Gatekeepers as Safekeepers—Mapping Audiences’ Attitudes towards News Media’s Editorial Oversight Functions during the COVID-19 Crisis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Legacy News Media as Gatekeepers in the Digital Environment

2.2. Gatekeeping as Editorial Oversight in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

3. Research Questions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. The Norwegian Case

4.2. Data

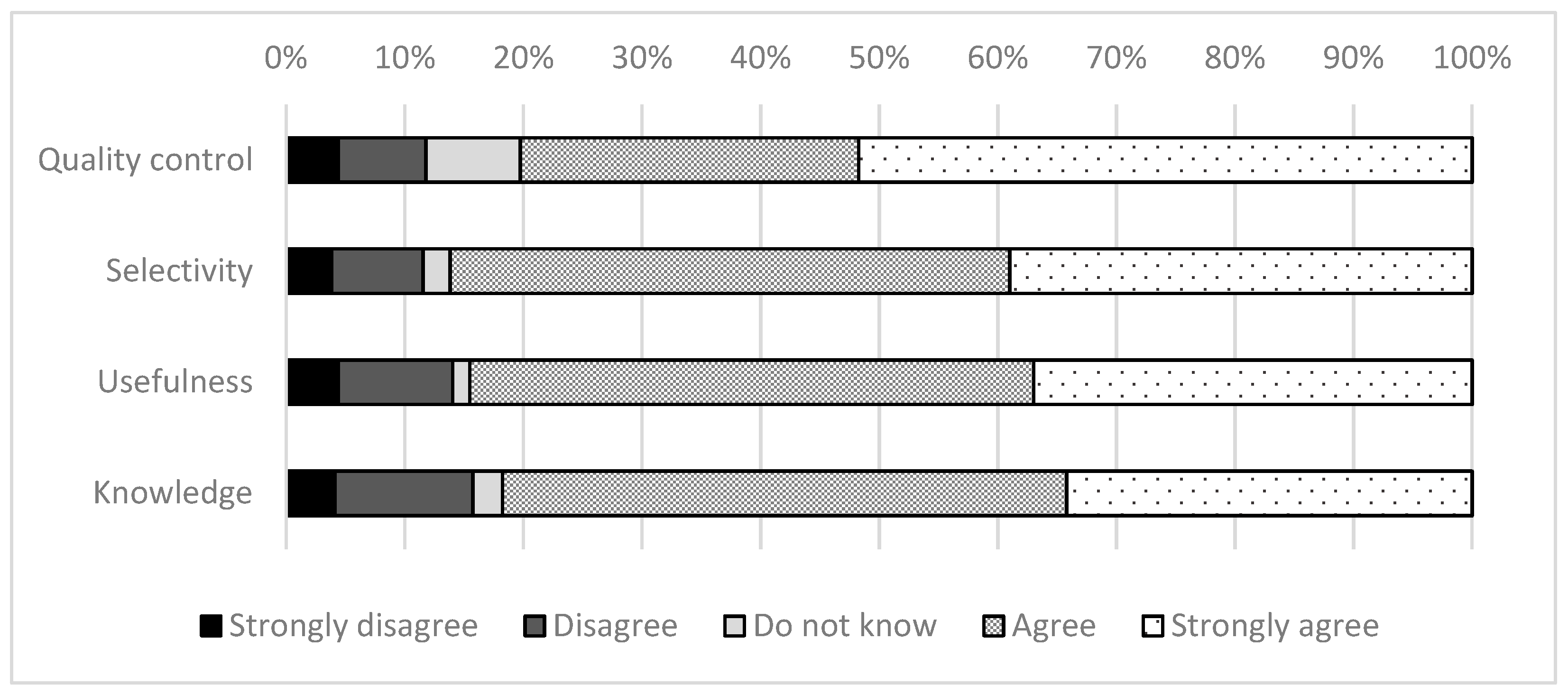

5. Findings

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, Shahmir H., Joshua Foreman, Yesim Tozan, Ariadna Capasso, Abbey M. Jones, and Ralph J. DiClemente. 2020. Trends and predictors of COVID-19 information sources and their relationship with knowledge and beliefs related to the pandemic: Nationwide cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 6: e21071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, Kim, Adam Shehata, and Dennis Andersson. 2021. Alternative News Orientation and Trust in Mainstream Media: A Longitudinal Audience Perspective. Digital Journalism, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, Mariella, Natali Helberger, and Mykola Makhortykh. 2021. Safeguarding the Journalistic DNA: Attitudes towards the Role of Professional Values in Algorithmic News Recommender Designs. Digital Journalism 9: 835–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthelsen, Rebecca, and Michael Hameleers. 2021. Meet Today’s Young News Users: An Exploration of How Young News Users Assess Which News Providers Are Worth Their While in Today’s High-Choice News Landscape. Digital Journalism 9: 619–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchett, Nicole. 2021. Participative Gatekeeping: The Intersection of News, Audience Data, Newsworkers, and Economics. Digital Journalism 9: 773–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöbaum, Bernd. 2014. Trust and Journalism in a Digital Environment. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Boberg, Svenja, Thorsten Quandt, Tim Schatto-Eckrodt, and Lena Frischlich. 2020. Pandemic populism: Facebook pages of alternative news media and the coronavirus crisis—A computational content analysis. arXiv arXiv:2004.02566. [Google Scholar]

- Bolin, Goran. 2017. Media Generations. Experience, Identity, and Mediatised Social Change. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bolin, Goran, and Eli Skogerbø. 2013. Age, generation and the media. Northern Lights: Film & Media Studies Yearbook 11: 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgman, Aengus, Eric Merkley, Peter John Loewen, Taylor Owen, Derek Ruths, Lisa Teichmann, and Oleg Zhilin. 2020. The causes and consequences of COVID-19 misperceptions: Understanding the role of news and social media. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bro, Peter, and Filip Wallberg. 2015. Gatekeeping in a digital era: Principles, practices and technological platforms. Journalism Practice 9: 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, Axel. 2018. Gatewatching and News Curation: Journalism, Social Media, and the Public Sphere. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Canavilhas, João, and Thaïs de Mendonça Jorge. 2022. Fake News Explosion in Portugal and Brazil the Pandemic and Journalists’ Testimonies on Disinformation. Journalism and Media 3: 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, Andreu. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on the media system. Communicative and democratic consequences of news consumption during the outbreak. El profesional de la Información 29: e290223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, Andrew. 2017. The Hybrid Media System. Politics and Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Tom, and Per Lægreid. 2020. Balancing governance capacity and legitimacy: How the Norwegian government handled the COVID-19 crisis as a high performer. Public Administration Review 80: 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruin, Kiki, Yael de Haan, Rens Vliegenthart, Sanne Kruikemeier, and Mark Boukes. 2021. News Avoidance during the COVID-19 Crisis: Understanding Information Overload. Digital Journalism 9: 1286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denman, Deanna C., Austin S. Baldwin, Andrea C. Betts, Amy McQueen, and Jasmin A. Tiro. 2018. Reducing “I don’t know” responses and missing survey data: Implications for measurement. Medical Decision Making 38: 673–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvestad, Eiri, Angela Phillips, and Mira Feuerstein. 2018. Can trust in traditional news media explain cross-national differences in news exposure of young people online? A comparative study of Israel, Norway and the United Kingdom. Digital Journalism 6: 216–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figenschou, Tine Ustad, and Karoline Andrea Ihlebæk. 2019. Challenging journalistic authority: Media criticism in far-right alternative media. Journalism Studies 20: 1221–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, Katherine. 2019. The biggest challenge facing journalism: A lack of trust. Journalism 20: 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futsæter, Knut-Arne. 2020. Aldri Har Mediebruken Endret Seg Så Dramatisk [News Consumption Has Never Changed So Quickly], Kampanje.com. Available online: https://kampanje.com/medier/2020/09/--aldri-har-mediebruken-endret-seg-sa-dramatisk/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Galan, Lucas, Jordan Osserman, Tim Parker, and Matthew Taylor. 2019. How Young People Consume News and the Implications for Mainstream Media. Cham. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-90281-4 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Gallotti, Riccardo, Francesco Valle, Nicola Castaldo, Pierluigi Sacco, and Manlio De Domenico. 2020. Assessing the risks of ‘infodemics’ in response to COVID-19 epidemics. Nature Human Behaviour 4: 1285–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, Lucas, and Federica Cherubini. 2016. The Rise of Fact-Checking Sites in Europe. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Gronke, Paul, and Timothy E. Cook. 2007. Disdaining the media: The American public’s changing attitudes toward the news. Political Communication 24: 259–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumpert, Gary, and Robert Cathcart. 1985. Media grammars, generations, and media gaps. Critical Studies in Media Communication 2: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinderyckx, François, and Tim P. Vos. 2016. Reformed gatekeeping. CM: Communication and Media 11: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowitz, Morris. 1975. Professional Models in Journalism: The Gatekeeper and the Advocate. Journalism Quarterly 52: 618–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeropoulos, Antonis, Jane Suiter, Linards Udris, and Mark Eisenegger. 2019. News media trust and news consumption: Factors related to trust in news in 35 countries. International Journal of Communication 13: 3672–93. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, Michael, Christer Clerwall, and Lars Nord. 2018. The public doesn’t miss the public. Views from the people: Why news by the people? Journalism 19: 577–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohring, Matthias, and Jörg Matthes. 2007. Trust in news media: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Communication Research 34: 231–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovach, Bill, and Tom Rosenstiel. 2021. The Elements of Journalism, Revised and Updated 4th Edition: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. New York: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Langfeldt Dahlback, Morten. 2021. Her er Ekkokammeret som gjør Alternative Medier til Virale Vinnere. [Here is the Echo Chamber which Turns Alternative Media into Viral Winners], faktisk.no. Available online: https://www.faktisk.no/artikler/0q4rw/her-er-ekkokammeret-som-gjor-alternative-medier-til-virale-vinnere (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Livio, Oren, and Jonathan Cohen. 2018. ‘Fool me once, shame on you’: Direct personal experience and media trust. Journalism 19: 684–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, Xosé, Carmen Costa-Sánchez, and Ángel Vizoso. 2021. Journalistic Fact-Checking of Information in Pandemic: Stakeholders, Hoaxes, and Strategies to Fight Disinformation during the COVID-19 Crisis in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthes, Jörg. 2006. The need for orientation towards news media: Revising and validating a classic concept. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 18: 422–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meijer, Irene Costera. 2013. Valuable journalism: A search for quality from the vantage point of the user. Journalism 14: 754–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, Claudia, Daniel Hallin, Luis Cárcamo, Rodrigo Alfaro, Daniel Jackson, María Luisa Humanes, Mireya Márquez-Ramírez, Jacques Mick, Cornelia Mothes, Christi I-Hsuan LIN, and et al. 2021. Sourcing pandemic news: A cross-national computational analysis of mainstream media coverage of COVID-19 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Digital Journalism 9: 1261–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Morgan. 2010. The rise of the knowledge broker. Science Communication 32: 118–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myllylahti, Merja. 2020. Paying attention to attention: A conceptual framework for studying news reader revenue models related to platforms. Digital Journalism 8: 567–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Napoli, Philip M. 2015. Social Media and the Public Interest: Governance of News Platforms in the Realm of Individual and Algorithmic Gatekeepers. Telecommunications Policy 39: 751–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2020. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, Craig T. Robertson, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2021. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis. 2021. Foreword in Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, Craig T. Robertson, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. In Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis, Richard Fletcher, J. Scott Brennen, Philip N. Howard, and Nic Newman. 2020. Navigating the ‘Infodemic’: How People in Six Countries Access and Rate News and Information about Coronavirus. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Media Authority. 2021. Mediemangfoldsregnskapet 2020. Available online: https://www.medietilsynet.no/globalassets/publikasjoner/2020/mediemangfoldsregnskapet-2020/210129-mediemangfold_bruksperspektiv_2021.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- OECD. 2022. Better Life Index Norway. Available online: https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/countries/norway/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Olsen, Ragnhild Kr, Bente Kalsnes, and Jens Barland. 2021. Do small streams make a big river? Detailing the diversification of revenue streams in newspapers’ transition to digital journalism businesses. Digital Journalism, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østbye, Helge. 2020. Norway-Media Landscape. Available online: https://medialandscapes.org/country/norway (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Pearson, George D.H., and Gerald M. Kosicki. 2017. How way-finding is challenging gatekeeping in the digital age. Journalism Studies 18: 1087–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, Mildred F., and Gregory P. Perreault. 2021. Journalists on COVID-19 Journalism: Communication Ecology of Pandemic Reporting. American Behavioral Scientist 65: 976–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, Mallory R. 2019. Biased gatekeepers? Partisan perceptions of media attention in the 2016 US presidential election. Journalism Studies 20: 2404–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posetti, Julie, and Kalina Bontcheva. 2020. Disinfodemic: Deciphering COVID-19 Disinformation. Policy Brief 1. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt, Thorsten, and Karin Wahl-Jorgensen. 2021. The Coronavirus Pandemic as a Critical Moment for Digital Journalism: Introduction to Special Issue: Covering COVID-19: The Coronavirus Pandemic as a Critical Moment for Digital Journalism. Digital Journalism 9: 1199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakariassen, Hilde, Jan Fredrik Hovden, and Hallvard Moe. 2017. Digital News Report Norway; Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available online: https://www.uib.no/sites/w3.uib.no/files/attachments/bruksmonstre_for_digitale_nyheter_uib.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Schranz, Mario, Jörg Schneider, and Mark Eisenegger. 2018. Media trust and media use. In Trust in Media and Journalism. Empirical Perspectives on Ethics, Norms, Impacts and Populism in Europe. Edited by Otto Kim and Andreas Köhler. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Schudson, Michael, and Chris Anderson. 2009. Objectivity, Professionalism, and Truth Seeking in Journalism. In Handbook of Journalism Studies. Edited by Wahl-Jorgensen Karin and Thomas Hanitzsch. New York: Routledge, pp. 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, Pamela J., and Timothy Vos. 2009. Gatekeeping Theory. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Jane B. 2006a. The socially responsible existentialist: A normative emphasis for journalists in a new media environment. Journalism Studies 7: 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, Jane B. 2006b. Stepping back from the gate: Online newspaper editors and the co-production of content in campaign 2004. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 83: 265–280. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Jane B. 2008. The journalist in the network: A shifting rationale for the gatekeeping role and the objectivity norm. Blanquerna School of Communication and International Relations 23: 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Jane B. 2014. User-generated visibility: Secondary gatekeeping in a shared media space. New Media & Society 16: 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Syvertsen, Trine, Ole Mjøs, Hallvard Moe, and Gunn Enli. 2014. The Media Welfare State: Nordic Media in the Digital Era. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tejedor, Santiago, Laura Cervi, Fernanda Tusa, Marta Portales, and Margarita Zabotina. 2020. Information on the COVID-19 pandemic in daily newspapers’ front pages: Case study of Spain and Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurman, Neil, Judith Moeller, Natali Helberger, and Damian Trilling. 2019. My friends, editors, algorithms, and I: Examining audience attitudes to news selection. Digital Journalism 7: 447–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsfati, Yariv. 2003. Media skepticism and climate of opinion perception. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 15: 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, Nikki. 2018. Re-thinking Trust in the News: A material approach through “Objects of Journalism”. Journalism Studies 19: 564–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aelst, Peter, Jesper Strömbäck, Toril Aalberg, Frank Esser, Claes De Vreese, Jörg Matthes, David Hopmann, Susana Salgado, Nicolas Hubé, Agnieszka Stępińska, and et al. 2017. Political communication in a high-choice media environment: A challenge for democracy? Annals of the International Communication Association 41: 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aelst, Peter, Fanni Toth, Laia Castro, Václav Štětka, Claes de Vreese, Toril Aalberg, Ana Sofia Cardenal, Nicoleta Corbu, Frank Esser, David Nicolas Hopmannh, and et al. 2021. Does a crisis change news habits? A comparative study of the effects of COVID-19 on news media use in 17 European countries. Digital Journalism 9: 1208–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, Tim P., and Ryan J. Thomas. 2019. The discursive (re) construction of journalism’s gatekeeping role. Journalism Practice 13: 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Julian. 2018. Modelling contemporary gatekeeping: The rise of individuals, algorithms and platforms in digital news dissemination. Digital Journalism 6: 274–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westlund, Oscar, and Marina Ghersetti. 2015. Modelling news media use: Positing and applying the GC/MC model to the analysis of media use in everyday life and crisis situations. Journalism Studies 16: 133–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, David Manning. 1950. The “gate keeper”: A case study in the selection of news. Journalism Quarterly 27: 383–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Bruce A., and Michael X. Delli Carpini. 2004. Monica and Bill all the time and everywhere: The collapse of gatekeeping and agenda setting in the new media environment. American Behavioral Scientist 47: 1208–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanovitzky, Itzhak, and Matthew S. Weber. 2019. News media as knowledge brokers in public policymaking processes. Communication Theory 29: 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarcadoolas, Christina, Andrew Pleasant, and David S. Greer. 2009. Advancing Health Literacy: A Framework for Understanding and Action. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Zarocostas, John. 2020. How to Fight an Infodemic. The Lancet 395: 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Erfei, Qiao Wu, Eileen M. Crimmins, and Jennifer A. Ailshire. 2020. Media trust and infection mitigating behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Global Health 5: e003323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–29 (M, SD) | 30–39 (M, SD) | 40–49 (M, SD) | 50–59 (M, SD) | 60+ (M, SD) | |

| Quality control | (4.14, 1.09) a | (4.08, 1.19) a | (4.17, 1.16) a | (4.11, 1.19) a | (4.26, 1.02) a |

| Selectivity | (3.97, 1.03) a | (3.81, 1.26) a | (3.94, 1.11) a | (4.26, 0.86) b | (4.5, 0.67) b |

| Usefulness | (3.96, 1.03) ac | (3.67, 1.30) b | (3.88, 1.18) ab | (4.19, 0.89) cd | (4.40, 0.83) d |

| Knowledge | (3.92, 1.03) a | (3.50, 1.34) | (3.85, 1.17) a | (4.09, 0.92) ab | (4.36, 0.82) b |

| Gender | Education | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | t-Test | Low | High | t-Test | |||||

| n | (M, SD) | n | (M, SD) | t (MD, SD) | n | (M, SD) | n | (M, SD) | t (MD, SD) | |

| Quality control | 508 | (4.03, 1.20) | 511 | (4.28, 1.02) | 989 (−0.25, 0.07) *** | 709 | (4.10, 1.14) | 310 | (4.27, 1.07) | 1017 (−0.17, 0.08) * |

| Selectivity | 506 | (4.03, 1.10) | 504 | (4.16, 0.94) | 981 (−0.13, 0.06) | 703 | (4.06, 1.05) | 307 | (4.19, 0.97) | 1008 (−0.13, 0.07) |

| Usefulness | 513 | (3.93, 1.18) | 511 | (4.12, 0.97) | 985 (−0.19, 0.07) ** | 713 | (3.96, 1.13) | 311 | (4.19, 0.93) | 1021 (−0.23, 0.07) ** |

| Knowledge | 513 | (3.88, 1.18) | 511 | (4.05, 1.00) | 1021 (−0.17, 0.07) * | 713 | (3.90, 1.12) | 311 | (4.10, 1.03) | 1021 (−0.20, 0.07) ** |

| Trust in Mainstream Media | Trust in Alternative Media | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRK | Aftenposten | VG | Resett.no and Document.no | |||||||||||||

| M | SD | CI for Mean (95%) | M | SD | CI for Mean (95%) | M | SD | CI for Mean (95%) | M | SD | CI for Mean (95%) | |||||

| M | SD | LB | UB | M | SD | LB | UB | M | SD | LB | UB | M | SD | LB | UB | |

| Quality control | 4.29 | 1.01 | 4.22 | 4.36 | 4.35 | 0.98 | 4.27 | 4.42 | 4.38 | 0.91 | 4.30 | 4.45 | 3.80 | 1.42 | 3.55 | 4.04 |

| Selectivity | 4.26 | 0.87 | 4.20 | 4.32 | 4.26 | 0.90 | 4.19 | 4.33 | 4.41 | 0.73 | 4.35 | 4.47 | 3.79 | 1.27 | 3.57 | 4.01 |

| Usefulness | 4.21 | 0.91 | 4.15 | 4.28 | 4.24 | 0.87 | 4.17 | 4.31 | 4.30 | 0.84 | 4.23 | 4.36 | 3.76 | 1.33 | 3.53 | 3.99 |

| Knowledge | 4.11 | 0.97 | 4.05 | 4.18 | 4.16 | 0.93 | 4.08 | 4.23 | 4.18 | 0.97 | 4.10 | 4.26 | 3.62 | 1.37 | 3.38 | 3.86 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olsen, R.K.; Solvoll, M.K.; Futsæter, K.-A. Gatekeepers as Safekeepers—Mapping Audiences’ Attitudes towards News Media’s Editorial Oversight Functions during the COVID-19 Crisis. Journal. Media 2022, 3, 182-197. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3010014

Olsen RK, Solvoll MK, Futsæter K-A. Gatekeepers as Safekeepers—Mapping Audiences’ Attitudes towards News Media’s Editorial Oversight Functions during the COVID-19 Crisis. Journalism and Media. 2022; 3(1):182-197. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlsen, Ragnhild Kristine, Mona Kristin Solvoll, and Knut-Arne Futsæter. 2022. "Gatekeepers as Safekeepers—Mapping Audiences’ Attitudes towards News Media’s Editorial Oversight Functions during the COVID-19 Crisis" Journalism and Media 3, no. 1: 182-197. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3010014

APA StyleOlsen, R. K., Solvoll, M. K., & Futsæter, K.-A. (2022). Gatekeepers as Safekeepers—Mapping Audiences’ Attitudes towards News Media’s Editorial Oversight Functions during the COVID-19 Crisis. Journalism and Media, 3(1), 182-197. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3010014