Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the mediating effects of depression and interpersonal contact on the association between cognitive function and activities of daily living (ADL) in older adult patients with dementia. This descriptive cross-sectional study used the 2020 Korea Elderly Survey and included 189 older adults aged 65 years who were diagnosed with dementia by a physician. The analysis involved descriptive statistics and correlation analysis with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0, and the dual mediation effect was analyzed with PROCESS Macro for SPSS version 3.5 Model 6. Cognitive function was negatively related to both ADL and depression but positively correlated with interpersonal contact. ADL exhibited positive and negative correlations with depression and interpersonal contact, respectively. Cognitive function significantly affected ADL and depression. Cognitive function significantly affected interpersonal contact, but depression was not significant. Finally, cognitive function exhibited a significant effect on ADL, but depression and interpersonal contact were not significant. Cognitive function showed the greatest effect on ADL in older adults diagnosed with dementia. Therefore, a program to prevent cognitive decline in older adults with dementia needs to be developed. Additionally, further studies are warranted to investigate the factors that affect the association between cognitive function and ADL in older adults with dementia.

1. Introduction

Depression is a crucial risk factor for dementia. Empirical studies reveal that depression accounts for 8.6% of newly diagnosed dementia cases and 10.8% of Alzheimer’s disease cases [1], emphasizing its significant correlation. Furthermore, individuals with a depression history demonstrate a 1.85-fold increased relative risk of developing any form of dementia [2]. Several studies have posited depression as either a precursor or a consequence of dementia, but recent meta-analyses have yet to definitively ascertain its causal or resultant nature [3]. However, other research results indicate that individuals diagnosed with severe depression present markedly higher relative risks for dementia, demonstrating variability in the association between depression and dementia contingent upon depression severity [4]. Thus, the association between depression and dementia appears robust, but the underlying mechanisms and causal pathways remain under investigation. Factors such as the severity, duration, and onset timing of depression concerning its effect on dementia risk need to be considered. Moreover, understanding how depression severely impairs activities of daily living (ADL) in individuals with dementia should be integral to devising comprehensive management strategies.

Recent global research has shown that the direct impact of depression on the onset and progression of dementia is universally observed across cultural contexts. According to previous studies [4], individuals with depression have a significantly higher risk of developing dementia than those without depression, and this risk increases with the severity of depression. While these studies suggest that depression is a significant risk factor for dementia, the specific mechanisms by which depression acts as a risk factor or mediating variable in the relationship between cognitive function and activities of daily living (ADL) have not been clearly elucidated. Previous studies [5] have found that social isolation is associated with memory decline in women, but not significantly in men, highlighting the need for replication and further research; however, empirical evidence on whether interpersonal contact mediates the relationship between cognitive function and ADL is lacking. Studies analyzing the role of these mediating variables among older Korean adults are particularly scarce. Within this global research context, simultaneously identifying the uniqueness and universality of Korean data will contribute to the generalizability and development of country-specific intervention programs in the future.

Individuals with dementia frequently experience diminished interpersonal relationships and communication capacities, causing social isolation, despite being inherently social beings whose dignity warrants preservation. This isolation precipitates depression and exerts deleterious effects on daily functioning [6], perpetuating a vicious cycle that exacerbates the individual’s condition. Fostering interpersonal contact is crucial to disrupting this cycle and improving ADL abilities among cognitively impaired older adults with dementia. Previous research has revealed that sustained interpersonal relationships with family or friends mitigate cognitive decline among individuals with dementia [7], which affirms the significance of social interaction. Communication and interpersonal associations are pivotal in sustaining social interactions among older adults with dementia.

These studies emphasize that human relationships, communication skills, and social interactions exert profound effects on cognitive function and ADL in individuals with dementia. Depression frequently co-occurs with dementia in older adults and negatively affects both cognitive function and ADL by diminishing motivation for routine activities. Consequently, depression may be a critical mediating variable in the association between cognition and ADL [8]. Previous studies have investigated the role of various mediating variables in the relationship between cognitive function and activities of daily living (ADL) and reported both significant and non-significant mediation effects. In contrast to the present study, which focused on individuals with dementia, earlier research targeting older adults [9] found that social interaction and lifestyle mediated the relationship between cognitive function and ADL disability, suggesting that these factors have significant mediating effects. However, individuals with dementia exhibit more complex neuropsychological characteristics than the general older adult population, which can manifest as cognitive decline and behavioral symptoms. This distinction underscores the need to consider these unique characteristics in this study. This study aims to provide empirical evidence that can contribute to the development of intervention strategies to improve the quality of life of individuals with dementia. Another study [10] highlighted the importance of social participation and lifestyle in reducing the risk of dementia and cognitive decline, although it did not conduct a detailed analysis of the mediation effects. This highlights the complexity of the factors influencing cognitive function and ADL in different populations, emphasizing the necessity for targeted research, such as the present study, to explore these dynamics in the context of dementia.

By examining the dual mediating effects of these factors, we aimed to provide insights into how cognitive decline affects ADL through psychological and social pathways. This approach is crucial for developing comprehensive care strategies that address both the psychological and social needs of individuals with dementia and ultimately enhance their quality of life. In other words, depression commonly accompanies older adults with dementia, negatively affecting cognitive function and ADL abilities by reducing motivation for routine activities. Thus, the precise mediating effects of depression and interpersonal contact on cognition–ADL ability relationships require further investigation. Elucidating how alleviating depression and promoting social interactions contribute to effective policy development and clinical intervention strategies will provide invaluable foundational data for improving the quality of life of individuals with dementia while mitigating societal costs.

Therefore, this study aims to determine the mediating roles of depression and interpersonal contact within the association between cognition and ADL in older adults with dementia, thereby contributing to developing efficacious management and intervention strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is descriptive research that utilizes the 2020 Elderly Survey data as a secondary analysis study to determine the mediating effects of depression and interpersonal contact on the association between the cognitive function and ADL of older adults with dementia.

2.2. Participants

This study used the 2020 Elderly Survey data. The Elderly Survey is a statutory survey according to Article 5 of the Elderly Welfare Act and is conducted to improve the quality of life of older adults by determining their living conditions, characteristics, and needs. In 2020, a survey was conducted on older adults aged ≥65 in 969 survey districts based on the designed sampling method, and 10,097 individuals completed the survey.

Of 9920 people who responded directly, this study excluded 177 people who responded through a proxy and targeted 189 people who were diagnosed with dementia by a doctor.

2.3. Study Variables

General characteristics included age (65–74 years or ≥75 years), gender (male or female), educational level (elementary school graduate or less or middle school graduate or higher), household type (living alone or living with a spouse), economic activity, receiving help with daily life (yes or no), average daily TV watching or radio listening time (dichotomized based on 5 h corresponding to the 50th percentile [median], <5 h, or ≥5 h), and suicidal thoughts (yes or no).

We measured cognitive function using the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for Dementia Screening (MMSE-DS) developed by Kim et al. [11] through standardization of the MMSE developed by Folstein et al. [12]. The MMSE-DS involves 19 items, consisting of orientation, memory, concentration, language ability, executive ability, figure simulation, judgment, and problem-solving ability, and the score ranges from 0 to 30 points. This study used the MMSE-DS total score from the Survey on the Status of Older Adults. A higher score indicates better cognitive function. Cronbach’s ⍺ was 0.83 during the Korean version development and 0.90 in this study.

ADL was measured with the Korean version of the Weighting items of Korean Activities of Daily Living (K-ADL) developed by Won et al. [13]. K-ADL includes seven items: bathing, dressing, toilet use, transferring, urinary and bowel control, eating, and washing. It is measured on a 3-point scale (1, 2, and 3 s indicating complete independence, partial assistance, and complete assistance, respectively). The score ranges from 7 to 21 points, and a higher score indicates a lower ADL. Cronbach’s α was 0.98 in the study by Park et al. [14] and 0.95 in this study.

Depression was measured with the Korean version of the Short Form of Geriatric Depression Scale (SGDS-K) developed by Yesavage et al. [15] and standardized by Kee [16]. It includes 15 items, each answering “yes” or “no” on a dichotomous scale, with “yes” 1 point and “no” 0 points. Five items with reversed content were reverse-coded, and the total score ranges from 0 to 15 points, with a higher score indicating more severe depression. Cronbach’s α was 0.88 during the Korean version development [16] and 0.85 in this study.

Interpersonal contact is the frequency of contact with people around you in the past year. The scope of people around you was categorized into three types: non-living children, relatives including siblings, and friends, neighbors, and acquaintances, which reflected the questions on the older adults status survey [17]. The question that measures the contact frequency was “How often have you contacted (by phone, text message, e-mail, letter, etc.) all of your children (including your child’s spouse)/relatives, including siblings/friends, neighbors, and acquaintances who live away from you in the past year?”. It was recategorized into 1–6 points for almost no contact, 1–2 times a year, 1–2 times every 3 months, 1–2 times a month, 1–3 times a week, and ≥4 times a week to almost every day, respectively. A higher score indicates more contact.

2.4. Data Collection

A total of 169 interviewers conducted the 2020 Korea Elderly Survey from 14 September to 20 November 2020, through one-on-one interviews. The 2020 Korea Elderly Survey received approval for statistical changes from Statistics Korea regarding the sample design and survey content (Approval No. 117071) and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (IRB of the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, Notice of Review Results No. 2020-36).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

This study data analysis was conducted with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 25.0 program, and the significance level was set at 0.05. Descriptive statistics were utilized to identify the general characteristics and study variables. The correlations between cognitive function, ADL, depression, and interpersonal contact were analyzed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Model 6 of Hayes’s PROCESS Macro for SPSS version 3.5 was applied to determine the mediating effects of depression and interpersonal contact in the association between cognitive function and ADL [18]. Additionally, the bootstrapping method was utilized to verify the significance of the mediating effect to confirm the indirect effect.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics and Degree of Study Variables

The average age of the participants of this study was 81.12 years, with 16.9% aged 65–74 years and 83.1% aged ≥75 years. The female population was more prevalent, at 67.7%, and the majority had graduated from elementary school, at 74.1%. The family structure was 49.6% of the older adults living alone, 61.4% living with a spouse, and only 14.3% were economically active. Additionally, 33.3% of the participants had visual impairment and 65% of the older adults had hearing impairment. Moreover, 6.9% of the participants responded that they demonstrate self-thinking. The cognitive function of the participants in this study was 13.17 ± 9.61 points, and the ADL was 9.10 ± 3.68 points. Depression was 3.41 ± 3.13 points, and interpersonal contact was 3.18 ± 1.12 points (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics and degree of study variables (N = 189).

3.2. Correlation Between the Participants’ Cognitive Function, ADL, Depression, and Interpersonal Contact

A negative correlation was observed between cognitive function and ADL (r = −0.44, p < 0.001) and depression (r = −0.38, p < 0.001), and a positive correlation was observed between interpersonal contact (r = 0.26, p = 0.017). ADL exhibited a positive correlation with depression (r = 0.23, p = 0.005) and a negative correlation with interpersonal contact (r = −0.24, p = 0.015) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations among research variables (N = 189).

3.3. Mediating Effects of Depression and Interpersonal Contact on the Association Between the Participants’ Cognitive Function and ADL

Model 6 of PROCESS Macro for SPSS version 3.5 was applied to analyze the mediating effects of depression and interpersonal contact in the association between the participants’ cognitive function and ADL.

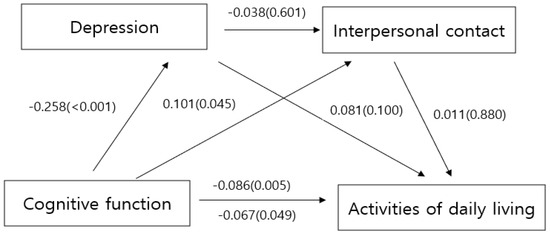

Table 3 and Figure 1 show that each model was partially significant. In step 1, cognitive function significantly affected ADL (B = −0.086, p = 0.005), and in step 2, cognitive function significantly affected depression (B = −0.258, p = 0.001). In step 3, cognitive function (B = 0.101, p = 0.045) significantly affected interpersonal contact, but depression (B = −0.038, p = 0.601) was not significant. In step 4, cognitive function (B = −0.067, p = 0.049) exhibited a significant effect on ADL, but depression (B = 0.081, p = 0.100) and interpersonal contact (B = 0.011, p = 0.880) were not significant.

Table 3.

Mediating effect of depression and interpersonal contact on the relationship between cognitive function and ADL in older adults (N = 189).

Figure 1.

Mediating effect of variables.

The difference in the effect values for the three paths, namely the paths where only the first, the second, and both the first and second parameters were input, was compared to identify the significance and magnitude of the effects of the dual mediation effect. The bootstrapping method was utilized to verify the significance of the mediation effect, and the sample was re-extracted 10,000 times. Significance was confirmed with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Table 4 presents that the indirect effects of the mediating variables, depression and interpersonal contact, were not significant in the path from cognitive function to ADL through depression (B = −0.021, 95% CI: −0.058–0.006), the path from cognitive function to ADL through interpersonal contact (B = 0.001, 95% CI: −0.015–0.015), and the path from cognitive function to ADL through depression and interpersonal contact (B = 0.001, 95% CI: −0.001–0.004), as all 95% CIs included 0. The differences in the mediating effects of the three paths were not significant.

Table 4.

Validation of mediating effect (bootstrapping) (N = 189).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the dual mediating effects of depression and interpersonal contact on the association between cognitive function and ADL in older adults with dementia. The cognitive function score of the participants in this study was 13.17, which was significantly lower than the average score of 23.73 reported by Kim [19], who analyzed data from the 2020 Elderly Survey, and the 23.96 points reported by Kang [20] in an analysis with the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging. Further, it was lower than the approximately 19-point score observed by Ahn et al. [21] in a study of older adult individuals with mild dementia. The ADL score of the participants was 9.10, which was slightly lower than the 10.41–10.61 points reported by Kim et al. [22] in a study that focused on older adult individuals in long-term care grades 4–5 receiving home care. This indicates that the participants in this study indicated similar or somewhat greater independence in ADL compared with older adults in the lower care grades. The depression score of the participants was 3.41 out of 15, which was lower than the 7.88 out of 30 points reported by Cho [23], who investigated individuals with mild cognitive impairment using the Aging Panel Survey data. Interpersonal contact was rated at 3.18 out of 6 points. Compared to the results of Yu et al. [24], who revealed a frequency of interpersonal contact ranging from 3.25 to 3.28 out of 4 points among young adults living alone, the current study reported a notably lower interpersonal contact frequency among older adults with dementia.

This study suggested that cognitive function influences the activities of daily living (ADL). Decline in ADL is a common issue among older adults with cognitive impairments, such as mild cognitive impairment or dementia, and numerous studies have aimed to address this challenge [25,26,27]. However, the specific mechanisms by which cognitive function affects ADL in older adults without pathological conditions remain unclear. A meta-analysis examining the link between cognitive function and ADL found that instrumental activities of daily living are associated with executive function, regardless of cognitive status, whereas basic ADLs are linked to overall cognitive performance and long-term verbal memory [28]. Therefore, to support independent living, which is an essential aspect of healthy aging, ongoing efforts are needed to preserve cognitive function in older adults. In particular, the early detection and prevention of cognitive decline should be prioritized to reduce the risk of pathological conditions.

This study found a negative correlation between cognitive function, depression, and activities of daily living (ADL). Cognitive function significantly impacted both depression and ADL; however, depression did not mediate the relationship between cognitive function and ADL. Specifically, while cognitive decline was associated with increased depression, depression did not directly contribute to a decline in ADL. These findings contrast with those of previous research that reported a significant association between depression and ADL [29,30], as well as a meta-analysis suggesting that depression influences ADL [31]. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that participants in the present study had relatively low average depression scores. This finding suggests that the direct impact of cognitive decline on ADL may be stronger than the indirect influence of depression in populations with low levels of depression. Another possibility is that the study may not have adequately controlled for the participants’ general characteristics or other confounding factors that could affect ADL. To gain a clearer understanding of the relationship between depression and ADL, future research should include older adults with a wider range of depression scores. Additionally, such studies should account for the general characteristics and potential confounding variables that may influence ADL outcomes.

Cognitive function in older adults was positively associated with and influenced by interpersonal contact. However, this study did not find evidence that depression mediated the relationship between cognitive function and interpersonal contact. This study narrowly defined interpersonal contact, focusing only on interactions with family, friends, and acquaintances. Previous research has shown that Internet use among older adults can enhance social interaction and reduce the risk of depression, suggesting that the emotional benefits of interpersonal relationships may extend beyond close personal ties [32]. Another study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that the frequency of contact with family, friends, and acquaintances did not significantly impact the levels of depression, indicating the need to broaden the scope of meaningful interpersonal contact in future research [33]. Moreover, a separate study comparing individuals with and without depressive symptoms found that, while interpersonal relationship scores were linked to the onset of depression in those with depressive symptoms, no such relationship was observed in those without symptoms [34]. This implies that the lack of a mediating effect in the current study may be due to a generally low level of depression among the participants.

Future studies should therefore consider a wider range of interpersonal interactions and include older adult individuals with varying degrees of depression to better understand how interpersonal contact influences the relationship between cognitive function and depression. In conclusion, the dual mediation effect was not significant for the pathway where cognitive function in older adults with dementia reduces depression, thereby decreasing interpersonal contact and subsequently affecting their ability to perform ADL. However, this study is noteworthy as it investigates how cognitive function in older adults with dementia affects depression, interpersonal contact, and ADL, as well as the interconnected pathways among these factors. Notably, research investigating the effect of interpersonal contact on older adults with dementia is scarce, as are studies addressing the roles of depression and interpersonal contact in the association between cognitive function and ADL. Furthermore, recognizing the difficulties of conducting direct surveys with older adults with dementia, this study leveraged data from the Survey on the Status of Older Adults to provide meaningful information. This study demonstrated several limitations. First, cognitive function was evaluated with the MMSE. The MMSE is a validated screening tool, but its results may vary according to education level, and it has been criticized for lacking sufficient items on executive function [35]. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, which compensates for these shortcomings, should be considered to address these limitations in future studies on cognitive function in older adults. Second, comprehensive tools for assessing interpersonal contact are lacking. In this study, the evaluation of interpersonal interactions among older adults was limited to frequency, without distinguishing between their roles as recipients or senders. Previous studies have similarly utilized a single Likert scale question to evaluate the contact frequency. Future research should develop tools that differentiate and separately measure interpersonal contact reception and transmission. Finally, the depression scores of the participants in this study were notably low compared to the general older adult population. Therefore, future studies are warranted to target older adults with higher depressive symptom levels to better understand the association between depression and the variables studied.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated how depression and interpersonal contact affect the association between cognitive function and ADL in patients with dementia using data from the 2020 Korea Elderly Survey. The results indicated that cognitive function had a significant effect on ADL; however, neither depression nor interpersonal contact mediated the association between cognition and ADL. In particular, depression and interpersonal contact did not appear to contribute to the effect of cognitive function in reducing ADL in patients with dementia. This research is crucial because it provides foundational data on the factors that affect ADL in patients with dementia, demonstrating that cognitive function directly reduces ADL and that depression and interpersonal contact do not improve ADL outcomes. Based on the results of this study, the following suggestions are made: First, there is a need for improved tools to assess cognitive function in older adults as well as to develop comprehensive measures to evaluate their interpersonal interactions. Second, in follow-up studies on cognitive function, interpersonal contact, and depression among older adults, it is crucial to select participants with a broader range of depression levels to yield more meaningful results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.K., M.K. and K.S.; data curation, M.K.; methodology, S.A.K., M.K. and K.S.; software, S.A.K. and K.S.; supervision, M.K.; visualization, K.S.; writing—original draft, S.A.K. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (IRB No: 2020-36).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because of privacy concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Santabarbara, J.; Sevil-Perez, A.; Olaya, B.; Gracia-Garcia, P.; Lopez-Anton, R. Clinically relevant late-life depression as risk factor of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 68, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández Fernández, R.; Martín, J.I.; Antón, M.A.M. Depression as a risk factor for dementia: A meta-analysis. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 36, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiels, W.; Baeken, C.; Engelborghs, S. Depressive symptoms in the elderly—An early symptom of dementia? A systematic review. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-García, P.; De-La-Cámara, C.; Santabárbara, J.; Lopez-Anton, R.; Quintanilla, M.A.; Ventura, T.; Marcos, G.; Campayo, A.; Saz, P.; Lyketsos, C.; et al. Depression and incident Alzheimer disease: The impact of disease severity. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Luo, F.; Gao, N.; Yu, B. Social isolation and cognitive decline among older adults with depressive symptoms: Prospective findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 95, 104390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharani, A.; Zaidi, S.N.Z.; Jury, F.; Vatter, S.; Hill, D.; Leroi, I. The long-term impact of loneliness and social isolation on depression and anxiety in memory clinic attendees and their care partners: A longitudinal actor-partner interdependence model. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 8, e12235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, A.R. Social connectedness and cognitive decline. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e723–e724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, D.; Dong, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Han, Y. Bidirectional relationship between depression and activities of daily living and longitudinal mediation of cognitive function in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1513373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, C. Social interaction, lifestyle, and depressive status: Mediators in the longitudinal relationship between cognitive function and instrumental activities of daily living disability among older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratiglioni, L.; Paillard-Borg, S.; Winblad, B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004, 3, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Kim, T.H.; Jhoo, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.L.; Ryu, S.H.; Moon, S.W.; Choo, I.H.; Lee, D.W.; Yoon, J.C.; et al. A normative study of the Mini-Mental State Examination for Dementia Screening (MMSE-DS) and its short form (SMMSE-DS) in the Korean elderly. J. Korean Geriatr. Psythiatry 2010, 14, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, C.W.; Rho, Y.G.; SunWoo, D.; Lee, Y.S. The validity and reliability of Korean Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL) scale. J. Korean Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 6, 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Park, B.S. Testing reliability and measurement invariance of K-ADL. Health Soc. Welfare Rev. 2017, 37, 98–124. [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1983, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, B.S. Preliminary study for the standardization of geriatric depression scale short form-Korean version. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 1996, 35, 298–307. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C.W.; Choi, H.J. Senior’ Use of Text Messages and SNS and Contact with Informal Social Network Members. J. Digit. Converg. 2021, 19, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New Yor, NY, USA, 2013; 692p. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H. Factors influencing cognitive impairment in old adults with multimorbidity: Using data from the 2020 National Survey of Older Koreans. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2024, 25, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. Association between depression and cognitive function among older adults: The moderating role of social participation. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2024, 24, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ah, N.Y.; Ju, Y.S.; Lee, G.H.; Kim, K.J. Changes of body composition, physical fitness, and cognitive function after 16-week regular exercise training in elder women with dementia. J. Coach. Dev. 2019, 21, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.M.; Song, M.Y.; Yang, J.S.; Na, H.M. The effects of AI robot integrated management program on cognitive function, daily life activity, and depression of the elderly at home. J. Digit. Converg. 2022, 20, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M. Risk factors for depressive symptoms among older adults with mild cognitive impairment: And analysis of data from the eighth Korean Longitudinal study of aging 2020. J. Korean Acad. Fundam. Nurs. 2023, 30, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.H.; Yang, J.B.; Kim, J.Y. The impact of social isolation on depression among young single-person households: Focusing on the moderating effects of the frequency of contact with family, friends, and neighbors. Korean Soc. Wellness 2024, 19, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Li, W. Physical activity improves cognition and activities of daily living in adults with Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steichele, K.; Keefer, A.; Dietzel, N.; Graessel, E.; Prokosch, H.U.; Kolominsky-Rabas, P.L. The effects of exercise programs on cognition, activities of daily living, and neuropsychiatric symptoms in community-dwelling people with dementia—A systematic review. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, C.; Park, J.H. Ecological effects of VR-based cognitive training on ADL and IADL in MCI and AD patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, S.; Maggi, G.; Ilardi, C.R.; Cavallo, N.D.; Torchia, V.; Pilgrom, M.A.; Cropano, M.; Roldán-Tapia, M.D.; Santangelo, G. The relation between cognitive functioning and activities of daily living in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: A meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 2427–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Du, Y.; Li, X.; Ping, W.; Chang, Y. Physical function, ADL, and depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly: Evidence from the CHARLS. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1017689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Deng, H.; Chen, J.; Ding, D. Depressive symptoms and ADL/IADL disabilities among older adults from low-income families in Dalian, Liaoning. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 17, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.L.; Gignac, G.E.; Watson, P.A.; Brosnan, N.; Becerra, R.; Pestell, C.; Weinborn, M. Apathy and depression as predictors of activities of daily living following stroke and traumatic brain injuries in adults: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2022, 32, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Xie, Y.; Hu, Y. Internet use and depression among Chinese older adults: The mediating effect of interpersonal relationship. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Yang, M. The mediating effect of frequency of interpersonal contact on the association between stress and depression in pandemic. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2022, 23, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Qian, Y.; Sun, J.; Mu, F.; Jiang, F.; Xu, R.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Shu, J.; et al. Interpersonal relationship and the risk of major depressive disorder: Findings from a 1-year Chinese freshmen follow-up study. Preprint 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.H. Neuropsychological assessment of dementia and cognitive disorders. J. Korean Neuropsychiatry Assoc. 2018, 57, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).