Local Voices, Global Circulation: Women’s Agency, Sorority and Glocalisation in K-Pop Demon Hunters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Methodology

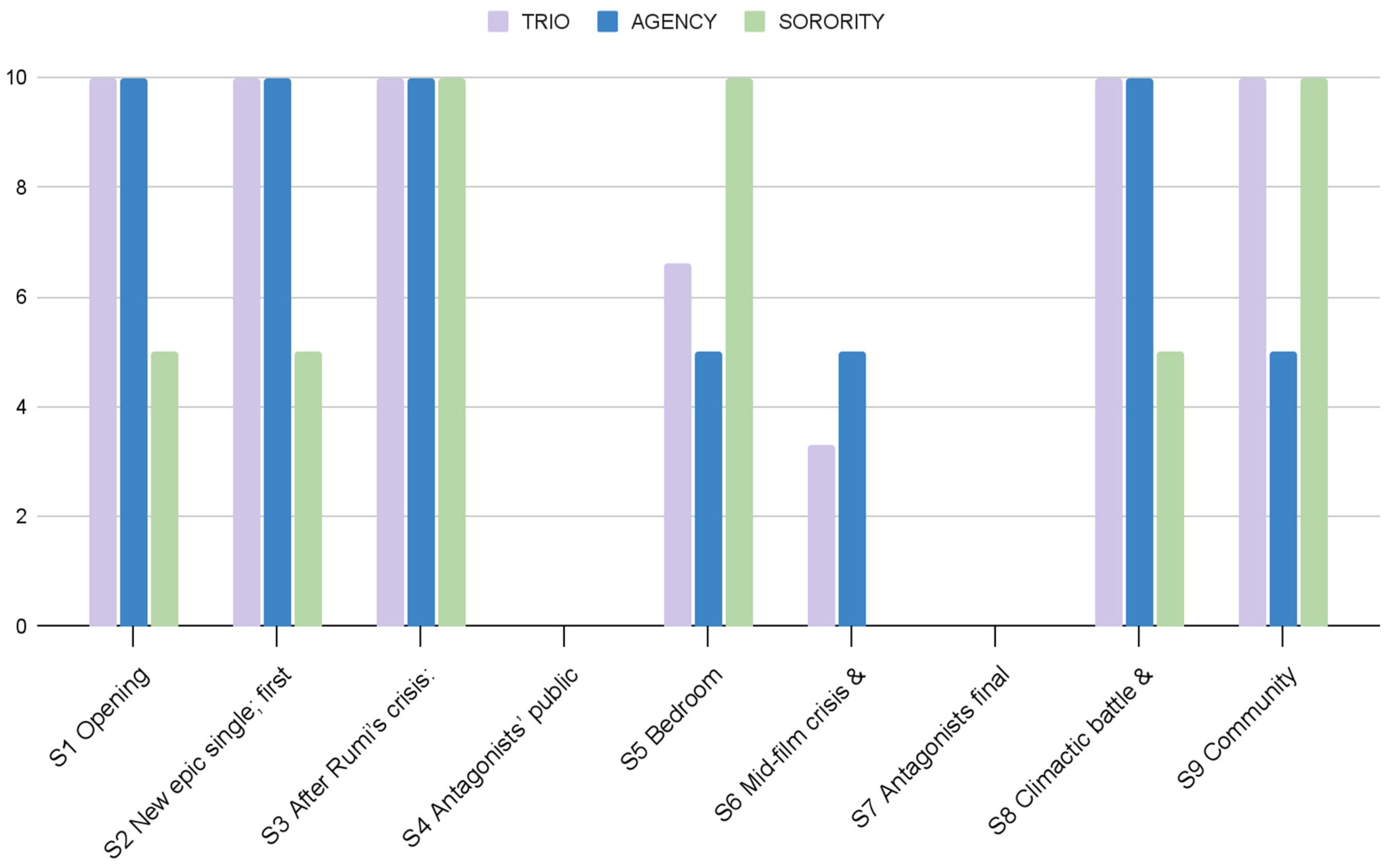

Agency = decision ownership and/or strategic competence legible via blocking/continuity.Sorority = care/repair and alignment that sustains collective action (dialogic or kinetic).Gendered alignment = co-presence and shared agency of women protagonists (TRIO ≥ 2; AGENCY ≥ 1; SORORITY ≥ 1).Body framing = full-body competence (non-fragmenting) vs. fragmenting display.Choreo–camera = edits/moves that exalt synchrony.Colour shift = salient palette/light transition linked to empowerment/jeopardy beats.

4. Results

4.1. Women’s Agency and Sorority

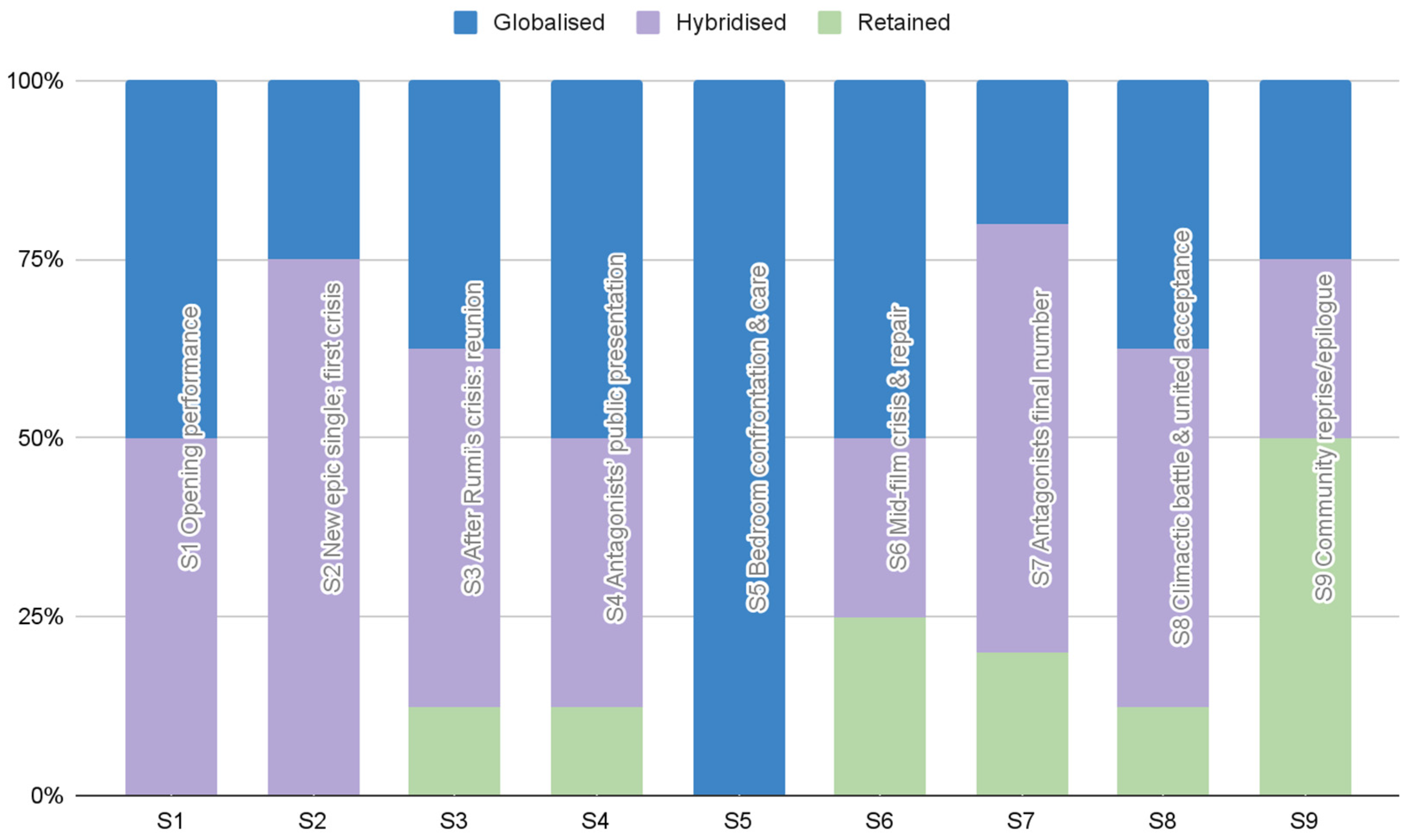

4.2. Korean Cultural Codes

4.3. Songs and Language (KR/EN) as Legibility Design

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Gender Media Studies | GMS |

| Research Question | RQ |

| English/Korean (language codes in lyric analysis) | EN/KR |

| Retained/Hybridised/Globalised (cultural-codes matrix) | R/H/G |

| Focal scenes (scene labels) | S1–S9 |

| TRIO_ONSCREEN (co-presence of the three protagonists) | TRIO |

| Decision ownership/strategic competence (scene code) | AGENCY |

| Care/repair and collective alignment (scene code) | SORORITY |

| Full-body competence vs. fragmenting display (scene code) | BODY_FRAMING |

| Choreography–camera reinforcement (scene code) | CHOREO_CAMERA |

| Palette/light transition tied to narrative beats (scene code) | COLOUR_SHIFT |

Appendix A. Reach & Circulation

| Link | Source (Publisher) | Region/Scope | Date (ISO) | Metric/Claim | # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (https://www.netflix.com/title/81498621 (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Netflix | Global | 18 October 2025 | Netflix title page (official programme page, synopsis, cast) | R1 |

| (https://people.com/kpop-demon-hunters-most-watched-movie-ever-netflix-11798152 (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Reporting creators; notes Netflix’s peak popularity | US | 17 October 2025 | “Most-watched on Netflix” framing in major entertainment press (context article) | R2 |

| (https://www.netflix.com/tudum/articles/kpop-demon-hunters-halloween-sing-along (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Netflix Tudum | Global (event) | 15 October 2025 | Halloween Sing-Along theatrical re-release announcement (official) | R3 |

| (https://elpais.com/cultura/2025-10-17/las-guerreras-k-pop-la-pelicula-animada-mas-vista-de-la-historia-de-netflix-vuelve-a-los-cines-en-version-sing-along.html (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | El País (Cultura) | Spain | 17 October 2025 | Spain press: theatrical Sing-Along limited run; cites “most watched in Netflix history” + soundtrack traction | R4 |

| (https://as.com/meristation/cine/las-guerreras-k-pop-llegan-a-la-gran-pantalla-podras-cantas-con-huntrx-en-cines-por-tiempo-limitado-f202510-n/ (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | MeriStation/AS | Spain | 17 October 2025 | Spain games/entertainment press: return to cinemas; dethroned Red Notice; Oscar push; $18M US sing-along weekend | R5 |

| (https://www.animationmagazine.net/2025/10/watch-kpop-demon-hunters-creator-maggie-kang-talks-sequels-spin-offs-more/ (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Animation Magazine (UTA talk) | US/Global | 14 October 2025 | Trade interview: UTA/Animation Magazine video-“Netflix’s biggest animated feature,” phenomenon framing | R6 |

| (https://ew.com/kpop-demon-hunters-creators-shut-down-live-action-movie-adaptation-11829534 (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Entertainment Weekly | US | 17 October 2025 | EW interview with voice cast on the film’s “enormous success” (reception framing) | R7 |

| (https://www.billboard.com/music/chart-beat/kpop-demon-hunters-soundtrack-number-one-billboard-200-1236066167/ (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Billboard | US | 14 September 2025 | Billboard 200: Soundtrack No. 1 (Chart Beat report) | R8 |

| (https://www.billboard.com/music/chart-beat/kpop-demon-hunters-returns-number-one-billboard-200-chart-1236082238/ (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Billboard | US | 5 October 2025 | Billboard 200: Soundtrack returns to No. 1 (follow-up report) | R9 |

| (https://www.billboard.com/music/chart-beat/kpop-demon-hunters-returns-number-one-billboard-200-chart-1236082238/ (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Billboard | US | 22 September 2025 | Hot 100: “Golden” No. 1 for 6 weeks (list/article) | R10 |

| (https://www.billboard.com/lists/huntr-x-golden-number-one-hot-100-eighth-week/ (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Billboard | US | 6 October 2025 | Hot 100: “Golden” No. 1 for 8 weeks (update) | R11 |

| (https://flixpatrol.com/title/kpop-demon-hunters-sing-along/top10/ (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | FlixPatrol (3rd-party analytics; descriptive) | Multi-country | 18 October 2025 | Regional Top-10 tracking (longevity across markets; complementary indicator) | R12 |

| (https://www.kedglobal.com/k-pop/newsView/ked202511050003 (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Korea Economic Daily Global (KED Global) | Korea/US | 16 October 2025 | Soundtrack multi-track Hot 100 presence (all 8 tracks charting; persistence) | R13 |

| (https://www.animationmagazine.net/2025/06/the-directors-of-kpop-demon-hunters-take-us-backstage-of-their-netflix-sony-showstopper/ (accessed on 26 November 2025)) | Animation Magazine | US/Global | 13 June 2025 | Background feature (pre-release/launch month) with directors on concept and women-led focus (contextual) | R14 |

Appendix B. Core Credits, EN Voices, and Key Songs

| Gender | Nationality | Name | Work/Character/Song | Role/Function | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman | Korean-Canadian | Maggie Kang | Film | Director; story; co-screenwriter | Authorship/Prod. |

| Man | American | Chris Appelhans | Film | Director; co-screenwriter | Authorship/Prod. |

| Woman | American | Hannah McMechan | Film | Co-screenwriter | Authorship/Prod. |

| Woman | Mexican-American | Danya Jimenez | Film | Co-screenwriter | Authorship/Prod. |

| Woman | American | Michelle L. M. Wong | Film | Producer (Sony Pictures Animation) | Authorship/Prod. |

| - | USA/Global | Sony Pictures Animation/Netflix | Film | Studio/Distributor | Authorship/Prod. |

| Woman | Korean-American | Arden Cho | Rumi | Speaking voice | EN Voice Cast |

| Woman | Korean-American | May Hong | Mira | Speaking voice | EN Voice Cast |

| Woman | Korean-American | Ji-young Yoo | Zoey | Speaking voice | EN Voice Cast |

| Man | Korean-Canadian/South Korean–based | Ahn Hyo-seop | Jinu | Speaking voice | EN Voice Cast |

| Man | South Korean | Lee Byung-hun | Gwi-ma | Speaking voice | EN Voice Cast |

| Woman | Korean-American | Yunjin Kim | Celine | Speaking voice | EN Voice Cast |

| Man | Korean-American | Daniel Dae Kim | - | Speaking voice (supporting) | EN Voice Cast |

| Man | Korean-American | Ken Jeong | - | Speaking voice (supporting) | EN Voice Cast |

| Man | Korean-American | Joel Kim Booster | - | Speaking voice (supporting) | EN Voice Cast |

| Woman | American | Liza Koshy | - | Speaking voice (supporting) | EN Voice Cast |

| Woman | Korean-American | EJAE | “How It’s Done” | Opening set | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | Audrey Nuna | “How It’s Done” | Opening set | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | REI AMI | “How It’s Done” | Opening set | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | EJAE | “Golden” | Narrative single | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | Audrey Nuna | “Golden” | Narrative single | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | REI AMI | “Golden” | Narrative single | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | EJAE | “Free” | Duet/mid-film | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | Korean-American | Andrew Choi | “Free” | Duet/mid-film | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | Korean-American | Andrew Choi | “Soda Pop” | Antagonist number | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | South Korean | Neckwav | “Soda Pop” | Antagonist number | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | Korean-American | Danny Chung | “Soda Pop” | Antagonist number | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | Korean-American | Kevin Woo | “Soda Pop” | Antagonist number | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | South Korean | samUIL Lee | “Soda Pop” | Antagonist number | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | Korean-American | Andrew Choi | “Your Idol” | Antagonist reveal | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | South Korean | Neckwav | “Your Idol” | Antagonist reveal | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | Korean-American | Danny Chung | “Your Idol” | Antagonist reveal | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | Korean-American | Kevin Woo | “Your Idol” | Antagonist reveal | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Man | South Korean | samUIL Lee | “Your Idol” | Antagonist reveal | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | EJAE | “What It Sounds Like” | Finale | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | Audrey Nuna | “What It Sounds Like” | Finale | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | REI AMI | “What It Sounds Like” | Finale | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | EJAE | “Takedown” | End credits (version) | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | Audrey Nuna | “Takedown” | End credits (version) | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | Korean-American | REI AMI | “Takedown” | End credits (version) | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | South Korean | Jeongyeon (TWICE) | “Takedown” | End credits (TWICE ver.) | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | South Korean | Jihyo (TWICE) | “Takedown” | End credits (TWICE ver.) | Songs (lead vocals) |

| Woman | South Korean | Chaeyoung (TWICE) | “Takedown” | End credits (TWICE ver.) | Songs (lead vocals) |

References

- Banet-Weiser, S. (2018). Empowered: Popular feminism and popular misogyny. Duke University Press. Available online: https://www.dukeupress.edu/empowered (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Berg, M. (2017). The importance of cultural proximity in the success of Turkish dramas in Qatar. International Journal of Communication, 11, 3415–3430. Available online: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6712 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Boman, B. (2022). Feminist themes in Hallyu 4.0 South Korean TV dramas as a reflection of a changing sociocultural landscape. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 28(4), 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, S. (Ed.). (2013). Pervasive animation. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lauretis, T. (1987). Technologies of gender: Essays on theory, film, and fiction. Indiana University Press. Available online: https://iupress.org/9780253204417/technologies-of-gender/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Entertainment Weekly. (2025, October 17). Arden Cho and May Hong on the healing impact of “K-Pop Demon Hunters” and their unexpected character connections. Entertainment Weekly. Available online: https://ew.com/kpop-demon-hunters-arden-cho-may-hong-healing-impact-character-connections-11831130 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Hyun, M.-Y., Jung, Y.-E., Kim, M.-D., Kwak, Y.-S., Hong, S.-C., Bahk, W.-M., Yoon, B.-H., & Kim, B.-S. (2014). Factors associated with body image distortion in Korean adolescents. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 10, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwabuchi, K. (2002). Recentering globalization: Popular culture and Japanese transnationalism. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- James, S. (2025). Affective Participation from the in-between: The Platformization of K-Pop fandom. Social Media + Society, 11, 20563051251351390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D. Y. (2016). New Korean wave: Transnational cultural power in the age of social media. University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. H. (2011). Virtual hallyu? Korean cinema of the global era. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., & Brunn-Bevel, R. J. (2023). No face, no race? Racial politics of voice actor casting in popular animated films. Sociological Forum, 38(4), 1111–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. (2005). Women, television and everyday life in Korea: Journeys of hope. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. (Ed.). (2013). The Korean wave: Korean media go global. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichanskaya, M. (2025, July 16). Interview with Maggie Kang, creator of “K-Pop Demon Hunters”. GeeksOUT. Available online: https://www.geeksout.org/2025/07/16/interview-with-maggie-kang-creator-of-kpop-demon-hunters/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Lauzen, M. M. (2025). The celluloid ceiling: Employment of behind-the-scenes women on top-grossing U.S. films in 2024. Center for the Study of Women in Television & Film, SDSU. Available online: https://womenintvfilm.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2024-Celluloid-Ceiling-Report.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Lee, H., Son, I., Yoon, J., & Kim, S.-S. (2017). Lookism hurts: Appearance discrimination and self-rated health in South Korea. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H. J., & Jin, D. Y. (2019). K-pop idols: Popular culture and the emergence of the Korean music industry. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Jeong, E. (2021). The 4B movement: Envisioning a feminist future with/in a non-reproductive future in Korea. Journal of Gender Studies, 30(5), 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesota, O., Parada-Cabaleiro, E., Brandl, S., Lex, E., Rekabsaz, N., & Schedl, M. (2022). Traces of globalization in online music consumption patterns: Domestic vs. foreign listening and recommender effects. In Proceedings of ISMIR 2022. Available online: https://archives.ismir.net/ismir2022/paper/000034.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Lie, J. (2015). K-pop: Popular music, cultural amnesia, and economic innovation in South Korea. University of California Press. Available online: https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520283121/k-pop (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Martínez León, P. (2020). La construcción de identidades de género en la ficción audiovisual y sus implicaciones educativas. Área Abierta, 20(3), 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R. (1970). Sisterhood is powerful: An anthology of writings from the women’s liberation movement. Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieborg, D. B., & Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4275–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofcom. (2025). Children and parents: Media use and attitudes report 2025. Ofcom. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C. (2023). K-pop dance music video choreography. In S.-Y. Kim (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to K-Pop (pp. 97–115). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y. (2018). Pop city: Korean popular culture and the selling of place. Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Y. (2023). Following in the footsteps of BTS: The global rise of K-pop tourism. In S.-Y. Kim (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to K-Pop (pp. 265–280). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R. (1995). Glocalization: Time–space and homogeneity–heterogeneity. In M. Featherstone, S. Lash, & R. Robertson (Eds.), Global modernities (pp. 25–44). SAGE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, A. N. (2025). Studying code switching in K-pop hits on Billboard charts (preprint). arXiv, arXiv:2509.23197. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. L., Choueiti, M., Pieper, K., & Clark, H. (2019). Increasing inclusion in animation: Investigating opportunities, challenges, and the classroom-to-the-C-suite pipeline. USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative & Women in Animation. Available online: https://assets.uscannenberg.org/docs/aii-inclusion-animation-201906.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Srnicek, N. (2016). Platform capitalism. Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Tronto, J. C. (2013). Caring democracy: Markets, equality, and justice. New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K. J. (2017). In the Time of Plastic Representation. Film Quarterly, 71(2), 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, P. (1998). Understanding animation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.-Y. (2022). Escaping the corset: Rage as a force of resistance and creation in the Korean feminist movement. Hypatia, 37(2), 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Captures | Values | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant shot scale of the scene. | WS/MS/CU/MIX | SHOT |

| Number of protagonists sharing the frame for most of the scene (0 = none; 1 = one; 2 = two; 3 = three). | 0–3 | TRIO_ONSCREEN_(0–3) |

| 1 = full-body competence (no sexualised fragmentation); 0 = otherwise. | 1/0 | BODY_FRAMING |

| Decision ownership/strategic competence visible (0 = absent; 1 = present/punctual; 2 = sustained/central). | 0–2 | AGENCY_(0–2) |

| Care/repair and collective alignment (0 = absent; 1 = present/punctual; 2 = sustained/central). | 0–2 | SORORITY_(0–2) |

| 1 = edits/moves that exalt synchrony; 0 = weak/absent. | 1/0 | CHOREO_CAMERA |

| 1 = marked palette/light transition tied to empowerment/jeopardy beats; 0 = none. | 1/0 | COLOUR_SHIFT |

| Korean cultural codes active in the scene (links to matrix in S1::Globalized_Codes). | Gx list | CULTURE_TAGS (G-codes) |

| Officially credited track associated with the scene. | track ID/title | Key song |

| Key Song | Label (Short) | Scene |

|---|---|---|

| How It’s Done | Opening performance | S1 |

| Golden | New epic single; first crisis | S2 |

| - | After Rumi’s crisis: reunion | S3 |

| Soda Pop | Antagonists’ public presentation | S4 |

| - | Bedroom confrontation & care | S5 |

| Free | Mid-film crisis & repair | S6 |

| Your Idol | Antagonists final number | S7 |

| What It Sounds Like | Climactic battle & acceptance | S8 |

| - | Community reprise/epilogue | S9 |

| KR Share % | EN Share % | Non- Lex | KR Words | EN Words | Hook ≤ 10 w | Song |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | 3 | 0 | 404 | “We could be free” | Free (duet) |

| 1.9 | 98.1 | 25 | 18 | 906 | “We’re going up… together we’re glowing” | Golden |

| 3.9 | 96.1 | 10 | 20 | 493 | “Huntrix don’t quit… how it’s done” | How It’s Done |

| 7.5 | 92.5 | 52 | 50 | 614 | “You’re my soda pop” | Soda Pop |

| 0 | 100 | 16 | 0 | 495 | “This is what it sounds like” | What It Sounds Like |

| 2.1 | 97.9 | 57 | 27 | 1286 | “I’m your idol” | Your Idol |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roca Vera, D. Local Voices, Global Circulation: Women’s Agency, Sorority and Glocalisation in K-Pop Demon Hunters. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040203

Roca Vera D. Local Voices, Global Circulation: Women’s Agency, Sorority and Glocalisation in K-Pop Demon Hunters. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(4):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040203

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoca Vera, Dácil. 2025. "Local Voices, Global Circulation: Women’s Agency, Sorority and Glocalisation in K-Pop Demon Hunters" Journalism and Media 6, no. 4: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040203

APA StyleRoca Vera, D. (2025). Local Voices, Global Circulation: Women’s Agency, Sorority and Glocalisation in K-Pop Demon Hunters. Journalism and Media, 6(4), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040203