Photojournalist Framing in the Ecological Crisis: The DANA Flood Coverage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fostering Civic Engagement Through Visual Information

3. Effective Visual Communication on Climate Change

4. Photojournalist Framing in Ecological Emergencies

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Objectives and Research Questions

- RQ1.

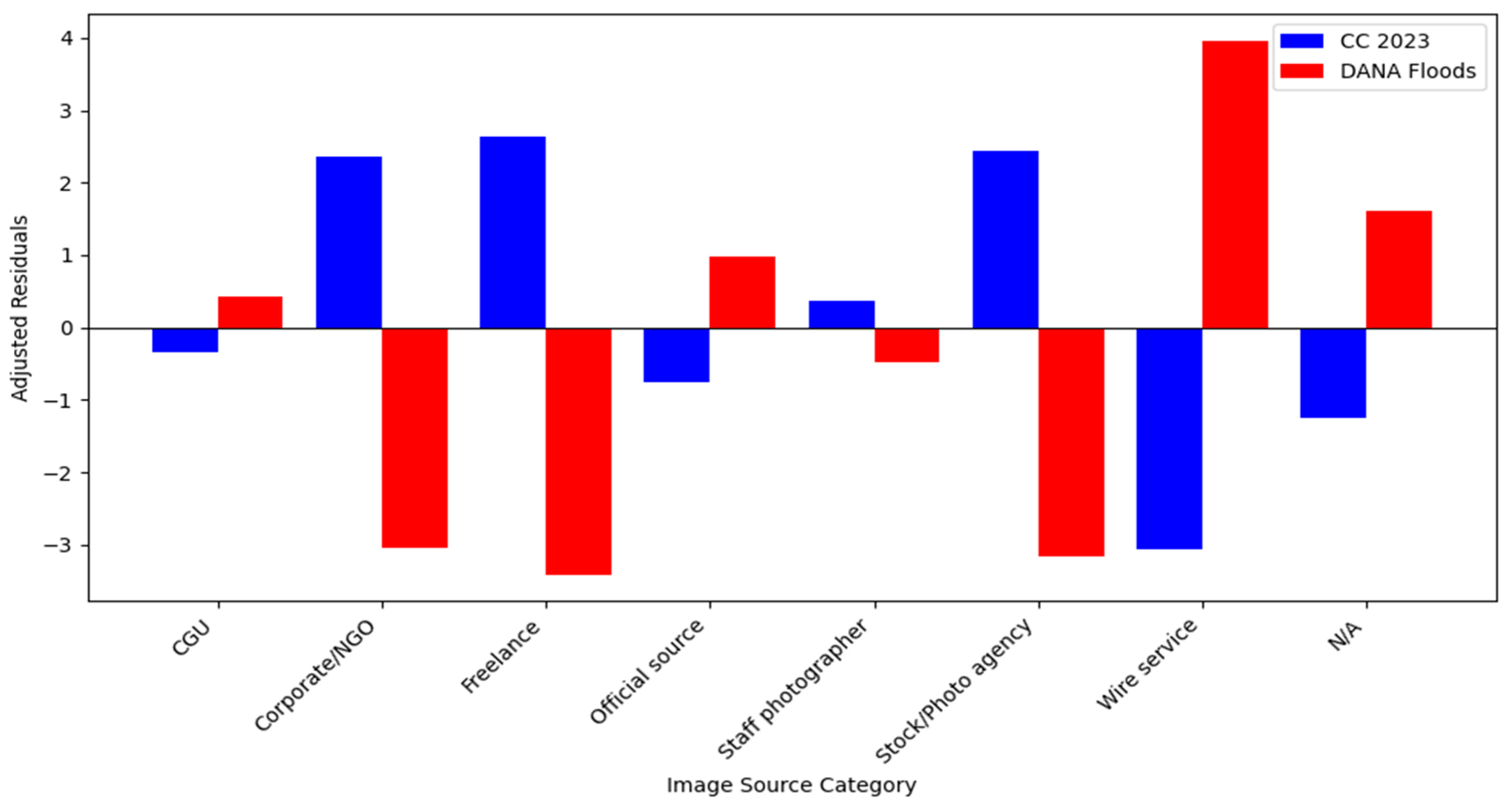

- Do newspapers rely more on wire service and stock photos or on original images taken by staff photographers and regular contributors?

- RQ2.

- What ethical issues, such as lack of attribution or misattribution, arise in visual coverage, and how do they relate to the use of stock images, UGC, and professional photography?

- RQ3.

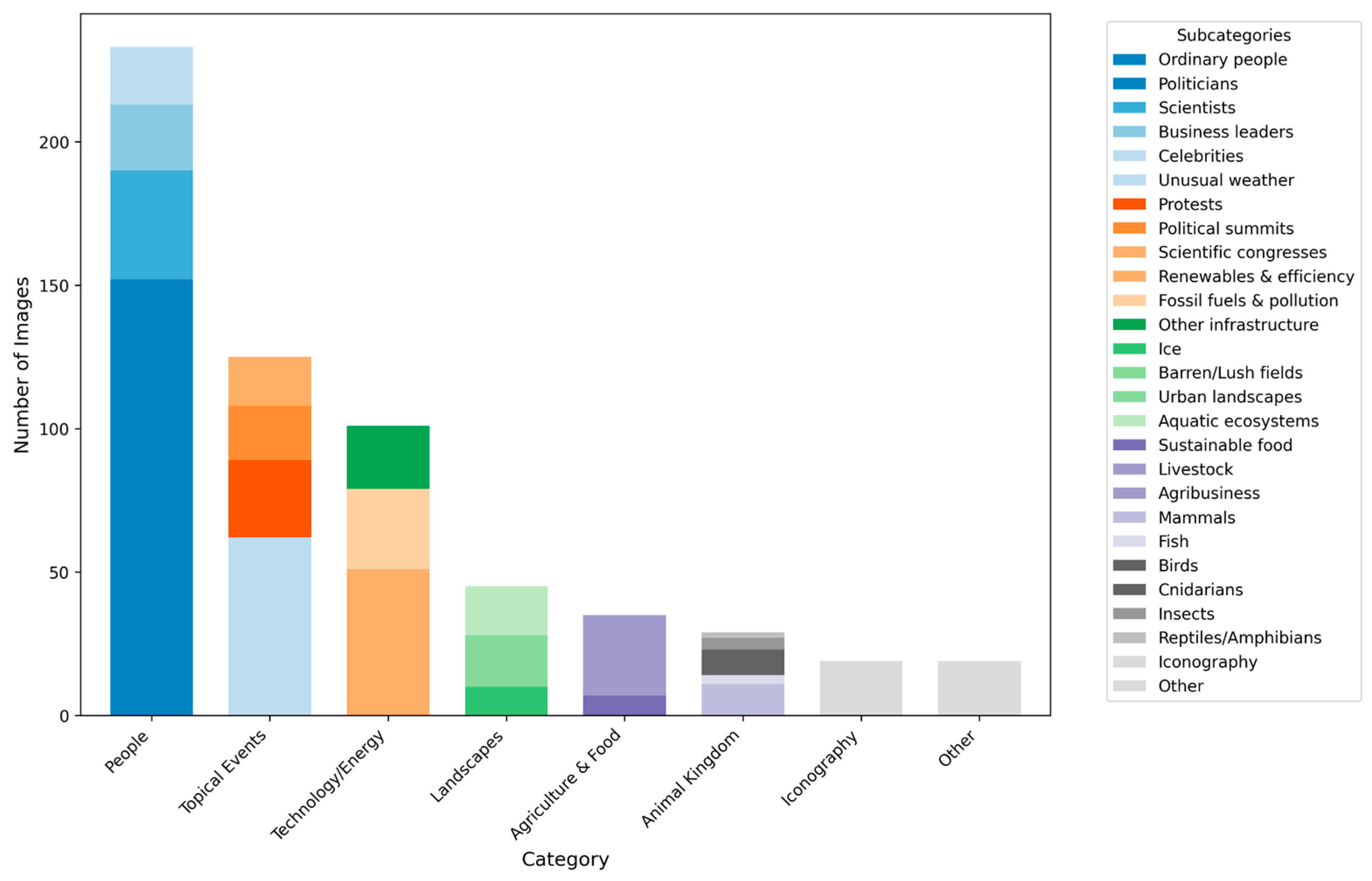

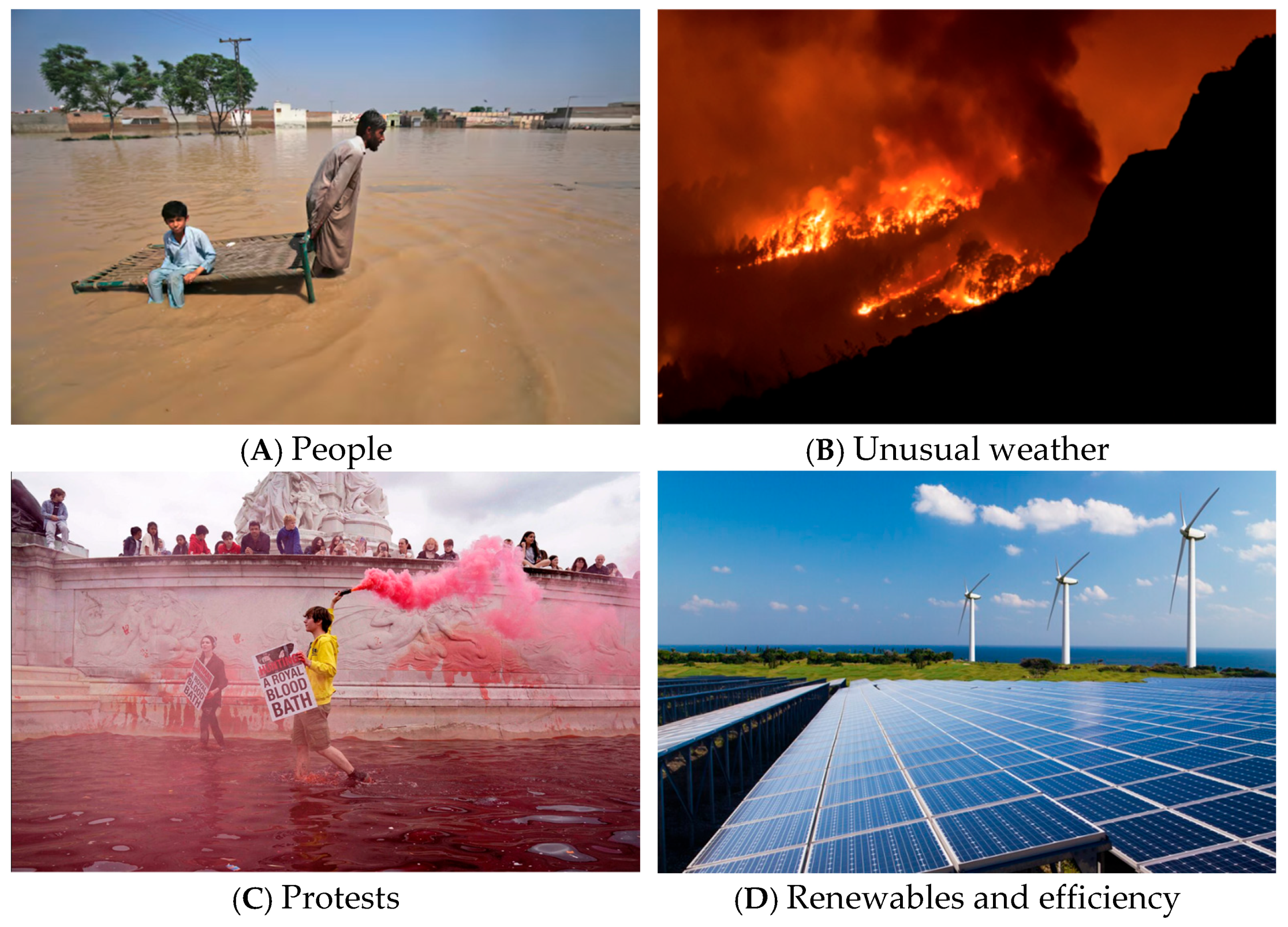

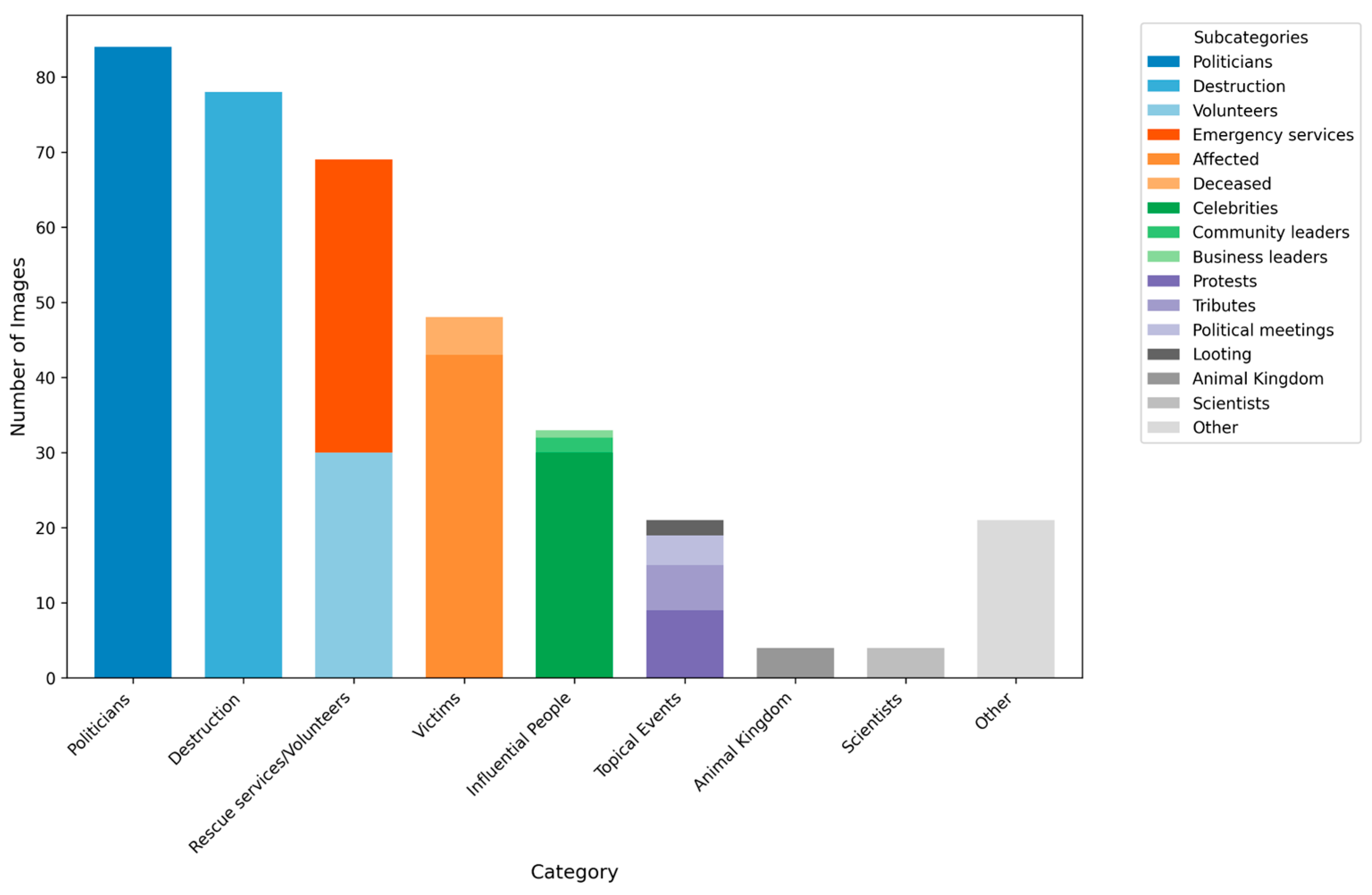

- What themes dominate the visual dimension of CC and DANA, and how do these images challenge or reinforce established visual patterns?

- RQ4.

- To what extent do the photographs in the selected articles reflect the problem, the solution, or both?

5.2. Sample and Design

5.3. Data Acquisition and Processing

5.3.1. Content Analysis and Denotative Meaning

- Media outlet: El País, El Mundo, La Vanguardia.

- Date: dd/mm/yyyy

- Image source: staff photographer; freelance, wire service; stock photo agency; official source—e.g., institutional communication services; corporate entities and ONGs—e.g., Iberdrola, Greenpeace; UCG; uncredited.

- Theme: topical events; agriculture and food; iconography; landscapes; people; animal kingdom; technology/energy; and others.

- Location: national, international.

- Attribution: complete—the distributor and the individual author are identified; partial—only the distributing source is identified; unattributed.

5.3.2. Framing Analysis and Connotative Meaning

6. Results

6.1. Content Analysis

6.2. Thematic Hierarchy

6.3. Visual Framing: Problems vs. Solutions

6.3.1. Problem- and Solution-Only Articles

6.3.2. Combined Framing: Problems and Solutions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Null Hypothesis | Alternative Hypothesis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| There is no difference in the distribution of image sources between CC 2023 and DANA floods | There is a significant difference in the distribution image sources between CC 2023 and DANA floods | |||

| Source type | CC 2023 | DANA Floods | ||

| Frequency Observed | Frequency Expected | Frequency Observed | Frequency Expected | |

| UGC | 30 | 31.89 | 21 | 19.11 |

| Corporate/ONG | 89 | 69.42 | 22 | 41.58 |

| Freelance | 59 | 41.90 | 8 | 25.10 |

| Official source | 23 | 26.89 | 20 | 16.11 |

| Staff photographer | 114 | 110.07 | 62 | 65.93 |

| Stock/Photo agency | 79 | 60.04 | 17 | 35.96 |

| Wire service | 191 | 238.27 | 190 | 142.73 |

| N/A | 21 | 27.52 | 23 | 16.48 |

| Total | 606 | 363 | ||

| CC 2023 | DANA Floods | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Attribution | Complete | 434 | 71.6 | 281 | 77.4 |

| Partial | 83 | 13.7 | 44 | 12.1 | |

| Misattributed | 7 | 1.2 | 4 | 1.1 | |

| Unattributed | 82 | 13.5 | 34 | 9.4 | |

| Total | 606 | 100 | 363 | 100 | |

| Attribution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete | Complete | Total | % Incomplete | ||

| Source type | Stock/Photo agency | 62 | 34 | 96 | 64.6 |

| Corporate/ONG | 38 | 73 | 111 | 34.2 | |

| UGC | 14 | 37 | 51 | 27.5 | |

| Official source | 9 | 34 | 43 | 20.9 | |

| Wire service | 67 | 314 | 381 | 17.6 | |

| Freelance | 6 | 61 | 67 | 9.0 | |

| Staff photographer | 14 | 162 | 176 | 8.0 | |

| Total | 210 | 715 | 925 1 | ||

| Frequency | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | People | 233 | 38.4 |

| Topical events | 125 | 20.6 | |

| Technology/energy | 101 | 16.7 | |

| Landscapes | 45 | 7.4 | |

| Agriculture and food | 35 | 5.8 | |

| Animal kingdom | 29 | 4.8 | |

| Iconography | 19 | 3.1 | |

| Other | 19 | 3.1 | |

| Total | 606 | 100 |

| Article Frame | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem-Only | Problem-Solution | Solution-Only | Neutral | Total | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Destruction | 71 | 19.5 | 7 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 21.5 |

| Politicians | 43 | 11.8 | 6 | 1.7 | 31 | 8.5 | 4 | 1.1 | 84 | 23.1 |

| Topical events | 12 | 3.3 | 8 | 2.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 5.8 |

| Influential people | 13 | 3.6 | 2 | 0.5 | 7 | 1.9 | 11 | 3.0 | 33 | 9.1 |

| Scientists | 3 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Other | 5 | 1.4 | 5 | 1.4 | 5 | 1.4 | 6 | 1.7 | 21 | 5.8 |

| Victims | 27 | 7.4 | 16 | 4.4 | 3 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.8 | 49 | 13.5 |

| Rescue services/volunteers | 6 | 1.6 | 46 | 12.7 | 17 | 4.7 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 19 |

| Animal kingdom | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Total | 182 | 50.1 | 92 | 25.3 | 65 | 17.9 | 24 | 6.6 | 363 | 100 |

References

- Aiello, G., Kennedy, H., Anderson, C. W., & Mørk Røstvik, C. (2022). ‘Generic visuals’ of COVID-19 in the news: Invoking banal belonging through symbolic reiteration. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(3–4), 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, N. B. (2015). Analysing communication processes in the disaster cycle: Theoretical complementarities and tensions. In R. Dahlberg, O. Rubin, & M. T. Vendelø (Eds.), Disaster research: Multidisciplinary and International perspectives (pp. 126–139). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Andén-Papadopoulos, K. (2014). Citizen camera-witnessing: Embodied political dissent in the age of ‘mediated mass self-communication’. New Media & Society, 16(5), 753–769. [Google Scholar]

- Anne DiFrancesco, D., & Young, N. (2011). Seeing climate change: The visual construction of global warming in Canadian national print media. Cultural Geographies, 18(4), 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardèvol, E., Martorell, S., & San-Cornelio, G. (2021). Myths in visual environmental activism narratives on Instagram. Comunicar, 68, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación. (2025). Marco general de los medios en españa 2024. Available online: https://www.aimc.es/a1mc-c0nt3nt/uploads/2025/02/Marco_General_Medios_2025.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Baberini, M., Coleman, C. L., Slovic, P., & Västfjäll, D. (2015). Examining the effects of photographic attributes on sympathy, emotions, and donation behavior. Visual Communication Quarterly, 22(2), 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, P. (2004). Content analysis of visual images. In T. Van Leeuwen, & C. Jewitt (Eds.), The handbook of visual analysis (pp. 10–34). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brusi, A., Alfaro, P., & González, M. (2008). Los riesgos geoló-gicos en los medios de comunicación: El tratamiento informativo de las catástrofes naturales como recurso didáctico. Enseñanza de las Ciencias de la Tierra, 16(2), 154–166. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/ECT/article/view/127772 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Buoncompagni, G. (2025). The Visual Sociography of Disaster Journalism: A Local Case Study. Journalism and Media, 6(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caple, H. (2013). Photojournalism: A social semiotic approach. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, D. A., Corner, A., Webster, R., & Markowitz, E. M. (2016). Climate visuals: A mixed methods investigation of public perceptions of climate images in three countries. Global Environmental Change, 41, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colegio Oficial Psicología Santa Cruz de Tenerife. (2021, September 19). IMPORTANTE: No compartas en redes sociales imágenes o vídeos de viviendas derrumbándose [...] Por favor, ¡difunde este mensaje! #LaPalma #VolcandeLaPalma [Tweet]. Twitter (X). Available online: https://x.com/copsctenerife/status/1441072953806835715 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Corner, A., Webster, R., & Teriete, C. (2015). Climate visuals: Seven principles for visual climate change communication (based on international social research). Climate Outreach. [Google Scholar]

- Cottle, S. (2009). Global crises in the news: Staging new wars, disasters, and climate change. International Journal of Communication, 3, 494–516. [Google Scholar]

- Culloty, E., Murphy, P., Brereton, P., Suiter, J., Smeaton, A. F., & Zhang, D. (2018). Researching visual representations of climate change. Environmental Communication, 13(2), 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, N. S., Thier, K., & Walth, B. (2021). Creating engagement with solutions visuals: Testing the effects of problem-oriented versus solution-oriented photojournalism. Visual Communication, 20(2), 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryugina, T., & Shurchkov, O. (2016). The effect of information provision on public consensus about climate change. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0151469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, K. L. (2014). From alarm to action: Closing the gap between belief and behavior in response to climate change. Available online: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/146 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Doherty, K. L., & Webler, T. N. (2016). Social norms and efficacy beliefs drive the alarmed segment’s public-sphere climate actions. Nature Climate Change, 6(9), 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskjær, M. F. (2017). Climate change communication in Middle East and Arab countries. In Oxford research encyclopedia of climate science. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Castrillo, C. (2014). Prácticas transmedia en la era del prosumidor: Hacia una definición del Contenido Generado por el Usuario (CGU). CIC. Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación, 19, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Castrillo, C., & Ramos, C. (2023). Social Web and Photojournalism: User-Generated Content of the Russo-Ukrainian War. Comunicar, 31(77), 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Castrillo, C., & Ramos, C. (2024). Post-photojournalism: Post-Truth challenges and threats for visual reporting in the Russo-Ukrainian war coverage. Digital Journalism, 13(1), 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Herrero, I. (2024). Análisis de la fotografía periodística del cambio climático: Las cumbres del clima en El País y The Guardian [Doctoral dissertation, University of Valladolid]. [Google Scholar]

- García Herrero, I., & Vicente Torrico, D. (2021). Cambio climático e imagen fotoperiodística: Evolución de su representación gráfica en el diario El País. AdComunica, (22), 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M. (2010). Media images of war. Media, War & Conflict, 3(1), 7–41. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, M. (2012). Images from nowhere: Visuality and news in 21st century media. In V. Depkat, & M. Zwingenberger (Eds.), Visual cultures—Transatlantic perspectives (pp. 197–228). Universitatsverlag Winter. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, L., Jörges, S., Mahl, D., & Brüggemann, M. (2024). Framing as a bridging concept for climate change communication: A systematic review based on 25 years of literature. Communication Research, 51(4), 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürsel, Z. D. (2016). Image brokers: Visualizing world news in the age of digital circulation. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, A., & Machin, D. (2008). Visually branding the environment: Climate change as a marketing opportunity. Discourse Studies, 10(6), 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P. S., & Feldman, L. (2016). The impact of climate change–related imagery and text on public opinion and behavior change. Science Communication, 38(4), 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, L. F., & Carnahan, D. (2020). Which bad news to choose? The influence of race and social identity on story selections within negative news contexts. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 97(3), 644–662. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. C., & Cooke, S. L. (2018). Environmental framing on Twitter: Impact of Trump’s Paris Agreement withdrawal on climate change and ocean acidification dialogue. Cogent Environmental Science, 4(1), 1532375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A. (2006). Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: The role of affect, imagery, and values. Climatic Change, 77(1), 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, B., & Erviti, M. C. (2015). Science in pictures: Visual representation of climate change in Spain’s television news. Public Understanding of Science, 24(2), 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L. S., & Azevedo, J. (2023). The images of climate change over the last 20 years: What has changed in the Portuguese press? Journalism and Media, 4(3), 743–759. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzoni, I., Nicholson-Cole, S., & Whitmarsh, L. (2007). Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Global Environmental Change, 17(3–4), 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, K. (2010). Beyond polar bears? Re-envisioning climate change. Meteorological Applications, 17(2), 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, S. M., Weber, E. U., Orlove, B. S., Leiserowitz, A., Krantz, D. H., Roncoli, C., & Phillips, J. (2007). Communication and mental processes: Experiential and analytic processing of uncertain climate information. Global Environmental Change, 17(1), 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mast, J., & Hanegreefs, S. (2015). When news media turn to citizen-generated images of war: Transparency and graphicness in the visual coverage of the Syrian conflict. Digital Journalism, 3(4), 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses-Fernández, M. D., & Torvisco, J. M. (2024). The emotional impact of journalistic images depicting natural disasters on affected populations. Journal of Media Ethics, 39(4), 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaris, P., & Abraham, L. (2001). The role of images in framing news stories. In S. D. Reese, O. H. Gandy Jr., & A. E. Grant (Eds.), Framing public life: Perspectives on media and our understanding of the social world (pp. 231–242). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Metag, J., Schäfer, M. S., Füchslin, T., Barsuhn, T., & Kleinen-von Königslöw, K. (2016). Perceptions of climate change imagery: Evoked salience and self-efficacy in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. Science Communication, 38(2), 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midberry, J., Brown, D. K., Potter, R. F., & Comfort, R. N. (2024). The influence of visual frame combinations in solutions journalism stories. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 101(1), 230–252. [Google Scholar]

- Midberry, J., & Dahmen, N. S. (2019). Visual solutions journalism: A theoretical framework. Journalism Practice, 14(10), 1159–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, S. D. (2006). “Regarding the pain of others”: Media, bias and the coverage of international disasters. Journal of International Affairs, 59(2), 173–196. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24358432 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Monahan, B., & Ettinger, M. (2018). News media and disasters: Navigating old challenges and new opportunities in the digital age. In H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, & J. Trainor (Eds.), Handbook of disaster research. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen, T. M., Hull, K., & Boling, K. S. (2017). Really social disaster: An examination of photo sharing on Twitter during the #SCFlood. Visual Communication Quarterly, 24(4), 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Pico, H. P., & León Anguiano, B. (2024). El sesgo de atención a las imágenes del cambio climático y su incidencia en el compromiso ciudadano. Palabra Clave, 27(4), e2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Ross Arguedas, A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2024). Digital news report 2024. Reuters Institute for the study of Journalism. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4sstjx8k (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Nurmis, J. (2017). Can photojournalism enhance public engagement with climate change? [Doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland]. [Google Scholar]

- Nurmis, J. (2021). Facing change: Human subjects in climate photojournalism. In F. Weder, L. Krainer, & M. Karmasin (Eds.), The sustainability communication reader (pp. 161–176). Springer VS. [Google Scholar]

- Ockwell, D., Whitmarsh, L., & O’Neill, S. (2009). Reorienting climate change communication for effective mitigation. Science Communication, 30(3), 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S. (2020). More than meets the eye: A longitudinal analysis of climate change imagery in the print media. Climatic Change, 163(1), 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S. J. (2013). Image matters: Climate change imagery in US, UK and Australian newspapers. Geoforum, 49, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S. J. (2017). Engaging with climate change imagery. In Oxford research encyclopedia of climate science. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, S. J., & Graham, S. (2016). (En) visioning place-based adaptation to sea-level rise. Geo: Geography and Environment, 3(2), e00028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S. J., & Nicholson-Cole, S. (2009). “Fear won’t do it” promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Science Communication, 30(3), 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S. J., & Smith, N. (2013). Climate change and visual imagery. WIREs Climate Change, 5(1), 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, S., Puente, S., & Grassau, D. (2015). La calidad periodística en caso de desastres naturales: Cobertura televisiva de un terremoto en Chile. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 21, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebich-Hespanha, S., & Rice, R. E. (2016). Dominant visual frames in climate change news stories: Implications for formative evaluation in climate change campaigns. International Journal of Communication, 10, 4830–4862. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. (2012). Visual methodologies. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rusgrove, K., & Catanzaro, M. (2020). Seeing climate change: Rethinking visual impact. The International Journal of the Image, 11(4), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, V., & Bossio, D. (2015). Using social media in the news reportage of war & conflict: Opportunities and challenges. The Journal of Media Innovations, 2(1), 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Montalbán, F. J. (2018). Fotografía de prensa. Del simulacro a la posverdad en la era digital. Index Comunicación, 8(1), 197–224. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10115/15758 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Scheufele, D. A., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shome, D., Marx, S., Appelt, K., Arora, P., Balstad, R., Broad, K., Freedman, A., Handgraaf, M., Hardisty, D., Krantz, D., Leiserowitz, A., LoBuglio, M., Logg, J., Mazhirov, A., Milch, K., Nawi, N., Peterson, Soghoian, A., & Weber, E. (2009). The psychology of climate change communication: A guide for scientists, journalists, educators, political aides, and the interested public. New York. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/3k2rna8m (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Social Media Working Group. (2018). Countering false information on social media in disasters and emergencies (technical report). US Department of Homeland Security. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/mrxapyjx (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Thomson, T. J., Angus, D., Dootson, P., Hurcombe, E., & Smith, A. (2020). Visual mis/disinformation in journalism and public communications: Current verification practices, challenges, and future opportunities. Journalism Practice, 16(5), 938–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toadvine, T. (2020). Climate Apocalypticism and the Temporal Sublime. In M. Kirloskar-Steinbach, & M. Diaconu (Eds.), Environmental ethics: Cross-cultural explorations (pp. 115–132). Verlag Karl Alber. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, R. M., & Anderson, A. K. (2013). Salience, state, and expression: The influence of specific aspects of emotion on attention and perception. In K. N. Ochsner, & S. M. Kosslyn (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of cognitive neuroscience: Volume 2: The cutting edges (pp. 11–31). Oxford Library of Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T., Valecha, R., Rad, P., & Rao, H. R. (2020). An investigation of misinformation harms related to social media during two humanitarian crises. Information Systems Frontiers, 23, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyheng, J., Tyagi, A., & Carley, K. M. (2021, June 21–25). Mainstream consensus and the expansive fringe: Characterizing the polarized information ecosystems of online climate change discourse [Conference contribution]. 13th ACM Web Science Conference 2021 (WebSci ’21), Virtual Event, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Vevea, N. N., Littlefield, R. S., Fudge, J., & Weber, A. J. (2011). Portrayals of dominance: Local newspaper coverage of a natural disaster. Visual Communication Quarterly, 18(2), 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vobič, I., & Tomanić Trivundža, I. (2015). The tyranny of the empty frame: Reluctance to use citizen-produced photographs in online journalism. Journalism Practice, 9(4), 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Corner, A., Chapman, D., & Markowitz, E. (2018). Public engagement with climate imagery in a changing digital landscape. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 9(2), e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. (2005). Cognitive theory. In K. Smith (Ed.), Handbook of visual communication research: Theory, methods, and media. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. (2025). The global risks report 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/39p5tf9h (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- World Meteorological Organization. (2023). WMO provisional state of the global climate 2023. Available online: http://tinyurl.com/3ahphryj (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- World Meteorological Organization. (2025). WMO confirms 2024 as warmest year on record at about 1.55 °C above pre-industrial level. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2njjb6wj (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Xu, Z., Laffidy, M., & Ellis, L. (2023). Clickbait for climate change: Comparing emotions in headlines and full-texts and their engagement. Information, Communication & Society, 26(10), 1915–1932. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer, B. (2004). The voice of the visual in memory. In K. R. Phillips (Ed.), Framing public memory (pp. 157–186). University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer, B., & Allan, S. (2011). Journalism after September 11. Routledge. (Original work published 2002). [Google Scholar]

| Media Outlet | Subscribers | Ownership | Articles CC 2023 | Articles DANA 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| El País | 350,000 | Grupo Prisa | 3947 | 928 |

| El Mundo | 115,000 | Unidad Editorial | 1239 | 920 |

| La Vanguardia | 77,000 | Grupo Godó | 2835 | 1714 |

| Source Type | CC 2023 | DANA Floods | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| UGC | 30 | 5 | 21 | 5.8 |

| Corporate/ONG | 89 | 14.7 | 22 | 6.1 |

| Freelance | 59 | 9.7 | 8 | 2.2 |

| Official source | 23 | 3.8 | 20 | 5.5 |

| Staff photographer | 114 | 18.8 | 62 | 17.1 |

| Stock/Photo agency | 79 | 13 | 17 | 4.7 |

| Wire service | 191 | 31.5 | 190 | 52.3 |

| N/A | 21 | 3.5 | 23 | 6.3 |

| Total | 606 | 100 | 363 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Castrillo, C.; Ramos, C. Photojournalist Framing in the Ecological Crisis: The DANA Flood Coverage. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020077

Fernández-Castrillo C, Ramos C. Photojournalist Framing in the Ecological Crisis: The DANA Flood Coverage. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(2):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020077

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Castrillo, Carolina, and Celia Ramos. 2025. "Photojournalist Framing in the Ecological Crisis: The DANA Flood Coverage" Journalism and Media 6, no. 2: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020077

APA StyleFernández-Castrillo, C., & Ramos, C. (2025). Photojournalist Framing in the Ecological Crisis: The DANA Flood Coverage. Journalism and Media, 6(2), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020077