Aiming Close to Make a Change: Protest Coverage and Production in Online Media as a Process Toward Paradigm Shift

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Press–Protester Relations and Coverage of Protests by Legacy Media

2.2. Protests and Social Media

3. Theoretical Background

Polysystem Theory

4. Research Questions

- How was the Balfour Protest covered in the mainstream online press and presented by social movements and regular protesters on social media?

- How do the leaders of the Balfour Protest present and explain their conduct and media use?

- How can the media coverage and the relationship between the online press and social media be theoretically explained?

5. Methodology

6. Findings

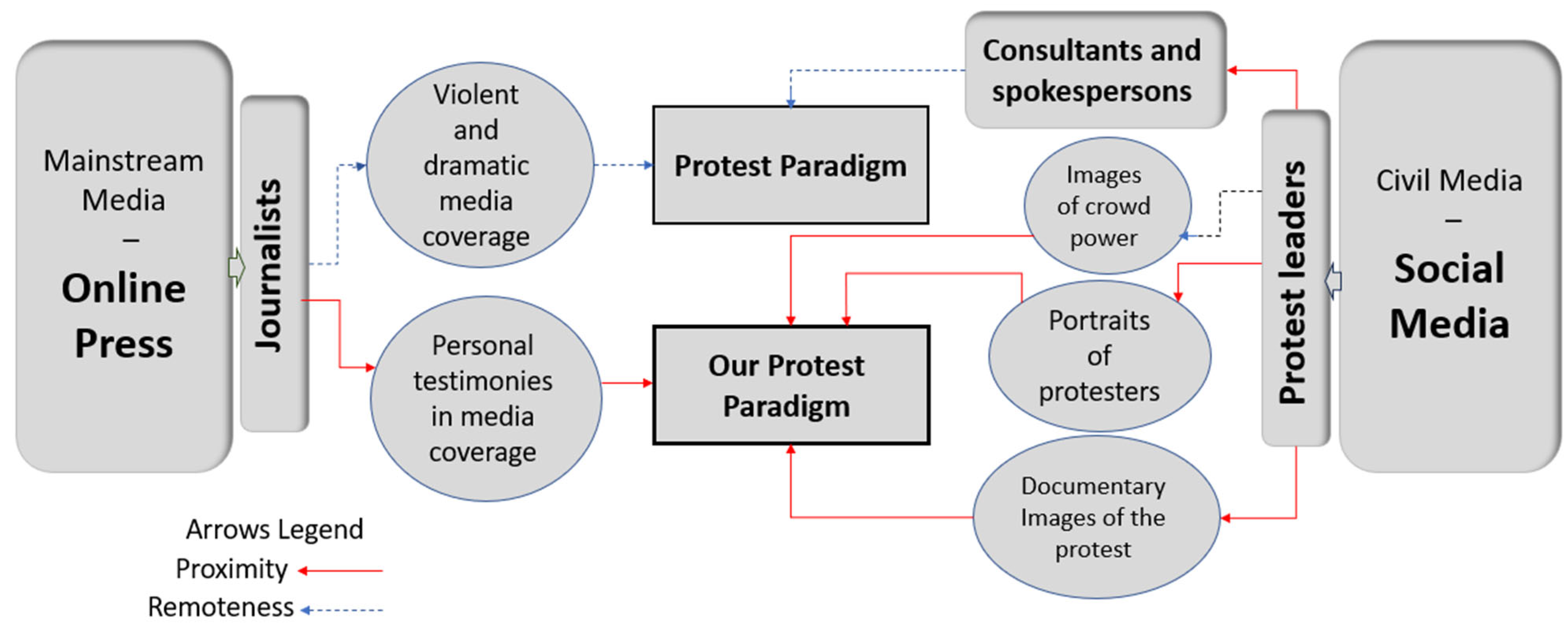

6.1. Coverage of the Protest in the Online Press—Between Proximity and Remoteness

6.1.1. Look at Them—Warlike Discourse and Violence in the Streets

6.1.2. Hear Them—Personal Testimonies from the Street

6.2. Coverage on Social Media—Between Proximity and Remoteness

6.2.1. See and Hear Us—Portraits of Protesters on Social Media

6.2.2. Look at Our Strength—Remote Images Expressing the Protesters’ Power

6.3. Long Live Social Media: Protest Leaders Reject Mainstream Media

6.4. Is the Mainstream Media Still Relevant? Spokespersons and Consultants as Conservation Agents

7. Discussion: Toward a Paradigm Shift?

7.1. Changing Representation: Testimonies, Portraits, and Accountability

7.2. Changing Perception: A Rigid Encounter of Two Different Media Systems

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aharoni, M. (2020). To shame and not to be ashamed: A repertoire of civil tactics on the subject of sexual abuse on the social network. Social Issues in Israel, 29(1), 41–84. [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni, M. (2022). When mainstream and alternative media integrate: A Polysystem approach to media system interactions. Television and New Media, 24(6), 691–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharoni, M., & Roth-Cohen, O. (2024). Web-series ads as a new marketing media: Toward a commercial-independent digital integration model. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaihani, Y., & Shin, J.-H. (2022). News agenda setting in social media Era: Twitter as alternative news source for citizen journalism. In J. H. Lipschultz, K. Freberg, & R. Luttrell (Eds.), The emerald handbook of computer-mediated communication and social media (pp. 233–249). Emerald. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, P., & Lichbach, M. (2003). To the Internet, from the Internet: Comparative media coverage of transnational protests. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 8(3), 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, E., Caren, N., Olasky, S. J., & Stobaugh, J. E. (2009). All the movements fit to print: Who, what, when, where, and why SMO families appeared in the New York Times in the twentieth century. American Sociological Review, 74, 636–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angier, R. (2015). Train your gaze. AVA Publishing SA. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Zachary, A., Hasson, N., & Shizaf, H. (2020, October 5). Thousands of Israelis joined the protest on Saturday for the first time. 17 of them explain why exactly now. Country. Haaretz. Available online: https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/protest2020/2020-10-05/ty-article-magazine/.premium/0000017f-e4b6-dc7e-adff-f4bf09b00000 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Boesman, J., & Costera Meijer, I. (2018). Nothing but the facts? Journalism Practice, 12(8), 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzon, A. (2015). Dancing in the streets: On the twilight zone between media and social protests. Resling. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broersma, M., & Eldridge, S. A. (2019). Journalism and social media: Redistribution of power? Media and Communication, 7(1), 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Porta, D. (2013). Clandestine political violence. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Earl, J., McKee Hurwitz, H., Mejia Mesinas, A., Tolan, M., & Arlotti, A. (2013). This protest will be tweeted: Twitter and protest policing during the Pittsburgh G20. Information, Communication & Society, 16(4), 459–478. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, R. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even-Zohar, I. (1990). Polysystem theory. Poetics Today, 11, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even-Zohar, I. (2010). Papers in culture research. Tel Aviv University. [Google Scholar]

- Felman, S., & Laub, D. (1992). Testimony: Crises of witnessing in literature, psychoanalysis, and history. Taylor & Frances/Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Friedson, Y., Goldich, C., & Cohen, G. (2020, July 15). Fifty arrested in violent clashes after the demonstration near the Prime Minister’s residence: “Anger that was not there until now”. Ynet. Available online: https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/SkB5EYokv (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Frosh, P., & Pinchevski, A. (2009). Media witnessing: Testimony in the age of mass communication. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gamson, W., & Wolfsfeld, G. (1993). Movements and media as interacting systems. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 528, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, R. (2018). Photographing citizens. Key, 12, 149–174. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin, T. (1980). The whole world is watching: Mass media in the making & unmaking of the new left. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, S. (2019). Framing #Ferguson: A comparative analysis of media tweets in the US, UK, Spain, and France. International Communication Gazette, 81(6–8), 623–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, T. (2021). Polysystem theory: A versatile, supra-disciplinary framework for the analysis of culture and politics. In D. Souto, A. Sampedro, & J. Kortazar (Eds.), Circuits in motion: Polysystem theory and the analysis of culture (pp. 32–41). Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx, J. (2021). The rise of social journalism: An explorative case study of a youth-oriented instagram news account. Journalism Practice, 17(8), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx, J., & Vázquez-Herrero, J. (2024). Dissecting Social Media Journalism: A Comparative Study Across Platforms, Outlets and Countries. Journalism Studies, 25, 1053–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, T. (1996). From the bottom up: Social movements and political protest. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H., Clinton, K., Purushotma, R., Robison, A. J., & Weigel, M. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st Century. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jonisová, E. (2019). Portrait—Visual identity of a person. European Journal of Media, Art & Photography, 7(2), 98–131. [Google Scholar]

- Katriel, T. (2020). Defiant discourse: Speech and action in grassroots activism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E. (2014). Back to the street: When media and opinion leave home. Mass Communication and Society, 17(4), 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S. (2021, February 11). Digital 2021: Israel. Datareportal. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-israel (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Lee, F. L. F. (2014). Triggering the protest paradigm: Examining factors affecting news coverage of protests. International Journal of Communication, 8, 2725–2746. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. J., & Lee, J. (2023). #StopAsianHate on TikTok: Asian/American women’s space-making for spearheading counter-narratives and forming an ad hoc asian community. Social Media + Society, 9(1), 205630512311575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman-Wilzig, S. (1992). Public protest in Israel: 1949–1992. Bar-Ilan University. [Google Scholar]

- Lemelshtrich Latar, N., Aharoni, M., & Poppel, M. (2021). Israel: The importance of alternative media as a media accountability instrument. In S. Fengler, T. Eberwein, & M. Karmasin (Eds.), The global handbook of media accountability (Chapter 22, pp. 237–246, ISBN 9780367346287). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, L. (2020, August 28). Acting commissioner of police on the allegations of violence against demonstrators: “The discourse against us borders on incitement. Walla! Available online: https://news.walla.co.il/item/3383273 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Literat, L., Boxman-Shabtai, L., & Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2022). Protesting the protest paradigm: TikTok as a space for media criticism. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 28(2), 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margetts, H., John, P., Hale, S., & Yasseri, T. (2016). Political turbulence: How social media shape collective action. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Masullo, G. M., Brown, D. K., & Harlow, S. (2024). Shifting the protest paradigm? Legitimizing and humanizing protest coverage lead to more positive attitudes toward protest, mixed results on news credibility. Journalism, 25(6), 1230–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsa, K. E. (2023, November 15). More Americans are getting news on TikTok, bucking the trend seen on most other social media sites. Editor & Publisher. Available online: https://pewrsr.ch/49Er7sE (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- McCarthy, J. D., McPhail, C., & Smith, J. (1996). Images of protest: Dimensions of selection bias in media coverage of Washington demonstrations, 1982 and 1991. American Sociological Review, 61(3), 478–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, C., & Rossi, L. (2018). Images of protest in social media: Struggle over visibility and visual narratives. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4293–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (2023). Reuters institute digital news report 2023. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, I., Fung-Yee Choi, S., & Lih-Shing Chan, A. (2023). Resistance to ‘framing’? The portrayal of asylum seekers and refugees in Hong Kong’s online media. Journalism Practice, 17(7), 1537–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perach, R. (2022). Survey of news consumption patterns 2022. The Second Authority for Television and Radio. Available online: https://www.rashut2.org.il/media/1937/%D7%A1%D7%A7%D7%A8-%D7%A6%D7%A8%D7%99%D7%9B%D7%AA-%D7%97%D7%93%D7%A9%D7%95%D7%AA-2022-%D7%98%D7%9C%D7%95%D7%99%D7%96%D7%99%D7%94-%D7%95%D7%A8%D7%93%D7%99%D7%95.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Poell, T., Abdulla, R., Rieder, B., Woltering, R., & Zack, L. (2016). Protest leadership in the age of social media. Information, Communication & Society, 19(7), 994–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poell, T., & van Dijck, J. (2015). Social media and activist communication. In C. Atton (Ed.), The Routledge companion to alternative and community media (pp. 527–538). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Poell, T., & van Dijck, J. (2018). Social Media and New Protest Movements. In J. Burgess, A. Marwick, & T. Poell (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media (pp. 546–561). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rafail, P., Walker, E. T., & McCarthy, J. D. (2019). Protests on the front page: Media salience, institutional dynamics, and coverage of collective action in the new york times, 1960–1995. Communication Research, 46(1), 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A. V. (2017). Bearing witness while black: Theorizing African American mobile journalism after Ferguson. Digital Journalism, 5(6), 673–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A. V. (2024). Social media, citizen reporting, and journalism: Police killing of George Floyd, 2020. In J. V. Pavlik (Ed.), Milestones in digital journalism (pp. 71–88). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Roeh, I. (1994). Differently on communication: Seven openings to examine media and newspapers. Reches. [Google Scholar]

- Rucht, D. (2004). The Quadruple ‘A’: Media Strategies of Protest Movements since the 1960s. In W. van de Donk, B. D. Loader, P. G. Nixon, & D. Rucht (Eds.), Cyberprotest: New media, citizens and social movements (pp. 29–56). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, S., Zheng, P., Strum, H. A., & Fadnis, D. (2016). Protesting the paradigm? A comparative study of news coverage in Brazil, China, and India. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(2), 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharir, M. (2020, September 27). The same slogans, but as if on thin ice: From the convoy to Paris Square. Haaretz. Available online: https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/protest2020/2020-09-27/ty-article-magazine/.premium/0000017f-db95-d3ff-a7ff-fbb53d9d0000 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Vázquez-Herrero, J., Negreira-Rey, M. C., & López-García, X. (2020). Let’s dance the news! how the news media are adapting to the logic of TikTok. Journalism, 23(8), 1717–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodevsky, O., Walter, D., Levy, E., & Lila, E. (2012). “The protest is back—(only) thousands came”: Coverage of the social protest in the Israeli press. Keshav.

- Von Nordheim, G., Boczek, K., & Koppers, L. (2018). Sourcing the sources. Digital Journalism, 6(7), 807–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfsfeld, G. (1984). Symbiosis of press and protest. An exchange analysis. Journalism Quarterly, 61(3), 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfsfeld, G. (2011). Making sense of media and politics: Five principles in political communication. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yaron, L. (2020, September 1). Proud citizens: What causes the LGBT community to move in large numbers to Balfour? Haaretz. Available online: https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/protest2020/2020-09-01/ty-article-magazine/.premium/0000017f-dbab-db5a-a57f-dbebe5780000 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aharoni, M. Aiming Close to Make a Change: Protest Coverage and Production in Online Media as a Process Toward Paradigm Shift. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020078

Aharoni M. Aiming Close to Make a Change: Protest Coverage and Production in Online Media as a Process Toward Paradigm Shift. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(2):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020078

Chicago/Turabian StyleAharoni, Matan. 2025. "Aiming Close to Make a Change: Protest Coverage and Production in Online Media as a Process Toward Paradigm Shift" Journalism and Media 6, no. 2: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020078

APA StyleAharoni, M. (2025). Aiming Close to Make a Change: Protest Coverage and Production in Online Media as a Process Toward Paradigm Shift. Journalism and Media, 6(2), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020078