1. Introduction

Social media has transformed political communication globally by providing new avenues for candidates to engage directly with voters, shape public discourse, and frame political issues. In Ghana, a country in West Africa known for its democratic stability and competitive elections since transitioning to multi-party democracy in 1992, social media platforms have become increasingly central to political campaigns. The fast-growing and changing media landscape of political campaigns in Ghana reflects broader global trends but is also shaped by Ghana’s unique socio-political and media environment. While digital media platforms have introduced new dynamics to political communication, these platforms are not the only means through which political messaging circulates in Ghana. Ghanaian campaigns are socially embedded processes where candidates engage directly with constituents through not only mass rallies but also courtesy calls on traditional leaders, occupational group meetings (such as with market associations and fisherfolk), and various forms of interpersonal interactions (

Bob-Milliar & Paller, 2023). These face-to-face encounters function as ritualistic and symbolic arenas for political engagement, often fostering grassroots participation and reinforcing political narratives rooted in Ghana’s historical experiences of collective mobilization (

Bob-Milliar & Paller, 2023).

Further, the role of pavement media—informal face-to-face discussions in marketplaces, religious spaces, and community gatherings—has been identified as a key link in Ghana’s broader media ecosystem. Political information, including misinformation, circulates across digital divides through these everyday communication spaces (

Gadjanova et al., 2022).

Building on this broader communicative landscape, social media platforms such as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and Instagram have become significant tools for political actors in Ghana, offering new avenues for candidates to amplify their messages, engage with diverse audiences, and frame political issues. The increasing use of social media in Ghanaian politics is partly driven by the rapid growth of mobile telephony and internet penetration, which has expanded access to digital platforms across the country (

Moreno et al., 2017).

Early studies noted that political parties in Ghana were slow to recognize and leverage the potential of social media for political engagement (

Van Gyampo, 2017). However, recent studies show that by the 2016 and 2020 election cycles, most parties had recognized the strategic importance of social media platforms, particularly Facebook and WhatsApp, for mobilization and voter outreach (

Dzisah, 2018;

Amankwah & Mbatha, 2019;

Anson Boateng & Buatsi, 2023). Traditional media, particularly radio, continues to play a crucial role in reaching rural populations and setting the political agenda, while social media is rapidly becoming the preferred platform for political engagement, especially among urban youth and educated demographics (

Gadjanova et al., 2019). Studies on the 2016 Ghana elections found that Facebook and WhatsApp were key social media platforms increasingly utilized by political parties (

Belley, 2020;

Adeiza, 2019;

Dzisah, 2018;

Boateng et al., 2020).

Interestingly, during the 2020 elections, three political parties—the National Democratic Congress (NDC), the New Patriotic Party (NPP), and the Convention People’s Party (CPP)—heavily invested in social media advertisements. From August to December 2020, Candidate Mahama of the NDC spent EUR 109,433 (approximately USD 95,747), Candidate Akufo-Addo of the NPP spent EUR 78,369 (approximately USD 68,823), and Candidate Greenstreet of the CPP spent EUR 1335 (approximately USD 1168) on these platforms (

Anson Boateng & Buatsi, 2023, p. 118). The study further identified Facebook and Instagram as the main platforms where these ads were placed due to their broad reach and multimedia capabilities for political engagement.

There is extensive scholarship on the use of social media for political campaigns; however, most studies have focused on European and Western contexts (

Fulgoni et al., 2016;

Enli, 2017;

Jensen, 2017;

Dimitrova & Matthes, 2018;

Bossetta, 2018;

Sahly et al., 2019). In the Ghanaian context, existing studies have primarily examined how political parties use social media platforms for voter mobilization and engagement (

Van Gyampo, 2017;

Moreno et al., 2017;

Dzisah, 2018,

2020;

Adeiza, 2019;

Amenyeawu, 2021;

Anson Boateng & Buatsi, 2023).

The goal of this paper, therefore, is to fill this gap and help boost understanding of how individual presidential candidates in Ghana utilize social media to frame key political issues—specifically, the economy and education—during the 2024 election campaign. Drawing on studies by

Anson Boateng and Buatsi (

2023) and

Moreno et al. (

2017), which identified Facebook, Instagram, and X (formerly Twitter) as widely used and influential platforms in Ghanaian political campaigns, this study uses multimodal discourse analysis (

Stewart et al., 2023;

Kress, 2010;

Light et al., 2018) and framing theory (

Entman, 1993) as the framework to examine content on these platforms with focus on issues related to the economy and education. In doing so, this study aims to reveal how these presidential candidates adopt social media to frame their campaign messages around the two dominant issues of public interest—economy and education—to engage voters.

1.1. Politics and Media in Ghana: Historical Background

The relationship between media and politics in Ghana dates back to the pre-independence era when the media was key in the struggle for decolonization. Prior to Ghana’s independence in 1957, newspapers and radio were central to political campaigns. The colonial and nationalist political movements relied heavily on print media, particularly newspapers, to disseminate information and mobilize support. Newspapers such as The Gold Coast Leader, The African Morning Post,

and The Ashanti Pioneer played significant roles in political discourse, shaping public opinion and nationalist movements (

Fosu, 2024). Notably, figures like Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first Prime Minister and President, used newspapers such as the Accra Evening News to challenge colonial authority and advocate for self-rule (

Akpojivi, 2014). Radio broadcasting, introduced in 1935 as a colonial relay station, later incorporated local languages to reach a broader audience (

Bourgault, 1995).

Following independence in 1957, Ghana’s political landscape saw various regimes, both civilian and military, with varying approaches to media control. Television broadcasting was not established in Ghana until 1965 under the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC). In the immediate post-independence period, the media was largely state-controlled, with successive governments using the press as a tool for nation-building and, at times, political suppression (

Twumasi, 1981;

Fosu, 2014;

Osei-Appiah, 2019).

The Third Republican Constitution, established after a period of military rule, sought to institutionalize press freedom by elevating the media to a crucial role within the constitutional framework (

Twumasi, 1981). This marked a significant shift from earlier political regimes, which had used the press as a tool for political control and influence (

Fosu, 2014). The democratization processes in Ghana, particularly after the Fourth Republic in 1992, brought renewed attention to the media’s role in fostering political participation and accountability (

Arthur, 2010). He further notes that media reforms were driven by the need to create an environment conducive to democratic governance (

Arthur, 2010). Media liberalization, thus, allowed for the proliferation of private media outlets, which diversified the information available to the public and facilitated more robust political debates (

Osei-Appiah, 2019;

Twumasi, 1981).

The rise of private media in the mid-1990s significantly transformed Ghana’s political communication landscape (

Afful, 2016). Before this period, the media environment was predominantly state-controlled, with institutions such as the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC) and state-owned newspapers, The Ghanaian Times and Daily Graphic, dominating the landscape. However, the liberalization of the media market in 1996 allowed for the establishment of over 149 radio stations, 450 newspapers, and multiple television channels, leading to a competitive and dynamic media environment (

International Institute for ICT Journalism, 2010).

Private media outlets, particularly private radio stations and newspapers like Daily Guide and Ghanaian Chronicle, quickly became central platforms for political discourse. These outlets provided alternative viewpoints that often challenged the narratives upheld by state-controlled media, thereby fostering a more diverse public sphere (

Afful, 2016). Radio became the most popular medium, with 90% of Ghanaians tuning in at least once in the past seven days, while 69% tuned in at least once a day (

Gadzekpo, 2005). Radio also serves as the primary source of information for the electorate, particularly in the Northern part of Ghana, where television and other media forms do not have an extensive reach (

Abdulai et al., 2020). They further note that radio’s wide accessibility and affordability make it the most relied-upon medium for political communication, mobilization, and spreading ideologies, especially during elections

Abdulai et al. (

2020).

While radio, newspapers, and television continue to play significant roles in Ghana’s media landscape today, the emergence of social media platforms has introduced a new dimension to political communication.

The two leading presidential candidates in the 2024 Ghanaian election, John Dramani Mahama of the NDC and Mahamudu Bawumia of the NPP present distinct backgrounds and experiences in their campaigns. Mahama, who served as President from 2012 to 2017, initially assumed the presidency as Vice President following the passing of John Evans Atta Mills. With decades of experience, including roles as a Member of Parliament and Minister for Communications, Mahama’s campaign draws on his history in public service, positioning him as a leader advocating for change. Bawumia, the incumbent Vice President since 2017, presents a contrasting profile with his background in economics and finance. Before entering politics, Bawumia worked as a central banker and holds a Ph.D. in economics, specializing in macroeconomics and development (

Wan Yee, 2016).

This study extends the existing literature by arguing that the framing of key public interest issues, specifically the economy and education (

Afrobarometer, 2024), on social media by these presidential candidates in the 2024 election offers new insights into how digital platforms are reshaping political campaign strategies in the country.

1.2. Ghana and Social Media Use: A Brief Overview

Since transitioning to a multi-party democracy in 1992, Ghana is viewed as one of the most peaceful and stable countries in West Africa. In 1957, Ghana became the first sub-Saharan country in colonial Africa to gain independence. Media outlets, particularly radio and television, played a critical role in educating voters and ensuring a smooth electoral process in Ghana (

Temin & Smith, 2002). However, they note that with the rise of digital technologies, including social media, traditional media now faces increased competition in shaping public discourse and setting the political agenda.

Survey data from the most recent Afrobarometer Round 10 (2024) confirm that social media is playing an increasingly important role in Ghana’s information landscape, particularly among certain demographic groups. According to the survey, 38.7% of Ghanaians report using the Internet every day, with usage significantly higher among urban residents and younger, more educated populations. Additionally, 91.8% of respondents own a mobile phone, and among these, 57.7% have internet-enabled devices, indicating substantial potential reach for digital campaign messages (

Afrobarometer, 2025).

In recent years, the Ghanaian government has made significant efforts to bridge the digital divide through various policy initiatives, such as the Digital Ghana Agenda, Mobile Money Interoperability, and Paperless Services in selected government institutions (

NCA, 2018). Moreover, Ghana is recognized for having one of the youngest populations in the world, with a median age of 20.7 years, according to the latest housing and population census by the Ghana Statistical Service (

GSS, 2021). This youthful demographic is generally more inclined to adopt and use digital technologies.

Building on these developments, Ghana’s Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector has experienced substantial growth, driven primarily by the widespread adoption of mobile phones and increased internet access. As of 2023, Ghana had approximately 41 million active mobile voice subscriptions, equivalent to about 134% of the population. This penetration rate exceeds 100% because many users hold multiple subscriptions (

International Trade Administration, 2023). Additionally, data subscriptions reached a penetration rate of around 78%, indicating a growing market for mobile internet and digital services (

International Trade Administration, 2023). Between 2014 and 2023, Ghana’s ICT sector has seen significant changes due to strategic government policies and investments. One major initiative is the Ghana Digital Acceleration Project (GDAP), funded by a credit of US

$200 million from the World Bank. This project aims to improve broadband access, modernize government digital services, and support innovation within Ghana’s digital ecosystem (

World Bank, 2022). Mobile money has also become important for financial inclusion in Ghana. By 2020, there were about 30 million registered mobile money accounts in Ghana, with transactions valued at more than US

$36 billion. This reflects significant progress in the use of digital technology for financial services (

International Trade Administration, 2023).

A study on social media use among university students in Ghana found that a significant majority were both aware of and actively using social media platforms for various purposes (

Apeanti & Danso, 2014). Their study revealed that 97.7% of the students surveyed were aware of Facebook, with 76.8% having an account on the platform (

Apeanti & Danso, 2014). X (formerly Twitter) and instant messengers (IMs) also showed considerable awareness, though the usage rates were lower.

In his study on social media adoption in Ghana,

Van Gyampo (

2017) found that political parties turned to platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp to communicate with voters, particularly targeting the youth, who make up over 60% of the voting population. However, he noted that they had yet to fully harness the potential of social media. A year later,

Dzisah’s (

2018) study revealed that most parties had recognized the cost-effectiveness of social media compared to traditional outlets like television, radio, and newspapers.

During the 2016 Ghanaian elections, social media platforms—especially Facebook and WhatsApp—were widely utilized by political candidates to mobilize voters, foster democratic engagement, and monitor electoral processes. WhatsApp, in particular, played a crucial role in organizing political teams, improving communication efficiency, and providing a secure channel for internal discussions (

Amankwah & Mbatha, 2019). They also found that students were motivated to engage with online political agendas primarily for surveillance purposes by using the features of these platforms to stay informed and interact with political content.

Despite insights from existing literature, particularly on the use of social media by political parties and the growing adoption of social media in Ghana, there is a gap in understanding how individual presidential candidates utilize these platforms to frame their campaign messages. As of 2024, the two leading presidential candidates have extensively adopted major social media platforms—X, Instagram, and Facebook—to communicate their campaign messages to voters. Therefore, this study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: How did the two major presidential candidates in Ghana, John Mahama and Mahamudu Bawumia, construct social media discourses to frame issues related to the economy and education during the 2024 presidential election?

RQ2: To what extent did platform-specific affordances shape the framing strategies and voter engagement of John Mahama and Mahamudu Bawumia on Facebook, Instagram, and X during the 2024 presidential election?

2. Materials and Methods

To address the research questions, the study adopts the walkthrough method developed by

Light et al. (

2018) as a data collection tool and supplemented with multimodal discourse analysis (

Keshavarzian & Stewart, 2025;

Stewart et al., 2023;

Kress, 2010;

Light et al., 2018). Using the walkthrough method (

Light et al., 2018), interactions between the candidates, the platforms, and their audiences were captured and archived, with a specific focus on framing strategies related to economic and educational policies.

The focus on John Mahama of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and Mahamudu Bawumia of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) reflects the dominance of these two parties in Ghana’s electoral politics. Since the return to multi-party democracy in 1992, the NPP and NDC have alternated in power, consistently emerging as the two leading political forces in presidential and parliamentary elections (

Fridy, 2007;

Bob-Milliar, 2012). Their candidates typically command a majority of the national vote share, making their campaign strategies central to understanding electoral communication dynamics in Ghana.

The social media platforms chosen for analysis—Facebook, Instagram, and X—were selected based on their substantial user bases and high engagement levels in Ghana (

Anson Boateng & Buatsi, 2023;

Moreno et al., 2017), which are critical for understanding the influence of the candidates’ messages. Although WhatsApp is also widely used in Ghana for sharing political information, its encrypted, closed-group format presents significant challenges for systematic data collection and content analysis (

Amankwah & Mbatha, 2019;

Lynch et al., 2022). Moreover, presidential candidates primarily rely on publicly accessible platforms to broadcast campaign messages to broader audiences, rather than closed intra-party group communication, making Facebook, Instagram, and X the most appropriate for this study.

The selection of economy and education as the focal issues in this study was guided by public opinion data from Afrobarometer Round 10. According to the 2024 Ghana survey results, unemployment (20.4%), management of the economy (13.1%), and rising cost of living (8.4%) were ranked as the most important problems that citizens wanted the government to address, with education also cited by 7.5% of respondents (

Afrobarometer, 2025). These findings indicate the salience of these issues in the public sphere during the 2024 election period.

The walkthrough method focuses on the technological affordances of platforms, where researchers systematically engage with app interfaces, noting user interactions and platform mechanisms (

Light et al., 2018). Extending this method, the study applies the digital multimodal walkthrough approach introduced by

Stewart et al. (

2023) to observe and archive multimodal content such as text, images, videos, stories, emojis, and other multimedia elements (see also

Keshavarzian & Stewart, 2025). The study collected data from 1 January 2024 to 7 December 2024, covering the entire election campaign period.

To systematically capture the dynamic content, the study used MacBook Pro 15-inch (2017) screen recording software to document the candidates’ social media pages: X, Instagram, and Facebook. MacBook Pro screen recording is a free screencast software that enables users to capture any portion of a computer screen through a snipping tool, making it easy to record content. This scrollable video capture method ensures the preservation of ephemeral content, such as Instagram Stories and tweets, before they are deleted or removed (

Keshavarzian & Stewart, 2025;

Stewart et al., 2023). Video streams were recorded randomly across four to five different days per candidate to ensure a representative sample of their social media activity. Each recording was at least one hour long. The novel use of video capture allows researchers to re-create the multimodal experience by ensuring that the content which is often ephemeral and subject to removal, is preserved for future analysis. This approach enhances the replicability of the study and enables other researchers to access and analyze the same content (

Stewart et al., 2023). The table below (

Table 1) shows the presidential candidates’ political affiliations, their status (former president vs. incumbent vice president), and their follower counts on each platform as of December 2024.

Facebook was the main social media platform for both candidates, as it had the highest number of followers compared to Instagram and X. These platforms allow for the dissemination of diverse media types, including posts, videos, and stories. Purposive sampling was used to select social media posts that specifically address the themes of economy and education. Purposive sampling is effective in focusing on content that is most relevant to the research questions and allows the study to concentrate on posts that highlight significant framing strategies related to the selected issues (

Stewart et al., 2023).

In addition to dynamic content such as stories and videos, static screenshots were captured for any content that could be categorized under the issues of economy and education. This multimodal data was compiled into shareable presentation slide decks using the graphic design platform Canva. Within these decks, significant posts and patterns relevant to the framing strategies were highlighted and bookmarked for detailed analysis. The structure ensures consistent revisitation of material and provides a thorough and replicable analysis of social media interactions (

Stewart et al., 2023). The final recordings and screenshots were stored in Microsoft OneDrive, where each platform and candidate were organized into folders categorized by a focus on economic or educational issues.

The digital multimodal walkthrough method provides a more comprehensive representation of social media interactions by preserving content as a continuous stream of information rather than isolated texts or images. This approach enhances the understanding of the dialogical nature of discourse construction and allows researchers to analyze content in its original multimodal context. While individual researchers can curate content, the scrollable video format and shareable presentation slide decks ensure that others can cross-check purposive sampling decisions and discourse analysis, therefore, reducing the potential for bias (

Stewart et al., 2023). Additionally, the use of data archiving tools facilitates a structured and collaborative environment and enables researchers to systematically compile, organize, and review material independently or as part of a research team (

Stewart et al., 2023).

4. Results

This study examines how Ghana’s two leading presidential candidates, John Mahama of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and Mahamudu Bawumia of the New Patriotic Party (NPP), framed issues of economy and education on social media during the 2024 election campaign. By analyzing their messaging strategies on Facebook, Instagram, and X, the study illustrates how their issue-framing strategies engaged voters through platform affordances, visual narratives, and interactive discourse. The findings of the study reveal three core dynamics in the framing strategies of both candidates: (1) contrasting economic narratives (‘Resetting Ghana’ vs. ‘It Is Possible’), (2) competing visions of education (reform vs. continuity), and (3) platform-specific engagement patterns. These findings offer insight into how political actors leverage digital affordances beyond simple messaging tools into structured framing mechanisms and strategically construct narratives to shape public discourse and influence voter engagement.

4.1. Contrasting Economic Narratives: ‘Resetting Ghana’ vs. ‘It Is Possible’

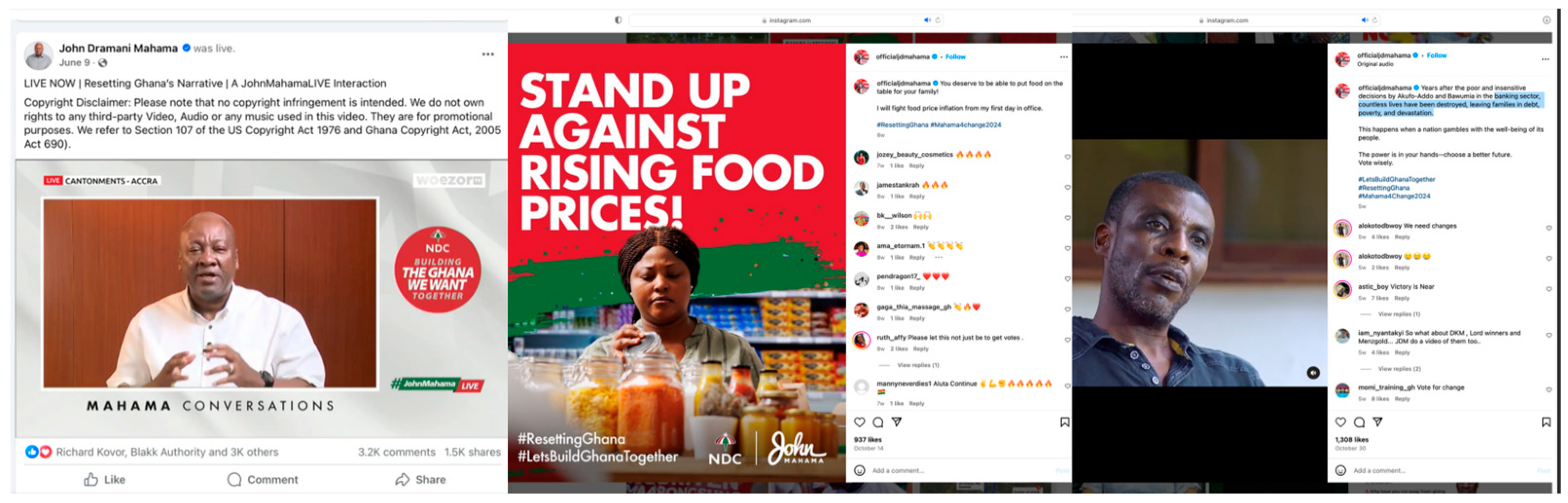

Mahama and Bawumia employed contrasting economic framing strategies, with Mahama positioning himself as the opposition challenger focused on economic recovery through his ‘Resetting Ghana’ narrative, while Bawumia, as the incumbent candidate, framed himself as an advocate for continuity and progress under ‘It Is Possible’ slogan.

Mahama’s economic discourse was framed around the theme of ‘resetting’ the economy by employing a crisis-framing strategy that portrayed the current administration as responsible for Ghana’s economic hardship. His campaign’s dominant hashtag, #ResettingGhana, was consistently used across platforms to reinforce this narrative. By highlighting economic mismanagement, unemployment, and inflation as causal issues, Mahama positioned himself as the leader capable of restoring economic stability.

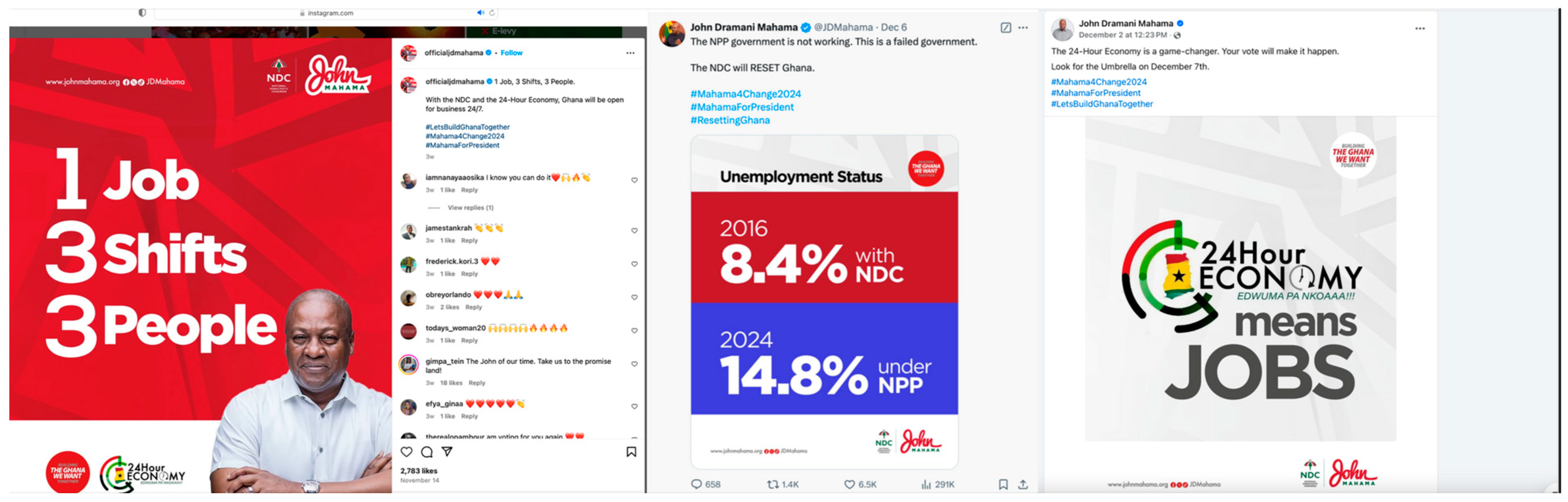

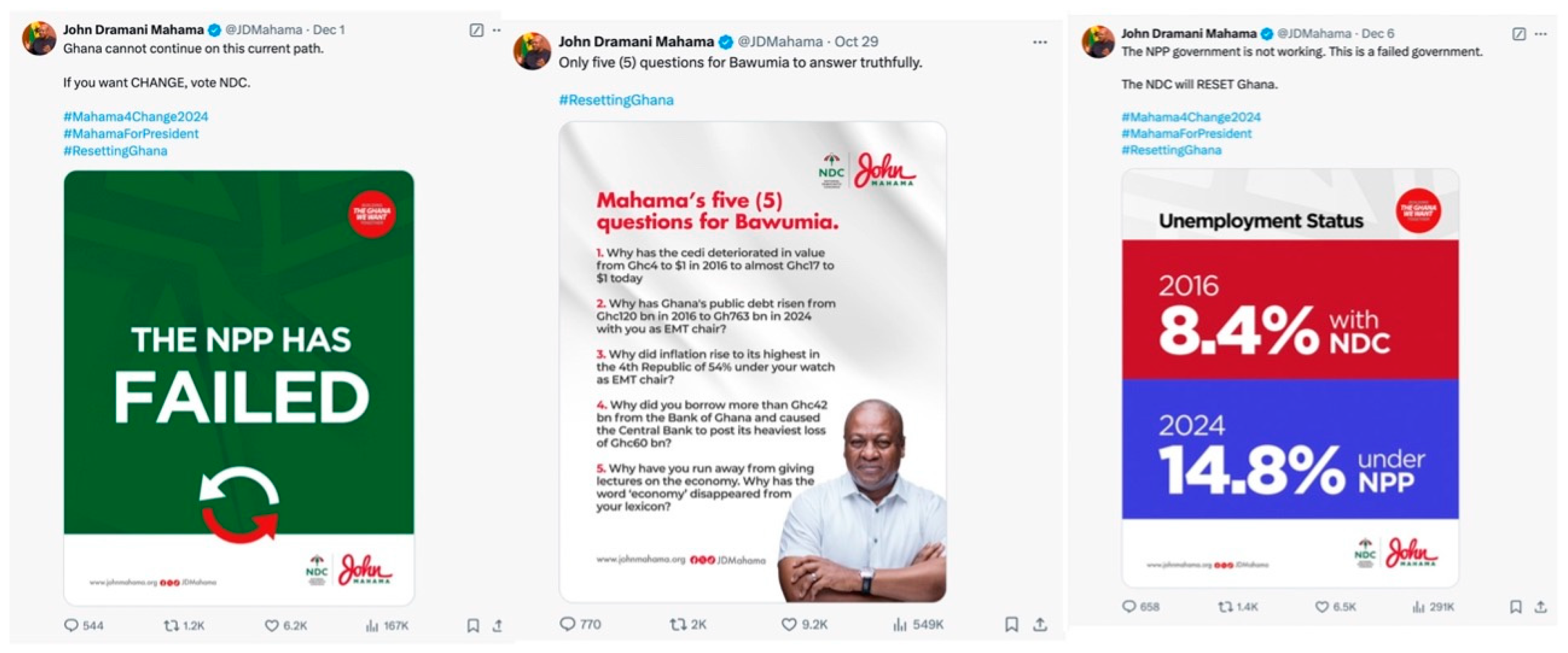

The ‘24-h economy’ was Mahama’s most dominant policy proposal, which he framed as the solution to Ghana’s economic crisis. This was consistently reinforced through hashtags (#Mahama4Change, #ResettingGhana #MahamaForPresident), graphic flyers, and videos across Instagram, Facebook, and X. His posts often featured unemployment statistics, policy proposals, and economic comparisons between his tenure and the current administration.

He consistently positioned the ‘24-h economy’ as a game-changing intervention that would create jobs, expand production, and stabilize the economy (see

Figure 1 below).

Figure 1 illustrates how Mahama frequently frames Ghana’s economic challenges and his proposed 24-h economic solution. The Instagram post (first image from the left) presents his vision for job creation through the 24-h economy policy, using the slogan “1 Job, 3 Shifts, 3 People”. The X post (middle image) compares Ghana’s unemployment rate, showing 8.4 percent during his presidency in 2016 and 14.8 percent under the NPP in 2024. The Facebook post (third image) reinforces his campaign’s central message, presenting the “24-Hour Economy” as a transformative policy that will generate jobs and economic opportunities.

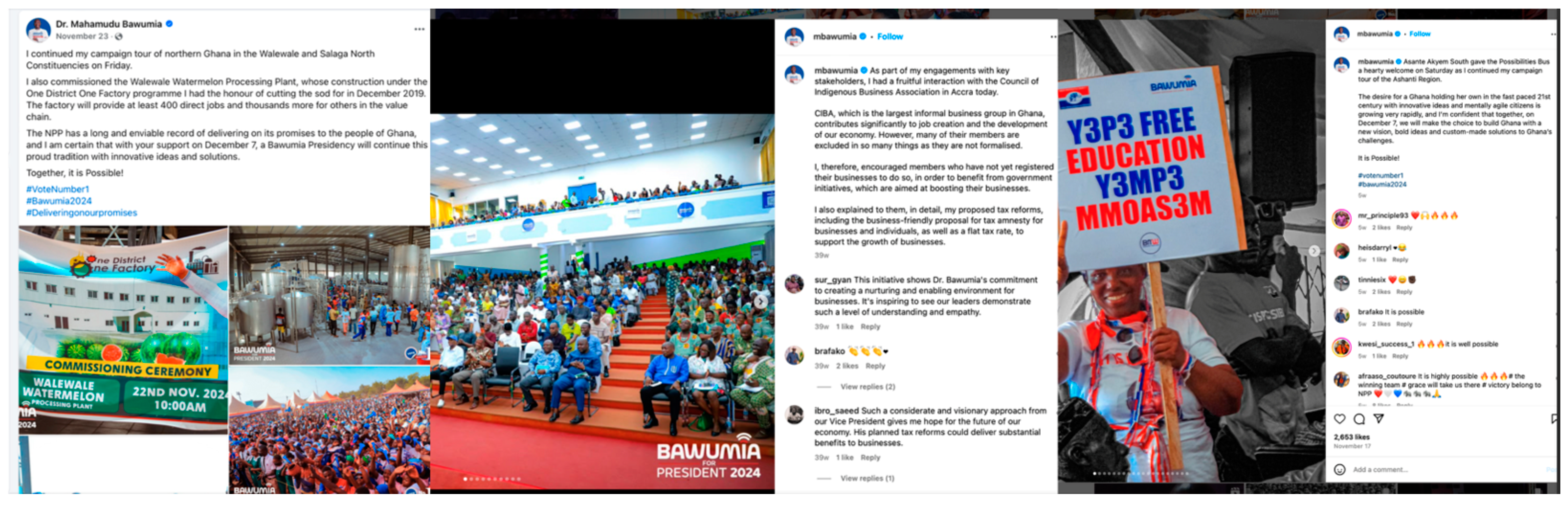

In contrast, Bawumia’s campaign framed the economic narrative around continuity and technological transformation, using #ItIsPossible as a central theme. Rather than directly addressing criticisms of economic hardship, Bawumia’s campaign focused on showcasing his achievements as Vice President, particularly in digitalizing the economy and improving governance efficiency. He presented the economy through a lens of progress and innovation, often depicting Ghana as being on a transformative journey where technological advancements would drive economic prosperity (see

Figure 2). His campaign slogan, “It is Possible”, conveyed optimism, forward-thinking leadership, and digital solutions as the foundation for economic growth. Unlike Mahama’s strong opposition framing, Bawumia frequently highlighted his role in modernizing Ghana’s economy through digitalization, referencing initiatives such as the Ghana Card as a national identity and economic tool, Mobile Money Interoperability for seamless digital transactions, e-taxation and e-pharmacy systems, and the introduction of the Ghana Digital Property Address System. Bawumia’s social media posts often framed these policies as foundational to Ghana’s economic future, repeatedly stating that Ghana was already on the path to a digital economy that would drive transformation.

Figure 2 illustrates how Bawumia frequently frames Ghana’s economic future through digitalization and private-sector engagement. The X post (first image from the left) highlights the launch of the ‘CitizenApp’, where he asserts that digital innovation is crucial for improving governance efficiency and public service accessibility. The Instagram post (middle image) showcases his introduction of ‘myCreditScore’, a credit scoring system aimed at improving financial inclusion and access to credit for all Ghanaians. The Facebook post (right image) reinforces his position that the private sector is the foundation of economic growth, as he engages with business leaders to outline tax reforms and policies aimed at fostering entrepreneurship. These posts align with his broader and frequent campaign message of continuity, economic modernization, and technological advancement as key drivers of Ghana’s future development.

Notably, unlike Mahama’s structured and visual approach, Bawumia’s economic messaging focused more on achievements and was primarily text-based, with an emphasis on listing the government’s accomplishments. His visuals primarily consisted of images from commissioning events, speaking engagements, and community interactions, rather than infographics that broke down policies. Also, his campaign’s hashtag use was inconsistent, shifting between #Bawumia2024, #BoldSolutionsForOurFuture, and #ItIsPossible, which made his branding less consistent than Mahama’s campaign.

It was observed across the dataset that Mahama did not merely highlight economic struggles across his social media platforms; he positioned himself as a candidate focused on practical solutions by presenting clear and policy-based interventions. His “24-h economy” was the centerpiece of his economic messaging, framed as a transformative policy that would create jobs, expand production, and stabilize the economy. The use of repetition and visual branding, including infographics illustrating job creation policies and proposed tax reductions, strengthened his economic argument. Mahama’s hashtags (#ResettingGhana, #Mahama4Change2024, #LetsBuildGhanaTogether) created a unified campaign identity, which ensured that his messaging remained consistent and was easily searchable across platforms.

Additionally, Mahama contextualized the 24-h economy within Ghana’s economic crisis, framing it as a solution to inflation, currency depreciation, and youth unemployment. His infographics provided comparative statistics, such as the claim that unemployment had risen from 8.4% in 2016 to 14.8% under the NPP government, effectively framing his opponent as responsible for economic mismanagement. His strategy was highly interactive and policy-focused, using specific issue frames such as “economic reset”, “24-h economy”, and “job creation” to position himself as a reformer responding to Ghana’s economic crisis.

Bawumia, on the other hand, focused on past achievements rather than outlining a clear vision for the future. His posts frequently highlighted his government’s successes in digitalization but lacked a consistent campaign theme, which made his message less focused and persuasive compared to Mahama. While he used videos and infographics, they were not organized around a strong central message. Also, Bawumia’s inconsistent use of hashtags made it more difficult to reinforce key campaign messages across platforms.

4.2. Competing Visions of Education: Reform vs. Continuity

Across the dataset, the candidates framed education differently, with Mahama advocating for systemic reform and policy expansion under his education agenda, while Bawumia positioned himself as supporting continuity and the existing Free Senior High School (SHS) policy.

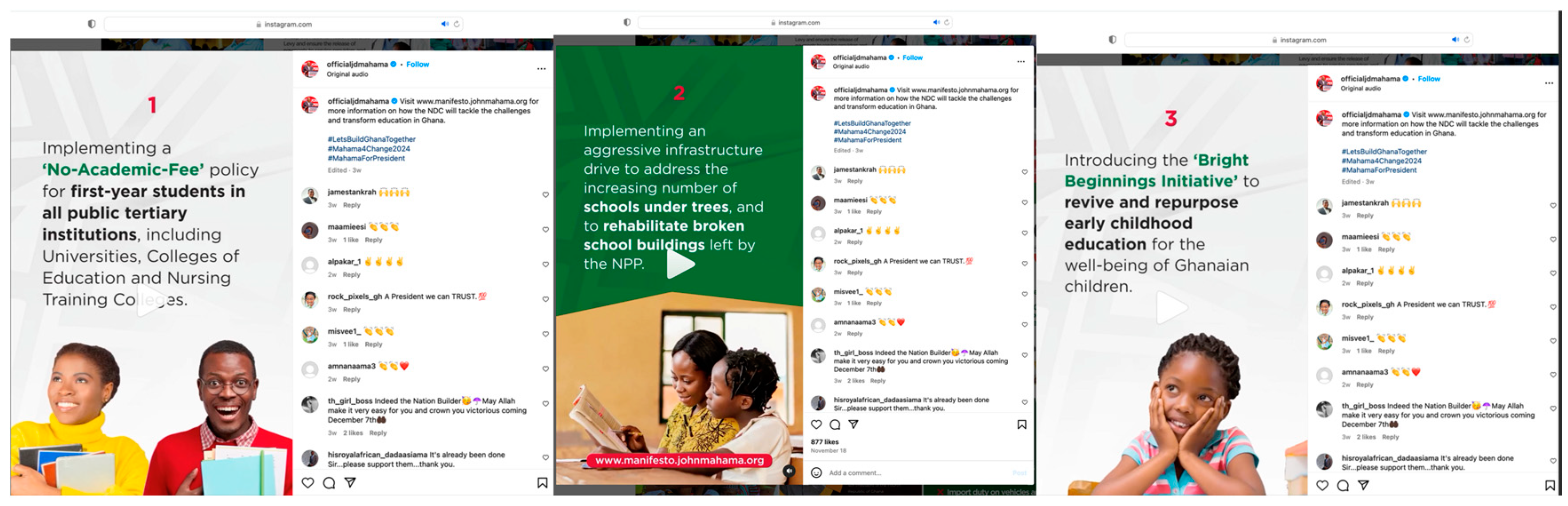

Mahama’s social media campaign proposed a series of targeted interventions aimed at reforming and restructuring the education sector. These included the “No-Fees-Stress” policy, which sought to eliminate first-year tuition fees in public universities, the reintroduction of the ‘Student Loan Trust Plus’ to provide financial support for tertiary students, a ‘National Apprenticeship Programme’ to equip young people with technical and vocational skills, and the establishment of a ‘Women’s Development Bank’ to offer financial support for women-led educational initiatives.

Through a series of social media posts, Mahama argued that the Free SHS policy—one of the NPP’s flagship initiatives—was poorly implemented and unsustainable in its current form. To address these challenges, he proposed targeted interventions, including free tertiary education for Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) and increased investment in technical and vocational education. His strategy also involved engaging with teacher unions and hosting interactive live sessions on Facebook (“Mahama Conversations”) to discuss these proposed reforms. Other frequent posts focused on teacher welfare, including a proposed 20% salary bonus for teachers who accept positions in rural schools.

His framing of education was structured, highly interactive, and supported by visual representations of his policies (see

Figure 3). He used infographics, video clips, and direct Q&A engagements with students to reinforce his arguments. The use of testimonial short reel videos from students, educators, and policy experts strengthened his messaging and created an emotional connection with voters. Also, Mahama’s posts often carried messages such as “Our youth are getting increasingly frustrated with the lack of jobs and education opportunities. We will give them the future they deserve”. He repeatedly used hashtags such as #LetsBuildGhanaTogether and #MahamaForChange to create a unifying digital movement around his educational policies. Additionally, Mahama’s campaign incorporated detailed policy explanations through infographics that outlined budget allocations for education.

Figure 3 shows how Mahama frequently centered his education campaign on affordability and infrastructure development. The first Instagram post (left) highlights his proposal for a “No-Academic-Fee” policy, aimed at eliminating first-year tuition fees for public tertiary students. The second post outlines his plan to improve school infrastructure by addressing the issue of schools under trees and rehabilitating abandoned school buildings. The third post promotes the “Bright Beginnings Initiative”, which focuses on strengthening early childhood education.

However, the incumbent Vice President Bawumia centered his education campaign on maintaining and expanding the Free SHS policy, which he presented as the NPP’s flagship achievement (see

Figure 4 below). His social media posts warned that a Mahama presidency would jeopardize the program.

Bawumia framed his education campaign around the continuity and protection of the Free Senior High School (SHS) policy. His social media posts across Instagram, Facebook, and X highlight the government’s achievements in providing free education to over 1.8 million Ghanaians. By emphasizing the need to ‘protect’ Free SHS, this approach created a sense of urgency among voters who had directly benefited from the policy, warning that a change in leadership could put Free SHS at risk. Through the use of bold text, hashtags such as #Bawumia2024 and #VoteNumber1, and long documentary video content featuring classroom scenes, Bawumia’s campaign visually communicated his commitment to maintaining and improving the initiative. His social media captions frequently reinforced this message, stating, “We cannot allow Free SHS to be taken away. Vote to protect the future of Ghana’s children”. While this strategy effectively promoted continuity and leveraged the incumbency advantage, it lacked the detailed policy proposals that characterized Mahama’s campaign.

Notably, Mahama’s approach was more structured and policy-focused, whereas Bawumia’s strategy relied more on long videos and images of students benefiting from Free SHS, featuring testimonials from teachers, parents, and young people. His hashtag use was inconsistent, shifting between #Bawumia2024, #BoldSolutionsForOurFuture, and #ItIsPossible, which weakened the overall branding consistency of his campaign compared to Mahama’s. Rather than providing in-depth policy explanations, Bawumia’s educational messaging focused on personal stories and visual narratives. His posts often highlighted STEM education, digital literacy, and the expansion of technical training programs, showcasing students using government-provided tablets and ICT tools to emphasize his administration’s role in promoting innovation. The debate over Free SHS became a contest between advocating for reform and defending policy continuity. The table below (

Table 3) compares the candidates’ engagement levels (likes, comments, shares, views) on social media content related to economic and educational policies.

Table 3 shows key differences in how Mahama and Bawumia’s economic and educational policy messages resonated with social media audiences across platforms. Mahama consistently generated higher interaction across Facebook, Instagram, and X, particularly when discussing economic policies such as the 24-h economy, job creation, and taxation. His content was more interactive, with strong engagement through comments and shares, which suggests that his economic framing sparked discourse and audience participation. His Instagram Reels, in particular, outperformed static posts, which indicates that short-form video content played a crucial role in audience engagement.

Bawumia’s economic messaging, while generating significant interaction, trailed behind Mahama, especially in audience discourse on X and comment engagement on Facebook. His campaign leaned more on descriptive tweet threads rather than direct debates, which may explain the lower engagement levels. His Instagram engagement was also lower, which suggests that his content was less optimized for the platform’s visual affordance.

On education, Mahama again saw higher engagement, particularly on Instagram and X, where interactive features such as Q&A sessions (“Mahama Conversations”) facilitated real-time voter engagement. His focus on policy specifics, such as free tertiary education and apprenticeship programs, likely contributed to this traction (see also

Table 4). In contrast, Bawumia’s educational posts were more event-driven and less discussion-oriented, leading to comparatively lower audience participation. His messaging largely consisted of summarizing policy achievements rather than actively engaging in debates or Q&A sessions, which may have contributed to the lower engagement on X.

Table 4 illustrates the engagement metrics for selected social media posts by Mahama and Bawumia on X, Instagram, and Facebook. The posts were specifically chosen to represent their respective messaging on key topics such as the economy, education, and job creation. The metrics include view count, likes, comments, and shares/retweets. The percentages reflect the ratio of likes, comments, and shares/retweets relative to the total view count.

The table shows that Mahama’s engagement metrics were generally higher than Bawumia’s, particularly on Facebook, where Mahama’s educational posts saw significant interaction. This is likely because Mahama’s posts were more interactive, featuring strategies such as Q&A sessions and policy specifics, which encouraged more engagement. In contrast, Bawumia’s posts were less interactive and more focused on summarizing achievements, which may have contributed to comparatively lower audience engagement.

4.3. Specific Platform Affordances and Engagement Strategies

Social media platform affordances significantly shaped the ways in which Mahama and Bawumia engaged with voters (see

Table 5). Each platform presented distinct opportunities for narrative construction, audience interaction, and strategic message dissemination, influencing the overall effectiveness of their digital campaign approaches.

Notably, Mahama’s campaign customized its messaging to match the strengths of each platform (see

Figure 5). In contrast, Bawumia’s strategy was mostly event-focused, had limited interactive elements, and lacked a clear approach to adapting content for different social media platforms.

On Facebook, Mahama utilized Facebook Live sessions, branded as ‘Mahama Conversations’, to engage voters directly in real-time discussions about economic and educational policies. This interactive format allowed for two-way communication and reinforced his image as a candidate who was open to public discourse and policy debate. His use of infographics and detailed captions provided voters with clear explanations of his policy proposals and ensured that his messaging was both accessible and informative. Furthermore, his consistent hashtag usage created a coherent digital identity and made his campaign themes easily searchable and recognizable. On the other hand, Bawumia used Facebook primarily for event updates, such as project inaugurations, campaign tours, and past achievements (see

Figure 6). His engagement was more one-directional, focusing on highlighting accomplishments rather than fostering dialogue. Additionally, his inconsistent hashtag usage weakened his campaign message and made it less unified across the platform.

On Instagram, Mahama’s campaign was engaging and appealing to young voters, using short video reels, emotional testimonials, and well-organized graphics to present his economic and educational policies. This structured visual messaging made his campaign content more engaging and accessible.

Bawumia relied more on static photo updates from rallies and community engagements. His posts lacked structured issue-based framing, with fewer infographics and minimal direct policy communication.

Bawumia utilized Facebook for event-driven updates and Instagram for economic engagement, showcasing large-scale economic projects, business-friendly policies, and the continuation of Free SHS.

Mahama actively engaged in real-time debates, using data-driven critiques, rhetorical questions, and direct confrontations to challenge his opponent’s record. His posts were structured around economic statistics and critiques of government failures. Also, his consistent use of hashtags kept his messages connected and ensured his arguments remained visible and easy to follow in political discussions (see

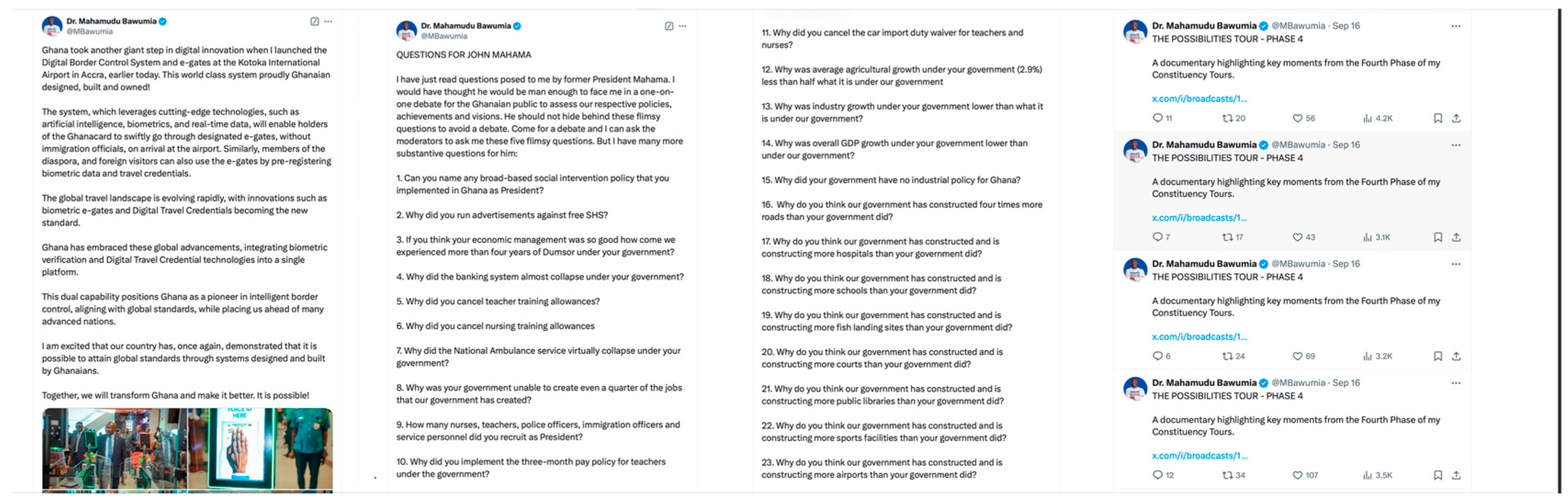

Figure 7).

Bawumia’s X activity was more descriptive and event-focused, often summarizing speeches and campaign events rather than directly engaging in policy debates. While he utilized X Broadcasts for speech dissemination, he did not leverage the platform for real-time interaction which reduced his engagement in direct political discourse. His messaging lacked structured issue-based framing and made his digital communication less impactful in shaping political narratives (see

Figure 8).

Overall, Mahama’s ability to adapt his communication style to different platform affordances allowed him to effectively frame economic and educational issues while maintaining a clear and consistent campaign identity. Bawumia, however, focused more on traditional campaign updates and event-driven communication, incorporating fewer interactive elements and a less structured approach to presenting policy. This difference in digital strategy affected voter engagement with their messages and shaped the overall discourse of the election campaign.

5. Discussion

Social media has become a key platform for political campaigns, where candidates not only communicate policies but also construct narratives that shape public perception. The findings of this study show significant differences in how John Mahama and Mahamudu Bawumia utilized digital platforms to shape discussions around economic and educational policies during the 2024 Ghanaian presidential election. Their strategies reflected broader political positioning, with Mahama, the former president, leveraging social media to present himself as a reformist championing economic recovery and educational reform, while Bawumia, the incumbent vice president, framed his campaign around continuity and technological progress. The findings reveal that the effectiveness of a candidate’s political campaign on social media is closely linked to how well they tailor their messaging to the unique features of each platform. Thus, by strategically aligning their content with platform-specific affordances, candidates can maximize their reach and voter engagement.

Across the dataset, it was observed that Mahama’s campaign adapted to the affordances of each social media platform, using Facebook Live for interactive Q&A sessions, Instagram Reels for visually engaging policy presentations, and X for real-time debates and direct voter interaction (see

Figure 1,

Figure 3,

Figure 5 and

Figure 7). This tailored approach allowed him to create a more engaging campaign space, where voters felt actively involved in discussions about economic and educational policies. In contrast, Bawumia’s digital strategy was less structured and relied more on showcasing campaign events, such as rallies, project inaugurations, and public appearances, rather than fostering direct interaction with voters (see

Figure 2,

Figure 4,

Figure 6 and

Figure 8). His approach focused more on visibility through social media posts that summarized campaign events and speeches rather than engaging in interactive policy discussions. Notably, his lower engagement across Facebook, Instagram, and X suggests that a passive approach to digital campaigning is less effective in generating voter engagement and fostering meaningful political discourse compared to a strategy that effectively utilizes platform-specific affordances (see

Table 4 and

Table 5).

Meanwhile, engagement in digital platforms is not solely dependent on content strategy.

Royal’s (

2023) product-engagement model offers a useful framework for understanding how engagement is shaped by three key factors: (1) interface affordances (how platforms are designed for interaction), (2) data models (how user activity and preferences are structured), and (3) algorithms (how content is distributed and made visible to users). Mahama’s ability to actively engage voters across platforms aligns with this model, as his campaign strategically leveraged the affordances of Facebook Live, interactive comment sections, and hashtag-based discussions on X to create highly visible and participatory engagement spaces.

Interestingly, Mahama framed his economic message around the “Resetting Ghana” campaign slogan, which positioned him as the candidate for economic recovery and reform. His messaging portrayed the current administration as responsible for Ghana’s economic hardship while presenting his proposed ‘24-h economy’ policy as the solution for job creation, increased productivity, and overall economic stabilization. His posts frequently used comparative statistics, bold infographics, and testimonial videos to reinforce this argument, which made his economic messaging both data-driven and visually compelling.

On the other hand, Bawumia focused on continuity and technological transformation by frequently posting the NPP’s digital governance achievements as evidence of ongoing economic progress. However, his approach lacked structured visual narratives and deep policy explanations which made his messaging less detailed and less interactive than Mahama. This finding supports the argument that framing policies through structured and visually engaging content on social media enhances voter engagement and message retention (

Bronstein et al., 2018;

Farkas & Bene, 2021).

Similarly, in the discussion of educational policies, Mahama framed his campaign around reform and expansion, promising interventions such as free tertiary education for Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) and increased investment in technical and vocational training. His campaign was highly interactive, with live-streamed Q&A sessions, structured infographics, and direct engagements with teacher unions and students, which created a sense of policy transparency and accessibility. However, Bawumia focused on preserving and expanding the Free SHS policy and frequently warned that Mahama’s presidency could lead to its reversal. His posts relied more on emotional appeals and testimonial videos from beneficiaries, focusing on the continuation of existing policies rather than proposing new educational interventions. While this approach effectively mobilized supporters who benefited from Free SHS, it lacked specific policy breakdowns and detailed implementation strategies which made it less detailed and comprehensive compared to Mahama’s more structured policy discourse.

The findings of the study further highlight the importance of maintaining a clear and consistent message across social media platforms for political campaigns. Mahama used consistent hashtags (#ResettingGhana, #Mahama4Change, #LetsBuildGhanaTogether), which kept his messages searchable, unified, and easily recognizable across platforms. In contrast, Bawumia frequently changed hashtags (#Bawumia2024, #BoldSolutionsForOurFuture, #ItIsPossible), which weakened the overall focus of his campaign and made it harder to establish a central message.

This study argues that political candidates who integrate structured, interactive, and visually engaging social media strategies are more effective in shaping public discourse and mobilizing voter engagement. Mahama’s higher engagement levels across platforms suggest that digital political campaigns require more than just content dissemination—they demand active participation, clear messaging structures, and tailored platform strategies to effectively connect with voters.

As social media continues to influence political campaigning, these findings suggest that political candidates must prioritize real-time engagement, data-driven narratives, and visual storytelling to effectively frame policy discussions and shape voter perceptions.

While this study focused on how presidential candidates framed economic and educational issues through their official social media accounts, it is important to acknowledge that broader political and economic contexts may influence how such frames are constructed and received by the electorate. In Ghana, the 2024 elections took place amid ongoing economic challenges, including high inflation, unemployment, and concerns over the rising cost of living—issues that were also reflected as top public priorities in Afrobarometer survey data (

Afrobarometer, 2025). These conditions likely shaped public expectations and may have influenced how candidates chose to present their messages, particularly in terms of problem definitions and proposed solutions. Although this study did not conduct a comparative analysis with previous Ghanaian elections, such as the 2016 contest, or with other African cases where economic crises played a significant role in electoral outcomes, these dynamics remain important contextual factors. Future research could explore how incumbency or opposition status may shape framing strategies during periods of economic difficulty, particularly whether opposition candidates tend to emphasize calls for change and accountability, while incumbents focus on continuity and policy achievements.

Further, the difference observed in how Mahama and Bawumia used social media during the 2024 campaign may also reflect broader patterns seen in other elections in Ghana and across Africa. Previous research found that the NPP was more effective in using social media in the 2016 and 2020 Ghanaian elections, particularly for engaging urban youth and shaping political narratives (

Gadjanova et al., 2019,

2022). In contrast, the 2024 election shows a shift, with Mahama, as the opposition candidate, adopting a more structured, interactive, and engaging social media strategy than Bawumia, the incumbent vice president. This has also been observed in other African elections, where opposition candidates have used social media as a tool to mobilize support and challenge incumbents. For example, in Zambia’s 2021 election, the opposition party relied on social media to disseminate information and support offline organizing efforts in a media environment that largely favored the incumbent (

Lynch & Gadjanovaa, 2022). Similarly, in Kenya’s 2022 presidential election, candidates adopted segmented digital strategies by delegating certain types of messaging to affiliated influencers (

Abboud et al., 2024). These examples suggest that opposition candidates may often invest more in digital engagement because they face disadvantages in other forms of political communication. Although this study did not directly compare these cases, the similarities highlight how political status—whether a candidate is in government or in opposition—can shape social media strategies.

Table 6 shows summary of the 2024 Ghana presidential election results for the two major candidates (results from 275 out of 276 constituencies) as reported by the Ghana Electoral Commission on 10 January 2025. With Mahama winning the 2024 election with 56.55% of the vote, future research could also examine how social media engagement translates into voter behavior and whether high digital engagement correlates with electoral success.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how the two leading candidates in Ghana’s 2024 presidential election, John Mahama and Mahamudu Bawumia, used social media to frame issues related to the economy and education. The findings reveal key differences in their digital campaign strategies and highlight the critical role of platform-specific affordances in shaping voter engagement. Mahama’s campaign effectively leveraged interactive and visually compelling content, structured messaging, and consistent hashtags across Facebook, Instagram, and X to frame himself as the candidate for Ghana’s economic recovery and educational reform. His messaging around the “24-h economy” and job creation was reinforced with statistical comparisons, infographics, and real-time voter engagement, which made his campaign more issue-focused and interactive. In contrast, Bawumia’s strategy relied heavily on showcasing past achievements and defending policy continuity, but it lacked the structured engagement and clear thematic consistency seen in Mahama’s campaign. His inconsistent use of hashtags and less interactive approach weakened his ability to sustain a unified digital campaign message.

These findings can also be situated within the broader historical and ideological landscape of Ghanaian party politics, providing additional context for the framing choices observed. Beyond its specific focus on the 2024 Ghanaian presidential election, this study contributes to a broader understanding of how party identities and political traditions may inform contemporary campaign strategies. The framing patterns observed—where Mahama, representing the NDC, positioned himself as a reformist advocating economic recovery and educational reform, while Bawumia, representing the NPP, emphasized continuity and policy preservation—reflect the established political orientations of these parties. Previous research has shown that the NDC generally aligns with social democratic principles, with roots in the post-revolutionary PNDC era under Jerry John Rawlings, often emphasizing social welfare, reform, and redistribution (

Bob-Milliar, 2012). In contrast, the NPP has historically drawn on the Danquah-Busia-Dombo tradition, advocating market-oriented policies, private sector-led growth, and constitutional governance (

Fridy, 2007). These ideological legacies may help explain the candidates’ framing choices during the 2024 campaign, particularly in how they positioned themselves around issues of economic management and educational policy.

While this study offers insights into the use of social media for issue framing in Ghanaian presidential campaigns, its findings may also be relevant to similar electoral contexts across Africa and other regions where opposition and incumbency dynamics intersect with economic challenges. However, the scope of this research is limited to a single election cycle, two candidates, and selected key issues (economy and education). The analysis was also restricted to official candidate accounts, which may not capture the full spectrum of campaign messaging circulating through affiliated networks or unofficial channels. Further research could explore these dynamics through comparative studies across different electoral contexts or by examining how these framing strategies evolve over time.

Building on previous studies (

Van Gyampo, 2017;

Dzisah, 2018;

Amankwah & Mbatha, 2019), which found that Ghanaian political parties are increasingly relying on digital platforms for mobilization and engaging young voters, this study argues that Ghana’s digital campaign strategies have evolved beyond simple messaging tools into structured framing mechanisms, where presidential candidates strategically construct narratives, debate political issues to shape public discourse and directly influence voter engagement.

The study also suggests that an interactive, platform-adaptive digital strategy can enhance a candidate’s ability to connect with voters, frame policy discussions effectively, and establish a strong campaign identity. Mahama’s victory with 56.55% of the 2024 Ghana electoral vote suggests that his strategic use of social media platforms may have played a significant role in shaping voter perceptions, particularly among younger demographics who dominate digital spaces (see

Table 6). Future research should explore the direct relationship between social media engagement and voter behavior to assess whether high online interaction translates into electoral success. Additionally, further studies could examine the role of artificial intelligence, algorithm-driven content distribution, and emerging digital tools in shaping modern political campaigns.