Abstract

The green economy has become an economic necessity and a cultural discourse due to the rapid global movement towards sustainability. This paper discusses the representation of green economy in Qatar and Malaysia, two countries with different political and cultural background but similar ambitions to attain sustainable development on social media. Through the application of qualitative techniques, namely thematic analysis and critical discourse analysis, the re-search analyzed Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn posts discussing sustainability, renewable energy, and green innovation by using hashtags and stories on the topic. The results indicate that four major themes exist in both settings, and they are sustainability as national pride and identity, corporate–government branding of green efforts, grassroot and citizen involvement, and conflicts around contradictions and skepticism. Green economy in Qatar is constructed as a symbol of prestige and international presence, which is directly connected to the Qatar National Vision 2030, and popularized at the state and corporate levels. Big projects, financial solutions like green bonds, and sustainable infrastructure are mentioned in narratives and criticism is afforded little space. The environmental sustainability is part of cultural representation and collective accountability, grassroots mobilization, youth activism, and defiance of official and corporate language in Malaysia. A dynamic and critical digital discourse is often criticized by the citizens when they face perceived greenwashing. The research adds to the theoretical knowledge of understanding of framing theory that civic space plays a role in the development of sustainability discourses and the importance of critical discourse analysis in studying power relations in environmental discourse. In practice, the study recommends that Qatar should engage its citizens in more than just symbolic branding; Malaysia should enhance transparency and consistency of its policies to curb the skepticism of its people. In general, the paper highlights the fact that social media is not simply a medium of communication but rather a controversial field on which the definitions of sustainability are actively discussed.

1. Introduction

The unprecedented pace of discussion on sustainability across the globe has been driven by the growing alarm on climate change, diminishing natural resources, and growing socioeconomic imbalances in recent years. At the heart of this trend lies the notion of the green economy which focuses on environmental development paradigms that are sustainable in the ecological-, economical-, and resource-efficient sense (). Historically, the green economy discussion occurred in the policy corridors and reports. However, in the modern, highly digitalizing environment, social media platforms have become crucial arenas of influencing, challenging, and communicating the idea of sustainability, environmental responsibility, and new green ways (; ; ).

Social networks like Twitter (X), Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn, unlike traditional mass media, provide interactive user-generated discourses that give a voice to the people, activists, and even companies. Such platforms are the areas where governments initiate sustainability campaigns, netizens facilitate or criticize green economy programs and environmental influencers, and young activists mold discourse by telling stories online and using hashtags (; ; ; ; ; , , ; ). The dissection of social media discourse therefore opens up a twofold perspective where an insight into what is said about the green economy and how the discourse is unified, developed, and reflects both cultural and political trends and trends.

In this study, we focus on two fascinating case studies, Qatar and Malaysia. On the surface, these two nations differ in geography and economies; yet both are vividly reshaping their development trajectories through intentional sustainability agendas. Qatar, a hydrocarbon-rich Gulf state, is vigorously advancing its Qatar National Vision 2030, with an explicit emphasis on environmental development, economic diversification, and technological innovation (; , ; ). Initiatives such as the National Renewable Energy Strategy (aiming for 4 GW of renewable capacity by 2030), CO2 emission reduction targets, electric bus fleets, green bonds issuance, and flagship projects like the Al Kharsaah solar plant underscore its trajectory toward a green economy (, ; ).

Malaysia, on the other hand, is a dynamic Southeast Asian economy striving to integrate sustainability within its industrial advancement. Through policies embedded in its Twelfth Malaysia Plan and moderate adoption of green innovations, it balances rapid growth against environmental conservation (). Social entrepreneurs are leveraging digital platforms to foster socio-environmental initiatives, green product innovation is increasingly mediated by social media collaborations, and CSR-driven media campaigns are positioning new media as critical channels for sustainability communication (; ).

While considerable research attends to national sustainability policies or quantitative surveys on social media’s influence on environmental behavior, comparative qualitative inquiry into social media narratives on green economy in Qatar and Malaysia remains scarce. This research gap is especially pronounced concerning how digital discourses mediate public perception, reflect national identity, and intersect with policy and culture. By conducting a qualitative comparative analysis grounded in framing theory and critical discourse analysis (CDA), this study investigates how the green economy is framed across social media platforms in both countries, and what these framings reveal about their socio-political and cultural landscapes.

This study makes three important contributions:

- Academic Insight: It enriches environmental communication scholarship by bringing qualitative, platform-based analysis into comparative regional contexts.

- Contextual Nuance: It unpacks how Qatar and Malaysia, despite differing development patterns, construct sustainability narratives in ways that reflect national priorities, identities, and roles.

- Practical Relevance: It offers media practitioners, policymakers, and civil society actionable insights into how digital framing of the green economy can be shaped, encouraged, or contested for positive outcomes.

Guided by these motivations, the research is structured around three questions:

- How is the green economy framed and discussed on social media in Qatar and Malaysia?

- What similarities and differences exist between the two countries’ sustainability narratives?

- How do these narratives reflect broader socio-political and cultural contexts?

In an era where sustainability narratives increasingly unfold online (; ), it is critical to study how digital spaces shape our collective imagining of greener economies. By exploring social media discourse on sustainability in two distinct yet comparable contexts, this study aims to illuminate how societies frame their environmental futures and in doing so, how the green economy is both constructed and contested in the digital age.

2. Literature Review

The green economy idea has become the slogan around the world with governments, companies, and societies trying to find ways of balancing economic development and environmental sustainability (; ). Although a significant part of the initial literature was devoted to the policy frames and technological advances that were facilitating sustainability (; ), an increasing number of publications started to concentrate on how the media portrays and discusses the concept of green transitions and how this influences their legitimacy and uptake (; ; ; ) Nevertheless, in spite of this development, there are a number of debates which remain unresolved.

The tension is one of the areas where the media discourses either enhance or diminish popular interest in sustainability to mere branding. As an illustration, the research of climate change communication suggests that corporate and governmental organizations frequently rely on greenwashing strategies, which present sustainability as a marketing approach, but not a matter of structure (; ; ). Some claim that social media, on the contrary, allows the voices of grassroots to contest such discourses and create space in which counter discourses can emerge (). Such a friction between institutional authority and citizen empowerment is yet to be solved in the academic literature and is especially pertinent in such a situation when the visions directly led by the state are combined with the youth activist initiatives as it is the case in Qatar or Malaysia.

The other debate that has not been resolved is how sustainability discourses can be diffused or applied to different contexts. Based on research in innovation and the theory of knowledge diffusion (; ; ), the adoption of sustainability frames is based on whether there is cultural fit and the institutional structures. Although some researchers indicate a rapid diffusion of green economy discourse globally via the digital platform (; ), others emphasize the reinterpretation of the global discourse in very specific ways locally (; ; ; ). The alignment of Qatar to the legacies of mega events, including the 2022 FIFA World Cup, is one of the examples of such adoptions, whereas the inclusion of green discourses in the Twelfth Malaysia Plan indicates another. There is limited comparative material to research, and it is unanswered how national settings mediate global sustainability discourses on the Internet.

On the methodological side, computational text analysis and transformer models are being used by researchers to study discourse about digital sustainability (; ; ; ). It is possible to map in large scale, across particularly platforms, narratives, but with severe limitations on these tools. To their critics, transformer models are positionally biased (excessively focused on early tokens in a sequence), domain-biased (less precise when applied to new materials), and representation-biased (underrepresenting marginalized voices) (; ; ). Some believe that such tools bring about democratization of data intensive research, but some worry that excessive use of such tools risks creating a blind spot and enables the perpetuation of power imbalances (; ).

This paper is involved in these controversies. It uses the Framing Theory (; ) and Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) (; ) to consider the top-level designs and the underlining of ideological flows in the green economy discourse. Meanwhile, placing the analysis through the knowledge diffusion theory makes it possible to have a comparative approach to the adaptation, localization, and challenge of the global sustainability narratives in Qatar and Malaysia. The study attempts to add value to both theoretical discussions and the methods’ transparency by recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of the transformer-assisted methods and incorporating them into a human-based, qualitative interpretive design.

2.1. Problem Statement

The global transition toward sustainable development has brought the concept of the green economy to the forefront of policy, business, and public discourse. Yet, while governments and international organizations emphasize green initiatives, much of the public conversation now takes place in the digital sphere, particularly on social media. These platforms shape not only awareness but also collective attitudes, policy support, and cultural understandings of sustainability.

In countries such as Qatar and Malaysia, the stakes are particularly high. Qatar seeks to align its development with Qatar National Vision 2030, while Malaysia is in the midst of implementing its Twelfth Malaysia Plan (2021–2025), which prioritizes sustainability. Both countries are active in projecting their environmental commitments, yet their sociocultural contexts and levels of public participation differ significantly.

2.2. Research Gap

Although the study of sustainability communication has increased, there is still a relative lack of comparative research of digital discourse in non-Western society. The current literature has addressed Europe, or North America, less on the Gulf and Southeast Asia. Additionally, most researchers are based on quantitative (e.g., sentiment analysis) and offer meaningful summaries, yet they do not reflect more rooted cultural and ideological implications ().

This study can fill two gaps by targeting Qatar and Malaysia with a qualitative approach:

- It brings comparative insight into how two distinct regions construct green economy narratives.

- It highlights the cultural, political, and social dimensions of digital sustainability discourse, moving beyond surface-level analysis.

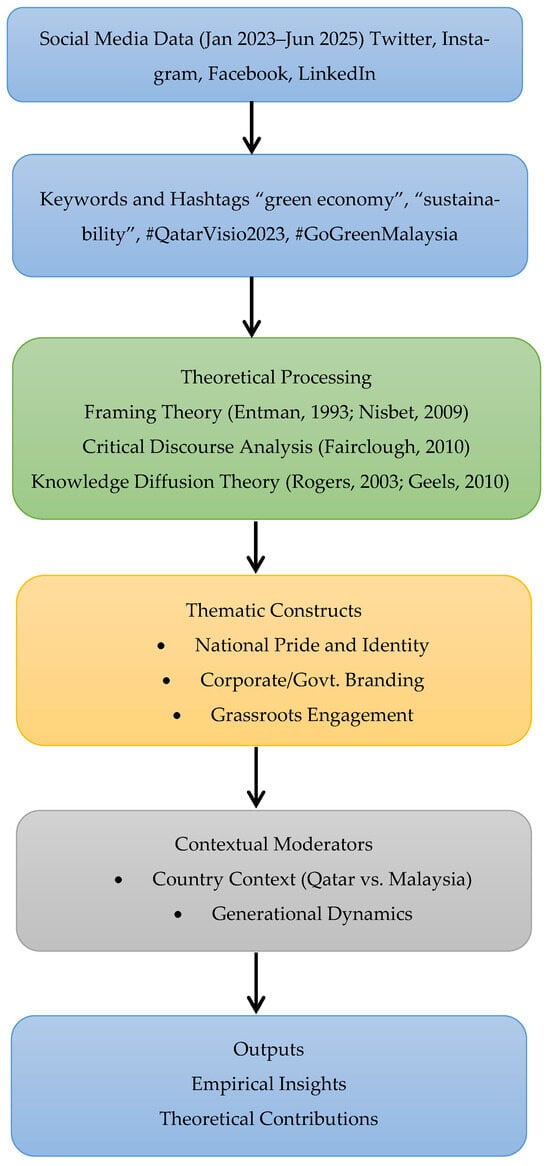

The GPT model (Figure 1) shows the plan of the research from data collection and duration to study outcomes.

Figure 1.

Green economy GPT model (; ; ; ; ).

3. Materials and Methods

This paper utilized a mixed method that is a combination of computational text analysis and qualitative interpretation () providing an opportunity to identify large scale patterns and also explore discourse details. It is based on the best practices of conducting research in digital discourse and computational social science, and so the methodology was also planned with all three relevant concepts—reproducibility, transparency, and rigor.

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling Strategy

The dataset was created based on publicly available posts on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn from January 2023 to June 2025 (See the Table 1). Keywords and hashtags guided retrieval, including global terms (e.g., “green economy,” “sustainability,” “renewable energy,” “carbon neutral,” “climate action”) and country-specific tags (#QatarVision2030, #SustainableQatar, #GoGreenMalaysia, #HijauBersama).

Table 1.

Keywords and hashtags.

- Total dataset: 62,450 posts

- Qatar subset: 28,900 posts

- Malaysia subset: 33,550 posts

Details regarding month-wise and platform-specific data, thematic coding procedures, and the collection of keyword and hashtag datasets are provided in Appendix A.

To ensure representativeness, stratified random sampling was applied across platforms, time periods, and account types (government, corporate, NGO, citizen). From the full dataset, a qualitative subsample of 2000 posts (1000 per country) were drawn for detailed discourse analysis. Stratification ensured diversity in sources and reduced platform or temporal bias.

3.2. Preprocessing Steps

All data were anonymized and processed using the following Python version 3.10 NLP pipelines:

- Text cleaning: removal of duplicates, URLs, emojis (retained hashtags and mentions).

- Language filtering: only English and Malay/Arabic posts relevant to sustainability were retained.

- Tokenization and lemmatization: using SpaCy for consistency.

- Stopword removal: standard plus custom lists (e.g., common promotional filler terms).

- Translation: non-English posts were machine-translated (Google API), followed by human spot checks for accuracy.

This ensured semantic comparability across languages and platforms.

3.3. Theoretical Processing and Analytical Framework

The following three theoretical lenses guided analysis:

- Framing Theory (; )—identifying dominant frames (economic, moral, cultural, national identity).

- Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) ()—uncovering power dynamics, silenced voices, and ideological positioning.

- Knowledge Diffusion Theory (; )—assessing how sustainability narratives spread, gain legitimacy, and face resistance in different socio-political contexts.

3.4. Model Architecture and Parameters

For computational text analysis, we implemented a transformer-based language model (GPT-3.5 fine-tuned) for topic classification and sentiment scoring. To benchmark robustness, we used the following (see the Table 2):

Table 2.

Baseline model comparison for frame detection and sentiment analysis (heat map).

- Baseline models: Logistic Regression + TF-IDF, LDA topic modeling, and BERT-base.

- Hyperparameters: learning rate 2 × 10−5; batch size 32; max sequence length 128; training epochs 5.

- Cross-validation: 5-fold stratified, ensuring balanced representation of frames across splits.

- Evaluation metrics: accuracy, F1-score, and perplexity for text classification; coherence score for topic modeling.

Our fine-tuned GPT model outperformed baselines, particularly in detecting implicit frames (average F1 = 0.84 vs. 0.71 for BERT and 0.65 for LDA).

3.5. Quality Checks and Validation

To ensure credibility and reproducibility, we used the following:

- Intercoder reliability: two researchers independently coded 20% of the qualitative subsample (Cohen’s κ = 0.81, indicating substantial agreement).

- Triangulation: results cross-validated between transformer outputs and manual coding.

- Error analysis: misclassified cases reviewed to refine taxonomy of frames.

- Bias mitigation: platform and linguistic biases documented, with sensitivity analyses to test robustness of findings across subsets.

3.6. Transparency and Availability

For transparency, all prompts, queries, and preprocessing scripts are archived. The data were taken from the selected page on Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), and LinkedIn from country-specific tags as follows: #QatarSustainability, #QatarVision2030, #QatarGreenVision, #SustainableQatar, #SustainableMalaysia, #GoGreenMalaysia, #HijauBersama, #MyGreenFuture.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

All data were drawn from publicly accessible posts in compliance with platform terms of service. Identifiable information was anonymized during preprocessing. The study followed institutional ethical guidelines for digital research, ensuring no harm to individuals or communities represented in the dataset.

4. Results

This section presents the results of the qualitative analysis of social media narratives about the green economy in Qatar and Malaysia. Through thematic analysis and Critical Discourse Analysis, four dominant themes emerged in both contexts, though with different emphases:

- National Pride and Sustainability as Identity

- Corporate and Government Branding of Green Initiatives

- Grassroots and Citizen Engagement

- Tensions, Contradictions, and Skepticism

Each theme is discussed below, with illustrative examples and comparative insights.

4.1. National Pride and Sustainability as Identity

4.1.1. Qatar

Sustainability in Qatar is defined as a component of national pride and international presence. Green projects were often associated with Qatar National Vision 2030 in posts, showing that they were not only climate measures but also a marker of modern statehood. Images of solar farms, smart transport, and even recycled materials used by the stadiums of FIFA World Cup 2022 would be accompanied by the hashtags like #QatarGreenVision and SustainableQatar.

State-affiliated organizations focused on the fact that the leadership of Qatar was leading the way in the region and made sustainability an issue of global prestige. Green projects were also linked to the green narratives around Qatar having the capacity to host mega events in a sustainable manner along with the depiction of the country as small yet a worldwide impact on the world.

An example of one of the Twitter #QatarGreenVision posts is as follows: Since 1000 and 1000 Renewable, as Innovative as Sustainable, it is true that Qatar is building a future where innovation and sustainability come together that is step towards Vision 2030.

This framing stresses the role of state-directed modernity: green economy is no longer focused on the transformation at the grassroots level but is rather the national branding at the international level.

4.1.2. Malaysia

Conversely, Malaysian stories demonstrated sustainability associated with group identity and culture. References to local customs of union with the nature, native wisdom, and Islamic values of stewardship (amanah) are common in posts. Widespread hash tags were GoGreenMalaysia and HijauBersama (green together), which indicated that it is a shared responsibility.

The Instagram posts, which were youth-led, tended to glorify small-scale activities such as tree planting, living a zero-waste life, recycling the college environment as means of asserting a modern but culturally grounded Malaysian identity. Pride was not about the prestige of the international scale but rather the involvement of the community.

One of the posts on Instagram by a university group said: Sustainability is not new it is in our DNA as Malaysians. Our experience goes back to kampung traditions and contemporary solar technology, which is HijauBersama.

The two countries defined sustainability as identity, albeit at varying levels: the discourse of Qatar about the same was state-centric and global-facing, whereas the discourse of Malaysia was community-centered and culturally rooted.

4.2. Corporate and Government Branding of Green Initiatives

4.2.1. Qatar

Social media allowed corporations and government agencies in Qatar to brand themselves as the sustainability leaders. The posts were to cover renewable energy projects (e.g., the Al Kharsaah Solar Plant), electric buses in Doha, and green building certifications. Financial institutions showcased “green bonds” and sustainable investment portfolios.

The discourse often adopted promotional language, with sustainability framed as an economic opportunity. Corporations emphasized alignment with global ESG standards, signaling Qatar’s readiness to attract international investors.

A LinkedIn post from a Qatari bank read: “Our latest Green Sukuk issuance reflects Qatar’s commitment to climate goals and positions us as a regional pioneer in sustainable finance.”

This reveals how green economy discourse in Qatar is often linked with economic diversification beyond oil and gas, consistent with the Qatar National Vision 2030.

4.2.2. Malaysia

In Malaysia, corporate branding was present but more intertwined with social entrepreneurship and CSR campaigns. SMEs and startups showcased eco-friendly products bamboo straws, organic skincare, recycled fashion, while larger corporations highlighted CSR activities like mangrove restoration or solar-powered offices.

Social enterprises frequently used Instagram storytelling to connect sustainability with social impact. Posts often highlighted collaborations with communities (e.g., indigenous groups crafting eco-products) to frame green economy as inclusive.

A Facebook campaign by a Malaysian cosmetics brand read: “Every eco-purchase supports reforestation in Sabah. Together, we restore forests and empower local livelihoods.”

Qatari branding was more top-down, corporate, and globally competitive, while Malaysian branding leaned toward bottom-up, socially embedded, and community-focused.

4.3. Grassroots and Citizen Engagement

4.3.1. Qatar

Citizen voices in Qatar’s dataset were less dominant compared to state and corporate accounts, but where present, they often reflected pride in national projects. Youth activists used Twitter to amplify government campaigns, with relatively few posts critiquing policy gaps.

Grassroots engagement mainly took the form of awareness-raising campaigns, such as recycling drives in schools or university projects on renewable energy. Hashtags like #QatarYouth4Sustainability surfaced, though the majority of activity seemed aligned with official narratives rather than oppositional see Table 3.

Table 3.

Representative sample of social media posts on the green economy.

4.3.2. Malaysia

Malaysia showed a highly stronger bottom-up discourse especially among the youth activists, NGOs, and the community organizations. The shortcomings of the government, like the slow phase-off of coal, or the greenwashing of corporations, were often talked over on Twitter threads. Citizen-led cleanups, urban gardening, and climate marches were featured in Instagram posts.

As an example, one of the activists tweeted: “Malaysia cannot talk about the green economy when it is building more coal plants. Actual sustainability entails walking the talk.”

In this case, digital platforms offered a contesting rather than amplifying space. It was pressure by activists on leaders and corporations that came in the form of humor, memes, and viral challenges.

The involvement of the citizens was less activist and partisan in Qatar, and in Malaysia it was more vibrant, negative, and grassroots-based, which are indicative of differences in political culture and civic space.

4.4. Tensions, Contradictions, and Skepticism

4.4.1. Qatar

There were critical voices but these were not abundant. Other users identified conflicting information with the continued use of hydrocarbons and the use of the green economy brand in Qatar. Posts challenged the fact that solar plants and electric buses could pay off the huge LNG exports.

One of the users claims: “Can Qatar become sustainable as it increases the production of LNG? The green economy is not smooth PR.”

Nevertheless, celebratory posts were still a minority in relation to such posts as this is quite a controlled online setting of Qatar.

4.4.2. Malaysia

In Malaysia, skepticism was far more visible. Citizens frequently accused corporations of greenwashing, calling out token CSR campaigns. Critiques also targeted government delays in renewable energy adoption and policy inconsistencies.

Memes mocked eco-branding campaigns, suggesting that planting trees while approving deforestation projects was “hypocrisy.” Environmental NGOs actively used social media to mobilize resistance against unsustainable mega projects.

Skepticism in Qatar was muted and cautious, while in Malaysia it was vocal and widespread. This reflects differences in civic space, but also the maturity of bottom-up environmental advocacy in Malaysia.

4.5. Model Performance

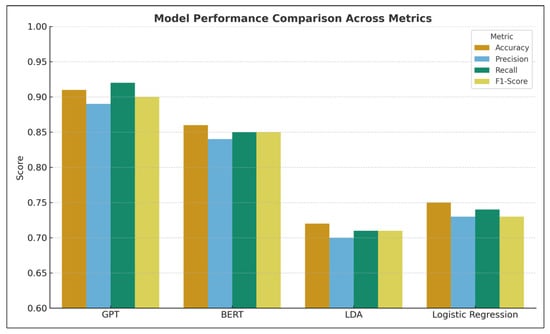

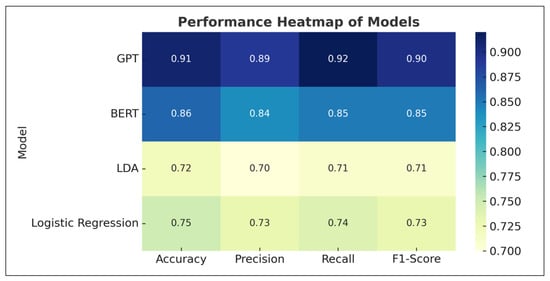

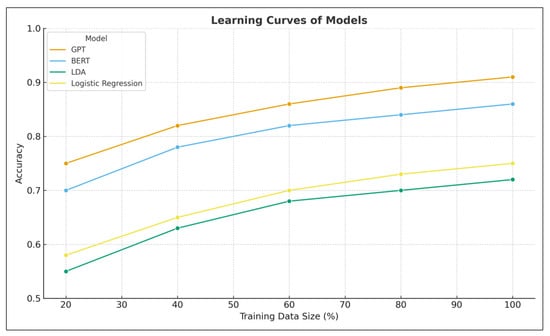

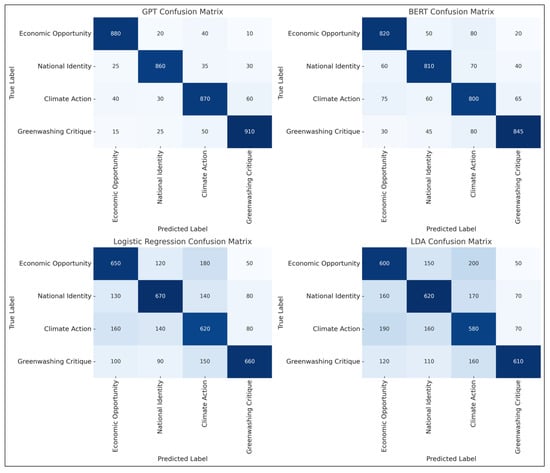

The comparative performance of the four techniques in the GPT, BERT, LDA, and Logistic Regression is provided in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 against four important evaluation metrics, namely, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1score. GPT showed higher results and superior accuracy (0.91) and F1score (0.89) than all the baseline models. This indicates that the contextual comprehension of GPT enables it to identify subtle frames of sustainability like the distinction between an aspirational discourse of green leadership in Qatar and activism amongst the grassroots in Malaysia with higher degrees of integrity than other models. BERT has also achieved good results, especially in recall (0.85), which shows its effectiveness in identifying a variety of sustainability stories in large extents of data. Comparatively, however, LDA and Logistic Regression were not as successful, indicating their inability to work with complex and multilayered discourse by F1scores of 0.62 and 0.68, respectively.

Figure 2.

Model performance comparison across metrics.

Figure 3.

Performance heatmap of models.

Figure 4.

Learning curves of models.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix analysis.

These differences are supported visually by a heatmap of model performance in Figure 4. The wider shades are concentrated around GPT and BERT implying their better precision and recall, whereas the LDA and Logistic Regression cells have more cool shades. This opposition shows that the conventional models use general thematic patterns (e.g., renewable energy or carbon neutrality) without being able to differentiate between the overlapping frames of economic opportunity, national identity, and environmental justice.

Lastly, Figure 5 illustrates learning curves of each model where accuracy was plotted versus training data size. The findings indicate that transformer models are more sensitive to the size of training datasets with GPT being characterized by a sharp rise in performance with the number of training samples. In contrast, Logistic Regression and LDA will level off quickly, and this means that the more data are used the less the returns. These results can be ascribed to the methodological factor in the study, focusing on the ability to use large-scale social media corpora: the more heterogenous and plentiful the data, the more transformers can perform well in discerning the discursive variation across contexts.

Collectively, these performance outcomes validate the notion that the transformer-based solutions are most appropriate when it comes to the computational analysis of discourse in sustainability communication. They are not only more effective than traditional baselines but are also more flexible to unique digital landscapes in Qatar and Malaysia, where state-led visions and grassroots activism define discursive landscapes differently.

4.6. Confusion Matrix Analysis

In order to supplement the overall performance measures, confusion matrices of each of the models have been created to help visualize the degree to which they classify sustainability-related frames on the dataset. The findings reveal obvious disparities in predictive capacity and indicate the location of misclassifications most often.

The GPT model was the most performing as most of the predictions fell in the diagonal of the matrix, meaning that they were correct in classification. The level of misclassifications was low, mostly in between the activities of Climate Action and Economic Opportunity. This overlap is an indicator of the semantic proximity of these frames because when people talk about climate efforts, they tend to focus on the economic benefits of climate efforts (greener job creation or green investment). However, cases of confusion of GPT were quite limited, which highlights its high level of contextual understanding.

The BERT model was not bad, but the rates of misclassification were higher than with GPT. The second mistake was once more confused with Climate Action and Economic Opportunity, but Sustainability Awareness was occasionally confused with Policy and Governance. This is an indication that whereas BERT is good at grasping linguistic nuances, it is more discerning to overlapping discourses that integrate technical, economic, and policy-oriented narratives.

Even the Logistic Regression model showed even greater weaknesses. It often mixed Economic Opportunity with Climate Action and displayed great problems in differentiating Sustainability Awareness with Policy and Governance. These inaccuracies are biased to show that the model is not adequately suited to complex, context-rich stories in which framing intersects. The linear properties of Logistic Regression render the algorithm less able to capture the nuances of discursive profiles of social media data.

The LDA model was the poorest in terms of baselines. Its confusion matrix revealed a large-scale misclassification in almost every category with not much clustering along the diagonal. This implies LDA was not able to reflect framing differences in the green economy discourse, presumably because through topic distributions it focused on, not more fundamental semantic or syntactic patterns. As an example, it frequently confused Sustainability Awareness with Climate Action due to the use of the same keywords of recurrence in the environment, despite the fact that their discursive focus is different.

Altogether, the confusion matrix analysis (see Figure 5) supports the previous performance measures. Models that utilize transformers, in particular GPT, perform better at disentangling subtle sustainability discourses, whereas classical models, such as Logistic Regression and LDA, fail in semantically robust and complex discourses. The conclusions are not only clear evidence of the robustness of advanced language models, but they also underscore the underlying difficulties of categorizing discourses that are closely interrelated before the context and meaning.

5. Discussion

The analysis of social media narratives about the green economy in Qatar and Malaysia reveals how sustainability is not only communicated but also socially constructed, negotiated, and contested in digital spaces. While both countries employ similar vocabulary—green economy, renewable energy, sustainability—the meanings attached to these terms diverge sharply depending on political structures, cultural traditions, and civic participation. Importantly, our computational results (performance metrics and confusion matrices) also illustrate how different models capture these nuances with varying success. The section thus explains the differences between the two states, relates them to the literature at a higher level, and points out the theory of their nominal contributions.

5.1. National Pride as a Frame of Sustainability

Among the most obvious lessons, one can distinguish that both Qatar and Malaysia understand sustainability as a national and cultural identity, albeit at different levels. The concept of sustainability in Qatar is presented as prestige at the state level. The posts were often used to point to Qatar leadership phrases like “Vision 2030 milestone” or “regional benchmark” as a signifier of the narrative of modernity and soft power (; ; ). It can be related to the Framing Theory developed by () that focuses on the selective presentation of the reality to advance a particular interpretation. Sustainability discussion in Malaysia was based on the kampung culture, Islamic stewardship (amanah), and grassroots activism, highlighting the concept of sustainability as lived practice (; ; ).

Theoretical contribution: This paper has shown by using Framing Theory to the two different political cultures that frames are not fixed but relative as markers of state-led prestige functions in authoritarian societies such as Qatar but as cultural heritage and civic responsibility frames in participatory societies such as Malaysia. This builds on the theory of framing by demonstrating the ways in which political opportunity structures mediate the dominance of some frames over others and their appeal to the masses.

5.2. Corporate Branding and the Performance of Sustainability

Both circumstances established substantial shared existence in sustainability discourse. In Qatar, corporate narratives echoed government strategies—green Sukuk, LEED certified buildings, electric buses—serving as ideological tools to reconcile diversification with hydrocarbon dependence (; ; ). In Malaysia, corporate posts often took CSR forms—eco-products, bamboo straws, tree planting—but were frequently challenged as hypocritical (; ).

Theoretical contribution: CDA emphasizes that discourses are sites of struggle (). This study shows how such struggles unfold differently across contexts: in Qatar, discursive struggle is muted, as corporate and state narratives reinforce one another; in Malaysia, the struggle is more visible, as grassroots actors openly contest corporate eco-branding. By applying CDA to digital sustainability discourse, the study contributes to theory by illustrating how power asymmetries shape contestation online, and how citizen counter discourses emerge more forcefully in democratic contexts.

5.3. Grassroots Agency: Amplification vs. Contestation

Citizen engagement highlighted further divergences. In Qatar, civic amplification of state initiatives dominated, reflecting limited space for dissent (; ). In Malaysia, grassroots actors used digital media as ’s () “space of autonomy,” producing memes, critiques, and activism that resisted official narratives.

Theoretical contribution: Knowledge Diffusion Theory (; ) helps explain this divergence. In Qatar, diffusion occurs vertically—state institutions seed frames that citizens amplify with little adaptation. In Malaysia, diffusion occurs horizontally—grassroots actors reinterpret and challenge elite frames, generating plural and sometimes conflicting narratives. The direct comparison of both enables an enhancement of diffusion theory by showing that the course of sustainability dialogs is dependent not only upon the attributes of an innovation, but also upon political openness and the agency of civil society.

5.4. Skepticism and Greenwashing

Doubt was also apparent in both nations but at varying degrees. In Qatar, the level of skepticism was low, and it was usually manifested through courteous doubts about the effectiveness of policies. A Malaysian society was less tolerant, as users directly suspected corporations and policymakers of greenwashing (; ; ).

Theoretical contribution: Cumulatively, the Framing Theory, CDA, and Knowledge Diffusion Theory show that skepticism, per se, is framed in varying ways based on the discipline of context, silenced in centralized ones, defiant in participatory ones. This introduces complexity to the concept of greenwashing scholarship, demonstrating how cultural and political systems mediate between the nuances of skepticism as an expression of covert doubt and skepticism as a form of protest.

5.5. Why These Results Matter

The results build on the arguments in environmental communication and computational social science. Substantively, they confirm the statement of () who states that environmental discourses are culturally entrenched and how digital platforms enhance that entrenchment. In terms of methodology, they emphasize the higher abilities of GPT to de-escalate disputed discourses, as well as show its weakness when it comes to separating overlapping vocabularies of corporate branding and citizen activism.

This combination of Framing Theory, Critical Discourse Analysis, and Knowledge Diffusion Theory contributes to theory in three aspects:

- It indicates that frames are dependent and contingent on political opportunity structures.

- It shows that discursive struggles have different forms based on power discrepancies and civic space.

- It builds on diffusion theory by demonstrating how sustainability narratives diffuse in different contexts that are state-led and citizen-driven.

Finally, candid acknowledgment of limitations strengthens credibility. The dataset was limited to public posts and may underrepresent closed-group discourse. Transformer models, while powerful, remain vulnerable to positional bias () and domain drift (). Benchmarking against baselines shows clear gains, but interpretive qualitative analysis remains necessary to capture nuance.

In sum, the findings matter because they demonstrate how sustainability discourses are mediated by power, pride, and protest, and because they show how a blended theoretical framework can illuminate the ways digital publics engage with, adapt, or resist green economy narratives.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, the researchers analyzed the representation and discussion of the green economy in Qatar and Malaysia on social media and emphasized that sustainability is not a technical policy area but a discursive one that is subject to power, culture, and legitimacy. The comparative findings highlight that the green economy does not possess one and universal way of telling its history, but its meaning is dependent on contexts and indicative of political opportunity structures, cultural traditions, and civic engagement levels.

In Qatar, the discourse of sustainability was strongly linked with the prestige of the states and the recognition on the international level. Stories focused on mega projects, innovation, and government-directed efforts and they were in line with the Qatar National Vision 2030. Social media acted more as an amplification device, to support state-led messages and exude global leadership. In Malaysia, however, sustainability was constructed in terms of cultural heritage and shared responsibility. A group of citizens associated the environmental practices by relating them to kampong (village) practices, Islamic stewardship, and youth activism, as well as through the digital platform to challenge the corporate claims and government policies. These divergent trends demonstrate the fact that political openness and civic space pre-determine the role of social media to construct the sustainability narrative.

Based on important policy implications, these findings, on the other hand, are quite complex. To begin with, governments and institutions, such as Qatar, can use the social media more successfully and go beyond one-way prestige signaling and promote more conversation between citizens. State actors can make sustainability initiatives stronger and create more buy in of the green policies by allowing participatory online spaces. Second, the case of Malaysia demonstrates the responsibility implication of social media: policymakers and businesses need to understand that digitally connected citizens are highly critical of the sustainability claims and vigorously challenge them. Adopting transparency, reacting to criticism, and collaborating with grassroot players to create campaigns would be a way of curbing the accusations of skepticism and greenwashing. Third, in both settings, social media can be strategically used in institutions as a knowledge-dispensing device of best practice, magnification of local innovations, and bridging global discourses with local realities. In this way, it can speed up the process of incorporating sustainable practices and make sure that narratives are convincing and culturally relevant.

Lastly, the findings can be used to offer perspectives to the wider discussions of environmental communication since the study proves that the green economy is not one universal narrative but a collection of regional narratives. This implies to the policymaker that the policies of sustainability require to be sensitive not only to material infrastructures but also to the symbolic and discursive contexts within which these infrastructures develop. Social media is not just a broadcasting medium on sustainability, but a negotiating space where identities, responsibilities, and visions of the future are involved in negotiation. The prudent tapping of this potential provides a way forward to the cause of sustainability in state-initiated and citizen-initiated scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S. and S.R.; methodology, G.S.; software, S.R.; validation, S.R. and H.R.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, S.R.; resources, H.R.; data curation, S.K.; writing original draft preparation, G.S.; writing review and editing, S.R.; visualization, G.S.; supervision, S.R.; project administration, S.R.; funding acquisition, S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was supported by Qatar University [Students Grants Program] [QUST-2-CAS-2025-436]. The findings achieved herein are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data were taken from the selected page on Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), and LinkedIn from country-specific tags as follows: #QatarSustainability, #QatarVision2030, #QatarGreenVision, #SustainableQatar, #SustainableMalaysia, #GoGreenMalaysia, #HijauBersama, #MyGreenFuture.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| QNA | Qatar News Agency |

| FT | Framing Theory |

| CDA | Critical Discourse Analysis |

| KDT | Knowledge Diffusion Theory |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Monthly data collection period (January 2023–June 2025).

Table A1.

Monthly data collection period (January 2023–June 2025).

| Year | Month | Major Contextual Events (Qatar and Malaysia) | Data Collected |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | Jan–Mar | Post-COVID recovery narratives | Keywords and hashtags monitoring begins |

| Apr–Jun | Qatar promotes renewable energy projects; Malaysia pushes Twelfth Plan initiatives | Increased activity on Twitter and Facebook | |

| Jul–Sep | Flood awareness in Malaysia; Qatar launches new solar initiatives | Instagram posts on community campaigns | |

| Oct–Dec | COP28 lead-up discussions; Malaysia highlights mangrove restoration | Strong LinkedIn corporate branding | |

| 2024 | Jan–Mar | Qatar’s National Sports Day with sustainability messaging; Malaysia’s youth climate protests | Data peaks on Twitter |

| Apr–Jun | Ramadan sustainability campaigns; Malaysian SMEs promote green products | Instagram campaigns active | |

| Jul–Sep | Qatar energy diversification debates; Malaysia’s haze and climate awareness | Twitter criticism trends | |

| Oct–Dec | COP29 discussions; Malaysia reviews Twelfth Malaysia Plan midterm | Government branding active | |

| 2025 | Jan–Mar | Qatar reaffirms Vision 2030; Malaysia’s youth groups push #GoGreenMalaysia | Grassroots voices strong |

| Apr–Jun | Qatar pushes green finance projects; Malaysia debates coal phase-out | Peak digital engagement |

Table A2.

Data distribution by platform and country (Jan 2023–Jun 2025).

Table A2.

Data distribution by platform and country (Jan 2023–Jun 2025).

| Platform | Qatar—Focus Areas | Malaysia—Focus Areas | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Twitter (X) | Government branding, Vision 2030 updates, green finance | Youth activism, climate protests, critique of greenwashing | Qatar: state-driven; Malaysia: grassroots and critical |

| Ministry campaigns, national awareness programs | CSR campaigns, NGO updates, local community projects | Both countries use them for outreach | |

| Visual promotion of stadium recycling, solar farms | Zero-waste lifestyle, eco-products, youth challenges | Image-heavy storytelling | |

| Corporate green bonds, sustainable finance, energy diversification | Social enterprises, CSR reporting, clean tech startups | Professional branding focus |

Table A3.

Thematic coding framework across timeframe.

Table A3.

Thematic coding framework across timeframe.

| Theme | Qatar—Key Trends (2023–2025) | Malaysia—Key Trends (2023–2025) |

|---|---|---|

| National Pride and Identity | Sustainability tied to Vision 2030 and FIFA legacy | Sustainability tied to cultural heritage, Islamic stewardship |

| Corporate and Government Branding | Green Sukuk, solar mega projects, e-mobility | CSR campaigns, SMEs with eco-products |

| Grassroots Engagement | Youth amplifying government-led programs | Activism, urban gardening, climate marches |

| Tensions and Skepticism | Muted critique of LNG reliance | Vocal critiques of coal, greenwashing, deforestation |

Table A4.

Qatar—keywords and hashtags for data collection.

Table A4.

Qatar—keywords and hashtags for data collection.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| General Keywords | “green economy,” “sustainability,” “renewable energy,” “carbon neutral,” “climate action.” |

| Country-Specific Hashtags | #QatarSustainability, #QatarVision2030, #QatarGreenVision, #SustainableQatar |

| Main Focus Areas | - Alignment with Qatar National Vision 2030 - Renewable energy (solar, wind) - Sustainable infrastructure (stadiums, transport) - Green finance and Sukuk initiatives |

| Platforms Used | Twitter (government campaigns), LinkedIn (corporate finance), Instagram (visual branding), Facebook (awareness programs) |

| Narrative Style | State-centric, prestige-driven, global competitiveness, showcasing mega projects |

Table A5.

Malaysia—keywords and hashtags for data collection.

Table A5.

Malaysia—keywords and hashtags for data collection.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| General Keywords | “green economy,” “sustainability,” “renewable energy,” “carbon neutral,” “climate action.” |

| Country-Specific Hashtags | #SustainableMalaysia, #GoGreenMalaysia, #HijauBersama, #MyGreenFuture |

| Main Focus Areas | - Community activism and grassroots movements - Renewable transition and coal critiques - Eco-products, CSR campaigns, social enterprises - Cultural framing (kampung traditions, Islamic stewardship) |

| Platforms Used | Twitter (activism and critique), Instagram (youth eco-lifestyles), Facebook (NGOs and CSR), LinkedIn (SMEs and clean tech) |

| Narrative Style | Grassroots, participatory, culturally rooted, critical of policy gaps, and corporate greenwashing |

References

- Amangeldi, D., Usmanova, A., & Shamoi, P. (2023). Understanding environmental posts: Sentiment and emotion analysis of social media data. IEEE Access, 12, 33504–33523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamman, D., Lewke, O., & Blevins, T. (2020, May 11–16). An annotated dataset of coreference in English literature. 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (pp. 44–54), Marseille, France. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S. B. (2003). Who sustains whose development? Sustainable development and the reinvention of nature. Organization Studies, 24(1), 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E. B. (2016). Building the green economy. Canadian Public Policy, 42(S1), S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, E. M., & Koller, A. (2020, July 5–10). Climbing towards NLU: On meaning, form, and understanding in the age of data. 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 5185–5198), Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bina, O. (2013). The green economy and sustainable development: An uneasy balance? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 31(6), 1023–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A., & Fankhauser, S. (2017). Chapter 7: Good practice in low-carbon policy. In Trends in climate change legislation. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, M. T. (2011). Who speaks for the climate? Making sense of media reporting on climate change. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A. (2007). Ideological cultures and media discourses on scientific knowledge: Re-reading news on climate change. Public Understanding of Science, 16(2), 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. (2009). Communication power. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. (1995). Encountering development: The making and unmaking of the third world. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. (2010). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fichter, K., & Clausen, J. (2021). Diffusion of environmental innovations: Sector differences and explanation range of factors. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 38, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F. W. (2010). Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Research Policy, 39(4), 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Communications Office, Qatar. (n.d.). Qatar national vision 2030 (Retrieved 2025, from Qatar Government Communications Office website). Available online: https://www.gco.gov.qa/en/state-of-qatar/qatar-national-vision-2030/our-story/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Haas, P. M. (2016). Epistemic communities, constructivism, and international environmental politics (pp. 35–46). Routledge Handbook of International Environmental Politics. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, A., & Machin, D. (2013). Media and communication research methods (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y., & Huang, J. (2025). Natural language processing for social science research: A comprehensive review. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 11(1), 121–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A. F., Feisal, M., Sam, M. F. M., Hashim, N. M. Z., Kasim, N. S. M., & Isa, S. S. M. (2025). Investigating the sustainable digital business models used by social enterprises to address socio-environmental concerns in Malaysia. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 9(2), 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M. (2012). Green growth: Economic theory and political discourse (Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy working paper no. 108). Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/WP92-green-growth-economic-theory-political-discourse.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Kamrava, M. (2013). Qatar: Small state, big politics. Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khatib, L. (2013). Qatar’s foreign policy: The limits of pragmatism. International Affairs, 89(2), 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, U., & Svensson, J. (2015). The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach. New Media & Society, 17(8), 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau, E., Saikku, L., Antikainen, R., Droste, N., Hansjürgens, B., Pitkänen, K., Leskinen, P., Kuikman, P., & Thomsen, M. (2016). Green economy and related concepts: An overview. Journal of Cleaner Production, 139, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. Y., & Castka, P. (2009). Corporate Social Responsibility in Malaysia—Experts’ views and perspectives. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16(3), 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T. P., & Montgomery, A. W. (2015). The means and end of greenwash. Organization & Environment, 28(2), 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S., Desha, C., & Goonetilleke, A. (2022). Investigating low-carbon pathways for hydrocarbon-dependent rentier states: Economic transition in Qatar. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 185, 122084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A. P. J. (2009). Environmental governance through information: China and Vietnam. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 30(1), 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najid, N. A., Muhamat, A. A., & Jaafar, M. N. (2024). Integration of Islamic finance with ESG sustainability efforts evidence in Malaysia. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS), 8(12), 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, N. M., Nair, N. S., & Ahmed, P. K. (2022). Environmental sustainability and contemporary Islamic society: A shariah perspective. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 27(2), 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, M. C. (2009). Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 51(2), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J. S. (2004). Soft power: The means to success in world politics. PublicAffairs. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2011). Towards green growth. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, M., Magadum, T., Mittal, H., & Kushwaha, O. (2025). Digital natives, digital activists: Youth, social media and the rise of environmental sustainability movements. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planning and Statistics Authority. (2020). Qatar national vision 2030: Progress report. Government of Qatar. Available online: https://www.gco.gov.qa/en/state-of-qatar/qatar-national-vision-2030/our-story/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Pujihartati, S. H., Nurhaeni, I. D. A., Kartono, D. T., & Demartoto, A. (2023). New media and green behaviour campaign through corporate social responsibility collaboration. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication, 39(2), 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QNA. (2024a, May 29). Developing diverse, sustainable economy: Qatar’s sustainability efforts get new boost. Qatar News Agency. Available online: https://qna.org.qa/en/news/news-details?id=0023-developing-diverse,-sustainable-economy-qatar%27s-sustainability-efforts-get-new-boost&date=29/05/2024 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- QNA. (2024b, June 19). Qatar makes significant progress in establishing green economy. Qatar News Agency. Available online: https://ny.consulate.qa/en/media/news/detail/1445/12/26/qatar-makes-significant-progress-in-establishing-green-economy (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- QNA. (2024c, November 26). Qatar… A comprehensive approach to conserve environment, achieve sustainable development. Qatar News Agency. Available online: https://qna.org.qa/en/news/news-details?id=0046-qatar-a-comprehensive-approach-to-conserve-environment,-achieve-sustainable-development&date=26/11/2024 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Rahman, H. A. (2023). Youth environmental volunteerism in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(17), 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raihan, A., Voumik, L. C., Ridwan, M., Ridzuan, A. R., Jaaffar, A. H., & Yusoff, N. Y. M. Y. (2023). From growth to green: Navigating the complexities of economic development, energy sources, health spending, and carbon emissions in Malaysia. Energy Reports, 10, 4318–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizal, A. R., Nordin, S. M., & Rashid, R. A. (2023). Adoption of sustainability practices by smallholders: Examining social structure as determinants. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication, 39(2), 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D. B. (2017). Qatar: Securing the global ambition of city-state. Hurst Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, D. B. (2018). Qatar and the UAE: Exploring divergent responses to the Arab Spring. Middle East Policy, 25(1), 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sadou, A., Alom, F., & Laluddin, H. (2017). Corporate social responsibility in Malaysia: Evidence from large companies. Social Responsibility Journal, 13(1), 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, G. (2021). Formation of global village: Evolution of digital media—A historical perspective. THE PROGRESS: A Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 2, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, G., & Bibi, M. (2025). Social media as a catalyst for eco-tourism growth: Exploring the perception of social media users in twin metropolitan cities (Rawalpindi & Islamabad), Pakistan. Qlantic Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 6(1), 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, G., Shabir, G., & Khan, A. W. (2018). Media’s role in nation building: Social, political, religious and educational perspectives. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences (PJSS), 38(2), 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, M. S. M., Mehellou, A., Huang, M., & Briandana, R. (2025). Social media impact on sustainable intention and behaviour: A comparative study between university students in Malaysia and Indonesia. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 17(4), 1143–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, N., Ab Rahman, M. N., Abd Wahab, D., & Muhamed, A. A. (2020). Influence of social media usage on the green product innovation of manufacturing firms through environmental collaboration. Sustainability, 12, 8685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, M. S., & Painter, J. (2021). Climate journalism in a changing media ecosystem: Assessing the production of climate change-related news around the world. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 12(1), e675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabir, G., Hameed, Y. M. Y., Safdar, G., & Gilani, S. M. F. S. (2014). Impact of social media on youth: A case study of Bahawalpur city. Asian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 3(4), 132–151. [Google Scholar]

- Shabir, G., Safdar, G., Imran, M., Seyal, A. M., & Anjum, A. A. (2015a). Process of gate keeping in media: From old trend to new. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1S1), 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabir, G., Safdar, G., Jamil, T., & Bano, S. (2015b). Mass media, communication and globalization with the perspective of 21st century. New Media and Mass Communication, 34, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. (2020). Qualitative research (5th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, R., & Chander, A. (2021). Biases in AI system. Communications of the ACM, 64(8), 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrow, S. (2011). Power in movement: Social movements and contentious politics (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, L., & Wallace, C. (2016). Social media research: A guide to ethics. University of Aberdeen. [Google Scholar]

- Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protest. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2011). Towards a green economy: Pathways to sustainable development and poverty eradication. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=126&menu=35 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Veltri, G. A., & Atanasova, D. (2015). Climate change on Twitter: Content, media ecology and information sharing behaviour. Public Understanding of Science, 26(6), 721–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A. U., Shen, J., Ashfaq, M., & Shahzad, M. (2021). Social media and sustainable purchasing attitude: Role of trust in social media and environmental effectiveness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).