Abstract

The phenomenon of disinformation raises serious questions for society, affecting public trust and democratic stability. In this context, an attempt is made to configure a profile of the practices of identification and fight against disinformation, assess the incidence of social networks, and identify citizens’ perceptions of media literacy in Ecuador. The methodology used is quantitative and qualitative, with a descriptive approach, using a survey, interviews with experts, and focus groups. The converging points between experts and citizens are the need to develop media literacy processes that begin in basic education and the institutionalisation of the fight against disinformation, which should be assumed through an articulation between citizens and schools. On the other hand, training to identify fake news is directly related to information verification practices. Likewise, statistical evidence shows that Ecuadorians who verify information perceive themselves as fully informed citizens.

1. Introduction

The media, both traditional and digital, are losing the trust of citizens, among other reasons, due to polarisation and clientelistic arrangements (Salazar 2022; Newman 2019), in addition to the phenomenon of the dissemination of false information (Osmundsen et al. 2021), disinformation, or fake news that is increasing on a daily basis.

Disinformation is information created and disseminated deliberately to cause harm, confuse, and falsify (Wardle and Derakhshan 2017). It corresponds to “a cultural phenomenon historically linked to the dynamics of mass media intervened by state and commercial interest groups” (Echeverría and Rodríguez 2023, p. 81). Disinformation involves false broadcasts, misinformation, rumours, conspiracy theories, bots, trolls, and fake news portals (Tucker et al. 2018).

Disinformation is intentionally fallacious (Jack 2017), denaturalises facts to mislead audiences (Fraguas de Pablo 2016; Rodríguez 2018; Sartori 2016), and multiplies thanks to the opacity of technological infrastructures and legal loopholes (Persily 2017), but fundamentally, it represents a risk for democracies because it requires states to ensure their institutions without restricting the freedoms and rights of citizens (Marcos et al. 2017; Pauner 2018; Walker 2018). For the European Union, disinformation is a latent threat to democracies (Bayer et al. 2019).

The presence and continuous increase of fake news question the credibility of contemporary journalism (Rodrigo-Alsina and Cerqueira 2019). Also, disinformation is an informative disorder that creates doubts and false debates and affects the economic profitability of the media (Del-Fresno-García 2019). Although the most delicate is that disinformation has contributed to generating patterns of reduced trust in the media that have become widespread to the point of fueling concerns regarding a “post-truth era” in which citizens shun made to replace them with those contents that, on the other hand, fit their emotions or political beliefs. (UNESCO 2021, p. 14)

The future of journalism depends, in large part, on how the media fights against disinformation (APM 2019). Unfortunately, the digital ecosystem does not yet have a concrete model to make the public interest and freedom of expression prevail in the face of the disinformation that is increasing daily (González 2022; Mihailidis and Viotty 2017).

Fake news spreads faster than real news on social media. The highest consumption of fake news occurs through social media, in contrast to traditional print media, where measurements indicate low consumption of misinformation (Koc-Michalska et al. 2020). However, many falsehoods are transmitted through social media, and the risk of dissemination is immediate (Vosoughi et al. 2018) because people multiply false news.

Links have been found between the “official” production of inaccurate information and the polarisation of voters (Pemstein et al. 2022), but it is worth remembering that this is a shared responsibility of the media and institutions (Marcos et al. 2017). Paradoxically, fake news dismantles the monopoly of institutional disinformation coming from the mainstream media in a bid to emancipate readers (Tanz 2017), evidencing the deficiencies of work strictly attached to deontology and civic values. In other words, those media and journalists who are not very solvent in the search for truth and the balance of sources act, even without intending it, as multipliers of hoaxes.

Disinformation explains the growing distrust towards media and politicians (Casero-Ripollés et al. 2023) and it would be a contradiction in terms that, at a time of transition to online data flows, there are people who trust traditional media more because they have better access to sources and more resources, compared to streamers or content creators (Alonso-Martín-Romo et al. 2023).

Disinformation affects attitudes towards democratic processes (Galarza 2022), appears on social networks, and influences journalists’ routines (Martín-García and Buitrago 2023; Montemayor and García 2021). The perception of misinformation by journalists and other professionals is explored, for example, in Rodríguez-Fernández and Establés (2023).

Research carried out in 26 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean revealed that misinformation and post-truth are widely disseminated in various media and that social media platforms play a relevant role in their transmission (Borrego-Ramírez et al. 2023). In Mexico, the relationship between the perception of false information and news consumption through platforms was studied during the Mexican federal elections of 2021 (De Elías and Muñiz 2022). This was scrutinised a year earlier, when the influence of social media on the perception of vote buying in Mexico was demonstrated (Gómez 2019).

Another study looked at preferences for digital ecosystems in Brazil, Colombia, and Spain. It was concluded that there is a tendency to access news through digital and audiovisual media and noted concerns about dubious sources and journalistic malpractice (Colussi et al. 2024). It is evident that social media platforms are modifying the communication landscape towards a state of disintermediation, which causes changes in communication patterns and norms (Barrios-Rubio 2024).

To counter disinformation, local and national actions are implemented in the so-called fight against disinformation, e.g., laws, media literacy, Internet blackouts, working groups, reports, and research (Funke 2021). There are also information verification and fact-checking initiatives that have an impact “on pluralism, as these organisations play a watchdog role in the post-truth era” (UNESCO 2019, p. 25). Among the highlighted experiences is the “Code of good practices against online disinformation” (Magallón-Rosa 2019). Although it is complex to establish a standard to regulate digital platforms that allow disinformation, three axes are identified: self-regulation, prevention in electoral campaigns, and defence of freedom of information and expression.

In Latin America, the effort to regulate platforms focused on establishing verification agencies, creating legislation to penalise fake news, and establishing dialogue with platforms to establish ethical standards (Rauls 2021). For its part, the European Union is defined as an axis of work raising awareness through citizens’ literacy to detect and counteract disinformation (European Commission 2018). These experiences allow us to point out that one of the most effective ways to reduce misinformation is to promote media and information literacy (MIL) to increase citizen participation (Wilson et al. 2011).

Regarding the above, there is an interest in studying people’s behaviour when faced with fake news and their ability to identify them, as has been done in other countries and communities (Cerdà-Navarro et al. 2021). Verifying information is vital and necessary to interpret the data and create critical participation based on ethical parameters. Moreover, because the role of social networks “in the dissemination of fake news must be analysed not only according to their objective capacity to distribute information, but also based on the fact that there are few limitations to these networks” (Cerdà-Navarro et al. 2021, p. 301).

Based on the above, research is proposed to (1) configure a profile of practices for identifying and combating disinformation. (2) to investigate the incidence of informed opinions and perceptions on the impact and possible alternatives for reducing disinformation. Finally, (3) to learn about citizens’ perceptions of media literacy and the institutional conditions needed to combat disinformation in Ecuador.

The case of Ecuador is considered because it is a country affected by violence, corruption, and a weak democracy generated, among other causes, by misinformation that impacts the exercise of freedom of expression (Mendoza et al. 2023; Sánchez et al. 2022; Sierra and Sola-Morales 2020; Vélez and Bello 2022), and also because 76% of the population has access to the Internet and can participate in public opinion through social media platforms. These users generate more than 16.3 million connections, showing access from more than one device per user. TikTok consolidates as one of the main social networks, with close to 12 million accounts. While Facebook and Instagram integrate 15.7 million accounts—users (Del Alcazar Ponce 2023), i.e., there is a digital ecosystem prone to news consumption through social networks, with the foreseeable risk of receiving fake news.

A study conducted in Azuay (Ecuador) analysed how journalists covered medical and scientific information during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed that journalists had limitations in the selection of sources and lacked knowledge about medical and scientific topics (Verdugo and Rodríguez-Hidalgo 2024). However, scientific information about Ecuadorians’ knowledge and practices on how to combat misinformation is still scarce.

Ecuador’s legal framework considers guarantees for freedom of expression and the subsequent responsibilities of the media and journalists in cases of disinformation. To promote adequate treatment of information and generation of content, current regulations are considered, where limits and possible violations are established, the current regulations are considered, where limits and possible violations are established. Article 66, number 18 of the 2008 Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador, recognises the right to honour and good name, and number 19 establishes the right to the protection of personal data, which includes access to and decision on information and data of this nature. The collection, filing, processing, distribution, or dissemination of such data or information shall require the authorisation of the owner or the mandate of the law, and number 20, recognises the right to personal and family privacy.

On the other hand, the “Ley Orgánica de Comunicación” (Organic Law of Communication) of 2022 includes preponderant articles for journalistic action, as follows: “Article. Subsequent liability”, “Art. 20.—Subsequent liability of the media”, “Article. 21.—Civil liability”, and in particular Article. 22.—Right to receive quality information.—All people have the right to have the information of public relevance that they receive through the media verified, contrasted, accurate, and contextualised. Verification involves verifying that the events reported have actually occurred. Contrasting involves collecting and publishing, in a balanced way, the versions of the persons involved in the events narrated, unless any of them has refused to provide their version, which shall be expressly recorded in the journalistic note. (Asamblea Nacional 2022)

2. Methodology

The methodology used is quantitative and qualitative, with an exploratory and descriptive approach, using a survey, expert interviews, and focus groups. The research instruments complement each other and together contribute to the fulfilment of the research objectives. Through the survey, the profile of practices and the fight against misinformation is established (objective 1). The expert interviews contribute to investigating the incidence of informed opinions and perceptions on the impact and possible alternatives to reduce misinformation (objective 2). In addition, the focus groups derive evidence to know the perceptions of citizens on media literacy and institutional conditions (objective 3).

A questionnaire based on two studies was used.

- (a)

- A survey of digital users on information habits was applied in Argentina by the organisation “100 per cent”, made up of three organisations linked to journalism. This work sought to find out the level of disinformation among Argentines and how it impacts on their daily lives. It was directed by Mosto et al. (2020).

- (b)

- The research by Cerdà-Navarro et al. (2021) entitled “Fake or not fake, that is the question: recognition of disinformation among university students”, investigated the ability of university students to discern the veracity of the information they receive.

The questionnaire was made up of five blocks: (1) identification of fake news; (2) frequency of news consultation; (3) frequency of participation in forums and news comments; (4) prevalence of fake news and identification skills; and (5) sociodemographic questions. The application was made via a Google form between 23 May 2022 and 31 January 2023. It received 263 participants, corresponding to 112 men and 151 women. The average age is 26 years, by age group: 18–27 years: 74%; 28–37 years: 19%; 38–47 years: 5%; 48–57 years: 2%. The participants live in different cities in Ecuador and have different occupations. Data processing was carried out with the support of SPSS software, version 23.

Also, six semi-structured interviews with experts were conducted in November 2023 via email. The profiles of the experts correspond to three male and three female academics, specialists in digital communication, journalism, and public opinion, working in Latin American universities.

Finally, three online focus groups were conducted between 28 June and 20 July 2022, due to mobility restrictions to avoid contagion from COVID-19 and to cover participants from several cities. Twenty-five people took part, of whom 10 are men and 15 are women. The average age is 40 years old. According to the professional profile, they correspond to 10 primary and secondary school teachers, seven journalists, three professionals in civil engineering and industry, two business administrators, two doctors, and one person working in an ONG.

From a theoretical perspective, a focus group is an interactive practice of social research (Callejo 2001; Galeno 2004), “consisting of bringing together a group of six to ten people and provoking a discussion among them on the topic of interest, which must be led by a moderator” (López 2010, p. 150); it is “ideal for capturing dominant representations, values, affective formations, and imaginaries, allows for the reconstruction of social meanings, and reproduces a given macro-social situation on a given scale” (Pedraz et al. 2014).

A discussion group allows the expression of different positions and attitudes of the participants, the exchange of information, and the orientation of the discourse on the reality to be investigated (Canales and Peinado 1995). On the other hand, “conducting discussion groups online is logistically feasible. Social researchers currently have a series of technological and communicative resources that we can manage and configure to shape group dynamics” (Parada 2012, p. 112).

The research questions have four axes and consider the following issues: (a) Media literacy: what does it mean to be media literate? How should social media support media and information literacy? (b) Sources: which social actor generates the most disinformation, and which information source generates trust? (c) Social media platforms: is fake news spread through the media or is it a phenomenon linked to social media? (d) Practices in the fight against disinformation: what predominant practices do Ecuadorians have? What do verification companies contribute to the purging of news? What institutional conditions are needed?

3. Results

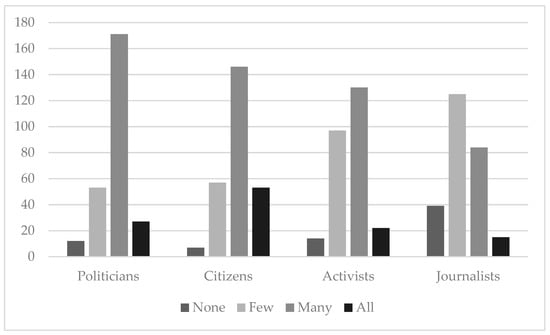

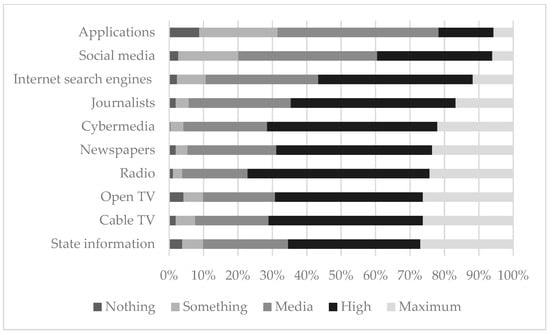

The representations of the data are in the following graphs and tables, which show that there is greater trust in journalists than in politicians. Figure 1 shows the perceptions of the respondents, who indicate that a lot of fake news would be generated by political leaders and citizens. However, according to Figure 2, the values of trust and credibility of the media, be it cyber media, radio, newspapers, or television, as institutions that provide reliable stories and data, are restored.

Figure 1.

Perception of Fake News authorship.

Figure 2.

Trustworthy information providers.

Regarding news consumption, respondents indicate that they mostly follow the news every day, especially national news, and therefore perceive themselves as highly or fully informed (Table 1). The consumption of news through social networks occurs above all on Instagram and WhatsApp, supported by images and short texts, leaving less space for argumentation, leaving interpretations to the subjectivities and referential frameworks of each person, and leaving room for speculation with the few data and inputs that are transmitted through social networks.

Table 1.

News consumption practices.

The practices against disinformation carried out by Ecuadorians are in Table 2. Associations between information verification and three variables stand out: identification of fake news, importance of training to identify fake news, and self-perception. Chi-square tests were conducted to test the aforementioned associations among the 263 participants.

Table 2.

Practices against disinformation.

Among the variables “verify information” and “identify fake news”, the observed Chi square value was 51.8 with eight degrees of freedom, and the associated p-value was <0.001, indicating a statistically significant association.

Between these variables ‘verify information’ and ‘importance of training’ the observed Chi-square value was 29.3 with four degrees of freedom, and the associated p-value was <0.001, indicating a statistically significant association.

Between the variables “verify information” and “informed person”, the observed Chi square value was 75.7 with six degrees of freedom, and the associated p-value was <0.001, indicating a statistically significant association.

Interpretation of these results suggests that, based on respondents’ perceptions, people who verify information are more likely to identify fake news, value training to combat misinformation, and perceive themselves as fully informed citizens. It is important to note that this analysis has some limitations, including the possibility of selection bias and the lack of control for other potential risk factors. The results of the Chi-square test allow us to assert that there is a significant association between information verification practices and training in identifying fake news, underscoring the importance of media and information literacy interventions.

As a result of the interviews, the following testimonies were obtained. “Fake news is linked to social networks, it originated in them, but it expanded to traditional media” (Interviewee-1). “They are linked to the digital society, instant messaging services and platforms. In the current media ecosystem, the clickbait culture makes its harmful effects more powerful and amplified” (Interviewee-2). Traditional channels “disseminate less fake news and its impact is lower, however, the online press through clickbait generates a large volume of fake news. In social networks, it is observed that fake news is integrated into disinformation strategies” (Interviewee-3).

According to experts, citizens have criteria to detect fake news (Interviewee-4), “they are more alert” (Interviewee-1), but “there are deficiencies in terms of the lack of media literacy, which generates a feeling of general distrust with the content that is consumed through the Internet” (Interviewee-2).“It is necessary to teach users with basic information detection guidelines such as reverse navigation, variety of sources, etc., but also to value the role of verifiers and get users used to going to them” (Interviewee-3).

Social media platforms could prevent the spread of fake news. “There are some attempts to stop misinformation on social media, but given the volume of lies and the difficulties in identifying them, the effort has to be shared between social media and education” (Interviewee-1). In addition to the legal obligations imposed by national and international legal frameworks, platforms “have the moral obligation to neutralize fake news as soon as they detect it. They are also affected by an overload of content, many generated by the audience themselves, which makes the detection and elimination process difficult” (Interviewee-5).

Among the intervention alternatives are “implementing rules against the publication of false or harmful content, and establishing measures against those who do not respect them. Transparency in political advertising, the promotion of reliable sources” (Interviewee-6), Additionally, “through transparency in the algorithms used, use of alternative recommendation and search where veracity and diversity of sources are a priority. Integration of verifiers in decision-making by platform moderators” (Interviewee-3). Or directly, through “warning and awareness campaigns” (Interviewee-5).

On the other hand, the groups fighting against disinformation contribute to the purging of news. “They are an extraordinary contribution. They do a fairly rigorous verification; they dismantle the lie clearly by providing evidence. But it is a function that all media must assume. It should be a fundamental section of any media” (Interviewee-1). “Fact-checking platforms are a pillar in the fight against disinformation, with their rigorous work they manage to dismantle that false news that have been most shared or are viral” (Interviewee-6). They are effective instruments to stop disinformation and give citizens tools to identify disinformation (Interviewee-4).

Unfortunately, citizens are unaware of the existence of the verifiers and therefore do not turn to them when they have doubts about the news. I believe that the work they do is positive and should continue. However, they cannot cope with the information overload and effectively combat the spread of fake news. Their work is very useful because it allows us to understand the narratives of action for those who seek to destabilise a democracy in a disinformative way (Interviewee-5).

Sometimes, verification initiatives generate mistrust “due to ideological biases or partisan motivations, despite the efforts of organisations to demonstrate their impartiality” (Interviewee-2), but it is evident that “they carry out a complementary task to information professionals. Ideally, they should have some kind of accreditation that guarantees their transparency and rigour, and they should be integrated in both the production and verification of content” (Interviewee-3); therefore, it is urgent to support these organisations “through funding and guaranteeing independent support” (Interviewee-4).

The experts were consulted on how to teach media skills to deal with misinformation. In the answers, they point out: “I believe that the best way to combat misinformation is to provide quality information, and that requires culture, information and values. Of the ethics of communication, which is the defense of democracy” (Interviewee-5). “More media literacy actions are needed for all segments of society to understand what mechanisms are available to them to distinguish fake news. Therefore, it is important to implement media education in schools” (Interviewee-6).

In higher education, there are “initiatives such as conferences or workshops where verifiers and journalists have taught students how to identify fake news, raising awareness so that they do not contribute to its dissemination” (Interviewee-3). “In communication faculties, students are made aware of the importance of the rigorous practice of journalism, where the verification of sources is especially relevant” (Interviewee-6).

The interviews reveal patterns in the responses. A recurring theme is the connection between fake news and social media, with several interviewees highlighting that fake news is born and spread through these platforms, empowered by the strategy of misinformation. Traditional media seem to have less impact on the spread of fake news, but the online press amplifies this problem considerably. The need for media literacy is another crucial point: although citizens are more alert, there are still significant shortcomings that generate widespread distrust of online content.

Another notable pattern is the importance of collaboration between social media platforms and education in curbing misinformation. Interviewees agree that platforms have both a legal and moral obligation to neutralise fake news but face difficulties due to the volume and overload of user-generated content. In addition, the need for clear rules against publishing fake content and the promotion of trusted sources is underlined. Transparency in algorithms and the integration of verifiers in platform decision-making are seen as effective strategies to combat misinformation.

Additionally, the crucial role of verifiers and fact-checking organisations is highlighted. Although these initiatives are essential and contribute significantly to the fight against misinformation, they still face challenges such as public distrust due to possible ideological biases. Interviewees suggest that these organisations should receive independent funding and accreditation that guarantees their transparency and rigour. Media education, from schools to higher education, is seen as a fundamental solution to empower citizens to detect and prevent misinformation by promoting rigorous and ethical journalistic practice.

In the discussion groups, the answers about what it means to be literate with respect to the media are “access to knowledge” (Participant-01), “search for information” (Participant-02, Participant-03, Participant-04), “form public opinion objectively” (Participant-04).

Other participants pointed out that media literacy is “broad knowledge and skills to analyse information” (Participant-05). “Knowledge and communicating in an ethical way” (Participant-06). “Knowledge of national and international events, to have a criterion, a voice and a sense in terms of information so that we are not manipulated” (Participant-09). “Investigative and critical capacity” (Participant-08) to “maximise the advantages and minimise the damage in the new informational, digital and communicational landscapes. This will allow people to interact in a critical and effective way” (Participant-07); it is also valued as “training to give more information to people, through television and radio” (Participant-10).

Media literacy involves “differentiating which news are false and true” (Participant-11), “discriminate the publications with yellowing headlines that do not have a reliable research process that allows you to guarantee their content” (Participant-02), contrast “before sharing or talking about them” (Participant-12), “Contrast in different sources being analytical being analytical of the context in which they have been published” (Participant-13).

Being mediatically literate means possessing “critical thinking” (Participant-14) and “critical sense, but we need to improve access to education” (Participant-15), to be “active producers of information, innovative and creative, who make good use of the different media available to us to express ourselves”. (Participant-16).

Other interventions in discussion groups point out that media literacy is “to avoid digital illiteracy” (Participant-17), “avoid being subject to criminal activities or manipulation” (Participant-18), and, particularly, “interaction and interpretation of information presented in society” (Participant-19), to “contribute to improve structures and social fabrics” (Participant-20).

The focus groups indicated that the mass media can support media and informational literacy through “fulfilling a robust, active and independent role, acting in favor of the general interest” (Participant-07), which is achieved with the “dissemination of quality information” (Participant-13). “Radio and television programs that train people” (Participant-10). The higher purpose is to seek democracy and to frame ourselves in the right of international freedom of expression; to be as plural as possible, that all voices are integrated in the contexts of information, the more plural and democratic we are in the information process, we will be filling these gaps. We must seek democracy, to give citizens what they deserve to receive” (Participant-15).

In a similar context, it was noted that the media must “use an approach that includes the family promoting cooperation” (Participant-21), in other words, “doing good journalism and plurality “ (Participant-22), “Promoting teaching and ethics, with a language that can reach everyone” (Participant-11). “In short, serve the community” (Participant-13). The media “are the window for citizens to make decisions, be critical and participants” (Particpant-09).

In their responses to what institutional conditions are needed to promote verification and avoid misinformation, citizens point out that “national policies are required to carry out media and informational literacy with children in schools, colleges and universities (Participant-06), “because these are directed and normal in the scope of application and its inclusion in the educational system” (Participant-07). “We need a society that improves its education process to be empowered it in its right to access information” (Participant-15).

However, “the problem is not that the laws exist, it is that they are in line with the times and that the government gives them the importance they deserve” (Participant-14). “Rather, policies are required from the education system. The most vulnerable populations are minors, who are much more exposed than adults to false content” (Participant-18), and should “include spaces for teaching and guidance from childhood through educational establishments, protected by law. It is essential to create a criterion that allows them to be alert to identify real information and stay away from malicious content” (Participant-02), “implement media literacy programs from the first levels of the education system, because communication is present from an early age in living beings” (Participant-22).

The government “lacks a comprehensive programme where the media can help to make the population media and information literate” (Participant-20). “It is extremely necessary that these policies are implemented to ensure that the growth of fake news is stopped and that media manipulation becomes less and less in our society” (Participant-13), so that “students learn to be critical and counteract information” (Participant-16).

Testimonies from the focus groups show key points. Participants agree that being media literate implies having access to and the skills to seek and analyse information critically and objectively. This knowledge ranges from understanding national and international events to being able to differentiate between real and fake news and avoid being manipulated. It also highlights the need to improve media education from an early age and at all educational levels so that citizens develop critical thinking and can interact effectively in the digital environment.

Another relevant coincidence is the perception that the mass media have a crucial role to play in supporting media literacy. Participants suggest that the media should play an active and independent role in disseminating quality information and promoting plurality and democracy. Furthermore, it emphasises the importance of national and educational policies that regulate the inclusion of media literacy in the education system. This would help the younger generation to be better prepared to deal with misinformation and to use the different media available in an ethical and critical way. The need for comprehensive programmes and adequate laws is fundamental to empowering society in its right to access information and to counteract media manipulation.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The points of convergence between experts and citizens are the need to develop media literacy processes from basic education and the institutionalisation of the fight against disinformation, which should be assumed through an articulation of efforts between citizens and schools (Amorós-García 2018; Elías and Catalán-Matamoros 2020). The relevance of early interventions has been evaluated, and it was found that media literacy initiatives executed in schools and communities are effective in raising awareness about the negative impacts of misinformation (Jeong et al. 2012).

On the foundations laid in basic education, better discernment would be achieved in relations between citizens; the final purpose is to build plural public spaces for reaching agreements and, implicitly, to build identity and tolerance (Papacharissi 2008).

If, on the one hand, ‘formal education has to deepen knowledge that allows the development of an educated citizenry capable of identifying and dismantling disinformation strategies’ (Calvo et al. 2020, p. 115), it is also true that alternatives, new pedagogies, and teaching models must be explored to highlight the importance of involving the new generations in understanding and reducing disinformation.

Previous studies have evidenced that playful methods help young people and adults to recognise and counteract fake news (Roozenbeek and van der Linden 2019), thus taking advantage of the massification of online games where participants are motivated and build skills to advance their understanding of a target to defeat or conquer, in this case lies, misleading constructs, and incorrect news.

Ecuadorians’ ratings of information consumption on social networks are shown in Table 1. The platforms with the highest consumption are Facebook and WhatsApp. The time dedicated to social networks is between one and three hours per day.

Based on the statistical verification presented in the results, informational literacy (training to identify false news) has a direct relationship with information verification practices; it is almost a “sine qua non” condition to improve media consumption. Finally, statistical verification of citizens’ perceptions gives way to the claim that Ecuadorians who verify information are able to identify fake news, value training to fight disinformation, and perceive themselves as fully informed citizens.

There remain commitments from the media to continue, based on deontological practices, with quality coverage and news broadcasts as one of the antidotes against misinformation, thus recovering the trust of citizens and advocating for solid democracies in a future where they envision new models of sustainability supported by the protagonism of people, their environments, and greater transparency. This conclusion is supported by the testimonies in the focus groups, for example, by mentioning that the mass media could support media literacy.

Quantitative results show a profile of citizens’ practices and habits in relation to disinformation, while qualitative data from interviews and focus groups reveal in-depth insights into the impact of disinformation and strategies to combat it.

The evidence presented in this research confirms that the practices of some media and digital platforms play a role in the spread of fake news. Combating disinformation is a contemporary and urgent issue that requires a balance between the promotion of human rights and freedom of expression. A fact that is a priority for nations, when at the beginning of 2024 the World Economic Forum pointed out that disinformation and extreme weather events are two of the most important risks for that year (World Economic Forum 2024). Thus, the urgency of evaluating whether, despite regulations, society is facing a process of new forms of censorship remains (Magallón-Rosa 2023).

Participants pointed out that the clickbait culture and the lack of effective regulation contribute to the spread of misinformation. They highlighted the need to develop new pedagogies and educational models that integrate media literacy from an early age, using interactive and technological methods to engage young people. Empowering people with media literacy skills and promoting responsible use of social media is vital to counteracting the spread of false information.

Expert interviews revealed that, in addition to educational interventions, a robust legal framework that supports media literacy and regulates the quality of information disseminated by the media is essential. The experts agreed that national policies should include media literacy as a priority, ensuring that both educational institutions and the media work together to improve the critical capacity of citizens. The creation of comprehensive media literacy programmes in schools is seen as a key strategy to empower future generations in the face of misinformation.

The research highlights the importance of implementing national policies to combat disinformation in Ecuador. The results show that a combination of innovative educational methods and an appropriate legal framework can significantly improve citizens’ ability to identify and counter fake news.

This study has limitations present in the survey and interviews. Thus, the quantitative method chosen includes a few respondents, and the sample is not representative of the Ecuadorian population; that is, there are risks when generalising or extrapolating to the population. Expert interviews do not consider the diversity of participants; the opinions of experts from other parties involved in the fight against disinformation, such as journalists, fact-checkers, policymakers, representatives of regulatory bodies, etc., are not included to obtain a more complete vision. New research will be required with statistically calculated samples and include other expert profiles to explain the phenomenon of misinformation. The approaches to this work, as mentioned, are exploratory and descriptive.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally and proportionally to the conceptualisation, methodological design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, writing, revising, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research on Human Beings of the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (CEISH399 UTPL), dated 16 September 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alonso-Martín-Romo, Luis, Miguel Oliveros-Mediavilla, and Enrique Vaquerizo-Domínguez. 2023. Perception and opinion of the Ukrainian population regarding information manipulation: A field study on disinformation in the Ukrainian war. Profesional de la Información 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós-García, Marc. 2018. Fake News. La verdad de las noticias falsas [Fake News. The Truth about Fake News]. Barcelona: Plataforma Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- APM. 2019. Informe anual de la profesión periodística [Annual Report on the Journalistic Profesión]. Madrid: Asociación de prensa de Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- Asamblea Nacional. 2022. Ley orgánica reformatoria de la ley orgánica de comunicación (390359) [Organic Law Reforming the Organic Law on Communication (390359)]. Quito: Comisión de Relaciones Internacionales y Movilidad Humana. Available online: https://www.asambleanacional.gob.ec/es/multimedios-legislativos/64742-ley-organica-reformatoria-de-la-ley (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Barrios-Rubio, Andrés. 2024. El gobierno desde X: Análisis del caso Gustavo Petro en Colombia [Government from X: Analysis of the Gustavo Petro case in Colombia]. Index Comunicación 14: 255–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, Judit, Natalija Bitiukova, Petra Bárd, Judit Szakács, Alberto Alemanno, and Erik Uszkiewic. 2019. Disinformation and Propaganda—Impact on the Functioning of the Rule of Law in the EU and Its Member States. Brussels: European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Borrego-Ramírez, Nali, Marcia Leticia Ruiz-Cansino, and Daniel Desiderio Borrego-Gómez. 2023. La posverdad en América Latina y el Caribe: Una perspectiva netnográfica de la agnogénesis [Post-truth in Latin America and the Caribbean: A netnographic perspective on agnogenesis]. Revista CienciaUAT 18: 158–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callejo, Javier. 2001. El grupo de discusión: Introducción a una práctica de investigación [The Focus Group: Introduction to a Research Practice]. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, Dafne, Lorena Cano-Orón, and Almudena Esteban Abengozar. 2020. Materiales y evaluación del nivel de alfabetización para el reconocimiento de bots sociales en contextos de desinformación política [Materials and literacy assessment for the recognition of social bots in contexts of political disinformation]. Icono 14 18: 111–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, Manuel, and Anselmo Peinado. 1995. Grupos de discusión. In Métodos y técnicas cualitativas de investigación en ciencias sociales [Qualitative Social Science Research Methods and Techniques]. Edited by José Manuel Delgado and Juan Gutiérrez Fernández. Madrid: Síntesis, pp. 288–311. [Google Scholar]

- Casero-Ripollés, Andreu, Hugo Doménech-Fabregat, and Laura Alonso-Muñoz. 2023. Percepciones de la ciudadanía española ante la desinformación en tiempos de la COVID-19: Efectos y mecanismos de lucha contra las noticias falsas [Spanish Citizens’ Perceptions of Disinformation in Times of COVID-19: Effects and Mechanisms to Fight Fake News]. Revista ICONO 14 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà-Navarro, Antoni, David Abril-Hervás, Bartomeu Mut-Amengual, and Rubén Comas-Forgas. 2021. Fake o no fake, esa es la cuestión: Reconocimiento de la desinformación entre alumnado universitario [Fake or Not Fake, That Is the Question: Recognition of Misinformation among University Students]. Revista Prisma Social 34: 298–320. [Google Scholar]

- Colussi, Juliana, Paula de Souza Paes, Rainer Rubira-García, and Thays Assunção Reis. 2024. Perceptions of University Students in Communication about Disinformation: An Exploratory Analysis in Brazil, Colombia and Spain. Observatorio (OBS*) 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Elías, Jessie, and Carlos Muñiz. 2022. Impacto del consumo de información en medios sociales sobre la percepción de desinformación en el contexto electoral mexicano de 2021 [Impact of social media information consumption on the perception of disinformation in the 2021 Mexican electoral context]. ALCEU (Rio de Janeiro) 22: 126–44. [Google Scholar]

- Del Alcazar Ponce, Juan Pablo. 2023. Ecuador estado digital junio 2023 [Ecuador Digital State June 2023]. Pichincha: Mentinno Consultores. [Google Scholar]

- Del-Fresno-García, Miguel. 2019. Desórdenes informativos: Sobreexpuestos e infrainformados en la era de la posverdad [Information disorder: Overexposed and underinformed in the post-truth era]. El Profesional De La Información 28: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, Martín, and César Augusto Rodríguez. 2023. ¿La alfabetización digital activa la incredulidad en noticias falsas? Eficacia de las actitudes y estrategias contra la desinformación en México [Does digital literacy activate disbelief in fake news? Effectiveness of attitudes and strategies against disinformation in Mexico]. Revista De Comunicación 22: 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elías, Carlos, and Daniel Catalán-Matamoros. 2020. Coronavirus en España: El miedo a las noticias falsas ‘oficiales’ impulsa WhatsApp y fuentes alternativas [Coronavirus in Spain: Fear of ‘official’ fake news drives WhatsApp and alternative sources]. Medios y Comunicación 8: 462–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2018. Action Plan against Disinformation. EEAS. European External Action Service. Brussels: European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Fraguas de Pablo, María. 2016. La desinformación en la sociedad actual [Disinformation in today’s society]. Cuadernos.Info. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, Daniel. 2021. Global Responses to Misinformation and Populism. In The Routledge Companion to Media Disinformation and Populism. Edited by Howard Tumber and Silvio Waisbord. London: Routledge, pp. 449–58. [Google Scholar]

- Galarza, Rocio. 2022. Impacto de la desafección política de la ciudadanía en México [The impact of political disaffection of citizens in Mexico]. Sphera Publica 1: 56–80. [Google Scholar]

- Galeno, María Eumelia. 2004. Estrategias de investigación social cualitativa: El giro en la mirada [Qualitative Social Research Strategies: The Turn in the Gaze], 1st ed. La Carreta: Medellín. [Google Scholar]

- González, Rosa María. 2022. Ciudadanía y alfabetización digital en tiempos de desinformación—Desafíos más allá de la pandemia [Citizenship and Digital Literacy in Times of Disinformation—Challenges beyond the Pandemic]. Felipe Chibás and Sebastián Novomisky. Navegando en la Infodemnia con AMI. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, Ricardo R. 2019. Impacto de las redes sociales en la percepción ciudadana sobre la compra del voto en México [The impact of social networks on citizens’ perception of vote buying in Mexico]. Revista Mexicana De Opinión Pública 1: 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, Caroline. 2017. Lexicon of Lies. Data & Society Research Institute. Available online: https://datasociety.net/library/lexicon-of-lies/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Jeong, Se-Hoon, Hyunyi Cho, and Yoori Hwang. 2012. Media Literacy Interventions: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Communication 62: 454–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koc-Michalska, Karolina, Bruce Bimber, Daniel Gomez, Matthew Jenkins, and Shelley Boulianne. 2020. Public Beliefs about Falsehoods in News. International Journal of Press/Politics 25: 447–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Inmaculada. 2010. El grupo de discusión como estrategia metodológica de investigación: Aplicación a un caso [The focus group discussion as a methodological research strategy: Application to a case study]. Edetania 38: 147–56. [Google Scholar]

- Magallón-Rosa, Raúl. 2019. La (no) regulación de la desinformación en la Unión Europea. Una perspectiva comparada [The (non-)regulation of disinformation in the European Union. A comparative perspective]. Revista De Derecho Político 1: 319–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallón-Rosa, Raúl. 2023. Desinformación y democracia [Disinformation and Democracy]. Telos. Available online: https://telos.fundaciontelefonica.com/desinformacion-y-democracia/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Marcos, Juan Carlos, Juan Miguel Sánchez, and María Olivera. 2017. La enorme mentira y la gran verdad de la información en tiempos de la postverdad [The big lie and the big truth of information in the post-truth era]. Scire 23: 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-García, Alberto, and Álex Buitrago. 2023. Professional perception of the journalistic sector about the effect of disinformation and fake news in the media ecosystem. ICONO 14 Revista De Comunicación y Tecnologías Emergentes 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Marina, Mariano Dagatti, and Paulo Carlos López. 2023. Fake news y desinformación: Desafíos para las democracias de América Latina y el Caribe [Fake news and disinformation: Challenges for Latin American and Caribbean democracies]. Cuadernos Del Centro De Estudios De Diseño y Comunicación 26: 173–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mihailidis, Paul, and Samantha Viotty. 2017. Spreadable Spectacle in Digital Culture: Civic Expression, Fake News, and the Role of Media Literacies in “Post-Fact” Society. American Behavioral Scientist 61: 441–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemayor, Nancy, and Antonio García. 2021. Percepción de los periodistas sobre la desinformación y las rutinas profesionales en la era digital [Journalists’ perceptions of misinformation and professional routines in the digital age]. Revista General De Información y Documentación 31: 601–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosto, Cecilia, Francisco Corrallini, and Ariel Mosto. 2020. ¿Cómo se Informan los Argentinos? FOPEA y Thomson Media. Available online: https://fopea.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/FOPEA-Guias-Como-se-informan-los-argentinos.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Newman, Nic. 2019. Resumen ejecutivo y hallazgos clave del informe de 2019. Informe de noticias digitales [Executive Summary and Key Findings from the 2019 Report]. Oxford: Digital News Report. [Google Scholar]

- Osmundsen, Mathias, Alexander Bor, Peter Bjerregaard Vahlstrup, Anja Bechmann, and Michael Petersen. 2021. Partisan polarization is the primary psychological motivation behind political fake news sharing on Twitter. American Political Science Review 115: 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharissi, Zizi. 2008. The Virtual Sphere 2.0: The Internet, the Public Sphere, and Beyond. In Routledge Handbook of Internet Politics. Edited by Andrew Chadwick and Philip N. Howard. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, pp. 230–45. [Google Scholar]

- Parada, Francisco. 2012. Premisas y experiencias: Análisis de la ejecución de los grupos de discusión online [Premises and experiences: Analysis of the implementation of online focus groups]. Encrucijadas 4: 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Pauner, Cristina. 2018. Noticias falsas y libertad de expresión e información: El control de los contenidos informativos en la red [Fake news and freedom of expression and information: The control of news content on the web]. Teoría y Realidad Constitucional 41: 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedraz, Azucena, Juan Zarco, Milagros Ramasco, and Ana María Palmar. 2014. Investigación cualitativa [Qualitative Research], 1st ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Pemstein, Daniel, Kyle L. Marquardt, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Juraj Medzihorsky, Joshua Krusell, Farhad Miri, and Johannes von Römer. 2022. The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-National and Cross-Temporal Expert-Coded Data. In V-Dem Working Paper, 7th ed. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, Varieties of Democracy Institute, No. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Persily, Nathaniel. 2017. Can Democracy Survive the Internet? Journal of Democracy 28: 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauls, Leonie. 2021. How Latin American Governments Are Fighting Fake News. New York: Americas Quaterly. Available online: https://americasquarterly.org/article/how-latin-american-governments-are-fighting-fake-news (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Rodrigo-Alsina, Miquel, and Laerte Cerqueira. 2019. Periodismo, ética y posverdad [Journalism, ethics and post-truth]. Cuadernos.Info 44: 225–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Roberto. 2018. Fundamentos del concepto de desinformación como práctica manipuladora de la comunicación política y las relaciones internacionales [Basics of the concept of disinformation as a manipulative practice in political communication and international relations]. Historia y Comunicación Social 23: 231–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, Leticia, and María José Establés. 2023. Impacto de la desinformación en las relaciones públicas: Aproximación a la percepción de los profesionales [The impact of misinformation on public relations: An approach to practitioners’ perceptions]. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico 29: 843–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozenbeek, Jon, and Sander van der Linden. 2019. Fake news game confers psychological resistance against online misinformation. Palgrave Commun 5: 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, Grisel. 2022. Más allá de la violencia: Alianzas y resistencias de la prensa local mexicana [Beyond Violence: Alliances and Resistance in Mexico’s Local Press. Ciudad de México: CIDE. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Agustín Alexander, Sabrina Candela, and Ángel Torres-Toukoumidis. 2022. Desinformación y migración venezolana. El caso Ecuador [Disinformation and Venezuelan migration. The case of Ecuador]. Cuadernos Del Centro De Estudios De Diseño Y Comunicación 26: 107–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, Giovanni. 2016. Homo videns. La sociedad teledirigida [Homo Videns. The Remote-Controlled Society]. Barcelona: Debolsillo. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, Francisco, and Salomé Sola-Morales. 2020. Golpes mediáticos y desinformación en la era digital. La guerra irregular en América Latina [Media coups and disinformation in the digital age. Irregular warfare in Latin America]. Comunicación Y Sociedad 17: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanz, Jason. 2017. El periodismo lucha por la supervivencia en la era posterior a la verdad [Journalism Struggles for Survival in Post-Truth Era]. Wired. Available online: www.wired.com/2017/02/journalism-fights-survival-post-truth-era/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Tucker, Joshua A., Andrew Guess, Pablo Barberá, Cristian Vaccari, Alexandra Siegel, Sergey Sanovich, Denis Stuka, and Brendan Nyhan, eds. 2018. Social Media, Political Polarization, and Political Disinformation: A Review of the Scientific Literature. Menlo Park: Hewlett Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2019. Tendencias mundiales en libertad de expresión y desarrollo de los medios: Informe Regional 2017–18 América Latina y el Caribe [Global Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Report 2017–18]. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2021. Aspectos destacados de “el periodismo es un bien común: Tendencias mundiales en libertad de expresión y desarrollo de los medios. Informe mundial 2021/2022” [Highlights from “Journalism is a Common Good: Global Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development. World Report 2021/2022”]. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez, Gabriela Lourdes, and Juliana Mayte Bello. 2022. Participación del fact-checking para combatir la desinformación: Caso Ecuador Verifica [Engaging fact-checking to combat disinformation: The Ecuador Verifica Case]. ComHumanitas: Revista Científica De Comunicación 13: 92–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo, Édison, and Claudia Rodríguez-Hidalgo. 2024. Periodistas y desinformación sobre COVID-19 desde el punto de vista médico-científico. Estudio de caso en Azuay, Ecuador [Journalists and misinformation about COVID-19 from a medical-scientific point of view. Case study in Azuay, Ecuador]. Contratexto 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi, Soroush, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral. 2018. The spread of true and false news online. Science 359: 1146–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Christopher. 2018. What is sharp power? Journal of Democracy 29: 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. Information Disorder. Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Carolyn, Alton Grizzle, Ramon Tauzon, Kwame Akyempong, and Chi Kim Cheung. 2011. Media and Information Literacy Curriculum for Teachers. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. 2024. Global Risks 2024: Disinformation Tops Global Risks 2024 as Environmental Threats Intensify. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/press/2024/01/global-risks-report-2024-press-release/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).