1. Introduction

Divorce is a complex life transition that often disrupts emotional stability, economic security, and social integration. Across cultural and socio-economic contexts, numerous studies have shown that divorced women tend to experience greater financial hardship, psychological distress, and social isolation than their male counterparts [

1,

2]. The impacts of divorce, however, vary significantly depending on legal systems, family structures, and societal expectations [

3,

4,

5].

In conservative societies, such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE), divorced women often face heightened consequences due to deeply rooted cultural norms regarding gender roles, family responsibilities, and social status. These consequences can adversely affect their well-being, access to resources, and overall quality of life [

6]. Despite these realities, there remains a scarcity of empirical research in the Middle East—particularly in the Gulf region—that systematically examines the economic, emotional, and social challenges faced by divorced women.

Prior research identifies several key areas of concern in post-divorce life. Financial instability is frequently reported due to interrupted career paths, caregiving burdens, and limited access to income or assets [

3,

7]. Emotional distress is also common, with divorced women reporting symptoms such as anxiety, poor sleep, and social withdrawal [

8,

9]. Co-parenting stress has emerged as another critical issue, particularly in contexts marked by custody disputes or imbalanced parental roles [

10,

11,

12]. Additionally, difficulties in forming new social or romantic relationships persist, often exacerbated by social stigma in more traditional cultures [

13].

Against this backdrop, the present study seeks to explore the multi-dimensional realities of divorced women in Abu Dhabi. It draws attention to under-researched dynamics in the Gulf and contributes to a broader understanding of gender, family structure, and post-divorce well-being in conservative societies. By focusing on prominent themes in the global divorce literature, the study aims to inform social policy and support systems in ways that are culturally relevant and evidence based.

2. Literature Review

Divorce is a profound life transition with significant implications for economic stability, mental well-being, and social relationships. Research has consistently shown that women face greater economic and social hardships post-divorce, particularly in societies with strong cultural expectations regarding marriage and family structure [

1,

2,

14]. In the UAE, recent studies highlight the complex interplay of financial, emotional, and familial factors influencing divorced women’s well-being [

6,

15,

16]. This review synthesizes the existing literature through the lens of the key challenges identified in the Abu Dhabi study: financial insecurity, emotional distress, co-parenting struggles, and difficulty forming new relationships.

2.1. Financial Consequences of Divorce

One of the most widely documented impacts of divorce is economic instability, particularly for women [

3,

7]. Women generally experience a steeper decline in income and financial security following marital dissolution due to reduced household income, limited workforce participation, and caregiving responsibilities [

2,

17].

In high-income societies, financial hardship following divorce may be mitigated by access to social assistance programs and more equitable labor policies. However, women in Gulf countries often face unique challenges, including limited access to welfare systems, restricted labor market opportunities, and constraints tied to legal residency status. For example, some found that divorced women in Saudi Arabia frequently reported financial dependence, restricted financial autonomy, and difficulty securing stable employment due to cultural and institutional barriers [

18]. These patterns suggest that in similar regional contexts, financial insecurity may be shaped not only by individual circumstances but also by broader socio-political and legal frameworks that limit women’s post-divorce economic recovery.

2.2. Emotional Well-Being and Mental Health Post-Divorce

Divorce is a known psychological stressor, often linked to increased depression, anxiety, and decreased life satisfaction [

8,

19]. Studies indicate that women tend to experience greater emotional distress than men, largely due to social stigma, loss of economic security, and caregiving burdens [

9,

13].

The findings from the Abu Dhabi study reinforced these concerns, showing that divorced women facing emotional distress reported lower life satisfaction, poorer sleep quality, and higher digital reliance. The increase in online engagement among these women suggests that social isolation and digital coping strategies play a significant role in their post-divorce experience. Additionally, older divorced women reported greater difficulty forming new relationships, which may contribute to prolonged emotional distress and reduced trust in social networks.

2.3. Co-Parenting Challenges and Child Well-Being

A substantial body of research suggests that co-parenting stress is a major determinant of post-divorce well-being, particularly for women with primary custody of children [

10,

11,

20]. The Abu Dhabi study confirmed that middle-aged women (35–49) reported the highest levels of co-parenting stress, reflecting the challenges of balancing work, childcare, and legal responsibilities.

Studies have also found that the psychological well-being of divorced mothers is strongly correlated with their children’s adjustment outcomes [

21,

22]. In this context, divorced Emirati women reported significantly higher co-parenting stress than non-Emirati women, which may be linked to stronger cultural and familial expectations regarding motherhood. These findings suggest that targeted co-parenting programs and legal reforms could alleviate some of these burdens.

2.4. Social Reintegration and the Challenge of New Relationships

Social reintegration post-divorce remains a significant challenge for many women, especially in conservative societies where divorce carries stigma [

23]. Research has shown that women face greater barriers in forming new relationships due to social norms, self-esteem issues, and economic dependency [

24,

25,

26].

The Abu Dhabi study highlighted that difficulty in starting a new relationship was particularly pronounced for older divorcees, suggesting that age, financial independence, and social perceptions significantly influence post-divorce dating opportunities. Additionally, the study found increased religious engagement among women facing social stigma and emotional distress, possibly as a coping mechanism. Similar findings in Middle Eastern contexts suggest that religion plays a critical role in post-divorce identity reconstruction [

13,

27,

28].

In neighboring Gulf societies, the impact of stigma and lack of institutional support is similarly noted. A study in an exploratory study on divorced women in Saudi Arabia found that cultural constraints and the absence of rehabilitation programs significantly hindered women’s social reintegration and emotional recovery [

18].

2.5. Divorce and Well-Being in the Abu Dhabi Context

Existing research on well-being in Abu Dhabi has shown that financial stability, mental health, and social trust are key determinants of overall quality of life [

29]. These studies reinforce the results of this research, which demonstrated that financial pressures, emotional distress, and social isolation significantly lower life satisfaction among divorced women.

Age plays a crucial role in post-divorce adaptation. Younger divorcees (20–34) often exhibit greater resilience and social reintegration capacity, as they are more likely to re-enter the workforce or form new relationships [

1,

17]. In contrast, older divorced individuals (50+) experience heightened financial strain and social isolation, particularly if they were financially dependent on their spouses before the divorce [

28,

30]. Findings from Abu Dhabi reinforce this pattern, as financial insecurity and relationship difficulties were more pronounced among older divorced women.

Education serves as a key protective factor. Higher educational attainment is associated with better financial independence, stronger coping mechanisms, and increased life satisfaction post-divorce [

3,

4]. The Abu Dhabi study found that women without a college degree were significantly more affected by financial pressures and co-parenting difficulties.

Parental status is another important factor. Women with multiple children tend to report higher stress levels, financial burdens, and more difficulty reintegrating socially [

19,

31]. This was reflected in Abu Dhabi, where women with five or more children reported the lowest life satisfaction scores, particularly when experiencing financial hardship.

2.6. Theoretical Framework

This study is grounded in the Stress Process Model [

32], which conceptualizes life transitions, such as divorce, as primary stressors that can lead to secondary stressors (e.g., financial instability, co-parenting difficulties) that affect mental health and life satisfaction. However, to fully understand the Abu Dhabi context, this model benefits from integration with intersectionality theory, which emphasizes how overlapping systems of disadvantage—such as gender, nationality, education level, and caregiving status—compound the vulnerability of divorced women [

33]. This dual-theoretical lens allows for a more nuanced understanding of how post-divorce outcomes are shaped by both structural and cultural forces.

3. Methods and Analysis

3.1. Survey Instrument and Items

The study is based on data from the 5th Cycle Quality of Life Survey in Abu Dhabi, a comprehensive survey conducted to assess well-being indicators across multiple domains. The dataset includes responses from divorced women residing in Abu Dhabi, providing insights into their economic, social, and emotional distress post-divorce. The survey employs a structured questionnaire covering key well-being determinants, including the following:

Life satisfaction (0–10 scale, where 0 = not at all satisfied, 10 = completely satisfied).

Self-reported happiness (0–10 scale, where 0 = not at all happy, 10 = very happy).

Subjective health (1–5 scale, where 1 = poor, 5 = excellent).

Financial security (composite of three items: ability to pay for necessary expenses, satisfaction with household income, and income comparisons with other families). All are rated on a 1–5 scale. The computed reliability Alpha is 0.8681.

Mental health and emotional well-being (composite score derived from indicators such as stress levels, sleep quality, and frequency of negative emotions). The computed reliability Alpha is 0.8926.

Relations with family and friends (both items use a satisfaction scale of 1–5: not satisfied at all to highly satisfied).

Practicing religion (1–5 scale, where 1 = not at all, 5 = always).

Social trust (trust in others) on a 1–5 scale, where 1 = not trusted at all, 5 = highly trusted.

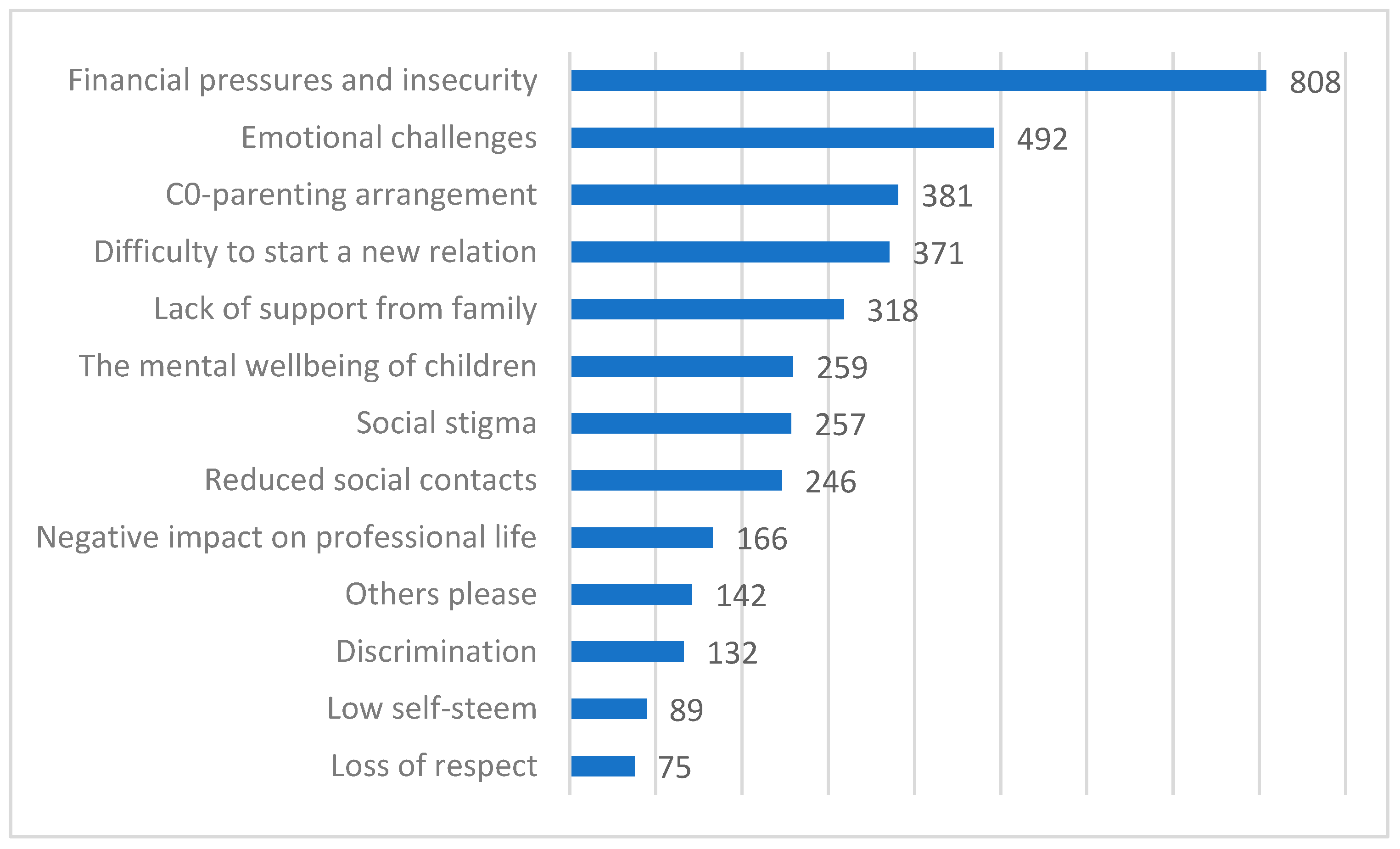

Post-divorce challenges (divorced women were asked to select the five biggest challenges that they have faced in their post-divorce life. Please see

Figure 1 for the choices).

Housing (residence) satisfaction (scale of 1–5: not satisfied at all to very satisfied).

Hours spent online (self-writing—hours spent online).

The Quality of Life Survey is an ongoing initiative by the Abu Dhabi Department of Community Development, launched in 2018. It aims to monitor social, economic, and health-related well-being across the emirate. Now in its fifth cycle (2023–2024), the survey uses stratified sampling to ensure representativeness across gender, age, nationality, and region. It covers a wide array of topics including income, housing, education, health, digital practices, and social connections. The data are publicly owned and managed by the Department, with over 100,000 participants in the latest wave, including 4347 divorced women.

To enhance comparative analysis, respondents were also categorized by age groups (20–24, 25–29, etc.), educational attainment (college degree or not), nationality (Emirati vs. Non-Emirati), and number of children (0, 1–2, 3–4, etc.). The dataset includes demographic controls such as employment status, housing conditions, and digital engagement.

3.2. Analytical Methods

To analyze the relationship between divorce-related challenges and well-being outcomes, the study employs a combination of descriptive statistics, ANOVA tests, and regression analysis. Mean scores are reported for key well-being indicators across different subgroups. One-way ANOVA is used to examine statistically significant differences in life satisfaction, mental well-being, and financial security across demographic categories (age, education, nationality, number of children). Post hoc tests (Tukey’s HSD) are applied where significant differences are detected to identify which groups differ from each other.

4. Results

4.1. Respondents

The 5th Cycle Quality of Life Survey in Abu Dhabi received responses from 100,048 individuals, of whom 4347 were divorced women, representing 4.3% of the total sample. Most divorced women fell within the 40–44 age group (923 respondents), followed by the 35–39 group (768 respondents) and the 45–49 group (811 respondents). Fewer respondents were aged 20–24 (32 respondents), indicating a lower prevalence of divorce among younger women. The number of respondents gradually declined after age 50. Emirati women comprised the majority of the sample (3271 respondents), while non-Emirati women accounted for 1076 respondents (

Table 1).

The sample included 2141 women with a college degree or higher and 2206 with education below a college degree, indicating a roughly equal representation of educational levels within the divorced subgroup. However, this distribution does not reflect the overall educational profile of the full female population in Abu Dhabi and, therefore, does not allow conclusions about the probability of being divorced conditional on education. Determining such probabilities would require a separate analysis comparing educational attainment among divorced and non-divorced women in the general population, ideally controlling for other relevant factors such as age, marital duration, and income level.

4.2. Divorce Challenges Reported by Women

Figure 1 presents the most significant challenges faced by divorced women in Abu Dhabi, as reported in the survey. Four challenges were cited substantially more often than others: financial insecurity (808 respondents), emotional distress (492 respondents), co-parenting difficulties (381 respondents), and difficulty starting a new relationship (371 respondents). These four categories represent key domains of financial, emotional, familial, and social concern. Other reported issues, such as discrimination or low self-esteem, were cited less frequently and were not analyzed in detail in this study.

4.3. Well-Being Determinants Among Divorced Respondents

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics of well-being determinants among divorced women who reported the four key challenges. Women reporting financial pressures had the lowest life satisfaction (5.63), household income satisfaction (2.34), and ability to pay for necessary expenses (1.91). These respondents also had the highest mental health composite scores (3.09), indicating greater levels of distress. Sleep quality and subjective health were also lower among women reporting financial insecurity. Women who reported emotional distress had a life satisfaction score of 6.27 and a mental health score of 3.01. Religious practice levels were highest among those facing financial pressures and emotional distress (both 4.55 and above). Hours spent online were highest (6.34) among those struggling with starting new relationships.

4.4. Divorce Impacts, Well-Being, and Age

The ANOVA results (

Table 3) show significant variations in well-being based on age among divorced women. Women aged 50 and above who experienced financial insecurity reported significantly lower life satisfaction (

p < 0.001). Life satisfaction scores for emotional distress were lower among women aged 30–44 (

p = 0.004). Co-parenting arrangements had the greatest impact on women aged 35–49, who recorded the lowest life satisfaction scores in this group (

p = 0.002). Women aged 50+ struggling with starting new relationships reported significantly lower life satisfaction (

p = 0.007). Significant age-based differences were also found in indicators such as mental health, income satisfaction, residence satisfaction, sleep quality, online engagement, and happiness across the four challenge categories.

4.5. Divorce Impacts and Number of Children

Table 4 presents the ANOVA findings based on the number of children. Statistically significant differences were observed in areas such as life satisfaction, household income, residence satisfaction, and religious practice. Women with five or more children who faced financial pressures reported the lowest satisfaction scores (

p = 0.021). Co-parenting difficulties were most impactful for women with 3–6 children (

p = 0.039). Emotional challenges and relationship difficulties did not vary significantly across the number of children, suggesting more consistent experiences across this variable.

4.6. Divorce Impacts for Emirati and Non-Emirati Divorced Women

Table 5 shows significant differences in well-being based on nationality. Non-Emirati women who reported financial pressures had significantly lower life satisfaction (

p = 0.017). Emirati women experiencing co-parenting difficulties also reported significantly lower life satisfaction (

p = 0.032). Emotional challenges and relationship difficulties did not show major variations between Emirati and non-Emirati women. Differences were also observed in mental health, trust in others, household income satisfaction, religious practice, and sleep quality based on nationality.

Table 6 presents the ANOVA results comparing women with and without a college degree. Women without a college degree who experienced financial insecurity reported significantly lower life satisfaction (

p = 0.009). Co-parenting challenges and emotional distress also yielded lower life satisfaction scores among less-educated women (

p = 0.031 and

p = 0.044, respectively). Differences in indicators such as residence satisfaction, sleep quality, and religious practice were also statistically significant across educational groups.

5. Discussion

This study offers a focused and empirically grounded examination of the well-being challenges faced by divorced women in Abu Dhabi. The findings reaffirm a growing body of international literature highlighting that divorce often leads to a multi-dimensional strain—emotional, financial, social, and relational—on women [

1,

2]. Yet, what emerges distinctively in this context is how these strains are shaped and amplified by the region’s unique socio-cultural and legal structures, which influence gender roles, family obligations, and societal perceptions of divorce.

Financial insecurity, identified as a primary concern, continues to be a critical issue for many divorced women. The gendered economic gap following marital dissolution is not new, but in Abu Dhabi, where traditional family systems often render women financially dependent on spouses, the abrupt shift in economic roles post-divorce can be particularly destabilizing. The findings support broader feminist economic theories that emphasize the structural disadvantages women face in the labor market after a marital breakdown [

33]. These results point to the need for institutional efforts to promote financial autonomy through training, employment placement, and policy reforms that enhance divorced women’s access to income-generating opportunities.

The emotional toll reported—ranging from sadness and anxiety to loss of identity—aligns with psychological models that frame divorce as a major life stressor, especially in the absence of strong social support systems [

34]. However, the cultural context in Abu Dhabi adds a unique layer: emotional distress may be internalized due to social expectations around endurance and familial honor. This context-specific dynamic highlights the importance of culturally attuned mental health interventions that are not only accessible but also sensitive to stigma and family dynamics. These services should ideally be embedded within trusted community structures, such as women’s associations or religious counseling centers.

Co-parenting difficulties, while globally recognized as a post-divorce challenge, are influenced in the UAE by legal interpretations of guardianship, custodial roles, and male authority within the family. Many women must navigate unclear boundaries in custody decisions, often without adequate mediation or legal literacy. This creates tension not only between former spouses but within the extended family network, impacting both the well-being of the mother and the children. Policies aimed at strengthening family courts, offering mediation programs, and training legal counselors in gender-responsive practice would be highly beneficial.

Equally important is the social stigma surrounding divorced women, particularly when it comes to the formation of new relationships. While divorce is legally permitted, it often carries a moral judgment that restricts women’s freedom to remarry or engage socially without being subject to scrutiny. This stigma may limit their mobility, autonomy, and sense of self-worth. These findings suggest that broader community education efforts are needed to reshape public narratives around divorce—moving from judgment and exclusion toward acceptance and support. Media campaigns, community dialogue initiatives, and school-based gender sensitization could play a role in transforming societal attitudes.

From a theoretical standpoint, the study reinforces intersectionality as a valuable lens. It is not divorce alone that affects well-being but the compounded effects of gender, economic dependency, cultural expectations, and limited institutional support. A divorced woman with low income, no employment, and dependent children faces a layered vulnerability that cannot be addressed by a one-size-fits-all intervention. This calls for a more integrated, multisectoral approach that includes housing, childcare, health services, and employment support.

Moreover, the findings carry important implications for social policy in Abu Dhabi. While various entities, such as the Family Care Authority and Department of Community Development, have taken strides toward improving women’s welfare, there remains a gap in the post-divorce landscape. Creating a comprehensive Post-Divorce Resilience Framework—combining legal guidance, emotional counseling, co-parenting support, and economic reintegration—could significantly mitigate the long-term negative impacts of divorce. Such frameworks should not only target divorced individuals but also engage their families and communities to foster a more inclusive and rehabilitative environment.

The study also highlights opportunities for future research. For instance, a longitudinal design could offer insights into the trajectory of well-being over time post-divorce, revealing both risk and resilience factors. Additionally, comparative studies including divorced men could illuminate gendered differences more systematically, offering a fuller picture of the post-divorce experience in the region. Future research could also examine the likelihood of divorce as a function of education and other demographic variables, using modeling techniques to assess conditional probabilities across the broader female population.

Finally, while this research is based on a robust, large-scale survey, it is not without limitations. The reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, and the exclusion of male respondents limits the generalizability of the findings across genders. Nevertheless, the insights provided are critical for both academic understanding and practical interventions targeting the post-divorce female population in the UAE.

6. Conclusions

This study provides an in-depth examination of the emotional, social, and economic realities of divorced women in Abu Dhabi, focusing on four major post-divorce challenges: financial insecurity, emotional distress, co-parenting difficulties, and struggles in forming new relationships. The findings reveal that these challenges significantly impact various well-being determinants, with financial pressures emerging as the most detrimental factor. Women facing financial insecurity reported the lowest life satisfaction scores, poorer subjective health, and increased mental distress, particularly among older divorcees and those without a college degree.

Age and education level played a notable role in shaping post-divorce experiences. Middle-aged women (35–49 years old) struggled the most with co-parenting responsibilities, balancing child rearing with career obligations. Older divorcees (50+) reported the greatest financial struggles and the lowest likelihood of forming new relationships, indicating potential social and economic vulnerabilities in later life. Additionally, non-Emirati women were disproportionately affected by financial insecurity, likely due to fewer social safety nets and legal protections, while Emirati women faced greater co-parenting stress, reflecting the complex family dynamics within the local cultural context.

Beyond economic and parenting difficulties, emotional well-being and social connectedness were significantly impacted. Women struggling with emotional distress and relationship difficulties reported lower life satisfaction, reduced social trust, and greater reliance on digital platforms for engagement. Interestingly, religious practices appeared to be a coping mechanism, with women facing social stigma and relationship difficulties engaging more frequently in religious activities. These findings highlight the multi-dimensional nature of post-divorce adjustment, where economic, social, and psychological factors interact in shaping overall well-being.

The study’s insights provide a critical foundation for understanding the unique struggles of divorced women in Abu Dhabi and emphasize the need for comprehensive social, economic, and psychological support systems to assist them in navigating post-divorce life.

Despite providing valuable insights into the emotional, social, and economic realities of divorced women in Abu Dhabi, this study has several limitations. First, the findings are based on self-reported survey responses, which may be influenced by subjective perceptions and response biases. Second, the study focuses only on divorced women, meaning that comparisons with divorced men or those in different marital statuses were not explored. Additionally, while the research highlights key well-being determinants, it does not account for longitudinal changes in post-divorce adjustment over time.

From a policy perspective, the findings underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions to support divorced women in Abu Dhabi. Financial assistance programs, job training initiatives, and affordable housing solutions could help mitigate the negative economic impact of divorce, particularly for those without a college degree. Psychosocial counseling services and community-based support networks are also critical to addressing emotional well-being and social reintegration. Furthermore, reforming co-parenting policies and legal frameworks could ease the burden of custody arrangements and improve the quality of life for divorced mothers. These findings have implications not only for social policy but also for psychiatric care planning and clinical mental health services that support women experiencing emotional distress and psychosocial dysfunction following divorce.

For future research, several directions can deepen the understanding of post-divorce well-being. Comparative studies examining the experiences of divorced men and women could offer a more gender-balanced perspective on post-marital challenges. In addition, longitudinal research tracking well-being over time would help identify patterns of adaptation and resilience across different phases of post-divorce life. Further exploration of cultural and legal factors influencing the divorce experience in the UAE and similar societies could also yield context-specific policy recommendations.

This study focused exclusively on the experiences of divorced women. However, future research should consider the broader impact of divorce on family members, including the psychosocial outcomes for older children and adolescents. Such perspectives would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of marital dissolution and support the development of inclusive interventions.

An important limitation of this study is the absence of data on the length of marriage prior to divorce and the age of children at the time of separation—both of which are critical in shaping post-divorce outcomes. Longer marital durations may be linked to deeper emotional and financial interdependencies, while younger children often heighten the complexity of co-parenting responsibilities. Without these variables, the analysis is limited in its ability to capture how family life-cycle dynamics influence post-divorce adjustment. Future studies should incorporate these dimensions to generate more nuanced insights into the trajectories of divorced women’s well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. (Mugheer Alkhaili) and M.B.; methodology, M.B.; software, A.A. (Asma Alrashdi); validation, M.A. (Mugheer Alkhaili), S.Y. and M.A. (Muna Albahar).; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.A. (Muna Albahar) and A.A. (Alanood Alsawai); resources, H.A.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, G.Y. and S.Y.; visualization, A.A. (Asma Alrashdi); supervision, H.A.; project administration, G.Y.; funding acquisition, H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been conducted and supported by research offices in the Department of Community Development and Statistics Centre Abu Dhabi. There was no funding provided to conduct this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Department of Community Development, United Arab Emirates (Approval Code: Ref. No. OUT/065/2024; Approval date: 14 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the Quality of Life Survey in Abu Dhabi.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical approval requirements.

Acknowledgments

This research paper benefited from the use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools to support the drafting, editing, and refinement of the text. AI assistance was used under the supervision of the lead researcher to enhance clarity, consistency, and organization of content. All data analysis, interpretation, and intellectual insights remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Amato, P.R. Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 650–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortelmans, D. Economic consequences of divorce: A review. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2020, 46, 471–490. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, P.A.; DiPrete, T.A. Losers and winners: The financial consequences of separation and divorce for men. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2001, 66, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, T.; Kalmijn, M. Is divorce more painful when couples have children? Demography 2016, 53, 1717–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes. The Financial Impact of Divorce; Forbes Finance Council: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbesfinancecouncil/2022/10/20/the-financial-impact-of-divorce/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Al Gharaibeh, F.; Islam, M.R. Divorce in the Families of the UAE: A comprehensive review of trends, determinants, and consequences. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2024, 60, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellar, S.; Smock, P.J. The economic consequences of divorce for women and children. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2005, 31, 295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra, D.A. Divorce and health: Current trends and future directions. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symoens, S.; Van de Velde, S.; Colman, E.; Bracke, P. Divorce and the multidimensionality of men and women’s mental health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 92, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, R.E. Renegotiating Family Relationships: Divorce, Child Custody, and Mediation; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.B.; Johnston, J.R. The alienated child: A reformulation of parental alienation syndrome. Fam. Court Rev. 2001, 39, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahadi, H.; Tajeri, B.; Haji Alizadeh, K. Developing a conceptual model of the factors forming divorce in the first five years of life: A grounded theory study. J. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziej-Zaleska, A.; Przybyła-Basista, H. Psychological well-being of individuals after divorce: The role of social support. Curr. Issues Pers. Psychol. 2016, 4, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizzi, J.M.; Koert, E.; Øverup, C.S.; Ciprić, A.; Sander, S.; Lange, T.; Schmidt, L.; Hald, G.M. Examining gender effects in postdivorce adjustment trajectories over the first year after divorce in Denmark. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhaheri, H.; Badri, M.; Alkhaili, M.; Yang, G.; Yaaqeib, S.; Albahar, M.; Alrashdi, A. How do health, social connections, housing, life values and trust matter for economic well-being—A path analysis of Abu Dhabi households. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Res. 2023, 13, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A.; Ahadi, H.; Tajeri, B.; Haji Alizadeh, K. Analysis of the experience of divorce from the perspective of divorced couples in Tehran. Women’s Strateg. Stud. 2020, 23, 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, I.-F.; Brown, S.L. The emotional and economic consequences of gray divorce. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.A. Women’s experiences of divorce in Saudi Arabia: An exploratory study. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2019, 20, 99–113. Available online: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss7/7 (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Hetherington, E.M.; Kelly, J. For Better or for Worse: Divorce Reconsidered; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Akpan, I.J.; Ezeume, I.C. The challenges faced by parents and children from divorce. Challenge 2020, 63, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, F.M.; Al-Kaabi, A.A. Divorce and its psychological impacts in the UAE: An exploratory study. Arab. J. Soc. Stud. 2021, 8, 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.B.; Emery, R.E. Children’s adjustment following divorce: Risk and resilience perspectives. Fam. Relat. 2003, 52, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Krenawi, A.; Graham, J.R. Culturally sensitive social work practice with Arab clients in mental health settings. Health Soc. Work 2000, 25, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanbekova, G.; Chung, M.C.; Abildina, S.; Sabirova, R.; Kapbasova, G.; Karipbaev, B. The impact of coping and emotional intelligence on the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder from past trauma, adjustment difficulty, and psychological distress following divorce. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, S.M.; Anderson, E.R.; Forgatch, M.S.; DeGarmo, D.S.; Hetherington, E.M. Risk and resilience after divorce. In Normal Family Processes: Growing Diversity and Complexity; Walsh, F., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 102–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kaleta, K.; Mróz, J. Posttraumatic growth and subjective well-being in men and women after divorce: The mediating and moderating roles of self-esteem. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmijn, M. The social consequences of divorce for adults: Social integration and support. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2018, 44, 399–424. [Google Scholar]

- Badri, M.; Alkhaili, M.; Aldhaheri, H.; Yang, G.; Yaaqeib, S.; Albahar, M.; Alrashdi, A. Spiritual resilience in the sands: Exploring religion and subjective well-being in Abu Dhabi’s community. Int. J. Relig. 2024, 5, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.M.; Spain, D. Divorce and economic outcomes: The effects of marital dissolution on financial well-being. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2020, 39, 537–559. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; DeVaney, S.A. The determinants of outstanding balances among credit card revolvers. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2003, 14, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Apata, O.E.; Falana, O.E.; Hanson, U.; Oderhohwo, E.; Oyewole, P.O. Exploring the effects of divorce on children’s psychological and physiological wellbeing. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2023, 49, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Menaghan, E.G.; Lieberman, M.A.; Mullan, J.T. The stress process. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1981, 22, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, M.; Uunk, W. Regional value differences in Europe and divorce risk. Eur. J. Popul. 2007, 23, 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson, D.; Williams, K.; Thomas, P.A.; Liu, H.; Thomeer, M.B. Race, gender, and chains of disadvantage: Childhood adversity, social relationships, and health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2014, 55, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).