Abstract

Person-centered care emphasizes shared decision-making and a holistic approach to support patient autonomy. This scoping review aimed to clarify the definitions and approaches of person-centered physical rehabilitation (PCPR) that satisfy patients with schizophrenia and to identify specific methods to increase their satisfaction. Methods: This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Joanna Briggs Institute and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist. The studies were screened, the data were extracted, and the findings were charted. Results: PCPR is an individually optimized rehabilitation approach that is centered around the “person” and is aimed at supporting the entire life of the individual, while respecting their values and wishes. This approach emphasizes the importance of patients actively participating in their own treatment and enhancing their self-management abilities rather than relying solely on medical techniques. PCPR involves empowering patients, particularly patients with schizophrenia; establishing comprehensive rehabilitation plans; and adopting flexible responses. Conclusions: Effective PCPR enhances healthcare providers’ moral sensitivity and ability to manage complex needs, thereby improving patient satisfaction and motivation to join physical rehabilitation. Furthermore, to conduct PCPR for patients with schizophrenia effectively, it is crucial to provide not only physical rehabilitation, but also appropriate psychosocial support, and to promote the establishment and maintenance of healthy lifestyle habits.

1. Introduction

Patient-centered care is defined as care that respects and responds to the patient’s preferences, needs, and values and ensures that the patient’s values guide all clinical decisions [1]. This model treats patients as partners by involving them in the planning of treatment goals and supporting them in taking responsibility for their health. A systematic review of patient- and family-centered care revealed that this model improved quality of life through better health management and knowledge. It also reduces anxiety and depression and shortens the length of hospital stays, while boosting healthcare providers’ satisfaction and confidence [2]. The traditional healthcare model places physicians and other healthcare professionals in the primary decision-making role, and patients comply with their medical advice. However, in the patient-centered care model, decisive power is shared and centered around the patient’s wishes. This approach focuses on understanding patients and their unique circumstances as a form of care provision [3]. However, the effect of patient-centered care on patient autonomy may be challenging to achieve among patients with chronic illness and distinct treatment goals [4], particularly those with chronic schizophrenia who require long-term support [5].

PCC is a shift from a traditional medical model to one that supports individual choices and autonomy [6]. Unlike the traditional approach, PCC focuses on the entire person [7]. In addition to providing medical care, it has to be a holistic (biopsychosocial–spiritual) approach to delivering care [3]. The PCC model is particularly useful for older adults and those with chronic illnesses and functional limitations [8].

A study found that the adoption of PCC in community mental health and rehabilitation clinics enhanced care delivery and improved mental health workers’ moral sensitivity and ability to address the complex needs of patients [9]. Furthermore, this approach increased patient satisfaction [10]. However, effective training using this model requires a philosophical shift and technical skills, because rehabilitation goals must be designed with the patient [11]. Similar benefits have been observed in maintaining the health and quality of life of people with dementia, as well as in reducing agitation, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and depression [12]. PCC facilitates the collaborative development of a recovery-oriented plan based on life goals.

PCC in psychiatry emphasizes a holistic understanding of a patient’s values, social contexts, and lived experiences, thus distinguishing this approach from personalized and precision medicine. Personalized and precision medicine have profoundly influenced healthcare by promoting individualized treatment strategies based on genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors [13]. Studies collectively highlight the promise and challenges of implementing it in psychiatry. Precision medicine seeks to replace trial-and-error approaches with data-driven, neurogenic, and individualized care strategies by using biomarkers [14]. The limitations of standardized diagnostics and randomized trials highlight the need for a more person-centered approach that considers patients’ lived experiences and preferences [15]. Personalized and precision medicine are recent strategies, and caution with their use should be emphasized, because real-world applications remain complex owing to the multifaceted nature of psychiatric disorders [16].

Personalized medicine focuses on tailoring treatment to individual characteristics, whereas evidence-based medicine overlooks the nuanced, context-driven nature of patient care; therefore, personalized medicine is a more philosophically and clinically appropriate alternative [17]. Furthermore, the central role of digital patient records in personalized medicine emphasizes how integrated, data-rich profiles can enhance diagnosis, treatment, and prevention [18].

PCC and biologically based models stem from different paradigms; precision medicine ensures scientifically optimized interventions, whereas PCC ensures that these interventions are ethically and contextually meaningful [19]. PCC adopts a holistic view of the patient by valuing their experiences, preferences, and social contexts and fostering shared decision-making and empathetic communication [20]. Integrating these frameworks is particularly important in the treatment of mental health and chronic illness, where cultural identity and psychosocial complexity profoundly shape treatment outcomes.

Barriers to PCC in rehabilitation include uncooperative organizations and leadership, staff constraints, heavy workloads, and resistance to change. Meanwhile, PCC is enabled by good leadership, staff satisfaction, a favorable physical environment, training, education, and collaborative decision-making [21].

Psychiatric rehabilitation emphasizes person-centered, evidence-based practices that are designed to support the recovery of individuals experiencing mental health challenges. It aims to enhance and maintain adaptive skills while supporting the achievement and sustainability of personally meaningful and valued social roles [22]. Studies have examined the satisfaction of psychiatric inpatients on the level of care they received [23,24] and reported that higher satisfaction was associated with older age, employment, living with others, having close friends, having fewer severe illnesses, and being hospitalized for the first time. In contrast, lower satisfaction was linked to higher educational attainment, comorbid personality disorders, and involuntary hospitalization [25].

Despite pharmacological and psychosocial interventions, schizophrenia remains a leading cause of disability. It is also considered a life-shortening illness because it leads to poor physical health and its complications. Schizophrenia has been described as a syndrome of accelerated aging [26]. Physical therapy should be initiated earlier to address the resulting limitations in physical status and impairments in activities of daily living. Thus, people with schizophrenia should be recognized as important individuals who can benefit from physical rehabilitation.

Physical rehabilitation is a safe and important approach for improving the health and well-being of people with schizophrenia [26,27]. Physical therapy approaches might be able to improve the mental and physical health of people with schizophrenia [28], lead to better engagement with treatment, and improve mental health outcomes [29]. However, the person-centered physical rehabilitation (PCPR) approach for people with schizophrenia still requires clear guidelines. In particular, the specific goals of person-centered physical therapy are not well-defined, and there is limited understanding of how to improve the satisfaction of patients with schizophrenia.

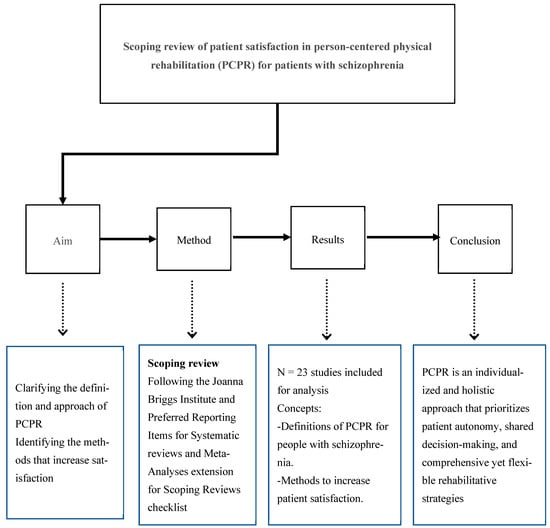

This scoping review aimed to clarify the concept of PCPR and identify effective methods for enhancing satisfaction and outcomes in patients with schizophrenia. Figure 1 shows the concepts addressed in this review.

Figure 1.

The contents of the scoping review.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Study

This study is a scoping review that explored the available literature, identified key definitions of PCC and PCPR, and identified the methods for effectively improving patient satisfaction and PCPR outcomes. Scoping reviews are used for identifying knowledge gaps, scoping a body of literature, investigating research conduct, clarifying concepts, or informing a systematic review [29]. Furthermore, this approach can identify research gaps and areas for further investigation that are critical for developing a more robust understanding of PCPR for people with schizophrenia.

2.2. Methods of the Scoping Review

This scoping review followed the recommendations of the Joanna Briggs Institute and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews: Checklist and Explanation [30]. Arksley et al. [30] reported that a scoping review is a quick summary of the main concepts underlying an area of research, the main sources of information, and the types of literature and information available. They summarized four objectives: (1) to examine the breadth, scope, and nature of the research activity; (2) to determine whether a systematic review is worth conducting; (3) to summarize and disseminate research findings; and (4) to identify research gaps in the existing body of knowledge.

In this study, five scoping review steps based on the study of Arksley et al. [30] were followed.

2.2.1. Step 1: Identifying the Research Question

For this review, two questions were formulated:

Which PCPR method is most suitable for patients with schizophrenia?

What specific methods can be used to increase the satisfaction of patients with schizophrenia?

2.2.2. Step 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using the PubMed, ScienceDirect, and ProQuest databases. The search was purposely broad and included the following concepts: (1) physical rehabilitation/physical therapy, (2) patient satisfaction, (3) psychiatric rehabilitation, and (4) patient/person-centered care. Several keywords were used to cover the four concepts: “Physical Rehabilitation,” “Psychiatric Rehabilitation,” “Mental Disorders,” “Patient Satisfaction,” and “Person-Centered Care.” The Boolean operators AND and OR were used during the initial search.

2.2.3. Step 3: Selecting the Studies (Screening)

Relevant studies were screened using Covidence (covidence.org), a web-based collaboration software platform for streamlining the production of systematic reviews and other literature reviews [31]. Abstracts from the searches were compiled and independently screened by reviewers; duplicates were eliminated. The selected studies met the following inclusion criteria: (1) articles published between 2014 and 2024; (2) articles written in English; and (3) main findings discussing at least one of these concepts, namely physical rehabilitation, patient satisfaction, psychiatric, and PCC. All studies that were considered by at least two reviewers as potentially eligible were retrieved for full-text screening [32].

2.2.4. Step 4: Charting the Data (Data Extraction and Exclusion)

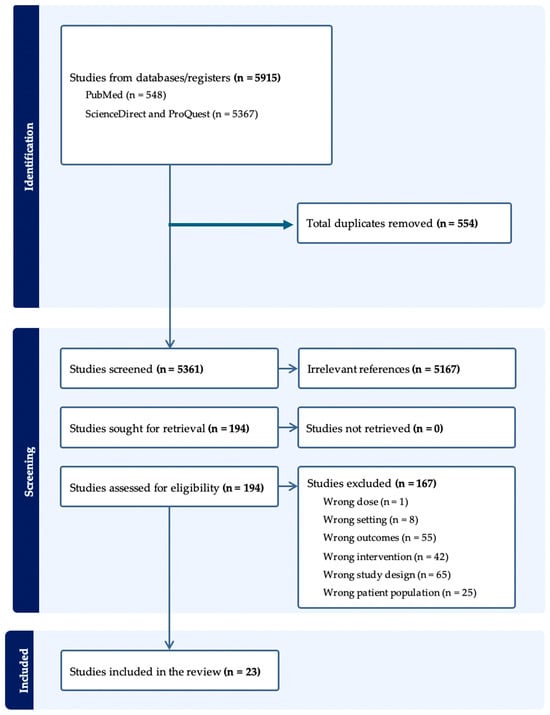

The selected articles were charted and sorted into a data extraction table. Data charting included the authors’ information, publication year, study purpose, study design, country, main findings related to this review, and themes based on the objectives of this review. The exclusion criteria included research involving animal models, psycho/social rehabilitation, and mental disorders other than schizophrenia and publications in languages other than English. Figure 2 shows an illustration of the article selection process.

Figure 2.

The article selection process.

2.2.5. Step 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Finally, all selected articles were collated and summarized. The results were organized thematically according to the following research topics: the definition of satisfactory PCPR and methods to increase the satisfaction of patients with schizophrenia.

3. Results

3.1. Published Regions, Conceptual Categories, and Categories of the Findings

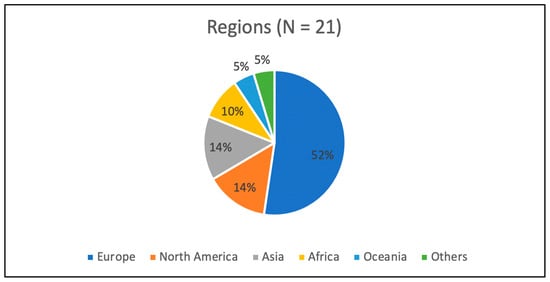

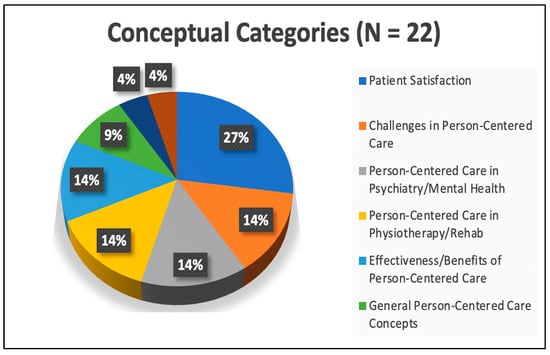

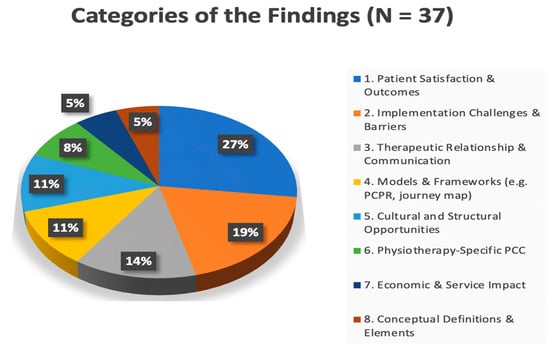

The search yielded 5915 studies, of which 23 were included in the final analysis. Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 indicate the published regions, conceptual categories, and categories of findings.

Figure 3.

The regions where the articles were published.

Figure 4.

Conceptual categories of the published articles.

Figure 5.

Categories of the findings of the published articles.

Figure 3 shows the regions where the articles were published (N = 21). Europe accounted for the largest proportion (52%; the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, the United Kingdom, Poland, Latvia, Portugal, Spain, and Estonia), followed by North America (14%; the United States and Canada), Asia (14%; Taiwan, Malaysia, and Israel), Africa (10%; South Africa and the Middle East and North Africa regions), Oceania (5%; Australia), and others (5%).

Figure 4 shows the categories of findings published in the articles (N = 22). Patient satisfaction emerged as the most frequently cited theme and appeared six times (27%). This reflects the field’s strong focus on measuring outcomes from the patient’s perspective. Challenges in PCC (14%), including implementation obstacles and institutional barriers, were mentioned three times. “PCC in Psychiatry/Mental Health (14%)” and “PCC in Physiotherapy/Rehabilitation (14%)” were both mentioned three times, thus indicating the model’s domain-specific applications. The effectiveness or benefits of PCC (14%), such as clinical improvement or cost reduction, were also cited three times. The general concepts of PCC (9%), which cover broad definitions or philosophical underpinnings, appeared twice. “Safety aspects of PCC (4%)” and “goal-setting in PCC (4%)” were each mentioned once, thus indicating that they are emerging or more narrowly defined subthemes.

Figure 5 shows the category of findings published in the articles (N = 37). The most frequently observed theme was “Patient Satisfaction and Outcomes (27%),” which appeared 10 times. This finding emphasized the positive effect of PCC on clinical outcomes, treatment adherence, and perceived care quality. The theme “Implementation Challenges and Barriers (19%)” appeared seven times, thus highlighting difficulties such as lack of training, systemic resistance, cultural mismatches, and unclear PCC definitions. The theme “Therapeutic Relationship and Communication (14%)” appeared five times and included findings about the importance of empathy, shared understanding, clear communication, and respectful interactions. The theme “Models and Frameworks (e.g., PCPR, journey map) (11%),” including the PCPR model and patient journey mapping tools, appeared four times. The theme “Cultural and Structural Opportunities (11%)” appeared four times in relation to policy support, leadership, training programs, and strategies for system-wide transformation. The theme “Physiotherapy-Specific PCC (8%)” appeared three times, thus demonstrating the relevance of PCC principles in rehabilitative disciplines. The theme “Economic and Service Effect (5%)” appeared two times, thus highlighting the reduction in service usage and improvement in cost efficiency in psychiatric care settings. The theme “Conceptual Definitions and Elements (59%)” appeared two times and included the philosophical underpinnings and foundational components of high-quality PCC.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the articles, including the study purpose, study design, country, main findings, and themes, which are based on the objectives of this review. The selected studies employed diverse methodologies, including randomized controlled trials, observational studies, scoping reviews, and cross-sectional surveys, across various countries.

The results were divided into two categories: definitions of PCPR for people with schizophrenia and methods for increasing the satisfaction of patients with schizophrenia.

3.2. Definitions of PCPR for People with Schizophrenia

The studies provided various definitions related to PCPR, which was defined as a rehabilitation approach that is individually optimized and centered around the “person” and aims to support the entire life of the individual while respecting their values and wishes [33,34]. This approach emphasizes the importance of patients actively participating in their own treatment and enhancing their self-management abilities rather than relying solely on medical techniques [35,36].

Several approaches to PCPR, including collaboration, comprehensive care planning, and flexibility, were identified. Collaboration through empowerment emphasizes the importance of patients setting their own goals and actively working toward them during the rehabilitation process [37,38]. Healthcare providers collaborate with patients to maximize their independence and aim for a self-sufficient life. Comprehensive care plans highlight the conditions under which multidisciplinary teams collaborate to establish rehabilitation plans that are tailored to individual needs and support holistic recovery. This approach involves not only healthcare providers, but also family and community members [39]. Furthermore, flexible approaches or responses are required on the basis of the patient’s condition and living environment. This includes incorporating methods such as home care and telerehabilitation to enhance patients’ quality of life [40].

Jesus et al. [41] defined PCPR as a way of thinking about and providing physical rehabilitation services “with” the person. PCPR is embedded in rehabilitation structures and practice across three levels: (1) the person–professional dyad, (2) the microsystem level (typically an interprofessional team involving significant others), and (3) the macrosystem level (organization within which rehabilitation is delivered). Melin et al. [42] focused on PCPR in physical therapy to (1) obtain an understanding of what is meaningful to the patient and (2) refine physical therapy interaction skills. Rodríguez-Nogueira et al. [43] emphasized the importance of person-centered therapeutic relationships during physical therapy interventions and outlined four critical factors: relational bonds, individualized partnerships, professional empowerment, and therapeutic communication. Additionally, PCPR principles on treating patients also highlighted the importance of empathy, advocacy, a positive attitude toward patient involvement, and managing personal distress to improve patient care [38,44]. Therefore, PCPR is associated with better social functioning and improved clinical outcomes when there is shared decision-making, which is a rights-based approach that leads to social inclusion and recovery [45].

3.3. Specific Methods to Increase the Satisfaction of Patients with Schizophrenia

Patient satisfaction emerges as a key outcome indicator. Patient satisfaction was positively correlated with treatment outcomes in both unipolar depression and schizophrenia, with higher satisfaction levels associated with better clinical improvements [46]. Patients with schizophrenia reported high satisfaction levels with PCC, with key contributing factors including personalized treatment plans, respectful communication, involvement in care decisions, clear information, emotional support, collaborative goal-setting, and respect for patient autonomy [47]. The key predictors of satisfaction included the quality of the therapeutic relationship, involvement of the patient in care planning, and perceived competence of the healthcare team [36].

Table 1.

Extracted articles on patient-centered care (PCC) and rehabilitation.

Table 1.

Extracted articles on patient-centered care (PCC) and rehabilitation.

| No. | Authors (Year) | Study Purpose | Study Design | Country | Findings | Related Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Burgers et al., 2021 [35] | To identify challenges in PCC research in general practice | Scoping review | Netherlands | Challenges include variability in definitions/measurements and difficulties in integration; need for standardized methodologies | Challenges in PCC |

| 2. | Stanhope et al., 2021 [11] | To evaluate the effectiveness of PCC planning in psychiatric settings | Randomized controlled trial | USA | Improved patient outcomes, satisfaction, engagement, and reduced healthcare costs | Effectiveness of PCC in psychiatric settings |

| 3. | Allerby et al., 2023 [47] | To evaluate the effect of PCC interventions on psychosis inpatient care | Comparative study | Sweden | Reduced healthcare consumption, personalized care plans, and increased satisfaction | The benefits of PCC |

| 4. | Köhler et al., 2015 [46] | To evaluate the relationship between patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes in patients with unipolar depression and schizophrenia | Empirical study | Germany | Positive correlation between satisfaction and treatment outcomes in depression and schizophrenia | Patient satisfaction |

| 5. | McGranahan et al., 2018 [37] | To explore the relationship between psychopathological symptoms and patient satisfaction with mental health services for schizophrenia | Observational study | United Kingdom | Severe symptoms associated with lower satisfaction; addressing symptom severity and enhancing therapeutic relationships are crucial | Patient satisfaction |

| 6. | Chen et al., 2023 [5] | To assess patient satisfaction with care for patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan | Cross-sectional survey | Taiwan | High satisfaction with personalized treatment, respectful communication, and collaborative care | PCC in psychiatric settings |

| 7. | Schoemaker et al., 2018 [48] | To identify factors associated with poor treatment satisfaction and trial discontinuation in patients with chronic schizophrenia | Observational study | South Africa | Poor satisfaction linked to medication side effects, inadequate support, and poor communication | Patient satisfaction on treatment |

| 8. | Hat et al., 2022 [36] | To identify predictors of satisfaction with care among patients undergoing treatment for schizophrenia in community mental health teams | Cross-sectional study | Poland | Key predictors: therapeutic relationship quality, care involvement, and team competence | Patient satisfaction |

| 9. | Berzina et al., 2019 [49] | To identify factors associated with patient satisfaction in mental health centers | Cross-sectional study | Latvia | Effective communication, care quality, and supportive environment enhance satisfaction | Patient satisfaction |

| 10. | Ratner et al., 2018 [33] | To identify patient satisfaction indicators or those with mental disorders | Cross-sectional survey | Israel | Key indicators: effective communication, respect, dignity, and care involvement | Patient satisfaction in severe mental disorders |

| 11. | Jesus et al., 2022 [41] | To develop a PCPR model on the basis of existing literature | Scoping review and thematic analysis | Portugal | Three-level comprehensive model: person–professional dyad, microsystem, and macrosystem | Proposing a comprehensive PCPR model |

| 12. | Philpot et al., 2019 [50] | To develop a patient-centered journey map to enhance patient experiences | Mixed-methods study | USA | Journey mapping improved patient experience and identified care enhancement opportunities | Patient satisfaction |

| 13. | Rossiter et al., 2020 [40] | To assess the effect of PCC on patient safety | Umbrella review of systematic reviews | Australia | Improved safety outcomes, reduced medical errors, and increased satisfaction | Highlighting the safety benefits of PCC |

| 14. | Hanga et al., 2017 [34] | To explore the experiences of persons with disability during initial rehabilitation needs assessment | Qualitative study | Estonia | Enhanced satisfaction through personalized assessments and care involvement | The benefits of a PCPR approach |

| 15. | Alkhaibari et al., 2023 [38] | To review the implementation of PCC in the Middle East and North Africa | Systematic literature review | Middle East and North Africa | Implementation gaps: cultural integration, awareness, resources, and communication barriers | Challenges in PCC |

| 16. | Rudnick, 2021 [51] | To provide an overview of the challenges and opportunities in implementing person-centered mental health services | Review article | International | Challenges: training gaps, systemic barriers Opportunities: improved outcomes and engagement | Challenges in PCC in mental health services |

| 17. | Rodríguez-Nogueira et al., 2020 [43] | To evaluate the psychometric properties of the Person-Centered Therapeutic Relationship Scale in physiotherapy | Validation study | Spain | Validated scale for evaluating person-centered therapeutic relationships in physiotherapy | PCC in physiotherapy |

| 18. | Bru-Luna et al., 2022 [52] | To examine how professional caregivers apply PCC in populations with mental illness | Systematic review | Spain | Improved satisfaction, adherence, and mental health; barriers include training and support gaps | PCC in mental illness and caregiving practices |

| 19. | Balqis-Ali et al., 2022 [53] | To explore the relationships between PCC prerequisites, environment, and processes | Structural equation modeling study | Malaysia | Supportive environment and well-defined processes essential for successful PCC implementation | PCC |

| 20. | Rodríguez-Nogueira et al., 2022 [44] | To explore the relationship between empathy and the physiotherapy–patient therapeutic alliance | Cross-sectional study | Spain | Strong correlation between physiotherapist empathy and therapeutic alliance strength | Patient satisfaction in physiotherapy practice |

| 21. | Grover et al., 2022 [39] | To define and provide a comprehensive understanding of PCC | Umbrella review | Canada | Identified 10 core elements, including patient rights, individualized care, and shared decision-making | PCC practices |

| 22. | Dave and Boardman, 2021 [45] | To discuss the integration of PCC in psychiatry | Perspective article | United Kingdom | Holistic approach addressing social, emotional needs improves mental healthcare outcomes | PCC in psychiatry |

| 23. | Melin et al., 2019 [42] | To analyze definitions and related requirements, processes, and operationalization of person-centered goal-setting in physiotherapy | Content analysis | Sweden | Emphasized mutual understanding and refined interaction skills in physiotherapy goal-setting | Person-centered goal-setting in physiotherapy |

4. Discussion

The findings consistently demonstrated that PCC leads to improved outcomes in psychiatric settings. Studies [47,53] revealed that PCC significantly enhanced patient satisfaction and engagement, while improving clinical outcomes. These benefits extend to reduced healthcare utilization owing to better planning, improved communication, and increased patient involvement in decision-making. Similarly, Köhler et al. [46] showed that higher patient satisfaction was closely linked to better treatment adherence and clinical outcomes in conditions such as schizophrenia, thus reinforcing the importance of incorporating PCC principles into mental healthcare.

Despite their benefits, the implementation of PCC and PCPR faces several challenges [35], such as variability in definitions and measurements, thus making it difficult to standardize and integrate PCC into practice. Systematic barriers, such as insufficient training, resource limitations, and institutional resistance to change, hinder adoption. To address these challenges, studies emphasized the importance of supportive leadership, ongoing education, and sufficient resource allocation [51,53]. Specifically, challenges to PCPR implementation were linked to the (1) professional level (services based on what the professionals can offer and not on users’ needs), (2) organizational level (rewarding efficiency instead of user outcomes), and (3) system level (not knowing the other service providers involved or what they are doing) [54]. Therefore, providing PCC- and PCPR-focused in-service education for healthcare professionals can enhance the consistency of care and rehabilitation and ensure that person-centered principles might be effectively implemented in various psychiatric physical therapy settings.

Furthermore, multiple factors influence patient satisfaction in PCC, with effective communication, empathetic therapeutic relationships, and collaborative decision-making consistently identified as key contributors [5,49]. However, negative factors, such as severe psychiatric symptoms, medication side effects, and inadequate communication with healthcare providers, were associated with low patient satisfaction [37,48]. These findings highlight the importance of integrating psychosocial support and lifestyle interventions into PCPR, particularly for patients with schizophrenia, who may require additional support to manage their condition effectively.

Two practical tools were developed to support the implementation of PCPR, including a reliable and valid Person-Centered Therapeutic Relationship Scale for assessing the quality of therapeutic relationships for physical therapy [43]. Philpot et al. [50] demonstrated the utility of patient-centered journey maps for identifying care gaps and improving patient experiences. They found that empathy—the ability to connect with and share the feelings of another person—was correlated with patient experience. Information sharing and communication between patients and providers are key facilitators of the patient experience. Context and connection refer to the ability of a care team member to meaningfully connect with the patient/caregiver, provide empathy and hope, and understand the context of a patient’s life and medical situation.

For individuals with schizophrenia, Chen et al. [5] and Hat et al. [36] highlighted specific predictors of patient satisfaction, including the perceived competence of healthcare providers and patient involvement in care decisions. These factors are essential for improving patient satisfaction, treatment adherence, and rehabilitation outcomes. However, challenges such as severe psychiatric symptoms, cognitive impairment, and communication barriers hamper the effectiveness of PCC and PCPR in achieving optimal outcomes in these patients. Collaborative efforts among physicians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, nurses, social workers, dietitians, and other mental health professionals may lead to more effective and personalized rehabilitation strategies.

The integration of PCC and PCPR principles into healthcare education and professional training has been identified as a critical enabler of effective implementation. Early exposure to PCC and PCPR concepts can foster empathy in healthcare professionals and a focus on the patient, thus ensuring that person-centered approaches are consistently applied in both psychiatric and physical rehabilitation settings.

The cultural adaptability of PCC and PCPR remains an important consideration, particularly in regions where healthcare systems face unique challenges. Reeham et al. [38] explored barriers in the Middle East and North Africa and noted that cultural nuances, stigma, and systemic limitations affected patient engagement in PCC models. These findings suggest that culturally adapted PCC and PCPR strategies, tailored educational programs, and supportive policies are necessary to improve patient satisfaction and engagement in diverse healthcare settings. Future research should explore how PCC and PCPR can be adapted to diverse cultural populations to ensure patient engagement and satisfaction.

4.1. Implications

In terms of clinical implications, healthcare providers should prioritize addressing systemic barriers, such as insufficient training, resource limitations, and institutional resistance, to optimize the implementation of PCC and PCPR. The utilization of validated assessment tools can enhance the quality of therapeutic relationships and patient experiences. Moreover, culturally sensitive adaptations of PCC and PCPR approaches are important to engage diverse patient populations more effectively. For persons with schizophrenia, collaborative multidisciplinary care involving mental health professionals and physical therapists can improve patient satisfaction, treatment adherence, and rehabilitation outcomes through personalized interventions.

The findings of this study offer several research implications. Given that physical therapy in psychiatric settings is still emerging, there remains a clear need for additional research that explicitly focuses on the effectiveness of PCPR in psychiatric populations, particularly patients with schizophrenia. Future studies should explore how PCC and PCPR models can be culturally adapted and standardized across diverse healthcare settings to enhance patient engagement globally. Research is also needed to develop and validate further practical tools and educational programs that support healthcare professionals in consistently applying person-centered principles. Longitudinal investigations into the effect of integrated multidisciplinary PCPR programs on long-term clinical outcomes and healthcare utilization in psychiatric populations would provide valuable evidence for informing best practices and policy development.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study has a few limitations that should be acknowledged.

First, studies on physical therapy within psychiatric settings, particularly those focused on PCPR, remains in its early stages. Consequently, there is a limited body of empirical evidence available, thus restricting the depth of analysis and generalizability of findings specific to PCPR in psychiatric populations, such as individuals with schizophrenia.

Second, the variability in how PCC and PCPR are defined and measured across different studies presents challenges in synthesizing results and establishing standardized best practices. Furthermore, many studies included in the review have methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes, potential selection biases, and heterogeneity of interventions, which may compromise the robustness of the conclusions.

Third, the necessity of care and rehabilitation may vary significantly depending on race, ethnicity, and gender [55,56]. There is a social perception that women with disabilities experience greater stress than men with disabilities in both their private and professional lives [57]. This study did not examine these differences.

Future research should consider such factors to optimize provision of PCPR. Finally, cultural and systemic differences across healthcare settings were not extensively examined in this study, thus limiting insights into how these factors influence the implementation and outcomes of PCC and PCPR globally. Addressing these limitations in future research will be essential for strengthening the evidence base and guiding the effective application of person-centered approaches in psychiatric physical therapy.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review defined PCPR for patients with schizophrenia and identified methods for enhancing their satisfaction. The findings indicated that PCPR can be defined as an individualized and holistic approach that prioritizes patient autonomy, shared decision-making, and comprehensive yet flexible rehabilitative strategies. Effective physical rehabilitation integrates medical, psychosocial, and functional support through multidisciplinary collaboration to improve patient engagement. PCPR in physical therapy improves the following: (1) mutual understanding of what is meaningful to the patient, (2) refinement of physical therapy interaction skills, (3) relational bonds, (4) individualized partnerships, (5) professional empowerment, and (6) therapeutic communication. Furthermore, key strategies to improve satisfaction and outcomes in patients with schizophrenia during rehabilitation include strengthening peer and family support, incorporating a structured exercise regimen, and promoting healthy lifestyle habits

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.T., K.S., F.B., A.P.B., and T.T.; methodology, R.T., K.S., F.B., and A.P.B.; validation, L.A.C.L.B., S.S., and T.T.; data curation, S.M., R.K., and Y.M.; investigation, writing—original draft preparation, R.T.; writing—review and editing, L.A.C.L.B., K.M., F.B., T.T., and S.S.; supervision, K.M.; project administration, T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCPR | Person-centered physical rehabilitation |

| PCC | Patient-centered care |

References

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; p. 10027. ISBN 978-0-309-07280-9. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Giap, T.-T.-T.; Lee, M.; Jeong, H.; Jeong, M.; Go, Y. Patient- and Family-Centered Care Interventions for Improving the Quality of Health Care: A Review of Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 87, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.; Yoder, L.H. A Concept Analysis of Person-Centered Care. J. Holist. Nurs. 2012, 30, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilo, A.M.; Dos Santos, M.C.; Gomes, A.I.; Rita, J.S. Promoting Patient-Centered Care in Chronic Disease. In Patient Centered Medicine; Sayligil, O., Ed.; InTechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-2992-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.-T.; Chueh, K.-H.; Chen, K.-C.; Chou, C.-L.; Yang, J.-J. The Satisfaction With Care of Patients With Schizophrenia in Taiwan: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Patient-Centered Care Domains. J. Nurs. Res. 2023, 31, e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, E.R.; Hollister, B.; Söderhamn, U.; Dale, B. What Matters to Older Adults? Exploring Person-centred Care during and after Transitions between Hospital and Home. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eklund, J.H.; Holmström, I.K.; Kumlin, T.; Kaminsky, E.; Skoglund, K.; Höglander, J.; Sundler, A.J.; Condén, E.; Meranius, M.S. “Same Same or Different?” A Review of Reviews of Person-Centered and Patient-Centered Care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, A.C.; Wilber, K.; Mosqueda, L. Person-Centered Care for Older Adults with Chronic Conditions and Functional Impairment: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Yi, Y. Factors Influencing Mental Health Nurses in Providing Person-Centered Care. Nurs. Ethics 2022, 29, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, D.; Choi, J. Person-Centered Rehabilitation Care and Outcomes: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 93, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, V.; Choy-Brown, M.; Williams, N.; Marcus, S.C. Implementing Person-Centered Care Planning: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Park, M. Effectiveness of Person-Centered Care on People with Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, E.A. The Precision Medicine Initiative: A New National Effort. JAMA 2015, 313, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M.H. Right Patient, Right Treatment, Right Time: Biosignatures and Precision Medicine in Depression. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demyttenaere, K. Taking the Depressed “Person” into Account before Moving into Personalized or Precision Medicine. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Perna, G.; Caldirola, D.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Nemeroff, C.B. Advancements, Challenges and Future Horizons in Personalized Psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 460–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, A.; Loughlin, M.; Polychronis, A. Evidence-based Healthcare, Clinical Knowledge and the Rise of Personalised Medicine. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2008, 14, 621–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, B.; Baek, O.K. The Next Decade: Personalized Medicine and the Digital Patient Record. In The Engines of Hippocrates; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 177–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S. Shared Decision Making—The Pinnacle of Patient-Centered Care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, I.; Swedberg, K.; Taft, C.; Lindseth, A.; Norberg, A.; Brink, E.; Carlsson, J.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Johansson, I.-L.; Kjellgren, K.; et al. Person-Centered Care—Ready for Prime Time. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2011, 10, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.B.; Vareta, D.; Fernandes, S.; Almeida, A.S.; Peças, D.; Ferreira, N.; Roldão, L. Rehabilitation Workforce Challenges to Implement Person-Centered Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenberg, M.; Rudnick, A. Recent Developments in Person-Centered Psychiatry: Present and Future Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Eur. J. Pers. Centered Healthc. 2017, 5, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, V.; Miglietta, E.; Giacco, D.; Bauer, M.; Greenberg, L.; Lorant, V.; Moskalewicz, J.; Nicaise, P.; Pfennig, A.; Ruggeri, M.; et al. Factors Associated with Satisfaction of Inpatient Psychiatric Care: A Cross Country Comparison. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, J.A.; Pavan, G.; Monteiro, R.T.; Motta, L.S.; Pacheco, M.A.; Nogueira, E.L.; Spanemberg, L. Satisfaction with Care in a Brazilian Psychiatric Inpatient Unit: Differences in Perceptions among Patients According to Type of Health Insurance. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2019, 41, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassnig, M.; Signorile, J.; Gonzalez, C.; Harvey, P.D. Physical Performance and Disability in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2014, 1, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdler, S.J.; Confino, J.E.; Woesner, M.E. Exercise as a Treatment for Schizophrenia: A Review. Psychopharmacol Bull 2019, 49, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Scheewe, T.W.; Backx, F.J.G.; Takken, T.; Jörg, F.; Van Strater, A.C.P.; Kroes, A.G.; Kahn, R.S.; Cahn, W. Exercise Therapy Improves Mental and Physical Health in Schizophrenia: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2013, 127, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Garcia, E.; Mayoral-Cleries, F.; Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.I. A Systematic Review of the Benefits of Physical Therapy within a Multidisciplinary Care Approach for People with Schizophrenia: An Update. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 229, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, Verital Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Constand, M.K.; MacDermid, J.C.; Dal Bello-Haas, V.; Law, M. Scoping Review of Patient-Centered Care Approaches in Healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, Y.; Zendjidjian, X.Y.; Mendyk, N.; Timinsky, I.; Ritsner, M.S. Patients’ Satisfaction with Hospital Health Care: Identifying Indicators for People with Severe Mental Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanga, K.; DiNitto, D.M.; Wilken, J.P.; Leppik, L. A Person-Centered Approach in Initial Rehabilitation Needs Assessment: Experiences of Persons with Disabilities. Alter 2017, 11, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgers, J.S.; van der Weijden, T. Bischoff EWMA Challenges of Research on Person-Centered Care in General Practice: A Scoping Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 669491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hat, M.; Arciszewska-Leszczuk, A.; Plencler, I.; Cechnicki, A. Predictors of Satisfaction with Care in Patients Suffering from Schizophrenia Treated Under Community Mental Health Teams. Community Ment. Health J. 2022, 58, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, R.; Hansson, L.; Priebe, S. Psychopathological Symptoms and Satisfaction with Mental Health in Patients with Schizophrenia. Psychopathology 2018, 51, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhaibari, R.A.; Smith-Merry, J.; Forsyth, R. Gianina Marie Raymundo Patient-Centered Care in the Middle East and North African Region: A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Fitzpatrick, A.; Azim, F.T.; Ariza-Vega, P.; Bellwood, P.; Burns, J.; Burton, E.; Fleig, L.; Clemson, L.; Hoppmann, C.A.; et al. Defining and Implementing Patient-Centered Care: An Umbrella Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, C.; Levett-Jones, T.; Pich, J. The Impact of Person-Centred Care on Patient Safety: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, T.S.; Papadimitriou, C.; Bright, F.A.; Kayes, N.M.; Pinho, C.S.; Cott, C.A. Person-Centered Rehabilitation Model: Framing the Concept and Practice of Person-Centered Adult Physical Rehabilitation Based on a Scoping Review and Thematic Analysis of the Literature. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melin, J.; Nordin, Å.; Feldthusen, C.; Danielsson, L. Goal-Setting in Physiotherapy: Exploring a Person-Centered Perspective. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2021, 37, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nogueira, Ó.; Balaguer, J.M.; López, A.N.; Merino, J.R.; Botella-Rico, J.-M.; Del Río-Medina, S.; Poyato, A.R.M.; Leal-Costa, C. The Psychometric Properties of the Person-Centered Therapeutic Relationship in Physiotherapy Scale. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nogueira, Ó.; Leirós-Rodríguez, R.; Pinto-Carral, A.; Álvarez-Álvarez, M.J.; Morera-Balaguer, J.; Moreno-Poyato, A.R. The Association between Empathy and the Physiotherapy–Patient Therapeutic Alliance: A Cross-sectional Study. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2022, 59, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, S.; Boardman, J. Person-Centered Care in Psychiatric Practice. Indian J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 34, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, S.; Unger, T.; Hoffmann, S.; Steinacher, B.; Fydrich, T. Patient Satisfaction with Inpatient Psychiatric Treatment and Its Relation to Treatment Outcome in Unipolar Depression and Schizophrenia. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2015, 19, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allerby, K.; Gremyr, A.; Ali, L.; Waern, M. Goulding A Increasing Person-Centeredness in Psychosis Inpatient Care: Care Consumption before and after a Person-Centered Care Intervention. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2023, 77, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoemaker, J.H.; Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M.; Emsley, R.A. Factors Associated with Poor Satisfaction with Treatment and Trial Discontinuation in Chronic Schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2019, 24, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzina, N.; Petrošina, E.; Taube, M. The Assessment of Factors Associated with Patient Satisfaction in Evaluation of Mental Health Care Center. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2021, 75, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpot, L.M.; Khokhar, B.A.; DeZutter, M.A.; Loftus, C.G.; Stehr, H.I.; Ramar, P.; Madson, L.P.; Ebbert, J.O. Creation of a Patient-Centered Journey Map to Improve the Patient Experience: A Mixed Methods Approach. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 3, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, A. Theory and Practice of Person-Centered Mental Health Services: An Overview of Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Patient-Centered Healthc. 2021, 11, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bru-Luna, L.M.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Sala, F.G. Person-Centred Care approach by professional caregivers in the population with mental illness: Systematic review. Acción Psicológica 2022, 19, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balqis-Ali, N.Z.; Saw, P.S.; Anis-Syakira, J.; Fun, W.H.; Sararaks, S.; Lee, S.W.H.; Abdullah, M. Healthcare Provider Person-Centred Practice: Relationships between Prerequisites, Care Environment and Care Processes Using Structural Equation Modelling. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forslund, L.; Arntzen, C.; Nikolaisen, M.; Gramstad, A.; Eliassen, M. Physiotherapy as Part of Collaborative and Person-Centered Rehabilitation Services: The Social Systems Constraining an Innovative Practice. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2024, 40, 2563–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Du, X.; Liu, H.; Zong, Y.; Lu, G. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation Mediates Radiation-Induced Pyroptosis in Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulappa, N.; Anderson, N.N.; Bethell, J.; Bourbonnais, A.; Kelly, F.; McMurray, J.; Rogers, H.L.; Vedel, I.; Gagliardi, A.R. How to Implement Person-Centred Care and Support for Dementia in Outpatient and Home/Community Settings: Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, I.; Strandberg, T.; Gustafsson, J. Social Representations of Gender and Their Influence in Supported Employment: Employment Specialists’ Experiences in Sweden. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 3381–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).