Abstract

This study presents a systematic review of the scholarly literature on Russia–Ukraine Propaganda on Social Media over the last ten years. This study performs a bibliometric analysis of articles published in the last ten years (2012–2022) and acquired from the Scopus database, followed by a brief content analysis of top articles from leading sources. Furthermore, the study aims to find gaps in the literature and identify the research area that could be developed in this context. VOSviewer application was used for data mining and data visualization from Microsoft Excel. Some interesting facts were found in the bibliometric analysis regarding research and other perspectives. Though the study was related to the propaganda of Russia and Ukraine, the USA is identified as the most attentive country in terms of research and publication on the topic. On the other hand, Russia published many articles regarding its own propaganda on social media.

1. Introduction

Social media refers to the processes by which individuals generate, share, and/or exchange information and ideas within virtual communities and networks. This interactive media technology promotes the creation and dissemination of information, ideas, and other forms of expression (Kietzmann et al. 2011; Obar and Wildman 2015). Nowadays, a large number of people are connected via social media, with 4.8 billion people, to be exact, in 2021 (Dean 2021). Life has become easier because of social media as it has become a medium of interaction with friends and families, sharing opinions and expressions, receiving information, posting media, doing business, and so on (Cleveland et al. 2023; Khaola et al. 2022). Yet, social media has become a double-edged sword as it also exacerbates divisions, helps spread conspiracy theories, allows people to exist in ‘echo chambers’, etc. (D’souza et al. 2021). Media houses, independent media, and other sources of information are now exceedingly active in social media to spread real-time news. There has been huge competition in spreading the news as fast as possible to reach more users. For those who have the privilege of an internet connection, almost every sector is connected to social media. Not only certified media houses or agencies but also government officials and every sector of the internet-privileged world exist in different types of social media to spread information. Here comes the real challenge. Information is not in some specific organizations/agencies’ hands. Anyone can share any information on social media within a second, whether it is verified or not. The considerable amount of unverified information creates misinformation or false information, which diverts the actual purpose of information (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017; Jabeen et al. 2023; Kim 2023; M. Wu and Pei 2022).

False information can be categorized based on its intent. Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people, often with political motives, and is a form of propaganda. Misinformation, on the other hand, is false information spread without harmful intent (Bertolami 2022; Hasan 2023; Petratos 2021). Both disinformation and misinformation exist in the current world’s social media. Social media is saturated with misinformation and disinformation. The use and availability are uneven though. Some countries in the world even specialize in it. Academics have recently paid great attention to the massive spread of disinformation through social media. Social media has facilitated the rapid dissemination of rumors and false information to a large audience (Wu et al. 2019).

Besides social media disinformation, Russia and Ukraine are significant parts of the geopolitical politics of the world. Russia and Ukraine were part of the USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) before Russia changed its political and economic systems—Ukraine became independent in the 1990s. Russia and Ukraine have a close history related to their borders, economics, culture, and family ties (Masters 2022). The intention between Russia and Ukraine is central to world politics as there have been few conflicts between those countries in this 21st century. The biggest one was the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine, where Russia annexed the Crimea peninsula of Ukraine in 2014. Since Russia’s invasion began on 24 February 2022, the deadliest war in Europe since World War II is going on between these two countries.

The Kremlin’s propaganda has a huge historical background to shape people’s views. There has been a war that is already known as a social media war or the first TikTok war; the terms disinformation, propaganda, and misinformation on social media are being discussed everywhere (Liñán 2010; Scriver 2015), and there has been huge manipulation of information in social media by both parties. As modern research focuses on social media fake news or disinformation (Shu and Liu 2019), there is a lot of research related to propaganda on social media, with multiple studies focusing on the Russia and Ukraine context. This study aims to identify existing literature on Russia–Ukraine Propaganda on Social Media, analyze its origins, and find gaps for future research.

2. Methods and Materials

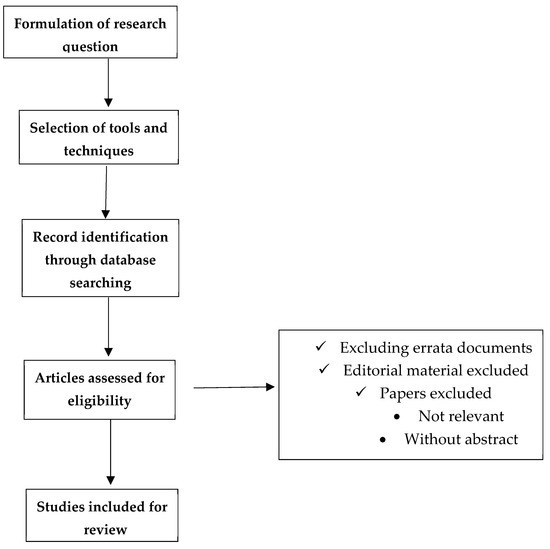

This systematic review adhered to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) 2020 guidelines, and has been registered in the SSRN database (Page et al. 2021). This study systematically reviews the scholarly literature on Russia–Ukraine propaganda on social media. It identifies and describes the connection between Russian and Ukrainian propaganda appearing on social media. A systematic literature review is a scientific procedure that identifies gaps in the relevant literature and develops a potential research topic by identifying themes, trends, and weak points (Wright et al. 2007). Figure 1 also represents the data found in the Scopus database related to the research titled as PRISMA flow chart.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow chart, Source: Author.

All fundamental descriptions with details of the data used in this research are delineated in Table 1. The study comprised 456 documents published from January 2012 to October 2022. The author analyzed the research related to Russia–Ukraine and Social Media Propaganda over the last 10 years. Among them, a vast majority (83.33%) are articles and academic conference papers, which are accordingly 56.8% and 26.53%. The remaining 16.67% of documents are book chapters (12.06%) and review papers (3.07%). There are a limited number of letters and editorials (see Table 2). A total of 758 authors make a scientific contribution to Russia–Ukraine-related propaganda appearing on social media. To be more precise, of those 456 documents, 211 documents are single authored. Of the remaining multi-authored documents, 547 authors have contributed. The average citations that are used per document are relatively high, at 185.30.

Table 1.

Description and distribution of primary information.

Table 2.

Information about document type and numbers.

Figure 2 depicts the sample selection procedures used in this study in detail. This study gathered data from 512 documents in the Scopus database in Excel format. This study included publications from January 2012 to October 2022. The keywords used in Scopus searches were “Russia Ukraine”, “Propaganda”, and “Social Media”. Only materials produced in the English language were included in the analysis (journals, articles, books, conference papers, letters, reports, reviews, and notes). VOSviewer software version 1.6.18 (www.vosviewer.com, accessed on 10 November 2022) was used for bibliometric analysis. VOSviewer is a tool for designing and visualizing bibliometric networks. These networks, which may include journals, researchers, or individual articles, can be constructed based on citation, bibliographic coupling, co-citation, or co-authorship links. VOSviewer also has text mining tools for creating and visualizing co-occurrence networks of key phrases collected from the scientific literature (VOSviewer 2022). Thematic analysis was performed using MS Excel. A manual selection of topics in the VOSviewer was used to generate network and density visualizations for the purpose of analyzing a variety of data characteristics.

Figure 2.

Sample selection process, Source: Author.

Later in this study, these types of bibliometric analysis were performed:

- Co-occurrence of keywords;

- Most highly cited sources, authors, and documents;

- Bibliographic coupling.

In the next section, the study shows the results and discussion of that analysis. In the last part, the study concludes with the future research prospects and limitations of this study.

2.1. Bibliometric Findings

The research assessed the co-occurrence of all keywords used in the literature on Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media. In this study, the most frequently cited sources, authors, and documents were examined. In addition, bibliographic coupling was used to identify common sources between articles. In the following section, bibliometric findings are presented.

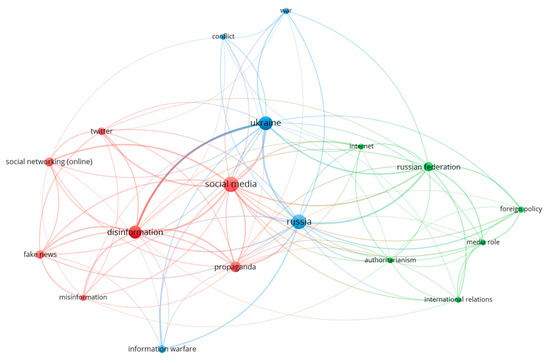

2.2. Co-Occurrence of Keywords

Because the topic of Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media literature is diverse, there are 1376 keywords that have been engaged frequently throughout the literature. The study screened the keywords by assigning a minimum frequency of ten occurrences per key term, and 18 of 1376 met the criteria. The size of the nodes in Table 3 and Figure 3 represents the frequency of the keyword.

Table 3.

Frequency and link strength of keywords.

Figure 3.

Co-occurrence network diagram of all keywords. Source: Author.

However, the data suggests that “Social Media” was the most commonly used phrase of the 71 keywords. Other randomly used words comprise “Russia (68 Keywords)”, “Ukraine (52 Keywords)”, “Disinformation (44 Keywords)”, “Propaganda (36 Keywords)”, “Russian Federation (28 Keywords)”, “Social Networking (24 Keywords)”, “Fake News (23 Keywords)”, “Information Warfare (19 Keywords)”, “Twitter (17 Keywords)”, “Foreign Policy (13 Keywords)”, “Misinformation (12 Keywords)”, “War (12 Keywords)”, “Media Role (10 Keywords)”, “Internet (10 Keywords)”, “Authoritarianism (10 Keywords)”, “Internet Relations (10 Keywords)”, and “Conflict (10 Keywords).” The findings also suggested that the most crucial correlation was found between the phrases “Social Media” and “Disinformation.”

Additionally, “Social Media” was discovered to be closely related to “Russia”, “Ukraine”, “Disinformation”, and “Propaganda.” These data indicate that in the Russia–Ukraine conflict, misinformation, propaganda, and fake news through social media are the top concern as they are closely interconnected.

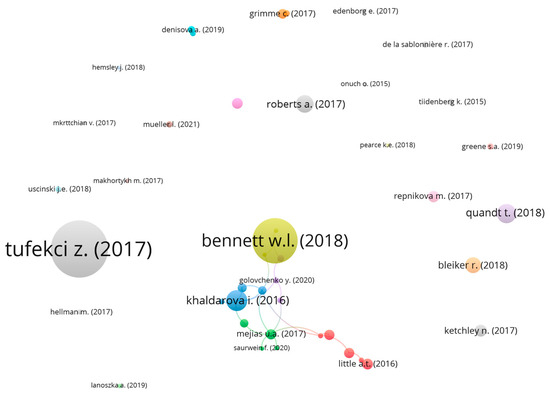

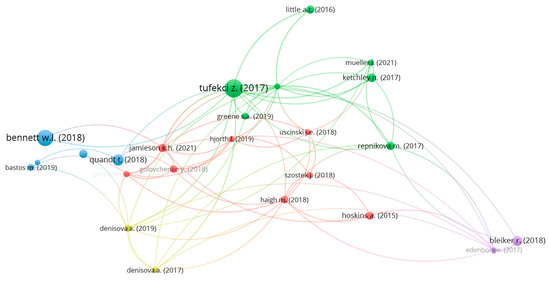

2.3. Most Influential Documents

In order to determine the most frequently cited publications in this field, the analysis was limited to publications cited at least 25 times in Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media. A total of 36 of the 456 documents fulfill the criteria Table 4 lists the 24 most cited publications in Russia, Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media literature. Figure 4 depicts the network map based on the most frequently cited publications.

Table 4.

Most frequently cited documents on Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media. Source: Author.

Figure 4.

Network map of the highest cited documents on Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media. Source: Author.

The study found that the publication Tufekci (2017) is the most cited document; however, it is not connected to all the publications, as shown in Figure 4. Similarly, (Quandt 2018), (Bleiker 2018), (Ketchley 2017), (Repnikova 2017), (Roberts 2017), and (Grimme et al. 2017) are also missing in the associated set, despite being among the 24 most cited studies.

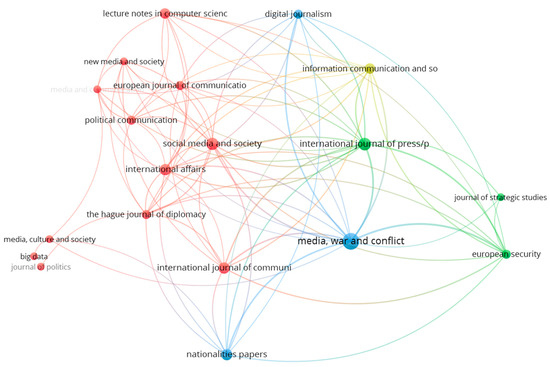

2.4. Most Influential Sources

This section discusses the most frequently cited sources in the Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media literature, as well as the number of publications that use them. The analysis used two documents and twenty-five citations as the minimum number of documents and citations for a source, respectively, to sort the data. After filtering, only 19 of the 314 sources met the threshold. Table 5 provides an overview of the essential and impactful sources. In the analysis of Propaganda and Social Media regarding the Russia-Ukraine conflict, certain sources are cited more frequently than others, illustrating key nodes of influence and dissemination (see Figure 5).

Table 5.

Most cited sources and documents. Source: Author.

Figure 5.

Network map of the most frequently cited sources on Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media. Source: Author.

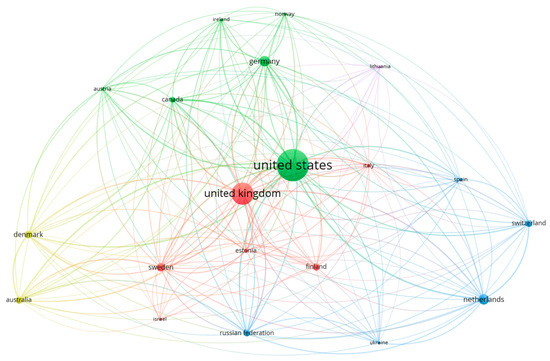

2.5. Most Documented Countries on Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda and Social Media Literature

It has been determined that the United States is the country most frequently mentioned in the literature on Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media, with 128 references to the United States (see Table 6). The United Kingdom and Russian Federation are in second and third places with 74 and 33 documents, respectively. However, Germany, Sweden, and Australia are the other three nations that have produced more than 20 documents. On the other hand, Ukraine has 17 documents. Figure 6 depicts a density representation of the most documented countries in relation to Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media.

Table 6.

Countries with the corresponding number of documents.

Figure 6.

Density visualization of mostly documented countries. Source: Author.

2.6. Bibliographic Document Coupling

Bibliographic coupling findings, according to the designers of VOSviewer, demonstrate the overlap of references between publications. The greater the relationship between two works, the greater the number of common references. In this study, the analysis was filtered by specifying a minimum of 25 document citations, obtaining 36 papers. However, only 77 documents were found to be related to the large sample. Figure 7 depicts the bibliographic coupling of documents in the Russia–Ukraine, Propaganda, and Social Media categories.

Figure 7.

Network visualization of bibliographic coupling of documents. Source: Author.

3. Discussion

The discussion chapter of this bibliometric analysis on Russia–Ukraine Propaganda via Social Media delves into the complexities uncovered by the study, highlighting pronounced global engagement, particularly from the United States. This interest transcends academic circles, reflecting the wider international implications and the strategic significance of information warfare in contemporary geopolitics. The convergence of themes around disinformation and the dual role of social media—as both a facilitator and battleground for propaganda—aligns with existing literature, suggesting an evolving academic focus towards the dynamics of digital influence and statecraft.

Our analysis identifies a foundational corpus of scholarly works that have significantly shaped discourse on digital propaganda, marking an intellectual trajectory towards understanding the complexities of information manipulation in the digital age. Key texts such as Tufekci (2017), Bennett and Livingston (2018), and Khaldarova and Pantti (2016) have been pivotal in defining the contours of this discourse. Tufekci’s work on the power and fragility of networked protest highlights how social media platforms can be both a tool for grassroots mobilization and a conduit for misinformation. Bennett and Livingston discuss the broader implications of the disinformation order on democratic institutions, while Khaldarova and Pantti provide insights into the narrative battles over the Ukrainian conflict.

The implications of these findings extend beyond academia, offering pivotal insights for policymakers and social media platforms grappling with the proliferation of misinformation. For instance, the integration of computational propaganda into the analysis underscores the role of digital tools and autonomous agents in shaping public opinion. Bolsover and Howard (2017), Woolley and Howard (2016), and Benkler et al. (2018) discuss how big data and computational propaganda are utilized in political communication, providing a critical lens through which to view the manipulation of information in the digital age. Audience participation in spreading propaganda through reposting and sharing is another critical aspect. Hyzen (2023) and Wanless and Berk (2020) explore how participatory propaganda amplifies the reach of disinformation, emphasizing the role of audiences in the propagation of false information. This highlights the importance of understanding the mechanisms of information dissemination and the active role played by users in the digital ecosystem.

Integrating our study within the broader spectrum of related research highlights a shared concern over foreign influence operations and their implications for democratic societies. The active participation of the United States in researching and countering misinformation campaigns underscores a broader, policy-driven engagement with state-led information warfare. This aligns with scholarly and policy efforts to scrutinize and mitigate Russia’s strategic use of social media for propaganda purposes within its geopolitical pursuits—an endeavor that has garnered increasing attention and action in Western nations.

The thematic focus on disinformation, fake news, and strategic social media use by Russia and Ukraine is parallel to investigations into the broader impacts of digital misinformation on public opinion, electoral integrity, and international diplomacy. These studies underscore the need for enhanced digital literacy, regulatory interventions, and global cooperation to counteract the adverse effects of online propaganda. Furthermore, the call for more empirical research into the efficacy of propaganda and its countermeasures reflects a growing academic dialogue aiming to dissect not only the dissemination and content of misinformation but also its psychological and societal repercussions. This suggests a move towards a multidisciplinary approach, integrating insights from communications, psychology, political science, and information technology to address the complex nature of digital disinformation.

4. Conclusions

With half of the world’s population having access to the internet and social media (Kemp 2022), concerns around misinformation and disinformation on these platforms are escalating. Social media has become a potent medium for disseminating disinformation and propaganda at a low cost. Government officials, individuals, interest groups, and organizations have seized this opportunity to spread misleading information to manipulate public opinion. Russia and Ukraine are notable examples of this trend, engaging in significant state-sponsored propaganda campaigns. This study reveals that, despite the specific focus on Russia and Ukraine, the issue commands global attention due to the considerable geopolitical history and implications these nations hold for the rest of the world. The pressing need for an informed and multifaceted response to this contemporary challenge is evident, underscoring the importance of continued scholarly attention and strategic policy-making to safeguard the integrity of public discourse in the face of evolving technological and geopolitical landscapes.

Limitations and Future Research Prospects

This review identifies a significant gap in empirical research concerning the role of propaganda on social media in the context of Russia and Ukraine. Through this study, the author has refined the methodology for determining the study’s focus, presenting it as an initial exploration into a complex area that warrants further investigation. The author plans to extend research through a content analysis that will delve into more detailed research areas within this sector. In particular, the forthcoming content analysis will highlight the nature of the content published in these studies and identify potential research gaps.

However, the current study is not without its limitations. One of the primary constraints is the reliance on the Scopus database for document collection. Future research could benefit from incorporating data from the Web of Science and other databases to broaden the scope and depth of the analysis. Additionally, the selection of keywords such as “Russia Ukraine”, “Social Media”, and “Propaganda” was strategic for this study, yet it omitted other pertinent terms like “Misinformation”, “Disinformation”, “Fake news”, “Kremlin Propaganda”, and “Ukraine Russia”. Future researchers are encouraged to consider these and other relevant keywords to enrich the investigation of propaganda on social media. This expanded approach will facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the research landscape and contribute to the body of knowledge on social media propaganda.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Allcott, Hunt, and Matthew Gentzkow. 2017. Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives 31: 211–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, Marco, and Johan Farkas. 2019. “Donald Trump Is My President!”: The Internet Research Agency Propaganda Machine. Social Media and Society 5: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkler, Yochai, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts. 2018. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Steven Livingston. 2018. The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication 33: 122–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolami, Charles. 2022. Misinformation? Disinformation? Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 80: 1455–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiker, Roland. 2018. Visual global politics. In Visual Global Politics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsover, Gillian, and Philip Howard. 2017. Computational propaganda and political big data: Moving toward a more critical research agenda. Big Data 5: 273–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, Mark, Rajesh Iyer, and Barry J. Babin. 2023. Social media usage, materialism and psychological well-being among immigrant consumers. Journal of Business Research 155: 113419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’souza, Felecia, Sita Shah, Olukayode Oki, Lydia Scrivens, and Jonathan Guckian. 2021. Social media: Medical education’s double-edged sword. Future Healthcare Journal 8: e307–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Sablonnière, Roxane. 2017. Toward a psychology of social change: A typology of social change. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, Brian. 2021. How Many People Use Social Media in 2022? (65+ Statistics). Backlinko, October 10. Available online: https://backlinko.com/social-media-users#social-media-usage-stats (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Denisova, Anastasia. 2019. Internet memes and society: Social, cultural, and political contexts. In Internet Memes and Society: Social, Cultural, and Political Contexts. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovchenko, Yevgeniy, Mareike Hartmann, and Rebecca Adler-Nissen. 2018. State, media and civil society in the information warfare over Ukraine: Citizen curators of digital disinformation. International Affairs 94: 975–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Samuel A., and Graeme B. Robertson. 2019. Putin v. the People: The Perilous Politics of a Divided Russia. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 1–287. [Google Scholar]

- Grimme, Christian, Dennis Assenmacher, and Lena Adam. 2018. Changing Perspectives: Is It Sufficient to Detect Social Bots? In Social Computing and Social Media. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 10913 LNCS. Cham: Springer, pp. 445–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, Christian, Mike Preuss, Lena Adam, and Heike Trautmann. 2017. Social Bots: Human-Like by Means of Human Control? Big Data 5: 279–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, Maria, Thomas Haigh, and Nadine I. Kozak. 2018. Stopping Fake News: The work practices of peer-to-peer counter propaganda. Journalism Studies 19: 2062–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Mahedi. 2023. Journalistic Resistance to Russian Authoritarian Disinformation: The Case of Media Dissidents in the Russia-Ukraine Wars of 2014 & 2022. Master’s thesis, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, Andrew, and Ben O’Loughlin. 2015. Arrested war: The third phase of mediatization. Information Communication and Society 18: 1320–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyzen, Aaron. 2023. Propaganda and the Web 3.0: Truth and ideology in the digital age. Nordic Journal of Media Studies 5: 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, Fauzia, Anushree Tandon, Nasreen Azad, A. K. M. Najmul Islam, and Vijay Pereira. 2023. The dark side of social media platforms: A situation-organism-behaviour-consequence approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 186: 122104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, Kathleen Hall. 2021. Cyberwar: How Russian Hackers and Trolls Helped Elect a President: What We Don’t, Can’t, and Do Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Simon. 2022. More Than Half of the People on Earth Now Use Social Media—DataReportal—Global Digital Insights. Dataportal. July 21. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/more-than-half-the-world-now-uses-social-media (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Ketchley, Neil. 2017. Egypt in a Time of Revolution: Contentious Politics and the Arab Spring. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldarova, Irina, and Mervi Pantti. 2016. Fake News: The narrative battle over the Ukrainian conflict. Journalism Practice 10: 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaola, Peter P., Douglas Musiiwa, and Patient Rambe. 2022. The influence of social media usage and student citizenship behaviour on academic performance. The International Journal of Management Education 20: 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, Jan H., Kristopher Hermkens, Ian P. McCarthy, and Bruno S. Silvestre. 2011. Social Media? Get Serious! Understanding the Functional Building Blocks of Social Media. Business Horizons 54: 241–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Su Jung. 2023. The role of social media news usage and platforms in civic and political engagement: Focusing on types of usage and platforms. Computers in Human Behavior 138: 107475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragh, Martin, and Sebastian Åsberg. 2017. Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: The Swedish case. Journal of Strategic Studies 40: 773–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, Miguel Vázquez. 2010. History as a propaganda tool in Putin’s Russia. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 43: 167–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Andrew T. 2016. Communication technology and protest. Journal of Politics 78: 152–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, Jonathan. 2022. Ukraine: Conflict at the Crossroads of Europe and Russia | Council on Foreign Relations. Council of Foreign Relations. October 11. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/ukraine-conflict-crossroads-europe-and-russia#chapter-title-0-4 (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Mejias, Ulises A., and Nikolai E. Vokuev. 2017. Disinformation and the media: The case of Russia and Ukraine. Media, Culture and Society 39: 1027–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, Lisa. 2021. Political Protest in Contemporary Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obar, Jonatham A., and Steve Wildman. 2015. Social Media Definition and the Governance Challenge: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Telecommunications Policy 39: 745–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petratos, Pythagoras N. 2021. Misinformation, disinformation, and fake news: Cyber risks to business. Business Horizons 64: 763–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, Thorsten. 2018. Dark participation. Media and Communication 6: 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repnikova, Maria. 2017. Media Politics in China: Improvising Power under Authoritarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Anthea. 2017. Is International Law International? Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–406. [Google Scholar]

- Scriver, Stacey. 2015. War Propaganda. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Kai, and Huan Liu. 2019. Detecting Fake News on Social Media. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukal, Denis, Sergey Sanovich, Richard Bonneau, and Joshua A. Tucker. 2017. Detecting Bots on Russian Political Twitter. Big Data 5: 310–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiidenberg, Kartin. 2015. Odes to heteronormativity: Presentations of femininity in Russian-speaking pregnant women’s Instagram accounts. International Journal of Communication 9: 1746–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tufekci, Zeynep. 2017. Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 1–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VOSviewer. 2022. VOSviewer—Visualizing Scientific Landscapes. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/ (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Wanless, Alicia, and Michael Berk. 2020. The audience is the amplifier: Participatory propaganda. In The SAGE Handbook of Propaganda. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd., pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, Samuel C., and Philip N. Howard. 2016. Political Communication, Computational Propaganda, and Autonomous Agents: Introduction. International Journal of Communication 10: 4882–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Rick W., Richard A. Brand, Warren Dunn, and Kurt P. Spindler. 2007. How to write a systematic review. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 455: 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Liang, Fred Morstatter, Kathleen M. Carley, and Huan Liu. 2019. Misinformation in Social Media. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter 21: 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Manli, and Yiming Pei. 2022. Linking social media overload to health misinformation dissemination: An investigation of the underlying mechanisms. Telematics and Informatics Reports 8: 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).