Mental Health in Europe After COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Adult Primary Health Care Users

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Question

- (a)

- RQ1: What are the main findings in the literature regarding the prevalence and associated factors of depression, anxiety, and stress among users of health care services in Europe?

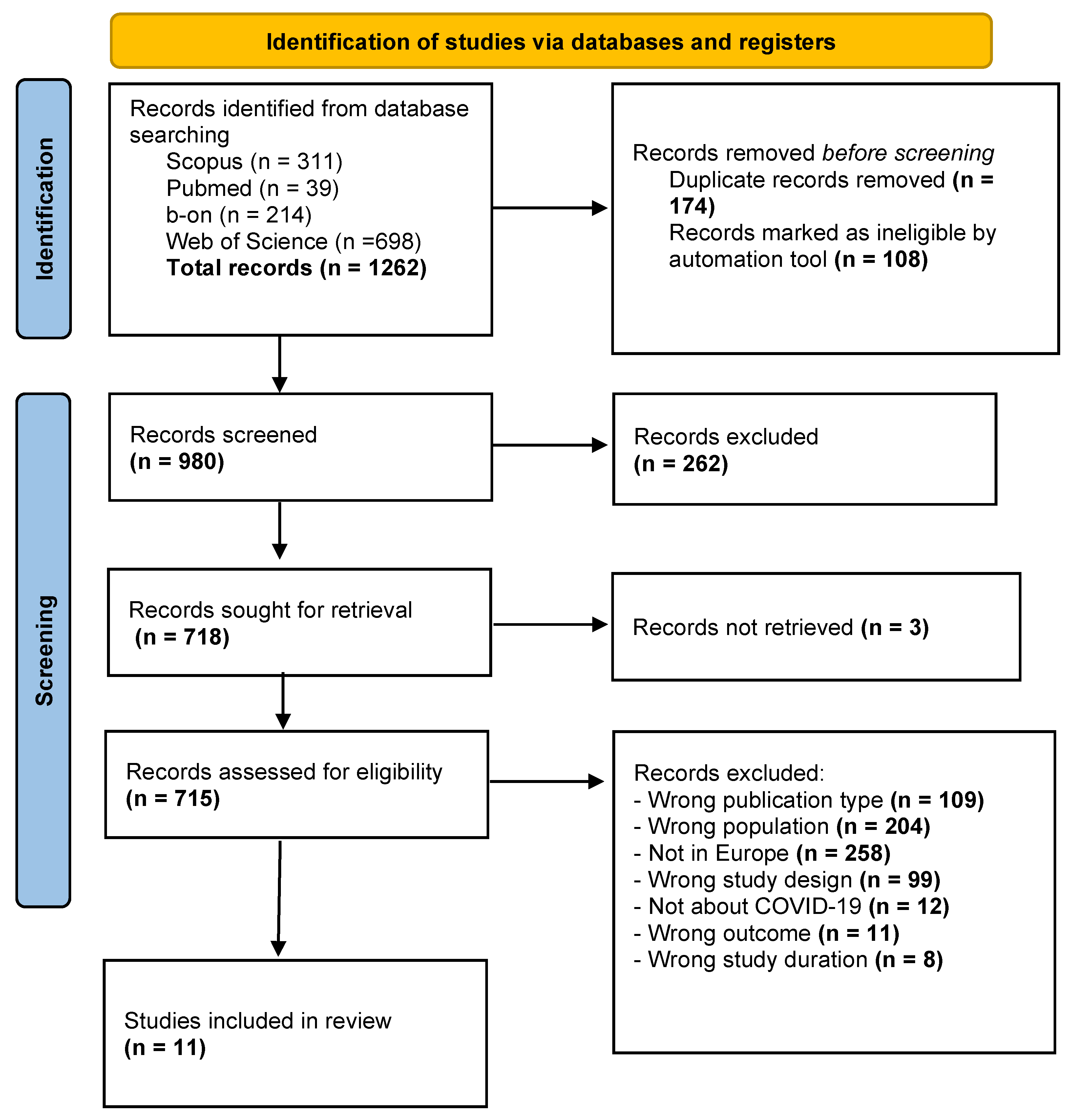

2.2. Literature Search

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Types of Outcomes Measured

- Prevalence rate

- The proportion of primary health care users presenting symptoms of depression, anxiety, and/or stress, as reported in each study.

- These prevalence rates were typically categorized by severity levels (e.g., mild, moderate, severe) when applicable.

- Associated Factors

- Sociodemographic variables (e.g., age, gender, education, employment status).

- Clinical characteristics (e.g., presence of chronic illnesses, prior mental health diagnoses).

- Psychosocial factors (e.g., social support, financial hardship, COVID-19 exposure or impact).

- Behavioural or lifestyle variables (e.g., physical activity, substance use).

- Measurement Tools: Outcomes were evaluated using validated psychometric instruments, such as:

- Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21).

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9, GAD-7).

- General Health Questionnaire (GHQ).

- Other contextually adapted or validated scales.

2.4. Screening and Eligibility Assessment

- Title and Abstract Screening: Two authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles, using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies that did not meet the criteria were excluded at this stage.

- Full-Text Review: The same reviewers retrieved and independently examined the full texts of potentially eligible studies. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer when necessary.

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk of Bias

2.7. Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Talevi, D.; Socci, V.; Carai, M.; Carnaghi, G.; Faleri, S.; Trebbi, E.; Bernardo, A.d.; Capelli, F.; Pacitti, F. Mental health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Riv. Psichiatr. 2020, 55, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Nochaiwong, S.; Ruengorn, C.; Thavorn, K.; Hutton, B.; Awiphan, R.; Phosuya, C.; Ruanta, Y.; Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T. Global Prevalence of Mental Health Issues among the General Population during the Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, S. The Need for a Consensual Definition of Mental Health. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragioti, E.; Radua, J.; Solmi, M.; Gosling, C.J.; Oliver, D.; Lascialfari, F.; Ahmed, M.; Cortese, S.; Estradé, A.; Arrondo, G.; et al. Impact of Mental Disorders on Clinical Outcomes of Physical Diseases: An Umbrella Review Assessing Population Attributable Fraction and Generalized Impact Fraction. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witteveen, A.B.; Young, S.Y.; Cuijpers, P.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Barbui, C.; Bertolini, F.; Cabello, M.; Cadorin, C.; Downes, N.; Franzoi, D.; et al. COVID-19 and Common Mental Health Symptoms in the Early Phase of the Pandemic: An Umbrella Review of the Evidence. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickens, C.M.; Popal, V.; Fecteau, V.; Amoroso, C.; Stoduto, G.; Rodak, T.; Li, L.Y.; Hartford, A.; Wells, S.; Elton-Marshall, T.; et al. The Mental Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic among Individuals with Depressive, Anxiety, and Stressor-Related Disorders: A Scoping Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čejauskas, A.; Dzinzinaitė, I.; Uža, T. Diagnosis and Management of Post-COVID-19 Syndrome in Primary Heath Care. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, S.; Matos, R.S. Understanding Emotional Fatigue: A Systematic Review of Causes, Consequences, and Coping Strategies. Enferm. Clin. (Engl. Ed.), 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, B.; McCombe, G.; Broughan, J.; Frawley, T.; Guerandel, A.; Gulati, G.; Kelly, B.D.; Osborne, B.; O’Connor, K.; Cullen, W. Enhancing GP Care of Mental Health Disorders Post-COVID-19: A Scoping Review of Interventions and Outcomes. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2023, 40, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farfán-Latorre, M.; Estrada-Araoz, E.G.; Lavilla-Condori, W.G.; Ulloa-Gallardo, N.J.; Calcina-Álvarez, D.A.; Meza-Orue, L.A.; Yancachajlla-Quispe, L.I.; Rengifo Ramírez, S.S. Mental Health in the Post-Pandemic Period: Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Peruvian University Students upon Return to Face-to-Face Classes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudan, N.M.; Ekiyanti, K.; Sania, R.A.; Athiyyah, A.F.; Sari, D.R.; Rochmanti, M. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among General Population Due to COVID-19 Pandemic in Several Countries: A Review Article. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2022, 13, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, F.F. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.; Honrado, A.; Leal, I. Contribuição Para o Estudo Da Adaptação Portuguesa Das Escalas de Ansiedade Depressão e Stress de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psycologica 2004, 36, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasoni, D.; Bai, F.; Castoldi, R.; Barbanotti, D.; Falcinella, C.; Mulè, G.; Mondatore, D.; Tavelli, A.; Vegni, E.; Marchetti, G.; et al. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms after Virological Clearance of COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study in Milan, Italy. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, M.C.; Barlow, P.B.; Comellas, A.P.; Garg, A. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms among Patients with Long COVID: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 274, 1879–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandifar, A.; Badrfam, R.; Yazdani, S.; Arzaghi, S.M.; Rahimi, F.; Ghasemi, S.; Khamisabadi, S.; Mohammadian Khonsari, N.; Qorbani, M. Prevalence and Severity of Depression, Anxiety, Stress and Perceived Stress in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2020, 19, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, L.; Higgins, J. Risk of Bias Tools—ROBINS-I V2 Tool. Available online: https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/robins-i-v2 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Walpita, Y.; Nurmatov, U. ROBINS-I: A Novel and Promising Tool for Risk of Bias Assessment of Nonrandomized Studies of Interventions. J. Coll. Community Physicians Sri Lanka 2020, 26, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsapara, A.; Plotas, P.; Giakoumis, A.; Kantanis, A.; Trimmi, N. The Underestimation of Depression in Primary Health Care in Greece during the Post-COVID-19 Pandemic: A Simulation Study. Environ. Soc. Psychol. 2025, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirz, M.; Nast, I.; Rausch, A.-K.; Beyer, S.; Hetzel, J.; Hofer, M. Evaluation of the Post-COVID Multidisciplinary Outpatient Clinic at the Pulmonary Division of the Cantonal Hospital Winterthur from the Patient’s Perspective: A Mixed-Methods Study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2024, 154, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peritogiannis, V.; Mantziou, A.; Vaitsis, N.; Aggelakou-Vaitsi, S.; Bakola, M.; Jelastopulu, E. Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Community-Dwelling Women in Rural Areas of Greece in the Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Era. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkayam, S.; Łojek, E.; Sękowski, M.; Żarnecka, D.; Egbert, A.; Wyszomirska, J.; Hansen, K.; Malinowska, E.; Cysique, L.; Marcopulos, B.; et al. Factors Associated with Prolonged COVID-Related PTSD-like Symptoms among Adults Diagnosed with Mild COVID-19 in Poland. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1358979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppner, J.; Lindelöf, A.; Iredahl, F.; Tevell, M.; Nilsson, S.; Thorsell, A.; Faresjö, Å.; Israelsson Larsen, H. Factors Affecting Self-Perceived Mental Health in the General Older Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrempft, S.; Pullen, N.; Baysson, H.; Zaballa, M.-E.; Lamour, J.; Lorthe, E.; Nehme, M.; Guessous, I.; Stringhini, S. Mental Health Trajectories among the General Population and Higher-Risk Groups Following the COVID-19 Pandemic in Switzerland, 2021–2023. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 359, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.D.; McQuaid, A.; Leeson, V.C.; Samuel, O.; Grant, J.; Imran Azeem, M.S.; Barnicot, K.; Crawford, M.J. The Association of Severe COVID Anxiety with Poor Social Functioning, Quality of Life, and Protective Behaviours among Adults in United Kingdom: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanftenberg, L.; Keppeler, S.; Heithorst, N.; Dreischulte, T.; Roos, M.; Sckopke, P.; Bühner, M.; Gensichen, J. Psychological Determinants of Vaccination Readiness against COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza of the Chronically Ill in Primary Care in Germany—A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, J.; Bundschuh, R.; Kaußner, Y.; Simmenroth, A. Lingering Symptoms in Non-Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19—A Prospective Survey Study of Symptom Expression and Effects on Mental Health in Germany. BMC Prim. Care 2025, 26, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, A.; Klompstra, L.; Cezón-Serrano, N.; Deka, P.; Arnal-Gómez, A.; Querol-Giner, F.; Marques-Sule, E. Psychological Health Among Older Adults During and After Quarantine: A Multi-Method Study. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2024, 46, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrnić Novaković, I.; Ajduković, D.; Bakić, H.; Borges, C.; Figueiredo-Braga, M.; Lotzin, A.; Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, X.; Lioupi, C.; Javakhishvili, J.D.; Tsiskarishvili, L.; et al. Shaped by the COVID-19 Pandemic: Psychological Responses from a Subjective Perspective–A Longitudinal Mixed-Methods Study across Five European Countries. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomou, I.; Nikolaou, F.; Michaelides, M.P.; Constantinidou, F. Long-Term Psychological Impact of the Pandemic COVID-19: Identification of High-Risk Groups and Assessment of Precautionary Measures Five Months after the First Wave of Restrictions Was Lifted. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesanti, S.; Goveas, D.; Bali, K.; Campbell, S. Exploring Factors Shaping Primary Health Care Readiness to Respond to Family Violence: Findings from a Rapid Evidence Assessment. J. Fam. Violence 2025, 40, 963–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Dalton-Locke, C.; Baker, J.; Hanlon, C.; Salisbury, T.T.; Fossey, M.; Newbigging, K.; Carr, S.E.; Hensel, J.; Carrà, G.; et al. Acute Psychiatric Care: Approaches to Increasing the Range of Services and Improving Access and Quality of Care. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkbride, J.B.; Anglin, D.M.; Colman, I.; Dykxhoorn, J.; Jones, P.B.; Patalay, P.; Pitman, A.; Soneson, E.; Steare, T.; Wright, T.; et al. The Social Determinants of Mental Health and Disorder: Evidence, Prevention and Recommendations. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, E.G.; Ijadi-Maghsoodi, R.; Shadravan, S.; Moore, E.; Mensah, M.O.; Docherty, M.; Aguilera Nunez, M.G.; Barcelo, N.; Goodsmith, N.; Halpin, L.E.; et al. Community Interventions to Promote Mental Health and Social Equity. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.; Marques, P.; Matos, R.S. Exploring Aromatherapy as a Complementary Approach in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2024, 27, 1247–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.; Matos, R.S. Effectiveness of Cognitive Interventions in Mitigating Mental Fatigue among Healthcare Professionals in Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Popul. Stud. 2024, 4276, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.; Heightman, M.; Allsopp, G. Learning from Long COVID: Integrated Care for Multiple Long-Term Conditions. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2023, 73, 196–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study No. Reference Year of Publication Country | Study Design and Setting | Sample Characteristics | Measurement Tools Used | Results of Assessment Tools | Associated Factors Identified | Main Findings and Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [21] 2025 Greece | -Cross-sectional study -Primary Health Care Centres in Western Greece | -212 participants -Mean age: 50.36 years (SD 6.20) -Age range: 40–60 years -Females: 125 (59.4%) | -PHQ-9 -FAST | -PHQ-9: 63.2% had depressive symptoms: -28.3% mild depression -18.4% moderate depression -16.5% severe depression -FAST: Low prevalence of alcohol problems; no significant association with depression | -Marital status (divorced, unmarried, widowed had higher depression). -History of hospitalization. -Presence of chronic physical illness. -Professional status (unemployed and retired showed higher depression). - Presence of children (those without children had higher depression). -Income and educational level showed trends but were less significant | There is a significant underdiagnosis of depression in primary health care during the post-COVID-19 era. Depression was prevalent among middle-aged adults (40–60 years), independent of gender and alcohol consumption. Important demographic and clinical variables influence depression risk. Findings emphasize the need for routine mental health screening in primary care using tools like PHQ-9, especially considering factors like family status, employment, and physical health |

| 2 [22] 2024 Switzerland | -Cross-sectional study. -Conducted in primary care settings (five general practices in the Canton of Vaud) -Data collected at three time points: ·t1: 0–7 days post-consultation t2: 4–8 weeks post-consultation t3: 4–6 months post-consultation | -50 patients -Female: 33 (66%) -Mean age: 47 years (IQR: 36–55) | -HADS -CSF -PCFS -PC-VAS -Study-specific questions regarding symptoms and reasons for consulting the post-COVID outpatient clinic | -Quantitative data indicated that most patients (96%) felt cared for throughout their consultations. -Qualitative interviews highlighted the medical staff’s attentiveness and the time dedicated to consultations, which made patients feel that their complaints were taken seriously and that they received appropriate information | -High emotional burden and fatigue early post-COVID; improvement associated with follow-up care and multidisciplinary support; long wait times noted as a concern | The outpatient clinic effectively addressed patients’ emotional and physical health over time, with most feeling well cared for. Interprofessional support was crucial, and fatigue and restrictions improved significantly by t3 |

| 3 [23] 2024 Greece | -Cross-sectional study conducted over two months -Location: Two primary health care sites in the rural region of Farsala, Central Greece -Conducted after the lifting of all COVID-19 restrictive measures | -129 women -27.9% classified as older adults -13.2% reported having a chronic physical disease | -DASS-21 | -DASS-21 (Depression): 17.1% of participants reported clinically relevant depressive symptoms. -DASS-21 (Anxiety): Over 40% of participants reported clinically relevant anxiety symptoms. -Symptoms of anxiety and depression were found to be interrelated. -Anxiety and depression symptoms were found to be interrelated | -Older Age: Associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression. -Primary Education: Linked to increased symptoms. -Living Alone: Significantly associated with anxiety (OR 123.5; 95% CI: 7.3–2098.8) and depression (OR 3.5; 95% CI: 1.3–9.8). -Unemployment: Associated with higher anxiety (OR 0.157; 95% CI: 0.06–0.41) and depression (OR 0.08; 95% CI: 0.01–0.62). -Chronic Physical Disease: Strongly linked to anxiety (OR 33.8; 95% CI: 4.3–264.7) and depression (OR 37.2; 95% CI: 10–138.1) | -A significant proportion of community-dwelling women in rural Greece exhibited symptoms of anxiety and depression in the post-COVID-19 era. -Certain sociodemographic factors, such as age, education level, living status, employment status, and chronic disease history, were associated with increased symptoms. -The study emphasizes the importance of screening for depression and anxiety symptoms in women attending rural primary care settings. -Using valid and reliable self-report instruments, such as the DASS-21, can aid in early identification and intervention |

| 4 [24] 2024 Poland | -Longitudinal cohort study assessing psychological outcomes in adults diagnosed with mild COVID-19. -Participants completed online self-report questionnaires at two time points: baseline (T1) and approximately four months later (T2) | -341 adults with confirmed mild COVID-19. -Female: 204 (59.8%) -Mean age: 42.89 (SD 13.89) | -PHQ-ADS -PC-PTSD-5 -Scale of Psychosocial Experience Related to COVID-19: Measured COVID-related stigma and social support. -Self-designed questionnaires: Evaluated the severity of COVID-related medical and neurocognitive symptoms | -Exploratory factor analysis identified five clusters of COVID-19 symptoms: flu-like, respiratory, cold, neurological, and neurocognitive. -Hierarchical logistic regression revealed that neurocognitive symptoms at T1 (e.g., impairments in smell and taste, information processing, memory, thinking, and verbal communication) were significant predictors of prolonged PTSD-like symptoms at T2. - Other symptom clusters (flu-like, respiratory, cold, neurological) did not significantly predict PTSD-like symptoms | -Neurocognitive symptoms during acute COVID-19: Strongly associated with prolonged PTSD-like symptoms. -Emotional symptoms during illness: The Presence of anxiety and depression at T1 contributed to PTSD-like symptoms at T2. -COVID-related stigma: Experiences of social stigma due to infection were linked to increased risk of prolonged PTSD-like symptoms. -Subjective perceptions of neurocognitive deficits: Individuals’ perceptions of their cognitive impairments played a role in the persistence of PTSD-like symptoms | The study concluded that among adults with mild COVID-19, neurocognitive symptoms during the acute phase are significant predictors of prolonged PTSD-like symptoms. Emotional distress and experiences of stigma further exacerbate this risk. The findings underscore the importance of comprehensive neuropsychological assessments and interventions for individuals recovering from COVID-19, even in cases of mild illness. Enhancing access to neuropsychological services is crucial for addressing the mental health needs of this population |

| 5 [25] 2024 Sweden | -Cross-sectional cohort study -Primary care settings | -260 participants -Female: 146 (56.2%) | -GDS-20 -HADS -PSS-10 | -Participants reporting mental health impacts due to the COVID-19 pandemic exhibited significantly higher levels of anxiety (p < 0.001), depression (p < 0.001), and stress (p = 0.026) compared to those not reporting such impacts | -Impaired social life -Changes in physical activity - Strained family relationships -Higher levels of anxiety -Being female | The study concluded that anxiety, family situation, social life, and changes in physical activity were the main factors influencing self-perceived mental health among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings suggest the need for further investigation into the long-term effects of social restrictions on the mental health of the older population |

| 6 [26] 2024 Switzerland | -Longitudinal cohort study | -5624 adults -Mean age: 51.5 (SD 13.2) -Female: 3456 (57.2%) | -GAD-2 -PHQ-2 -Loneliness Scale | -Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms: Declined during the pandemic wave (Feb–May 2021) and remained lower at follow-ups in 2022 and 2023 compared to the start of the wave. - Loneliness: Also declined over time, with the greatest decrease during the pandemic wave | -Higher-Risk Groups: Socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals, those with chronic conditions, and those living alone exhibited poorer mental health throughout the study period. - Demographics: Women and younger individuals showed faster improvements in mental health during the pandemic wave. - Loneliness: Trajectories of loneliness were closely associated with mental health trajectories throughout the study period | While mental health indicators improved relatively soon after the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, disparities persisted among higher-risk groups. The study underscores the need for continued mental health support for vulnerable populations beyond the pandemic period |

| 7 [27] 2023 United Kingdom | -Cross-sectional survey | -306 adults -Female: 246 (81.2%) -Mean age: 41 years (IQR 28–53) | -CAS -WSAS -EQ-5D-3L -PHQ-9 -GAD-7 -OCI-R -SHAI -SAPAS | -Social Functioning: 52.3% exhibited severe social or occupational dysfunction (WSAS score >20). -Quality of Life: 93.4% reported anxiety or depression; 10.4% rated their health state as worse than death (EQ-5D-3L index <0). -Protective Behaviours: High engagement in protective behaviours, including constant handwashing and avoiding leaving home | -Depressive Symptoms: Strongly correlated with functional impairment (β = 0.45; p < 0.001) and poor quality of life (r = -0.48; p < 0.001). -Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms: Associated with increased functional impairment (β = 0.13; p < 0.001). -Health Anxiety and Personality Disorder Traits: Linked to poorer quality of life. -Living Alone: Associated with worse social functioning and quality of life. -At-Risk Ethnic Group: Predictive of severe social impairment. -Having a Loved One Hospitalized by COVID-19: Associated with increased functional impairment | Severe COVID-19-related anxiety is associated with significant social and occupational dysfunction, diminished quality of life, and heightened engagement in protective behaviours. Comorbid mental health conditions, such as depression and obsessive-compulsive symptoms, exacerbate these outcomes. The study underscores the need for targeted mental health interventions for individuals experiencing severe COVID-19 anxiety |

| 8 [28] 2023 Germany | -Cross-sectional survey conducted between August and December 2022 across 13 general practices encompassing both urban and rural regions | -795 adults with at least one chronic physical illness (bronchial asthma, COPD, diabetes type 1 or 2, coronary artery disease, or breast cancer) | -5C Scale -PHQ-9 -OASIS -LSNS -PRA -PAM-13 | -Depression (PHQ-9): Higher depressive symptoms were significantly associated with lower confidence in COVID-19 vaccines (p = 0.010) and greater perceived constraints to vaccination (p = 0.041). -Anxiety (OASIS): No significant association with vaccination readiness for either COVID-19 or influenza vaccines. -Influenza Vaccination Readiness: No significant associations found with either depression or anxiety levels | -Depression: Negatively impacted confidence and increased perceived barriers to COVID-19 vaccination. - Anxiety: No significant influence on vaccination readiness. - Other Factors: Older age, male gender, and higher education levels were associated with increased vaccination readiness. A strong doctor-patient relationship has a positive influence on vaccination attitudes | Mental health, particularly depressive symptoms, plays a significant role in vaccination readiness among chronically ill patients, specifically concerning COVID-19 vaccines. Addressing mental health issues and strengthening the doctor-patient relationship are crucial strategies to enhance vaccination uptake in this population |

| 9 [29] 2023 Germany | -Prospective observational survey study. -Primary care and community setting. | -60 patients -Female: 36 (60%) -Mean age: 45.4 (SD 14.9) | -GAD-7 | -Persistent symptoms reported months after infection. -Depression and anxiety scores were significantly elevated in individuals with lingering symptoms | -Number and intensity of lingering physical symptoms were strongly associated with increased anxiety and depressive symptoms. -No significant associations with age or sex were reported | Lingering physical symptoms in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients were strongly associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety. Mental health assessment and follow-up in primary care are essential for this group |

| 10 [30] 2023 Spain | Multi-method study combining quantitative and qualitative approaches to assess psychological health among older adults during and after the first COVID-19 lockdown | -111 older adults. -Mean age: 71 years (SD 5 years). -Female: 84 (76%) | -GDS -Cantril Ladder of Life -PGIC -Open-ended questions: Explored personal experiences and perceived changes in depressive symptoms and well-being during quarantine | -Depressive Symptoms: 63% reported mild symptoms; 2% reported major depressive symptoms. -Changes During Lockdown: 47.7% reported changes in depressive symptoms; 37% felt better during lockdown, while 11% reported worsening symptoms post-lockdown. -Well-being: 60% reported a decline in well-being during quarantine | -Psychological Discomfort: Mood deflection, fear and worries, and boredom and inactivity were common themes. -Social Issues: Inability to go out and missing family members contributed to psychological distress | The study highlighted that a significant proportion of older adults experienced worsening depressive symptoms and decreased well-being during and after COVID-19 lockdowns. Psychological discomfort and social isolation were key contributing factors. The findings underscore the importance of evaluating mental health in primary care settings and providing appropriate referrals for older adults affected by pandemic-related restrictions |

| 11 [31] 2023 Austria, Croatia, Georgia, Greece, Portugal | -Longitudinal mixed-methods study with baseline assessment in summer/autumn 2020 (T1) and follow-up 12 months later (T2) | -1070 adults from the general population -Mean age: 42.9 (SD 13.5) -Female: 796 (74.4%) | -ADNM -PC-PTSD-5 -PHQ-2 -WHO-5 | -ADNM-8: Significant decrease in Greece (p = 0.007); increase in Georgia (p = 0.035); stable in other countries. -Depressive Symptoms (PHQ-2): Significant decrease in Greece (p = 0.001); slight decrease in Croatia (p = 0.032); stable elsewhere. -Well-Being (WHO-5): No significant change across countries. -PC-PTSD-5: Slight decrease in total sample (p = 0.057) | -Country-Specific Differences: Variations in mental health outcomes across countries. -Time point Variations: Changes in themes such as work/finances (T1) and vaccination issues (T2). -Individual Characteristics: Personal experiences and circumstances influenced psychological responses | Psychological responses to the COVID-19 pandemic varied over time and across countries, influenced by contextual factors and individual circumstances. Resource-oriented interventions focusing on psychological flexibility may promote resilience and mental health during global crises |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diogo Gonçalves, S.; Santos, A.L.; Ramos, C.; Valente, F.; Jesus, L.; Pereira Alexandre, J.; Chyczij, F. Mental Health in Europe After COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Adult Primary Health Care Users. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030109

Diogo Gonçalves S, Santos AL, Ramos C, Valente F, Jesus L, Pereira Alexandre J, Chyczij F. Mental Health in Europe After COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Adult Primary Health Care Users. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(3):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030109

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiogo Gonçalves, Sara, Ana Luísa Santos, Clara Ramos, Fábio Valente, Lisete Jesus, José Pereira Alexandre, and Fabiana Chyczij. 2025. "Mental Health in Europe After COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Adult Primary Health Care Users" Psychiatry International 6, no. 3: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030109

APA StyleDiogo Gonçalves, S., Santos, A. L., Ramos, C., Valente, F., Jesus, L., Pereira Alexandre, J., & Chyczij, F. (2025). Mental Health in Europe After COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Adult Primary Health Care Users. Psychiatry International, 6(3), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030109