Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has been raging around the world and public health measures such as lockdowns have forced people to go out less often, reducing sunlight exposure time, green space use, and physical activity. It is well known that exercise has a positive impact on mental health, but the impact of external environmental factors such as sunlight exposure and green space use on mental health has not been systematically reviewed. In this review, we categorized the major factors that may affect people’s mental health into (1) external environmental factors such as exposure to sunlight and green spaces, (2) internal life factors such as physical activity and lifestyle, and (3) mixed external and internal factors, and systematically examined the relationship between each factor and people’s mental health. The results showed that exposure to sunlight, spending leisure time in green spaces, and physical activity each had a positive impact on people’s mental health, including depression, anxiety, and stress states. Specifically, moderate physical activity in an external environment with sunlight exposure or green space was found to be an important factor. The study found that exposure to the natural environment through sunbathing and exercise is important for people’s mental health.

1. Introduction

External environments, including natural sunlight, has a significant impact on our mental health, but so far, few studies have comprehensively reviewed the relationship between mental health and the external environment. In particular, the COVID-19 pandemic has been currently spreading around the world since the end of 2019, forcing many countries and regions to lock down as a preventive measure against the outbreak. In such a situation, it is highly possible that not only the psychological frustration of not being able to go out freely, but also the substantial reduction in time and opportunities for physical contact with the external environment, including natural light, has had a significant negative impact on mental health.

Previous studies have shown that moderate exercise has a positive impact on mental health. Specifically, there is evidence that exercise interventions are effective in improving symptoms of depression [1,2], and that adding moderate exercise to behavioral therapy is also effective for depression [3]. Furthermore, there is evidence that exercise provides temporary relief from a variety of stresses for people, and that regular exercise can increase their feelings of self-efficacy [4]. In addition, regular exercise not only improves mental health, but also enhances the body’s immune capacity and leads to anti-inflammatory effects, which in turn reduces the risk of developing various chronic diseases [5].

However, although several studies have examined the relationship between mental health and exposure to external environments such as green spaces and sunlight through outings, their results have been mixed and have not been systematically reviewed. Particularly in the last two years, public health actions to control the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., quarantine, lockdown, self-isolation, maintenance of social distance, etc.) have reduced not only physical activity [4] but also inevitably resulted in reduced exposure to sunlight and green spaces due to the reduced frequency of going out.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to comprehensively review the effects of (1) external factors, including exposure to sunlight and green spaces, and (2) internal factors, such as physical activity and lifestyle, on mental health from relevant studies, and to investigate potential factors other than exercise that could contribute to the maintenance and improvement of mental health in the post-pandemic new normal era.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Research articles that examined human subjects written in English were screened by three authors (K.T., M.T., and Y.T.) using PubMed from November 2010 to December 2021. The search terms included ((depression OR (major depress*) OR (affective disorders) OR (mood disorders)) AND (sunlight OR daylight hours OR exercise) AND (outdoor OR indoor OR suburbs OR downtown OR rural OR urban OR nature).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In this study, we included the studies that investigated the effects of sunlight exposure, living environment, or level of daytime activity on mental health. First, we excluded the articles that examined non-humans as well as those that were written in languages other than English. Subsequently, two authors (M.T. and K.T.) screened all articles and double-checked them separately to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria. Among the studies examining the relationship between daytime activity and mental health, those that purely investigated the relationship between exercise and mental health were excluded from the scope of this review because the effectiveness of exercise on mental health is already well established. Any discrepancies regarding the screening results for the included studies were resolved through discussions with the senior author (Y.N.).

2.3. Data Extraction

In this review, we extracted data for each study on the author’s name, year of publication, country where the study was conducted, study design, subject attributes, sample size, mean age, clinical assessment, biometrics, medication, and key findings. Furthermore, based on the content of the research, each study was classified and summarized into two categories: (1) articles investigating the relationship between external factors, such as living environment and sunshine hours, and mental health, and (2) articles investigating the relationship between the individual’s internal factors, such as lifestyle and amount of activity during the day, and mental health. In this study, we did not conduct a meta-analysis for the results of each study because the results were mostly qualitative and there were no consistent quantifiable indicators.

3. Results

3.1. Article Identification

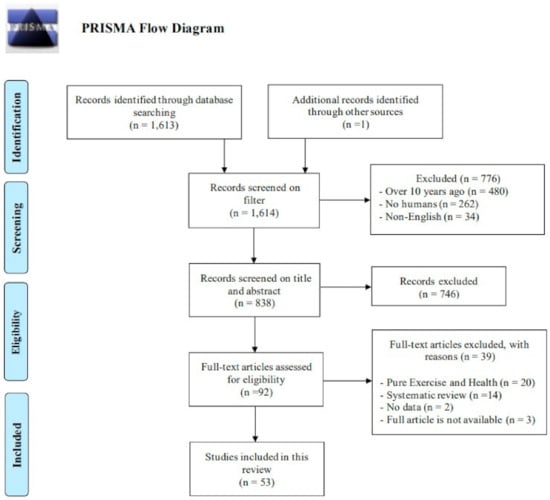

The initial database search identified 1613 articles and finally a total of 54 studies met the eligible criteria. The details regarding the included studies are summarized in Figure 1. We classified the included studies into three categories: (1) external factors, (2) internal factors, and (3) a combination of both, which are summarized in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. The following sections describe the study design, the location where the study was conducted, research subjects, clinical measures, and key findings.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for scoping review.

Table 1.

External factors including living environment and daylight hours.

Table 2.

Internal factors including lifestyle and physical activity.

Table 3.

Mixture of internal and external factors.

3.2. Study Design and Sample Characteristics of the Included Studies

Seven categories of study designs were identified among the included studies. Cross-sectional studies accounted for more than half of the included studies, or 33 out of 53. The majority of these studies were observational studies using questionnaires and other forms of surveys. The next most common type of study was longitudinal, with a total of 17 studies, including eight cohort studies and two case-control studies. In addition, there were a total of four intervention studies, including one crossover design and one clinical trial.

There were a total of 24 studies that examined the relationship between external environmental factors and mental health (Table 1).

Of these studies, 12 were related to living environments, and these environments included nature (seven studies), green spaces (two studies), and parks (three studies). In addition, eight of the studies focused on depression, four on depressive symptoms, two each on anxiety and stress states, and one on psychological distress. In addition, the studies targeting depression included one study looking at adolescent depression. There were a total of 12 studies on the relationship between sunshine duration and vitamin D intake and depression. Six studies assessed the relationship with depression, one of which was on geriatric depression. Two studies assessed depressive symptoms, and the other studies included one each assessing seasonal mood disorders, mood, and stress. An exception was the study by Wang et al., which assessed the relationship between depressive symptoms and PM2.5, and examined the effects of sunlight, physical activity, and neighborhood reciprocity on this association [6]. Two studies focused on both living environment and sun exposure, one investigating the effects of nature and sun exposure on mood and stress [7], and the other investigating the effects of natural environment and direct or indirect sun exposure on employees’ mental health and work attitudes [8]. As shown in Table 2, a total of 17 studies have investigated the relationship between an individual’s internal factors and mental health.

These studies are related to daytime activity levels and lifestyles, looking at the relationship between sitting time, leisure time, various physical activities, and overweight and depression. Among those studies, 13 studies targeted depressive symptoms, five targeted depression, and five targeted anxiety. There was a total of 12 other studies that included both internal individual and external environmental factors (Table 3). Most of the studies that included both factors examined the relationship between walking and depression in natural and urban environments. In addition, there were studies that examined the relationship between the presence of recreational facilities and mental health [9], between green spaces and exercise [10], and between nature experiences and depression [11]. Of those studies, three targeted depression, three examined depressive symptoms, and two investigated the relationship between depression and perceived stress. Moreover, three studies assessed mood, including mental well-being and emotional well-being.

3.3. Population and the Locations Where the Study Was Conducted in the Included Studies

Most of the articles included in this review were based on participants between the ages of 18 and 65. However, eight articles [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] studied participants younger than 18 years of age and discussed the association with adolescent depression. In addition, six articles [20,21,22,23,24,25,26] focused on the elderly. Although the articles included for this review varied in subject matter, two studies [21,27] limited their focus to patients with depression.

For the articles included in this review, the location of the study was across 21 countries. The most frequently surveyed region was the United States (n = 7) [8,17,18,20,28,29,30]. The next most common study areas were China (n = 6) [6,9,26,31,32,33], Korea (n = 6) [22,34,35,36,37,38], and the United Kingdom (n = 6) [10,39,40,41,42,43]. They were followed by five studies in Japan (n = 5) [15,44,45,46,47], three studies in the Netherlands [7,27,48], two studies in Australia [49,50], and two studies in Austria [21,51]. In addition, one study was conducted in each of the following countries: Vietnam [52], Austria [21], Canada [19], Scotland [53], United Arab Emirates [54], Malaysia [55], Brazil [12], India [56], Sweden [11], Denmark [57], Finland [25], and Estonia [24]. In one study [58], eight European countries were included; in another study [58], eight European countries were included: Lithuania, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Portugal, Hungary, Slovakia, and France. In addition, in another study [16], the survey was conducted in countries participating in the Global School-Based Student Health Survey (GSHS).

3.4. Clinical Measures That Used in the Included Studies

Either DSM-IV, DSM-5, or ICD-10 was used to diagnose depression. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale was the most commonly used scale to assess depression and was used in 11 articles. The Profile of Mood States (POMS) and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) were also commonly used to assess mood, with three articles each. Other studies used their own questionnaires or other symptom assessment batteries, and there was no uniformity.

3.5. Key Findings

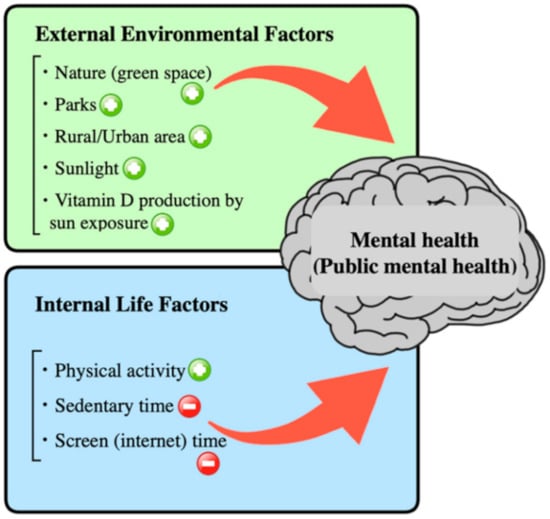

Based on the key findings of this review, Figure 2 briefly summarizes the external and internal risk factors that can affect people’s mental health.

Figure 2.

Graphical summary of this review: those that show a positive impact on mental health are marked with a symbol of +, while those that have a negative impact are marked with a symbol of −.

3.5.1. External Factors

Relationship between nature (green space) and mental health: There were eight studies that examined the relationship between nature (green space) and mental health (see Table 1). The diseases and conditions targeted in these included studies were as follows: depression was reported in four cases [32,42,49,50], depressive symptoms in three [8,20,25], and mood in one [7]. Furthermore, three studies examined the relationship with anxiety and stress [8,20,49]. In a study investigating the relationship between exposure to green space in residential areas and depression, the degree of green space exposure was correlated with less depressive symptoms (r = −0.386, p < 0.05) [32]. In addition, Cox et al. also suggested that three factors in particular (frequency: p < 0.001; duration: p < 0.05; and intensity: p < 0.01) of nature exposure were positively associated with depression [42]. Furthermore, Beute and de Kort demonstrated that nature exposure was associated with better affective states [7]. In addition, the study by Shanahan et al. showed that people who go outdoors to a green space for 30 min or more per week may have up to a 7% lower risk of developing depression and up to a 9% lower risk of developing hypertension [50]. However, Pun et al. found that living in a green space was not significantly associated with lower anxiety and depression scores [20], and Rantakokko et al. also reported that diversity of nature was not associated with lower depressive symptoms [25]. Furthermore, Dean et al. reported that, paradoxically, the greater the involvement with nature, the greater the degree of depression, anxiety, and stress [49]. Thus, no consistent results were found for the relationship between nature (green space) and mental health.

Relationship between parks and mental health: There were two studies that investigated the relationship between the presence of parks and depression. One study by Min et al. found that adults with few parks in their neighborhoods had a 16–27% higher risk of depression and suicide than adults with many parks in their neighborhoods [34]. Another study by Mukherjee et al. found that people who lived far from a park were 3.1 times (95% CI: 1.4–7.0) more likely to develop depression than those who lived closer to a park [56]. Both of these results have in common that the presence of a park close to the living environment may work positively in preventing the onset of depression.

Relationship between rural/urban area and mental health: There were five studies that examined the relationship between urban or rural area of residence and mental health, and the diseases and conditions targeted were depression in two studies and depressive symptoms in two studies. A study conducted on adolescent depression showed that 32.5% of rural students and 35.1% of urban students had depressive symptoms, and the attributes that made them less likely to suffer from depression in the adolescent population were being male (OR: 1.44; 95% CI 1.72–1.75, p < 0.001) and having an exercise habit (OR: 0.56; 95% CI 0.46–0.69, p < 0.001) [31]. Furthermore, Tan et al. reported the prevalence of depression among the poor in urban areas of Malaysia as 12.3%, and the factors significantly associated with depression included age below 25 years, male, living in the area for less than 4 years, and those who did not exercise regularly [55]. In addition, Chung et al. investigated the relationship between city size and risk factors for the development of depressive symptoms in the elderly and found that living in medium-sized cities or rural areas was a significant risk factor for the development of depressive symptoms in the elderly [36]. Other risk factors for the development of depressive symptoms in the elderly included male sex, age between 53–60 years, and lack of regular exercise. In a study examining the relationship between depressive symptoms and socio-environmental factors in a rural, depopulated inland area, the lifestyle-related factor most strongly associated with depression was “anxiety about interpersonal relationships” (odds ratio (OR): 2.7; 95% CI: 2.06–3.53, p < 0.0001) [44]. Although these results did not show consistent results for mental health in urban and rural areas, the study by Deng et al. showed that regular exercise may have a positive impact on mental health [9].

Relationship between sunlight and mental health: In this systematic review, seven studies investigated the relationship between sunlight exposure and mental health. A study examining daytime sunlight exposure and mood in UK adults found that an additional hour spent outdoors during the day was associated with a lower lifetime risk of depression (OR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.92–0.98), less frequent use of antidepressant medication (OR: 0.95; 95% CI 0.92–0.98), less loss of pleasure and lower mood (OR: 0.88; 95% CI 0.87–0.89), greater self-reported happiness (OR: 1.45; 95% CI 1.41–1.48), and lower neuroticism (incidence rate ratio (IRR): 0.96; 95% CI 0.95–0.96) [43]. Furthermore, the other study investigating the effects of nature and sunlight exposure on mood and stress states showed that daylight exposure has beneficial effects on mood [7]. In a study examining the relationship between self-reported exposure to natural light in the living environment and the onset of depression, those who reported inadequate exposure to natural light in their living environment were 1.4 times (95% CI: 1.2–1.7) more likely to report having depression than those who did not [58]. An et al. investigated the effects of direct and indirect sunlight exposure on employees’ mental health and work attitudes and reported that lack of direct sunlight was a major predictor of anxiety, and lack of indirect sunlight was a major predictor of the emergence of depressed mood, job satisfaction and organizational commitment [8]. Furthermore, Sarran et al. investigated the relationship between the duration and amount of natural light exposure and depressive symptoms in patients with seasonal affective disorder, suggesting that shorter daylight duration at the time of the study and the week before, and lower total amount of daylight exposure in the week before the time of the study, were significantly correlated (r = 0.22, p < 0.001) with worse depressive symptoms [27]. In addition, a study examining the relationship between meteorological factors and depression due to air pollutants noted that as air pollutants increase, the amount of sunlight transmitted to the earth’s surface decreases, thereby reducing the amount of effective sunlight, which in turn may increase the risk of developing depression [37]. Finally, the study by Wang et al. focuses on sunlight exposure, physical activity, and reciprocal relationships with neighbors as factors that influence the relationship between PM2.5-induced air pollution and depression. The results suggest that increased PM2.5 concentrations were closely associated with worsening depressive symptoms, probably through decreased sun exposure, less physical activity, and less interaction with neighbors [6]. Thus, these nine studies consistently demonstrate the potential for natural light to have a positive impact on mental health [6,7,8,27,37,43,58]. On the other hand, in an interesting study, Canazei et al. examined the acute effects of room lighting on mood in patients with mild geriatric depression and found that artificial sunlight could produce a significant subjective sedative effect (p = 0.029, η2 = 0.218) compared to standard white light [21].

Relationship between vitamin D production by sun exposure and mental health: Thomas et al. conducted an intervention study in which female college students with vitamin D deficiency and depressive symptoms were divided into a behavioral activation program intervention group or a waiting list control group with an emphasis on sunbathing with the aim of investigating the relationship between the two [54]. The results showed that while vitamin D deficiency worsened in the control group, blood levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D increased significantly in the behavioral activation group, which focused on sunbathing, and vitamin D deficiency was alleviated. There was also an improvement in depressive symptoms in the intervention group compared to the control group (r = −0.18, p = 0.02). In a study of elderly people in Korea, as compared with a normal group of men with serum 25 hydroxyvitamin D concentrations of 30.0 ng/mL or higher, people with serum 25 hydroxyvitamin D concentrations of 20.0–29.9 ng/mL had an OR of 1.74 (95% CI: 0.85, 3. 58), those with 10.0–19.9 ng/mL had an OR of 2.50 (95% CI: 1.20, 5.18), and those with <10.0 ng/mL had an OR of 2.81 (95% CI: 1.15, 6.83), even after adjusting for each clinico-epidemiological variable, indicating that they were more likely to develop depressive symptoms. On the other hand, no significant relationship between serum 25 hydroxyvitamin D concentration and depressive symptoms was observed in women, regardless of adjustment by clinico-epidemiological variables [22]. Moreover, a cohort study on the long-term course and outcome of depression and anxiety disorders using a subset of the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety Disorders (NESDA) found that compared with healthy controls, participants with depressive episodes had significantly lower serum 25 hydroxyvitamin D concentrations (p = 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.21). Furthermore, participants with the most severe depressive symptoms showed the lowest serum 25 hydroxyvitamin D concentrations (p = 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.44) [48]. The results of these three studies are consistent, showing that blood levels of 25 hydroxyvitamin D are decreased in depressed patients.

3.5.2. Internal Life Factors

Relationship between physical activity and mental health: Of the 17 studies summarized in Table 2, there were 10 studies that investigated physical activity and mental health [13,14,19,23,24,26,33,38,46,51]. Three of those studies showed that physical activity may have a positive effect on depression [23,26,33], and one study in particular, by Wang et al. concluded that physical exercise three or more times a week, regardless of intensity, may reduce the risk of developing depression [33]. In terms of the relationship between physical activity level and risk of depression, Wang et al. found that moderate to high intensity physical activity [26] and Lee et al. showed that prolonged physical activity [23] reduced the risk of depression. In addition, Julien et al. focused on walking as a form of physical activity and investigated the relationship between walking and depressive symptoms. They found that those with more depressive symptoms were associated with a decrease in subsequent walking time [24]. In addition, with one exception, Hehn et al. found that outdoor work in winter had a positive impact on mood, but no particular impact on depression itself [57]. Xu et al. also examined the relationship between multiple lifestyle factors and depression. Higher sleep quality (OR: −3.92; 95% CI: −4.49, −3.35, p < 0.01) and duration (OR: −1.79; 95% CI: −2.49, −1.09, p < 0.01), more physical activity (OR: −0.83; 95% CI: −1.27, −0.40, p < 0.01), and more outdoor activity (OR: −1.07; 95% CI: −1.64, −0.51, p < 0.01) were significantly associated with lower depressive symptoms as assessed by the CES-D score [17].

Relationship between sedentary time and mental health: Nam et al. examined the relationship between sedentary time and depression and found that those who sat for 8–10 h (OR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.15–2.11) or more than 10 h (OR: 1.71; 95% CI: 1.23–2.39) had an increased risk of developing depression compared to those who sat for less than 5 h per day [35]. Two other studies examined sedentary time and depressive symptoms. Vancampfort et al. found that the degree of depressive symptoms increased linearly with an increase in sedentary time of 3 h per day [16], while Pengpid et al. found that the odds ratios for the degree of anxiety and depressive symptoms plateaued and did not change with longer sedentary times of 8 h or more [52]. Thus, the above three studies showed that long sedentary time can have a negative impact on mental health.

Relationship between screen (internet) time and mental health: Although the number of studies on this topic is limited, increased screen time is associated with physical inactivity and may slightly increase the risk of developing anxiety and depressive symptoms [41]. In addition, the study in Kojima et al. found a significant association between problematic Internet use (PIU) and psychological factors such as depressive symptoms (OR: 1.83; 95% CI: 1.23–2.71) and orthostatic dysregulation (OD) symptoms (OR: 1.81; 95% CI: 1.11–2.98) [15].

3.5.3. Mixture of External and Internal Factors

Relationship between walking in natural environment and mental health: There were five studies that examined the relationship between walking and mental health in external natural environments (see Table 3). A study by Berman et al. showed that walking in a natural environment may improve cognitive and emotional functioning [29], while a study by Marselle et al. indicated that frequent nature appreciation may be associated with reduced stress levels, depressive symptoms, and negative emotions, and increased self-esteem and mental well-being [40]. A study conducted on healthy female college students by Song et al. also showed that walking in a forested area resulted in a significantly lower degree of symptoms associated with mood disorders than walking in an urban area (Total mood disturbance score of the POMS: forest: 0.1 ± 4.9; city: 7.7 ± 7.3; p < 0.01) [45]. Furthermore, Song et al. showed that walking in a forest increased feelings related to “comfort”, “relaxation”, “nature”, and “energy” and decreased feelings related to “tension-anxiety”, “depression”, “anxiety-hostility”, “fatigue”, and “confusion” for participants compared to walking in an urban environment [47]. On the other hand, Bratman et al. examined the relationship between exposure to the natural environment and frontal lobe function in healthy participants and found that a 90-min nature walk resulted in a decrease in self-reported rumination symptoms and a decrease in subgenual anterior cingulate cortex activity, whereas an urban walk did not induce these effects [11]. The results of these studies consistently show that walking in a natural environment can have positive effects on mental health.

Relationship between group walking and mental health in urban and rural areas: There were two studies that examined group walking and mental health in urban and rural environments for healthy participants [53,59]. Marselle et al. also reported that group walks in a green space significantly contributed to reduced perceived stress (B = −1.14, SE = 0.26, β = −0.08) and negative affect (B = −0.62, SE = 0.23, β = −0.05), but were not specifically associated with improved depressive symptoms (B = −0.08, SE = 0.02, β = −0.12) or increased positive affect (B = 1.78, SE = 0.30, β = 0.11) [59]. In addition, a study by Roe et al. conducted in healthy participants showed that walks in rural areas may be more effective in restoring emotional and cognitive functions (p < 0.01) than walks in urban areas [53]. These results commonly suggest that walking in rural areas may be more beneficial for stress and emotions than walking in urban areas.

Relationship between physical activity and mental health in other settings: A study by Orstad et al. examined the relationship between park-based physical activity and mental distress, and found that proximity to a park from the residence may be indirectly associated with fewer days of mental health problems through physical activity in the park only among those who were not concerned about crime in the park (index of moderated mediation = 0.04; SE = 0.02; bootstrap-generated 95% bias-corrected CI = 0.01–0.10) [28]. On the other hand, Deng et al. examined the relationship between the availability of recreational facilities in residential areas and depressive symptoms and found that the availability of recreational facilities was higher in urban areas than in rural areas (Cohen’s d = 1.05), which may have led to higher leisure time physical activity (the standardized path coefficient β = 0.080) and lower depressive symptoms (rural: β = 0.349; urban: β = 0.332) than rural residents. In fact, the degree of engagement in leisure time physical activity was relatively lower among rural residents compared to urban residents [9]. Furthermore, a study by Barton et al. conducted on participants experiencing a variety of mental health problems reported significant group differences in the improvement of both self-esteem (F1,147 = 38.2, p < 0.001) and mood level (F1,142 = 65.8, p < 0.001) after 6 weeks of intervention in the group that exercised in a green space compared to the group that engaged in social activities [10]. In addition, James et al. also assessed the cross-sectional relationship between walkability index and depression in a low-income, ethnically diverse population living in the southeastern United States with the aim of investigating which factors in the urban environment may pose a risk for adverse mental health outcomes. The results showed that participants living in areas with the highest walkability index had 6% higher odds of moderate or greater depressive symptoms (95% CI = 0.99–1.14), 28% higher odds of a depression diagnosis (95% CI = 1.20–1.36), and 16% higher odds of currently using antidepressants (95% CI = 1.08–1.25) compared to participants living in the lowest walkability index areas [30].

4. Discussion

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive review of the impacts of the external environment, including natural sunlight, on human mental health, taking into account the relationship with internal factors such as lifestyle and exercise habits. The results showed that exposure to sunlight is beneficial for maintaining and improving people’s mental health. In particular, spending time in green areas and parks is associated not only with exposure to sunlight, but also with the promotion of physical activity, which may contribute to improving mental health. Furthermore, exposure to sunlight, the presence of greenery near the residence, and increased interpersonal interaction had beneficial effects on the maintenance and improvement of mental health, suggesting that contact with the external natural environment is biologically important for human mental health.

4.1. Relationship between Living Environment and Mental Health

In terms of the relationship between living environment and mental health, the studies summarized in Table 1 did not show consistent results between urban and suburban/rural areas. However, it was found that the presence of available green spaces [20,25,32,42,49,50] and parks [34,56] around the living environment had a positive impact on mental health. The presence of green space around the living environment tends to have a positive impact on mental health, and this may be due in part to the high likelihood of exposure to sunlight in green space and natural environments. In addition, as reported by Wang et al., air pollution such as PM2.5 may have a negative impact on mental health, partially because it reduces the duration of sunlight exposure. However, some of the studies included in this study did not show positive effects on mental health in rural areas with a lot of nature and green spaces [6], suggesting that the use and purpose of green spaces and parks may be more important than their existence itself. In other words, although there are more extensive green areas in rural areas, they do not contribute much to mental health if their primary use is for farming as a work. In contrast, if the purpose of the green area is for exercise and recreation, it appears to have a positive effect on mental health, regardless of whether the area is located in an urban or suburban/rural area [32]. Other included studies [32,44] suggested the importance of exposure to the natural environment as well as opportunities for interpersonal interaction.

Furthermore, rural areas have a relatively large older population, which differs from the composition of the urban population, making it difficult to compare the effects of external and internal factors directly in terms of public mental health. Moreover, rural areas are often medically depopulated and poorly served by public transportation, which usually makes it difficult to access medical institutions specializing in mental health [44]. However, this reflects the reality of super-aging societies in certain developed countries, where further depopulation of rural areas may become a major problem in the mental health of the elderly. On the other hand, another study showed that the prevalence of depression was higher among the urban poor, which makes it difficult to interpret the relationship between external environment and mental health based on regional classifications such as urban and rural areas [55]. Again, regarding the relationship between sunlight exposure and mental health, all of the included studies except one [7] showed that sunlight may positively affect people’s mental health [6,8,12,21,27,37,43,58]. However, the study by Beute et al. did not show a direct effect of exposure to natural environment and sunlight exposure on emotional states but profiled higher hedonic tone and energy levels and lower tension levels in environments with higher exposure to both natural environment and sunlight, suggesting that, at least in part, sunlight exposure contributes to improved human mental health [7].

Some studies [22,48,54] have also reported that low vitamin D levels in the blood are associated with depressive symptoms. Since vitamin D is known as the sunshine vitamin [60] (i.e., vitamin D is produced in the skin through exposure to sunlight), it is conceivable that exposure to sunlight may also be beneficial in preventing or improving depression. In addition, Caccamo et al. also summarized the health risks of vitamin D deficiency from a biological function perspective and reported an association with neuropsychiatric disorders [61]. However, a recent meta-analysis that examined the efficacy of vitamin D for antidepressant effects on depression did not show consistent results [62]. Indeed, one previous study examined the relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25-(OH) D] levels and depressive symptoms in overweight and obese subjects in a cross-sectional and RCT design to evaluate the effect of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms. The two groups treated with vitamin D showed significant improvement in BDI scores after one year, while the placebo group did not. This study suggests that there may be a relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and depressive symptoms, and that high-dose vitamin D supplementation may improve these symptoms [63]. On the other hand, another RCT showed that vitamin D deficiency may not be associated with an increased risk of depression in people without clinically significant depression, indicating that the use of vitamin D supplementation may not be effective in reducing depressive symptoms in this population [64]. Thus, although there may be an association between mental health problems, including neuropsychiatric disorders, and vitamin D deficiency, further large clinical studies are needed to determine the beneficial effects of vitamin D on mental health, especially for those who spend more time indoors and less time exposed to sunlight.

In addition, even if people spend their time in a suburban environment with plenty of nature rather than in urban areas, long hours of transportation by car may not only cause mental fatigue from driving, but also undermine the positive effects of the natural environment because people are confined in cars [65,66].

Taken together, these results suggest that spending time in external environments, such as green spaces and parks, is more likely to promote sunlight exposure than spending time indoors and consequently contribute to the maintenance and improvement of people’s mental health, although this is partly due to the fact that its use is often originally based on positive aspects such as exercise and recreation.

4.2. Relationship between Internal Factors and Mental Health

Regarding the relationship between internal factors/lifestyle and mental health (see Table 2 and Table 3), a number of studies have reported that daily exercise habits [14,17,18,23,26,33,38,46,51,52,59] have a positive impact on mental health in general, while sedentary lifestyle [16,23,24,35,46,52] and long screen time [15,41] increase the risk of depression. Although several previous studies [9,10,19,24,57] have shown that exercise does not always have a positive impact on mental health for clinical populations experiencing a variety of mental health problems, a study by Barton et al. reported that mood disturbances and low self-esteem generally improve after participation in any exercise program [10]. Buchan et al. [19] showed that increased moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was associated with decreased anxiety and depressive symptoms in men. In addition, a study by Hahn et al. [57] showed that outdoor work in winter, with its short daylight hours, did not have a particularly negative effect on the development of depression, but rather could have a beneficial effect on mood, suggesting that exercise itself may have, at least in part, an antidepressant effect. On the other hand, interestingly, a study by Julien et al. [24] found no significant association between the amount of walking and depressive symptoms when assessed cross-sectionally, but showed that subjects with more depressive symptoms tended to walk less frequently afterwards, indicating that longitudinally, depressive symptoms may cause a decrease in walking frequency.

Furthermore, the study by Deng et al. [9] showed that the use of recreational facilities may increase people’s physical activity in urban areas compared to rural areas. However, the study did not examine the direct effect of recreational facilities on the reduction of depressive symptoms in urban areas. In any case, the results suggest that people’s lifestyles may change depending on the external environment. A meta-analysis published in 2018 concluded that for mild to moderate depression, the effects of exercise are comparable to those of antidepressants and psychotherapy, and for more severe depression, exercise is a valuable complement to conventional treatments [67]. Collectively, these results suggest that increased daily activity, including exercise, may have a positive impact on mental health apart from exposure to green space and sunlight in the external environment that has been previously reported. It is also possible that factors inhibiting sun exposure and exercise may include the indoor working environment and the working hours during the day. Thus, increased flexibility in working hours may play an important role in improving mental health.

4.3. Relationship between Mixture of Internal/External Factors and Mental Health

On the other hand, as we summarized in Table 3, a mixture of internal factors such as physical activity as well as specific external environmental factors such as walking activity in rural areas and green spaces decreases stress and negative emotions [40,45,47,59], increases memory performance [29,53], promotes emotional and cognitive recovery [53], and decreases activity in brain regions associated with mental illness [11]. Furthermore, a study by Shanahan et al. [50] showed that visiting a green space at least once a week for an average of 30 min or more can prevent depression by up to 7%, suggesting that daily habits such as frequent visits to green spaces may reduce the risk of developing depression.

In addition, an exercise experiment [9] conducted under the condition of viewing images of a cycling course rather than an actual green space reported less mood disturbance and perceived exhaustion compared to the achromatic or red filtered image condition, indicating that green-related visual stimuli may also have a synergistic effect on the anti-stress effects of exercise. Other studies using light stimuli have also shown that exposure to green or blue light reduces anxiety [68] and increases calmness [69], suggesting a close relationship between light exposure and mental health. Therefore, moderate exercise in specific external environments or environments that mimic external environments may play an important role in the maintenance and improvement of mental health. Furthermore, with respect to external environmental factors, light stimulation at specific wavelengths may serve as a key to the effects on mental health. In addition, interestingly but paradoxically, living in a walkable neighborhood was associated with a slightly higher diagnosis of depression and level of antidepressant use, and walkability was associated with greater depressive symptoms in more deprived neighborhoods. While dense urban environments may provide opportunities for physical activity, they may also increase exposure to noise, air pollution, and social stressors, which may increase levels of depression [30].

Future directions: High intensity light therapy with white light has been used mainly for seasonal affective disorder, and further, previous studies [70,71] have shown that such light therapy is also useful for non-seasonal depression. For example, previous studies that examined the effects of blue light on sleep, memory, and emotion have shown beneficial influences [72,73]. At the same time, however, a review conducted by Bauer et al. reported that blue light may also interfere with sleep [74]. Furthermore, violet light stimulation was found to improve cognitive function in aged mice and to ameliorate depression-like symptoms in mice induced by social defeat stress [75]. Specifically, since violet light is not contained in fluorescent lamps or white LEDs, it is necessary to examine in detail the effects of blue light or violet light among the visible light with shorter wavelengths on mental health. Thus, as a rational and feasible intervention method for maintaining and improving people’s mental health in the post-COVID-19 era of the new normal, applications such as neuromodulation using light stimulation that mimics natural light could be expected in the future.

There were several limitations in this study. First, this review was not able to conduct a meta-analysis because there were no quantifiable measures that were commonly used in each study. In addition, since various potential confounding factors, such as individual genetic background, lifestyle, health care system and its level in each country, and air pollution in each region, may be involved in most of the included studies in this review, the studies must inevitably be interpreted qualitatively from a macroscopic perspective. In fact, it is difficult to strictly control the potential confounding factors in the real-world setting. In the future, it is necessary to investigate, for example, whether non-invasive light stimulation with specific wavelengths is clinically useful for maintaining and improving people’s mental health using randomized controlled trials with sufficient sample size.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically reviewed the effects of exposure to sunlight and green spaces and physical activity on people’s mental health. The results showed that exposure to sunlight, exposure to and use of green spaces, and physical activity each positively affected mental health. The use of green space was also associated with exposure to sunlight and promotion of physical activity, suggesting that internal factors as represented by moderate physical activity under specific external conditions or in an environment that mimics the external environment may contribute to further improvement of mental health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N. and K.T. (Keita Taniguchi); methodology, Y.N.; validation, K.T. (Keita Taniguchi); formal analysis, K.T. (Keita Taniguchi); investigation, K.T. (Keita Taniguchi), M.T. and Y.T.; data curation, K.T. (Keita Taniguchi); writing—original draft preparation, K.T. (Keita Taniguchi) and Y.N.; writing—review and editing, S.N., M.H., M.M., K.T. (Kazuo Tsubota) and Y.N.; visualization, K.T. (Kazuo Tsubota); supervision, Y.N.; project administration, Y.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Y.N. received a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (21H02813) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), research grants from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), investigator-initiated clinical study grants from TEIJIN PHARMA LIMITED (Tokyo, Japan) and Inter Reha Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Y.N. also received research grants from Japan Health Foundation, Meiji Yasuda Mental Health Foundation, Mitsui Life Social Welfare Foundation, Takeda Science Foundation, SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation, Health Science Center Foundation, Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research, Taiju Life Social Welfare Foundation, and Daiichi Sankyo Scholarship Donation Program. Y.N. received speaker’s honoraria from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, MOCHIDA PHARMACEUTICAL CO., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), Yoshitomiyakuhin Corporation, and TEIJIN PHARMA LIMITED within the past three years. Y.N. also received equipment-in-kind support for an investigator-initiated study from Magventure Inc. (Farum, Denmark), Inter Reha Co., Ltd., Brainbox Ltd. (Cardiff, United Kingdom), and Miyuki Giken Co., Ltd. S.N. received a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists A and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research B and C from JSPS, and research grants from Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology, Naito Foundation, Takeda Science Foundation, Uehara Memorial Foundation, and Daiichi Sankyo Scholarship Donation Program within the past three years. S.N. also received research support, manuscript fees or speaker’s honoraria from Dain-ippon Sumitomo Pharma, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, Qol Co., Ltd., TEIJIN PHARMA LIMITED, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited within the past five years. M.M. received grants and/or speaker’s honoraria from Asahi Kasei Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Fuji Film RI Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kracie, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Novartis Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, Z.; Lan, W.; Yang, G.; Li, Y.; Ji, X.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S. Exercise Intervention in Treatment of Neuropsychological Diseases: A Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 569206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, M.C.; Bailey, A.P.; Craike, M.; Carter, T.; Patten, R.; Stepto, N.K.; Parker, A.G. Exercise Interventions for Mental Disorders in Young People: A Scoping Review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2019, 6, e000678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbeau, K.; Moriarty, T.; Ayanniyi, A.; Zuhl, M. The Combined Effect of Exercise and Behavioral Therapy for Depression and Anxiety: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, R.J.; Verde, T.J.; Thomas, S.G.; Shek, P. Physical Activity and the Immune System. Can. J. Sport Sci. 1991, 16, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petruzzello, S.J.; Landers, D.M.; Hatfield, B.D.; Kubitz, K.A.; Salazar, W. A Meta-Analysis on the Anxiety-Reducing Effects of Acute and Chronic Exercise. Outcomes and Mechanisms. Sports Med. 1991, 11, 143–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Xue, D.; Yao, Y.; Liu, P.; Helbich, M. Cross-Sectional Associations between Long-Term Exposure to Particulate Matter and Depression in China: The Mediating Effects of Sunlight, Physical Activity, and Neighborly Reciprocity. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 249, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beute, F.; de Kort, Y.A.W. The Natural Context of Wellbeing: Ecological Momentary Assessment of the Influence of Nature and Daylight on Affect and Stress for Individuals with Depression Levels Varying from None to Clinical. Health Place 2018, 49, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, M.; Colarelli, S.M.; O’Brien, K.; Boyajian, M.E. Why We Need More Nature at Work: Effects of Natural Elements and Sunlight on Employee Mental Health and Work Attitudes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Paul, D.R. The Relationships Between Depressive Symptoms, Functional Health Status, Physical Activity, and the Availability of Recreational Facilities: A Rural-Urban Comparison in Middle-Aged and Older Chinese Adults. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 25, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.; Griffin, M.; Pretty, J. Exercise-, Nature- and Socially Interactive-Based Initiatives Improve Mood and Self-Esteem in the Clinical Population. Perspect. Public Health 2012, 132, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Hahn, K.S.; Daily, G.C.; Gross, J.J. Nature Experience Reduces Rumination and Subgenual Prefrontal Cortex Activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8567–8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levandovski, R.; Pfaffenseller, B.; Carissimi, A.; Gama, C.S.; Hidalgo, M.P.L. The Effect of Sunlight Exposure on Interleukin-6 Levels in Depressive and Non-Depressive Subjects. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macgregor, A.P.; Borghese, M.M.; Janssen, I. Is Replacing Time Spent in 1 Type of Physical Activity with Another Associated with Health in Children? Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 44, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleppang, A.L.; Hartz, I.; Thurston, M.; Hagquist, C. The Association between Physical Activity and Symptoms of Depression in Different Contexts-a Cross-Sectional Study of Norwegian Adolescents. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, R.; Sato, M.; Akiyama, Y.; Shinohara, R.; Mizorogi, S.; Suzuki, K.; Yokomichi, H.; Yamagata, Z. Problematic Internet Use and Its Associations with Health-Related Symptoms and Lifestyle Habits among Rural Japanese Adolescents. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 73, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J.; Van Damme, T.; Koyanagi, A. Sedentary Behavior and Depressive Symptoms among 67,077 Adolescents Aged 12–15 Years from 30 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Qi, J.; Yang, Y.; Wen, X. The Contribution of Lifestyle Factors to Depressive Symptoms: A Cross-Sectional Study in Chinese College Students. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 245, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, F.; Francis, L.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Isasi, C.R. Depressive Symptoms Are Associated with Excess Weight and Unhealthier Lifestyle Behaviors in Urban Adolescents. Child. Obes. 2014, 10, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, M.C.; Romano, I.; Butler, A.; Laxer, R.E.; Patte, K.A.; Leatherdale, S.T. Bi-Directional Relationships between Physical Activity and Mental Health among a Large Sample of Canadian Youth: A Sex-Stratified Analysis of Students in the COMPASS Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pun, V.C.; Manjourides, J.; Suh, H.H. Association of Neighborhood Greenness with Self-Perceived Stress, Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Older U.S Adults. Environ. Health A Glob. Access Sci. Source 2018, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canazei, M.; Pohl, W.; Bauernhofer, K.; Papousek, I.; Lackner, H.K.; Bliem, H.R.; Marksteiner, J.; Weiss, E.M. Psychophysiological Effects of a Single, Short, and Moderately Bright Room Light Exposure on Mildly Depressed Geriatric Inpatients: A Pilot Study. Gerontology 2017, 63, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.M.; Kim, H.C.; Rhee, Y.; Youm, Y.; Kim, C.O. Association between Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations and Depressive Symptoms in an Older Korean Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 189, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-Y.; Yu, C.-P.; Wu, C.-D.; Pan, W.-C. The Effect of Leisure Activity Diversity and Exercise Time on the Prevention of Depression in the Middle-Aged and Elderly Residents of Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, D.; Gauvin, L.; Richard, L.; Kestens, Y.; Payette, H. Longitudinal Associations between Walking Frequency and Depressive Symptoms in Older Adults: Results from the VoisiNuAge Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 2072–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rantakokko, M.; Keskinen, K.E.; Kokko, K.; Portegijs, E. Nature Diversity and Well-Being in Old Age. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, W.; Wang, S.-M.; Yi, X. Regular Physical Activities and Related Factors among Middle-Aged and Older Adults in Jinan, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarran, C.; Albers, C.; Sachon, P.; Meesters, Y. Meteorological Analysis of Symptom Data for People with Seasonal Affective Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 257, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orstad, S.L.; Szuhany, K.; Tamura, K.; Thorpe, L.E.; Jay, M. Park Proximity and Use for Physical Activity among Urban Residents: Associations with Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, M.G.; Kross, E.; Krpan, K.M.; Askren, M.K.; Burson, A.; Deldin, P.J.; Kaplan, S.; Sherdell, L.; Gotlib, I.H.; Jonides, J. Interacting with Nature Improves Cognition and Affect for Individuals with Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 140, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Hart, J.E.; Banay, R.F.; Laden, F.; Signorello, L.B. Built Environment and Depression in Low-Income African Americans and Whites. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Mei, J.; You, J.; Miao, J.; Song, X.; Sun, W.; Lan, Y.; Qiu, X.; Zhu, Z. Sociodemographic Characteristics Associated with Adolescent Depression in Urban and Rural Areas of Hubei Province: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, B.; Chen, H.; Li, Z. Exploring the Linkage between Greenness Exposure and Depression among Chinese People: Mediating Roles of Physical Activity, Stress and Social Cohesion and Moderating Role of Urbanicity. Health Place 2019, 58, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, W.; Wang, S.-M.; Yi, X. A Cross Sectional Examination of the Relation Between Depression and Frequency of Leisure Time Physical Exercise among the Elderly in Jinan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.-B.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, H.-J.; Min, J.-Y. Parks and Green Areas and the Risk for Depression and Suicidal Indicators. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Cho, K.H.; Choi, J.; Shin, J.; Park, E.-C. The Impact of Sitting Time and Physical Activity on Major Depressive Disorder in South Korean Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.S.; Joung, K.H. Demographics and Health Profiles of Depressive Symptoms in Korean Older Adults. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Bang, M.; Wee, J.H.; Min, C.; Yoo, D.M.; Han, S.-M.; Kim, S.; Choi, H.G. Short- and Long-Term Exposure to Air Pollution and Lack of Sunlight Are Associated with an Increased Risk of Depression: A Nested Case-Control Study Using Meteorological Data and National Sample Cohort Data. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Ahn, Y.-S.; Koh, S.-B. The Longitudinal Effect of Leisure Time Physical Activity on Reduced Depressive Symptoms: The ARIRANG Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akers, A.; Barton, J.; Cossey, R.; Gainsford, P.; Griffin, M.; Micklewright, D. Visual Color Perception in Green Exercise: Positive Effects on Mood and Perceived Exertion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 46, 8661–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marselle, M.R.; Warber, S.L.; Irvine, K.N. Growing Resilience through Interaction with Nature: Can Group Walks in Nature Buffer the Effects of Stressful Life Events on Mental Health? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khouja, J.N.; Munafò, M.R.; Tilling, K.; Wiles, N.J.; Joinson, C.; Etchells, P.J.; John, A.; Hayes, F.M.; Gage, S.H.; Cornish, R.P. Is Screen Time Associated with Anxiety or Depression in Young People? Results from a UK Birth Cohort. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D.T.C.; Shanahan, D.F.; Hudson, H.L.; Fuller, R.A.; Anderson, K.; Hancock, S.; Gaston, K.J. Doses of Nearby Nature Simultaneously Associated with Multiple Health Benefits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.C.; Saxena, R.; Vetter, C.; Phillips, A.J.K.; Lane, J.M.; Cain, S.W. Time Spent in Outdoor Light Is Associated with Mood, Sleep, and Circadian Rhythm-Related Outcomes: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study in over 400,000 UK Biobank Participants. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murayama, Y.; Inoue, K.; Yamazaki, C.; Kameo, S.; Nakazawa, M.; Koyama, H. Association between Depressive State and Lifestyle Factors among Residents in a Rural Area in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2019, 249, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Effects of Walking in a Forest on Young Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, T.; Hamano, T.; Onoda, K.; Takeda, M.; Okuyama, K.; Yamasaki, M.; Isomura, M.; Nabika, T. Additive Effect of Physical Activity and Sedentary Time on Depressive Symptoms in Rural Japanese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Epidemiol. Jpn. Epidemiol. Assoc. 2019, 29, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Miura, T.; Taue, M.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Effect of Forest Walking on Autonomic Nervous System Activity in Middle-Aged Hypertensive Individuals: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 2687–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milaneschi, Y.; Hoogendijk, W.; Lips, P.; Heijboer, A.C.; Schoevers, R.; van Hemert, A.M.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Smit, J.H.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. The Association between Low Vitamin D and Depressive Disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.H.; Shanahan, D.F.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Lin, B.B.; Barber, E.; Franco, L.; Fuller, R.A. Is Nature Relatedness Associated with Better Mental and Physical Health? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Lin, B.B.; Dean, J.; Barber, E.; Fuller, R.A. Health Benefits from Nature Experiences Depend on Dose. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, S.; Smith, L.; Markovic, L.; Schuch, F.B.; Sadarangani, K.P.; Lopez Sanchez, G.F.; Lopez-Bueno, R.; Gil-Salmerón, A.; Rieder, A.; Tully, M.A.; et al. Associations between Physical Activity, Sitting Time, and Time Spent Outdoors with Mental Health during the First COVID-19 Lock Down in Austria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. High Sedentary Behaviour and Low Physical Activity Are Associated with Anxiety and Depression in Myanmar and Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; Aspinall, P. The Restorative Benefits of Walking in Urban and Rural Settings in Adults with Good and Poor Mental Health. Health Place 2011, 17, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Al-Anouti, F. Sun Exposure and Behavioral Activation for Hypovitaminosis D and Depression: A Controlled Pilot Study. Community Ment. Health J. 2018, 54, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.L.; Yadav, H. Depression among the Urban Poor in Peninsular Malaysia: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Safraj, S.; Tayyab, M.; Shivashankar, R.; Patel, S.A.; Narayanan, G.; Ajay, V.S.; Ali, M.K.; Narayan, K.V.; Tandon, N.; et al. Park Availability and Major Depression in Individuals with Chronic Conditions: Is There an Association in Urban India? Health Place 2017, 47, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, I.H.; Grynderup, M.B.; Dalsgaard, S.B.; Thomsen, J.F.; Hansen, Å.M.; Kærgaard, A.; Kærlev, L.; Mors, O.; Rugulies, R.; Mikkelsen, S.; et al. Does Outdoor Work during the Winter Season Protect against Depression and Mood Difficulties? Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2011, 37, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brown, M.J.; Jacobs, D.E. Residential Light and Risk for Depression and Falls: Results from the LARES Study of Eight European Cities. Public Health Rep. 2011, 126, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marselle, M.R.; Irvine, K.N.; Warber, S.L. Walking for Well-Being: Are Group Walks in Certain Types of Natural Environments Better for Well-Being than Group Walks in Urban Environments? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 5603–5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Sunlight and Vitamin D for Bone Health and Prevention of Autoimmune Diseases, Cancers, and Cardiovascular Disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1678S–1688S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccamo, D.; Ricca, S.; Currò, M.; Lentile, R. Health Risks of Hypovitaminosis D: A Review of New Molecular Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro Tomé, A.; Reig Cebriá, M.J.; González-Teruel, A.; Carbonell-Asíns, J.A.; Cañete Nicolás, C.; Hernández-Viadel, M. Efficacy of Vitamin D in the Treatment of Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2021, 49, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jorde, R.; Sneve, M.; Figenschau, Y.; Svartberg, J.; Waterloo, K. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on symptoms of depression in overweight and obese subjects: Randomized double blind trial. J. Intern. Med. 2008, 264, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, A.; Naderpoor, N.; de Courten, M.P.; de Courten, B. Vitamin D and symptoms of depression in overweight or obese adults: A cross-sectional study and randomized placebo-controlled trial. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 177, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, H.S.; Blower, D.; Cohen, M.L.; Czeisler, C.A.; Dinges, D.F.; Greenhouse, J.B.; Guo, F.; Hanowski, R.J.; Hartenbaum, N.P.; Krueger, G.P.; et al. Data and methods for studying commercial motor vehicle driver fatigue, highway safety and long-term driver health. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 126, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbarino, S.; Guglielmi, O.; Sannita, W.G.; Magnavita, N.; Lanteri, P. Sleep and Mental Health in Truck Drivers: Descriptive Review of the Current Evidence and Proposal of Strategies for Primary Prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapen, J.; Vancampfort, D.; Moriën, Y.; Marchal, Y. Exercise Therapy Improves Both Mental and Physical Health in Patients with Major Depression. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, N.; Epps, H.H. Relationship between Color and Emotion: A Study of College Students. Coll. Stud. J. 2014, 38, 396–405. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, K. Some Experimental Observations Concerning the Influence of Colors on the Function of the Organism. Occup. Ther. 1942, 21, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, G.; Stainer, D.S.; Sensky, T.E.; Moor, S.; Thompson, C. Phototherapy and Its Mechanisms of Action in Seasonal Affective Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 1988, 14, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, K.; Qian, Z.; Chen, P.; Lv, Y.; Yao, Y. Light Therapy in Non-Seasonal Depression: An Update Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, D.C.; Fogerson, P.M.; Lazzerini Ospri, L.; Thomsen, M.B.; Layne, R.M.; Severin, D.; Zhan, J.; Singer, J.H.; Kirkwood, A.; Zhao, H.; et al. Light Affects Mood and Learning through Distinct Retina-Brain Pathways. Cell 2018, 175, 71–84.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.W.; Hannibal, J.; Hagiwara, G.; Colas, D.; Ruppert, E.; Ruby, N.F.; Craig Heller, H.; Franken, P.; Bourgin, P. Melanopsin as a Sleep Modulator: Circadian Gating of the Direct Effects of Light on Sleep and Altered Sleep Homeostasis in Opn4−/− Mice. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, e1000125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.; Glenn, T.; Monteith, S.; Gottlieb, J.F.; Ritter, P.S.; Geddes, J.; Whybrow, P.C. The potential influence of LED lighting on mental illness. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 19, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, N.; Gusain, P.; Hayano, M.; Sugaya, T.; Tonegawa, N.; Hatanaka, Y.; Tamura, R.; Okuyama, K.; Osada, H.; Ban, N.; et al. Violet Light Modulates the Central Nervous System to Regulate Memory and Mood. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).