Television Debates as a TV Typology: Continuities and Changes in Televised Political Competition—The Case of the 2023 Pre-Election Debates in Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Impact of TV Debates on Political Communication

3. X (Formerly Twitter) as a New Political Communication Tool

3.1. The Role of X (Twitter) in Election Periods

3.2. X (Twitter) as a Public Sphere in Pre-Election Periods

4. Methodology

5. Results

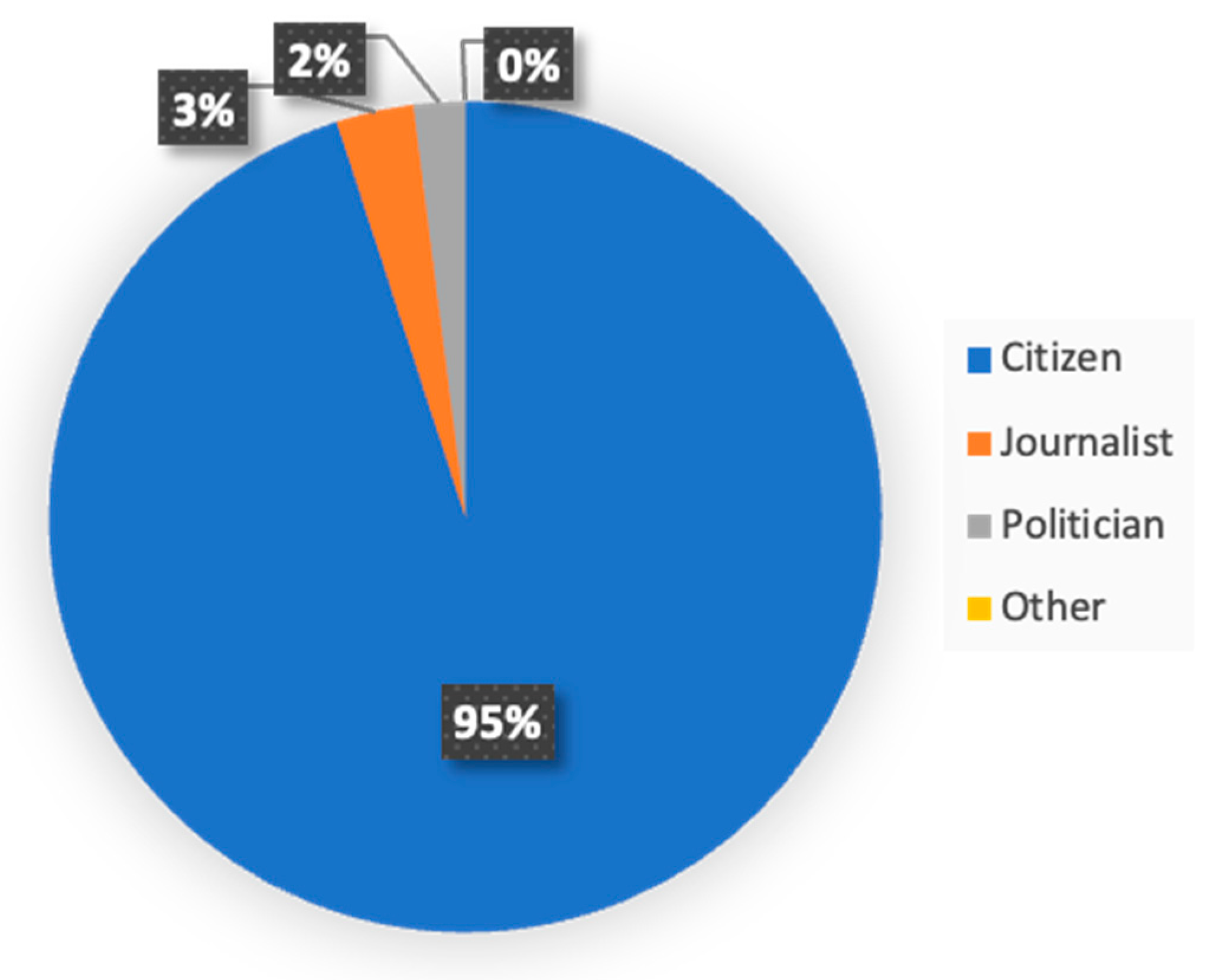

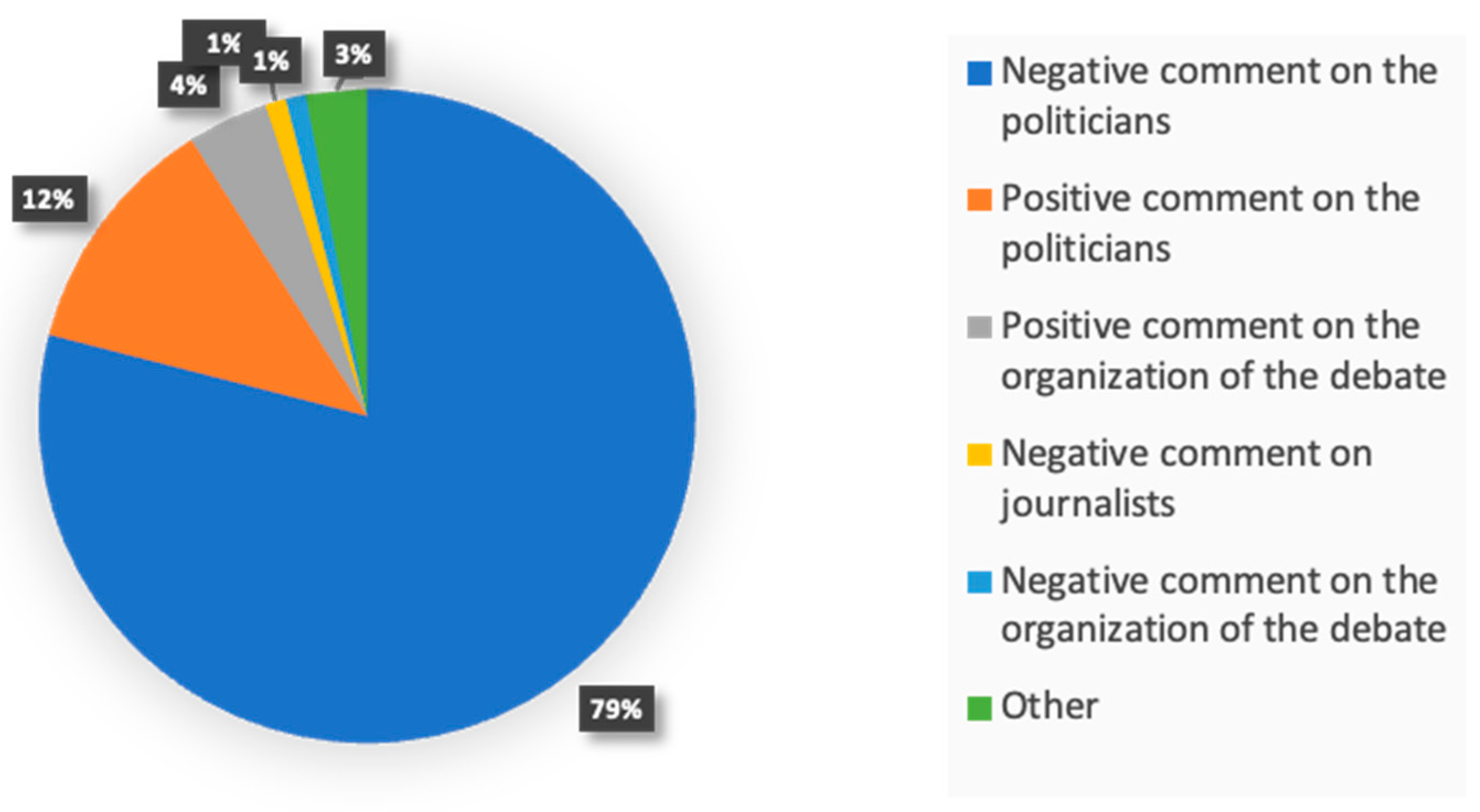

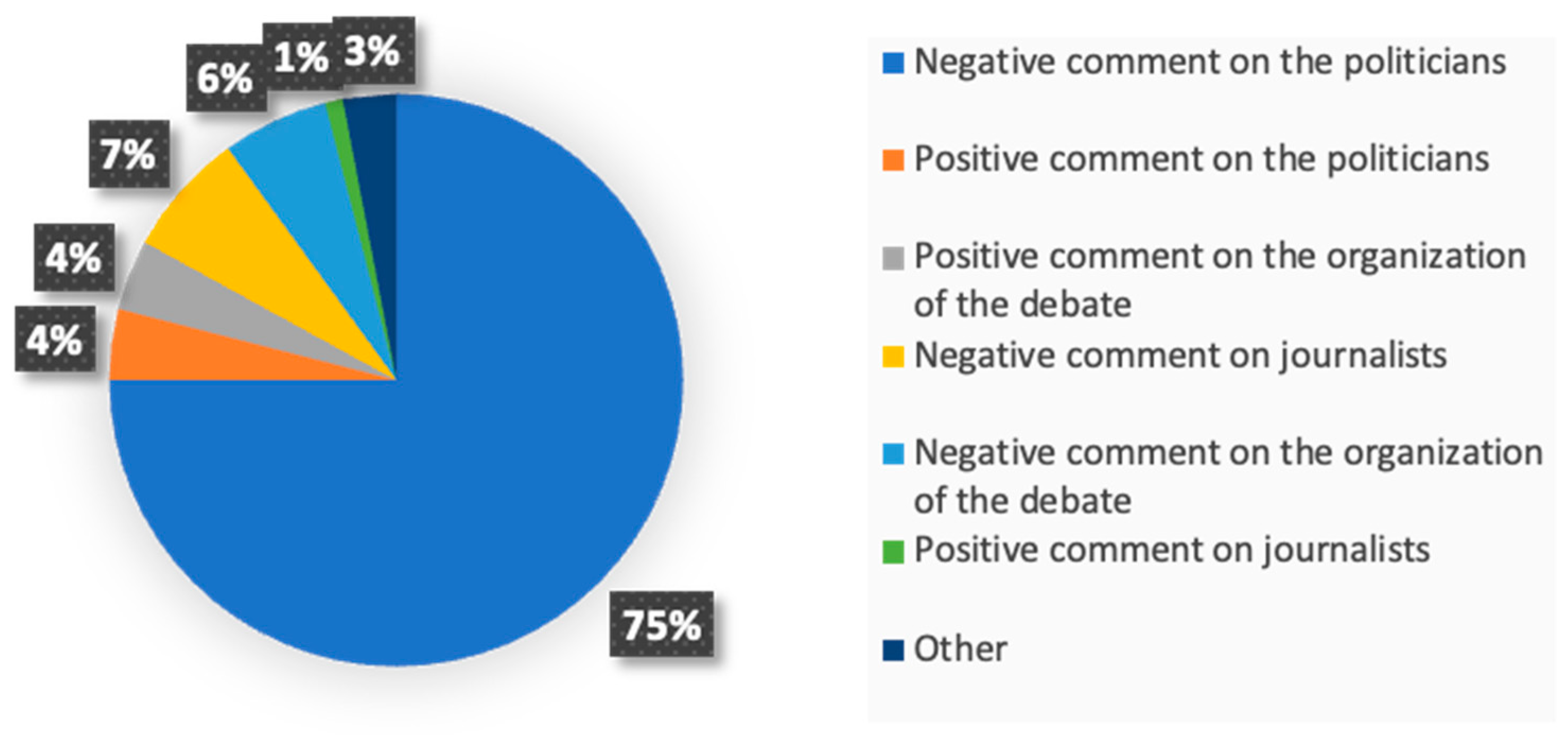

5.1. The Analysis of Conversations on X

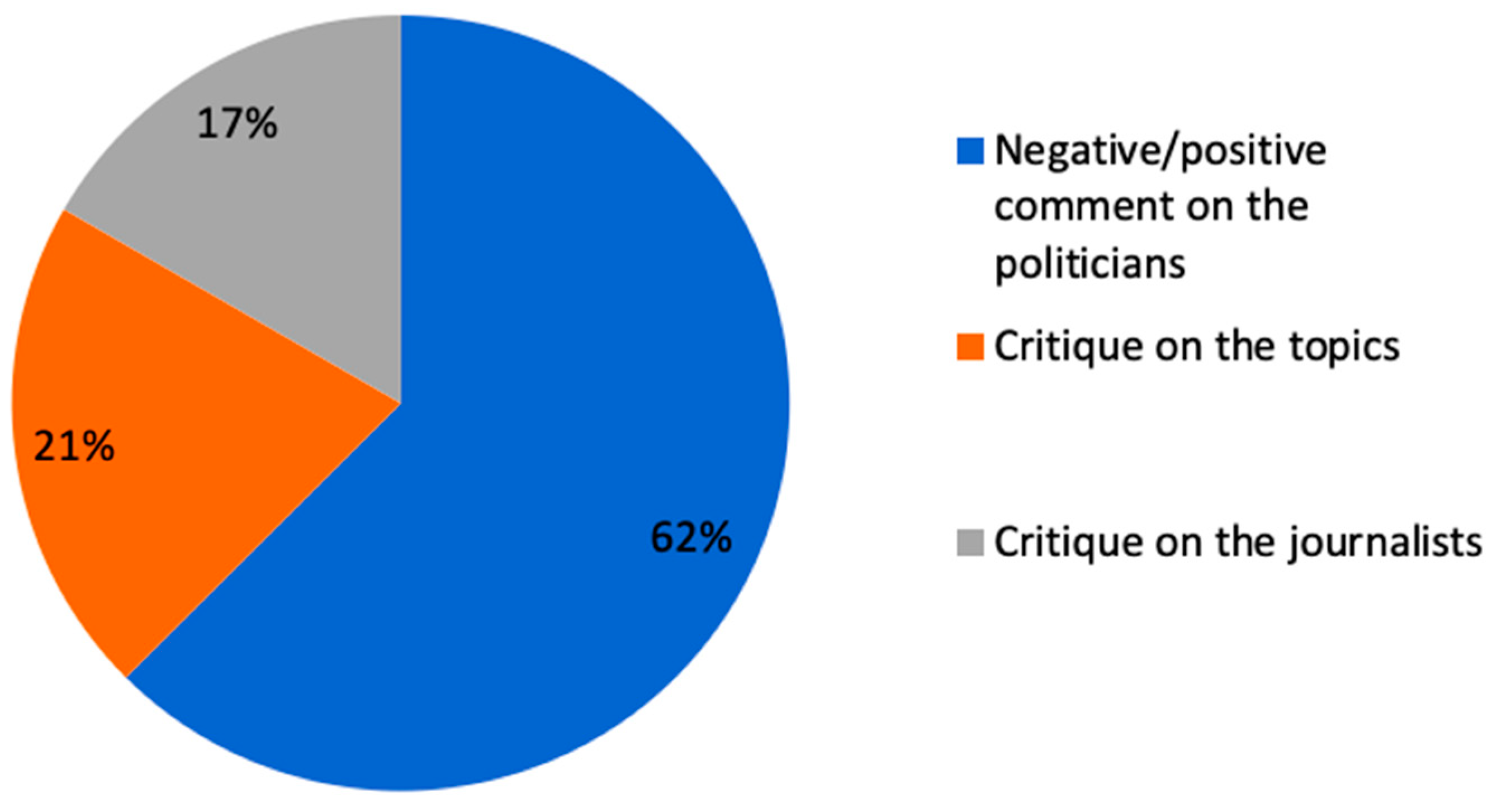

5.2. The Analysis of Journalists’ Articles in Online Media

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ausserhofer, Julian, and Axel Maireder. 2013. National politics on Twitter: Structures and topics of a networked public sphere. Information, Communication & Society 16: 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, William L., and Glenn J. Hansen. 2004. Presidential debate watching, issue knowledge, character evaluation, and vote choice. Human Communication Research 30: 121–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, William, Glenn Hansen, and Rebecca Verser. 2003. A meta-analysis of the effects of viewing U.S. presidential debates. Communication Monographs 70: 335–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumler, Jay, Stephen Coleman, and Christopher Birchall. 2017. Debating the Debates; How Voters Viewed the Question Time Special. London: Electoral Reform Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, Axel, and Jean Burgess. 2011. The use of Twitter hashtags in the formation of ad hoc publics. Presented at Proceedings of the 6th European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) General Conference, Reykjavik, Iceland, August 25–27; Colchester: The European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR), pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, Axel. 2017. Tweeting to save the furniture: The 2013 Australian election campaign on Twitter. Media International Australia 162: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffee, Steven. 1978. Presidential debates—are they helpful to voters? Communication Monographs 45: 330–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Christian. 2013. Wave-riding and hashtag-jumping: Twitter, minority ‘third parties’ and the 2012 US elections. Information, Communication & Society 16: 646–66. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, Robert, Jr., and Gary C. Woodward. 1990. Political communication in America. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Gioltzidou, Georgia. 2018. Journalism in the Era of Twitter—The Case of Greek Social Mobilisation. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Georgia-Gioltzidou/publication/378316427_Journalism_in_the_Era_of_Twitter_-The_case_of_Greek_Social_Mobilisation/links/65d48a2f1141586f3f5139f3/Journalism-in-the-Era-of-Twitter-The-case-of-Greek-Social-Mobilisation.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Gioltzidou, Georgia, Dimitra Mitka, Fotini Gioltzidou, Theodoros Chrysafis, Ifigeneia Mylona, and Dimitrios Amanatidis. 2024a. Adapting Traditional Media to the Social Media Culture: A Case Study of Greece. Journalism and Media 5: 485–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioltzidou, Georgia, Fotini Gioltzidou, and Theodoros Chrysafis. 2024b. Political Communication in the Digital Age: The Case of Social Media [H Πολιτική Επικοινωνία στην ψηφιακή εποχή: H περίπτωση των Κοινωνικών Μέσων]. Annual Greek-Speaking Scientific Conference of Communication Laboratories (Ετήσιο Ελληνόφωνο Επιστημονικό Συνέδριο Εργαστηρίων Επικοινωνίας) 2: 145–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, Doris. 1978. The media and the police. Policy Studies Journal 7: 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, Ryan S. 2014. How aid targets votes: The impact of electoral incentives on foreign aid distribution. World Politics 66: 293–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, Kathleen Hall, and David S. Birdsell. 1998. Presidential Debates: The Challenge of Creating an Informed Electorate. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, Kathleen Hall, and Christopher Adasiewicz. 2000. What can voters learn from election debates? In Televised Election Debates: International Perspectives. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens, Pascal, and Andreas Jungherr. 2015. The use of Twitter during the 2009 German national election. German Politics 24: 469–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgens, Pascal, Andreas Jungherr, and Harald Schoen. 2011. Small worlds with a difference: New gatekeepers and the filtering of political information on Twitter. Presented at Proceedings of the 3rd International Web Science Conference, Koblenz, Germany, June 15–17; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen, Rune, and Bernard Enjolras. 2016. Styles of social media campaigning and influence in a hybrid political communication system: Linking candidate survey data with Twitter data. The International Journal of Press/Politics 21: 338–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennamer, David. 1987. Debate viewing and debate discussion as predictors of campaign cognition. Journalism Quarterly 64: 114–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, Sidney. 2000. Televised Presidential Debates and Public Policy, 2nd ed. Mahwah: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Kruikemeier, Sanne. 2014. How political candidates use Twitter and the impact on votes. Computers in Human Behavior 34: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Kurt, and Gladys Engel Lang. 1962. Reaction of viewers. In The Great Debates: Background, Perspectives, Effects. Edited by Sidney Kraus. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 313–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lanoue, David. 1991. The “turning point” viewers’ reactions to the second 1988 presidential debate. American Politics Quarterly 19: 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanue, David. 1992. One that made a difference: Cognitive consistency, political knowledge, and the 1980 presidential debate. Public Opinion Quarterly 56: 168–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, Gilad, Erhardt Graeff, Mike Ananny, Devin Gaffney, and Ian Pearce. 2011. The Arab Spring/the revolutions were tweeted: Information flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. International Journal of Communication 5: 31. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Jürgen. 2023. What factors explain the broadcasting of televised election debates? Empirical evidence from Germany. European Journal of Communication 38: 272–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsaganis, Matthew, and Craig Weingarten. 2001. The 2000 U.S. presidential debate versus the 2000 Greek prime minister debate. American Behavioral Scientist 44: 2398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, Mitchell S., and Diana B. Carlin. 2004. Political campaign debates. In Handbook of Political Communication Research. London: Routledge, pp. 221–252. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, Jan W. 1978. Phoneme-tables and the functional principle. La linguistique 14: 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Papathanassopoulos, Stelios. 2000. Election Campaigning in the Television Age: The Case of Contemporary Greece. Political Communication 17: 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Perloff, Richard. 2014. The Dynamics of Political Communication: Media and Politics in a Digital Age. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Polsby, Nelson, Aaron Wildavsky, Steven Schier, and David Hopkins. 2012. Presidential Elections: Strategies and Structures of American Politics, 13th ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Reinemann, Carsten, and Jürgen Wilke. 2007. It’s the debates, stupid! How the introduction of televised debates changed the portrayal of chancellor candidates in the German press, 1949–2005. International Journal of Press/Politics 12: 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Self, John W. 2005. The first debate over the debates: How Kennedy and Nixon negotiated the 1960 Presidential debates. Presidential Studies Quarterly 35: 361–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siapera, Eugenia. 2017. Reclaiming citizenship in the post-democratic condition. Journal of Citizenship and Globalisation Studies 1: 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- The Racine Group. 2002. White Paper on Televised Political Campaign Debates. Argumentation and Advocacy 38: 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumasjan, Andranik, Timm Sprenger, Philipp Sandner, and Isabell Welpe. 2010. Predicting elections with twitter: What 140 characters reveal about political sentiment. Paper presented at the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Washington, DC, May 23–26, vol. 4, no. 1. pp. 178–85. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccari, Cristian. 2013. Digital Politics in Western Democracies: A Comparative Study. Baltimore, Maryland: JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vamvakas, Vasilis. 2006. Ekloges kai epikoinonia sti metapolitefsi.Politikotita kai theama. Athens: Savvalas. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, James B. 2003. Individual differences in television viewing motives. Personality and Individual Differences 35: 1427–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Content Categories | |

|---|---|

| Positive comments about the politicians participating in the debate | Negative comments about the politicians participating in the debate |

| Positive comments about the journalists participating in the debate | Negative comments about the journalists participating in the debate |

| Positive comments about the format of the debate | Negative comments about the format of the debate |

| Other | |

| Comments | |

|---|---|

| Max | 184 |

| Average | 3.585831 |

| Retweets | |

|---|---|

| Max | 397 |

| Average | 139.153005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bourchas, P.V.; Gioltzidou, G. Television Debates as a TV Typology: Continuities and Changes in Televised Political Competition—The Case of the 2023 Pre-Election Debates in Greece. Journal. Media 2024, 5, 799-813. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020052

Bourchas PV, Gioltzidou G. Television Debates as a TV Typology: Continuities and Changes in Televised Political Competition—The Case of the 2023 Pre-Election Debates in Greece. Journalism and Media. 2024; 5(2):799-813. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020052

Chicago/Turabian StyleBourchas, Panagiotis Vasileios, and Georgia Gioltzidou. 2024. "Television Debates as a TV Typology: Continuities and Changes in Televised Political Competition—The Case of the 2023 Pre-Election Debates in Greece" Journalism and Media 5, no. 2: 799-813. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020052

APA StyleBourchas, P. V., & Gioltzidou, G. (2024). Television Debates as a TV Typology: Continuities and Changes in Televised Political Competition—The Case of the 2023 Pre-Election Debates in Greece. Journalism and Media, 5(2), 799-813. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020052