1. Introduction

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in the writing and production of journalistic texts has been a subject of debate in the scientific community, with intense production in recent years, including, among other issues, numerous ethical concerns, in a context in which its frequent use in the journalistic profession is becoming a palpable reality.

From the analysis and processing of data prior to writing to the automation of content, assistance in writing, the personification of content, verification, transcription, and translation, among other uses, these different applications raise numerous ethical dilemmas that have been widely discussed by the scientific community, such as transparency, originality and authorship, the veracity of the content generated, and the risk of technological dependence.

Examining the impact of AI on journalistic writing, particularly the ethical implications of its use, offers a valuable framework for understanding the transformations that the profession is currently undergoing. This perspective not only anticipates shifts in editorial routines and content production, but also highlights the emerging competencies that journalists must develop to operate effectively in AI-integrated newsrooms.

The academic debate has increasingly emphasised the ethical dilemmas posed by AI in journalism, especially in relation to transparency and authorship. A deeper exploration of these issues will contribute to the formulation of self-regulatory mechanisms that can guide responsible use and reinforce public trust in the media. By addressing these challenges, the profession can move toward a more ethically grounded and transparent integration of AI technologies.

In fact, the absence of such codes has led many media outlets and journalists to develop their own internal protocols for the responsible use of AI. The study of all these tools can help to identify areas of interest to be shared and gaps to be filled so standardised patterns can be established.

The aim of this paper is to analyse the positioning of Spanish journalists regarding the use of AI and in what sense they regulate the declaration of its use for the generation of written and audiovisual content, including the use of algorithms to generate content. Thus, the following research question is posed:

The paper starts from a contextual framework that addresses the advancement of AI in the journalistic profession and the ethical dilemmas that arise around issues such as transparency and authorship. Within this framework, some emerging regulatory frameworks and ethical and normative recommendations are analysed, as well as some outstanding self-regulatory proposals and examples of good practice.

3. Materials and Methods

With the aim of investigating the positioning of journalists and media outlets regarding the impact of AI on newsrooms and transparency, this research uses a mixed methodology, combining quantitative methods based on surveys to determine the position of journalists and editors on the use of AI and ethical challenges, and qualitative methods, with in-depth interviews, to better understand how journalists approach the idea of transparency in the use of AI, exploring perceptions from a qualitative perspective based on experience and professional practice.

The choice of this methodology seeks to harness the potential of both methods: quantitative, to statistically measure positioning and frequency of use, and qualitative, to explore in depth certain perceptions, challenges, and opportunities for journalists and audiences.

The survey seek to investigate the use of different AI tools, especially regarding content production; the instructions and guidelines received, where applicable, on the use of these tools; self-regulation; desirable regulatory systems; and journalists’ perceptions of transparency. These questions provide the statistical data necessary for the initial analysis of the first phase of the investigation.

In designing the questionnaire, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) was applied, as it offers a valuable framework to understand how journalists perceive and engage with AI-driven tools. According to the TAM, the likelihood of adopting a new technology depends primarily on its perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, meaning that AI systems are more likely to be embraced when journalists believe that these tools improve reporting efficiency, improve content quality, or facilitate investigative processes, while being also intuitive and accessible. This study incorporated the TAM approach by including items that measure aspects such as perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEOU), attitude towards use, and behavioural intention to use.

The target population for this study consists of journalists working in newsrooms, which is a fairly limited universe. For this investigation, a sample of 50 individuals performing editorial tasks was randomly selected from newsrooms in different Spanish provinces, with a varied profile in terms of media, including print, digital, and audio-visual destinations.

The quantitative instrument used was a questionnaire. The form was distributed through email, social media, and distribution lists of journalist groups, ensuring anonymous and voluntary access for participants. The data collected through the online questionnaire, designed and distributed using Google Forms, was exported in CSV/Excel format for further analysis. Responses were counted and organised using Microsoft Excel, taking advantage of its filtering functions, pivot tables, and basic statistical formulas (such as counting, averaging, and percentages) to systematise the information and facilitate its interpretation. Open-ended responses were analysed using the AI tool Perplexity in the early stages of thematic exploration, as an auxiliary tool. A thematic analysis was conducted following the

Braun and Clarke (

2006) model, which allowed for the identification of recurring patterns in the responses and the construction of an interpretative narrative. This methodology involved several phases of work, including familiarisation with the data, generation of initial codes, search for themes, and review and cataloguing of these themes. Furthermore, the TAM approach was applied by incorporating questions related to motivations and resistance toward the use of AI, specific experiences with particular tools, and, more incisively, ethical and professional perceptions regarding the impact of AI on journalism.

To develop the qualitative component of the study, eight in-depth interviews were also conducted, based on a semi-structured script. These interviews enriched the analysis by providing deeper insight into areas where the quantitative data revealed controversy or divergence. The selection of participants was guided by a purposive sampling strategy, aimed at capturing a diversity of perspectives on the use of AI in journalism. Responses to the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into professional practice were categorised into the following three distinct attitudinal levels: negative, neutral, and positive. The negative response (divided into level 1, rejection, and level 2, distrustful use) was characterised by scepticism or outright rejection, often rooted in concerns about the erosion of journalistic integrity, the dehumanisation of storytelling, and the ethical risks associated with automation. The neutral response (divided into level 1, instrumental use, and level 2, passive acceptance) reflected a pragmatic acceptance of AI as a functional tool, typically used for efficiency in routine tasks, but without deep engagement or critical reflection on its broader implications. In contrast, the positive response (divided into level 1, basic acceptance and responsible use; level 2, critical integration; and level 3, leadership and innovation) encompassed a spectrum of proactive attitudes, ranging from responsible and ethical use to leadership in innovation. Journalists within this category not only integrate AI thoughtfully into their workflows, but also advocate for its ethical application, contribute to the development of newsroom standards, and actively participate in shaping the future of journalism through strategic and informed use of emerging technologies.

The selection criteria also considered professional roles, types of media outlets, and levels of engagement with AI tools, ensuring representation from different editorial contexts and technological experiences. By incorporating this range of voices, the study aims to reflect the complexity and plurality of journalistic attitudes toward AI and provide a more contextualised and ethically sensitive understanding of its adoption. This approach also responds to the ethical concerns documented in the literature, where journalists express uncertainty and caution regarding the implications of AI in news production.

The profiles of the eight journalists interviewed are detailed in

Table 1.

All interviews were transcribed to capture every detail of the recording and analysed to identify key parameters for this study, such as frequency of AI use in journalistic work, level of training or preparation, motives and reasons behind this use, position regarding the need for regulation and ethical implications, position on transparency and methods of disclosing AI use, and personal perspective on the future of AI in the field of journalism and challenges facing the media sector. Personal data from interviewees, as well as any information that could directly or indirectly identify them, were omitted to foster a climate of trust in the treatment of sensitive issues. In such situations, anonymity allows interviewees to express themselves more freely, without fear of professional repercussions or damage to their reputation.

4. Results

Numerous studies highlight the prodigious transformation of routines that is taking place in the field of journalism in the face of the unstoppable advance of AI. One of the issues that most concerns professionals and researchers is ethics, more specifically, the transparency of journalists and the media, the attribution of authorship, and the treatment and responsibility that should be given to AI tools.

In this paper, we analyse the results of a survey administered to fifty journalists working in newsrooms, with the aim of understanding their position on the use of AI and transparency in the media.

4.1. Actual Use of AI in Newsrooms

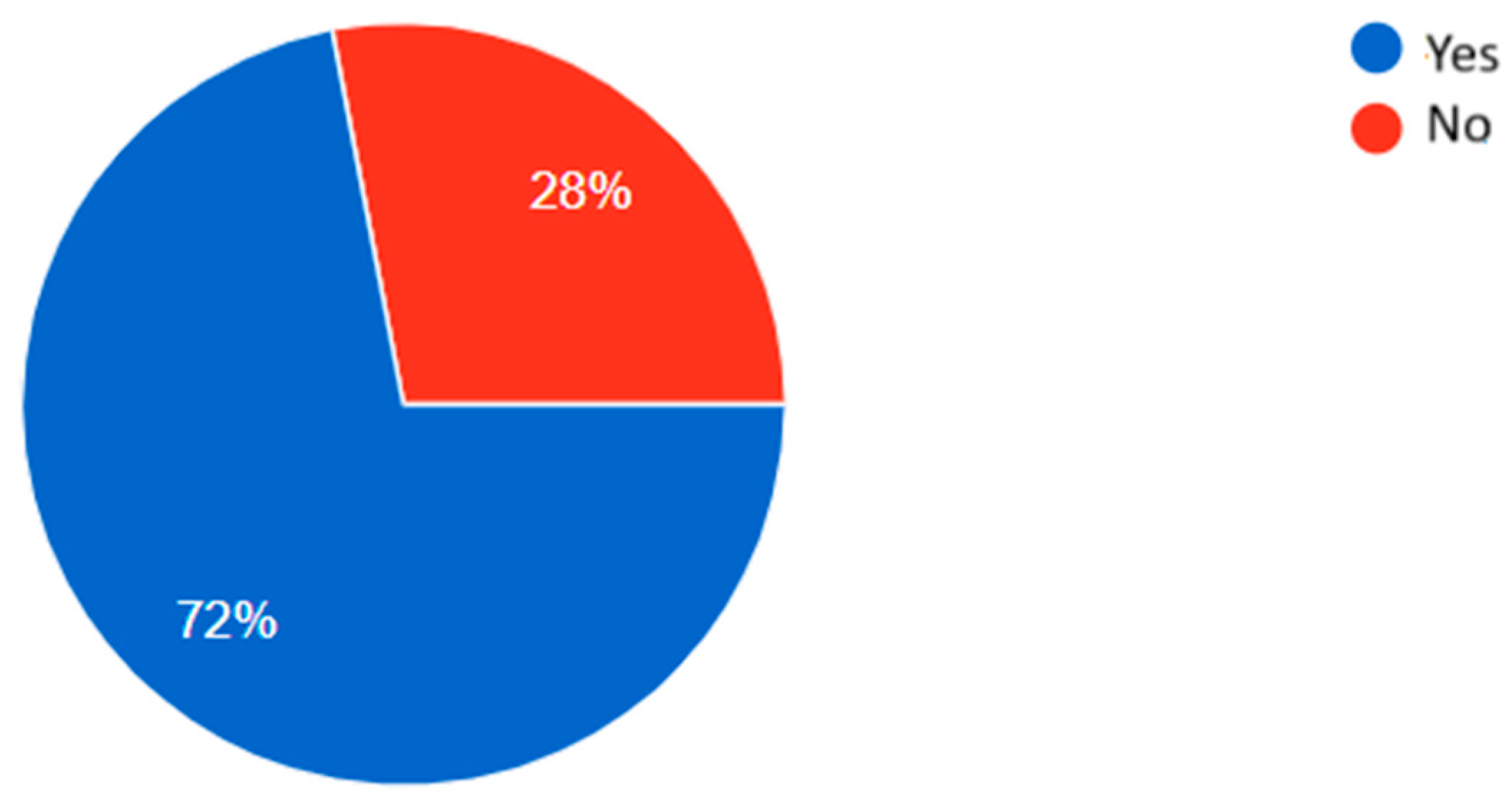

The results of the survey show that the use of AI tools is an everyday reality for most of the journalists surveyed. Specifically, 72% acknowledge having used some type of AI tool in tasks related to their journalistic work in the newsroom, while 28% have not used AI tools (

Figure 1).

Journalists who admit to having used AI tools, specifically 72% of those surveyed, mainly point to the following two tasks: translation (58.3%) and automatic content generation (e.g., GPT-3) (52.8%). This is followed, in order of importance, by assistance with writing and editing tasks (38.9%) and automatic summary generation (36.1%). Other tasks mentioned, although less frequently, include data analysis (36.1%), video and audio editing (19.4%), documentation tasks (5.6%), and audio transcription (2.8%). Therefore, these types of applications are used to assist journalists in their writing tasks, streamline news production, and enhance and enrich the editing and investigative journalism processes.

However, the interviews conducted reveal a very uneven degree of integration among journalists: some journalists use AI tools for occasional and ad hoc support in their production routines, while for others it is a regular tool. This frequency is impacted by various factors, such as age (the younger the journalist, the greater the use of AI tools) and specific training.

Interviewee 1, for example, uses AI daily and argues that ‘it can be used for complete content automation, from news production to the writing of sports reports and chronicles’. According to this interviewee, the main job of the journalist would be to ‘write very detailed instructions (instructions) for the AI to generate the content’, for which he acknowledges that the journalist must have a great background and deep knowledge of the subject matter. To get AI to reach an adequate level of writing, according to Respondent 1, ‘extensive and specific prompts (up to two pages long) that guide AI not only on the content but also on the syntactic structure (subject-verb-predicate, inverted pyramid) and style of the text, allowing the writer to have editorial control over the outcome’. A crucial aspect of this methodology is that it does not allow AI to select its own sources of information, but rather ‘it is the journalist himself who provides and narrows the necessary sources and data, which contributes to the veracity of the final product, preventing the system from drinking from unreliable sources’.

In addition to complete content automation, Interviewee 1 uses AI for other tasks, such as the transcription of audio (e.g., transcribing press conferences to obtain raw content), processing data from tables or PDF documents, and generating content from tables or PDF documents.

Interviewee 2, for his part, understands that the concept of AI is so broad that this umbrella can include, on the one hand, applications that can be of great use to journalists without entailing ethical conflicts, such as ‘the transcription of interviews, the conversion of audio files into text, which would be equivalent to the work carried out by a washing machine at home’, and, on the other hand, text generation applications that should not replace the very complex work carried out by journalists when they write a text. Interviewee 2, like the rest, considers that the journalist should, in any case, check the AI-generated content, even the transcriptions, as a particular expression used by the machine may give a different meaning to the one actually intended by the journalist.

Interviewees 3 and 8, along this line, recognise that AI has very useful applications for journalists, for example, for transforming press releases into news or for mechanical tasks, insofar as this optimises work time that the journalist can use to generate more exclusive information, allowing the medium to have a differentiated and quality news offer. Specifically, Interviewee 8 states that ‘it is useful for repetitive tasks, such as transcribing audio, editing video clips, or scheduling social media posts. Also for quick data searches or for summarising long reports. Tasks that do not require thinking like a journalist.’

Interviewee 5, who works at a local radio station, explains that, in his case, AI has been integrated into his daily routines on the radio, from searching for up-to-date information on the programme’s guests to reviewing the scripts for each show. Additionally, the generation of images and sounds adds extra value to programmes. In this regard, AI is used to design podcast cover art and compose melodies, without compromising the quality of the broadcast. Interview 7 also describes a use that is highly tailored to the outlet and the environment in which they work: “audio transcription, translation of texts in local languages, basic data analysis such as event statistics, and social media monitoring to detect trends. Also, for summarising long reports. However, final writing, in-depth analysis, and interviews should remain in the hands of the journalist.”

Interviewee 4 assures that he does not use AI tools in his work as a journalist and believes that ‘it should only be considered a positive tool for the journalist as an occasional support and in no case for editorial tasks’. In the same vein, Interviewee 6 expresses their rejection of incorporating AI into journalistic tasks and warns that ‘Its indiscriminate use can dehumanise journalistic storytelling, erode public trust, foster dependence on tools that do not understand context, and prioritise speed and volume over quality and truthfulness.’

4.2. Regulatory and Ethical Flaws

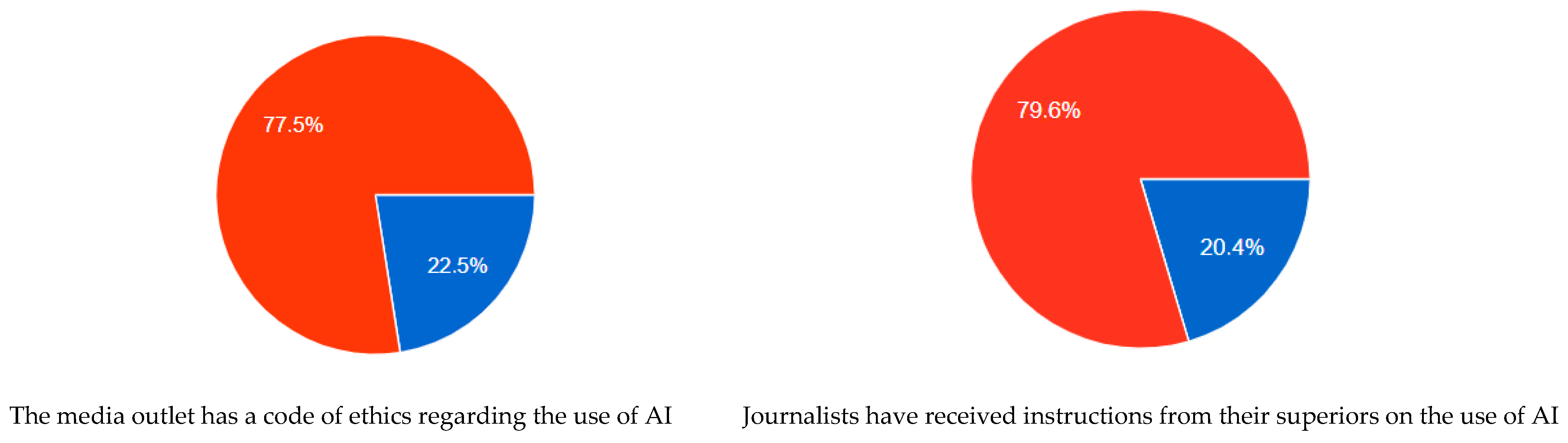

The survey data show that there is a significant gap in the internal regulation of the use of AI tools in the media. In fact, only a minority of respondents (20.8%) say that the media outlet where they work has specific ethical guidelines on the use of AI.

Most respondents have not received instructions from their media outlet (77.5%) (

Figure 2, left sphere) or their superiors (79.6%) (

Figure 2, right sphere) and point to the absence of protocols to manage the potential risks associated with automation, such as bias reproduction, loss of originality and style, ethical responsibility, and even the risk of misinformation. Despite this shortcoming, the data from the respondents show an almost unanimous consensus (94%) on the need for media organisations to have internal rules on the use of AI.

Most of the interviewees agree with this need and have not received instructions from their superiors or the media organisation where they work about the use of AI. Interviewee 2 suspects that this is due to the trust that the media places in journalists and their professionalism: self-regulation is trusted because it is part of the ethics that govern the principles of truthfulness with which journalists work, materialized in the SPJ Code of Ethics, promoted by the Members of the

Society of Professional Journalists (

2024), which, among other ethical considerations for journalists, includes the following: ‘Explain ethical choices and processes to audiences. Encourage a civil dialogue with the public about journalistic practices, coverage and news content.’

The most sought-after aspects of these rules are editorial responsibility (90%) and transparency (88%). Respondents also emphasise the protection of personal data (68%) and the prevention of algorithmic bias (70%).

Furthermore, in terms of the measures they believe should be taken to improve transparency, respondents prefer training and education in ethics and the use of AI (76%) and the publication of AI usage policies (76%).

Regarding the in-depth interviews, Interviewees 2, 4, 6 and 8 have not received any instructions from their superiors or their employer about the use of AI. Interviewee 4 insists that the need for AI has not been created because it is not commonly used. Interviewee 3 has some deontological guidelines and, in his environment, they have to declare the use of certain AI tools, while Interviewee 6 states that their outlet ‘does not have a specific ethical code for AI because there is an implicit trust that journalists will use their own judgment, although this is problematic since not everyone has the same level of knowledge or scruples.’

Interviewee 1 explains that ‘specific instructions are not really necessary in some media because the fundamental principles of journalism (truthfulness, contrast, responsibility) are already included in existing codes of ethics (such as FAPE).’ From his perspective, these codes are applicable regardless of the technology used to produce the information, so he sees no need to create specific regulations for AI, but rather to apply these existing principles.

Interviewee 5 does not believe that it is necessary to receive specific instructions within media organisations and considers AI to function as a software tool that reduces the time required for creation and research, enriching the journalistic creative process, which is inherently human.

4.3. Transparency and Attribution of Authorship

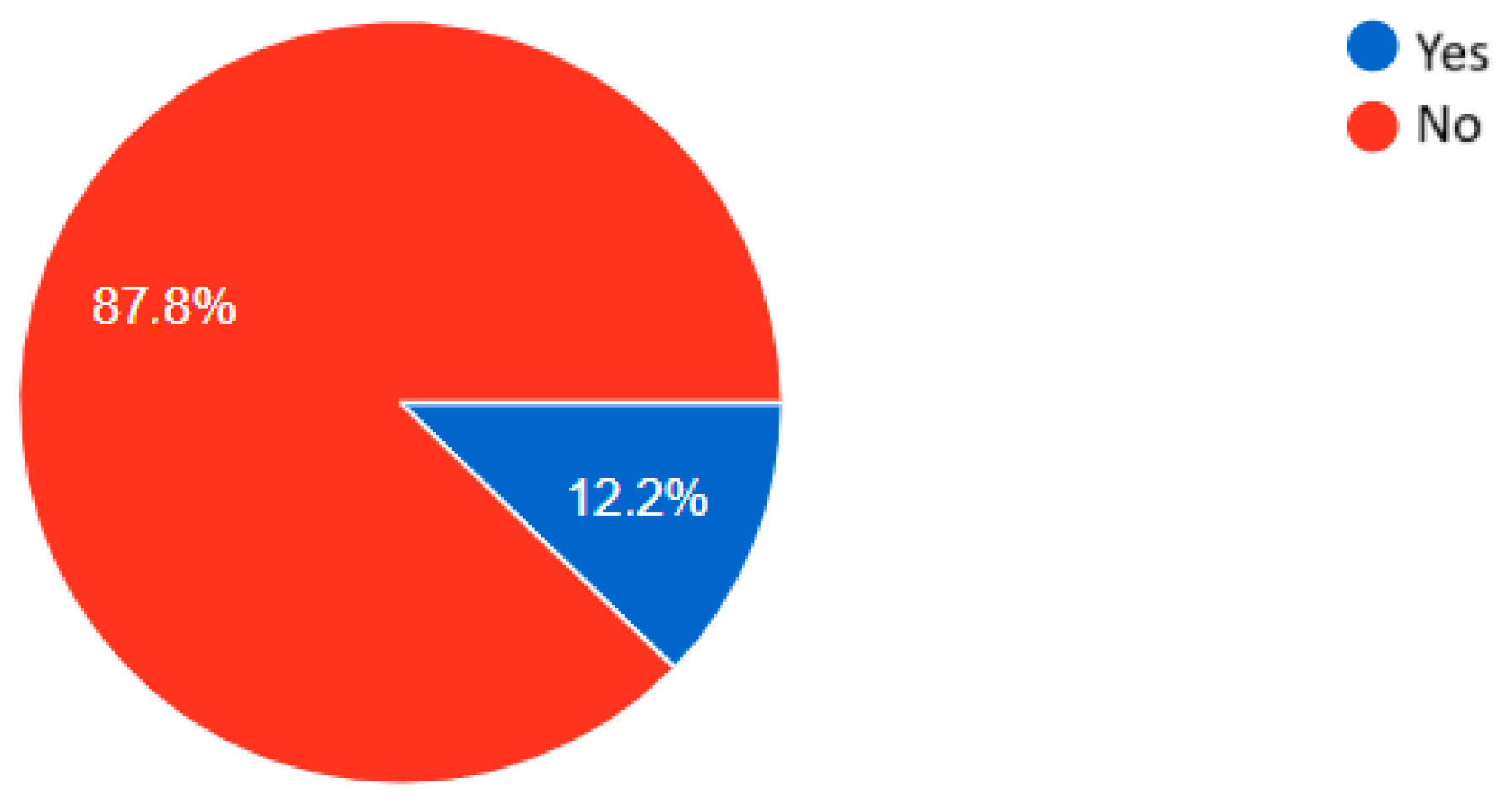

Transparency is one of the main challenges in the use of AI in journalism, according to this survey. Most of the journalists surveyed (87.8%) acknowledge that their media outlet does not require them to disclose the use of AI tools in editorial tasks, even if it is only used as an auxiliary tool. Only a small proportion of the respondents, specifically 12.2%, say that their media outlet requires journalists to disclose the use of AI (

Figure 3).

In the few cases where respondents mention the obligation to inform, only 10.8% do so with a specific, short, and forceful phrase, similar to the one mentioned by Kent in The Guardian, as follows: ‘This content has been produced with AI or with the help of AI’ or ‘News produced with AI under the supervision of an editor’.

When the use of AI is partial, supportive, and instrumental in nature, the respondents reveal that their organisations do not usually declare the use of AI. Only 11.1% of the respondents say that they recognise it, for example, in the case of translation or data collection. Most (88.9%) also do not cite the use of AI as a source.

Regarding authorship of the final text, there are no clear and consistent criteria among the respondents. If AI has been used partially in the writing of a text, the majority consider that the main author is still the journalist (65.1%); 27.9% consider that the author would be the media outlet and, to a lesser extent, 7% consider that the authorship would fall to the AI application. This plurality of criteria reflects the uncertainty that exists in the professional journalism sector with respect to the role that AI plays and will play in the process of generating journalistic content.

In relation to the in-depth interviews conducted, the majority of interviewees are in favour of declaring the use of AI, and even of attributing authorship to the AI application itself when it comes to automatically generated content, with the exception of Interviewees 1 and 8, who maintain a contrary and critical position on this trend regarding the need to declare AI use. Interviewee 1 argues the following on this matter: ‘AI should be considered a tool, like a calculator for a mathematician or a word processor for a writer, and not a source, so it would not be necessary to declare its use.’ In this sense, he questions the need to cite AI. As a consequence, he does not believe it is necessary for texts to state that AI has been used or which AI application(s) assisted the writer, since ‘the authorship rests entirely with the writer’. He maintains that ‘the journalist is the one who directs, verifies, and takes responsibility for the final content’. For Interviewee 1, the real ethical responsibility lies in the control that the journalist exercises over the process. As he is the one who selects and provides the sources for AI, he ensures that the system does not invent or use unverified information. In this way, the journalist maintains, at all times, the authorship and ultimate responsibility for what is published. AI is an instrument that executes his orders, and any error or bias in the final product is his responsibility as process supervisor. Interviewee 5 expresses a similar view, as follows: ‘AI use should only be disclosed to the same extent as the use of software related to audiovisual production’. It is a tool that is directed and programmed by a human being. Interviewees 4 and 7 consider declaration to be extremely necessary because the credibility of the journalist and journalism is at stake.

4.4. Demands and Proposals from the Sector

Regarding the changes that the journalists surveyed consider necessary to ensure the ethical and transparent use of AI in journalism, the open responses reveal a common concern. AI should be a support tool, but it should not replace journalists.

The respondents mainly call for more training and education (36.7%); clear internal media standards that allow honest action and media support (32.7%); and government regulations (18.4%). To a lesser extent, there is also a demand for collaboration between journalists and technologists (4.1%) and for professional associations to have the power to regulate and verify (2%), as other professional groups already do.

In response to an open question, 2% of the respondents said AI should not be used in journalism. The vast majority said that it should be used honestly, telling readers, listeners, or viewers how it was used, if at all.

The in-depth interviews reflect precisely the dichotomy of the survey: with clear rules and transparency, AI can be an ally for journalists; without regulation and without informing the audience, there is a risk of losing credibility and meaning.

In relation to the future, Interviewees 2, 4, and 6 believe that journalism training in AI should be promoted to avoid certain risks associated with its misuse, such as not providing ethical and rigorous information and, therefore, misinforming and even manipulating. However, as explained by Interviewees 2 and 7, regardless of how AI develops, the immediate future of the journalistic profession must be based on ethics and rigour, as with all technological advances. Interviewee 4 insists that ‘the reader’s trust derives from the sincerity of the journalist and how he accesses the information’. Interviewee 6 considers that ‘without a solid foundation in journalistic ethics and critical thinking, the use of AI can be counterproductive. Journalists must understand how these tools work, their limitations and biases, how to use them responsibly and not as a crutch’. Interviewee 8 explains that the journalist should review everything AI does, as follows: ‘You cannot blindly trust a machine. There must always be a human eye to ensure everything is correct’. Echoing this perspective, Interviewee 7 maintains the following: ‘All work involving AI must be carefully reviewed, data verified and context ensured.’ It is also important not to let AI write for us; it should only serve as a support tool. The greatest risk is misinformation if we do not thoroughly check what AI produces.’

Interviewee 3 believes that AI and journalism can go hand in hand as long as it is the production itself that feeds into AI and not the other way around. Furthermore, he does not believe that new regulations and ethical codes are necessary, as training can be translated into appropriate self-regulation. In this regard, Interviewee 5 believes that ‘AI should focus on mechanical processes, while humans must focus more than ever on the accuracy of their sources, critical thinking, and creativity’.

On the other hand, Interviewee 1 recommends journalists ‘to train and abandon fear, as AI is present and is advancing by leaps and bounds’. He believes that ‘adaptation is crucial for the journalist and that resistance to change will leave behind those who do not update’. He also argues that the future fundamental skill of the journalist will be the creation of prompts, as follows: ‘The ability to give precise, detailed and knowledgeable instructions to AI will be what differentiates quality work’. He even advocates the inclusion of subjects on prompt generation in communication faculties. But in his opinion, AI ‘does not replace the judgment, ethics, and structure of journalism’; in contrast, in-depth knowledge of these elements allows the journalist to guide the tool in an effective and responsible manner. Although he describes himself as ‘not very optimistic’, his vision is not apocalyptic. He sees the irruption of AI as a source of ‘opportunities’ for those who adapt, similar to the transformations caused by word processing and the Internet. He concludes that the in-depth knowledge of the journalistic profession (the ability to assess a news event, to structure a news story, and to apply ethical principles) will not only not disappear, but will be more crucial than ever. This background will be the indispensable raw material to be able to direct AI and generate reliable and quality content.

On the other hand, Interviewee 1 believes that the next logical step ‘will be total disintermediation, where AI not only summarises the content of the media, but generates the news directly for the user, completely bypassing the media as an intermediary’.

5. Discussion

The results of this study show that AI tools are widely used in newsrooms, although the frequency and intensity of their use vary depending on factors such as age, specific job roles, technological interests, and journalist training. These findings are consistent with previous research, such as that of

Mondría Terol (

2023), who identified the lack of training and professional resistance as key barriers to AI adoption, and

Manrique (

2023), who highlighted the coexistence of scepticism and experimentation in Spanish media outlets.

The findings of this study confirm that the integration of AI tools into Spanish newsrooms is widespread, albeit uneven in terms of frequency and depth of use. This variability is influenced by factors such as age, professional role, technological knowledge, and individual attitudes toward innovation. These results align with

Cools and Diakopoulos (

2024), who identified a broad spectrum of generative AI applications used in journalistic workflows, ranging from content creation and summarisation to distribution and personalisation. However, as in the Spanish context, their study also highlights that such integration is often guided by professional intuition rather than formal ethical frameworks.

The survey reveals the existence of a small sector of journalists reluctant to incorporate AI tools into their routines, arguing that journalistic work must remain original and human-driven, anticipating serious consequences for journalism resulting from the use and application of AI. Doubts about authorship, responsibility, and transparency generate mistrust. This tension between innovation and tradition is echoed by

Wu (

2024) and

Misri et al. (

2025), who describe journalists who navigate between the promise of technological enhancement and the preservation of core professional values such as verification, authorship, and editorial control. These dilemmas are not unique to Spain, but reflect broader global concerns about the ethical integration of AI in journalism.

A key finding is the lack of clear regulation on the use of AI tools. Journalists do not receive precise instructions from their media outlets or superiors, leading to reliance on personal judgment and self-regulation. This situation mirrors the findings of

Sonni et al. (

2024), who report that many journalists operate without formal guidelines, relying instead on informal norms and individual ethical reasoning. Although this autonomy may promote innovation, it also increases the risk of inconsistent practices and ethical missteps.

The literature review suggests that this regulatory vacuum is beginning to be addressed. At the European level, the AI Act introduces transparency and accountability requirements that could influence newsroom practices.

Parratt-Fernández et al. (

2025) identify a growing number of ethical documents and AI guidelines among European media organisations, although their implementation remains uneven. But the main professional codes of ethics in Spain have not yet incorporated specific rules to help the media take the right position, and the major media outlets are tentatively beginning to incorporate some rules into their style guides and codes of ethics.

El País (

Alcaide, 2025) has already incorporated some guidelines into its style book. This reality contrasts with the slowness of the media to regulate their newsrooms. There are timid private initiatives implemented by specific publications that include general recommendations on the need to preserve the critical sense of journalists and the commitment to improving the quality of journalism in a context that points to change.

The survey also highlights a significant gap between the actual use of AI and the absence of ethical protocols. This disconnect creates a climate of uncertainty, where journalists must rely on intuition and personal ethics, and audiences can question the originality and accuracy of news content. Comparative studies, such as those by

Cools and Diakopoulos (

2024), show that other European contexts, such as the Netherlands and Denmark, have adopted more structured and experimental approaches, suggesting that national media cultures play a role in shaping AI integration strategies.

This reliance on individual judgment underscores the urgent need for structured policies and training programmes that can support the responsible and transparent integration of AI technologies into journalistic practice. Although most professionals use these tools on an occasional and auxiliary basis, the vast majority of journalists are not currently required to declare their use. Most of the journalists surveyed recognise that there is no obligation in the media outlet where they work to report the use of AI tools in editorial tasks, even if used as an auxiliary tool.

Transparency emerges as a central concern. Most journalists surveyed report that their media outlets do not require disclosure of AI use, even when such tools are employed in editorial tasks. This lack of institutional transparency can undermine public trust and complicate accountability.

Kent (

2015) proposes practical alternatives to improve transparency, such as identifying sources, reviewing AI-generated content, and adapting style to maintain journalistic standards. However, recent studies by

Toff and Simon (

2025),

Jia et al. (

2024), and

Schell (

2024) argue that transparency must be multidimensional, incorporating procedural clarity and editorial agency rather than relying solely on labels.

The absence of clear regulations is also reflected in the diversity of opinions on authorship. While most respondents consider the journalist to be the main author when AI is used partially, others attribute authorship to the media outlet or the AI application. This plurality of views opens a debate on intellectual property and editorial responsibility, suggesting the possibility of shared authorship models depending on the degree of AI involvement.

Wu (

2024) reinforces this perspective by highlighting the role of individual agency and value-driven use in shaping AI adoption. An interesting debate could be opened on this issue, with implications for intellectual property and editorial responsibility. It also raises the question of possible shared responsibility, even as a percentage basis, depending on the level of AI use.

Journalists express a strong commitment to transparency and ethical responsibility. They advocate for declaring AI use, citing it as a source when relevant, and ensuring editorial oversight. These proposals align with broader calls for algorithmic literacy and ethical training, as highlighted by

FleishmanHillard (

2024) and

Cools and Diakopoulos (

2024). Respondents also stress that AI should support, not replace, journalists, helping to enhance content quality while preserving human creativity and critical thinking.

The profession is undergoing a redefinition in response to technological change. In this sense,

Simon’s (

2024) report highlights the tension between efficiency and journalistic quality. Although AI can optimise workflows, it does not guarantee improved information quality. Automated content production requires human oversight, professional standards, and an institutional context that maintains journalistic values. The future role of journalists may evolve toward prompt engineering and ethical supervision, where the ability to guide AI tools effectively becomes a core competency. Although challenging, this will offer opportunities to strengthen journalistic integrity and public trust, provided that it is accompanied by robust ethical frameworks and a renewed commitment to transparency.

The impact of AI on journalism is a reality that cannot be ignored or sidestepped, but, to a large extent, the credibility of the profession and the media will depend on the proper use of these tools and the regulatory and ethical framework that is established, so journalists have validated criteria that allow them to use AI tools without losing their central creative role.

The sample of this study could be expanded to other countries to obtain more accurate results from the European landscape, although the limitations of the population and the rapid changes that journalists and the media are experiencing in terms of the use of AI tools and the adoption of regulatory measures would have to be taken into account. Comparative studies between different geographical areas could also be developed, making it possible to identify cultural and professional differences and assess the degree of technological implementation. It would also be possible to compare different regulatory frameworks and analyse public perceptions of the use of AI by journalists.

6. Conclusions

This research confirms that the use of AI tools as auxiliary instruments in Spanish newsrooms is widespread, although their recurrence and implementation remain uneven. Factors such as age, specific training, and conceptual mistrust of AI influence this variability. However, beyond descriptive data, the study reveals a deeper structural and ethical tension within journalistic practice.

One of the most significant insights is the disconnect between the actual use of AI and the lack of ethical and regulatory standards. Journalists operate in a context of normative ambiguity, often relying on personal judgement and self-regulation. This situation not only affects editorial consistency, but also raises concerns about transparency, authorship, and accountability, core values that are being redefined in the digital age.

Transparency emerges as a central concern. The absence of institutional requirements to disclose AI use reflects a broader reluctance to engage with the ethical implications of automation. This lack of disclosure can undermine public trust and complicate editorial responsibility. The diversity of professional opinions on authorship, whether attributed to the journalist, the media outlet, or the AI system, further illustrates the conceptual uncertainty surrounding hybrid content creation. This disparity of criteria highlights the opportunity to open a new debate on this issue, which falls squarely within the realm of intellectual property and editorial responsibility.

In this context of digital transformation, journalism is undergoing a process of redefinition. Journalists advocate for AI to remain a support tool, not a substitute, and express a strong commitment to transparency and ethical responsibility. Their proposals, such as declaring AI use, promoting AI literacy, and establishing internal guidelines, point to a roadmap for responsible integration.

Through in-depth interviews, critical perspectives have also been found, framing AI not as a source or co-author, but as an advanced tool at the service of the journalist. This view challenges the prevailing trend toward mandatory disclosure and is based on the argument that citing the use of AI is unnecessary, analogous to not citing a calculator or a word processor. Therefore, the focus of ethical responsibility shifts from statement to process. The journalist’s job is to exercise rigorous control over the sources of information he or she provides to the system and to verify the veracity and consistency of the end result. Under this model, authorship and ultimate responsibility fall unequivocally on the human professional, who acts as a supervisor and guarantor of published content.

In line with this approach, the creation of new AI specific ethical codes would be redundant, as the fundamental principles of journalism, truthfulness, contrast, and accountability, already enshrined in existing ethical codes, are timeless and technologically agnostic. The challenge would not lie in the drawing of new regulations, but in applying existing principles to the new technological context. It would also imply redefining the role of the journalist, who would evolve from a mere creator of texts to an architect of prompts and supervisor of the final product, where the ability to formulate precise and well-founded instructions would become the core competency to ensure that AI operates within established ethical and professional boundaries.

Although the study is geographically limited to Spain and is based on a relatively small sample, it nevertheless provides valuable information on the ethical and professional dynamics surrounding the use of AI in journalism. These findings offer a meaningful foundation for future comparative research and broader investigations across different media systems. Furthermore, the rapid evolution of AI tools and newsroom practices suggests that attitudes and regulations may change in the near future. Comparative studies between countries and longitudinal research would be valuable to assess cultural differences and track changes over time.

Ultimately, the credibility of journalism in the age of AI will depend on the profession’s ability to integrate these tools ethically and transparently. Journalists and media organisations must establish clear and consistent criteria that preserve editorial autonomy and reinforce public trust. Through this study, journalists outline a preliminary roadmap to transparency, including commitments to ethical oversight, training, and institutional accountability.

It would also be interesting to open a debate about the growing technological dependence of media organisations, as

Simon (

2024) points out, and to reflect on the risks of information power concentration and the need to preserve journalistic independence from external technological interests.