1. Introduction

Natural disasters are unpredictable, extraordinary events that destabilise the social structure by generating disorder, causing human losses and destruction.

The ‘Rapporto Città Clima 2023 Speciale Alluvioni’ by environment association Legambiente highlights the increase in floods and heavy rains in Italy, highlighting the fragility of the country in the face of the climate crisis and denouncing the cuts in resources for the prevention of hydrogeological instability (

ISPRA, 2023).

Many studies in Italy and elsewhere have repeatedly highlighted how the role of information, particularly local information, must be that of synthesising the various social and cultural policies proposed by public bodies and the correct representation of the condition of citizens’ lives in the area, going beyond national media logics, which are often based on speed and the spectacularisation of disasters (

Radcliffe & Wallace, 2021).

Local journalism can support cultural production and local heritage and also enhance the social and political participation of individual communities in their own language, respecting their traditions and conditions. Community media is not only limited to providing access to public space, but also to the intimate life of local communities (

Comunello & Mulargia, 2018). Despite the fact that local newsrooms, as well as all news agencies, now operate with reduced margins, forced to deal with changing news consumption habits and the shift from print to online news, which reduce the functioning of existing business models and the desirability of existing information products and services, it is in these situations of social and informational disorder that the centrality of territory-based journalism is revealed (

Radcliffe & Wallace, 2021).

Reporting from the local area means constructing a reasoned point of view and not a mere exposition of facts.

The local newspaper does not only collect news, but becomes a place of active intermediation, of aggregation. In this regard,

Hoak (

2021) prefers to speak of ‘geo-social’ news, content selected and hierarchised around the notions of relevance and place.

Information that speaks of and in the community, in fact, should seek to understand the plurality of components from which the social environment is made up and allow us to define interpretative outlooks through which to understand the world. Additionally, the local newspaper is a cultural expedient that provides the possibility of recognition; it becomes a meeting place.

The activity of a local newspaper is very much influenced by the place where it is located; it is important to understand whether there are more factories or more fields to cultivate, what work the inhabitants of the area do and what interests they have.

The lay of the land itself can make a huge difference, especially during a natural disaster.

News agencies alone can no longer do all the work of ‘whipping the news into shape’ and intervening by verifying its veracity, just as they cannot post dozens of up-to-date articles online and, at the same time, work with the pace of print media in the newsroom.

However, in this context of emergency coverage of natural disasters, it is visual media (images, videos), particularly local media, that document and convey the possible risk, impact and severity of a hazard. Problems arise when the images circulating, on a large scale and at high speed, are manipulated, false or come from an unrelated event or place.

These problematic images can have an impact on the way communities interpret the risk of an emergency. Furthermore, when visual media present information (e.g., a signal) that conflicts with what an emergency services agency is instructing the public to do, this can lead to uncertainty and confusion in the community on how to act (

Feldman & Hart, 2021).

Generally, media photo news, and even those collected for this research, are almost always problematic images that conflict with the emergency instructions to be taken during a natural disaster emergency, given the speed at which images are generated and the increasing expectations of agencies for real-time information on an event.

This is further exacerbated by conflicting views on who is responsible for verifying images disseminated during an event, despite fact-checking, source-checking, verification and denial being long-standing journalistic practices. News images and texts that focus on climate-oriented actions can increase hope and, in the case of texts, decrease fear and anger, and these effects generally hold across the ideological spectrum. In turn, the influence of emotions on policy support depends on ideology. Hope and fear increase support for climate policies for all ideological groups but particularly conservatives, whereas anger polarises the opinions of liberals and conservatives (

Feldman & Hart, 2021).

But what can be seen in the way disasters were covered by the local media in the pre-digital era? Which frames emerged and still emerge today?

3. Methodological Notes

The use of photo news in emergency and media contexts is not a recent novelty in the world of social research.

This practice returns to the interest of scholars and communication professionals when it finds ample space in the digital environment, on institutional sites first and on social channels more recently, but above all in the archives of the main mass media. In fact, photo news seems particularly suited to activating the response of its recipients and fostering their involvement (

Lovari & Righetti, 2020) as it is able to activate the engine of memory and emotions; at the same time, it is in this same environment that the risks of information overload are highest and most widespread. And it is in this aspect that photo news helps journalism and the public to ‘fix’ in both history and institutional practices those practices that are useful for planning interventions by anticipating future natural disasters (

Lee et al., 2020).

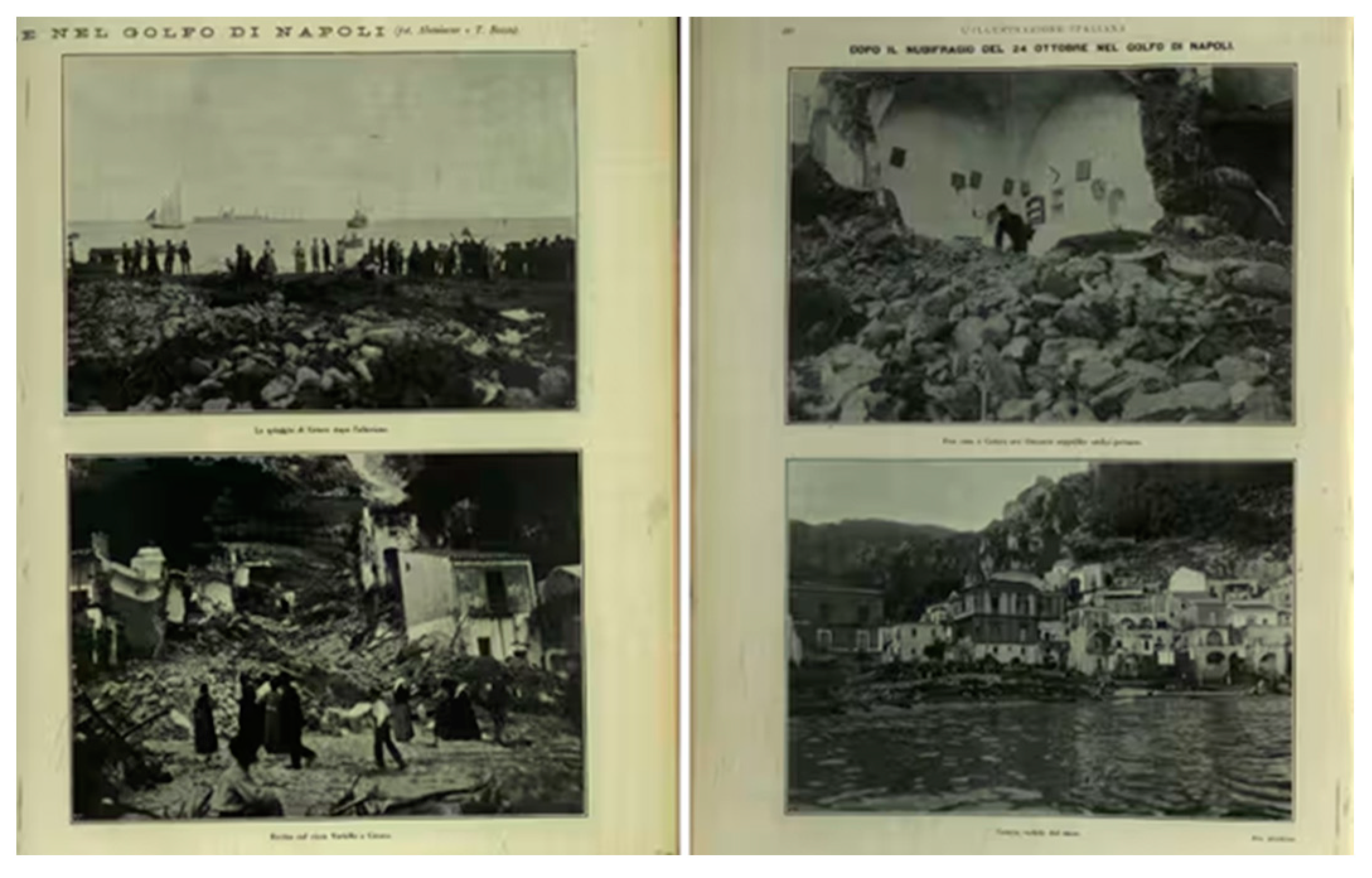

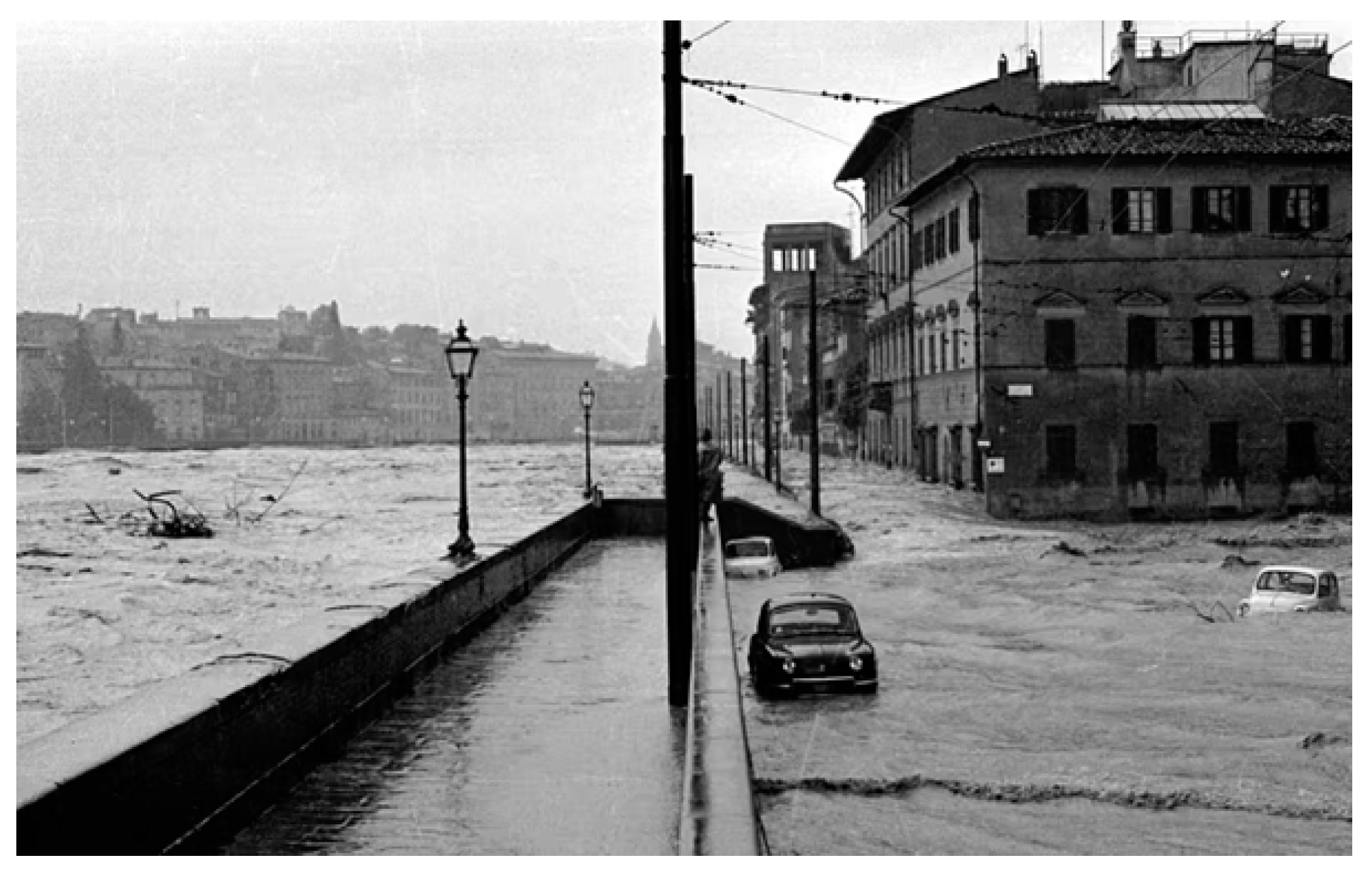

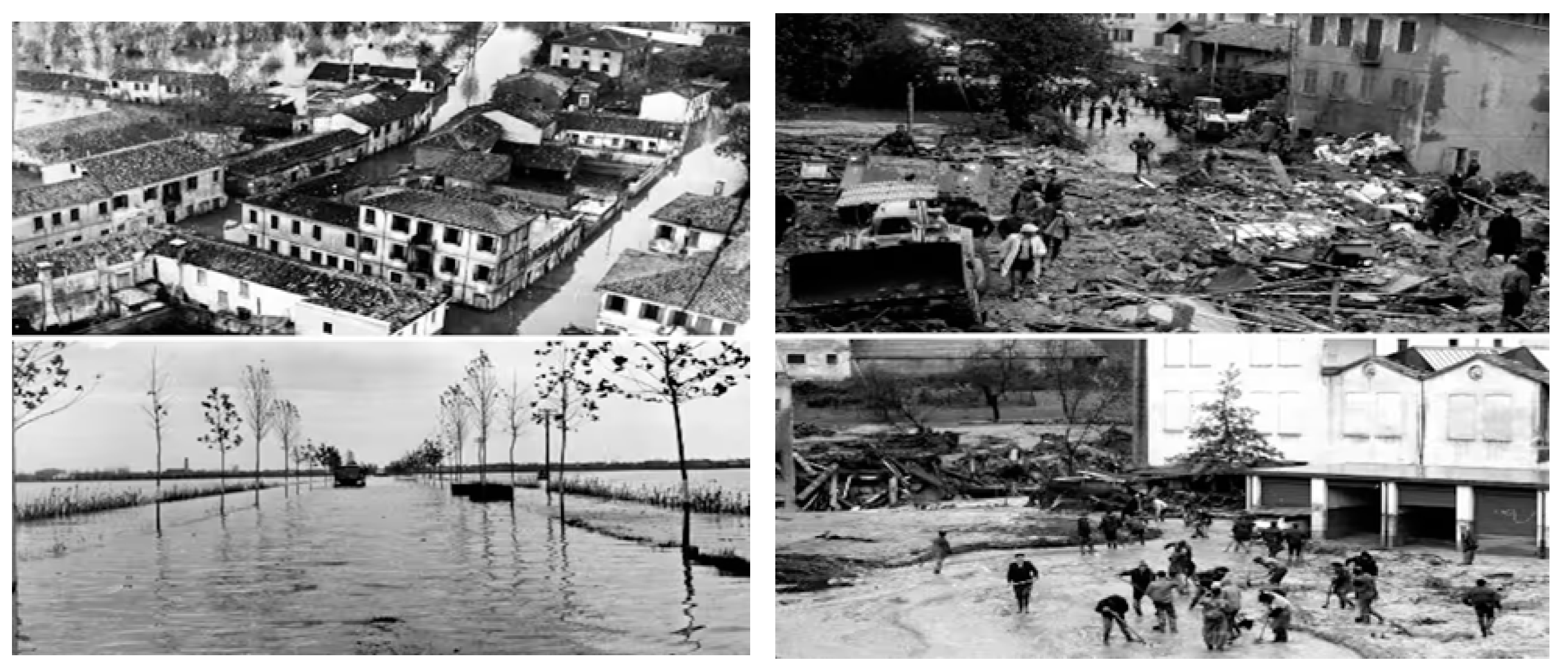

This is why numerous scholars on disaster journalism and crisis management dwell on the effectiveness and design of news because, while they facilitate and enable the understanding of a content, they also risk oversimplifying and trivialising the topics covered or pander to the risks of misinformation. But it is impossible, over time, to not consider their social-historical narrative value. The sociographic effort of this paper lies in trying to highlight common and different points of visual narratives of disasters between the Italian cases of the 20th century and the more recent ones of 2024 covered by the Italian local media. In this specific case, through a search in the main Italian media archives, images were collected, selected and analysed that have a historical documentary value for cities that were victims of disasters in specific historical periods. The photographs identified and the sociographic analysis proposed in the paper represent an attempt to reconstruct a social media memory of Italian disasters, based on official sources pre-selected by the same media, more or less recently, that decided to narrate them. The analysis of past and current disasters allows us to identify possible recurring frames, emerging journalistic logics and possible errors of spectacularisation.

The Importance of Sociography

This research is an exploratory journey into the issues of disaster journalism through a sociographic approach that involves the socio-historical categorisation and description of significant Italian disasters recounted by the local media using 10 archive images.

The approach used is that of the sociography of visual journalism. The idea of a ‘sociography’ of journalism first recalls the term ‘sociography’, a word coined by the Dutch sociologist Sebald Rudolf Steinmetz in 1913 (

Taekke, 2004).

By ‘sociography’, we mean a ‘free’ form of writing about society, social subdivisions and existing cultural patterns; in our specific case, we refer to the ‘transformative’ power of the media and journalistic work consisting of routines, interactions and relationships between individuals/groups involved in the production of news, together with organisations, institutions, structures, professional norms and values (

Taekke, 2004).

We speak, therefore, of a form of descriptive (scientific) narrative generally per-formed with the use of parameters and categories; in this case, both typical of sociological research and visual.

But it is not, in this case, simply a matter of describing phenomena and behaviour, but rather of incorporating visual data and social media theories into an applied study of the field of journalism and communication practices, going beyond the manualistic style of academic language.

The method lies in the telling of the social through images, not so much the media analysis of embedded photos.

In this sense, sociography thus offers spaces for new sensitivities, unresolved or incomplete topics and multiple, multidimensional and multiplying possibilities, in order to write and learn about the social in a different way that is also more accessible to the scientific public.

Groenman (

1948) argued that sociology tends to generalise, while sociography studies do so in particular. As an ‘individualising sociology’, sociography focuses on concrete situations, specific areas of relationships and groups.

In this article, the (social) narrative will mainly concern the photographic account of natural disasters in Italy by the media and journalists, with a critical interdisciplinary look between history and social prediction.

It is therefore not a question of analysing and obtaining research results from this collection. It is rather a matter of observing, tracing, identifying and fixing the frames, i.e., the recurring visual narrative patterns, typical of disaster journalism in Italy.

Three ‘media dimensions’ have been identified in this regard:

Ecological gaze: the transformation of natural and urban contexts;

Impotence: the force of nature against the technique of the individual;

Fine: the disaster that ‘kills’ public life, breaks the desire for collectivity and induces the death of the community, which after the disaster the latter of which can only be imagined (if not rebuilt).

5. Critical Considerations

News agencies alone can no longer do all the work of ‘whipping news into shape’ and intervening by verifying its veracity, just as they cannot post dozens of up-to-date articles online and, at the same time, work with the pace of print media in the newsroom (

Comunello & Mulargia, 2018).

The dynamic therefore imposed by the medium and the new digital environment makes it necessary in many cases to be essential, brief, dry and telegraphic (

Schudson, 2013). The consequence, as the interviewees themselves recognise, is the dissemination of fragments of information, produced in a wide variety of ways and distributed widely thanks to the reticular developments structured by platforms and algorithms.

The choice of format affects not only the quantity of news published, but also the identity of the individual local newspaper and the quality of its relationship with its audience.

A ‘historical’, ‘known’, ‘loyal’ and ‘close’ is an audience that buys and reads the news, as far as the printed local newspaper is concerned; an unfamiliar, varied and ‘distant’ audience, is one that uses the digital version of the same newspaper in an uncritical and inattentive manner, and comments on the piece without knowing the subject matter.

But in emergencies, there is a growing need for information to be available so that the inhabitants of the affected territories can better trace it. The broadcasting of news about a violent natural event is no longer a ‘simple reproduction’, but rather a representation with precise linguistic-narrative codes that meets the expectations of the public, which in turn, expresses the need for an interpretative key to extraordinary events, for which it is unable to account.

According to

Lombardi (

2006), when unexpected disasters occur, contemporary media have, on the one hand, the important function of updating the population in real time through digital channels and, on the other hand, the possibility of extending the narrative by communicating the data or details of the event through traditional media. This balancing act has to do with the organisational effectiveness of the local newsroom and the right choice of medium that journalists decide to use during the ‘life cycle’ of the disaster.

The selection and verification of news becomes increasingly difficult during the early stages of the emergency and the risk is to oscillate between uncontrolled overdoses of information and moments of information blackout. Moreover, after the first reports, newsrooms try to reconstitute roles and tasks, circumscribe and specify the extent of the event, monitor all communication channels and at the same time begin to contact the bodies—such as the civil protection, carabinieri, technical and scientific organisations—whose expertise may be affected, and then verify and report on them in the field.

At this point, photo news becomes a bridging medium that generates balance and reduces the risk of confusion and misinformation. Well-designed visual languages have the power to convey health messages clearly and effectively to non-experts, including journalists, patientsand politicians. Otherwise, they can confuse and alienate recipients, undermining the meaning of the message and leaving room for conflict, mistrust and pseudoscience.

6. Conclusions

In global emergencies, without economic aid in the long to medium term, the losses that community media suffer could have a profoundly negative impact on the information of (and for) the community. Without a vibrant local news industry, there is a risk that public institutions will act less responsibly and transparently in the exercise of their offices than they would in a situation of social stability (

Lombardi, 2006;

De Vincentiis, 2018).

Moreover, during a geographically small, or larger, emergency, there is hardly ever a general narrative of events. Instead, there is a myriad of narratives that need to be contextualised and explained to different communities.

And it is in these situations of social and informational disarray that the centrality of local journalism is revealed, as news agencies alone cannot do all the work of ‘shaping’ the news and intervening by verifying its veracity, just as they cannot post an article online and, at the same time, work with the times of the printed paper in the newsroom (

Greenberg & Scanlon, 2016).

The effort must be shared at local and national levels, integrating editorial and online work with field observation, in contact with the different communities of reference that are able to explain what is happening, thus integrating the journalist’s point of view. The goal is not only to investigate the consequences of a disaster, or to record the damage, but to collect and tell people’s moods and to extend a certain critical gaze on reality, which journalism should report on a daily basis.

And the photo news of yesterday and today, in this sense, can make a significant social, historical and cultural contribution.

Visual journalism encapsulates the narrative technique of “show, don’t tell”. Not only does it appear much more captivating than walls of text, but it also takes advantage of a serious cognitive advantage: humans are visual creatures and about half of our brain is involved in visual processing.

Good visual journalism can give the audience an immediate and profound impression, cutting through the weight of a convoluted story to reach the crux of the issue.

Although the world of news and media was the first to use the power of visual journalism, it did not take long for digital marketers to notice it and today visual journalism is used for brand marketing as well as for reporting. Whatever the real purpose of visual journalism, it is an excellent way to transform complex information into captivating, clear and accessible stories, respecting the victims and the contexts affected.

As partly mentioned, the role of visual information must be to synthesise the various social and cultural policies to deal with an emergency proposed by public bodies and the correct representation of the condition of citizens’ lives in the territory, going beyond the logic based on speed and the spectacularisation of disasters. As well highlighted by

Kovach and Rosenstiel (

2001), citizens have an “innate need” to know what happens beyond their direct experience, to be aware of events that involve them or that do not happen before their eyes.