3.2. Media Education of the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv and Lviv Polytechnic National University

In March 2018, a three-day training was organized in Kyiv at the initiative of the Ukrainian Press Academy and with the support of DW Akademie, the main goal of which was to train specialists in the field of media literacy. One of the authors of the publication, Nataliia Voitovych, participated in this training event and received a media literacy trainer certificate, gaining valuable practical experience and professional competencies necessary for the further dissemination of media education practices. As the result of this professional growth the author created the course “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” and it was implemented into the educational process of the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv. Initially included in the curriculum of the Faculty of Journalism, the course was later offered as an elective for students from other faculties of the university. Over the course of six academic years, the course was taken by 697 full-time students representing over 17 majors, both humanities and natural sciences. Traditionally, the largest number of students remain from the Faculty of Journalism, but students from the Faculties of Foreign Languages, International Relations, and Law also showed significant interest. Among natural science majors, the most active in studying media literacy was demonstrated by students of the faculties of biology, geography, economics, as well as electronics and applied mathematics. The course “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” is taught as an elective subject in the first semester for 3rd year students. Every year, the number of students is constantly growing: the figures range from 62 to 157 people.

As a logical continuation of this course, in the second semester, as a discipline of free choice, students were offered another author’s course—“Critical Thinking and Media”. The dynamics of the number of students who chose this course ranged from 50 to 185 people. Over the course of five years, 698 students took it.

As a result, both courses—“Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” and “Critical Thinking and Media”—were mastered by 1395 full-time students of the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv. They effectively used this opportunity to improve their own competencies in the field of media literacy and the development of critical thinking.

It is worth noting that both courses are certified by the international organization IREX, which implements them with the support of the US Embassy and the British Embassy in Ukraine, in partnership with the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine and the Academy of the Ukrainian Press within the project “Learn and Distinguish: Infomedia Literacy.”

As part of the media literacy course, students mastered a number of relevant topics, including: journalistic standards, fake news, disinformation, gender stereotypes, hate speech, cybersecurity, cyberbullying, manipulative techniques, expert selection, hidden advertising, clickbait, sexism, post-truth, information bubble, influence of media owners, as well as distinguishing between facts and judgments.

The course notes state that by studying the academic discipline “Critical Thinking and Media”, students will become familiar with the basic principles of critical thinking, as well as consider the role of mental processes in the creation and consumption of information. Studying the course will help students understand the concepts of “information aggression”, “propaganda”, “manipulation”, “fake news”, “stereotypes” and learn to resist them, as well as fact-check the information received. During lectures and practical classes, students will learn the main methods of psychological influence on recipients, the psychological characteristics of the target audience, overcome stereotypes, and learn to think outside the box.

The aim of teaching the discipline is to familiarize students with the key concepts of critical thinking. Students must acquire and master the skills of critical thinking, analysis, fact-checking, and resistance to manipulative technologies used in the media.

Learning outcomes: Students should know the basic principles of fact-checking, the psychological characteristics of target audiences, the main methods of psychological influence on the recipient, and stereotypes and prejudices that are relayed through the media. Students must learn the skills of critical thinking, analysis, processing and use of information, in particular, recognizing fake and true information, avoiding and confronting manipulative technologies, and being aware of the risks of propaganda and disinformation.

And studying the course “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” will help students understand the concepts of “information aggression”, “propaganda”, “manipulation”, “fake news”, “stereotypes” and learn how to resist them, as well as fact-check the information received. During lectures and practical classes, students will learn the main methods of psychological influence on recipients, the psychological characteristics of the target audience, overcome stereotypes, and learn to think outside the box. During the study period, in addition to theoretical study of lecture material, students completed practical tasks and thematic exercises, which contributed to the consolidation of theoretical material in practice. For each lesson, appropriate tasks were selected taking into account the topic and didactic goal. Practical materials were borrowed from educational and methodological resources: Integration of infomedia literacy into the educational process. Educational and methodological materials of the project “Learn to Discern: Media Literacy” (

Integration of media and information literacy into the educational process (

2019). Educational and methodological materials of the project “Learn to Discern: Media Literacy”, 2019), “Practical media literacy guidebook for multipliers” (

Ivanov, 2019), “Media literacy: technologies and practical application” (

Voitovych & Imbirovska-Syvakivska, 2024), Media and information literacy online: A trainer’s manual, (

Taranenko, 2021).

The article “Media Literacy for Students of the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv: Implementation Challenges” presents the main practical tasks that students perform in practical classes and a detailed structure of the course “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” (

Voitovych, 2022, pp. 28–36).

In 2018, a survey was conducted among students and trainees of the Junior Academy of Sciences to determine the level of awareness of the concept of “media literacy”, interest in various aspects of this topic, and ideas about ways to spread media literacy among young people. 96.9% of respondents were mostly students, the remaining 3.1% were schoolchildren who were also students of the Junior Academy of Sciences. As a result of the survey, 96 questionnaires with answers were received.

Among the main questions were three: Is this the first time you have encountered the concept of “media literacy”? 17.7% of respondents answered that, unfortunately, it was the first time, 71.9% wrote that they were already familiar with this concept, and only 10.4% stressed that they were well-versed in the topic.

The second question was as follows: “Which block, in your opinion, is the most necessary to study and disseminate among the public to increase information literacy?” The question provided several options for answers. Thus, 58.3% of respondents answered that it was the block “Manipulation, propaganda, distortion of information”, the second place—55.2% of respondents chose the block “The role of critical thinking in the process of perceiving media messages”, the third place—41, 7% of young people chose the block “Online tools for verifying information”, the fourth place—29.2% of students chose the block “Interactive forms and methods in the process of teaching media literacy”, the fifth place—according to the results of the survey—was taken by the block “Information security”.

In response to the question “Other”, some respondents suggested training and fact-checking. The third question was: “Which of the listed options for implementing media education in your opinion has the greatest impact on its development and dissemination in Ukraine?”. The question was also multivariate. According to 57.4% of respondents, the most influential on the development of media education will be “the introduction of “Media Literacy” in the educational process as a separate subject”, 45.7% of students believed that it is necessary to “conduct similar training for a wide range of participants”, and one-third of respondents—31.9%—that it is necessary to “integrate “Media Literacy” into most subjects of the educational process” (

Ivanov et al., 2023). Most respondents consider the introduction of a separate subject on media literacy into the educational process effective, which confirms the need for a systematic and targeted approach to the formation of critical thinking. At the same time, a significant portion of students support the idea of conducting trainings for a wider audience, which demonstrates the demand for informal education in this area. The appeal of a third of respondents to an integration approach, which involves the inclusion of elements of media literacy in most academic subjects, demonstrates the desire for interdisciplinarity and the need for comprehensive development of media competencies.

The Faculty of Journalism of the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv listened to students’ requests. In the 2025–2026 academic year, the discipline “Media Literacy and Critical Thinking” is offered to 3rd-year students, and elements of media literacy are integrated into a number of academic disciplines—“Media Economics”, “History of Ukrainian Journalism”, “Organization of the Press Service”, “Ethical and Legal Norms of Journalism”, “Political Image in the Structure of the Communication Space”, which are certified by the international organization IREX, which implements them with the support of the US Embassy and the British Embassy in Ukraine, in partnership with the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine and the Academy of the Ukrainian Press within the project “Learn and Distinguish: Infomedia Literacy”, as well as “Media Security” and “Theory and Methodology of Journalism: Informational and Analytical Genres.”

The results of a study conducted by the Academy of Ukrainian Press in 2023 show that educators are interested in spreading media literacy. In their opinion, “media education should cover as many areas as possible, including fully educational (not individual academic subjects). Respondents see the need to introduce mandatory study of a media literacy course as an invariant component of typical educational programs. Then it is possible to achieve better results and efficiency in the dissemination of media literacy knowledge.” (

Research results on the implementation of media education practices in secondary schools, 2023).

At Lviv Polytechnic National University, master’s students are offered a course titled “Information Security and Information Warfare in the Media”, while second-year undergraduate students take “Media Security”. These courses provide students with fundamental knowledge about disinformation, fake news, and manipulative content. They are taught to recognize, detect, and resist disinformation on the Internet.

Each year, more than 130 journalism students complete these courses. Additionally, during Global Media and Information Literacy Week, lecturers conduct open interactive media literacy sessions for journalism students of various academic years.

A comparative perspective on media education and media literacy reveals both their shared goals and distinct functions in combating disinformation in Ukraine and abroad. Media education is understood as a formal, often institutionalized process that equips students and citizens with theoretical knowledge about media systems, communication models, and the socio-political role of information flows (

Buckingham, 2003). Media literacy, by contrast, emphasizes practical competencies such as critical evaluation of sources, fact-checking, and resistance to manipulative narratives (

Hobbs, 2010). In Ukraine, the urgency of wartime disinformation has accelerated initiatives that integrate media education into curricula and foster media literacy campaigns targeting the broader population, often with the support of civil society and international partners (

Dovbysh & Ocheretyana, 2022). In countries such as Finland or Estonia, media literacy is deeply embedded in school programs and public life, contributing to societal resilience against foreign propaganda (

Carlsson, 2019;

Salomaa & Palsa, 2021). Meanwhile, in the United States and Western Europe, media literacy is frequently linked to digital literacy, focusing on algorithmic awareness and social media use (

Mihailidis, 2018). This comparison suggests that while media education provides the theoretical foundation, media literacy operationalizes these insights into everyday practices, and their combined application is particularly critical for Ukraine’s information security in the face of hybrid warfare.

3.3. Results of the Survey of Journalism Students’ Ability to Recognize Disinformation

In order to determine whether journalism students are able to recognize and identify disinformation, a descriptive survey was conducted. A total of 277 journalism students from different academic years (ranging from 1 to 5.5 years of study) participated in the survey.

Almost all respondents (93.9%) reported that they know what media literacy is and are familiar with its basic principles and foundations. 4.7% of respondents reported that they are not sufficiently familiar with the basics of media literacy, while the remaining 1.4% stated that they do not know the basics of media literacy at all. A significant majority (95.3%) indicated that they are able to detect fake news and disinformation in the media, which suggests that journalism students possess essential skills for identifying disinformation messages. However, 2.9% admitted that they do not notice disinformation content online. One respondent explained that they do not encounter disinformation because they prefer to consume only reliable and high-quality media. The rest of the respondents noted that they very rarely come across suspicious content. Furthermore, the majority of respondents (88.4%) stated that they verify suspicious information or content that appears to contain fake elements. Only 7.2% reported that they do not verify such information, while the remaining participants indicated that their actions depend on specific circumstances. Nearly all surveyed journalism students (98.9%) believe that the spread of disinformation poses a threat to Ukraine’s information space. One respondent answered that they do not consider disinformation dangerous, while the rest remained undecided.

The main platforms for spreading such disinformation are predominantly social media platforms (97.1%) and online media (62.1%). Respondents also reported encountering disinformation messages on television (23.1%) and radio (5.1%). According to the participants, print mass media contained the least amount of disinformation. This question allowed respondents to choose multiple options, so many selected several platforms where they most often noticed disinformation.

Most frequently, disinformation and fake content are distributed through hyperlinks, as indicated by the majority of respondents (59.2%). Disinformation was also spread using images (29.9%) and video materials (9.4%). The rest answered that they didn’t notice disinformation.

Telegram was identified as the leading platform for the spread of fakes and disinformation—242 respondents selected it. (This question also allowed multiple responses.) The second most mentioned platform was TikTok (201 respondents), followed by Facebook in third place (135 respondents), and Instagram in fourth (105 respondents). Viber and X (formerly Twitter) shared fifth and sixth places, as these platforms were reported to have the least amount of fake information.

The results of the study show that journalism students are able to detect and recognize disinformation on social platforms and in the media. While combating this type of content is quite difficult, the respondents believe that the most effective method is through educational and explanatory video materials disseminated on social platforms—a view shared by 61% of respondents. Additionally, 18.1% believe that more explanatory information should be provided in the mass media, while 17.3% recommend organizing more disinformation-related training sessions for various age groups, professions, and social segments of the population. Other respondents chose the option «Your version», where they pointed out that it is necessary to introduce discipline with the basis of media literacy into educational institutions (schools, colleges, universities).

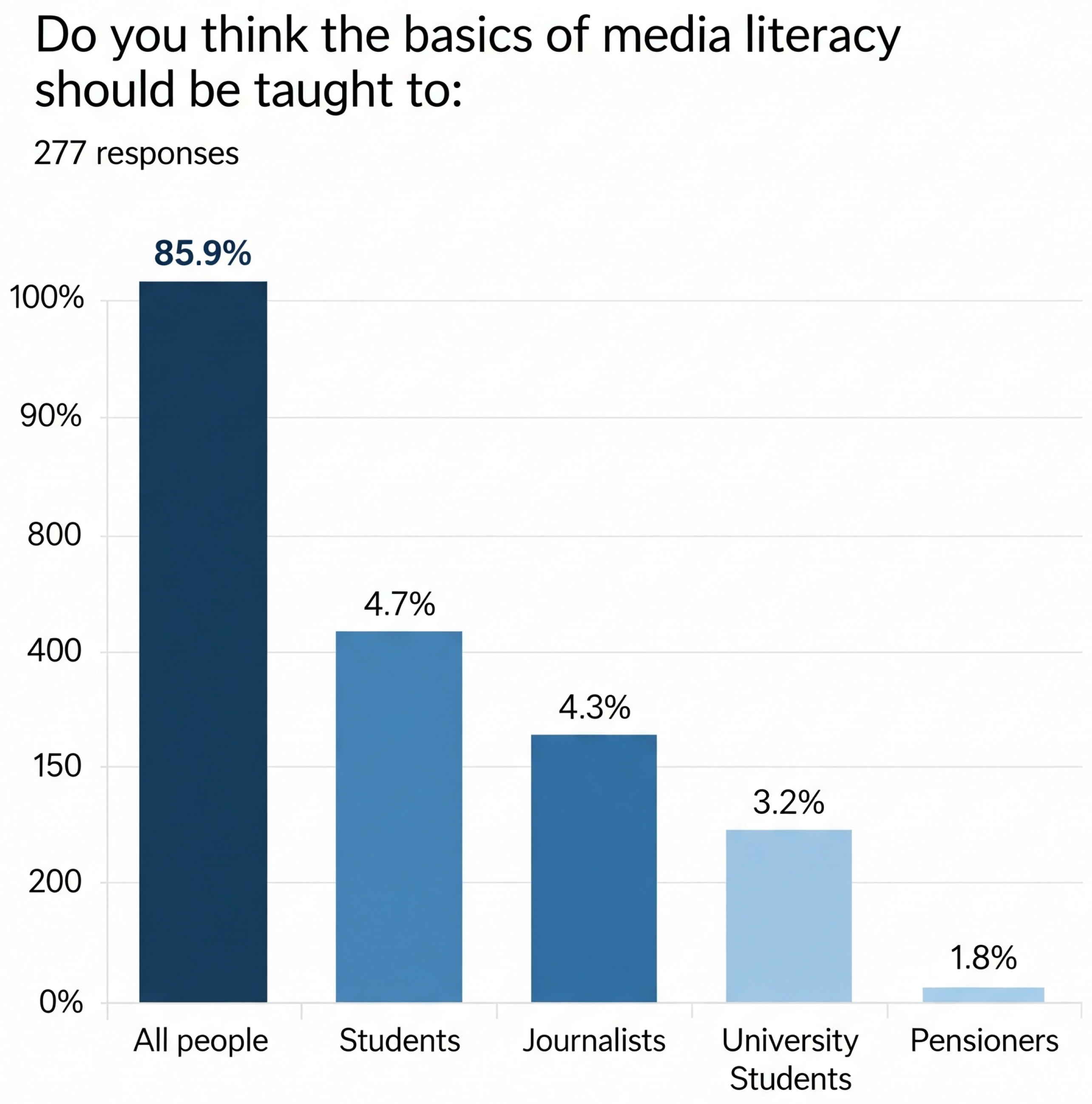

Other respondents stated that it is essential to teach the basics of media literacy in schools and to cultivate critical thinking among the public. They also suggested that strict criminal liability should be introduced for creating and spreading disinformation. A total of 238 respondents agreed that everyone should be taught the fundamentals of media literacy (

Figure 1).

Thus, journalism students from the two Lviv universities possess basic knowledge of media literacy, are able to distinguish fake news and manipulations, and view disinformation as a threat to the country’s information space. They believe that media literacy should be taught not only to journalism students but to all people, both in Ukraine and globally.

This perspective highlights students’ willingness to apply their knowledge in practice. Consequently, the universities offer specialized courses that allow for a deeper understanding of media literacy and its practical applications.

As an elective discipline, third-year students at Ivan Franko National University of Lviv choose the course “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application.” The dynamics of enrollment indicate a steady growth of interest in this educational offering. Specifically, in the 2020/2021 academic year, 62 students took the course; in 2021/2022—132 students; in 2022/2023—108 students; in 2023/2024—157 students; and in 2024/2025—152 students of the university.

In addition to this course, taught in the first semester, students in the second semester have the opportunity to take the discipline “Critical Thinking and Media.” For example, in the 2023/2024 academic year, 185 students of Ivan Franko National University of Lviv enrolled in this course.

The course “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” is offered in the first semester and consists of 8 lectures and 8 practical classes. In the second semester, students study the course “Critical Thinking and Media,” which also includes 8 lectures and 8 practical classes. Both lecture and practical sessions, conducted by Associate Professor Nataliia Voitovych, are based on the use of interactive teaching methods. For instance, during the class on “Fact and Opinion,” students are divided into pairs and groups to complete exercises that help them distinguish between the two concepts. Each student must formulate an opinion, and their partner reformulates it into a factual statement, and vice versa. This exercise develops critical thinking skills and attentiveness to different levels of information.

Among other methods is the exercise “Snowflake,” which demonstrates that each individual perceives information differently, forming their own interpretation. While studying topics related to discrimination and hate speech, students analyze a historical case—the conflict in Rwanda between the Tutsi and Hutu tribes. Particular attention is paid to the rhetoric broadcast by “Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines,” which illustrates how media messages can provoke social conflict and violence.

Another exercise used in practical classes is “Identify Hate Speech in Headlines.” Students receive a selection of media texts and must identify examples of discriminatory or toxic formulations, then propose alternative headlines free from hate speech. Such interactive practices not only facilitate the assimilation of theoretical material but also help students develop practical skills of analysis, interpretation, and the creation of ethical media content.

Studying the courses “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” and “Critical Thinking and Media” is extremely important for students, as they foster essential skills of analyzing and interpreting information required in today’s media environment. Practical tasks aimed at distinguishing facts from opinions, identifying hate speech, or analyzing propaganda texts help future professionals learn to critically evaluate content and work responsibly with information. This contributes not only to the professional growth of journalism students but also to the formation of active civic engagement, as media literacy and critical thinking are key competencies of contemporary society.

To enhance the effectiveness of the educational process within the course

“Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” (

Voitovych & Imbirovska-Syvakivska, 2024), a textbook titled

“Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” was developed in 2024. The textbook was authored by Associate Professor Natalia Voitovych from the Department of Theory and Practice of Journalism at Ivan Franko National University of Lviv (lecturer of the courses

“Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” and

“Critical Thinking and Media”) and Assistant Liliya Imbirovska-Syvakivska.

The textbook aims to familiarize students and a wider audience with the fundamental concepts and challenges of media literacy, stimulate interest in the topic, and foster the development of critical thinking skills.

In May 2024, the textbook was presented in an online event (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIYBg0_uATo accessed on 15 April 2025), which was open to all interested participants, including students. The presentation received numerous positive responses. For example, third-year student Antonina from Ivan Franko National University of Lviv commented:

“Thank you for an engaging and useful broadcast! I believe this information is extremely important for contemporary society.” Student Anastasiya D. noted:

“Thank you for providing interesting and relevant information.” Listener Mia remarked:

“Thank you for this textbook and your work. The broadcast was very informative.” Viktoriya S. highlighted:

“Thank you! It was valuable and will remain so.” Student Olena shared:

“I have saved the textbook. Media literacy is a crucial skill, especially at present.” Diana V. emphasized:

“The textbook structure is very interesting, and I particularly appreciated the glossary.” Finally, listener Daria summarized:

“Thank you for the broadcast. Your effort was evident, and it was very useful.”The textbook is structured around 14 topics, fully aligned with the curriculum of the course “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application.” It covers a wide array of subjects, from foundational principles of media literacy and journalistic standards to the analysis of media owners’ influence on content, political and commercial “paid content” phenomena, the role of sociology in electoral processes, toxic headlines, and fact-checking as a key tool to counter propaganda and disinformation.

Several chapters focus on issues such as stereotypes, discrimination, xenophobia, and hate speech. Considerable attention is also given to the impact of digital technologies, including bullying and cyberbullying, as well as cybersecurity challenges. The concluding chapters explore evidence-based medicine in combating misinformation and the intersection of media literacy with environmental issues.

A key feature of the textbook is its glossary, which provides concise and precise definitions of essential media literacy terms. Each topic includes self-assessment questions and practical exercises, suitable for both seminar activities and independent student work.

It is important to trace how these approaches are implemented in the practice of higher education. That is why the analysis of the curricula of academic disciplines taught at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv and the Lviv Polytechnic National University makes it possible to identify different levels of student training and the specifics of the formation of competencies in the field of media literacy, critical thinking, and information security.

The Lviv Polytechnic National University offers a course called “Information Security and Information Warfare in the Mass Media” for students of the master’s level of education. Its goal is to develop in-depth knowledge of the nature of information warfare and skills to counter information aggression in future journalists. The program pays significant attention to the analysis of specific cases, in particular, Russia’s information campaigns against Ukraine, US psychological operations in Haiti, as well as the spread of fake news during the COVID-19 vaccination period. The discipline is focused on training specialists for analytical and managerial activities in the field of national security.

As for the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, it offers undergraduate students the courses “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” and “Critical Thinking and Media.” They are elective subjects and are aimed at developing basic skills in critical perception of information.

The course “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Applications” is aimed at familiarizing students with key concepts of media literacy, fact-checking tools, and methods of countering disinformation. Topics covered within the discipline include “Clickbait as Media Bait,” “Stereotypes and Hate Speech,” “Manipulation in Politics,” and “Fake News and Fact-Checking.” Practical classes are built on interactive methods, including exercises such as “Fact and Statement”, “Cat in the Bag of Information”, “Political Games”, analysis of talk shows and media headlines. A special feature is the integration of international educational resources, including the Very Verified online course and materials from the IREX project “Learn and Distinguish”.

The course “Critical Thinking and Media” combines an interdisciplinary approach and provides students with knowledge of the psychology of information perception, social and media manipulation, as well as topics related to societal challenges. The curriculum includes the topics “Bullying and Cyberbullying in Modern Society”, “Gender Issues in the Media”, “Evidence-Based Medicine Against Fakes”, “Climate Change and Environmental Problems through the Lens of the Media”. Practical tasks focus on analyzing medical and environmental fakes, detecting manipulation of digital data, and working with interdisciplinary cases.

Thus, the course “Media Literacy: Technologies and Practical Application” and the course “Critical Thinking and Media” at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv are focused on developing basic skills to distinguish facts and statements, identify propaganda, avoid stereotypes, and counteract manipulation in the media. At the same time, the course “Information Security and Information Warfare in the Media” at the National University “Lviv Polytechnic” is in-depth and prepares students for professional activity in the conditions of information warfare, focusing on issues of state information policy, strategies for countering propaganda and protecting national interests.