2. Background and Context

Zimbabwe’s media landscape is characterized by the presence of state-owned media, privately owned media, foreign media and social media whose functionality is largely facilitated by the internet and Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) among others.

Willems (

2011, p. 1) notes that in the early 2000s, the government of Zimbabwe began to restrict the operations of foreign and privately owned media which “published critical reports on government’s role in the growing economic and political crisis”. They managed to do this through enforcing media laws such as the Public Order and Security Act (POSA) which was gazetted into law in 2002, the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA) gazetted into law in 2002 (

Willems, 2010), the Broadcasting Services Act (BSA) which was introduced in 2001 and the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act of 2006 (

Willems, 2011), among others. Although privately owned media remained a significant source of information,

Willems (

2011) argues that because of restrictive media laws, most Zimbabweans were left with state-owned media as their primary source of information. For example,

Willems (

2010, p. 4) notes that “the national broadcaster, Zimbabwean Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC) dominated the airwaves and government did not allow any private radio or television station to start broadcasting” which limited the sources of information in the country.

As such, interpretations of the social, economic and political crises prevailing in Zimbabwe were largely understood based on the images portrayed by the state-controlled media (

Willems, 2011). In other words, debates on the Zimbabwean situation were largely shaped by the information disseminated by the state-controlled media and private dailies and weeklies. It is in this context that memes emerged as popular social media sites of challenging state media (

Willems, 2011). In other words, social media presented an alternative platform through which people could obtain different interpretations, expressed mostly in the form of jokes, about the Zimbabwean situation. Jokes or memes have been argued to speak to the economic, social and political issues playing out in the world around the users (

Willems, 2010). In the case of Zimbabwe, memes have been used to comment on crises like COVID-19 (

Msimanga et al., 2022;

Ndlovu, 2021) and politicians (

Makombe & Agbede, 2016). With regard to politics and politicians,

Shearlaw (

2016, p. 1) argues that “the sharing of memes and images mocking the country’s leaders is a new weapon against the regime”.

However, the sharing of such memes on social media platforms was criminalized by the government of Zimbabwe (

Gambanga, 2016a). According to

Musangi (

2012, p. 166), “it is a criminal offence to ridicule the president in Zimbabwe and it is punishable by law”. However, despite the restrictive legislation in Zimbabwe, people continue to share jokes on political figures, especially former President Robert Mugabe, former Minister of Higher and Tertiary Education Professor Jonathan Moyo, among others. The jokes circulate largely on social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp. Before WhatsApp, Facebook was extensively used as a political tool “something that most people will remember from the 2013 election period with the infamous

Baba Jukwa page” (

Gambanga, 2016b, p. 1). However,

Gambanga (

2016b, p. 1) argues that, of all the social media platforms that exist, WhatsApp offers a more interesting case for politics as it has a number of features such as end-to-end encryption (E2EE), making it “a prime tool for political use”. This raises questions in terms of what WhatsApp is and what makes it so effective in the Zimbabwean context?

WhatsApp, which is defined as a social media application and provides instant messaging abilities to people cheaply (

Madamombe, 2017), has, in recent times, become the leading social media platform used in Zimbabwe.

Khalil (

2025) argues that “WhatsApp accounts for nearly 44% of all mobile internet use”. It is used to “pass political messages on family, friends and church group chats” (

Financial Gazette, 2016, p. 1). Its popularity is largely attributed to the fact that it is affordable and accessible, unlike other social media platforms (

Seufert et al., 2016). Scholars such as

Lindquist (

2013) identify WhatsApp as being more accessible and cheaper when compared to sending an SMS using mobile networks.

Arguably, therefore, the popularity of WhatsApp among the research subjects of this study, that is, the youth, is due to its affordability. WhatsApp is frequently used by youths (

Salman & Saad, 2015) sharing information privately and in groups on the platform (

Seufert et al., 2016). To briefly define ‘youth’, the 2013 Zimbabwean constitution notes that youths are people between the ages of 15 and 35 (

Lindquist, 2013). Content shared on WhatsApp is likely to be consumed and largely used by youths and potentially plays a critical role in shaping their public opinions; hence, this study’s concern is with this content. To confirm this, the

Financial Gazette (

2016, p. 1) argues that “in Zimbabwe, the main users of social media are youths born after independence”. In the case of WhatsApp,

Chiridza et al. (

2016) found that there is high usage of the social media platform among the youth in Zimbabwe. As such, given that this research is focused on memes that circulate on WhatsApp, the youth are the most suitable population to derive participants from since they represent a section of the Zimbabwean population that uses WhatsApp more, compared to other age groups (

Chiridza et al., 2016).

Furthermore,

Gambanga (

2016b, p. 1) argues that besides WhatsApp being popular among Zimbabweans in general, and youths specifically, it also presents a number of features that make it a prime tool for use in political communication in restricted societies. These features include the end-to-end encryption (E2EE), which has enabled users to escape government control and censorship using media laws, which partly explains its popularity in restricted societies. Therefore, while the Zimbabwean government used laws such as the POSA of 2002 and the 2006 Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) (

Willems, 2011) in retaliation to mainstream media that was critical of the government and its leadership,

Chiridza et al. (

2016, p. 46) argue that social media was not subject to these laws. However,

Zulu (

2016, p. 1) notes that through acts such as shutting down networks that social media platforms relied on to function effectively, facilitating the turning of the Cyber Crime and Cyber Security bill into law and sometimes using the media laws meant for mainstream communication to regulate social media activities, the government widened “its crackdown on social media platforms such as Facebook and the messaging WhatsApp, arresting people for allegedly insulting and denigrating President Robert Mugabe”.

With regard to shutting down networks, following the

#ThisFlag campaign which mobilized Zimbabweans using social media sites, like WhatsApp, to march against the government,

Shearlaw (

2016, p. 1) notes that “there were reports of government attempts to shut down social media but citizens quickly started sharing details of VPN (Virtual Private Network) sites and encryption methods to get around the ban”. The Zimbabwean government also attempted to regulate social media through implementing the cybercrime law which would see people who abuse social media jailed for 10 years (

Bwititi, 2017). In terms of arrests, several people have been arrested for allegedly insulting and denigrating the former president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, and were charged using the same media laws which

Chiridza et al. (

2016) argue could not regulate social media activities. What these examples show is that the government has been working tirelessly to gain control of social media activities. However, despite the crackdown, what can be noted is that memes still play a major role in terms of confronting the political crisis in Zimbabwe (

Willems, 2011). Thus, due to the critical role played by memes in facilitating deliberation on the political, economic and social crisis in Zimbabwe, it becomes important to understand how they are being used by youths.

3. Memes and Social Media

The relationship between social media and memes cannot be ignored. Defining social media, Kaplan and Haenlein (2010), cited in

Hampton et al. (

2017, p. 7), argue that “social media is a broad, amorphous term that has been used to refer to those internet technologies built on a platform that allows for the creation and exchange of user-generated content”. Steenkamp and Hyde-Clarke (2014), cited in

Ariel and Avidar (

2015), consider social media as “a platform that facilitates information sharing and participation”. Their definition of social media concurs with that provided by

Lyons (

2017, p. 4), who defines social media as “applications that facilitate content creation, sharing, and social networking”.

Storsul (

2014, p. 17) argues that the main purpose of participating in social networking sites is “to socialize and check out what friends are doing”. What is common among these definitions is that they all understand social media as something that is social in the sense that it facilitates socialization. Social media platforms come with several characteristics which include participation, conversationality, connectedness, community and commonality, and openness (

Chan-Olmsted et al., 2013), all of which facilitate the creation and exchange of user-generated content. Examples of social media applications or social networking sites (SNSs), which facilitate the creation and exchange of user-generated content include Facebook, Twitter (

Miller et al., 2016), MySpace, Blogging, YouTube (

Rishel, 2011, p. 418) and WhatsApp (

Madamombe, 2017). Of these different social media platforms, WhatsApp is of interest to this study. Several memes are created and circulated on WhatsApp, thereby enhancing participation, interactivity and openness among individuals (

Lombard, 2014). This study, therefore, analyses how youths are encouraged to participate and interact on WhatsApp deliberations, especially after engaging with memes or jokes.

The word ‘meme’ was “coined by Richard Dawkins in 1976 to describe small units of cultural transformation that are analogous to genes” (

Shifman, 2014, p. 341). Dawkins developed the concept of memes “while trying to explain cultural transmission, human behaviour, cultural evolution and development of human society” (

Buchel, 2012, p. 17). The term sought to “describe the flow and flux of culture” (

Milner, 2012, p. 9) as it spreads from person to person (

Ding, 2015). Memes serve different purposes which include telling a story constructively while “some of them can even be outright harmful or even deadly” (

Buchel, 2012, p. 21). In general terms,

Zittrain (

2014, p. 389) argues that “a meme at its best exposes a truth about something and in its versatility allows that truth to be captured and applied in new situations”. To some, memes might appear useless, while to other people they might prove very effective in terms of deliberation.

Cortesi and Gasser (

2015, p. 1439) argue that “although memes can appear to be silly and irrelevant from an adult perspective, they can also function as a form of civic engagement, particularly, participation in the news ecosystem”.

This study is, however, focused on what is known as “internet memes”. Marshall (1995), cited in

Lombard (

2014, p. 1), notes that the internet is “an ideal medium for the spread, replication and storage of memes”. Some have argued that because of this, there has been a rise in what are termed ‘internet memes’. Internet memes are defined by Shifman (2013), cited in

Cortesi and Gasser (

2015, p. 1439), as “viral media objects that tend to be humorous imitations of some product or concept”. Memes are referred to as internet memes in digital culture, because they use web 2.0 technologies (

Adiga & Padmakumar, 2024, p. 264). The term “‘internet meme’ is used to refer to the dispersion of items, such as jokes, videos, images and websites from person to person through the internet” (

Shifman, 2014 cited in

Ding, 2015, p. 8). Several types of memes exist, and these include verbal memes like hashtags, audio memes like sound imitations and visual memes like photoshopped images (

Adiga & Padmakumar, 2024, p. 265).

Gorka (

2014) argues that memes are not only used to provoke debate but are also used to bring laughter. Key to this study, Gorka’s argument introduces the element of memes as jokes.

Siziba and Ncube (

2015, p. 518) argue that “internet memes are a subcategory of memes and take on different forms such as images, videos, websites, words, phrases, etc.” Given that memes are strongly linked with the internet, the relationship between social media and memes cannot be ignored. The power of internet memes lays in sharing, mutating and spreading (

Hardesty et al., 2019;

Moreno-Almeida, 2021).

Siziba and Ncube (

2015, p. 517) note that “internet memes have become a common term that is associated with the broad jargon of social media”. In other words, the sharing of memes is usually evident on social media sites “where users may share information by simply clicking on a button” (

Lombard, 2014, p. 29). Therefore, the communication of memes online through social media sites is similar to the communication of memes offline (

Lombard, 2014). As such, the study focuses on WhatsApp because it is a social media application through which most memes circulate (

Lombard, 2014).

Globally, several studies have been performed exploring internet memes (

Shifman, 2019;

Zappavigna, 2020).

Shifman (

2019, p. 46) argues that “the ongoing scholarly interest in internet memes reflects a prevalent perception that they actually matter”. In an analysis of “image macros”,

Zappavigna (

2020) argued that memes are important towards meaning making. Memes are used to promote deliberation on critical issues which can be social, economic or political (

Chandler, 2013). The deliberation promoted by memes can help to express some “significant economic, social and political power” (

Shifman, 2019, p. 47). It is this deliberation that this study is interested in. Humour is argued to be key to “meme culture” (

Ataci, 2023, p. 3160). Nyamnjoh (2005), as cited in

Chiumbu and Musemwa (

2012, p. 18), argues that the jokes and humour that are exchanged using new media technologies are being used creatively as “alternative spaces to debate issues of national importance”. A common feature of internet memes is “the manipulation of photos (photo shopping) and videos to create impressions, to have a certain effect, for example, intrigue, shock or humour, on the viewer”. As such, issues that are largely addressed through internet memes include “human interest issues or common issues like the love story, live experiences, education and even religion” (

Handayani et al., 2016, p. 334). Furthermore,

Heinrich-Boll-Stiftung (

2016, p. 7) notes that while satire in a liberal democracy has been used to critique state actors, “African satire has always criticized those who abuse power”. In authoritarian regimes such as Zimbabwe, memes “could be regarded as snapshots of political participation” (

Moreno-Almeida, 2021, p. 1562). For the youth, who are the major focus of this study,

Cortesi and Gasser (

2015) argue that memes are important as they present serious information in ways that are more engaging and interesting when compared to official information sources. What is important to this study is the acknowledgement that memes serve a very important purpose of encouraging deliberation on serious issues which can be political, economic or social, hence the need to study their usage in concrete situations.

Several studies have explored the relationship between memes, social media and political participation (

Siziba & Ncube, 2015;

Kasirye, 2019;

Soh, 2020;

Moreno-Almeida, 2021;

Halversen & Weeks, 2023;

Ahmed & Masood, 2024;

McSwiney & Vaughan, 2024;

AlAfnan, 2025). According to

Ahmed and Masood (

2024, p. 3), “the relationship between political social media use and political participation may be intricately linked with one’s exposure to political memes”. In their study on how memes were used in Singapore during elections,

Soh (

2020) concluded that memes are used to communicate to the government itself. This essentially means that memes “are a tool of political participation” (

Kasirye, 2019, p. 45).

McLoughlin and Southern (

2021, p. 60) also concluded that memes are a way through which citizens participate in political activities. In the case of Zimbabwe, several studies have looked into memes and their uses, and these include

Willems (

2011),

Chiumbu and Musemwa (

2012),

Siziba and Ncube (

2015),

Makombe and Agbede (

2016),

Mpofu (

2021),

Msimanga et al. (

2022), and

Tivenga (

2022), among others. As

Willems (

2011, p. 410) argues, in the context of the restrictive media environment in Zimbabwe, “political jokes and rumour emerged as important social movement media, challenging state-controlled media interpretations of the crisis”. In other words, memes became very useful in facilitating deliberations on the economic, social and political crisis in Zimbabwe. Jokes have been strategically used by Zimbabweans to deliberate on political issues (

Chiumbu & Musemwa, 2012) such as police brutality (

Tivenga, 2022), former president Robert Mugabe (

Makombe & Agbede, 2016) and COVID-19 (

Msimanga et al., 2021) without any penalties. This study contributes to this extant literature by looking at how memes, usually considered trivial, present a public sphere through which youths engage in rational debates on critical issues.

4. Theory

This study is underpinned by two theories that guide this study, namely Habermas’s public sphere concept and Bakhtin’s theory of carnival. Habermas (1974), cited in

Khan et al. (

2011, p. 1), defines the public sphere as “a sphere which mediates between society and state, in which the public organizes itself into a bearer of public opinion”. In his definition of this sphere,

McQuail (

2005, p. 181) states that the ideal “public sphere refers to a notional space which provides a more or less autonomous and open arena or forum for public debate”. Mass media are themselves identified as a public sphere in their own right. Mass media in this case can include television, radio and newspapers (

Nieminen, 2004). The media, as a public sphere, are normatively expected to be deliberative and pluralist (

Benson, 2009). The internet and its associate technologies such as social media arguably extend Habermas’s notion of the public sphere. In this study, WhatsApp is taken as part of the mediated public sphere whose form potentially instantiates Habermas’s conception of the public sphere. For example, as some have pointed out, WhatsApp is decentralized and open and free from government control and censorship, as evidenced through the end-to-end encryption which prevents any third parties from spying on chats (

Gambanga, 2016b). Habermas’s theory of the public sphere is critical to this study, since memes arguably extend the notion of a public sphere through their promotion of free and inclusive deliberation of socio-political and economic issues affecting particular societies (

Willems, 2010). It is on this premise that the public sphere theory informs this study, as it is useful in the assessment of how WhatsApp enables deliberation on politics through memes. Since jokes can be seen as extending Habermas’s notion of a public sphere through their promotion of free and inclusive deliberation of socio-political and economic issues affecting particular societies, it is important to assess how this works out in concrete situations, particularly regarding the often-marginalized demographic of the youth.

The second theory that underpins this study is Bakhtin’s theory of the carnivalesque. According to

Fallis (

2014, p. 5) “Mikhail Bakhtin coined the term ‘carnivalesque’ in reference to a literary mode that uses humour and profanity to upend, criticize, but then ultimately reify what is culturally dominant within a society”. Humour, according to

Ataci (

2023) has become one way through which young people “entangle the personal, public and political”. The term ‘carnivalesque’ refers to not only the general carnival but to “the varied popular–festive life of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance” (

Bakhtin, 1984, p. 218). Bakhtin’s theory of the carnival argues that carnivals offer a sense of liberation from official and serious culture, temporarily abolish inequalities, normalize ideals that are deemed impossible in everyday life, create a second world and lower all that is deemed high (

Bakhtin, 1984) through the celebration of “profane language as well as primitive bodily functions” (

Fallis, 2014, p. 5).

Taylor (

1995) identified the three aspects of carnivalesque practices as grotesque imagery, laughter and the marketplace. Grotesque imagery refers to a representation of “an alternative to the symbolism and ideology of officialdom” (

Taylor, 1995, p. 21) and it focuses on the “body’s orifices” (

Taylor, 1995, p. 20). The main focus of the grotesque is transferring that which is considered high and ideal “to the material level, to the sphere of earth and body” (

Bakhtin, 1984, p. 19). As for laughter,

Taylor (

1995) argues that Bakhtin ascribed it a number of qualities which include overcoming fear, universal quality, freedom and that it enjoyed an epistemological status. According to

Bakhtin (

1984, p. 66):

Laughter has a deep philosophical meaning, it is one of the essential forms of the truth concerning the world as a whole, concerning history and man; it is a peculiar point of view relative to the world; the world is seen anew, no less (and perhaps more) profoundly than when seen from the serious standpoint.

According to

Taylor (

1995), both grotesque imagery and laughter take place in the marketplace, which is the last aspect of the carnivalesque. In

Bakhtin’s (

1984, p. 154) account, “the marketplace was the centre of all that is unofficial”, which in this case includes grotesque imagery and laughter. In this sense, WhatsApp can be viewed as the marketplace where unofficial aspects such as laughter are analyzed in the form of memes which circulate and give vent to unofficial expression. Memes have been analyzed as carnivalesque by scholars such as

Denisova (

2019) and as grotesque by scholars such as

Galip (

2021) and

Moreno-Almeida (

2021). Bakhtin’s theory of the carnival is important to this study as it provides a framework for understanding how comic expressions function politically, hence, making it useful since this study explores how youths use the memes they engage with on WhatsApp. It “helps to further connect artful political communication, media activism and internet memes” (

Denisova, 2019, p. 19).

The two theories are “rarely considered together” (

Nielsen, 1995, p. 803), precisely because they are from different foundations. Outlining the differences between the two theories,

Gardiner (

2004, p. 30) argues that:

Whereas Habermas seeks to delineate sharply between particular realms of social activity and forms of discourse—between, for instance, public and private, state and public sphere, reason and non-reason, ethics and esthetics—Bakhtin problematizes such demarcations, sees them as fluid, permeable and always contested, and alerts us to the power relations that are involved in any such exercise of boundary maintenance.

Gardiner (

2004, p. 39) argues that Habermas’ concept of the public sphere, failed “to grasp adequately the significance of the embodied, situational and dialogic elements of everyday human life”. Some of these dialogic elements include humour. Bakhtin considered these elements as “a crucial resource through which the popular masses can retain a degree of autonomy from the forces of sociocultural homogenization and centralisation” (

Gardiner, 2004, p. 39). As such, these two concepts complement each other when it comes to the understanding of memes and meme usage. It is crucial to use Bakhtin’s concept of the carnivalesque to make sense of how humour is used in a public sphere to challenge authority. Some of the few studies that have used the two theories in one theoretical framework include

Msimanga et al. (

2022), who used the two theories to explore the use of memes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Methods

This study used a qualitative research methodology to analyze the political uses of memes circulating on WhatsApp by the youth of Bulawayo. For the purpose of making the study feasible in terms of access to participants, focus is put only on students from higher and tertiary institutions such as the National University of Science and Technology (NUST), Hillside Teachers College (HTC), Lupane State University (LSU) and Bulawayo Polytechnic. Furthermore, the researcher also used youths from religious institutions, with the participants specifically being drawn from both traditional churches, namely the Seventh Day Adventist, and Roman Catholic and contemporary churches, namely the Twelve Apostle and Word of Life Ministries. It should be noted that the diversity of these institutions is meant to ensure a diversity of opinions and comments (

Moriarty, 2011). The tertiary institutions are selected because mobile and social media penetration amongst higher and tertiary education students is high (

Dlamini et al., 2015). Religious institutions were selected to understand how religious background influences how youths, who do not come across as political, engage with the memes they encounter with on WhatsApp. As such, this diversity in terms of institutions and actual participants results in the diversity of views and opinions among the youths regarding their use of the political jokes that they engage with on WhatsApp (

Moriarty, 2011). Educational and religious institutions were selected using purposive sampling. The researcher arrived at these samples after considering that their population is largely made up of youths, who are the target population of this study. With regard to individual participants, purposive sampling involved “identifying and selecting individuals that are especially knowledgeable about a phenomenon of interest” (Cresswell & Clark, 2011 cited in

Palinkas et al., 2015, p. 2) which is Zimbabwean memes or jokes that circulate on WhatsApp. Beyond the youth, this study is about the political use of memes in authoritarian contexts.

Qualitative research is an approach which seeks an in-depth understanding of why and how things are in the social world (

Hancock et al., 2009). Semi-structured interviews were conducted over a period of 1 month with purposefully selected youths from Bulawayo’s tertiary and religious institutions. It should be noted that for qualitative studies, it is difficult to ascertain the number of interviews required to gather enough data (

Edwards & Holland, 2013). As such, the number of interviews for this study was determined by the fact that the researcher had only a month to collect data. However, based on the argument that “data theme saturation is achieved after 12 interviews” (

Edwards & Holland, 2013, p. 66), fourteen interviews with Bulawayo youths were performed in this study (See

Table 1). To capture the interview, the researcher took down notes to allow for the identification of important points and used a tape recorder to provide a complete and accurate record of the responses by participants (

Muswazi & Nhamo, 2013). These tools enabled the researcher to accurately capture participant responses and helped to avoid any misinterpretations. In a broader sense, the interviews afforded the researcher an opportunity to acquire perceptions of youths regarding how they use memes for political debates on important issues in Zimbabwe. A focus group discussion with participants drawn from the interviewees was conducted. The total number of participants in the focus group discussion for this study was placed at 5. Given that “purposive sampling is a commonly used procedure for focus group interviews” (

Mafuwane, 2012, p. 85), the 5 participants were purposefully selected. The group discussion participants were purposefully selected from the interviewees after the researcher noticed they were very knowledgeable about the phenomenon under study, that is, memes. Hence, their inputs in the focus group discussions are used to interpret the qualitative results obtained from the interviews. The FGD enabled us to rely on the naturalness and freedom created when different members of the group discussed with each other, so that data are generated by the interactions (

Moriarty, 2011).

The major ethical consideration in this study is minimized harm to both the subjects of satire and the research participants. As

Benatar (

2014, p. 26) argues, when it comes to humour, ethical questions tend to arise in categories which include blasphemous humour and humour about people’s personal attributes such as “big ears or noses, their short or tall stature, or their mental or physical disabilities”. Humour is argued to indirectly cause harm (

Benatar, 2014) through acts such as “offence, embarrassment, shock, disgust and the feeling of being demeaned or insulted” (

Benatar, 2014, p. 33). To minimize harm for the participants, the researcher made it known to the participants that their identities could be made anonymous. Furthermore, the researcher sought the consent of the participants before they participated in both focus group discussions and in-depth interviews (

Orb et al., 2001). Regarding consent, each participant was fully informed about the nature of the study. Upon agreeing to participate, participants signed a form to show that they agreed. To ensure anonymity, the signed consent forms were safely kept so that they did not fall into the wrong hands. Furthermore, the researcher assured the participants that the discussions which were being recorded would be kept safely and treated in strict confidence, since some memes are very sensitive and thus made some individuals uncomfortable talking about them.

6. WhatsApp as a Deliberative Platform

WhatsApp has been argued to promote deliberation through several features which

Chan-Olmsted et al. (

2013) define in terms of participation, conversationality, connectedness, community and commonality. As noted before by

Moreno-Almeida (

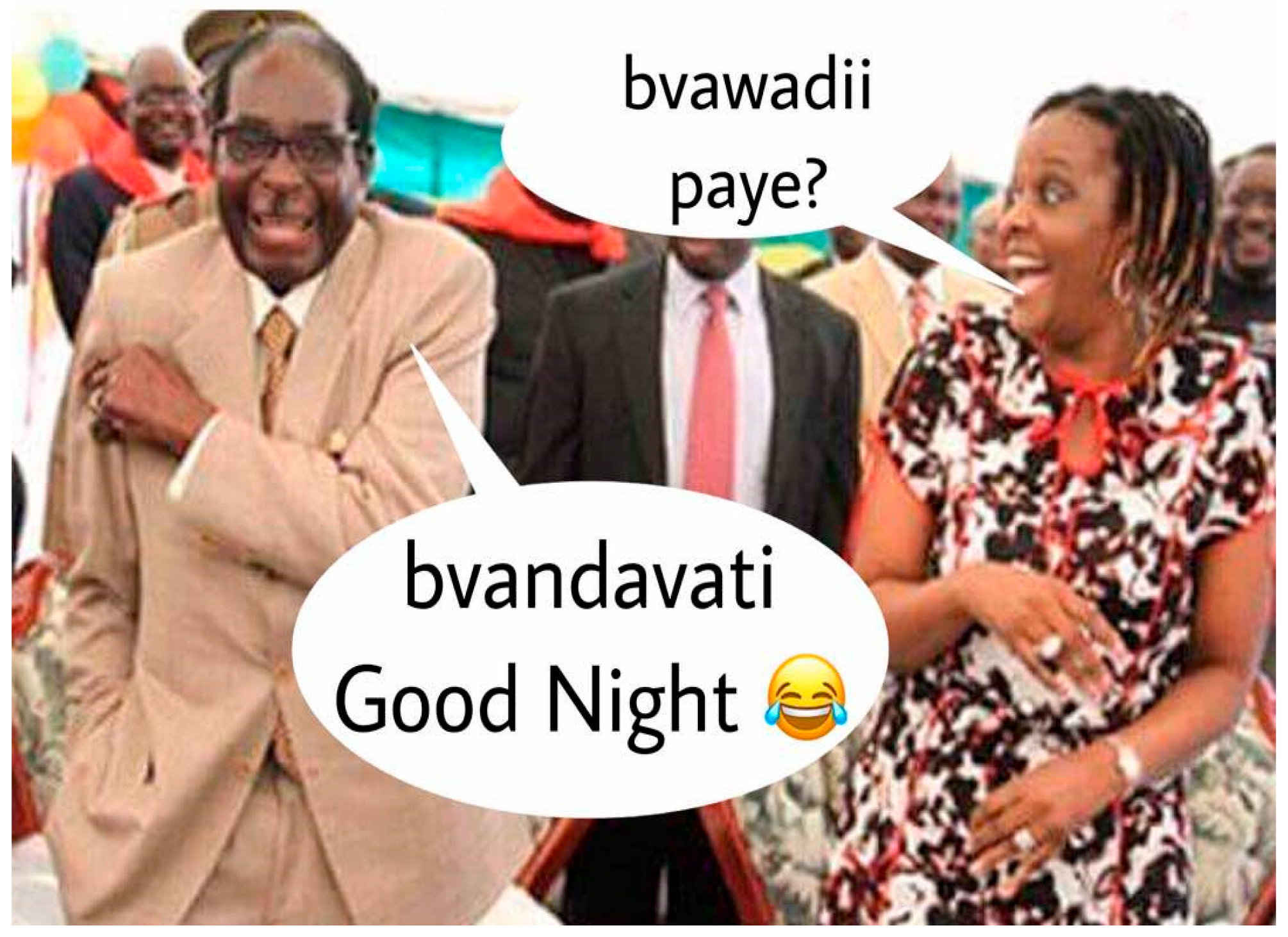

2021), memes are “snapshots of participation”. The findings from this study show that memes (see

Figure 1) shared through WhatsApp enable young people to participate and deliberate on serious issues. Some interviewees attributed their frequent usage of WhatsApp to the sharing feature offered by the platform. All participants noted that they share jokes, ten share academic information, nine share news and church material and eight share music. Participant 10 argued that the sharing feature enables him to take part in social debates, including academic discussions. He noted that WhatsApp has enabled him to share documents for academic purposes, which he said was convenient when compared to physically travelling to obtain access to a specific document. Participant 8 said, upon receiving a meme, “

I put it on my WhatsApp status and people were asking if I could share it with them but because of data costs I could only share with one or two, but with the network we have these days you can share with as many people as possible”. Evidently for these participants, WhatsApp facilitates the sharing of information (

Ariel & Avidar, 2015). This finding aligns with findings by

Shifman (

2019, 54) who argued one of the communicative values of memes is the freedom of information which is aided by “the rise in sharing as a constitutive act”. For memes, the sharing feature is very important. As noted before, internet memes “occur through activities such as sharing” (

Adiga & Padmakumar, 2024, 264) and sharing is “a key feature of participatory digital cultures” (

Newton et al., 2022, 1).

Another aspect that the interviewees identified as encouraging them to frequently use WhatsApp and actively participate in social debates is its end-to-end encryption (E2EE) facility. Participant 14 highlighted the effectiveness of the feature in enabling participation in social debates when she said:

The E2EE has really given me and other people the freedom of knowing that discussions are not spied on.

She went further to note that, given that in the past there were some issues that were difficult to debate about, such as politics, specifically commenting on former President Robert Mugabe, the E2EE facility gives her freedom to actively and confidently participate in social debates. The structural dimension of analyzing the public sphere “directs our attention to the way in which the communicative spaces relevant for democracy are broadly configured” through focusing on issues to do with “freedom of speech, access and the dynamic of inclusion/exclusion” (

Dahlgren, 2005, p. 149). In terms of the structural dimension of the public sphere, the findings of this study suggest that social media, WhatsApp specifically, functions as a form of the “online public sphere” (

Semaan et al., 2014) that is accessible, inclusive and allows for freedom of speech.

But given Zimbabwe’s peculiar history of intimidation and surveillance by the state, limited independent assertiveness is also evident in some respondents who expressed apprehension about participation. One participant during the focus group discussion hinted on the polarized nature of WhatsApp and how it affects participation in deliberations. The participant, responding to another participant who said he takes action beyond social media, said “

I share these memes with the same people every time and it ends there”. These concerns resonate with

Halpern (

2017, p. 3969) who argues that social media does not promote democratic deliberation because it consist of “mainly individuals with similar views who reinforce each other’s viewpoints”. However, as indicated by most respondents, assertive and independent communication on WhatsApp is enabled by features such as end-to-end encryption, which prevents any third parties from spying on their communication activities (

Gambanga, 2016b). Participants in this study argued that WhatsApp functionalities such as chat groups, the sharing feature and the E2EE feature “facilitate deliberation between more people” (

Storsul, 2014, p. 21). WhatsApp is therefore evidently a platform where participation in deliberations is not influenced by state or corporate power, a condition which

Dahlberg (

2004) identifies as essential for a functional public sphere. As such, WhatsApp provides a potentially ideal public sphere as it promotes unfettered deliberation.

The E2EE facility therefore provides youths the freedom and confidence to engage with sensitive memes, thereby giving them liberation from the constraints of official serious culture (

Bakhtin, 1984). Participant 14 further argued that the feature pushes her to participate “

as there is no fear of victimization”. In the case of Zimbabwe, there are laws such as the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act which criminalizes criticism of the president. As shown from the findings of this study, such laws have inculcated a culture of fear among people. As such, Zimbabweans in general, and youths specifically, have taken advantage of the E2EE feature to participate in political discussions and debates, since it makes it impossible for third parties to access their messages (

Gambanga, 2016b). It is through these features that WhatsApp enables participation, conversationality, connectedness, a sense of community and commonality (

Chan-Olmsted et al., 2013).

Participants highlighted that on WhatsApp, they deliberate on political, economic and social issues. With regard to political deliberations, most youths felt WhatsApp has opened “the door for all to have a voice and participate in a democratic fashion, including people in repressive countries” (

Amedie, 2015, p. 3). For example, as Participant 12 said:

I am now able to communicate my personal views about the people I feared the most, I think political debates are more fun.

In other words, considering the repressive nature of the Zimbabwean political setup, as exhibited by laws that criminalize expression on social media (

Gambanga, 2016a), participants in this study believe that social media has largely provided the freedom for one to freely comment on sensitive issues that were previously scary to participate in. Social media has provided the opportunity for youths to criticize the official culture (

Bakhtin, 1984). As for economical deliberations, a considerable number of interviewees expressed interest in economic debates because they feel the state of the economy has an impact on their future, hence, making their participation in economic debates critical. Participant 8 highlighted that he is interested in debates on the economy because he feels he has “

something to contribute to the economy than politics and the social”. He argued that by participating in economic debates, he “

could get more ideas on how to improve the national economy”. Another interviewee, participant 14, said that she is more interested in social debates about general life issues such as relationships and survival tactics in life. These findings show that although debates that take place on WhatsApp largely centre on political issues, there are also discussions on non-political issues, such as those related to academic subjects and relationships. As such, social media in general and WhatsApp specifically can be argued to be serving as a deliberative platform for political, economic and social issues.

7. Memes as Catalysts of Debate and Action

This study shows that memes are used by youths to engage in debates on serious issues. Furthermore, the participants highlighted that they engage in some action after encountering memes. The action taken is, however, limited to two spheres, namely the social media sphere and physical sphere. Within the social media sphere, the first action that most participants argued they take is laughing. Participants during the focus group discussions argued that laughing gives them some sense of freedom of having challenged a powerful person that would have been joked about, for example, the president of Zimbabwe or a sensitive issue that would have been presented as a meme, for example, politics. Laughter, according to

Ataci (

2023, p. 3158) provides a space for young people to explore “youth imaginaries as well as young people’s experience of, and opinions and concerns about everyday life”. One participant in the focus group discussions said:

When I received memes after the retirement of Robert Mugabe, I laughed and felt happy. We started talking about it with my friends and we felt free.

Therefore, the laughing that is induced by memes is seen as liberating and a way of challenging authority. As such, the findings in this study reveal that laughing is the first action taken upon engagement with memes, which is important since laughter, according to

Bakhtin (

1981), grants people freedom and the power to overcome fear. In Bakhtin’s theory of the carnivalesque, hierarchical ranks, privileges, norms and prohibitions are suspended (

Bakhtin, 1984). Most participants in this study noted that whenever they receive memes, they laugh. When participants laugh at memes about political figures, the low (ordinary people) become high while the high (political figures) become low (

Fitz-Henry, 2016). Furthermore, participants highlighted that they feel a sense of freedom after laughing at the memes they encounter on WhatsApp. According to

Tivenga (

2022, p. 495), laughter not only offers comic relief, but it also empowers people. This conviviality, which undergirds deliberative activity, may be difficult to express in real-life situations in restricted societies such as Zimbabwe, hence, their importance. For example, one participant argued that laughing gives her some sense of freedom and satisfaction for having challenged a powerful person that would have been joked about. By so doing, she would have lowered that which is deemed high and beyond rebuke (

Bakhtin, 1984). Another participant noted that after laughing, she “

felt free”. Arguably, this is important as it can potentially open up avenues for challenging official malfeasance and, simultaneously, valorize ordinary people. Therefore, political memes circulating on WhatsApp in Zimbabwe enable the youth to freely engage with critical political issues without fear of political intimidation and in a register than allows free and incisive criticism. This register includes the use of language that has irony, hyperboles and sarcasm (

AlAfnan, 2025).

The second action that youths take after laughing is that of sharing with the intention of stimulating debate among people.

Margetts et al. (

2019) refers to the aspect of sharing on social media as one of the “tiny acts of participation” in debates. One participant said that after laughing, she shares the memes and after sharing, she analyses responses and through that analysis she is able to see both the negative and positive aspects of a certain issue. Another participant in the focus group discussion said that:

After receiving memes, I send to people and we discuss. From these discussions, I get to see another point of view that I was not aware of. My eyes are opened. So, as we are heading towards elections, people who participate in these discussions are changed in terms of who they are deciding to vote for.

She said she uses the debates as a way of expressing her views and she tries to convince people to share those views. Another participant added that through sharing, they are able to analyze a meme based on the responses that they receive from other people. This analysis is performed through deliberation with friends on WhatsApp. Although Habermas emphasizes the importance of rational debates in the news and in politics, other informal talks such as those occasioned by memes are “the fundamental basis of rational public deliberation” (Kim & Kim, 2008 cited in

Huntington, 2017, p. 26). According to

Huntington (

2017, p. 27), “everyday talk includes not only discussions of political talks but also the creation and distribution of political content, including memes”. Another participant said that “

when a meme is shared, it eventually reaches those in official authority and my mission will be accomplished through laughing and sharing that meme”. Sharing is considered a constitutive act that is vital towards the spreading of information (

Shifman, 2019). With reference to why sharing is limited to social media, one participant said that “

it’s difficult to take action outside of social media because anything is possible since there are a lot of officers in plain clothes”. In other words, those that do not share memes, do so because of the fear of what might happen.

In terms of the interactional dimension of the public sphere, these findings show that WhatsApp enables citizens to deliberate and “engage in talk with each other” (

Dahlgren, 2005, p. 149). According to

Dahlgren (

2005) interactive processes can be analyzed in terms of two aspects. First, one has to consider “the citizen’s encounter with the media, the communicative processes of making sense, interpreting and using the output” (

Dahlgren, 2005, p. 149). Second, one has to consider interactions “between citizens themselves, which can include anything from two-person conversations to large meetings” (

Dahlgren, 2005, p. 149). With reference to the first aspect, most of the participants in the study argued that when they receive memes, they share with their contacts on WhatsApp and deliberate on them in order to come up with their own interpretations which, in some cases, inform how they act. For some participants, memes function as sources of information, while for others they provide a sense comic relief. Furthermore, it emerged that informational memes tended to also form the basis for subsequent deliberative and social activities.

This study also found that as a third action, some youths confront those in leadership positions using social media platforms. The debates that take place on WhatsApp are extended to other social media platforms such as Twitter, where the youths engage people in leadership positions. For example, one participant said the following:

We have got a WhatsApp group for risk management and actuarial society. In that group, a person sent a political meme in the form of text about students paying fees while on attachment. Some of the guys in the group started giving answers and after that, the issue was taken, and the secretary wrote a paper addressing it to president Mnangagwa and sent it to Twitter and tagged Mnangagwa.

This shows that youths do engage in action, although it is largely limited to social media platforms. Youths utilize Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to take action which they cannot take physically.

However, one respondent noted how polarization around different issues under discussion affects participation in ongoing deliberations. In some cases, it discourages participants from exploring issues beyond simply sharing the memes within familiar and safe networks. In her own words, she notes, “

I share these memes with the same people every time and it ends there”. Her concern is consistent with

Halpern’s (

2017, p. 3969) observation that social media limits democratic deliberation because it consists of “mainly individuals with similar views who reinforce each other’s viewpoints”. This is also confirmed by

Halversen and Weeks (

2023, p. 2) who argue that “social media users who frequently circulate political memes may also be more politically partisan”. This, therefore, shows that in some respects, social media arguably fall short of the ideal public sphere, as conceived by Habermas. Also, as

Baek et al. (

2011) argue that while discussions on social media platforms encourage the participation of poor individuals, some of these individuals might not participate in the discussions because of the digital divide. The digital divide is defined as “the gap between people who do and do not have access to forms of information and communication technology” (

Van Dijk, 2017, p. 1). Most participants in this study noted that they prefer to engage with image memes rather than videos because of data costs. The digital divide, in this case, is evident in the gap between those who can afford to engage with video memes and those who cannot. As one respondent indicated, although videos are attractive, they are “

expensive to download”. For that reason, the participant preferred images and, as such, participated in debates on issues that were presented through picture memes rather than video memes. Most of the participants that prefer video memes have access to free Wi-Fi at work or school. These findings demonstrate that to some extent, the inclusivity of WhatsApp as a form of the public sphere is questionable on the basis of limits imposed by cost, which in turn limits the horizon of active participation by the youth in public debates on social media. This shows the pervasive, negative influence of economic factors on public discourse, even among the most promising discursive platforms such as WhatsApp (

Fuchs, 2014).

While some youths limit their actions to social media activities, some extend their actions into the physical sphere where they engage with their peers face to face and try to convince them to take a certain form of action. This supports the argument that “online participation can boost offline engagement” (

McLoughlin & Southern, 2021, p. 63). A participant in the focus group discussion said that he utilizes his position as the chairman of a certain political party to take the debates he has on WhatsApp over to the people at political rallies. He said, “

I go on the ground, talk to the people from different constituencies, tell them the good part of my party and the bad part of ZANU PF”. In other words, he uses his encounter with memes to challenge other political parties, especially the ruling party. This confirms the findings of

Johann (

2022), who concluded that the sharing of internet memes online can be linked to offline political participation. This shows that while some of these deliberations are limited to social media groups because of fear, other deliberations extend beyond social media, with some youths becoming politically active in the offline world. This is why scholars such as

Frazer and Carlson (

2017) argue that memes are a form of political subversion. Since memes motivate the participant to challenge the ruling ZANU PF party’s leadership, he is seen as exercising some form of political subversion. The findings presented and analyzed above speak a lot to Habermas’s ideas of the public sphere and Bakhtin’s theory of the carnivalesque.

This study also shows that memes facilitate rational debates on serious and important issues. Habermas’s theory of the public sphere has been criticized for its “emphasis on rational public debate” (

Huntington, 2017, p. 24) at the expense of debate in everyday talk. For instance, Habermas (1974), cited in

Nieminen (

2004), argues that ideally, rational debate takes place through content such as the news. This view excludes other sorts of interactive debates, through informal methods like memes, which play out on social media despite their importance to those engaged in such debates. One participant in this study noted that he is not a fan of the news and as such he obtains information about critical issues in Zimbabwe through memes. In other words, for some, news shared via official platforms like the radio, television and newspapers is too serious. Memes, on the other hand, provide information about critical issues such as the economy and politics, in an informal way that appeals to the young generation. This shows that a functional public sphere is not only made up of rational debates, but is also characterized by informal, banal and seemingly trivial debates, such as those occasioned by memes circulating on social media. However, it is not always the case that banal forms of deliberation enable ordinary people to freely challenge and question official culture, as argued by Bakhtin. Most participants in this study highlighted that their engagement and use of memes is limited by the fear of victimization. The fear expressed by most participants shows that laughter does not necessarily offer liberation from serious culture. In fact, its experience itself may indeed provide the very ground for persecution. Also, although

Bakhtin (

1984) argues that carnival activities, which include the engagement with memes, provide a sense of liberation from the official serious culture, this study shows that instead, people remain seized by the instruments of oppression wielded by those in authority. For example, one participant highlighted that upon engaging with a meme on WhatsApp, they do not take further action because of fear, given the Zimbabwean government’s history of repression.