuring Health-Related Quali-ty of Life in Women with Endometriosis: Comparing the Clinimetric Properties of the Endo-metriosis Health Profile-5 (EHP-5) and the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D). Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, V.L.; Barra, F.; Chiofalo, B.; Platania, A.; Di Guardo, F.; Conway, F.; Di Angelo Anto-nio, S.; Lin, L.T. An Overview on the Relationship Between Endometriosis and Infertility: The Impact on Sexuality and Psychological Well-Being. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 41, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, A.W.; Missmer, S.A. Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Endometriosis. BMJ 2022, 379, e070750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfas, M.; Chisari, C.; Windgassen, S. Psychosocial Factors Associated with Pain and Health-Related Quality of Life in Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Pain 2022, 26, 1827–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauconnier, A.; Staraci, S.; Huchon, C.; Roman, H.; Panel, P.; Descamps, P. Comparison of Patient- and Physician-Based Descriptions of Symptoms of Endometriosis: A Qualitative Study. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 2686–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, P.; Berkley, K.J. Chronic Pelvic Pain and Endometriosis: Translational Evidence of the Relationship and Implications. Hum. Reprod. Update 2011, 17, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolci, C.; Jean Dit Gautier, E.; Lannez, L.; Lebuffe, G.; Wattier, J.M.; Rubod, C. Neuropathic-like Pain Affects Pain Perception in Patients with Deep Endometriosis: An Observational Study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2025, 312, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Zanden, M.; de Kok, L.; Nelen, W.L.D.M.; Braat, D.D.M.; Nap, A.W. Strengths and Weaknesses in the Diagnostic Process of Endometriosis from the Patients’ Perspective: A Focus Group Study. Diagnosis 2021, 8, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, S.; Sverrisdóttir, U.Á.; Rudnicki, M. Impact of Exercise on Pain Perception in Women with Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 1595–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martire, F.G.; Giorgi, M.; D’Abate, C.; Colombi, I.; Ginetti, A.; Cannoni, A.; Fedele, F.; Exacoustos, C.; Centini, G.; Zupi, E.; et al. Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis in Adolescence: Early Diagnosis and Possible Prevention of Disease Progression. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, O.T.; Gupta, J.; Missmer, S.A.; Aninye, I.O. Stigma and Endometriosis: A Brief Overview and Recommendations to Improve Psychosocial Well-Being and Diagnostic Delay. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toye, F.; Seers, K.; Hannink, E.; Barker, K. A Mega-Ethnography of Eleven Qualitative Evidence Syntheses Exploring the Experience of Living with Chronic Non-Malignant Pain. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toye, F.; Seers, K.; Barker, K. A Meta-Ethnography of Patients’ Experiences of Chronic Pelvic Pain: Struggling to Construct Chronic Pelvic Pain as ‘Real’. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 2713–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gstoettner, M.; Wenzl, R.; Radler, I.; Jaeger, M. “I Think to Myself ‘Why Now?’”—A Qualitative Study About Endometriosis and Pain in Austria. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 409, Erratum in BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 455. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02610-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and General Psychometric Properties. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 46, 1569–1585. [CrossRef]

- Rush, G.; Misajon, R. Examining Subjective Wellbeing and Health-Related Quality of Life in Women with Endometriosis. Health Care Women Int. 2018, 39, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Barneveld, E.; Manders, J.; van Osch, F.H.M.; Visser, L.; van Hanegem, N.; Lim, A.C.; Bongers, M.Y.; Leue, C. Depression, Anxiety, and Correlating Factors in Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Women’s Health 2022, 31, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambadauro, P.; Carli, V.; Hadlaczky, G. Depressive Symptoms Among Women with Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, C.; Schumacher, U.; Faustmann, T.; Colligs, A.; Schmitz, H.; Seitz, C. Defining a Minimal Clinically Important Difference for Endometriosis-Associated Pelvic Pain Measured on a Visual Analog Scale: Analyses of Two Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Trials. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaggioni, G.; Lia, C.; Resta, S.; Antonielli, T.; Benedetti Panici, P.; Megiorni, F.; Porpora, M.G. Are Mood and Anxiety Disorders and Alexithymia Associated with Endometriosis? A Preliminary Study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 786830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassino, S.; Pierò, A.; Boggio, S.; Piccioni, V.; Garzaro, L. Anxiety, Depression and Anger Suppression in Infertile Couples: A Controlled Study. Hum. Reprod. 2002, 17, 2986–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, F.; Riedl, D.; Fessler, S.; Wildt, L.; Walter, M.; Richter, R.; Schüßler, G.; Böttcher, B. Impact of Endometriosis on Quality of Life, Anxiety, and Depression: An Austrian Perspective. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 292, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeser, J.D.; Treede, R.D. The Kyoto Protocol of IASP Basic Pain Terminology. Pain 2008, 137, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzack, R. From the Gate to the Neuromatrix. Pain 1999, 82, S121–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, I.; Mantyh, P.W. The Cerebral Signature for Pain Perception and Its Modulation. Neuron 2007, 55, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denk, F.; McMahon, S.B. Neurobiological Basis for Pain Vulnerability: Why Me? Pain 2017, 158, S108–S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doleys, D.M. How Neuroimaging Studies Have Challenged Us to Rethink: Is Chronic Pain a Disease? J. Pain 2010, 11, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, C.J. Central Sensitization: Implications for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pain. Pain 2011, 152, S2–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, J.A. Metastatic or Embolic Endometriosis, Due to the Menstrual Dissemination of Endometrial Tissue into the Venous Circulation. Am. J. Pathol. 1927, 3, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa Bernal, M.A.; Fazleabas, A.T. The Known, the Unknown and the Future of the Pathophysiology of Endometriosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncon, J.K.; Zani, A.C.; Vieira, A.D.; Poli-Neto, O.B.; Nogueira, A.A.; Rosa-E-Silva, J.C. Endometriosis in a Patient with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser Syndrome. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 2014, 376231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, I.; Belloni, G.M.; Barbera, V.; Solima, E.; Radice, D.; Angioni, S.; Arena, S.; Bergamini, V.; Candiani, M.; Maiorana, A.; et al. “Endometriosis Treatment Italian Club” (ETIC). “Better Late Than Never but Never Late Is Better”, Especially in Young Women. A Multicenter Italian Study on Diagnostic Delay for Symptomatic Endometriosis. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2023, 28, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, T.M.; Mechsner, S. Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: The Origin of Pain and Subfertility. Cells 2021, 10, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.K.T.; Banerjee, P.; Dutta, M.; Wangdi, T.; Sharma, P.; Chaudhury, K.; Jana, S.K. Cytokines, Angiogenesis, and Extracellular Matrix Degradation Are Augmented by Oxidative Stress in Endometriosis. Ann. Lab. Med. 2020, 40, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacenti, I.; Viscardi, M.F.; Masciullo, L.; Sangiuliano, C.; Scaramuzzino, S.; Piccioni, M.G.; Muzii, L.; Benedetti Panici, P.; Porpora, M.G. Dienogest versus Continuous Oral Levonorgestrel/EE in Patients with Endometriosis: What’s the Best Choice? Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021, 37, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechsner, S. Endometriose: Eine Oft Verkannte Schmerzerkrankung [Endometriosis: An Often Unrecognized Pain Disorder]. Schmerz 2016, 30, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Feng, C.; Yang, Y.; Cui, L. Prevalence of Sleep Disturbances in Endometriosis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1405320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, J.; Barcena de Arellano, M.L.; Rüster, C.; Vercellino, G.F.; Chiantera, V.; Schneider, A.; Mechsner, S. Imbalance Between Sympathetic and Sensory Innervation in Peritoneal Endometriosis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D. Central and Peripheral Pain Generators in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain: Patient Centered Assessment and Treatment. Curr. Rheumatol. Rev. 2015, 11, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aredo, J.V.; Heyrana, K.J.; Karp, B.I.; Shah, J.P.; Stratton, P. Relating Chronic Pelvic Pain and Endometriosis to Signs of Sensitization and Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2017, 35, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- As-Sanie, S.; Harris, R.E.; Napadow, V.; Kim, J.; Neshewat, G.; Kairys, A.; Williams, D.; Clauw, D.J.; Schmidt-Wilcke, T. Changes in Regional Gray Matter Volume in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Voxel-Based Morphometry Study. Pain 2012, 153, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnoaham, K.E.; Hummelshoj, L.; Webster, P.; d’Hooghe, T.; de Cicco Nardone, F.; de Cicco Nardone, C.; Jenkinson, C.; Kennedy, S.H.; Zondervan, K.T.; World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health Consortium. Impact of Endometriosis on Quality of Life and Work Productivity: A Multicenter Study Across Ten Countries. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 366–373.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, J.A.; Huntington, A.; Wilson, H.V. The Impact of Endometriosis on Work and Social Participation. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2008, 14, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dipankar, S.P.; Kushram, B.; Unnikrishnan, P.; Gowda, J.R.; Shrivastava, R.; Daitkar, A.R.; Jaiswal, V. Psychological Distress and Quality of Life in Women With Endometriosis: A Narrative Review of Therapeutic Approaches and Challenges. Cureus 2025, 17, e80180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, S.; Esposito, F.; Abbamonte, L.H.; Anserini, P.; Remorgida, V.; Ragni, N. Quality of Sex Life in Women with Endometriosis and Deep Dyspareunia. Fertil. Steril. 2005, 83, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritzer, N.; Haas, D.; Oppelt, P.; Renner, S.; Hornung, D.; Wölfler, M.; Ulrich, U.; Fischerlehner, G.; Sillem, M.; Hudelist, G. More Than Just Bad Sex: Sexual Dysfunction and Distress in Patients with Endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 169, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluchino, N.; Wenger, J.M.; Petignat, P.; Tal, R.; Bolmont, M.; Taylor, H.S.; Bianchi-Demicheli, F. Sexual Function in Endometriosis Patients and Their Partners: Effect of the Disease and Consequences of Treatment. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de P. Sepulcri, R.; do Amaral, V.F. Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety, and Quality of Life in Women with Pelvic Endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2009, 142, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, P.S.; Bougie, O.; Pudwell, J.; Shellenberger, J.; Velez, M.P.; Murji, A. Endometriosis and Mental Health: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, 649.e1–649.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; Pathak, G.A.; Wendt, F.R.; Tylee, D.S.; Levey, D.F.; Overstreet, C.; Gelernter, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Polimanti, R. Epidemiologic and Genetic Associations of Endometriosis With Depression, Anxiety, and Eating Disorders. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2251214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, D.; Raffone, A.; Renzulli, F.; Sanna, G.; Raspollini, A.; Bertoldo, L.; Maletta, M.; Lenzi, J.; Rovero, G.; Travaglino, A.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Central Sensitization in Women with Endometriosis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 73–80.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundström, H.; Alehagen, S.; Kjølhede, P.; Berterö, C. The Double-Edged Experience of Healthcare Encounters Among Women with Endometriosis: A Qualitative Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, L.; Di Filippo, C.; Gabrielli, O.; Reppuccia, S.; La Rosa, V.L.; Ragusa, R.; Fichera, M.; Commodari, E.; Bifulco, G.; Giampaolino, P. The Burden of Endometriosis on Women’s Lifespan: A Narrative Overview on Quality of Life and Psychosocial Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.F.; Oliveira, M.A.P. Bringing Endometriosis to the Road of Contemporary Pain Science. BJOG 2025, 132, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, I.; Litta, P.; Nappi, L.; Agus, M.; Melis, G.B.; Angioni, S. Sexual Function in Women with Deep Endometriosis: Correlation with Quality of Life, Intensity of Pain, Depression, Anxiety, and Body Image. Int. J. Sex. Health 2015, 27, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlke, R.; Dahlke, M.; Zahn, V. Der Weg ins Leben: Schwangerschaft und Geburt aus ganzheitlicher Sicht; C. Bertelsmann Verlag: München, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, G.; Masoud, A.T.; Govindan, M.; Ware, K.; King, A.; Ruther, S.; Brazil, G.; Cieminski, K.; Calteux, N.; Coriell, C.; et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Gabapentin in Chronic Female Pelvic Pain Without Another Diagnosis. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2021, 2, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Carter, A.; Alexander, L.; Davé, A.; Riley, K. Holistic Approach to Care for Patients with Endometriosis. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 36, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pino-Sedeño, T.; Cabrera-Maroto, M.; Abrante-Luis, A.; González-Hernández, Y.; Ortíz Herrera, M.C. Effectiveness of Psychological Interventions in Endometriosis: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1457842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.F.; Gamboa, O.L.; Oliveira, M.A.P. Mindfulness Intervention Effect on Endometriosis-Related Pain Dimensions and Its Mediator Role on Stress and Vitality: A Path Analysis Approach. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2024, 27, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donatti, L.; Malvezzi, H.; Azevedo, B.C.; Baracat, E.C.; Podgaec, S. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Endometriosis, Psychological Based Intervention: A Systematic Review. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2022, 44, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.E.; Abdel-Shaheed, C.; Underwood, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Day, R.O.; McLachlan, A.; Eldabe, S.; Zadro, J.R.; Maher, C.G. Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of Antidepressants for Pain in Adults: Overview of Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2023, 380, e072415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Stigma and Social Identity. In Understanding Deviance: Connecting Classical and Contemporary Perspectives; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1963; pp. 256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Seear, K. The Etiquette of Endometriosis: Stigmatisation, Menstrual Concealment and the Diagnostic Delay. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Wu, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, W.; Chen, J. Effects of Progressive Muscular Relaxation Training on Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life of Endometriosis Patients Under Gonadotrophin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Therapy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 162, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcoverde, F.V.L.; Andres, M.P.; Borrelli, G.M.; Barbosa, P.A.; Abrão, M.S.; Kho, R.M. Surgery for Endometriosis Improves Major Domains of Quality of Life: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eucker, S.A.; Knisely, M.R.; Simon, C. Nonopioid Treatments for Chronic Pain—Integrating Multimodal Biopsychosocial Approaches to Pain Management. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2216482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, K.; Lowton, K.; Wright, J. What’s the Delay? A Qualitative Study of Women’s Experiences of Reaching a Diagnosis of Endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 86, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de CWilliams, A.C.; McGrigor, H. A Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Studies and Surveys of the Psychological Experience of Painful Endometriosis. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowding, C.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Skvarc, D.; Van Niekerk, L.; O’Shea, M.; Olive, L.; Druitt, M.; Evans, S. The Temporal Effect of Emotional Distress on Psychological and Physical Functioning in Endometriosis: A 12-Month Prospective Study. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2023, 15, 901–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szypłowska, M.; Tarkowski, R.; Kułak, K. The Impact of Endometriosis on Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1230303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayorinde, A.A.; Macfarlane, G.J.; Saraswat, L.; Bhattacharya, S. Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women: An Epidemiological Perspective. Womens Health 2015, 11, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.R.; Malik, A.; Roof, R.A.; Boyce, J.P.; Verma, S.K. New Approaches for Challenging Therapeutic Targets. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.S.; Giudice, L.C.; Lessey, B.A.; Abrao, M.S.; Kotarski, J.; Archer, D.F.; Diamond, M.P.; Surrey, E.; Johnson, N.P.; Watts, N.B.; et al. Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Pain with Elagolix, an Oral GnRH Antagonist. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morotti, M.; Vincent, K.; Becker, C.M. Mechanisms of Pain in Endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 209, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, M.; Sinclair, J.; Chalmers, K.J.; Smith, C.A. Self-Management Strategies Amongst Australian Women with Endometriosis: A National Online Survey. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijani, E.O.; Ajayi, L.O.; Tijani, O.S.; Akano, O.P.; Ajayi, A.F. Current and Emerging Therapies for Endometriosis-Associated Pain: A Review. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2025, 30, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeamii, V.C.; Okobi, O.E.; Wambai-Sani, H.; Perera, G.S.; Zaynieva, S.; Okonkwo, C.C.; Ohaiba, M.M.; William-Enemali, P.C.; Obodo, O.R.; Obiefuna, N.G. Revolutionizing Healthcare: How Telemedicine Is Improving Patient Outcomes and Expanding Access to Care. Cureus 2024, 16, e63881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintas-Marquès, L.; Martínez-Zamora, M.Á.; Camacho, M.; Gràcia, M.; Rius, M.; Ros, C.; Carrión, A.; Carmona, F. Central Sensitization in Patients with Deep Endometriosis. Pain Med. 2023, 24, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetera, G.E.; Merli, C.E.M.; Barbara, G.; Caia, C.; Vercellini, P. Questionnaires for the Assessment of Central Sensitization in Endometriosis: What Is the Available Evidence? A Systematic Review with a Narrative Synthesis. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 31, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentles, A.; Goodwin, E.; Bedaiwy, Y.; Marshall, N.; Yong, P.J. Nociplastic Pain in Endometriosis: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, R.; Cummins, R. What Makes Us Happy? Ten Years of the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index, 2nd ed.; Australian Unity; Deakin University: Melbourne, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Psychiatric Comorbidity | Reported Prevalence | Clinical Impact | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Up to 86% in symptomatic women | Worsens pain perception, impairs social and occupational functioning | de P. Sepulcri & do Amaral, 2009 [48]; Gambadauro et al., 2019 [18] |

| Anxiety disorders | 60–87% | Associated with diagnostic delay, anticipatory pain, and sexual dysfunction | Cavaggioni et al., 2014 [20]; Thiel et al., 2024 [49] |

| Sleep disturbances | ~50–60% | Contributes to fatigue, cognitive impairment, and poorer quality of life | Zhang et al., 2024 [37] |

| Body image disturbance | 40–55% | Linked with infertility, chronic pain, and reduced self-esteem | Melis et al., 2015 [55] |

| Sexual dysfunction (dyspareunia, reduced libido) | 50–90% depending on treatment and disease severity | Strongly affects relationship quality and psychological well-being | Ferrero et al., 2005 [45]; Pluchino et al., 2016 [47] |

| Post-traumatic stress symptoms | 20–30% (in selected samples) | Related to chronic pain and invasive procedures | Fritzer et al., 2013 [46]; Della Corte et al., 2020 [53] |

| Somatization and intrusive thoughts | Variable (30–50%) | Amplifies pain experience and psychiatric burden | Grundström et al., 2018 [52] |

| Intervention | Target Symptoms | Evidence of Efficacy | Clinical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormonal therapy (progestins, combined OCs, GnRH analogues) | Pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea | Effective in reducing cyclical pain and lesion activity | Limited long-term relief; side effects may worsen mood |

| Surgical excision of lesions | Pain, infertility | Improves quality of life and sexual function in selected cases | High recurrence rates; psychological support recommended post-surgery |

| Neuromodulators (gabapentin, pregabalin) | Central sensitization, chronic pelvic pain | Evidence of pain modulation in refractory cases | Use with caution; variable efficacy |

| Antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs) | Depression, anxiety, pain modulation | Effective for psychiatric symptoms and pain perception | Requires psychiatric supervision |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Pain perception, anxiety, depression | Meta-analyses show significant improvement in pain and mental health outcomes | Requires trained therapist; best combined with medical therapy |

| Mindfulness-based interventions (MBSR, ACT, compassion-focused therapy) | Stress, emotional regulation | Reduces perceived stress, enhances coping | Growing evidence base; promising adjunctive role |

| Progressive muscle relaxation/physiotherapy | Anxiety, pelvic floor dysfunction, dyspareunia | Improves sexual function and quality of life | Useful as part of rehabilitation |

| Multidisciplinary care models | Global quality of life, psychosocial burden | Associated with improved satisfaction, adherence, and outcomes | Requires integration of gynecologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, physiotherapists |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Marano, G.; d’Abate, C.; Ianes, I.; Costantini, E.; Lisci, F.M.; Traversi, G.; Gaetani, E.; Napolitano, D.; Mazza, M. When the Body Hurts, the Mind Suffers: Endometriosis and Mental Health. Psychiatry Int. 2026, 7, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010009

Marano G, d’Abate C, Ianes I, Costantini E, Lisci FM, Traversi G, Gaetani E, Napolitano D, Mazza M. When the Body Hurts, the Mind Suffers: Endometriosis and Mental Health. Psychiatry International. 2026; 7(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarano, Giuseppe, Claudia d’Abate, Ilaria Ianes, Eugenia Costantini, Francesco Maria Lisci, Gianandrea Traversi, Eleonora Gaetani, Daniele Napolitano, and Marianna Mazza. 2026. "When the Body Hurts, the Mind Suffers: Endometriosis and Mental Health" Psychiatry International 7, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010009

APA StyleMarano, G., d’Abate, C., Ianes, I., Costantini, E., Lisci, F. M., Traversi, G., Gaetani, E., Napolitano, D., & Mazza, M. (2026). When the Body Hurts, the Mind Suffers: Endometriosis and Mental Health. Psychiatry International, 7(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010009