Abstract

Media work is a culture-making activity affecting the ways people understand the world and, therefore, workers in the media industries have a critical role in shaping collective memories, traditions, and belief systems. While studies regarding the characteristics impacting the nature of work in the media industries have significantly been increasing over the last years, the literature in this area remains highly fragmented. This paper begins to address that shortcoming by conducting an in-depth review of 36 scholarly papers in influential journals published from 2006 to 2020 to provide a comprehensive view of the literature and its approaches. This study elaborates on the concept of media work by organizing previous efforts into five subthemes, including commonalities, contested terrain, gendered profession, emerging practices, and influencing factors. Previous research has emphasized that media workers’ subjective experiences need to be explored further and more in-depth; however, if we wish to depict a more holistic but realistic picture, those experiences should be contextualized and thus linked with the specific organizational configurations and macro structures in which media work is embedded. The present review depicts how work in the media may take different meanings when addressing it through various theoretical frameworks. Our study can enrich future studies regarding the nature of media work by providing a fine-grained foundation in which researchers could understand how their given research problem(s) would be connected with the other issues that potentially impact their studies.

1. Introduction

Media organizations are operating in a very complex, technology-driven, and fast-changing environment in which they are supposed to wisely perform diverse tasks in a wide array of business, entertainment, and social areas (Lowe 2016; Murschetz et al. 2020). Moreover, they offer exceptional products that are essentially different from those of other industries (Picard 2005; Westlund and Lewis 2014). The exceptionality of media products also explains the uniqueness of media work, as leading scholars have highlighted (Hesmondhalgh and Baker 2013; Malmelin and Villi 2017b; Deuze 2007). Deuze and Lewis (2013) conceptualized media work as a wide range of professions engaged in producing cultures, symbols, and signs within the context of media and creative industries. These professions aim to contribute to the success of media products and are not limited to journalistic activities (Malmelin and Villi 2017b). Indeed, the life of workers in media organizations and that of people in society are tightly intertwined as people’s understanding of the world heavily relies on the content that media workers are creating for and delivering to them (Deuze 2014). Therefore, it can be argued that studying media workers’ professional lives may lead us to a better understanding of our own lives in the present era.

Capitalizing on previous research, we can conceive media work as a profession characterized by the following attributes, to name but a few: project-based (DeFillippi 2009), knowledge-based (Carlson 2019), creative (Malmelin and Virta 2016), innovative (Roshandel Arbatani et al. 2018; Omidi et al. 2020), emotional (Siapera 2019), relational (Baym 2015; Ehrlén and Villi 2020), reputational (Eigler and Azarpour 2020), entrepreneurial (Dal Zotto and Omidi 2020), autonomy-oriented (Von Rimscha 2015), precarious (De Peuter and Young 2019), gendered profession (Gopal 2019), and more in general atypical work (Elefante and Deuze 2012).

It is also worth noting that media work is highly affected by external changes such as regulatory and policy frameworks (Christopherson 2004; Alacovska and Gill 2019; Christopherson and van Jaarsveld 2005), technological transformations (Bartosova 2011; Lewis and Westlund 2015), and audience habits (Villi and Picard 2019; Chua and Westlund 2019; Barrios-Rubio 2021). This means that media work is by no means happening in a vacuum (Dickinson 2007), but the interesting point here is that—as Markova and McKay (2013) argued—these changes are shaping new forms of media work in such a way that workers may benefit from new opportunities (e.g., new ways of community building, more exciting workplaces, new applications of technologies for decision makings, etc.). At the same time though, media workers may experience more threats (e.g., heavier workloads, more stressful working environments, precariousness, etc.).

Previous research on media work has developed in different areas such as sociology, management, and journalism. While studies regarding the characteristics impacting the nature of work in the media industries have been significantly increasing over the last years, the literature in this area remains highly fragmented. Although some inspiring efforts have been made to connect the different ideas and perspectives on media work from a conceptual point of view (Malmelin and Villi 2017b; Deuze et al. 2020), a system-oriented and more inclusive approach for bringing dispersed empirical studies together is missing. Thus, by conducting a systematic review of the previous literature on media work, the present study seeks to understand the nature of media work in a more integrated way. We will explore and integrate the theoretical approaches, affecting factors, subjective experiences, and emerging challenges identified in past empirical studies.

We firmly believe that this effort can provide a fertile foundation for future labor-oriented studies in the media and creative industries and thanks to integrating the diverse trajectories characterizing this domain, it offers a polyvalent understanding of media work. The paper contributes to the burgeoning literature on the nature of media work. In particular, it provides an updated ground on which many interesting and unexplored questions can be posed to reach a more holistic view of media work, thereby helping future scholars to navigate among the diverse orientations existing in this field of research. From a practical point of view, it could help media workers to make sense of their profession more consciously across different contexts and industries and hopefully stimulate them to explore more meaningful ways of conducting work in the media. Reflections included in this paper may also enable media managers to proactively explore new ways of coping with the emerging challenges of the ever-increasing disruptions brought by digital and intelligent technologies.

To this end, the rest of the present paper is structured as follows. First, we present and discuss the theoretical background to explain some foundational studies in media work. Second, we specify the research method and materials that we used. Third, our findings by classifying them within five subthemes are explained and finally, we conclude our paper with our remarks for future research.

2. Theoretical Background

After decades of research on media content and audiences, researchers’ accelerating reflections on labor and work in the media industries have signaled a significant shift in media and communication studies that might be called a “cultural work turn” (Banks et al. 2013). To provide a theoretical context in this paper, we identify three dominant influential trends, although not exhaustive, that represent ground-breaking efforts in theorizing media work. To depict these three trends, we chose three scholarly works including two books and one article. The two books have been written by well-renowned scholars whose works have been quite influential—the considerable number of citations partially demonstrates this—in the growing literature on media work. The reason for choosing the third resource that appeared as an article is its conceptual approach: it reviewed the core literature on media work and paid exceptional attention to the emerging trend impacting the nature of media work. In the following, we address each of these studies separately and explain the critical elements that made them unavoidable resources on the nature of media work literature.

The first and foremost theoretical trend belongs to Deuze (2007), who systematically researched media workers’ subjective experiences in different careers such as journalism, advertising, public relations, and game development. It is fair to mark his influential book “Media Work” as a crucial milestone in turning attention toward labor in the media industries through an empirical investigation. Highly influenced by the postmodern thinker, Zygmunt Bauman, who characterized our society with its constant changing and melting life boundaries as liquid modernity (see Bauman 2013), Deuze (2007) introduced his conceptual framework that could be called “liquefied media work”. Embedded in a modern liquid society, media work is all about dealing with the ever-changing circumstances (see also Deuze 2011) related to four significant elements characterizing it: content, creativity, connectivity with audiences, and commercial imperatives (Deuze 2007). Deuze (2007) also showed that work in the media is highly dependent on the changes happening outside the workplace, such as technologies, markets, regulations, and policies. In all sorts of creative industries, the nature of media work is further defined by its function of creating cultures, as media work has a critical role in shaping collective memories, traditions, and belief systems (see Deuze 2007, 2016). Deuze (2007) finally envisaged how advancements in digital technologies would make it challenging to find a clear-cut definition for media work:

“I am arguing, however, what typifies media professions in the digital age is an increasing complexity and ongoing liquefaction of the boundaries between different fields, disciplines, practices, and categories that used to define what media work was.”(p. 112)

The second theoretical trend has been developed by Hesmondhalgh and Baker (2013), who proposed a conceptual model of media work that distinguishes between “good and bad models of media work”. Combining lessons harnessed from business studies, communication research, and the sociology of work, the two authors holistically investigated how media workers’ subjective experiences are embedded in political, cultural, economic, and organizational circumstances. In their insightful book “Creative Labour”, media work is conceived—in line with Deuze (2007)—as a culture-making activity affecting the ways people understand the world. Moreover, they contended that two influential groups could be distinguished in media work: (a) primarily creative personnel (e.g., writers, actors, musicians, etc.) and (b) technical workers (e.g., sound engineers, film editors, managers, etc.). In their conceptualization, tensions are crucial for understanding this type of work as media practitioners often struggle with commercial imperatives and the wish to keep their creative autonomy. In their model, Hesmondhalgh and Baker (2013) indicated that, in some specific situations, media workers might perceive their profession as either a promising source of meaningfulness or as a frustrating point in their professional lives. More specifically, they consider some features such as autonomy, involvement, sociality, self-esteem, self-realization, work-life balance, security, and contribution to the common good as characteristics of good media work. In contrast, other features, including being controlled by others, boredom, isolation, low self-esteem, missed self-realization, overwork, and instability, can lead to a flawed model of media work.

The last approach but not the least, is introduced by Malmelin and Villi (2017b), who drew attention toward new forms of media work that appeared in the digitalized ecosystem, a trend that might be called “emerging media work”. To propose a definition, they noted that media work is not a job that exclusively belongs or refers to journalists or content creators. Instead, it is related to all the professions contributing to the success of digital media products and services. Elaborating on the work of Deuze (2007), Malmelin and Villi (2017b) concretely showed how the roles of both media workers and managers have been transformed due to the dominant role of digital platforms in the media industries (see also Ruotsalainen and Villi 2018). In the current media landscape, media professionals are bound to improve their multitasking abilities, foster their commercial mindsets, and have a closer connection with their audiences (see also Villi et al. 2020; Villi and Matikainen 2015). Malmelin and Villi (2017b) also insisted that media work should not be understood within the frame of a value chain but of a value network in which critical actors such as audiences, media organizations, partners, and subcontractors operate in close collaboration with media workers.

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Research Design

The following research question leads our present review: “What are the main characteristics of work in the media industries?” To integrate the current state of knowledge regarding media work in an unbiased and replicable way, we employed a three-stage approach to our systematic literature review (SLR), which included planning, conducting, and reporting the review (Tranfield et al. 2003). We also attempted to follow the suggestions provided by the PRISMA statement concerning a rigorous and transparent review process (Moher et al. 2009). SLRs are valuable means to attain a state-of-the-art understanding of extant research on a particular topic, advancing future research by determining the current gaps and promising areas for further studies (Paul et al. 2021).

3.2. Search Strategy

As a starting point, we embraced “an understanding of media work that covers media content production, journalistic work, concept development and design, marketing and communication with audiences, as well as online services” (Malmelin and Villi 2017b). We used one of the major scientific databases, namely, Scopus, to identify and collect the previously published papers for our analysis. We separately conducted another round of hands-on research in well-renowned publishers’ websites such as Emerald, Wiley, Sage, ScienceDirect, and Taylor and Francis to strengthen our collecting process. Some of our search keywords included “media work” OR “media profession” OR “media labor” OR “media career” OR “work and media firms”.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Delineating which articles, among the searched ones, could have revealed a vital feature or an essential reality in media work, was somehow a problematic, if not daunting, task during the collecting process. One might argue that, although not wrongly, any research concerned with media organizations and media business would probably have some new insights to help readers in making sense of media work. As with the other rigorous literature reviews in the field, we sought to limit our scope and determine the protocols for including or excluding a potential article in our investigation. To this end, we agreed to consider those papers that explicitly studied the nature of, or the affecting factors in, work within the media industries. Thus, while addressing those papers and trying to make a decision, some questions arose in our minds such as: “Do the keywords in the paper include an explicit signifier such as media work, media labor, media career, etc.?” or “Is the paper proposing a clear question around the characteristics of media work?”. We also checked to what extent the searched papers were developed in line with the seminal theoretical trends highlighted in our theoretical background.

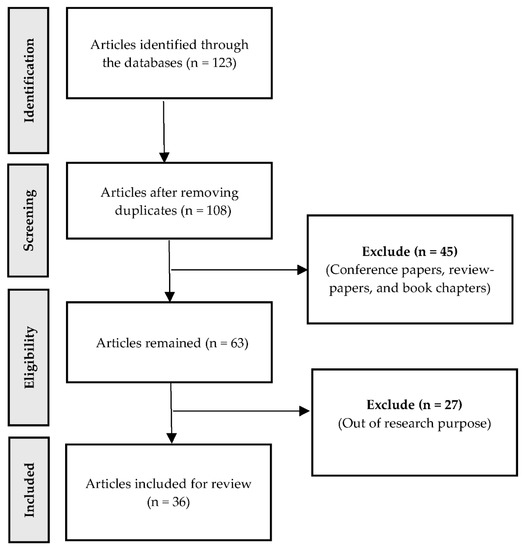

In line with this, by closely reading the titles, abstracts, and keywords in the first round of the literature search, and after removing the duplicates, 108 relevant scholarly documents were collected. We then excluded 45 papers (e.g., conference papers, book chapters, and non-empirical papers). The remaining 63 papers were closely studied, and 27 were further excluded as they fell outside of our research purpose and chosen definition of media work as declared above. Finally, 36 peer-reviewed papers, all indexed by Scopus and published between 2006 and 2020, were selected for conducting our literature review.

3.4. Data Analysis

To understand media work by looking at it from different angles, we conducted a thematic content analysis concerned with identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns regarding a particular subject (Braun and Clarke 2006). To do so, in the beginning, we heavily engaged in reading and, at the same time, taking notes from the final papers selected for our review. In the next phase, we began to identify common patterns and to generate some initial semantic codes indicating what seemed especially interesting about those papers. We then started to think about the existing relationships between our codes and notes to explore overarching subthemes that, in line with the aim of our paper, could potentially lead to a better understanding of media work. From the outset, we do not believe nor expect such subthemes to be sharply separated by clear-cut boundaries, nor that they would represent all dimensions that media work may entail. Instead, we encourage readers to proactively reflect on the possible inter-relationships between them. The present effort seeks to open up a fertile avenue for media work studies through multiple theoretical trends and conceptual lenses.

Figure 1 presents the review process employed by the current paper. After iteratively reviewing the explored subthemes, we finally organized the papers into the following five categories (see Table 1): (a) commonalities: this subtheme includes those studies seeking to analyze media workers’ subjective professional experiences in order to map common characteristics of media work; (b) contested terrain: the papers within this subtheme reflect a critical perspective and reveal the ways media workers may be exploited and alienated; (c) gendered profession: these studies show that gender inequalities in media work matter; (d) emerging practices: here papers explore new forms of media work in a digitized ecosystem; finally, in the subtheme (e) influencing external factors, studies identify the external factors affecting media work.

Figure 1.

The systematic article selection process based on the PRISMA flowchart.

Table 1.

Papers selected for this review.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Bibliometrics

Before diving into discussing our explored subthemes, we provide some bibliometric information to help future researchers better understand which countries and journals are primarily active in contributing to the development of the media work concept. Table 2 shows the corresponding author’s country of origin in the selected studies. Accordingly, among 13 nationalities that studied the nature of media work, the majority of reviewed papers were related to the USA researchers (n = 10), along with the UK (n = 7) and Finland (5). Considering the growing interest in this field of research over the past years, we expect to see new nationalities join this area soon.

Table 2.

Distribution of the papers based on the country of the corresponding author.

Table 3 indicates the journals in which the reviewed papers were published. As most papers reviewed in the present study were related to journalistic work, a substantial portion of articles appeared in the following three journals, namely, Journalism (n = 4), Digital Journalism (n = 3), and Journalism Practice (n = 3). These journals will probably remain some of the most popular targets for prospective researchers willing to contribute to the domain of media work. Out of the 23 journals listed in Table 3, 4 papers were published in sociology and culture-oriented journals, including Culture Unbound, European Journal of Cultural Studies, The Sociological Review, and Theory, Culture & Society. Two other papers were included in journals concerning educational and organizational studies, namely, Education + Training and Organization. The remaining papers in our review belong to journals (n = 17) exclusively focused on the areas of media and communication studies. This shows that media work has emerged as an issue across journals with multiple approaches to studying media, primarily in countries characterized by diversified and independent media systems, a broad journalistic culture, and where the professionalization of journalism is highly developed.

Table 3.

Distribution of the papers based on the name of journals.

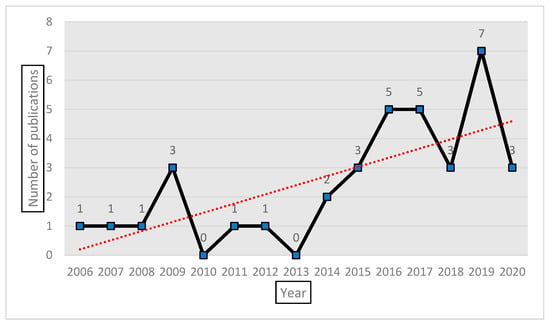

Figure 2 chronologically shows how research in media work has been growing within the same timeframe, from 2006 to 2020. This growing interest may indicate the need for new approaches to better understand the changing and complex nature of media work across different media industries, especially in the age of digital technologies. In particular, between 2006 and 2014, the pace of progress in publications was somehow gradual (n = 10). From 2014 to 2020, interestingly, we could observe considerable growth in the volume of published articles (n = 26).

Figure 2.

Distribution of papers based on year of publication.

4.2. Commonalities

This section addresses those studies concerned with identifying common features across different media industries that can help us understand what distinguishes work and, thus, professional lives in the media from work in other professional contexts.

By analyzing game developers’ and practitioners’ professional lives and identities, Deuze et al. (2007) empirically demonstrated that a professional identity could gradually be constructed through negotiating processes that, on an ongoing basis, try to balance workers’ desires, company ethos, and industry standards. According to this study, by sometimes accepting absurd conditions such as task overloads and long working hours, game developers are willing to compromise and sacrifice desired features to hopefully attain a position and become recognized as professional game developers in the industry. In another study, Martin and Deuze (2009) proposed a new way of thinking about work “independence” and “autonomy” as features characterizing professional lives in the context of the digital game industry. They contended that the meaning of independence should be understood within the frame of interplaying factors such as game producers, markets, technology, organizational structures, and audiences. Hence, “independence” can be explained as a multivalent concept with different meanings for the actors who operate in the game industry. For companies, as an example, it may mean a flexible way of structuring work in which workers can attain better results, while for developers, it may mean having the creative freedom to nurture their novel ideas alongside bearing the pressures imposed by the market. In a recent study, Creus et al. (2020) have further shown that media workers consider teamwork as a crucial competence to succeed in their profession in the game industry.

While the main body of literature in media work is concerned with current media workers’ professional lives, Ashton (2011, 2015) focused on prospective media workers’ unique experiences. In this regard, Ashton (2011) explored the anxieties that graduate media students face to increase their employability chances. As he argued, students make instrumental sense of “employability” as being professional. Hence, the concept of “professionalism” can be harnessed to investigate employability among prospective media workers. In another study, Ashton (2015) has further shown that novice media workers make sense of themselves as “runners” to enter film and television production. He insightfully pointed out that media students in higher education bear under-qualified tasks and unpaid work as a necessary step toward having a stable career in the future.

Many researchers have developed the idea that a significant aspect of media work is “creativity”; however, as Malmelin and Nivari-Lindström (2017) have shown, this concept entails different dimensions in the media industries. They maintained that, within journalism, a creative worker could be categorized as a person who benefits from a goal-driven personality, commercially oriented mind, and collaborative spirit. The other concept that may help our understanding of creative work in the media is “serendipity”, as Malmelin and Virta (2019) contended. According to their study, media workers can develop and increase their creative skills by learning about serendipitous situations within their organizations that may stimulate their creative behaviors and ideas. To this end, media workers should enhance their curiosity and personal engagement in the different situations within their organizations.

It is worth noting that not all kinds of media work happen within employment. Studying volunteering in the Eurovision Song Contest, Stiernstedt and Golovko (2019) have identified volunteering as a form of media work. They have indicated that “eventfulness” is a crucial feature that leads volunteers to perform an unpaid job. One of the critical implications of this study lies in the point that symbolic capital is an essential factor, which makes media workers feel remunerated, even if their work may be completely unpaid.

In order to make sense and grasp media workers’ professional lives, the studies mentioned above highlight common features such as “creativity”, “serendipity”, “autonomy”, and “teamwork”. They explain that when addressing a specific feature such as “autonomy” or “independence”, it is essential to consider how the given concept is being constructed by the different interplaying actors, including workers, managers, owners, audiences, and markets, among others. These studies further show how working in the media might have different meanings and values for prospective workers, such as media students who often make sense of themselves as “runners” in the industry and accept precarious working conditions to reach a position and be recognized as media professionals. We have also learned how a very particular feature such as “eventfulness” might lead volunteers to accept unpaid jobs and thus prompt organizers to develop free models of working in the media. A summary of the papers reviewed in this section is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Distribution of papers in the subtheme “professional lives”.

4.3. Contested Terrain

Inspired by Edwards’ (1979) book entitled “Contested Terrain”, we consider here the media workplace as the contested terrain in which different political and managerial forces stand against workers, who may finally perceive media work as a degraded profession. More clearly, the fundamental presumptions of the studies included in this subtheme concern antagonistic relations that arise between managers and workers. Some of the studies paid particular attention to the role of new technologies through which media managers seek to exploit workers to gain more output.

During the last decades, information and communications technologies (ICTs) had a tremendous impact on media work which has become a more technology-driven profession and has assumed various new forms; however, alongside the opportunities provided by technological advancements, some critical questions have arisen. Although not very optimistically, Liu (2006) considered how ICTs had brought a deskilling phenomenon to journalistic work. As highlighted in this study, ICTs have altered the journalistic profession and turned it into a trivialized reporting task, marginalizing journalists’ cognitive capabilities and devaluing their professional experience. In need of more tech-savvy staff, media managers were able to replace their experienced journalists with younger employees, thereby decreasing the labor costs of their organization. Moreover, under the guise of the rationalization of labor (see Bunce 2019), recent digital technologies and platforms have obfuscated the presence of managerial influence in journalism (Petre 2018). Taking a more balanced perspective, Kumar and Mohamed Haneef (2018) argued that digital technologies—mobile applications in this case—have not only deskilling effects but also upskilling implications. As far as the process of upskilling is concerned, digital applications have forced media workers to acquire new skills in order to be able to circulate data in novel ways. Equally, however, this trend may contain a deskilling force while transforming digital journalists from creators to content distributors. Having said that, there is essentially no devastative feature inside digital and smart technologies, rather, how media managers apply those technologies in their organizations can have quite problematic consequences for the quality of media work (Cohen 2019).

Alongside all the excitements and emotions that media workers perceive through their job, some conditions that characterize it, such as poor working relations, short-term project work, anxieties because of unstable jobs—to name but a few—have led some leading scholars to label media work as “precarious” (Hesmondhalgh and Baker 2008). Not surprisingly, one of the most common modes of working in media is freelancing. Deprived of, or being away from, a stable condition of employment, either due to personal intentions or structural deficits, media freelancers have been highly exploited by media firms, as Cohen (2012) indicated. More clearly, some media firms are exploiting freelancers by intensively using (a) their unpaid labor time and, thanks to rigid copyright regimes, (b) their intellectual property. Responding to these exploitative strategies, a growing number of independent media workers have started to perform their tasks in shared places, the so-called “co-working” spaces. De Peuter et al. (2017) argue that these spaces might be considered as “a stage for the performance of network sociality”. Following this perspective, freelancers could perceive co-working places as promising platforms for collectively acting to reclaim their rights. In a recent study, Salamon (2020) holds that economic instabilities in digital media industries have urged freelancers to see themselves as an individual business instead of unionized professional practitioners. As he has empirically shown, media freelancers are ideologically creating an emancipatory “e-lance” class within which they simultaneously sustain their entrepreneurial personalities and collective actions.

Another concept within the frame of critical evaluations and thus contested terrain of media work refers to a Marxist terminology, namely, “alienation”. Considering video game testing as a highly precarious job, Bulut (2015) has indicated that game testers are facing a process that might be called a “degradation of fun”—an expression borrowed from the Bravermanian term of “degradation of labor” in the labor process tradition (see Braverman 1998). Game testers are alienated from their purposive fun and forced to perceive their work as an instrumental way of play. In the case of journalists, Wu and Lambert (2016) have also addressed how market forces have driven Taiwanese reporters to feel alienated in their professional lives and that have hindered them from performing ethical practices. Putting this issue into a broader context, they argued that journalists’ financial pressures might even have critical implications for the future of press freedom.

Highly inspired by critical approaches in the area of social sciences, the above-reviewed papers signal a crucial shift within media workplaces that concerns how media managers exert power on workers for the sake of capital accumulation. These studies imply that, when studying the nature of media work, researchers need to consider the social and political forces to understand how the media work process is designed, organized, and managed. The role of digital technologies emerges as another critical issue deserving more attention to grasp the reasons and effects of their applications in organizing and managing media work. The other side of exerting control is workers’ resistance, which needs more attention to explore how media workers may respond to digital control both mentally and behaviorally. A summary of the papers reviewed in this section is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Distribution of papers in the subtheme “contested terrain”.

4.4. Gendered Profession

Over the years, we have witnessed different gender discrepancies across a wide array of industries worldwide in terms of salary, promotion, contracts, and work organization, to name but a few. This subtheme, in particular, argues that biased preferences exist toward a male-privileged point of view in media firms and holds that the professional challenges of media work are not equal for men and women. While only a few studies in the present review pertain to this subject, we have considered it an exclusive category to draw more attention to the gendered professions in the media industries. This section shows how gender issues play a critical role in recognizing what features might contribute to the perception of what media work is.

As O’Brien (2014) has maintained, women may leave their media organization due to gendered work cultures and structural impediments placed upon their wills to act freely and participate in the professional networks. In another study, Wang (2016) shows that female media workers have fragile job contracts, weak support from trade unions, and face sexist workplace cultures in their organizations. A 2018 report of the Center for Talent Innovation entitled “What #MeToo Means for Corporate America” states that 41% of women—compared with 22% of men—working within the media and entertainment industry in the USA have been sexually harassed by a colleague or boss at some point in their careers. The report further adds that across eight industry categories analyzed, the media and entertainment industries are the most concerned by the problem of sexual harassment. The media is a relationship-driven industry, where rewards in terms of money, visibility, and influence are controlled by a few gatekeepers who can easily abuse such power. Looking at gender inequalities in media work from a different perspective, Alacovska (2015) noted how gender-biased, masculine-oriented media cultures might create work anxieties for female travel writers since gender can mediate between professional experiences and practices. Considering this and other studies conducted by Alacovska (2017), one might argue that genres are of a gendering power as they implicitly govern and reproduce the ways professional identities and career aspirations are formed for women. It is worth mentioning that “the gendered genre boundaries, norms, and values have become stigmatization mechanisms that regulate and control how women writers forge professional identities, biographical self-definition, and aspirations, and go about sustaining their authorial careers” (Alacovska 2017, p. 392).

According to the reviewed papers in this section, one could argue that work in the media may have different meanings among non-male genders. Not only are there many objective factors that can make media work different for women, such as salaries and promotion, there also exist implicit forces such as that of “gendered genres” or the problem of sexual harassment that may induce numerous anxieties for female media workers and influence the way they perceive their work and future perspectives. These studies make the gender issue a crucial factor in understanding the multifaceted nature of media work. A summary of the papers reviewed in this section is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Distribution of papers reviewed in the subtheme “gendered profession”.

4.5. Emerging Practices

Media work is taking place in a fast-changing environment in which technological changes, economic, cultural, and political factors, audience tastes, and industry competition, to name just a few factors, have a considerable impact on how practices in the media are evolving. This subtheme thus discusses research about how the practices and required skills are changing and what new types of work are emerging in the media to face the new challenges imposed by a vast array of factors, such as the ones mentioned above. In this vein, Schmitz Weiss and Higgins Joyce (2009) noted how our globalized society, enabled by internet technologies, might have shortened the perceived distance between journalists and audiences. Journalists need to expand their skills and responsibilities as, in the digitalized media ecosystem, their job should be conceived of more as a multi-sided web production activity, thus requiring a constellation of different skills, rather than a sole and unique task.

Concerning this trend, Malmelin and Villi (2016) argued that media workers should consider the online audience community as a crucial source for fostering their function. As they contended, by understanding audiences deeper and more precisely and engaging with them at a more social and committed level—a practice spreading in media firms—media workers could bring new value into their organizations and adapt to the new realities of the current media landscapes. Much of the editorial teams’ work in a news organization is strategically devoted to maintaining a “feel-good” atmosphere within their audience communities (Malmelin and Villi 2017a). This proposition is even empirically tested and confirmed by another study conducted by Holton et al. (2016).

Malmelin and Virta (2016) mentioned that media professionals could better succeed in their job by enhancing some capabilities such as communication management, change management, and project management. Not only are these new skills necessary for succeeding in a highly competitive media industry, but they also represent the main motivational factor for media workers to perform their tasks more creatively. In a recent study, Agur (2019) highlights how new mobile applications have enabled media workers to acknowledge audiences’ agency, thereby building a space for fostering co-creation in journalism.

As the above studies suggested, media work is continuously changing. While much attention has been paid to the way media workers can keep up with the new realities in the media industries, we also need to consider that the pace of change within media work is considerably fast. Thus, great importance needs to be placed on the capability of media workers and firms to track new trends in technology, audience tastes, and the like that would induce other revolutionary changes in the required skills. The studies we discussed showed what skills and practices need to receive more attention from media workers and managers in the digital age; however, they did not reveal much about what types of practices should preferably be divested. Moreover, we are witnessing a massive move toward multi-tasking in media work; hence, research is needed to understand whether and how managers, media owners, or workers could gain more from such transformational trends. A summary of the papers that have been reviewed in this section is presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Distribution of papers in the subtheme “emerging practices”.

4.6. Influencing Factors

Various organizational and external factors affect how media professionals perceive and thus perform their work. This subtheme involves research to identify and explore those influencing factors. In this relation, Witschge and Nygren (2009) noted that technology and economic transformations are changing the established standards with which the journalistic labor was once defined. They have empirically shown that, because of the dominant role of digital media platforms in the media industries and the empowerment of audiences to disseminate content actively, journalism is undergoing a de-professionalization process mainly exacerbated by market pressures. Another study conducted by Evans (2014) indicated that digital technologies forced media workers to re-evaluate their perception of the profession’s boundaries. Concerning the impact of digital and smart technologies on the nature of media work, there are other studies regarding the effects of social media on the personal branding practices of media workers (Molyneux et al. 2019), or how automation is changing the core values of journalism (Milosavljević and Vobič 2019).

The affecting factors are by no means limited to technological transformations. Indeed, some other items have also been studied. Stiernstedt (2017), for example, addressed how changes at the policy level might have critical consequences for shaping work in the media industries. To understand the escalating precariousness and de-professionalization of work in the media industry, he argued that the role of the economic situation and technological transformation must also be interpreted by acknowledging the effects of policy changes and regulative frameworks. Moreover, Sherwood and O’Donnell (2018) showed how losing jobs because of unfavorable employment conditions and lacking a robust institutional background in their profession would alter media practitioners’ perception of their professional identities in the long run. It is worth noting that media workers’ subjective experiences about the nature of their job are pretty fluid and can change over time, i.e., it is a transformative process being rooted in the society’s broader context (Wallis et al. 2020).

The most crucial factor discussed in the above studies has been digital technologies’ growing role in changing the media profession; however, the consequences vary, from exacerbating the market pressures and the rate of de-professionalization in journalistic work to providing novel opportunities such as the possibility for media workers to build a personal brand. We by no means consider new technologies as definite forces shaping the evolution path of media work, but rather, we conceive them as the reflections of social, economic, and political relations existing in each society. A critical implication of such insight could be suggesting that future researchers interpret the effects of new technologies in the light of macro frameworks that shape how these technologies are conceived and employed. It is also worth mentioning that the media workers’ perceptions of their profession could be changed over time. Therefore, a favorable perception of work in the media might be induced and increased among workers in the long run by developing institutional support (e.g., media labor unions) and enhancing employment conditions offered by media organizations. A summary of the papers reviewed in this section is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Distribution of papers in the subtheme “influencing factors”.

5. Conclusions

The present paper sought to integrate theoretical approaches, subjective experiences, structural challenges, and influencing factors that characterize work in the media industries. While some essential features such as emotion, passion, and creativity in media work have seemingly remained intact, we contend that media work is still being shaped and transformed, primarily due to the fast evolution of digital and smart technologies and their undeniable influence on work processes. Relying on a comprehensive review of relevant previous literature, we have shown that media work has been and still is facing both opportunities and threats in its evolution path. We here strongly argue that technologies have no truly devastative orientations in their very natures. Instead, some specific political, social, and managerial decisions leading to their adoption and implementation can negatively influence media work and place it into a contested terrain. Thus, contrary to a binary point of view toward media work, such as that of the good and bad model of work in the media proposing negative and positive dualities in the definition of media work (Hesmondhalgh and Baker 2013), the present paper supports the adoption of a fluid point of view (Deuze 2007; Malmelin and Villi 2017b), highlighting the atypical nature of media work (Deuze et al. 2020). We need to consider that the boundaries previously used to define what media work was are quite blurred due to the fast-changing society and lifestyle in our present world (Bauman 2013), which is highly prompted by digital technologies.

We tried here to show how work in the media may take different meanings when addressing it through various theoretical frameworks. Our study can enrich future studies regarding the nature of media work by providing a fine-grained foundation in which researchers could understand how their given research problem(s) would be connected with the other issues that potentially impact their studies. The present review informs future scholars by indicating its significant contributions in four ways.

First, media work presents some continuities, such as the reasons that motivate individuals to work in the media (e.g., creativity, passion, autonomy, etc.); however, even these seemingly fixed aspirations are socially being (re)constructed by different players in media workplaces over time. This viewpoint helps us research on how various actors shape the nature of work in the media, an issue that could be addressed through a techno-social framework (Lewis and Westlund 2015). Second, media workplaces include people whose interests are not always harmonious. Power is not even equally distributed between actors, managerial strategies are not perpetually directed at making the workplace better for its people, and new technologies are not always employed to bolster workers’ capabilities. Furthermore, gender is not a neutral concept in making sense of the nature of work in the media. This approach urges us to be oriented toward and to more intensively address ethical issues in media organizations and practices (Picard 2021). Third, due to the highly technology-driven nature of media work, the borders and features defining what media work is are being fluctuated and blurred at a considerable pace. Therefore, to define media work, we need to recognize and consider the emerging and forgotten practices and skills challenging our perception of work in the media industries. This viewpoint leads us to see media work as an ongoing process where change is the most predominant feature of the media profession (Malmelin and Villi 2017b). Finally, media work is not just a workplace-related concept. Instead, it is highly interconnected with other issues outside media organizations, such as technological advancements and policy reforms. This point of view encourages us to employ macro frameworks to recognize the influencing factors shaping the ways media organizations operate in general and of workers inside these organizations in particular (Küng 2017).

5.1. Future Directions

By reviewing and integrating the previous literature on media work into five interrelated subthemes, the current paper has analyzed the current state of knowledge in this area. While the majority of past studies focused on the positive and negative effects of digital technologies on the nature of media work, we still need more research to understand how emerging smart technologies (e.g., artificial intelligence) could complete, if not threaten, the work processes within media organizations, and how media workers are feeling about their affordances and reacting as a consequence. Moreover, as the current platform-driven ecosystem is ever penetrating the media industries, it might be interesting to address the extent to which these platforms have influenced the core values of different types of media work such as journalism, filmmaking, or broadcasting. In addition, we urge future researchers to study how the nature of work is being shaped among prospective professionals (i.e., media students). A further subject to explore might be that of discovering how gender issues—especially those concerning underrepresented genders in the LGBTQ community—play a role in the experience of media work, and finally, how macro changes such as institutional support and employment regulations could affect the media workers’ perception of their profession in the long run.

From a managerial and sociological point of view, specifically, future researchers can also employ the labor process theory (Braverman 1998; Burawoy 1982; Edwards 1979) to explore the (structured) antagonisms that exist, if any, between workers and managers. This theory places capital accumulation as the central concern of modern corporations and shows how this orientation steers the ways workers are managed, directed, and evaluated (Gandini 2019). Considering this issue, one might argue that if the appetite for capital accumulation prevails, media workers cannot experience a meaningful job as they should primarily serve the employers’ monetary interests. In doing so, the prospective researchers can critically discover, more holistically than before, the various forces (at micro, meso, and macro levels) shaping media workplaces in different contexts and countries with particular effects. Keeping this approach at the center for studying the nature of media work, future researchers could elaborate on a humanistic model to manage people in media organizations called “socially responsible human resource management” or SRHRM (Omidi and Dal Zotto 2022). The SRHRM discourse encourages organizations to adopt an ethical approach toward their employees not due to their instrumental values for the organizational aims but for providing a context in which individuals can flourish, thereby contributing to societal wellbeing in the long run. This concept has been growing in other fields, while we can barely find a robust study that brings novel insights into the SRHRM debate concerning work in the media. This approach can be completed by a craft-based perspective that seeks to study work processes by setting human engagement and autonomy as the main concerns for organizing work (Kroezen et al. 2021). We encourage future researchers to study how digital technologies and platforms might hinder or enhance craft approaches to the organization of work in the media industries. We believe these suggestions could steer future studies to bring new insights for enabling and developing meaningful media work in the current digital ecosystem.

From a methodological point of view, it is worth noting that out of 36 papers reviewed in this study, 33 articles employed qualitative methodologies. While this shows how this area has been unexplored in academia, the dearth of quantitative studies in the future might hinder the constructive dialogue between different paradigms and methodologies. Therefore, we encourage future researchers familiar with quantitative techniques to validate the concepts emerging from qualitative articles and address their generalizability for other media industries and contexts. We also highlight the importance of comparative studies, still scant in the previous literature, for bringing novel insights concerning the different meanings of work across societies and media industries. For instance, future researchers can address and compare how journalists in a developed and an underrepresented country give meaning to their jobs. This way, the factors that play a critical role in shaping the nature of media work could more clearly be understood.

Generally speaking, more efforts are needed to map and track how media work is evolving. Future researchers are encouraged to embrace other theoretical frameworks, harnessed from a wide array of disciplines such as sociology, management, psychology, philosophy, etc., to reflect on the nature of media work from different angles and across various media industries. Due to the complicated nature of work in the media, interested scholars are highly advised to develop their research by possibly collaborating in interdisciplinary projects. Previous research has correctly emphasized that media workers’ subjective experiences need to be explored further and more in-depth; however, we insist that if we wish to depict a more holistic but realistic picture, those experiences should be contextualized and thus linked with the specific organizational configurations and macro structures in which media work is embedded. To this end, every subtheme of media work clarified in the present study could provide a possible foundation on which a prospective researcher might pose some interesting and creative questions to initiate a novel yet critical analysis.

5.2. Practical Implications

Among the most critical implications of digital technologies, we can underline their soft power on defining who can be a media worker and who cannot (Panagiotidis and Veglis 2020). More clearly, by transforming the skills required to be employed within a media organization, these new technologies might create a situation—that would even be accepted as an uncontested truth among professionals—where simply tech-savvy persons or digital traffic-boosters are recruited and selected (see González-Tosat and Sádaba-Chalezquer 2021). This trend may potentially lead to a process of what might be called “smart exclusion”, with far more problematic consequences especially for those jobs in close connection with the development of diversified perspectives in a democratic society, namely, journalism. Such smart exclusion can have negative impacts on the degree of diversity within work environments, but it might also change the very nature of the journalistic profession transforming it from a content creation to a distribution and marketing-oriented activity. To counteract this potential threat, media managers might reflect more consciously about—and thereby transform their internal organizational processes for—the high ends which they are supposedly serving (e.g., contributing to an inclusive and democratic world) rather than merely revolving around the imperatives of business models and rational modes of operational efficiency in a highly digitalized ecosystem (e.g., traffic boosting).

The other practical implication of this study might pertain to the role of digital platforms in shaping the ways media workers create content and the extent to which these platforms might increase or decrease media workers’ autonomy in their professions. Within journalism, for instance, previous literature shows that social media editors considerably attempt to conform to the logic of Facebook’s algorithm that might push journalists to create only particular types of content (Lischka 2021). When news organizations seek to follow the logic of these platforms, they are led to topics that increase media coverage and are guided regarding how they should perform the necessary process for creating content. We do not argue that the logic of digital platforms should be ignored; however, we insist that media managers need to employ those platforms to help their professionals find an individualized style to perform their work and to feel autonomy in their work lives rather than being a servant to feed these platforms that do not always aim to enrich democratic societies.

5.3. Research Limitations

As with other literature reviews, we faced some limitations. As mentioned in the method section, the first limitation concerns the complexities in determining the potential papers that could significantly bring novel insights into the nature of work in the media industries. While we explained our inclusion criteria, it is arguable that considering other criteria and keywords could have added other studies; however, we mainly sought to depict a holistic map of media work across different studies. Each subtheme that appeared in the results section can inform future systematic reviews to deeply dive into those concepts and provide a detailed overview within each of the explored subthemes. The second limitation is that we are doubtful that the papers we reviewed in this study could provide a comprehensive interpretation of media work as most of the considered studies came from developed countries; however, this doubt can stimulate future studies to consider conceptualizing media work by focusing on non-western countries. Finally, since we focused more on the commonalities in media work across different studies, the present review could barely inform readers concerning the peculiarities within each specific media industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O. and C.D.Z.; methodology, A.O.; investigation, A.O. and C.D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O. and C.D.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.D.Z. and R.G.P.; visualization, A.O.; supervision, C.D.Z. and R.G.P.; project administration, C.D.Z.; funding acquisition, C.D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agur, Colin. 2019. Insularized Connectedness: Mobile Chat Applications and News Production. Media and Communication 7: 179–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alacovska, Ana, and Rosalind Gill. 2019. De-Westernizing Creative Labour Studies: The Informality of Creative Work from an Ex-Centric Perspective. International Journal of Cultural Studies 22: 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alacovska, Ana. 2015. Genre Anxiety: Women Travel Writers’ Experience of Work. The Sociological Review 63: 128–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alacovska, Ana. 2017. The Gendering Power of Genres: How Female Scandinavian Crime Fiction Writers Experience Professional Authorship. Organization 24: 377–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, Daniel. 2011. Media Work and the Creative Industries. Education + Training 53: 546–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, Daniel. 2015. Making Media Workers. Television & New Media 16: 275–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Mark, Rosalind Gill, and Stephanie Taylor. 2013. Introduction: Cultural Work, Time and Trajectory. In Theorizing Cultural Work: Labour, Continuity and Change in the Cultural and Creative Industries. Edited by Mark Banks, Rosalind Gill and Stephanie Taylor. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios-Rubio, Andrés. 2021. From the Antenna to the Display Devices: Transformation of the Colombian Radio Industry. Journalism and Media 2: 208–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosova, Daniela. 2011. The Future of the Media Professions: Current Issues in Media Management Practice. International Journal on Media Management 13: 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2013. Liquid Modernity. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Baym, Nancy K. 2015. Connect With Your Audience! The Relational Labor of Connection. The Communication Review 18: 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, Harry. 1998. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York: Monthly Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, Ergin. 2015. Playboring in the Tester Pit. Television & New Media 16: 240–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, Mel. 2019. Management and Resistance in the Digital Newsroom. Journalism 20: 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burawoy, Michael. 1982. Manufacturing Consent: Changes in the Labor Process under Monopoly Capitalism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, Matt. 2019. News Algorithms, Photojournalism and the Assumption of Mechanical Objectivity in Journalism. Digital Journalism 7: 1117–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopherson, Susan, and Danielle van Jaarsveld. 2005. New Media after the Dot.Com Bust. International Journal of Cultural Policy 11: 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopherson, Susan. 2004. The Divergent Worlds of New Media: How Policy Shapes Work in the Creative Economy1. Review of Policy Research 21: 543–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, Sherwin, and Oscar Westlund. 2019. Audience-Centric Engagement, Collaboration Culture and Platform Counterbalancing: A Longitudinal Study of Ongoing Sensemaking of Emerging Technologies. Media and Communication 7: 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Nicole S. 2012. Cultural Work as a Site of Struggle: Freelancers and Exploitation. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 10: 141–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Nicole S. 2019. At Work in the Digital Newsroom. Digital Journalism 7: 571–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creus, Amalia, Judith Clares-Gavilán, and Jordi Sánchez-Navarro. 2020. What’s Your Game? Passion and Precariousness in the Digital Game Industry from a Gameworker’s Perspective. Creative Industries Journal 13: 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Zotto, Cinzia, and Afshin Omidi. 2020. Platformization of Media Entrepreneurship: A Conceptual Development. Nordic Journal of Media Management 1: 209–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Peuter, Greig, and Chris J. Young. 2019. Contested Formations of Digital Game Labor. Television & New Media 20: 747–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Peuter, Greig, Nicole S. Cohen, and Francesca Saraco. 2017. The Ambivalence of Coworking: On the Politics of an Emerging Work Practice. European Journal of Cultural Studies 20: 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFillippi, Robert. 2009. Dilemmas of Project-Based Media Work: Contexts and Choices. Journal of Media Business Studies 6: 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuze, Mark, Chase Bowen Martin, and Christian Allen. 2007. The Professional Identity of Gameworkers. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 13: 335–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuze, Mark, Johana Kotišová, Gemma Newlands, and Erwin Van’t Hof. 2020. Toward a Theory of Atypical Media Work and Social Hope. Artha Journal of Social Sciences 19: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuze, Mark, and Nicky Lewis. 2013. Professional Identity and Media Work. In Theorizing Cultural Work: Labour, Continuity and Change in the Cultural and Creative Industries. Edited by Mark Banks, Rosalind Gill and Stephanie Taylor. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 161–74. [Google Scholar]

- Deuze, Mark. 2007. Media Work. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deuze, Mark. 2011. Media Life. Media, Culture & Society 33: 137–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuze, Mark. 2014. Work in the Media. Media Industries Journal 1: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuze, Mark. 2016. Managing Media Workers. In Managing Media Firms and Industries. Edited by Gregory Ferrell Lowe and Charles Brown. Cham: Springer, pp. 329–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, Roger. 2007. Accomplishing Journalism: Towards a Revived Sociology of a Media Occupation. Cultural Sociology 1: 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Richard. 1979. Contested Terrain. London: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlén, Veera, and Mikko Villi. 2020. ‘I Shared the Joy’: Sport-Related Social Support and Communality on Instagram. Visual Studies 35: 260–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigler, Joachim, and Samaneh Azarpour. 2020. Reputation Management for Creative Workers in the Media Industry. Journal of Media Business Studies 17: 261–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elefante, Phoebe Harris, and Mark Deuze. 2012. Media Work, Career Management, and Professional Identity: Living Labour Precarity. Northern Lights: Film and Media Studies Yearbook 10: 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Elizabeth. 2014. ‘We’re All a Bunch of Nutters!’: The Production Dynamics of Alternate Reality Games. International Journal of Communication 8: 2323–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gandini, Alessandro. 2019. Labour Process Theory and the Gig Economy. Human Relations 72: 1039–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Tosat, Clara, and Charo Sádaba-Chalezquer. 2021. Digital Intermediaries: More than New Actors on a Crowded Media Stage. Journalism and Media 2: 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, Sangita. 2019. Media Meddlers. Feminist Media Histories 5: 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesmondhalgh, David, and Sarah Baker. 2008. Creative Work and Emotional Labour in the Television Industry. Theory, Culture & Society 25: 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesmondhalgh, David, and Sarah Baker. 2013. Creative Labour: Media Work in Three Cultural Industries. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, Avery E., Seth C. Lewis, and Mark Coddington. 2016. Interacting with Audiences: Journalistic Role Conceptions, Reciprocity, and Perceptions about Participation. Journalism Studies 17: 849–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroezen, Jochem, Davide Ravasi, Innan Sasaki, Monika Żebrowska, and Roy Suddaby. 2021. Configurations of Craft: Alternative Models for Organizing Work. Academy of Management Annals 15: 502–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Anoop, and M. Shuaib Mohamed Haneef. 2018. Is Mojo (En)De-Skilling? Unfolding the Practices of Mobile Journalism in an Indian Newsroom. Journalism Practice 12: 1292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küng, Lucy. 2017. Strategic Management in the Media, 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Seth C., and Oscar Westlund. 2015. Actors, Actants, Audiences, and Activities in Cross-Media News Work. Digital Journalism 3: 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lischka, Juliane A. 2021. Logics in Social Media News Making: How Social Media Editors Marry the Facebook Logic with Journalistic Standards. Journalism 22: 430–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Chang-de. 2006. De-Skilling Effects on Journalists: ICTs and the Labour Process of Taiwanese Newspaper Reporters. Canadian Journal of Communication 31: 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, Gregory Ferrell. 2016. Introduction: What’s So Special About Media Management? In Managing Media Firms and Industries. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmelin, Nando, and Lotta Nivari-Lindström. 2017. Rethinking Creativity in Journalism: Implicit Theories of Creativity in the Finnish Magazine Industry. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 18: 334–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmelin, Nando, and Mikko Villi. 2016. Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work. Journalism Practice 10: 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Malmelin, Nando, and Mikko Villi. 2017a. Co-Creation of What? Modes of Audience Community Collaboration in Media Work. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 23: 182–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmelin, Nando, and Mikko Villi. 2017b. Media Work in Change: Understanding the Role of Media Professionals in Times of Digital Transformation and Convergence. Sociology Compass 11: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmelin, Nando, and Sari Virta. 2016. Managing creativity in change: Motivations and Constraints of Creative Work in a Media Organisation. Journalism Practice 10: 1041–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmelin, Nando, and Sari Virta. 2019. Seizing the Serendipitous Moments: Coincidental Creative Processes in Media Work. Journalism 20: 1513–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markova, Eugenia, and Sonia McKay. 2013. Migrant workers in Europe’s media. Journalism Practice 7: 282–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Chase Bowen, and Mark Deuze. 2009. The Independent Production of Culture: A Digital Games Case Study. Games and Culture 4: 276–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosavljević, Marko, and Igor Vobič. 2019. Human Still in the Loop: Editors Reconsider the Ideals of Professional Journalism Through Automation. Digital Journalism 7: 1098–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberatl, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Alttman, and Parisma Group. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 151: 264–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneux, Logan, Seth C. Lewis, and Avery E. Holton. 2019. Media Work, Identity, and the Motivations That Shape Branding Practices among Journalists: An Explanatory Framework. New Media & Society 21: 836–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murschetz, Paul Clemens, Afshin Omidi, John J. Oliver, Mahyar Kamali Saraji, and Sameera Javed. 2020. Dynamic Capabilities in Media Management Research. A Literature Review. Journal of Strategy and Management 13: 278–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Anne. 2014. ‘Men Own Television’: Why Women Leave Media Work. Media, Culture & Society 36: 1207–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi, Afshin, and Cinzia Dal Zotto. 2022. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 14: 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi, Afshin, Cinzia Dal Zotto, Esmaeil Norouzi, and José María Valero-Pastor. 2020. Media Innovation Strategies for Sustaining Competitive Advantage: Evidence from Music Download Stores in Iran. Sustainability 12: 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotidis, Kosmas, and Andreas Veglis. 2020. Transitions in Journalism—Toward a Semantic-Oriented Technological Framework. Journalism and Media 1: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Justin, Weng Marc Lim, Aron O’Cass, Andy Wei Hao, and Stefano Bresciani. 2021. Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies 45: O1–O16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, Caitlin. 2018. Engineering Consent: How the Design and Marketing of Newsroom Analytics Tools Rationalize Journalists’ Labor. Digital Journalism 6: 509–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, Robert G. 2005. Unique Characteristics and Business Dynamics of Media Products. Journal of Media Business Studies 2: 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, Robert G. 2021. Media Business Ethics, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Governance. In Handbook of Global Media Ethics. Edited by Stephen J. A. Ward. Cham: Springer, pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshandel Arbatani, Taher, Hooman Asadi, and Afshin Omidi. 2018. Media Innovations in Digital Music Distribution: The Case of Beeptunes.Com. In Competitiveness in Emerging Markets. Edited by Datis Khajeheian, Mike Friedrichsen and Wilfried Modinger. Cham: Springer, pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruotsalainen, Juho, and Mikko Villi. 2018. Hybrid Engagement: Discourses and Scenarios of Entrepreneurial Journalism. Media and Communication 6: 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, Errol. 2020. Digitizing Freelance Media Labor: A Class of Workers Negotiates Entrepreneurialism and Activism. New Media & Society 22: 105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz Weiss, Amy, and Vanessa de Macedo Higgins Joyce. 2009. Compressed Dimensions in Digital Media Occupations. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 10: 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, Merryn, and Penny O’Donnell. 2018. Once a Journalist, Always a Journalist? Industry Restructure, Job Loss and Professional Identity. Journalism Studies 19: 1021–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siapera, Eugenia. 2019. Affective Labour and Media Work. In Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions. Edited by Mark Deuze and Mirjam Prenger. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 275–86. [Google Scholar]

- Stiernstedt, Fredrik, and Irina Golovko. 2019. Volunteering as Media Work: The Case of the Eurovision Song Contest. Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research 11: 231–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiernstedt, Fredrik. 2017. Labor Market Policy and Media Work in Sweden. Medijska Istraživanja: Znanstveno-Stručni Časopis Za Novinarstvo i Medije 23: 133–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, David, David Denyer, and Palminder Smart. 2003. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. British Journal of Management 14: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villi, Mikko, and Janne Matikainen. 2015. Mobile UDC: Online Media Content Distribution among Finnish Mobile Internet Users. Mobile Media & Communication 3: 214–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villi, Mikko, and Robert G. Picard. 2019. Transformation and Innovation of Media Business Models. In Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions. Edited by Mark Deuze and Mirjam Prenger. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 121–32. [Google Scholar]

- Villi, Mikko, Mikko Grönlund, Carl-Gustav Linden, Katja Lehtisaari, Bozena Mierzejewska, Robert G. Picard, and Axel Roepnack. 2020. ‘They’re a Little Bit Squeezed in the Middle’: Strategic Challenges for Innovation in US Metropolitan Newspaper Organisations. Journal of Media Business Studies 17: 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Rimscha, M. Bjørn. 2015. The Impact of Working Conditions and Personality Traits on the Job Satisfaction of Media Professionals. Media Industries Journal 2: 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, Richard, Christa Van Raalte, and Stefania Allegrini. 2020. The ‘Shelf-Life’of a Media Career: A Study of the Long-Term Career Narratives of Media Graduates. Creative Industries Journal 13: 178–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Haiyan. 2016. ‘Naked Swimmers’: Chinese Women Journalists’ Experience of Media Commercialization. Media, Culture & Society 38: 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlund, Oscar, and Seth C. Lewis. 2014. Agents of Media Innovations: Actors, Actants, and Audiences. The Journal of Media Innovations 1: 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witschge, Tamara, and Gunnar Nygren. 2009. Journalistic Work: A Profession Under Pressure? Journal of Media Business Studies 6: 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. Denis, and Cheryl Ann Lambert. 2016. Impediments to Journalistic Ethics: How Taiwan’s Media Market Obstructs News Professional Practice. Journal of Media Ethics 31: 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).