Discovering the Radio and Music Preferences of Generation Z: An Empirical Greek Case from and through the Internet

Abstract

1. Introduction

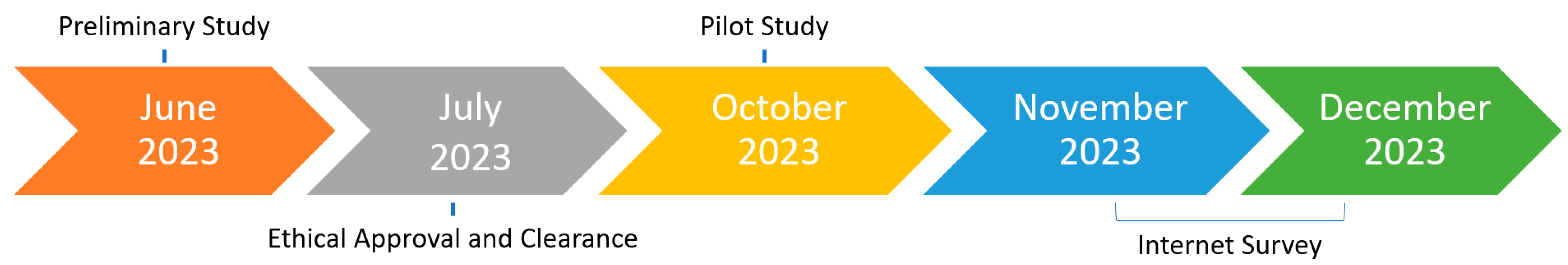

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Web-Based Questionnaire: The Measuring Instrument

2.2. Pilot Study

- The first phase served as a pre-test, where the selected participating sample answered the web-based questionnaire in printed form in the presence of the main researcher/principal investigator, in order for the participants to provide any feedback or comments. Notably, a total of 18 GenZ’s students with different origins (i.e., Cyprus, Greece, Russia, and Bulgaria) were randomly selected from KES College in Cyprus. The specific students attended the fall semester of the academic year 2023–2024 in the Greek course in “Principles of Public Relations” of the Office Administration and Secretarial Studies program of the School of Business and Administration Studies or the Greek course in “Principles of Marketing” of the Medical Representatives Management program of the School of Health Studies or the Greek courses in “Public Relations Campaigns” and “Crisis Management and Public Relations” of the Journalism with Public Relations program of the School of Journalism and Media Studies. Additionally, the particular participant sample is characterized as a convenience sample (see Kontogiannatou 2018, p. 104), while its size is considered acceptable in the context of a pre-test (i.e., 5 to 100 participants) (Carpenter 2018, pp. 33–34);

- The second phase served as expert feedback and was in the form of an online focus group. Specifically, nine adults from Greece with backgrounds in humanities, mass media, and audiovisual industry, who had again participated in previous pilot studies of the research project MACE, were conscripted to participate (Nicolaou et al. 2022). Obviously, the specific sample is also characterized as a convenience sample (see Kontogiannatou 2018, p. 104). This specific phase, due to the methodological approach applied, could also be considered a pre-test (Carpenter 2018, pp. 33–34) or a kind of pre-pilot test, because the participants also answered the web-based questionnaire at the end of online focus group, giving comments and observations; and finally

- The third and final phase served as a pilot test, involving four Greek graduate postgraduate students of the SJMC and members of GenZ. Participants are also designated as a convenience sample (see Kontogiannatou 2018, p. 104), and their task was to participate in a rehearsal of the Internet survey in real field conditions, in order to estimate the time required to complete the web-based questionnaire.

2.3. Research Data Collection, Processing, and Analysis

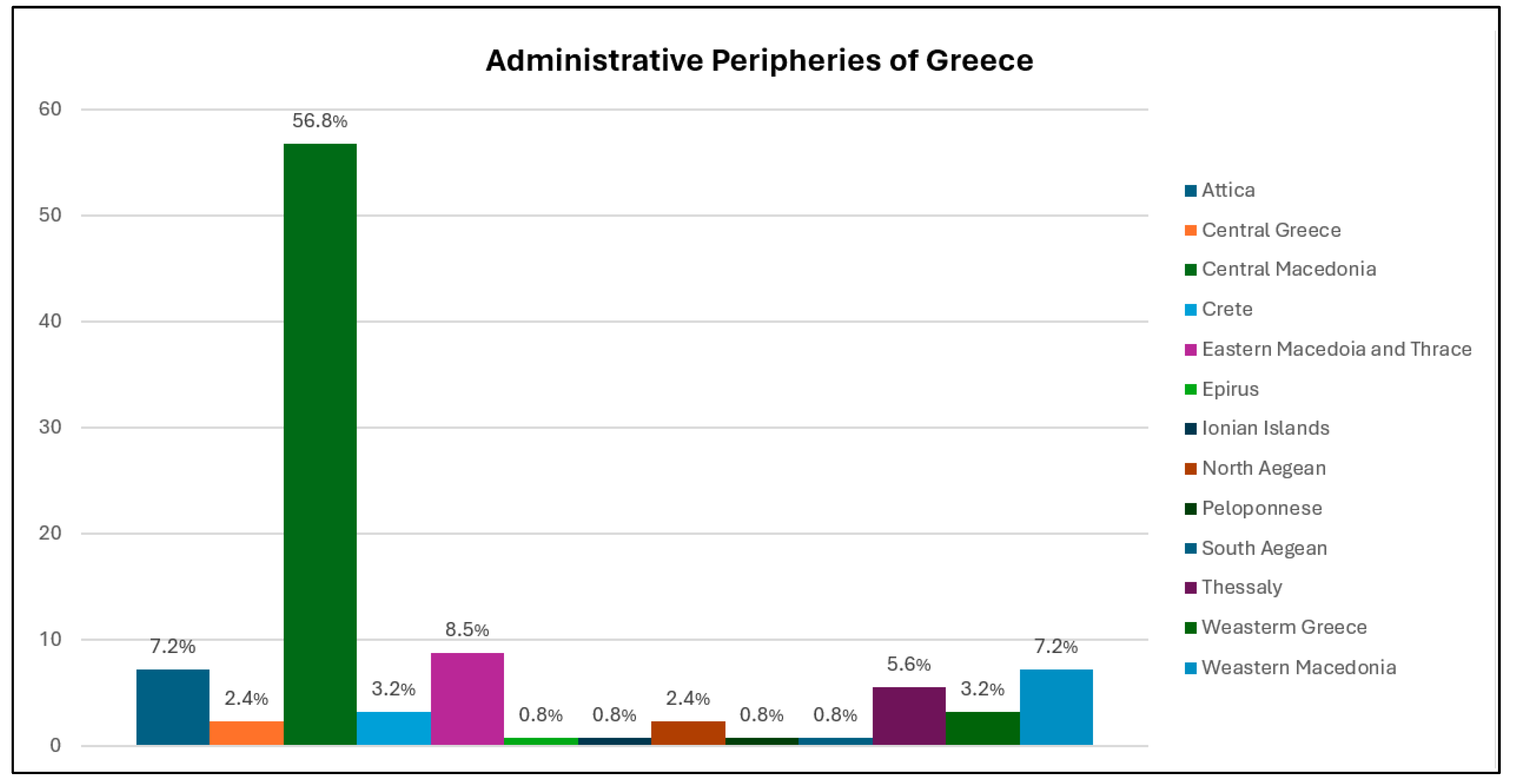

- The first section consists of three (3) demographic questions (i.e., gender—male, female, and other; age groups: 18–21 years old, 22–25 years old, and 26–28 years old; and place of residence—13 administrative peripheries of Greece);

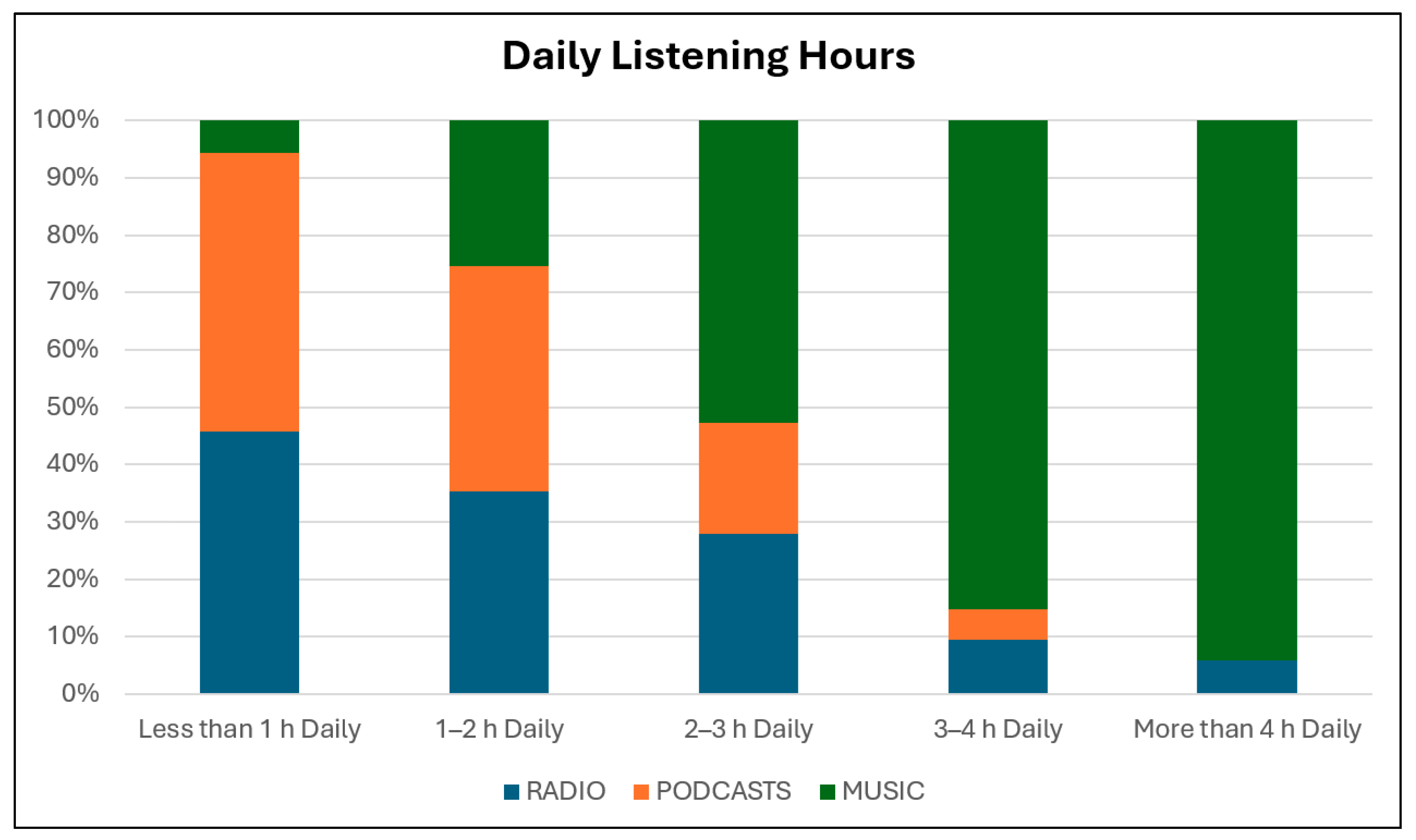

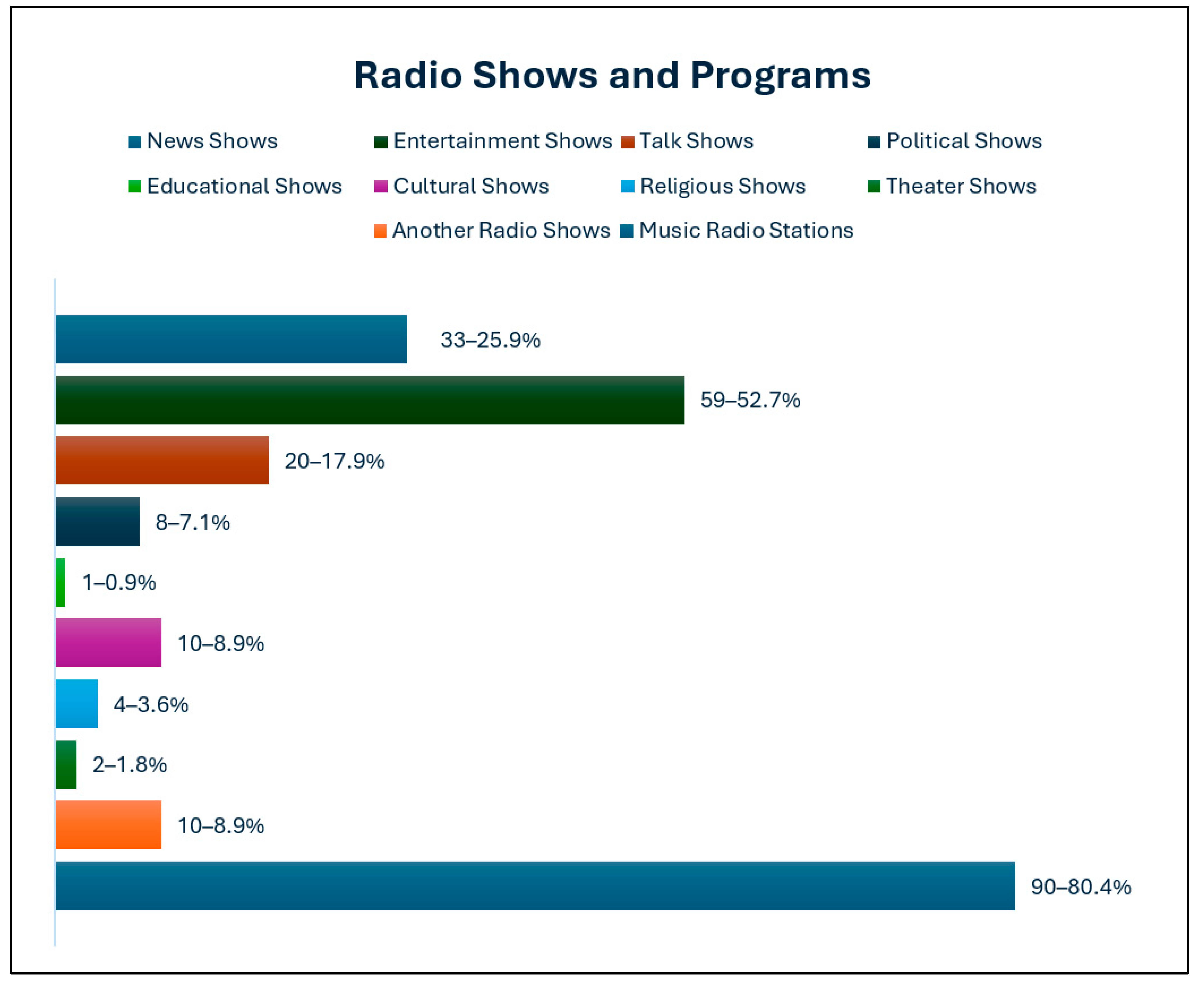

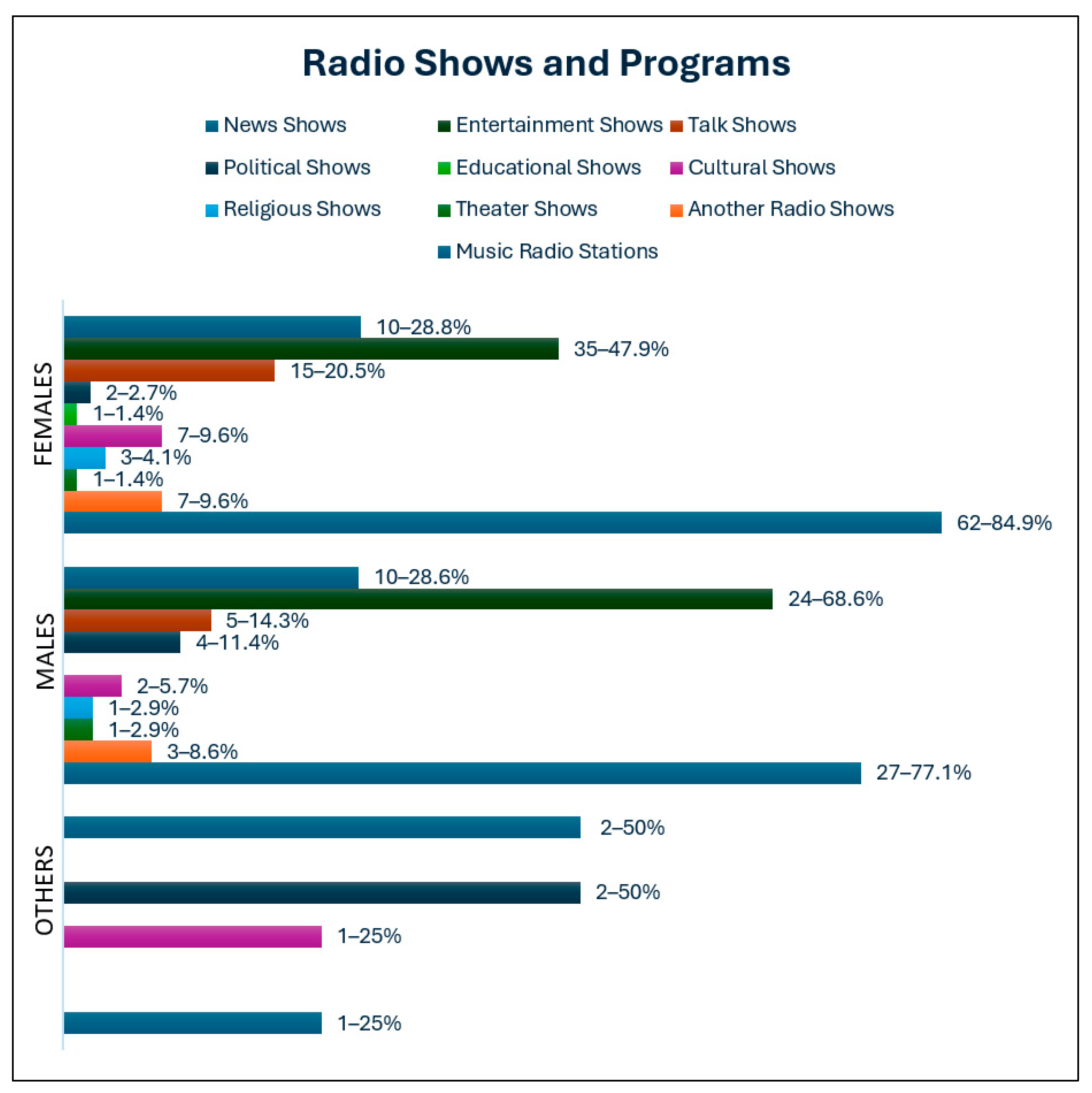

- The second section consists of six (6) questions regarding radio: (a) whether they listen to the radio with a closed-ended single-choice (i.e., ‘YES’ or ‘NO’); (b) the daily listening hours with a closed-ended single-choice (i.e., less than 1 h daily, 1–2 h daily, 2–3 h daily, 3–4 h daily, and more than 4 h daily); (c) the times of listening during day (i.e., morning, midday, afternoon, night, and after midnight) with a five-point Likert scale (i.e., ‘NEVER’, ‘SOMETIMES’, ‘OFTEN’, ‘VERY OFTEN’, and ‘ALWAYS’); (d) what radio shows and programs they usually listen to through 10 multiple-choices that were formally validated after the end of the preliminary study (i.e., news shows, entertainment shows, talk shows, political shows, educational shows, cultural shows, religious shows, theater shows, another radio shows, and music radio stations); (e) whether they listen to the radio to pass the time without being interested with a five-point Likert scale (i.e., ‘NEVER’, ‘SOMETIMES’, ‘OFTEN’, ‘VERY OFTEN’, and ‘ALWAYS’); and (f) whether they listen to the radio to keep them company when they are at home with a five-point Likert scale (i.e., ‘NEVER’, ‘SOMETIMES’, ‘OFTEN’, ‘VERY OFTEN’, and ‘ALWAYS’);

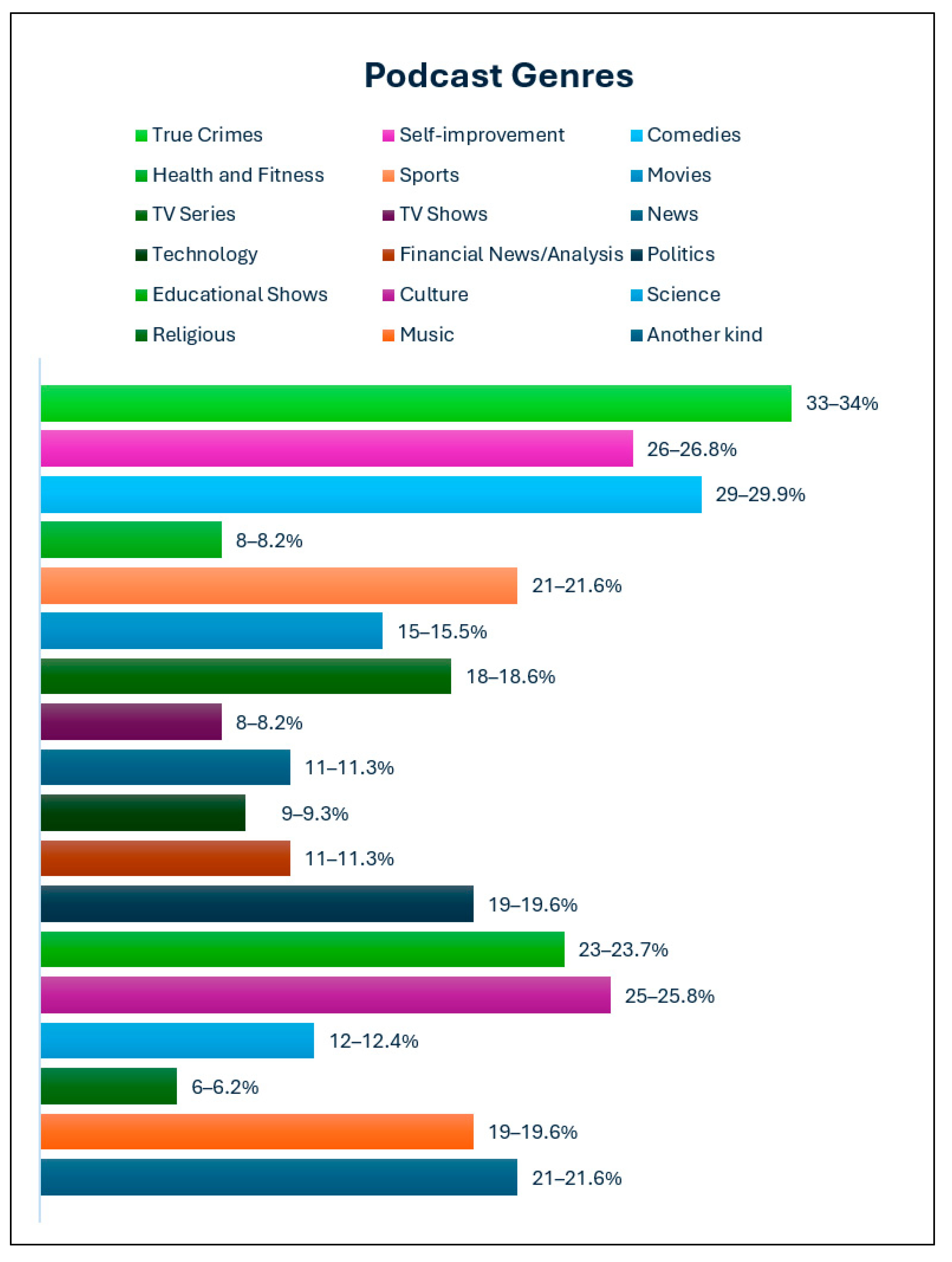

- The third section consists of three (3) questions about podcasts: (a) whether they listen to podcasts with a closed-ended single-choice (i.e., ‘YES’ or ‘NO’); (b) the daily listening hours with a closed-ended single-choice (i.e., less than 1 h daily, 1–2 h daily, 2–3 h daily, 3–4 h daily, and more than 4 h daily); and (c) what podcast genres they usually listen to through 18 multiple-choices that were formally validated after the end of the preliminary study (i.e., true crimes, self-improvement, comedies, health and fitness, sports, movies, TV series, TV shows, news, technology, financial news/analysis, politics, educational shows, culture, science, religious, music, and another kind); and finally

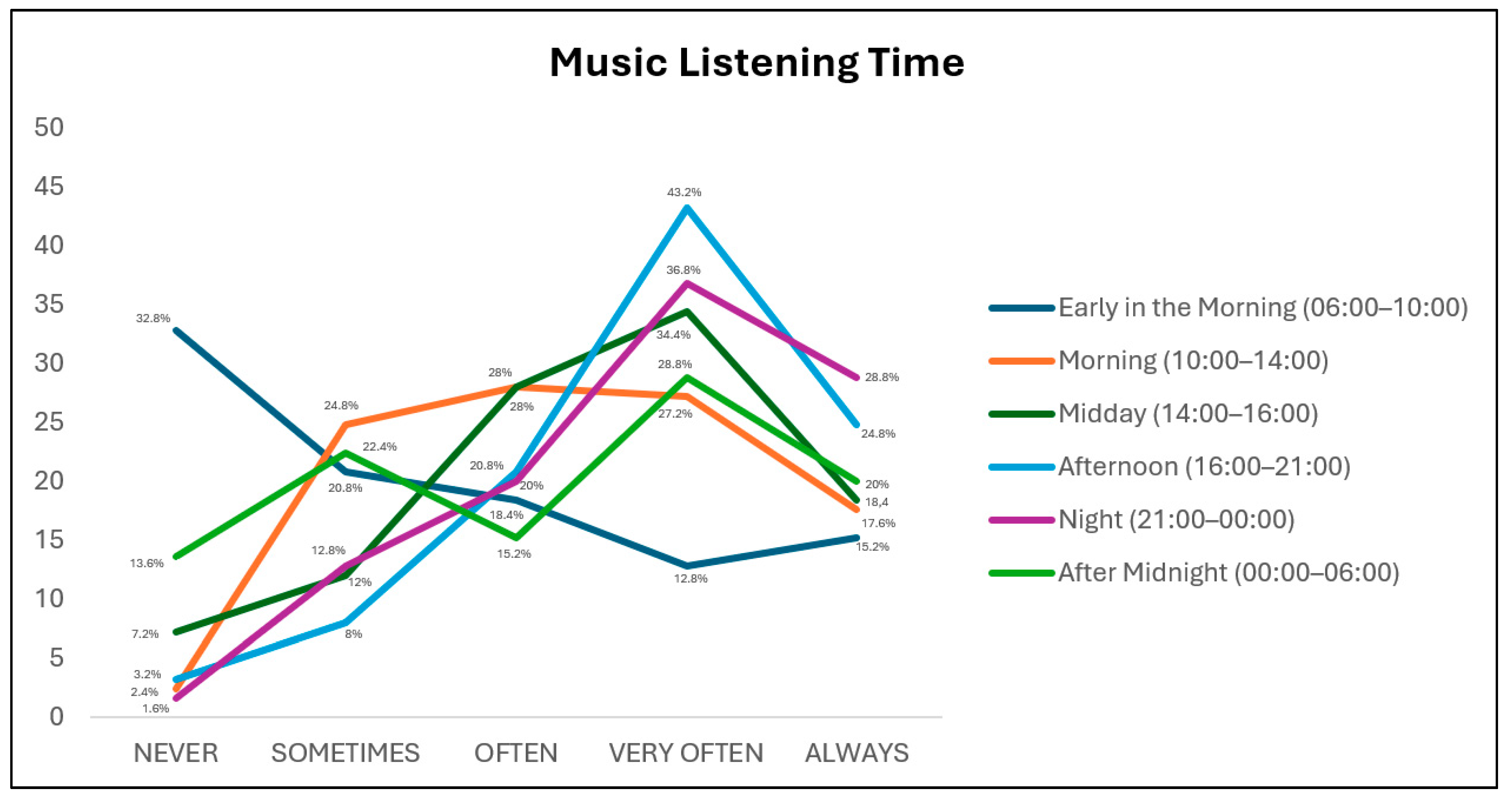

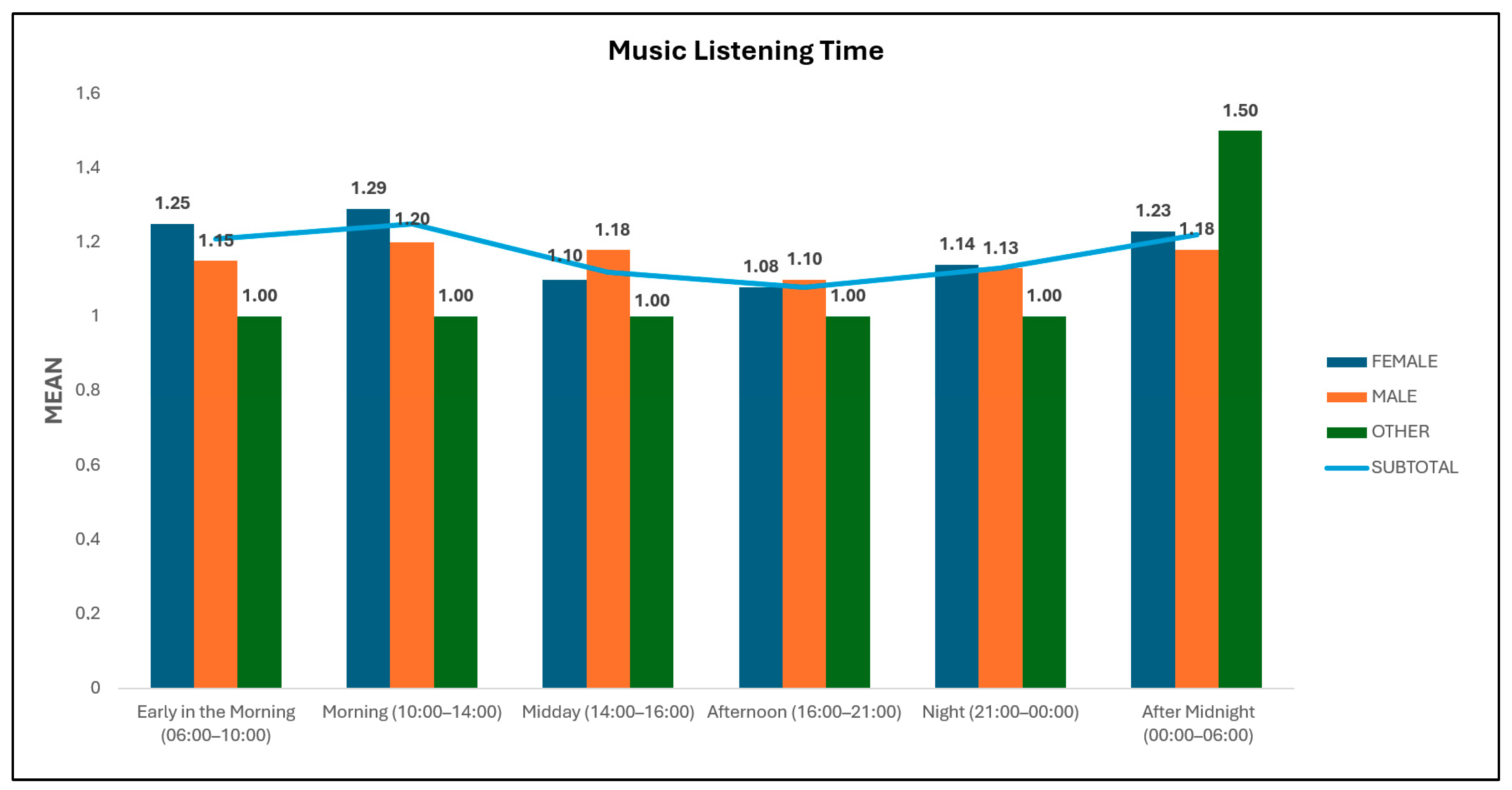

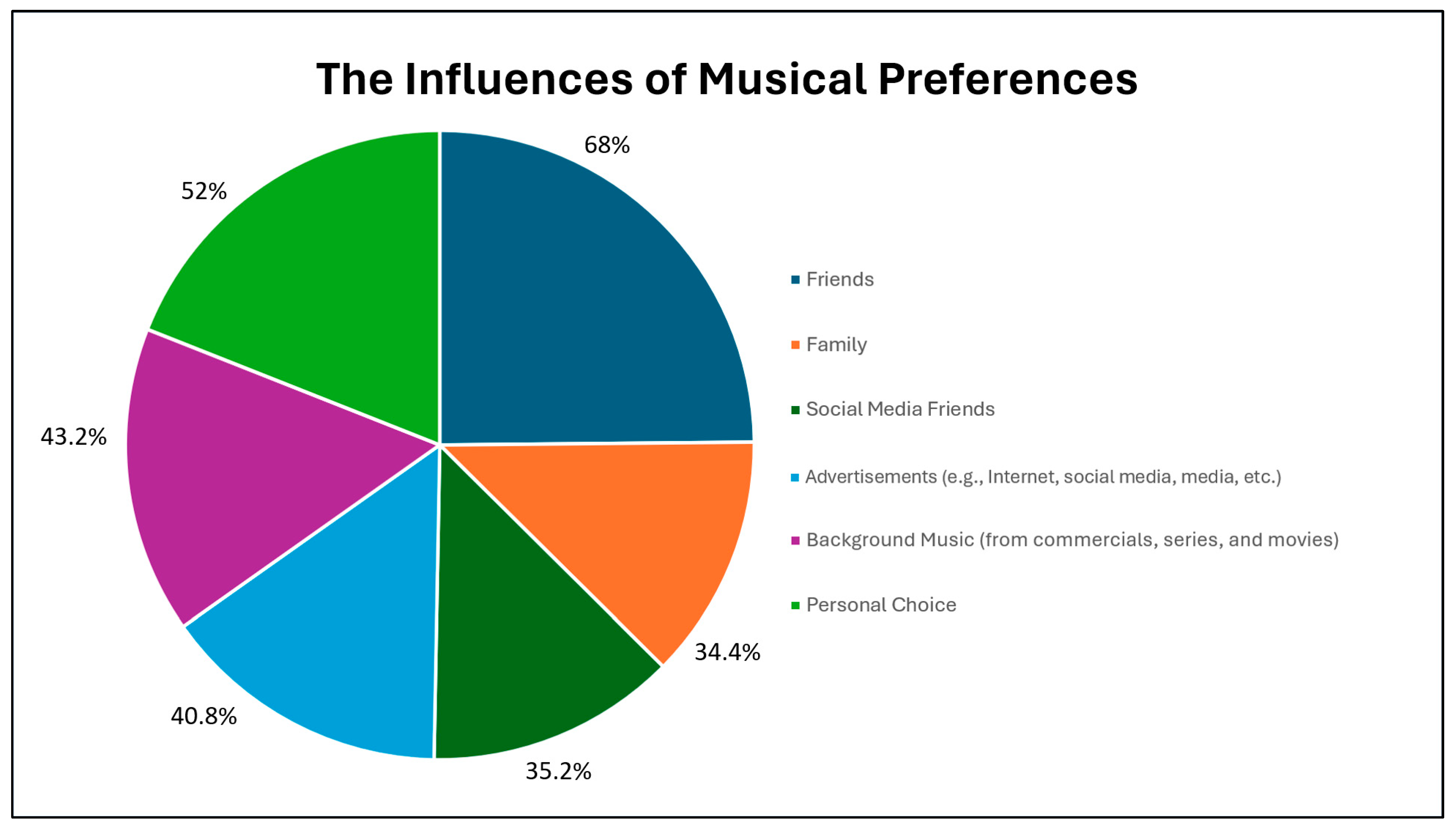

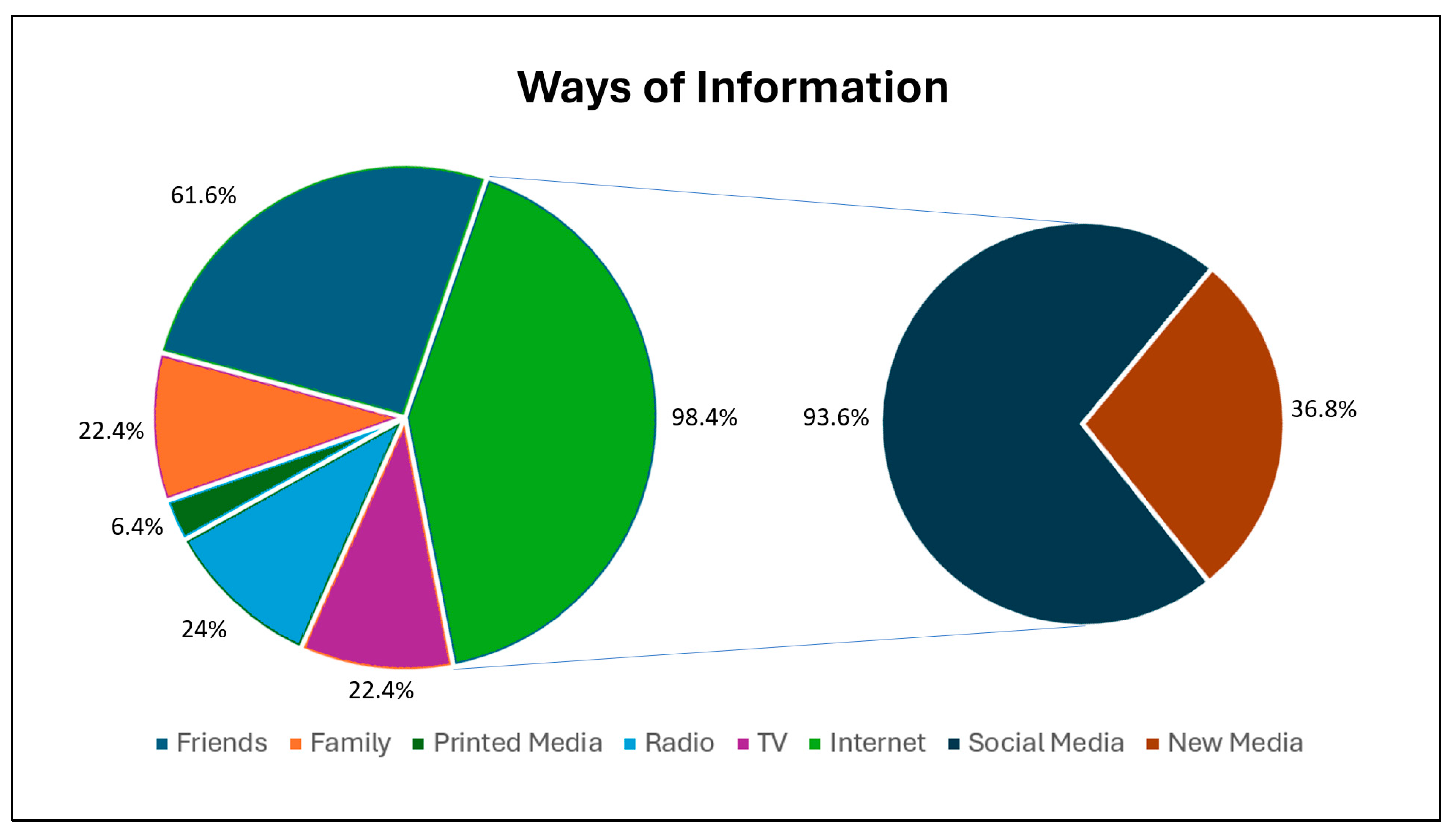

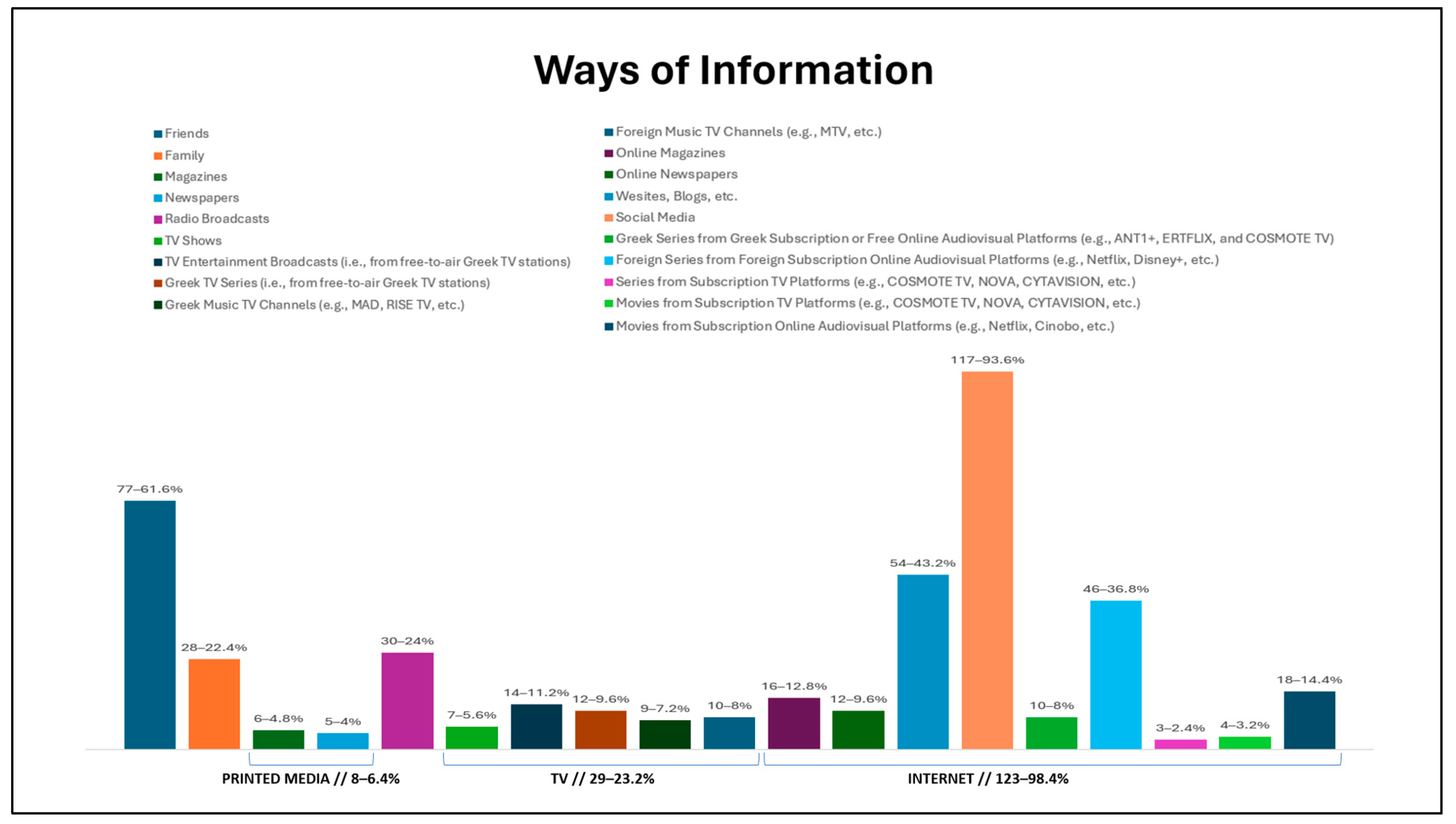

- The fourth section consists of seven (7) questions related to music: (a) whether they listen to music with a closed-ended single-choice (i.e., ‘YES’ or ‘NO’); (b) the daily listening hours with a closed-ended single-choice (i.e., less than 1 h daily, 1–2 h daily, 2–3 h daily, 3–4 h daily, and more than 4 h daily); (c) the times of listening during day (i.e., morning, midday, afternoon, night, and after midnight) with a five-point Likert scale (i.e., ‘NEVER’, ‘SOMETIMES’, ‘OFTEN’, ‘VERY OFTEN’, and ‘ALWAYS’); (d) ways of being informed on how to discover new songs and music or what they are listening to through 19 multiple-choices that were formally validated after the end of the preliminary study, which were also grouped and adjusted through 7 and 6 multiple choices, respectively, for presentation needs and better understanding (i.e., friends, family, printed media, radio, TV, and Internet—social media and new media); (e) what are the factors that influence their music preferences through 13 multiple-choices that were formally validated after the end of the preliminary study, which were grouped and adjusted through 6 multiple choices for presentation needs and better understanding (i.e., friends, family, printed media, radio, TV, and Internet); (f) whether they listen to music to pass the time without being interested with a five-point Likert scale (i.e., ‘NEVER’, ‘SOMETIMES’, ‘OFTEN’, ‘VERY OFTEN’, and ‘ALWAYS’); and (g) whether they listen to music to keep them company when they are at home with a five-point Likert scale (i.e., ‘NEVER’, ‘SOMETIMES’, ‘OFTEN’, ‘VERY OFTEN’, and ‘ALWAYS’).

3. Research Results and Findings through Discussion

3.1. Research Sample Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Radio and Music Preferences—RP

3.3. Statistical Criteria: One-Way ANOVA and Correlations

3.4. General Profile of the Participants

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| APA | American Psychological Association |

| AUTh | Aristotle University of Thessaloniki |

| CLT | Central Limit Theorem |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019—official name for the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV) coronavirus |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| GenZ | Generation Z |

| H | Hypothesis |

| ICTs | Information Communication Technologies |

| MACE | Media, Audiovisual Content, and Education |

| MEAN | Average |

| MUSE | Music Use |

| Q | Question |

| REC | Research Ethics Committee |

| RP | Research Purpose |

| SD | Standard Deviations |

| SJMC | School of Journalism and Mass Communications |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| TV | Television |

| URL | Uniform Resource Locator |

References

- American Psychological Association. 2020. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 7th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Asy’ari, Nur Aini Shofiya. 2018. The Strategy of Radio Convergence for Facing New Media Era. In International Conference on Emerging Media, and Social Science. Bratislava: European Alliance for Innovation (EAI). [Google Scholar]

- Barrios-Rubio, Andrés. 2021. From the Antenna to the Display Devices: Transformation of the Colombian Radio Industry. Journalism and Media 2: 208–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, Robin. 2002. Digital Techniques in Broadcasting Transmission, 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Focal Press. ISBN 9780240805089. First published 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Boal-Palheiros, Graça M., and David J. Hargreaves. 2001. Listening to Music at Home and at School. British Journal of Music Education 18: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet, Montse, David Fernández-Quijada, and Xavier Ribes. 2011. The Changing Natures of Public Service Radio: A case study of iCat fm. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 17: 177–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Serena. 2018. Ten Steps in Scale Development and Reporting: A Guide for Researchers. Communication Methods and Measures 12: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D. Jasun, and Mitchell T. Bard. 2023. Journalism in the Generation Z Age. London: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Horng-Jinh, Kuo-Chung Huang, and Chao-Hsien Wu. 2006. Determination of Sample Size in Using Central Limit Theorem for Weibull Distribution. Information and Management Sciences 17: 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, TanChuan, and Nikki S. Rickard. 2012. The Music USE (MUSE) Questionnaire: An Instrument to Measure Engagement in Music. Music Perception 29: 429–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, Gianna. 2022. Rock On: The State of Rock Music Among Generation Z. Honors College Theses 352. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, Amanda Jane, and Paul A. Atkinson. 1996. Making Sense of Qualitative Data: Complementary Research Strategies. Los Angeles: Sage. ISBN 9780803970533. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, Andrew L., and Howard B. Lee. 2016. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed. London: Psychology Press. First published 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Čvirik, Marián, and Monika Naďová Krošláková. 2022. The Cognitive and Affective Component of Young Consumers’ Music Perception: An Introduction to Audio Marketing Research. Ekonomika Cestovného Ruchu a Podnikanie 14: 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Deckman, Melissa, Jared McDonald, Stella Rouse, and Mileah Kromer. 2020. Gen Z, Gender, and COVID-19. Politics & Gender 16: 1019–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimoulas, Charalampos, Andreas A. Veglis, and George Kalliris. 2018. Semantically Enhanced Authoring of Shared Media. In Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology, 4th ed. Edited by Mehdi Khosrow-Pour. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 6476–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimoulas, Charalampos, Andreas Veglis, and George Kalliris. 2015. Audiovisual Hypermedia in the Semantic Web. In Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology, 3rd ed. Edited by Mehdi Khosrow-Pour. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 7594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, Ute, Barbara Müller, Svenja Rohr, John Ruhrmann, and Melissa Schäfer. 2022. Listen and Read: The Battle for Attention: A New Report About Key Audience Behaviour in the Age of eBooks, Audiobooks and Podcasts. Publishing Research Quarterly 38: 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epafras, Leonard Chrysostomos, Hendrikus Paulus Kaunang, Maksimilianus Jemali, and Vania Sharleen Setyono. 2021. Transitional Religiosity: The Religion of Generation Z. In ISRL 2020: Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Religious Life, Bogor, Indonesia, November 02–05, 2000. Edited by Yusuf Durachman, Akmal Ruhana and Ida Fitri Astuti. Bogor: EAI Publishing, pp. 247–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUR-Lex. 2016. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Fietkiewicz, Kaja J., Elmar Lins, Katsiaryna S. Baran, and Wolfgang G. Stock. 2016. Inter-generational Comparison of Social Media Use: Investigating the Online Behavior of Different Generational Cohorts. Paper presented at 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, January 5–8; Los Alamitos: IEEE, pp. 3829–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, Arlene G. 1995. How to Analyze Survey Data. Thousand Oaks: Sage. ISBN 9780803973862. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, Karen, Marc G. Weinberger, and Charles S. Gulas. 2004. The Impact of Perceived Humor, Product Type, and Humor Style in Radio Advertising. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 26: 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flew, Terry. 2014. New Media, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195577853. First published 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, Uwe. 2009. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 4th ed. London: Sage. ISBN 9781847873248. First published 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Galán-Arribas, Rafael, Francisco-Javier Herrero-Gutiérrez, and Francisco-Javier Frutos-Esteban. 2022. Podcasting: The Radio of Generation Z in Spain. Social Sciences 11: 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazi, Angeliki, Paula Cordeiro, Guy Starkey, and Dimitra Dimitrakopoulou. 2014. “Generation C” and Audio Media: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Differences in Media Consumption in Four European Countries. Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies 11: 239–57. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, Alyssa. 2019. Generation Z Re-Defining the Business of Music. Music Business Journal 13: 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, James J., and Oliver P. John. 2003. Individual Differences in Two Emotion Regulation Processes: Implications for Affect, Relationships, and Well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85: 348–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallett, Rachel, and Alexandra Lamont. 2016. Music Use in Exercise: A Questionnaire Study. Media Psychology 20: 658–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juslin, Patrik N., and Petri Laukka. 2004. Expression, Perception, and Induction of Musical Emotions: A Review and a Questionnaire Study of Everyday Listening. Journal of New Music Research 33: 217–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliri, Emilia, and Andreas Veglis. 2022. Psychological Practices Applied by Media Organizations to Data Visualizations in Relation to the Environment. Open Journal of Animation, Film and Interactive Media in Education and Culture [AFIMinEC] 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenidou, Irene, Aikaterini Stavrianea, Spyridon Mamalis, and Ifigeneia Mylona. 2020. Knowledge Assessment of COVID-19 Symptoms: Gender Differences and Communication Routes for the Generation Z Cohort. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 6964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karypidou, Christina. 2006. History of Radio. History, Organization and Operation of Radio Thessaloniki. Bachelor’s thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Karypidou, Christina, and Andreas Veglis. 2022. Visualization Tools for Producing Environmental Data Journalism Articles. Annual Greek-Speaking Scientific Conference of Communication Laboratories 1: 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Karypidou, Christina, Charalampos Bratsas, and Andreas Veglis. 2019. Visualization and Interactivity in Data Journalism Projects. Strategy & Development Review 9: 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kontogiannatou, Gerasimina. 2018. Mixed-Methods Research: The Logic Behind its Design and the Framework for Its Implementation. Academia 12: 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Martyn, Kieran Bromley, Chris Sutton, Gareth Mccray, Helen Lucy Myers, and Gillian A. Lancaster. 2021. Determining Sample Size for Progression Criteria for Pragmatic Pilot RCTs: The Hypothesis Test Strikes Back! Pilot and Feasibility Studies 7: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaye, Robin Ceasar F., and Mary Ann E. Tarusan. 2023. The Old and The New: Radio and Social Media Convergence. International Journal of Communication and Media Science 10: 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolika, Maria, Rigas Kotsakis, Maria Matsiola, and George Kalliris. 2022. Direct and Indirect Associations of Personality with Audiovisual Technology Acceptance through General Self-Efficacy. Psychological Reports 125: 1165–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsiola, Maria G. 2008. New Technological Tools in Contemporary Journalism: Study Concerning Their Utilization by the Greek Journalists Related to the Use of the Internet as a Mass Medium. Ph.D. thesis, School of Journalism and Mass Communications, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsiola, Maria, Panagiotis Spiliopoulos, Rigas Kotsakis, Constantinos Nicolaou, and Anna Podara. 2019. Technology-Enhanced Learning in Audiovisual Education: The Case of Radio Journalism Course Design. Education Sciences 9: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, Mumtaz Ali, Hiram Ting, Jun-Hwa Cheah, Ramayah Thurasamy, Francis Chuah, and Tat Huei Cham. 2020. Sample Size for Survey Research: Review and Recommendations. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling 4: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, J. Tom, and Lauren E. Mullenbach. 2018. Looking for a White Male Effect in Generation Z: Race, Gender, and Political Effects on Environmental Concern and Ambivalence. Society & Natural Resources 31: 925–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, Constantinos. 2021. Media Trends and Prospects in Educational Activities and Techniques for Online Learning and Teaching through Television Content: Technological and Digital Socio-Cultural Environment, Generations, and Audiovisual Media Communications in Education. Education Sciences 11: 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, Constantinos. 2023. Generations and Branded Content from and through the Internet and Social Media: Modern Communication Strategic Techniques and Practices for Brand Sustainability—The Greek Case Study of LACTA Chocolate. Sustainability 15: 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, Constantinos. 2024. Defining the Sound Preferences of Generation Z. Paper presented at 10th International Scientific Conference on Social and Educational Adaptability, Heraklion, Greece, May 16. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou, Constantinos, and Maria Matsiola. 2023a. Cross-Cultural Methodology for Translating and Weighting Foreign Language Questionnaires: The Case of an International Cross-Cultural Translation Model. Paper presented at 9th International Scientific Conference on Citizen, Education and Political Participation, Heraklion, Greece, May 27. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou, Constantinos, and Maria Matsiola. 2023b. Getting to know Generation Z again through Audio-based Teaching. Paper presented at 9th International Scientific Conference on Citizen, Education and Political Participation, Heraklion, Greece, May 27. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou, Constantinos, Anna Podara, and Christina Karypidou. 2021b. Audiovisual Media in Education and Generation Z: Application of Audiovisual Media Theory in Education with an Emphasis on Radio. Paper presented at 6th International Scientific Conference on Communication, Information, Awareness and Education in Late Modernity, Heraklion, Greece, July 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou, Constantinos, Maria Matsiola, and George Kalliris. 2022. The Challenge of an Interactive Audiovisual-Supported Lesson Plan: Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) in Adult Education. Education Sciences 12: 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, Constantinos, Maria Matsiola, Charalampos Dimoulas, and George Kalliris. 2024. Outlining the Ethos of Generation Z from and through Music and Radio. Envisioning the Future of Communication 2. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou, Constantinos, Maria Matsiola, Christina Karypidou, Anna Podara, Rigas Kotsakis, and George Kalliris. 2021a. Media Studies, Audiovisual Media Communications, and Generations: The Case of Budding Journalists in Radio Courses in Greece. Journalism and Media 2: 155–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nu”azzidane, Bakhtiar Rafqi, and Zahrotus Sa’idah. 2023. Good Morning Young People: Geronimo Fm Radio’s Efforts to Maintain Existence in Generation Z. Professional: Jurnal Komunikasi Dan Administrasi Publik 10: 881–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, Adaobi Olivia, Julius Chibuike Nwosu, and Gloria Nneka Ono. 2020. Use of Radio as a Tool of Learning in Crisis Period. Nnamdi Azikiwe University Journal of Communication and Media Studies 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandusaputri, Nindyo Andayaning, Rachmat Bintang Ramadhan Mokodompit, and Irwansyah. 2024. Peminat Radio dan Podcast Kalangan Generasi Z Saat Berkendara. Jurnal Ilmu Komunikasi Dan Media Sosial (JKOMDIS) 4: 179–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanastasiou, Constantinos, and Elena C. Papanastasiou. 2005. Methodology of Educational Research. Nicosia: Authors. [Google Scholar]

- Papanis, Efstratios. 2011. Research Methodology and Internet. Athens: Sideris. [Google Scholar]

- Paschalidis, Grigoris, and Dimitra L. Milioni. 2010. Challenging the Journalistic Habitus? Journalism Students’ Media Use and Attitudes Towards Mainstream and Alternative Media. Paper presented at World Journalism Education Congress, Grahamstown, South Africa, July 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pilitsidou, Zacharenia, Nikolaos Tsigilis, and George Kalliris. 2019. Radio Stations and Audience Communication: Social Media Utilization and Listeners Interaction. Issues in Social Science 7: 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzolitto, Elia. 2023. Music in Business and Management Studies: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Management Review Quarterly, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podara, Anna, and Emilia Kalliri. 2023. Defining TV Watching Experience: Psycho-Social Factors and Screen Culture of Generation Z. Envisioning the Future of Communication 1: 103–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podara, Anna, Maria Matsiola, Constantinos Nicolaou, Theodora A. Maniou, and George Kalliris. 2019. Audiovisual Consumption Practices in Post-Crisis Greece: An Empirical Research Approach to Generation Z. Paper presented at International Conference on Filmic and Media Narratives of the Crisis: Contemporary Representations, Athens, Greece, November 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Podara, Anna, Maria Matsiola, Constantinos Nicolaou, Theodora A. Maniou, and George Kalliris. 2022. Transformation of Television Viewing Practices in Greece: Generation Z and Audio-Visual Content. Journal of Digital Media & Policy 13: 157–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podara, Anna N. 2021. Internet, Audiovisual Content and New Media: Television and Watching Habits of Generation Z. Ph.D. thesis, School of Journalism and Mass Communications, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspitasari, Euis Evi, Ulfa Yuniati, and Yusron Mu’tasim Billah. 2020. The Existence of Bandung Private Radio through Survey of Generation Z Needs. Medio 1: 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert-Agell, Francesc, Santiago Justel-Vazquez, and Montse Bonet. 2022. No habit, No Listening. Radio and Generation Z: Snapshot of the Audience Data and the Business Strategy to Connect with it. Profesional De La Información 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, John. T. 1975. Fundamental Research Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Roussou, Nayia. 1996. Factors of Humanitarian and Mass Culture and Aggressiveness in Children and Young People. The Cyprus Review 8: 38–78. [Google Scholar]

- Roussou, Nayia. 2001. Television and the Cultural Identity of Cyprus Youth. Nicosia: Intercollege Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saragih, Harriman Samuel. 2016. Music for the Generation-Z, Quo Vadis. In 2016 Global Conference on Business, Management and Entrepreneurship. Amsterdam: Atlantis Press, pp. 844–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellas, Toni. 2013. Ràdio i Contingutssonors. Del Mitjàanalògictradicional a La Recerca de Nous Models de Negoci de L’àudio Digital. Trípodos 33: 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan, Halim Adiputra, Grace Gerungan, and Astri Yogatama. 2020. Uses and Gratification of Community Radio: A Case Study of Petra Campus Radio. Nusantara Science and Technology Proceedings, May. Malang, Indonesia, 410–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutaleva, Anna. V., Milana V. Golysheva, Yulia V. Tsiplakova, and Andrei Yu. Dudchik. 2020. Media Education and the Formation of the Legal Culture of Society. Perspektivy Nauki i Obrazovania—Perspectives of Science and Education 45: 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siardos, Georgios K. 2005. Methodology of Social Research, 2nd ed. Thessaloniki: Ziti. [Google Scholar]

- Smaliukiene, Rasa, Elena Kocai, and Angele Tamuleviciute. 2020. Generation Z and Consumption: How Communication Environment Shapes Youth Choices. Media Studies 11: 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srirahayu, Dyah Puspitasari, Muhammad Rifky Nurpratama, Tanti Handriana, and Sri Hartini. 2022. Effect of Gender, Social Influence, and Emotional Factors in Usage of e-Books by Generation Z in Indonesia. Digital Library Perspectives 38: 263–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stareček, Augustín, Dagmar Caganova, Eliska Kubisova, Gyurák Babeľová, Filip Fabian, and Andrea Chlpekov. 2020. The Importance of Generation Z Personality and Gender Diversity in the Development of Managerial Skills. In 2020 18th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA). Piscataway: IEEE, pp. 658–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacchi, Jo. 2000. The Need for Radio Theory in the Digital Age. International Journal of Cultural Studies 3: 289–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talabi, Felix Olajide, and Lydia Oko-Epelle. 2024. Influence of Radio Messages on the Awareness and Adoption of Malaria Preventive Measures among Rural Dwellers in South-West Nigeria. Journalism and Media 5: 271–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, Anita Sari. 2024. The Effectiveness of the Role of Social Media in Premarital Education for Generation Z in Purwakarta Regency, Indonesia. Arkus 10: 508–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Shirley. 2004. Model Business Letters, E-mails & Other Business Documents, 6th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Terol-Bolinches, Raúl, Mónica Pérez-Alaejos, and Andrés Barrios-Rubio. 2022. Podcast Production and Marketing Strategies on the Main Platforms in Europe, North America, and Latin America. Situation and Perspectives. El Profesional de la Información 31: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabane, Lehana, Jinhui Ma, Rong Chu, Ji Cheng, Afisi Ismaila, Lorena P. Rios, Reid Robson, Marroon Thabane, Lora Giangregorio, and Charles H. Goldsmith. 2010. A Tutorial on Pilot Studies: The What, Why and How. BMC Medical Research Methodology 10: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomyuk, Olga N., and Olga A. Avdeeva. 2022. Digital Transformation of the Global Media Market: In Search for New Media Formats. Economic Consultant 37: 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño Benavides, Teresa Berenice, Ana Teresa Alcorta Castro, Sofia Alejandra Garza Marichalar, Mariamiranda Peña Cisneros, and Elena Catalina Baker Suárez. 2023. Understanding Generation Z and Social Media Addiction. In Social Media Addiction in Generation Z Consumers: Implications for Business and Marketing. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vryzas, Nikolaos, Nikolaos Tsipas, and Charalampos Dimoulas. 2020. Web Radio Automation for Audio Stream Management in the Era of Big Data. Information 11: 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, Paul D., Alan J. Swope, and Frederick J. Heide. 2006. The Music Experience Questionnaire: Development and Correlates. The Journal of Psychology 140: 329–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Ann. 2003. How to… Write and Analyse a Questionnaire. Journal of Orthodontics 30: 245–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Kaylene C., and Robert A. Page. 2011. Marketing to the Generations. Journal of Behavioral Studies 3: 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Kaylene C., Robert A. Page, Alfred R. Petrosky, and Edward H. Hernandez. 2010. Multi-generational Marketing: Descriptions, Characteristics, Lifestyles, and Attitudes. Journal of Applied Business and Economics 11: 21. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yihang. 2022. Exploring Ways to Make Generation Z like Classical Music Better. In 2021 International Conference on Social Development and Media Communication (SDMC 2021). Amsterdam: Atlantis Press, pp. 1514–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

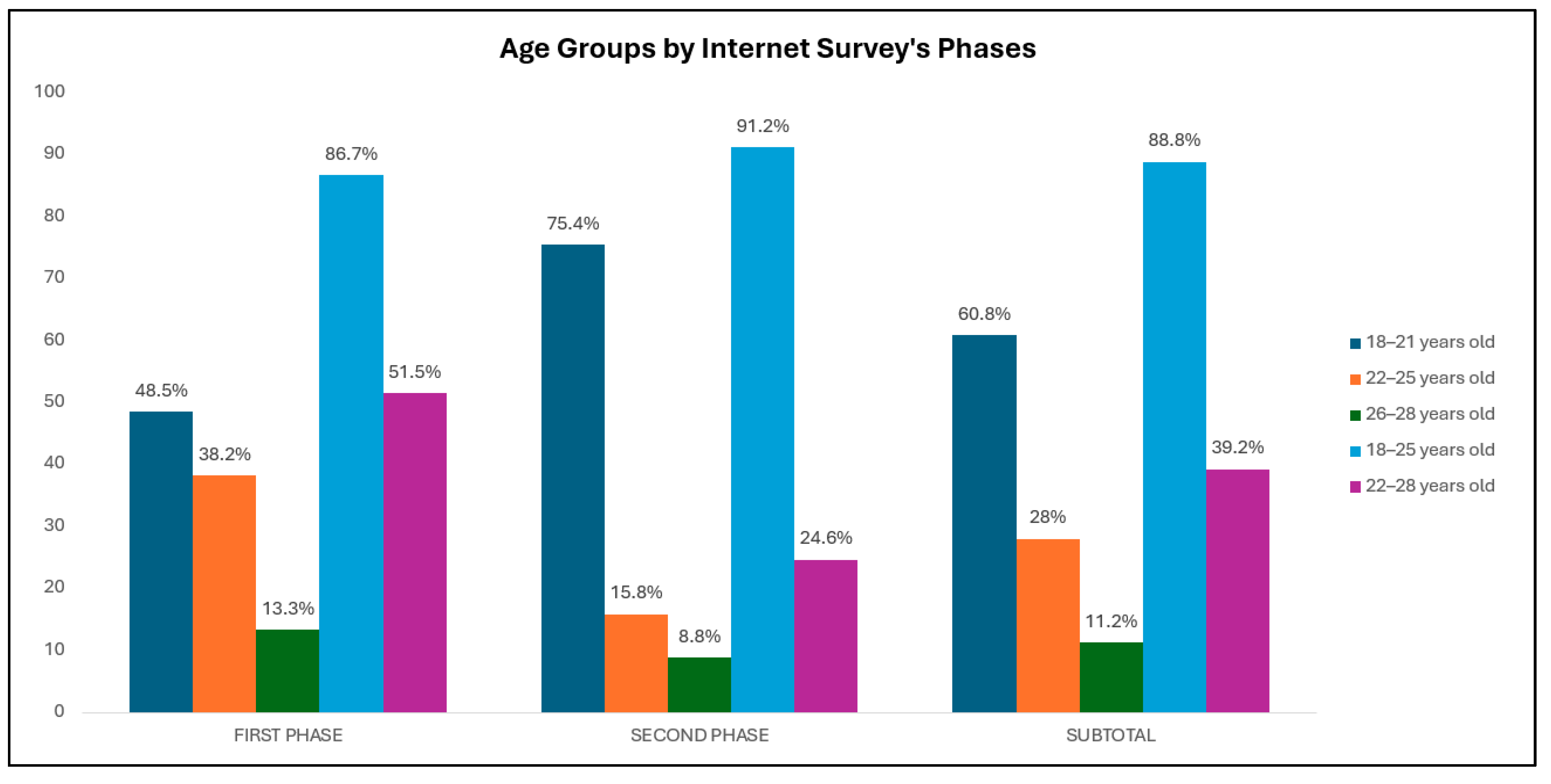

| Age Groups | First Phase | Second Phase | Subtotal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–21 years old | 33–48.5% | 43–75.4% | 76–60.8% |

| 22–25 years old | 26–38.2% | 9–15.8% | 35–28% |

| 26–28 years old | 9–13.3% | 5–8.8% | 14–11.2% |

| 18–25 years old | 59–86.7% | 52–91.2% | 111–88.8% |

| 22–28 years old | 35–51.5% | 14–24.6% | 49–39.2% |

| Subtotal | 68–54.4%—100% | 57–45.6%—100% | 125–100% |

| Gender | 18–21 Years Old | 22–25 Years Old | 26–28 Years Old | Subtotal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

| Female | 53 | 69.7 | 42.4 | 18 | 51.4 | 14.5 | 8 | 57.1 | 6.3 | 79 | 63.2 |

| Male | 20 | 26.3 | 16 | 14 | 40 | 11.2 | 6 | 42.9 | 4.8 | 40 | 32 |

| Other | 3 | 4 | 2.4 | 3 | 8.6 | 2.4 | - | - | - | 6 | 4.8 |

| Subtotal | 76 | 100 | 60.8 | 35 | 100 | 28.1 | 14 | 100 | 11.1 | 125 | 100 |

| Sample Listening | Sample Not Listening | N | Less than 1 h Daily | 1–2 h Daily | 2–3 h Daily | 3–4 h Daily | More than 4 h Daily | N | MEAN | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RADIO | 112–89.6% | 13–10.4% | 125 | 72–64.3% | 25–22.3% | 10–8.9% | 2–1.8% | 3–2.7% | 112 | 1.56 | 0.928 |

| PODCASTS | 97–77.6% | 28–22.4% | 66–68% | 24–24.7% | 6–6.2% | 1–1% | - | 97 | 1.40 | 0.656 | |

| MUSIC | 125–100% | - | 10–8% | 20–16% | 21–16.8% | 20–16% | 54–43.2% | 125 | 3.70 | 1.374 |

| Gender | Sample Listening | Sample Not Listening | N | Less than 1 h Daily | 1–2 h Daily | 2–3 h Daily | 3–4 h Daily | More than 4 h Daily | N | MEAN | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RADIO | Female | 73–92.4% | 6–7.6% | 125 | 49–67.1% | 18–24.7% | 6–8.2% | - | - | 112 | 1.41 | 0.642 |

| Male | 35–87.5% | 5–12.5% | 22–62.9% | 4–11.4% | 4–11.4% | 2–5.7% | 3–8.6% | 1.86 | 1.332 | |||

| Other | 4–66.7% | 2–33.3% | 1–25% | 3–75% | - | - | - | 1.75 | 0.500 | |||

| PODCASTS | Female | 65–82.3% | 14–17.7% | 125 | 49–75.4% | 11–16.9% | 4–6.2% | 1–1.5% | - | 97 | 1.34 | 0.668 |

| Male | 27–67.5% | 13–32.5% | 15–55.6% | 10–37% | 2–7.4% | - | - | 1.52 | 0.643 | |||

| Other | 5–83.3% | 1–16.7% | 2–40% | 3–60% | - | - | - | 1.60 | 0.548 | |||

| MUSIC | Female | 79–100% | - | 125 | 5–6.3% | 10–12.7% | 18–22.8% | 16–20.3% | 30–38% | 125 | 3.71 | 1.273 |

| Male | 40–100% | - | 5–12.5% | 10–25% | - | 4–10% | 21–52.5% | 3.65 | 1.610 | |||

| Other | 6–100% | - | - | - | 3–50% | - | 3–50% | 4.00 | 1.095 |

| NEVER | SOMETIMES | OFTEN | VERY OFTEN | ALWAYS | N | MEAN | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early in the Morning (06:00–10:00) | 58–51.8% | 26–23.2% | 17–15.2% | 5–4.5% | 6–6.4% | 112 | 1.88 | 1.153 |

| Morning (10:00–14:00) | 19–17% | 46–41.1% | 33–29.5% | 11–9.8% | 3–2.7% | 112 | 2.40 | 0.972 |

| Midday (14:00–16:00) | 30–26.8% | 48–42.9% | 26–23.2% | 8–7.1% | - | 112 | 2.11 | 0.884 |

| Afternoon (16:00–21:00) | 19–17% | 41–36.6% | 36–32.1% | 13–11.6% | 3–2.7% | 112 | 2.46 | 0.995 |

| Night (21:00–00:00) | 32–28.6% | 38–33.9% | 23–20.5% | 16–14.3% | 3–2.7% | 112 | 2.29 | 1.110 |

| After Midnight (00:00–06:00) | 56–50% | 40–35.7% | 7–6.3% | 7–6.3% | 2–1.8% | 112 | 1.74 | 0.956 |

| Early in the Morning (06:00–10:00) | Morning (10:00–14:00) | Midday (14:00–16:00) | Afternoon (16:00–21:00) | Night (21:00–00:00) | After Midnight (00:00–06:00) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | N | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 |

| Mean | 1.85 | 2.44 | 2.14 | 2.59 | 2.23 | 1.60 | |

| SD | 1.175 | 0.943 | 0.918 | 0.925 | 1.034 | 0.795 | |

| Male | N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Mean | 1.86 | 2.29 | 2.06 | 2.09 | 2.26 | 1.86 | |

| SD | 1.141 | 1.073 | 0.873 | 1.011 | 1.221 | 1.115 | |

| Other | N | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mean | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.00 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.25 | |

| SD | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.957 | |

| Subtotal | N | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 |

| Mean | 1.88 | 2.40 | 2.11 | 2.46 | 2.29 | 1.74 | |

| SD | 1.153 | 0.972 | 0.884 | 0.995 | 1.110 | 0.956 |

| NEVER | SOMETIMES | OFTEN | VERY OFTEN | ALWAYS | N | MEAN | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early in the Morning (06:00–10:00) | 41–32.8% | 26–20.8% | 23–18.4% | 16–12.8% | 19–15.2% | 125 | 1.21 | 0.408 |

| Morning (10:00–14:00) | 3–2.4% | 31–24.8% | 35–28% | 34–27.2% | 22–17.6% | 125 | 1.25 | 0.434 |

| Midday (14:00–16:00) | 9–7.2% | 15–12% | 35–28% | 43–34.4% | 23–18.4% | 125 | 1.12 | 0.326 |

| Afternoon (16:00–21:00) | 4–3.2% | 10–8% | 26–20.8% | 54–43.2% | 31–24.8% | 125 | 1.08 | 0.272 |

| Night (21:00–00:00) | 2–1.6% | 16–12.8% | 25–20% | 46–36.8% | 36–28.8% | 125 | 1.13 | 0.335 |

| After Midnight (00:00–06:00) | 17–13.6% | 28–22.4% | 19–15.2% | 36–28.8% | 25–20% | 125 | 1.22 | 0.419 |

| Early in the Morning (06:00–10:00) | Morning (10:00–14:00) | Midday (14:00–16:00) | Afternoon (16:00–21:00) | Night (21:00–00:00) | After Midnight (00:00–06:00) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | N | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 |

| MEAN | 1.25 | 1.29 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.14 | 1.23 | |

| SD | 0.438 | 0.457 | 0.304 | 0.267 | 0.348 | 0.422 | |

| Male | N | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| MEAN | 1.15 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 1.10 | 1.13 | 1.18 | |

| SD | 0.362 | 0.405 | 0.385 | 0.304 | 0.335 | 0.385 | |

| Other | N | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| MEAN | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.50 | |

| SD | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.548 | |

| Subtotal | N | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 |

| MEAN | 1.88 | 2.40 | 2.11 | 2.46 | 2.29 | 1.74 | |

| SD | 1.153 | 0.972 | 0.884 | 0.995 | 1.110 | 0.956 |

| NEVER | SOMETIMES | OFTEN | VERY OFTEN | ALWAYS | N | MEAN | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I listen to the radio to pass the time without being interested. | 18–16.1% | 45–40.2% | 36–32.1% | 11–9.8% | 2–1.8% | 112 | 2.41 | 0.935 |

| I listen to music to pass the time without being interested. | 9–7.2% | 23–18.4% | 42–33.6% | 30–24% | 21–16.8% | 125 | 3.25 | 1.155 |

| I listen to the radio to keep me company when I’m at home. | 33–29.5% | 36–32.1% | 17–15.2% | 16–14.3% | 10–8.9% | 112 | 2.41 | 1.291 |

| I listen to music to keep me company when I’m at home. | 3–2.4% | 13–10.4% | 27–21.6% | 39–31.2% | 43–34.4% | 125 | 3.85 | 1.086 |

| Gender | Friends | Family | Social Media Friends | Advertisements | Background Music | Personal Choice | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 52–65.8% | 32–40.5% | 22–27.8% | 37–46.8% | 37–46.8% | 47–59.5% | 79 |

| Male | 27–67.5% | 11–27.5% | 16–40% | 10–25% | 14–35% | 18–45% | 40 |

| Other | 6–100% | - | 6–100% | 4–66.7% | 3–50% | - | 6 |

| Subtotal | 85–68% | 43–34.4% | 44–35.2% | 51–40.8% | 54–43.2% | 65–52% | 125 |

| Gender | Friends | Family | Printed Media | Radio | TV | Internet | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 49–62% | 22–27.8% | 2–2.5% | 21–26.6% | 19–24.1% | 77–97.5% | 79 |

| Male | 22–55% | 3–7.5% | 6–15% | 9–22.5% | 9–22.5% | 40–100% | 40 |

| Other | 6–100% | 3–50% | - | - | 1–16.7% | 6–100% | 6 |

| Subtotal | 77–61.6% | 28–22.4% | 8–6.4% | 30–24% | 29–23.2% | 123–98.4% | 125 |

| Gender | Ν | MEAN | SD | F | df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RADIO | Female | 73 | 112 | 1.41 | 0.642 | 2.917 | 2.109 |

| Male | 35 | 1.86 | 1.332 | ||||

| Other | 4 | 1.75 | 0.500 | ||||

| PODCASTS | Female | 65 | 97 | 1.34 | 0.668 | 0.958 | 2.940 |

| Male | 27 | 1.52 | 0.643 | ||||

| Other | 5 | 1.60 | 0.548 | ||||

| MUSIC | Female | 79 | 125 | 3.71 | 1.273 | 0.168 | 2.122 |

| Male | 40 | 3.65 | 1.610 | ||||

| Other | 6 | 4.00 | 1.095 | ||||

| Correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | |||

| Q1 | RADIO | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.384 ** | 0.287 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.002 | |||

| N | 112 | 88 | 112 | ||

| Q2 | PODCASTS | Pearson Correlation | 0.384 ** | 1 | 0.198 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.052 | |||

| N | 88 | 97 | 97 | ||

| Q3 | MUSIC | Pearson Correlation | 0.287 ** | 0.198 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.052 | |||

| N | 112 | 97 | 125 | ||

| Correlations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ν | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | |||

| Q1 | RADIO | 112 | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.331 ** | 0.356 ** | 0.211 * | 0.300 ** | 0.210 * | 0.359 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.000 | ||||

| Q2 | Early in the Morning (06:00–10:00) | 112 | Pearson Correlation | 0.331 ** | 1 | 0.404 ** | 0.065 | 0.150 | 0.139 | 0.218 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.493 | 0.116 | 0.145 | 0.021 | ||||

| Q3 | Morning (10:00–14:00) | 112 | Pearson Correlation | 0.356 ** | 0.404 ** | 1 | 0.411 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.176 | 0.336 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.063 | 0.000 | ||||

| Q4 | Midday (14:00–16:00) | 112 | Pearson Correlation | 0.211 * | 0.065 | 0.411 ** | 1 | 0.465 ** | 0.391 ** | 0.364 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.025 | 0.493 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Q5 | Afternoon (16:00–21:00) | 112 | Pearson Correlation | 0.300 ** | 0.150 | 0.262 ** | 0.465 ** | 1 | 0.458 ** | 0.317 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.116 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | ||||

| Q6 | Night (21:00–00:00) | 112 | Pearson Correlation | 0.210 * | 0.139 | 0.176 | 0.391 ** | 0.458 ** | 1 | 0.588 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.026 | 0.145 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Q7 | After Midnight (00:00–06:00) | 112 | Pearson Correlation | 0.359 ** | 0.218 * | 0.336 ** | 0.364 ** | 0.317 ** | 0.588 ** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | ||||

| Correlations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ν | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | |||

| Q1 | MUSIC | 125 | Pearson Correlation | 1 | −0.004 | −0.187 * | −0.082 | −0.324 ** | −0.285 ** | −0.318 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.961 | 0.037 | 0.363 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | ||||

| Q2 | Early in the Morning (06:00–10:00) | 125 | Pearson Correlation | −0.004 | 1 | 0.116 | −0.129 | −0.078 | −0.137 | 0.103 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.961 | 0.196 | 0.153 | 0.384 | 0.127 | 0.254 | ||||

| Q3 | Morning (10:00–14:00) | 125 | Pearson Correlation | −0.187 * | 0.116 | 1 | 0.130 | −0.169 | 0.057 | 0.091 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.037 | 0.196 | 0.149 | 0.059 | 0.526 | 0.311 | ||||

| Q4 | Midday (14:00–16:00) | 125 | Pearson Correlation | −0.082 | −0.129 | 0.130 | 1 | 0.073 | 0.153 | 0.097 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.363 | 0.153 | 0.149 | 0.421 | 0.088 | 0.283 | ||||

| Q5 | Afternoon (16:00–21:00) | 125 | Pearson Correlation | −0.324 ** | −0.078 | −0.169 | 0.073 | 1 | 0.417 ** | 0.195 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.384 | 0.059 | 0.421 | 0.000 | 0.029 | ||||

| Q6 | Night (21:00–00:00) | 125 | Pearson Correlation | −0.285 ** | −0.137 | 0.057 | 0.153 | 0.417 ** | 1 | −0.034 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.127 | 0.526 | 0.088 | 0.000 | 0.710 | ||||

| Q7 | After Midnight (00:00–06:00) | 125 | Pearson Correlation | −0.318 ** | 0.103 | 0.091 | 0.097 | 0.195 * | −0.034 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.254 | 0.311 | 0.283 | 0.029 | 0.710 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicolaou, C.; Matsiola, M.; Dimoulas, C.A.; Kalliris, G. Discovering the Radio and Music Preferences of Generation Z: An Empirical Greek Case from and through the Internet. Journal. Media 2024, 5, 814-845. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5030053

Nicolaou C, Matsiola M, Dimoulas CA, Kalliris G. Discovering the Radio and Music Preferences of Generation Z: An Empirical Greek Case from and through the Internet. Journalism and Media. 2024; 5(3):814-845. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5030053

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicolaou, Constantinos, Maria Matsiola, Charalampos A. Dimoulas, and George Kalliris. 2024. "Discovering the Radio and Music Preferences of Generation Z: An Empirical Greek Case from and through the Internet" Journalism and Media 5, no. 3: 814-845. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5030053

APA StyleNicolaou, C., Matsiola, M., Dimoulas, C. A., & Kalliris, G. (2024). Discovering the Radio and Music Preferences of Generation Z: An Empirical Greek Case from and through the Internet. Journalism and Media, 5(3), 814-845. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5030053