2. Materials and Methods

In this study, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the content and underlying context of Russian media narratives concerning Latvia, Poland, and Serbia. For the content analysis, we selected RIA Novosti, one of the most influential Russian news agencies. This analysis enabled us to determine how the portrayal of these countries is shaped for Russian audiences—how their domestic and international challenges are depicted and linked to the security concerns of the Russian Federation.

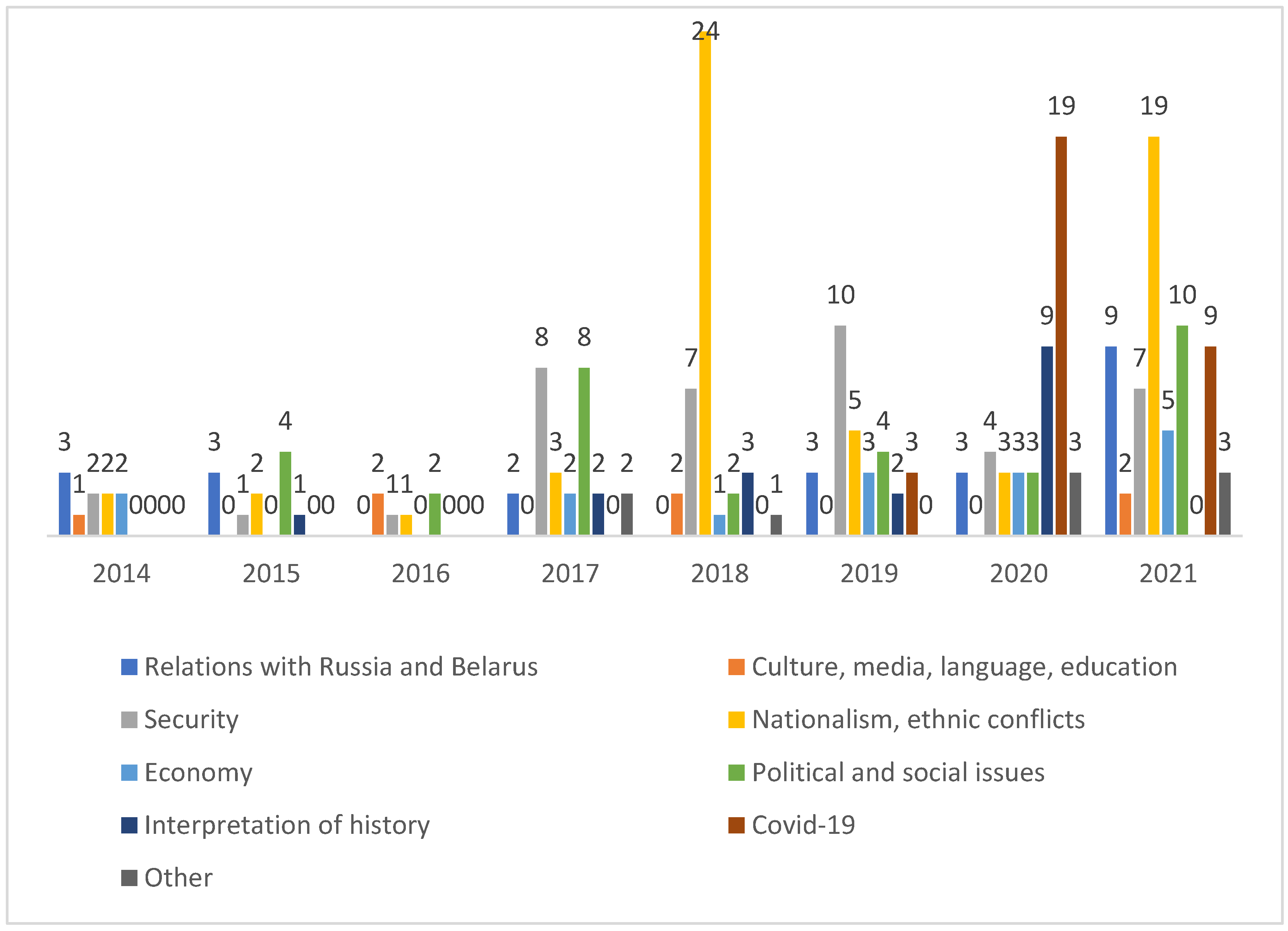

We examined all materials published on the RIA-Novosti website between 1 January 2014 and 16 October 2021 relating to the countries under consideration. In total, we analysed 170 media items concerning Latvia, 419 concerning Poland, and 235 concerning Serbia. Content analysis and contextual analysis were applied separately to each item. The media materials were examined with regard to both their content and their tone in relation to the countries they reference. We identified eight principal content categories: (A) relations with Russia and Belarus; (B) culture, media, language, and education; (C) security; (D) nationalism and ethnic conflicts; (E) economics; (F) political and social issues; (G) interpretation of history; and (H) the COVID-19 pandemic. In the case of Poland, we included an additional, ninth category: (I) Polish-Ukrainian relations. Materials that could not be classified under these headings were assigned to a tenth category: (O) other. A particular characteristic of Russian state-controlled media, which functions as a tool of propaganda, is the high degree of emotional and evaluative content, coupled with a virtual absence of neutral, fact-based reporting. Bearing this in mind, we also assessed the tone adopted by the agency in its portrayal of the three countries under analysis. A negative tone was understood to be present when the materials highlighted weaknesses in the political and economic spheres of these countries, social difficulties, and, above all, the policies of their respective governments, especially when such policies were characterised as anti-Russian. This includes, in particular, actions such as the imposition of sanctions on the Russian Federation or the refusal to recognise its activities, most notably the occupation and illegal annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol. Agency materials that adopt a critical stance towards the historical narratives of these countries, especially those alleging collaboration with Nazi Germany during the Second World War, were also classified as exhibiting a negative tone. Conversely, materials were considered to possess a positive tone when they presented favourable aspects of the political, economic, and social life of these countries, or emphasised the significance of their bilateral ties and cooperation with Russia, both in historical and contemporary contexts. A full list of the sources, including their publication dates and links, as well as their topics, can be found in the

Supplementary Material accompanying this article.

The article is structured into seven main sections. Apart from the Introduction (

Section 1) and Materials and Methods (

Section 2),

Section 3 presents a discussion in contemporary literature on how Russian media can influence the creation of an enemy image, and

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6 analyse the ideological context of Russian state media activities and development in the period 2014–2021 and the results of our survey.

Section 4 outlines key issues related to the dissemination of information and the role of the media in contemporary Russian security policy.

Section 5 presents the findings of a content analysis of RIA Novosti reports on selected Central and Eastern European countries from 2014 to 2020.

Section 6 provides a discussion of these findings. Finally, the Conclusions (

Section 7) asserts that state-controlled media constitute a fundamental component of Russia’s current security policy. There is a clear correlation between the strategic objectives of the Russian state in the sphere of information and the content disseminated by the media. Given the increasing international and domestic challenges facing Russia, it is likely that the role of state-controlled media will become even more pronounced. Consequently, efforts to restrict information dissemination in Russia—already evident—will be increasingly codified in law and persist until Russian society is effectively isolated from independent sources of information.

The research presented in this article is not without its limitations. The analysis has primarily concentrated on examining Russian media as an instrument for advancing the objectives of the Russian information security policy in the period preceding the Russian-Ukrainian war, and within the broader context of Russia’s prolonged confrontation with, and isolation from, the West. It is our view that the data gathered in this study may serve as a foundation for more detailed analysis of the rhetorical strategies employed in Russian media to incite or sustain specific sentiments and attitudes within Russian society. Such analysis could further explore the linguistic variation and evolution of media discourse, taking into account the particular country under discussion and the shifting priorities of Russian foreign and security policy.

3. How Russian Media Influence the Construction of an Enemy Image

Contemporary means of mass communication enable the dissemination of messages across borders more easily and cost-effectively than ever before, with social media serving as the most illustrative example). Since the annexation of Crimea, the intensification of propaganda both within Russia and abroad has become a defining feature of its confrontation with the West (

Pugačiauskas, 2017, p. 101). Russian media frequently depict Western countries as adversaries of Russia—this includes both Western European states and former Soviet republics such as the Baltic countries. As Ralf Roloff and Pál Dunay observe (

Roloff & Dunay, 2018, p. 21), the Soviet Union engaged in propaganda as an international ally; however, owing to its lack of credibility, it found success only in regions where such propaganda was supported by military force. In contrast, the Russian Federation now employs a diverse range of communication strategies tailored to various audiences. Roloff and Dunay stress the importance of cost-efficiency, which accounts for Russia’s preference for electronic media, including social media and television. Before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russian state television was widely accessible across the former Soviet republics, including the Baltic states. The influence of Russian television was reflected in public opinion polls, which indicated higher levels of sympathy for the Russian Federation and endorsement of Russian viewpoints in areas where its television programmes were available. Even prior to 2022, the Russian Federation disseminated its narratives online via a multitude of platforms and social networks. When these platforms were compromised or discredited, they were swiftly replaced by new, ostensibly more reliable ones. In the print media sector, which had a comparatively limited public impact, Russia facilitated access for foreign journalists sympathetic to its regime. These journalists were provided with interviews with Russian officials and a curated Russian perspective on events, often in multiple languages. Improvements in translation quality may indicate Russia’s strategic investment in this domain. This approach leveraged the time constraints faced by Western journalists, who frequently relied on pre-packaged information without independent verification. As a result, Russian narratives were reproduced in foreign media outlets (

Roloff & Dunay, 2018, pp. 22–23).

Russia further capitalises on the internal coherence of its messaging, which contrasts starkly with the fragmented media landscape of the West. This situation is exacerbated by information overload, making it increasingly difficult for audiences to discern reliable sources. In the age of social media, traditional modes of communication have become obsolete, and messages now reach foreign populations with unprecedented ease. Roloff and Dunay (

Roloff & Dunay, 2018, pp. 23–24) highlight three key points: (1) social media has reduced the cost of reaching target audiences and increased the affordability of influence; (2) messages can be more precisely tailored to specific demographic groups; and (3) platforms such as Facebook amplify confirmation bias by presenting users with content aligned with their previous engagements or browsing history, reinforcing pre-existing beliefs. As the authors note, the Russian Federation has adeptly exploited the contrast between its tightly controlled media environment and the West’s commitment to freedom of speech and media. It takes advantage of this asymmetry, benefiting from the openness of Western media markets while maintaining near-total control over its domestic media landscape.

The Russian Federation continues to increase its investment in information warfare, thereby eroding the comparative advantage historically held by Western media. Roloff and Dunay argue that the key difference between Soviet and contemporary Russian media is not structural, but strategic—today’s media is fully integrated into Russia’s broader geopolitical objectives. The principal aim is not persuasion but the cultivation of doubt regarding other international actors and the assertion of influence over foreign societies and governments. Russia also exploits the West’s ethical imperative to preserve freedom of expression, while enforcing a domestic media monopoly and systematically eliminating independent media (

Roloff & Dunay, 2018, p. 19).

Through its state media, the Russian Federation promotes pro-Kremlin messages both domestically and internationally. In her analysis of political trust and Russian media in Latvia, Ieva Berzina (

Berzina, 2018, pp. 7–8) argues that the influence of Russian media must be considered within the broader context of national political and economic conditions. She concludes that Russian media activities may primarily aim to undermine the legitimacy and achievements of other states, thereby reducing political trust. According to

Bokša (

2019, p. 1), the Russian Federation exploits public distrust in media institutions. Even before 2022, Central-Eastern Europe was viewed as particularly vulnerable to disinformation, in part due to declining trust in traditional media and a corresponding rise in reliance on social media. This shift heightens susceptibility to misinformation, particularly during periods of heightened political tension. The disinformation campaign against Ukraine intensified following the Maidan and the annexation of Crimea. Since the launch of full-scale aggression in 2022, this campaign has become a central focus of Russian state media, which now constructs an alternative reality in which the aggressor is portrayed as the victim (

Spahn, 2023, p. 65). Russian propaganda and disinformation routinely blame Ukraine, the United States, and NATO for the war (

Musiał-Karg & Łukasik-Turecka, 2023). Soviet-era propaganda tropes are revived, including narratives of cultural conflict and isolation from the West, as well as the invocation of the anti-fascist legacy of World War II, now projected onto alleged fascist elements in Ukraine and elsewhere. As Susanne Spahn notes (

Spahn, 2023, p. 65), the imperial aspirations of the Russian Federation, reminiscent of the Stalinist period, now manifest in the vision of a Russian-led Eurasian empire.

In March 2022, in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the European Union banned the distribution of content from Russian state-affiliated media such as Sputnik and Russia Today (RT), including their subsidiaries. Nevertheless, certain Kremlin-funded outlets continue to operate online (

Spahn, 2023, pp. 48–49). In the German-speaking online sphere, and among Russian-speaking communities in Germany, pro-Russian propaganda continues to circulate. Spahn identifies seven recurring narratives: (1) the fight against fascists; (2) the denial of Ukraine’s national identity; (3) the liberation of Ukrainians from Nazis; (4) the West’s supposed war against Russia; (5) the depiction of the West as decadent and weak; (6) Russia’s role as a Eurasian empire; and (7) the assertion that Western support for Ukraine will lead to the West’s downfall. According to the Integration Barometer 2020 of the German Expert Council on Integration and Migration, approximately one-quarter of repatriates from the former Soviet Union, the largest group of Russian speakers in Germany, trust Russian media sources (

Spahn, 2023, p. 50).

Dariia Rzhevska and Victoria Kuzmenko (

Rzhevska & Kuzmenko, 2023, p. 210) similarly underscore the significance of disinformation in advancing Russia’s strategic objectives. They argue that the Russian Federation has long employed disinformation as a deliberate strategy to propagate anti-democratic narratives. This disinformation model relies on numerous channels, shows no reluctance in promoting blatant falsehoods, and employs rapid, repetitive dissemination without concern for internal consistency. Key methods include outright lies, fact distortion, defamation, distraction, provocation, and historical revisionism. The Russian Federation’s substantial investment in communication infrastructure further enhances the impact of these strategies. According to Rzhevska and Kuzmenko, Russian media are unconcerned with factual accuracy and actively manufacture narratives that serve the regime’s political interests.

4. Media and Security Policy in Contemporary Russian Discourse

The prevailing view among scholars examining the significance of the media—and, more broadly, the transmission of information—in state security policy is that the process of the mediatisation of warfare, and consequently the increased role of the media in security policy, began with the 1991 Gulf War (

Peoples & Vaughan-Williams, 2015, pp. 188–189). A new mode of reporting on hostilities made warfare perceptible to millions of media consumers worldwide. The mediatisation of conflict also contributed to the securitisation of various aspects of social and political life, even where their connection to security issues may not initially seem apparent. In this way, securitisation exerts a clear influence on the media—shaping the direction of coverage, the selection of concepts and imagery, and the interpretative context of reported events—while also functioning, insofar as it is understood as a ‘speech act’, as a product of media influence (

Vultee, 2011, p. 78). This is particularly pertinent given that all information inherently contains an element of interpretation. Information cannot be wholly objective, as it is conveyed through specific concepts and categories of thought, with the implicit aim of influencing recipients—their attitudes, actions, and ways of thinking. Consequently, a widely held view in contemporary Russian security discourse is that information policy constitutes a critical component of state security policy (

Shamakhov & Kovalev, 2020, p. 103).

The role of the media in shaping social phenomena, including the promotion of desirable attitudes, judgements, behaviours, and values among audiences, is therefore integral to state security policy. According to Krebs, security policy encompasses the entirety of measures undertaken to reduce a state’s vulnerability to attack or other forms of external intervention, thereby reinforcing the public’s sense of security (

Krebs, 2018, p. 263). Given that media coverage significantly influences public sentiment, it holds considerable relevance in security policy. One particularly salient aspect of media influence is its role in shaping both individual and collective identity. This is manifested in the identification with a particular social, ethnic, or religious group, in the alignment of personal interests with those of the state, or in the voluntary subordination of individual interests to those of the state, which are perceived as superior. At the same time, identity formation through media narratives can foster a sense of separation, alienation, or even hostility towards other social, ethnic, or religious groups. Given this link between media influence and identity formation, the potential for using the media to shape the attitudes and beliefs desired by political elites constitutes a significant dimension of security policy. As Peter J. Katzenstein (

Katzenstein, 1996, pp. 18–19) observes, ‘

Definitions of identity that distinguish between self and other imply definitions of threat and interest that have strong effects on national security policies. […] For most of the major states, identity has become a subject of considerable political controversy’.

The extent of state influence over media narratives varies and is largely contingent on the degree of media autonomy, as well as the extent to which freedom of expression and the right to information are protected within a given political and legal framework. Consequently, the role of the media in shaping security policies differs across political and legal contexts. In Russia, however, the media play a particularly significant role in state-directed security policymaking. Contemporary Russian political discourse is dominated by narratives centred on national security, encompassing various aspects of both foreign and domestic policy (

Kulikova, 2017, p. 119). Moreover, Russian state-controlled media coverage exhibits a pronounced identity-driven character. A remarkably broad spectrum of media content—including issues related to culture, history, ideology, and values—is framed through a security lens. Given this context, it is essential to examine the key phenomena shaping the contemporary Russian discourse on information policy within the broader framework of state security policy, alongside its social and political dimensions.

4.4. Information Policy in Russian Strategic Documents Before 2022

Russian information policy, including measures defining the tasks and limitations of media coverage, has taken on an increasingly confrontational character in recent years. This is evident in the fundamental differences between two key strategic documents on information security—one from 2000 and the other from 2016.

Russia’s first Doctrine on Information Security (

Doktrina informatsionnoy bezopasnosti, 2000), signed by President Putin on 9 September 2000, was drafted in response to the evolving information sphere and the emerging threats to state security. While it acknowledged information-related threats to Russia, its primary focus was on securing the rights and freedoms of Russian citizens regarding access to information. Notably, this doctrine contained no ideological elements, such as references to historical politics or worldview issues, nor did it advocate for restrictions on information access. A similar approach is evident in another strategic document—the Strategy for the Development of the Information Technology Sector in the Russian Federation for 2014–2020, with an Outlook to 2025, approved on 1 November 2013 (

Pravitel’stvo Rossiyskoy Federatsii, 2013).

By contrast, the Doctrine of Information Security of the Russian Federation (

Doktrina informatsionnoy bezopasnosti, 2016), approved by presidential decree on 5 December 2016, adopts a markedly different stance. This document places a strong emphasis on threats posed by the hostile actions of foreign states, incorporates ideological concerns into state policy, and commits to increasing state control over media content (

Gritsenko, 2017, pp. 81–82). The context in which this second doctrine was formulated—following Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the pronounced anti-Western shift in its foreign policy—explains its confrontational nature (

Shamakhov & Kovalev, 2020, p. 126). The impact of geopolitical changes on Russia’s approach to information security was already evident in the Order of the Federation Council of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation on the Development of Information Technology and Support Measures for the National IT Sector, issued on 20 April 2016 (

Sovet Federatsii, 2016). This order recommended that the Russian government develop measures to enhance information security in response to the changing geopolitical situation and the imposition of Western sanctions on Russia.

The 2016 Doctrine assigns a heightened strategic role to information security, particularly in the sphere of media broadcasting, as an essential component of national security. Considerable attention is devoted to perceived threats from foreign states acting against Russia. The document warns of the ‘growing risk that information technologies will be used to infringe on the sovereignty, territorial integrity, or political and social stability of the Russian Federation’ (sec. 16). It also highlights concerns that foreign states, leveraging their technological advantage, may seek to dominate the global information space (sec. 19). The doctrine recognises information pressure from external actors as a key threat to Russian security and places strong emphasis on safeguarding Russia’s territorial integrity, a concern that is mentioned five times throughout the document (secs. 2d, 15, 16, 22, 23a). This emphasis is directly linked to the annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol in 2014, as any media narrative that challenges the legitimacy of this annexation could be deemed extremist and a threat to state security.

Notably, the measures outlined in the doctrine to ensure information security include objectives of an ideological and identity-based nature. Among the stated goals of Russia’s military policy is the ‘counteraction of information and psychological operations aimed at undermining historical foundations and patriotic traditions related to the defence of the homeland’ (sec. 21e). Furthermore, state authorities declare a priority to combat ‘the use of information technologies to promote extremist ideology, spread xenophobia, and propagate ideas of national exceptionalism with the aim of undermining sovereignty, political and social stability, forcibly altering the constitutional order, and violating the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation’ (sec. 33e). Additionally, the state is tasked with ‘neutralising information influences aimed at eroding Russia’s traditional moral and spiritual values’ (sec. 33j). The doctrine asserts that protecting sovereignty in the information space is a key national interest in the regulation of information dissemination (sec. 29a). Notably, it identifies the ‘development of a national system for managing Russia’s internet segment’ as a distinct strategic objective (sec. 29e). The 2016 Doctrine also explicitly designates the mass media as a key component of the information security system (sec. 33). This means that media owners and journalists in Russia are formally co-opted into the implementation of state security policy objectives in the information sphere. This has significant implications for the permissible scope of media content disseminated to Russian audiences.

A document of a similar nature, reflecting contemporary Russian information security policy, is the Strategy for the Development of the Information Society in the Russian Federation 2017–2030, signed by President Putin on 9 May 2017 (

Strategiya razvitiya informatsionnogo obshchestva v Rossiyskoy Federatsii na 2017–2030 gody, 2017). This strategy also incorporates ideological objectives, including ‘

the prioritisation of traditional Russian spiritual and moral values and adherence to behavioural norms based on these values in the use of information and communication technologies’ (sec. 3v). The document expresses scepticism towards the internet as a source of independent information, describing its content as superficial and warning that it can be exploited to impose externally dictated norms of behaviour. It also highlights the potential for states and organisations possessing advanced information technologies to use the internet for hostile purposes (sec. 16). Consequently, the document advocates for the state’s sovereign right to regulate the information space, including internet governance (sec. 17), and calls for the enhancement of legal mechanisms to regulate the activities of mass media (sec. 26r). Additionally, it emphasises the need for state authorities to support traditional media channels—such as radio, television, print media, and libraries—(sec. 26u), as these are more easily controlled.

Overall, contemporary Russian strategic documents relating to information policy and security clearly link this domain to broader security policy objectives. More recent documents, particularly those drafted after the onset of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, signal an intention to expand state control over the flow of information, particularly targeting channels that remain independent of government influence. Furthermore, these documents indicate that the state expects media outlets to align their messaging with official security policy, including ideological and worldview positions that are considered integral to Russian national identity and the state’s political structure. As Shamakov and Kovalev observe (

Shamakhov & Kovalev, 2020, p. 129), in the context of Russia’s confrontation with the West, recent strategic documents reflect a growing conviction that an integrated national information and communication space should be established. This space is expected to prioritise the national security of the Russian Federation and serve as a vehicle for defending its strategic interests.

5. Ideological Creation of the Image of Central and Eastern European Countries (Case Studies)

The context outlined above—comprising academic debate and Russian strategic documents—provides a framework for understanding the language of media narratives directed at Russian audiences concerning Central and Eastern European states in the post-2014 period. The key elements of this discourse were already present, having been employed to describe political events perceived in Russia as manifestations of Western aggression and encroachments on its sphere of influence in Europe. These include NATO’s intervention in Yugoslavia in 1999, the expansion of NATO to include former Warsaw Pact countries, and the enlargement of the European Union. However, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has intensified the tone of media narratives, reinforcing the portrayal of the West as Russia’s existential enemy and the necessity of supporting the state authorities in defending Russian political interests—even at the cost of economic hardship. It is within this interpretative framework that the content and objectives of Russian media coverage of former communist bloc countries, now integrated into Western military and political structures, should be understood.

A significant element of this discourse is its confrontational nature. In Russian media narratives, the cooperation of Central and Eastern European countries with the West—whether political, economic, or military—is equated with a loss of sovereignty and national identity. Identity plays a crucial role in these narratives, particularly through the emphasis on traditional values as fundamental to European civilisation’s survival—values that Russia now claims to defend. In this context, historical policy is especially significant. The actions of Central and Eastern European governments are often depicted as attempts to reinterpret history, particularly with regard to the Second World War, by diminishing the Soviet Union’s role in the victory over Nazism and in the liberation of these countries from occupation.

It is important to recognise, however, that these messages are not intended for the citizens of Central and Eastern European countries but rather for Russian audiences. This distinction shapes not only the content of the media discourse but also its objectives. These objectives align with Russia’s broader security policy, which includes fostering an awareness of Russian cultural and social distinctiveness and consolidating Russian society around the state authorities.

To examine how Russian media narratives support the objectives of Russian security policy in the information sphere by constructing a politically and ideologically desirable image of Central and Eastern European states, three countries were selected for analysis. The results of the media content analysis presented below focus on Latvia, Poland, and Serbia. These countries, all part of the Central and Eastern European region defined in the introduction, exhibit distinct characteristics that influence both the primary areas of interest for Russian media and the direction in which their images are shaped in alignment with Russian security policy objectives.

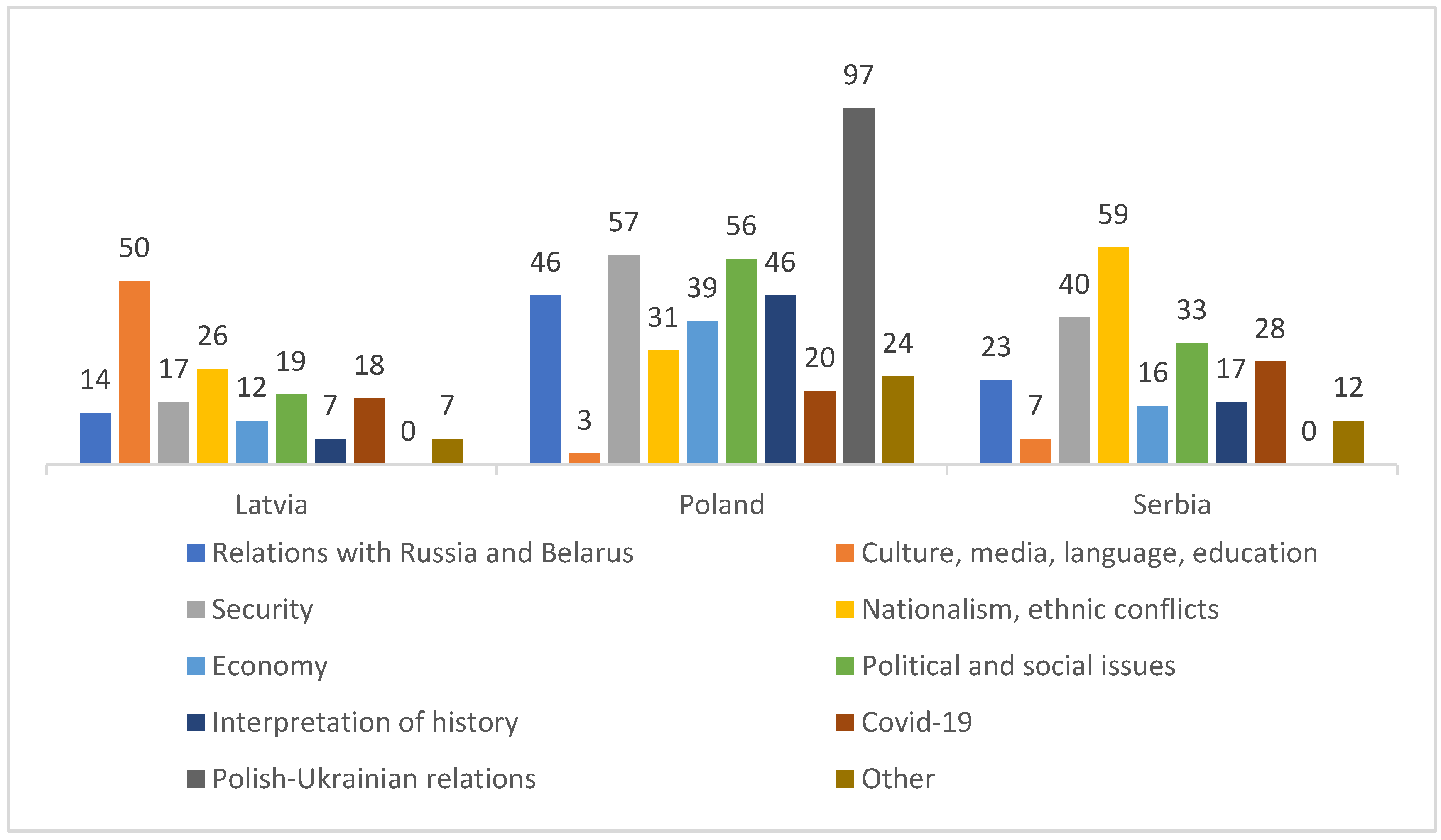

Figure 1 shows a general distribution of the topics covered by the surveyed media content for the selected three countries.

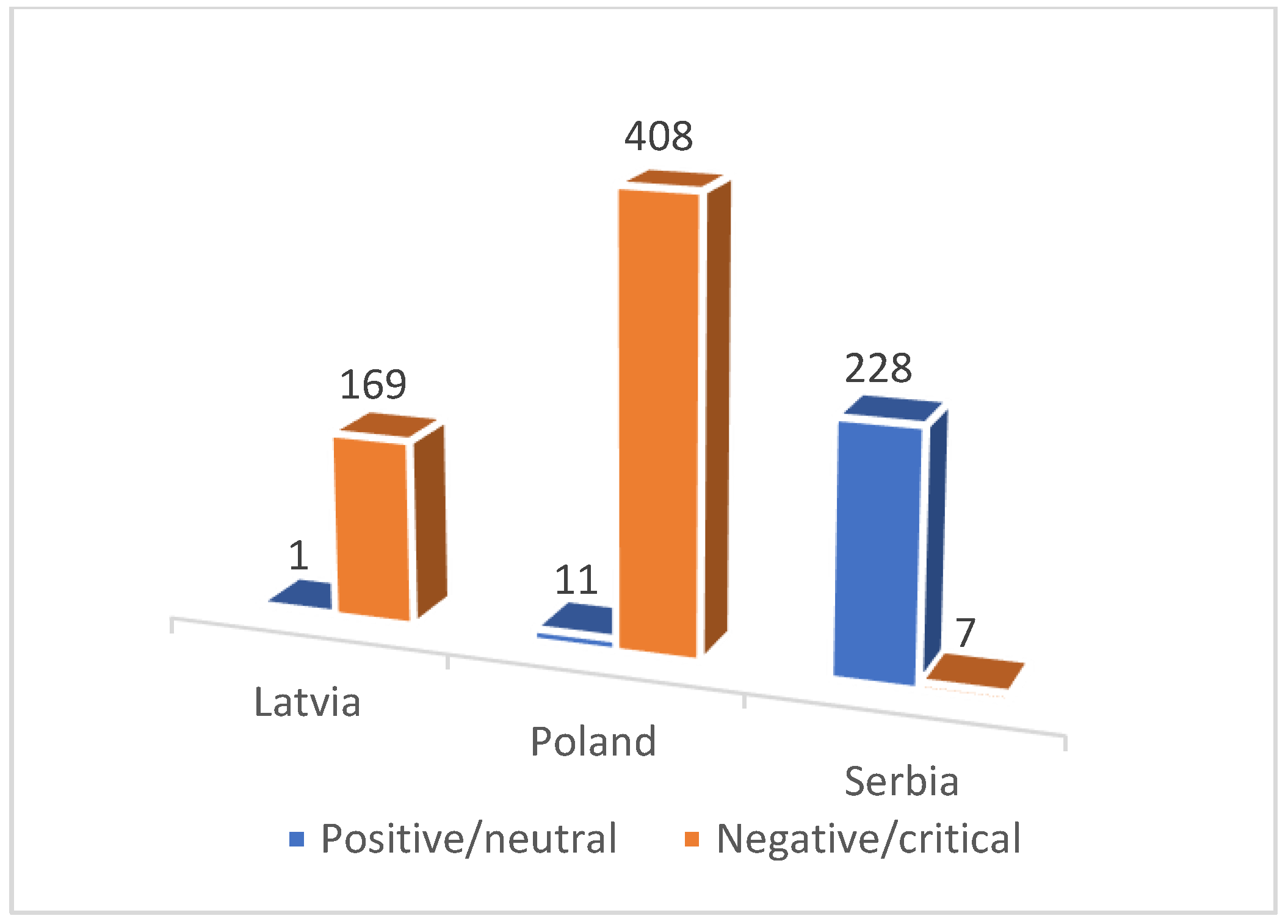

Latvia and Poland are members of both the European Union and NATO, whereas Serbia, despite aspiring to join the European Union, does not seek membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. Latvia, as one of the Baltic states alongside Lithuania and Estonia, was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940 following the implementation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Due to Soviet-era policies after the Second World War, Latvia today has a substantial Russian-speaking population, and ethnic and linguistic issues remain a key source of tension between Latvia and Russia. Poland, in turn, is frequently portrayed in Russian political and media discourse as an inherently anti-Russian state. Anti-Polish sentiment in Russian public debate has intensified since Poland provided support to Georgia (in 2008) and Ukraine (in 2014) in the face of Russian aggression. Serbia, by contrast, is considered a political ally of Russia. Serbian society is perceived as culturally close to Russian society, partly due to shared religious traditions. Given these differences, Russian media coverage—while implementing the broader elements of Russian security policy in the information sphere—can be expected to construct significantly different narratives for each of these countries. The media materials surveyed reveal the RIA-Novosti’s ideological commitment. The coverage of Latvia and Poland is mostly negative, and Serbia mostly positive, as shown in

Figure 2.

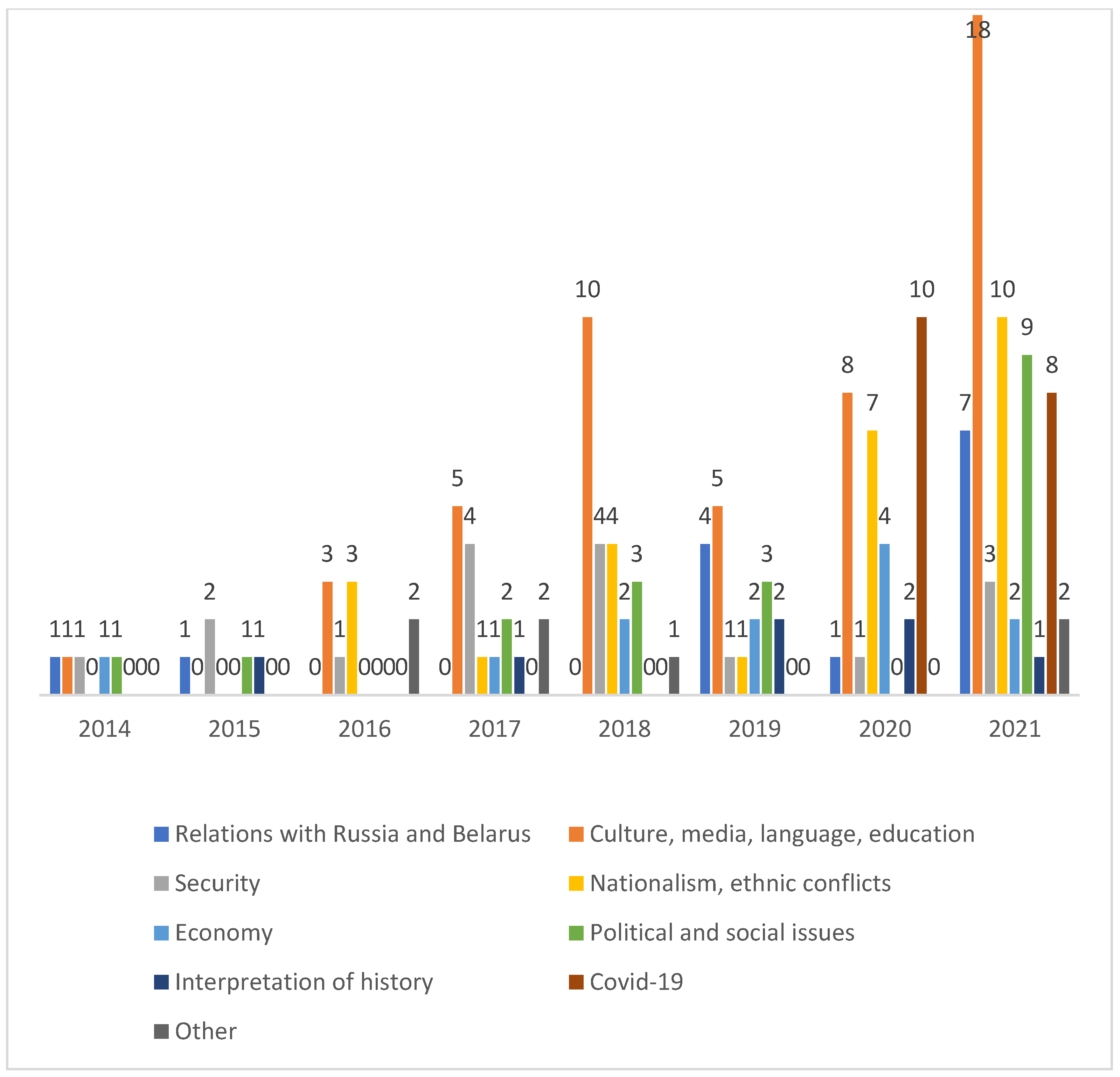

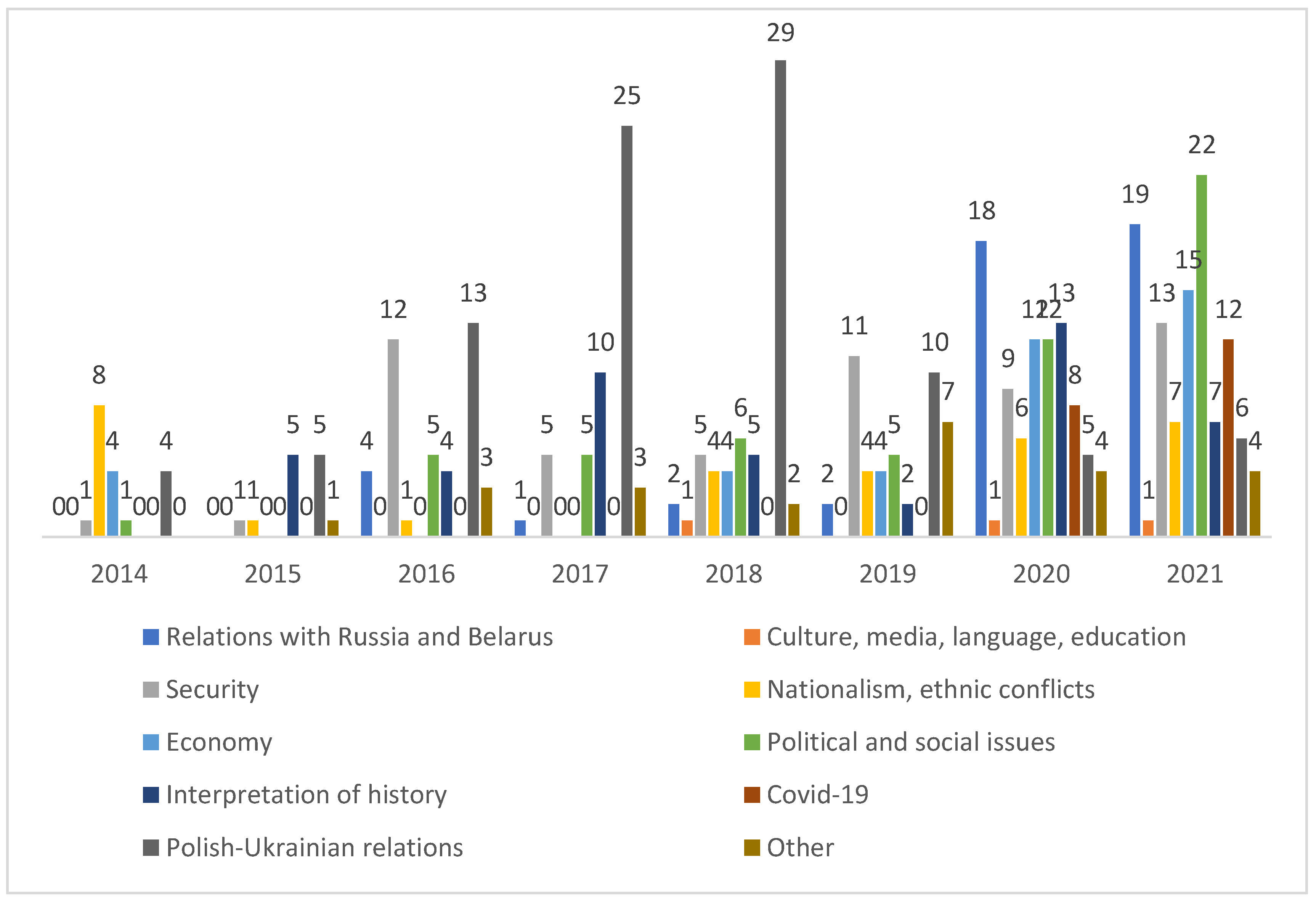

5.2. Poland

As in the case of Latvia, the analysed materials from Russian media concerning Poland are overwhelmingly critical. Poland’s foreign and domestic policies are portrayed in a highly negative light. The country is depicted as being in political and economic turmoil and as internationally isolated. Russian media narratives emphasise Poland’s subordinate role within the European Union and the high financial burden associated with its military alliance with the United States. Historical narratives also play a significant role in this coverage. Russian media portray Poland negatively in relation to both the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 and the Second World War. The only positive references to Poland in Russian media coverage concern Polish opposition to the dismantling of ‘monuments of gratitude’ dedicated to the Soviet army. The general distribution of RIA-Novosti’s media coverage in relation to Poland is shown in

Figure 4.

Poland is consistently depicted as a politically, militarily, and economically weak state with imperial ambitions. A recurring theme in Russian media coverage is Polish-Ukrainian relations, although a noticeable shift in emphasis has occurred over time. Between 2014 and 2017, media narratives sought to highlight tensions in Polish-Ukrainian relations—for instance, by reporting that former Polish anti-terrorist unit soldiers had fought alongside Ukrainian ‘punishers’ in the Donbas, while simultaneously emphasising the anti-Polish nature of Ukrainian nationalism. However, in later years, coverage has focused predominantly on negative depictions of Ukrainians in Poland, including reports of criminality among Ukrainian migrants and instances of xenophobic behaviour towards them. More recent media narratives emphasise joint Polish-Ukrainian actions against Russia, particularly declarations of coordinated efforts to restore Ukrainian territories annexed by Russia.

A constant element of Russian media discourse is the accusation of Russophobia in Poland, which is often framed within historical narratives. Notably, the frequency of media reports on historical issues increased following President Putin’s widely publicised statement accusing Poland of co-responsibility for the outbreak of the Second World War (

Vladimir Putin raspalyalsya vse Pol’she i Pol’she, 2019). The principal manifestations of Polish Russophobia, according to Russian media, include the dismantling of monuments dedicated to Soviet soldiers and allegations that Poland falsely accuses the Soviet Union of having jointly initiated the Second World War alongside Nazi Germany in 1939. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Polish-Bolshevik War, significant media attention was devoted to alleged war crimes committed by the Polish army against Bolshevik soldiers and the civilian populations of Belarus and Ukraine. At the same time, the Bolshevik invasion of Poland is assessed positively. The rehabilitation of the so-called cursed soldiers—members of the anti-communist Polish underground who continued to resist the Soviet-imposed communist regime after the Second World War—is also subject to criticism. These soldiers are at times referred to in Russian media as ‘bandits’ and ‘executioners’ (

palachi).

More recent Russian media coverage has focused on social issues in Poland. Between 2020 and 2022, substantial attention was given to reports suggesting that Poland was struggling to manage the coronavirus pandemic and that the state of its healthcare system was dire. Reports also frequently covered protests by LGBTQ+ communities. However, these narratives should be understood in the broader Russian context. The same media outlets present Russia as having successfully managed the pandemic while simultaneously depicting it as a country upholding traditional values in contrast to the West, which is portrayed as promoting expanded rights for sexual minorities.

Within the broader framework of anti-Western rhetoric, two additional aspects of Russian media coverage of Poland are noteworthy. Firstly, Poland is either depicted as being isolated within the European Union or as occupying a subordinate position, similar to other former Eastern Bloc states. In this context, Russian propaganda between 2017 and 2018 frequently exploited the alleged double standards in food quality, suggesting that products of the same brands were of inferior quality in Central and Eastern Europe compared to those sold in Western Europe. Secondly, Russian media highlight the financial burden associated with the deployment of US troops in Poland, stressing the significant costs Poland will incur as a result.

Finally, Russian media coverage consistently emphasises Poland’s economic and military weakness. In economic terms, Poland is portrayed as being dependent on Russian energy resources, particularly coal, oil, and gas, while efforts to diversify energy supplies and reduce reliance on Russia are dismissed as unrealistic. In the military sphere, Russian propaganda frequently highlights the alleged weakness and technological obsolescence of the Polish armed forces, asserting that they would be incapable of defending Poland in the event of a military conflict with Russia and Belarus.

5.3. Serbia

The media portrayal of Serbia contrasts sharply with the narratives presented in Russian media coverage of Latvia and Poland. While Russian media employ the same overarching themes that define contemporary Russian security policy discourse, these themes are framed in a distinctly different manner. Cooperation with the West is depicted as detrimental to Serbia’s national interests, whereas an alliance with Russia is portrayed as essential for Serbia’s survival and development. The scale and significance of Russian-Serbian economic and military cooperation are emphasised. Historical and identity politics also play a crucial role. As in the cases of Latvia and Poland, Russian media devote substantial attention to the coronavirus pandemic and its consequences. However, while coverage of Latvia and Poland is overwhelmingly negative, media narratives about Serbia are largely positive, with criticism appearing only in the context of Serbia’s aspirations for European Union membership.

The general distribution of RIA-Novosti’s media coverage in relation to Serbia is shown in

Figure 5.

A central claim running through much of Russian media coverage of Serbia is that Russia is Serbia’s most important ally and friend on the international stage. This alliance is said to manifest not only in symbolic gestures but also in substantive economic and military cooperation. In economic terms, Russia is depicted as a key partner in Serbian infrastructure projects and as the guarantor of Serbia’s energy security through gas supplies. In the military sphere, Russia is presented as the primary supplier of weaponry to the Serbian armed forces. The closeness between Russia and Serbia is also framed as having a cultural dimension. Russian media highlight the unity of the Russian and Serbian Orthodox Churches, particularly in relation to the division within the Orthodox Church in Ukraine, where the Serbian Church is reported to support the Russian Church.

Against this backdrop, Russian media narratives are explicitly critical of Serbia’s cooperation with the European Union. The EU is portrayed as exerting undue pressure on Serbia to recognise Kosovo’s independence, while simultaneously attempting to impose cultural and identity-based changes, such as the recognition of LGBTQ+ rights. According to Russian media, the majority of Serbs oppose integration with the West and favour a deepening of relations with Russia. In this context, Serbia’s refusal to recognise Russia’s annexation of Crimea is framed as a consequence of Western pressure. Additionally, it is argued that Serbia’s recognition of Crimea would necessitate its recognition of Kosovo’s independence, thereby reinforcing Serbia’s position against such a move.

Identity and historical narratives constitute a significant part of Russian media discourse on Serbia. Russian media emphasise that Serbia rejects any attempt to downplay the Soviet Union’s role in the defeat of Nazism during the Second World War and continues to acknowledge the contributions of the Red Army in the liberation of Yugoslavia. More recent historical events, such as NATO’s 1999 air strikes against Yugoslavia, also feature prominently in Russian media. These events are presented both as justification for Serbia’s right to seek reparations and, more explicitly, as an argument against Serbia’s potential membership in NATO.

Perhaps the most notable aspect of Russian media coverage in the context of Russian security policy—particularly in comparison with the portrayals of Latvia and Poland—is the depiction of Serbia’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. While Russian media highlight the inefficiency of the healthcare systems and severe social problems in Latvia and Poland, their coverage of Serbia’s pandemic response is distinctly positive. Reports describe Serbia’s handling of the pandemic without resorting to dramatic imagery. More significantly, Russian media consistently stress Russia’s support for Serbia by supplying the Sputnik V vaccine and exploring the possibility of joint vaccine production. Russian media reports also note that Serbia is using both the Sputnik V vaccine and the US-German Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. However, these reports emphasise that Western vaccine manufacturers have failed to meet their declared supply commitments. More importantly, Russian media assert that the Sputnik V vaccine is safer than its Western counterpart, alleging that most reported side effects occur after administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

6. Discussion

The cited Russian strategic documents, along with the content of contemporary Russian academic debate on media discourse, indicate that, particularly since 2014, there has been an increasing emphasis on the media’s role in the implementation of state security policy. This emphasis also serves to justify the growing state control over the media and efforts to restrict independent channels of information. Since media coverage is framed as a security issue, it is deemed justifiable to apply security-related measures to it (

Peoples & Vaughan-Williams, 2015, pp. 93–94). Even if some scholars (

Hough, 2018, p. 19) regard this approach as an unjustified expansion of the concept of security, there is no doubt that it has been effectively implemented in the Russian context.

By juxtaposing elements of the Russian academic debate and recent strategic documents with Russian media coverage of selected Central and Eastern European states, it is possible to discern how the Russian authorities conceptualise the media’s role in state security policy. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia experienced a profound identity crisis, as noted by Holger Mölder (

Mölder, 2016, p. 99). Addressing this crisis has been among the priorities of state security policy, as articulated by President Vladimir Putin and enshrined in strategic documents issued during his presidency. More recent documents are notably confrontational in tone. Likewise, an analysis of media coverage reveals that Central and Eastern European states pursuing policies that conflict with Russian interests are subjected to near-total criticism in Russian media. Many scholars argue (

Averre, 2018, p. 154) that both Russian political discourse and media narratives increasingly exhibit a revival of imperialist rhetoric. This is evident, on the one hand, in the devaluation of values, principles, and socio-political models that are not traditionally associated with Russia. Western democratic values are dismissed as detrimental to Russian interests and security. On the other hand, this discourse is reflected in the denial of political independence to states that were formerly under Soviet control. This tendency is most pronounced in relation to Ukraine, where both Russian political elites and media narratives frequently express contempt for Ukraine’s legitimacy and sustainability as a state (

Alexseev & Hale, 2016, p. 196). To a certain extent, this perspective also extends to other Central and Eastern European countries. Any assertion of independence from Russian influence is invariably interpreted as subjugation to another external power—primarily the United States. At the same time, Russian media coverage consistently portrays alignment with Western political and cultural influence as detrimental to the identity and traditions of the region’s states.

In this context, three key areas can be identified in which the media’s portrayal of Central and Eastern European states aligns with the objectives of contemporary Russian security policy.

(1) State-Centric Information Policy and National Security: The conceptualisation of information policy within Russian academic discourse and strategic documents is strongly state-centric. The state is regarded as the principal guarantor of multidimensional security, with national security closely linked to the protection of citizens’ rights and interests (

Kulikova, 2017, p. 119). Patriotism has become a central tenet of Russian information policy (

Shamakhov & Kovalev, 2020, p. 156) and, in Putin’s view, constitutes a fundamental component of Russian state ideology (

U nas net, 2016). Given the centrality of the state in all aspects of security (

Dobrenkov & Agapov, 2011, pp. 118–119), any perceived weakness in the state is considered a direct threat to national security. Consequently, the state is deemed responsible for regulating the information accessible to its citizens and shaping their worldview. Media narratives that diverge from official state policy are subject to severe criticism in academic discourse and, as in the work of Shamakhov and Kovalev (

Shamakhov & Kovalev, 2020, p. 108) are sometimes framed as betrayals of national interests. Opposition journalists are frequently portrayed as traitors or foreign agents. Shamakhov and Kovalev further argue (

Shamakhov & Kovalev, 2020, p. 107) that ‘

In contemporary Russia, only state information policy, pursuing and protecting the interests of power, is relevant. There is no question of any real opposition policy as such, or of an opposition information policy in particular, under the current conditions. Therefore, any non-state information policy can be understood, and is generally understood now, as something hostile to the existing state, as evidenced by the recognition of many media and social organisations as foreign agents’. An analysis of Russian media coverage clearly indicates that Central and Eastern European states are never discussed in isolation but are always positioned within the broader context of their relations with Russia. The nature of these relations serves as the foundation for how Russian media assess various aspects of social, economic, and cultural life, even those seemingly unrelated to international politics. Consequently, states perceived as adversaries of Russia—such as Latvia and Poland—are consistently portrayed in a negative light across all areas of media coverage.

(2) Ideological and Worldview Commitment in Media Narratives: In line with Russian security policy objectives, media narratives are expected to reflect a worldview and ideological stance consistent with the authorities’ directives. A key aspect of this approach is the identity dimension of media messaging. State-controlled media play an active role in promoting identity-related objectives, leading, as Katri Pynnöniemi observes (

Pynnöniemi, 2016, p. 72), to a continuation of Soviet-era propaganda techniques, which were characterised by indoctrination and the ritualisation of political language. The language of media propaganda employs specific terms that are both value-laden and emotionally charged (

Pakhomenko & Tryma, 2016). This is particularly evident in Russian media coverage of the conflict in Ukraine, where terminology is deliberately chosen to shape public perceptions. For instance, Ukrainian soldiers fighting against pro-Russian forces are referred to as ‘punishers’ (

karateli), while pro-democratic changes in Ukraine are labelled as fascist. The post-2014 Ukrainian government is frequently described as a ‘junta’, implying illegitimacy (

Kyryliuk, 2021, pp. 1426–1427). A similar ideological vocabulary is evident in media portrayals of Central and Eastern European states, where hyperbolic and emotive language is used extensively. One of the most prominent terms employed in both media and political discourse is Russophobia, which serves as a broad and flexible label to denote a hostile attitude towards Russia (

Pynnöniemi, 2016, p. 77).

(3) The Role of Historical Narratives in Security Policy: Historical narratives play a particularly significant role in Russian media discourse and are closely aligned with the objectives of state security policy. The reinterpretation of history—or historical policy—serves as a key mechanism for shaping public perceptions and fostering a negative image of the West, including Central and Eastern European states. Media narratives concerning historical events are highly ideologically and emotionally charged, particularly those related to 20th-century history and, most notably, the Second World War (

Kyryliuk, 2021, pp. 1434–1435). Media accounts support the argument—widely advanced by contemporary Russian scholars of security studies—that securing an interpretation of history that aligns with the interests of the Russian authorities is a crucial component of the information warfare against the West (

Voronova & Trushin, 2019, p. 93).

7. Conclusions

The juxtaposition of the key themes of Russian security policy with the narratives disseminated by Russian federal media regarding selected Central and Eastern European states and societies leads to the following conclusions.

Firstly, Russian federal media coverage of Central and Eastern European states and societies is generally value-laden, with few statements of a neutral or purely informative nature. Consequently, states that are perceived as political adversaries of Russia—such as Latvia and Poland, as examined in this article—are consistently portrayed in a negative light. By contrast, states regarded as allies of Russia—such as Serbia—are depicted in almost exclusively positive terms. Notably, this valorisation in media coverage is not confined to issues related to these countries’ relations with Russia. Even discussions of ostensibly unrelated topics, such as social, economic, or cultural matters, are shaped by evaluative language, either positive or negative. This trend was also evident in media reporting on the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 and 2021. While coverage of Latvia and Poland emphasised the challenges of managing the pandemic, portraying their healthcare systems as ineffective, Serbia was depicted far more favourably, with particular emphasis on Russian-Serbian cooperation in combating the virus. However, the most emotionally and ideologically charged language in Russian media coverage pertains to historical issues.

Secondly, an analysis of Russian federal media’s portrayal of selected Central and Eastern European states after 2014 indicates that the primary criterion for evaluating social and political developments in these countries is their alignment or misalignment with Russian political interests. Russian federal media do not, as a rule, engage in critical debate over state policy towards these countries or question official interpretations of historical events. Instead, the statements of government representatives—particularly those of President Putin—serve as a foundation for journalistic discourse and as the principal frame of reference for assessing political, social, and cultural phenomena in Central and Eastern Europe.

Thirdly, an examination of Russian media coverage of Central and Eastern European states in the context of Russia’s recent security policy documents reveals a strong correlation between content and objectives. In terms of content, the media narrative incorporates strong identity-based, ideological, and axiological elements. These narratives seek to depict Central and Eastern European states that have integrated into Western political and military structures as adversaries of Russia. Moreover, Russian media emphasise that membership in these structures does not deliver the anticipated benefits to these states. On the contrary, they are portrayed as suffering economic decline and being subjected to cultural and moral pressures. By contrast, in the case of Serbia, Russian media highlight shared political and economic interests, cultural proximity, and the benefits of cooperation with Russia for Serbian society and the state.

From an objective standpoint, it is evident that the image of Central and Eastern European states constructed for Russian-speaking audiences by federal media corresponds closely with the strongly confrontational rhetoric found in Russian strategic security policy documents and in official government statements. Media narratives reinforce the argument—prevalent in these documents—that since 2014, Russia has been the victim of multifaceted aggression from the West. The media further support the notion that the only viable path for Russia to maintain its rightful international status and cultural identity is through the confrontational policies pursued by its leadership.

It can therefore be concluded that there is a strong link between the objectives of Russian security policy in the realm of information, as outlined in state documents, and the narratives disseminated by federal media. These media outlets, in line with governmental expectations, function as instruments for shaping public attitudes, worldviews, and beliefs in accordance with state directives. Consequently, in the federal media, content that diverges from or contradicts the objectives of Russian security policy, as analysed here, is virtually absent.

This leads to the conclusion that as the crisis in relations with the West deepens, the Russian authorities are likely to intensify efforts to restrict or block Russian citizens’ access to independent sources of information, particularly via the Internet. These independent sources will be increasingly framed as representing the interests of foreign states and organisations, and thus as posing a threat to national security. At the same time, in line with the indications already present in Russian strategic documents, one can expect further state support for state media as a means of consolidating control over public discourse.