Saving Lives and Changing Minds with Twitter in Disasters and Pandemics: A Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

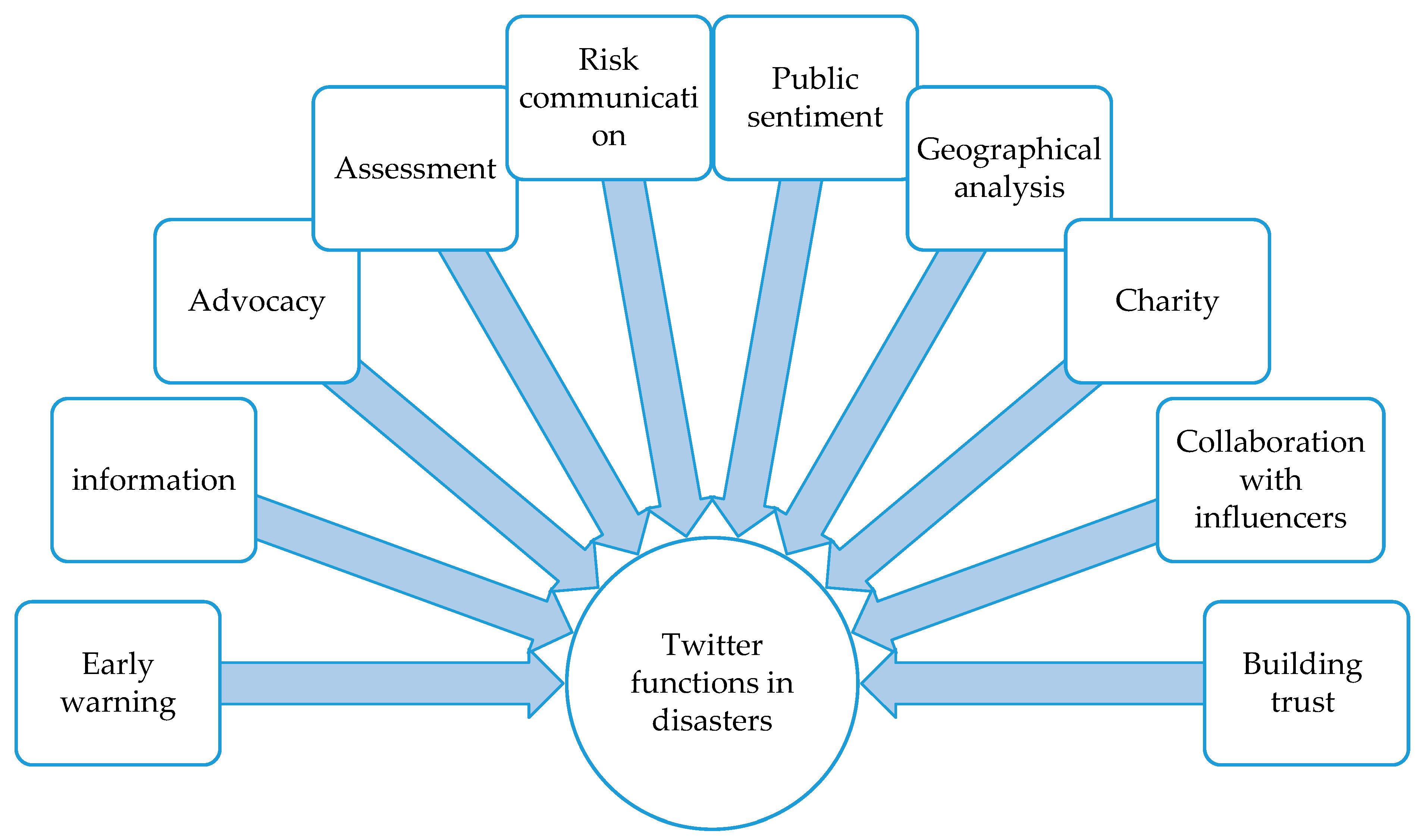

- What are Twitter’s functions in a disaster?

- How can governments and emergency organizations use Twitter to manage disasters more effectively?

- How was Twitter used at different stages of disaster management including mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Processes

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Search Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Early Warning

3.2. Disseminating Information

3.3. Advocacy

3.4. Personal Gains

3.5. Assessment

3.6. Risk Communication

3.7. Tracking Public Mood

3.8. Geographical Analysis

3.9. Charity

3.10. Collaboration with Influencers

3.11. Building Trust

3.12. Other Issues

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications for Practice

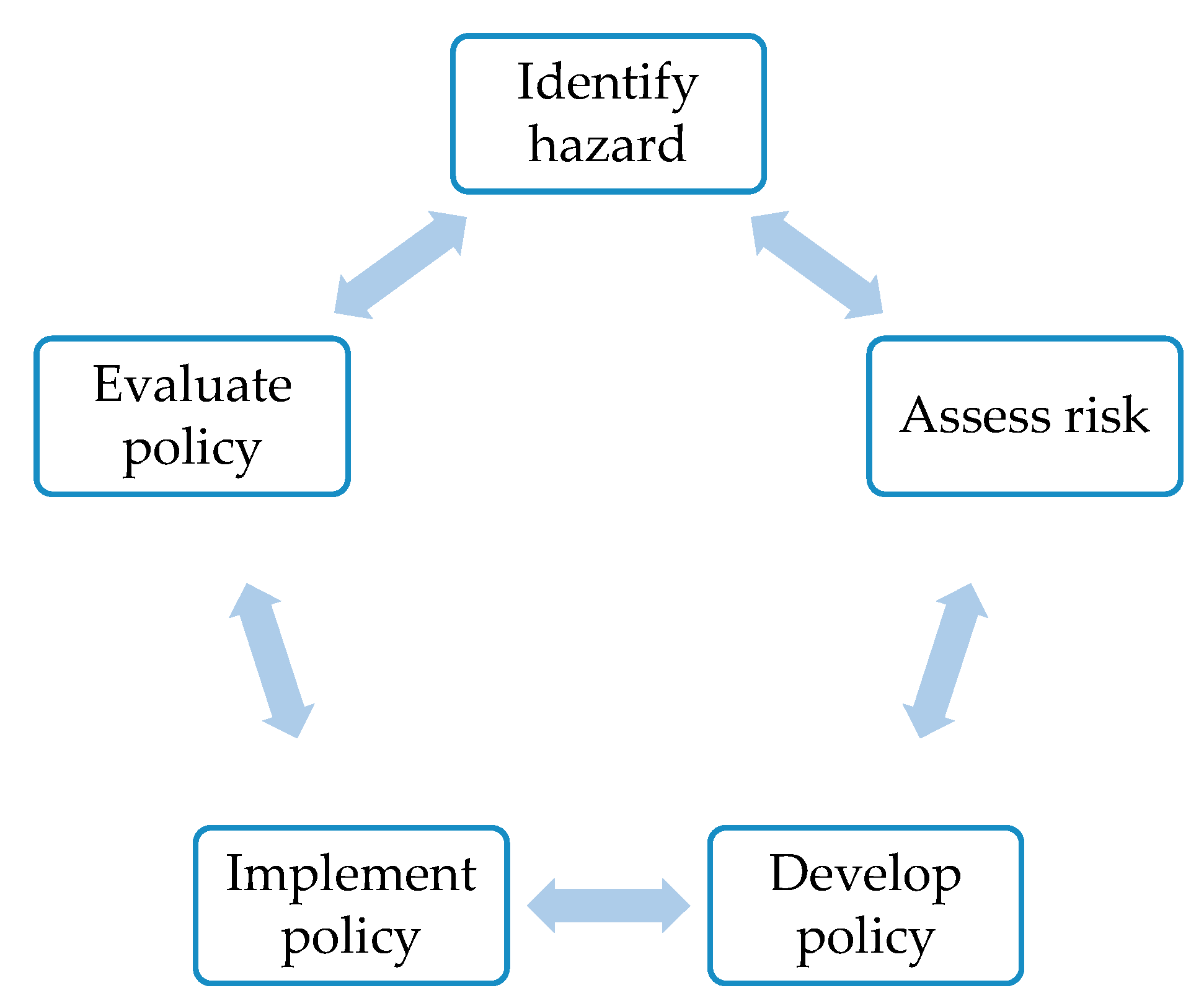

5.2. Implications for Policy

5.3. Implications for Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abedin, Babak, Abdul Babar, and Alireza Abbasi. 2014. Characterization of the Use of Social Media in Natural Disasters: A Systematic Review. Paper presented at 2014 IEEE Fourth International Conference on Big Data and Cloud Computing, Sydney, Australia, December 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Acar, Adam, and Yuya Muraki. 2011. Twitter for crisis communication: Lessons learned from Japan’s tsunami disaster. International Journal of Web Based Communities 7: 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Wasim, Peter A. Bath, Laura Sbaffi, and Gianluca Demartini. 2018. Moral Panic through the Lens of Twitter: An Analysis of Infectious Disease Outbreaks. Paper presented at 9th International Conference on Social Media and Society, Copenhagen, Denmark, July 18–20; pp. 217–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ahweyevu, Jennifer O., Ngozi P. Chukwudebe, Brittany M. Buchanan, Jingjing Yin, Bishwa B. Adhikari, Xiaolu Zhou, Zion Tsz Ho Tse, Gerardo Chowell, Martin I. Meltzer, and Isaac Chun-Hai Fung. 2020. Using Twitter to Track Unplanned School Closures: Georgia Public Schools, 2015-17. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhayyat, Abdulaziz, and Kishan Pankhania. 2020. Defining COVID-19 as a Disaster Helps Guide Public Mental Health Policy. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avasthi, Ranjan. 2017. 55.1 Social Media and Disasters: A Literature Review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 56: S81. [Google Scholar]

- Budhwani, Henna, and Ruoyan Sun. 2020. Referencing the novel coronavirus as the” Chinese virus” or” China virus” on Twitter: COVID-19 stigma. Journal of Medical Internet Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, Kathleen M., Momin Malik, Peter M. Landwehr, Jürgen Pfeffer, and Michael Kowalchuck. 2016. Crowd sourcing disaster management: The complex nature of Twitter usage in Padang Indonesia. Safety Science 90: 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, Meg. 2014. How Twitter may have helped Nigeria contain Ebola. BMJ 349: g6946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charles-Smith, Lauren E., Tera L. Reynolds, Mark A. Cameron, Mike Conway, Eric H. Y. Lau, Jennifer M. Olsen, Julie A. Pavlin, Mika Shigematsu, Laura C. Streichert, and Katie J. Suda. 2015. Using social media for actionable disease surveillance and outbreak management: A systematic literature review. PLoS ONE 10: e0139701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatfield, Akemi Takeoka, and Christopher G Reddick. 2017. All hands on deck to tweet# sandy: Networked governance of citizen coproduction in turbulent times. Government Information Quarterly 35: 259–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Seong Eun, Kyujin Jung, and Han Woo Park. 2013. Social media use during Japan’s 2011 earthquake: How Twitter transforms the locus of crisis communication. Media International Australia 149: 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Guy Paul, Jr., Violet Yeager, Frederick M Burkle Jr., and Italo Subbarao. 2015. Twitter as a potential disaster risk reduction tool. Part III: Evaluating variables that promoted regional Twitter use for at-risk populations during the 2013 Hattiesburg F4 tornado. PLoS Currents 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiner, Michael S., Cherie Fathy, Jessica Kim, Katherine Niemeyer, David Ramirez, Sarah F. Ackley, Fengchen Liu, Thomas M. Lietman, and Travis C. Porco. 2017. Facebook and Twitter vaccine sentiment in response to measles outbreaks. Health Informatics Journal 25: 1116–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doan, Son, Bao-Khanh Ho Vo, and Nigel Collier. 2011. An analysis of Twitter messages in the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake. Paper presented at the International Conference on Electronic Healthcare, Málaga, Spain, November 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, Emilio. 2020. # COVID-19 on Twitter: Bots, Conspiracies, and Social Media Activism. arXiv arXiv:2004.09531. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, King-Wa, Hai Liang, Nitin Saroha, Zion Tsz Ho Tse, Patrick Ip, and Isaac Chun-Hai Fung. 2016. How people react to Zika virus outbreaks on Twitter? A computational content analysis. American Journal of Infection Control 44: 1700–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharavi, Erfaneh, Neda Nazemi, and Faraz Dadgostari. 2020. Early Outbreak Detection for Proactive Crisis Management Using Twitter Data: COVID-19 a Case Study in the US. arXiv arXiv:2005.00475. [Google Scholar]

- Golder, Su, Ari Klein, Arjun Magge, Karen O’Connor, Haitao Cai, and Davy Weissenbacher. 2020. Extending a Chronological and Geographical Analysis of Personal Reports of COVID-19 on Twitter to England, UK. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Briony, Mark Weal, and David Martin. 2016. Social media and disasters: A new conceptual framework. Paper presented at ISCRAM 2016 Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, May 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Guha-Sapir, Debby, Femke Vos, Regina Below, and Sylvain Ponserre. 2016. Annual Disaster Statistical Review 2016: The Numbers and Trends. Brussels: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED). [Google Scholar]

- Gurman, Tilly A., and Nicole Ellenberger. 2015. Reaching the global community during disasters: Findings from a content analysis of the organizational use of Twitter after the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Journal of Health Communication 20: 687–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, Tonya Cross, Leia Y. Saltzman, and Patrick S. Bordnick. 2020. Behavioral Health and Response for COVID-19. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, Mohammad, Seyedeh Samaneh Miresmaeeli, and Neda Eskandary. 2018. Celebrity Role in Sarpol-e Zahab Earthquake in Iran 2017. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 13: 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Houston, J. Brian, Joshua Hawthorne, Mildred F. Perreault, Eun Hae Park, Marlo Goldstein Hode, Michael R. Halliwell, Sarah E. Turner McGowen, Rachel Davis, Shivani Vaid, and Jonathan A. McElderry. 2015. Social media and disasters: A functional framework for social media use in disaster planning, response, and research. Disasters 39: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbin, Kia, and Vahid Rahmanian. 2020. Using twitter and web news mining to predict COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanhabua, Nattiya, and Wolfgang Nejdl. 2013. Understanding the diversity of tweets in the time of outbreaks. Paper presented at 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, May 13–17; pp. 1335–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kankanamge, Nayomi, Tan Yigitcanlar, Ashantha Goonetilleke, and Md Kamruzzaman. 2020. Determining disaster severity through social media analysis: Testing the methodology with South East Queensland Flood tweets. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 42: 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmegam, Dhivya, and Bagavandas Mappillairaju. 2020. Spatio-temporal distribution of negative emotions on Twitter during floods in Chennai, India, in 2015: A post hoc analysis. International Journal of Health Geographics 19: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Simon. 2020. Digital in 2020: Global digital overview. In We Are Social, Hootsuite. New York: Kepios. [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa, Katsushige, and Scott A. Hale. 2020. Social Media and Early Warning Systems for Natural Disasters: A Case Study of Typhoon Etau in Japan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostkova, Patty, Martin Szomszor, and Connie St Louis. 2014. #swineflu: The Use of Twitter as an Early Warning and Risk Communication Tool in the 2009 Swine Flu Pandemic. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems 5: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzy, Ramez, Joseph Abi Jaoude, Afif Kraitem, Molly B. El Alam, Basil Karam, Elio Adib, Jabra Zarka, Cindy Traboulsi, Elie W. Akl, and Khalil Baddour. 2020. Coronavirus Goes Viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 Misinformation Epidemic on Twitter. Cureus 12: e7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kryvasheyeu, Yury, Haohui Chen, Nick Obradovich, Esteban Moro, Pascal Van Hentenryck, James Fowler, and Manuel Cebrian. 2016. Rapid assessment of disaster damage using social media activity. Science Advances 2: e1500779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwon, Jiye, Connor Grady, Josemari T. Feliciano, and Samah J. Fodeh. 2020. Defining Facets of Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Twitter Analysis. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Hai, Isaac Chun-Hai Fung, Zion Tsz Ho Tse, Jingjing Yin, Chung-Hong Chan, Laura E. Pechta, Belinda J. Smith, Rossmary D. Marquez-Lameda, Martin I. Meltzer, Keri M. Lubell, and et al. 2019. How did Ebola information spread on twitter: Broadcasting or viral spreading? BMC Public Health 19: 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Rojas, María, María del Carmen Pardo-Ferreira, and Juan Carlos Rubio-Romero. 2018. Twitter as a tool for the management and analysis of emergency situations: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Information Management 43: 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medford, Richard J., Sameh N. Saleh, Andrew Sumarsono, Trish M. Perl, and Christoph U. Lehmann. 2020. An “Infodemic”: Leveraging High-Volume Twitter Data to Understand Public Sentiment for the COVID-19 Outbreak. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendoza, Marcelo, Barbara Poblete, and Carlos Castillo. 2010. Twitter under Crisis: Can we trust what we RT? Paper presented at First Workshop on Social Media Analytics, Washington, DC, USA, July 25. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, Kate, Joanne Chang, Abi Beatson, and Chris Morahan. 2015. Public perceptions of building seismic safety following the Canterbury earthquakes: A qualitative analysis using Twitter and focus groups. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 13: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkamala, Alivelu, and Roman Beck. 2016. Enhancing Disaster Management through Social Media Analytics to Develop Situation Awareness What Can Be Learned from Twitter Messages about Hurricane Sandy? Paper presented at PACIS 2016, Chiayi, Taiwan, June 27. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, Dhiraj. 2018. Twitter. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nsoesie, Elaine O., John S Brownstein, Naren Ramakrishnan, and Madhav V. Marathe. 2014. A systematic review of studies on forecasting the dynamics of influenza outbreaks. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 8: 309–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD. 2016. Trends in Risk Communication Policies and Practices. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Martínez, Yeimer, and Luisa F. Jiménez-Arcia. 2017. Yellow fever outbreaks and Twitter: Rumors and misinformation. American Journal of Infection Control 45: 816–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oyeyemi, Sunday Oluwafemi, Elia Gabarron, and Rolf Wynn. 2014. Ebola, Twitter, and misinformation: A dangerous combination? BMJ 349: g6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palenchar, Michael J. 2010. Risk communication. In The Sage Handbook of Public Relations. London: SAGE Publishing, pp. 447–61. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Michael J., Mark Dredze, and David Broniatowski. 2014. Twitter improves influenza forecasting. PLoS Currents 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, Jennie, Helen Roberts, Amanda Sowden, Mark Petticrew, Lisa Arai, Mark Rodgers, Nicky Britten, Katrina Roen, and Steven Duffy. 2006. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version 1. Lancashire: Lancaster University, p. b92. [Google Scholar]

- Pourebrahim, Nastaran, Selima Sultana, John Edwards, Amanda Gochanour, and Somya Mohanty. 2019. Understanding communication dynamics on Twitter during natural disasters: A case study of Hurricane Sandy. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 37: 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regina, E. Lundgren, and H. McMakin Andrea. 2018. Approaches to Communicating Risk. In Risk Communication: A Handbook for Communicating Environmental, Safety, and Health Risks. Piscataway: IEEE, pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Hans, Shahbaz Syed, and Salim Rezaie. 2020. The twitter pandemic: The critical role of twitter in the dissemination of medical information and misinformation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. CJEM, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rufai, Sohaib R, and Catey Bunce. 2020. World leaders’ usage of Twitter in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A content analysis. Journal of Public Health. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmani, Ibrahim, Hamed Seddighi, and Maryam Nikfard. 2020. Access to Health Care Services for Afghan Refugees in Iran in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, Abeed, Sahithi Lakamana, Whitney Hogg-Bremer, Angel Xie, Mohammed Ali Al-Garadi, and Yuan-Chi Yang. 2020. Self-reported COVID-19 symptoms on Twitter: An analysis and a research resource. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 27: 1310–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seddighi, Hamed. 2020. COVID-19 as a Natural Disaster: Focusing on Exposure and Vulnerability for Response. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddighi, Hamed, Maureen F. Dollard, and Ibrahim Salmani. 2020. Psychosocial Safety Climate of Employees during COVID-19 in Iran: A Policy Analysis. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, Karishma, Sungyong Seo, Chuizheng Meng, Sirisha Rambhatla, Aastha Dua, and Yan Liu. 2020. Coronavirus on Social Media: Analyzing Misinformation in Twitter Conversations. arXiv arXiv:2003.12309. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Lisa, Shweta Bansal, Leticia Bode, Ceren Budak, Guangqing Chi, Kornraphop Kawintiranon, Colton Padden, Rebecca Vanarsdall, Emily Vraga, and Yanchen Wang. 2020. A first look at COVID-19 information and misinformation sharing on Twitter. arXiv arXiv:2003.13907. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Brian G. 2010. Socially distributing public relations: Twitter, Haiti, and interactivity in social media. Public Relations Review 36: 329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, Nirupama Dharmavaram, Chei Sian Lee, and Dion Hoe-Lian Goh. 2011. Tweet me home: Exploring information use on Twitter in crisis situations. Paper presented at International Conference on Online Communities and Social Computing, Las Vegas, NV, USA, July 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- St Louis, Connie, and Gozde Zorlu. 2012. Can Twitter predict disease outbreaks? BMJ 344: e2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba, Rajib, and Tung Bui. 2017. Online convergence behavior, social media communications and crisis response: An empirical study of the 2015 Nepal earthquake police twitter project. Paper presented at 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, January 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Bruno, Edson C Tandoc Jr., and Christine Carmichael. 2015. Communicating on Twitter during a disaster: An analysis of tweets during Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. Computers in Human Behavior 50: 392–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Sho, Kazunori Manaka, Takafumi Hori, Tetsuaki Arai, and Hirokazu Tachikawa. 2020. An Experience of the Ibaraki Disaster Psychiatric Assistance Team on the Diamond Princess Cruise Ship: Mental Health Issues Induced by COVID-19. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Lu, Bijie Bie, Sung-Eun Park, and Degui Zhi. 2018. Social media and outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases: A systematic review of literature. American Journal of Infection Control 46: 962–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, Robert, Naoya Ito, Hinako Suda, Fangyu Lin, Yafei Liu, Ryo Hayasaka, Ryuzo Isochi, and Zian Wang. 2012. Trusting tweets: The Fukushima disaster and information source credibility on Twitter. Paper presented at 9th International ISCRAM Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, April 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zheye, Xinyue Ye, and Ming-Hsiang Tsou. 2016. Spatial, temporal, and content analysis of Twitter for wildfire hazards. Natural Hazards 83: 523–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, Katrin, Axel Bruns, Jean Burgess, Merja Mahrt, and Cornelius Puschmann. 2014. Twitter and Society. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Wicke, Philipp, and Marianna M. Bolognesi. 2020. Framing COVID-19: How we conceptualize and discuss the pandemic on Twitter. arXiv arXiv:2004.06986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Roger, and Jenine K. Harris. 2017. Geospatial Distribution of Local Health Department Tweets and Online Searches about Ebola during the 2014 Ebola Outbreak. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 12: 287–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, Hyekyung, Hyeon Sung Cho, Eunyoung Shim, Jong Koo Lee, Kihwang Lee, Gilyoung Song, and Youngtae Cho. 2017. Identification of Keywords From Twitter and Web Blog Posts to Detect Influenza Epidemics in Korea. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 12: 352–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Kai-Cheng, Christopher Torres-Lugo, and Filippo Menczer. 2020. Prevalence of Low-Credibility Information on Twitter during the COVID-19 Outbreak. arXiv arXiv:2004.14484. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Yang, Cheng Zhang, Chao Fan, Wenlin Yao, Ruihong Huang, and Ali Mostafavi. 2019. Exploring the emergence of influential users on social media during natural disasters. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 38: 101204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Disaster | Finding | Disaster Phase | Country | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Typhoon | People and organizations have used Twitter more often to retweet second-hand information/social networking users in Philippines are more likely to pay attention to news released in traditional media than social media. | response | Philippines | (Takahashi et al. 2015) |

| 2 | Earthquake, Tsunami | The results suggest that Twitter can be used to track and measure the public’s mood after disasters. | Response, Recovery | Japan | (Doan et al. 2011) |

| 3 | Wildfire | The geographic awareness of people is strong about critical events and people are interested in tweeting about fire damage, firefighting and thanking firefighters/official tweets play a key role in the firefighting network. | Preparedness, Response | USA | (Wang et al. 2016) |

| 4 | Earthquake | Rumors about earthquakes spread more than anything else on Twitter. | Response | Chile | (Mendoza et al. 2010) |

| 5 | Earthquake | Twitter was used as a tool to report on the situation by the affected people. This article suggests that Twitter can be used as a tool for rapid assessment of an accident, as well as for the publication of accurate information by officials. | Response | Japan | (Acar and Muraki 2011) |

| 6 | Earthquake | Twitter is useful as a tool to show people’s mental health, especially in the early days of a disaster. | Response | Japan | (Cho et al. 2013) |

| 7 | Earthquake | During an earthquake, organizations used Twitter as a tool for risk communication, to collect public donations and to provide psychological support. | Response, Recovery | Haiti | (Gurman and Ellenberger 2015) |

| 8 | Earthquake | Twitter was used for disaster assessment, response monitoring and to help the affected people. | Response | Haiti | (Smith 2010) |

| 9 | Storm | A lot of first-hand information was published about the current situation. Twitter is useful for disaster assessment. | Response | USA | (Mukkamala and Beck 2016) |

| 10 | Tornado | People trusted personal accounts more than governmental accounts to find out about a tornado. Influential people play a big role in providing the right information. Using the right hashtag will help to spread information on Twitter. | Response | USA | (Cooper et al. 2015) |

| 11 | Earthquake | Twitter acted as an effective and efficient tool for communication between people and aid organizations in an earthquake. | Response | Nepal | (Subba and Bui 2017) |

| 12 | Storm | Establishing a strategy for using Twitter in times of disaster is essential. Twitter is a great tool for publishing content, but it has been suggested that influential people should be used to publish it. | Preparedness, Response | USA | (Chatfield and Reddick 2017) |

| 13 | Tsunami | Twitter is a powerful tool for early warning during tsunamis, especially for Indonesia which has a high population distribution. | Preparedness | Indonesia | (Carley et al. 2016) |

| 14 | Volcanic eruption | At the time of the eruption, a lot of misinformation was spread. Therefore, it is necessary for government agencies to have an information strategy in case of disasters so that they can publish the correct information from the first moment. | Response | Iceland | (Sreenivasan et al. 2011) |

| 15 | Earthquake, Tsunami | A third of the tweets were released from low credibility sources. Tweets published by anonymous and unidentified accounts have lowered credibility. | Response | Japan | (Thomson et al. 2012) |

| 16 | Flood | Tweet analysis helped to identify the effects of flooding on people’s mental health. This can affect the design of psychosocial support programs. | Response, Recovery | India | (Karmegam and Mappillairaju 2020) |

| 17 | Ebola Outbreak | To spread information about Ebola, influential people on Twitter shared information. It is recommended that these people be helped to publish correct information. | Preparedness | Global | (Liang et al. 2019) |

| 18 | COVID-19 pandemic | Publishing false information about pandemics has reached alarming levels that endanger public health. | Preparedness | Global | (Kouzy et al. 2020) |

| 19 | COVID-19 pandemic | There was a geographic relationship between the flow of information about the pandemic and the identification of new cases of COVID-19. | Preparedness, Response | Global | (Singh et al. 2020) |

| 20 | COVID-19 pandemic | Using Twitter text and image analysis, the prevalence in each geographical area can be predicted. | Preparedness | Global | (Jahanbin and Rahmanian 2020) |

| 21 | COVID-19 pandemic | Twitter bots are used to promote misinformation and political information about COVID-19. | Preparedness | USA | (Ferrara 2020) |

| 22 | COVID-19 pandemic | At the same time, Twitter played a useful role in promoting positive information and a negative role in disseminating misinformation about the COVID-19. | Preparedness | Global | (Rosenberg et al. 2020) |

| 23 | COVID-19 pandemic | The community’s sentiment can be assessed using tweet analysis. | Response | USA | (Medford et al. 2020) |

| 24 | COVID-19 pandemic | Policies adopted in the United States and their effects on society were analyzed using Twitter. | Response | USA | (Sharma et al. 2020) |

| 25 | COVID-19 pandemic | Analyzing the tweets of the leaders of the G7 on the coronavirus showed that Twitter has become a powerful tool for world leaders to disseminate information about public health during the pandemic. | Preparedness | G7 countries | (Rufai and Bunce 2020) |

| 26 | COVID-19 pandemic | Tweet analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States showed that this pandemic has a political effect on society. Twitter bots played a major role in disseminating invalid information. | Preparedness | USA | (Yang et al. 2020) |

| 27 | COVID-19 pandemic | The dominant discourse in society on the COVID-19 pandemic can be identified and analyzed on Twitter. | Response | Global | (Wicke and Bolognesi 2020) |

| 28 | COVID-19 pandemic | Wrong information was widely published on Twitter. | preparedness | Global | (Sharma et al. 2020) |

| 29 | COVID-19 pandemic | Analyzing Twitter data on the specifications of people with coronavirus, it was suggested that in addition to using clinical data about people with the virus, Twitter data should also be used. | Response | Global | (Sarker et al. 2020) |

| 30 | COVID-19 pandemic | Using tweet analysis in the United States, various aspects of social distancing (methods of preventing infection) were identified and analyzed. | Preparedness | USA | (Kwon et al. 2020) |

| 31 | COVID-19 pandemic | The study found that tweet analysis could be crucial in the geographical distribution and density of the virus outbreak in the UK. | Response | UK | (Golder et al. 2020) |

| 32 | COVID-19 pandemic | The study found that tweet analysis could help to identify geographic distribution and the prevalence of the virus in the United States. | Response | USA | (Gharavi et al. 2020) |

| 33 | COVID-19 pandemic | Tweet analysis showed that a large number of tweets have stigmatized China because the first cases of this pandemic were observed in China. | Response | USA | (Budhwani and Sun 2020) |

| 34 | Outbreaks | Twitter is useful in predicting disease outbreaks. | Mitigation | Global | (St Louis and Zorlu 2012) |

| 35 | Zika outbreak | Tweets showed the social impacts of the epidemic, the role of organizations and policies, information on the transmission of the disease and the lessons learned. | Preparedness, Response | Global | (Fu et al. 2016) |

| 36 | Flu outbreak | The use of Twitter data is more accurate in modeling flu epidemic prediction than Google data. | Response | USA | (Paul et al. 2014) |

| 37 | Yellow Fever outbreak | The amount of misinformation about yellow fever was much larger than that of correct information, and misinformation was shared and retweeted, which can be dangerous to public health. | Preparedness | Global | (Ortiz-Martínez and Jiménez-Arcia 2017) |

| 38 | Outbreaks | Twitter can act as an early warning system during epidemics. Twitter can also help to detect the prevalence of geography at different times and places and can be analyzed from time to time. | Preparedness | Global | (Kanhabua and Nejdl 2013) |

| 39 | Flu and Ebola Outbreaks | Analyzing tweets about the 2009 and 2014 Ebola epidemics revealed that Twitter could help to analyze the state of mental health and general fear during the epidemic. | Response | Global | (Ahmed et al. 2018) |

| 40 | Ebola outbreak | During the 2014 Ebola outbreak in East Africa, a lot of misinformation was spread on Twitter. Proper information needs to be disseminated through influential people during epidemics. | Preparedness | East Africa | (Oyeyemi et al. 2014) |

| 41 | Flu outbreak | Twitter was used as a tool for early warning during the 2009 flu and risk communications in the United States. | Preparedness | USA | (Kostkova et al. 2014) |

| 42 | Ebola outbreak | Twitter helped to spread information about Ebola in Nigeria. | Preparedness | Nigeria | (Carter 2014) |

| 43 | Outbreaks | The potential value of incorporating Twitter into existing unplanned school closure (USC) monitoring systems was examined. | Response | USA | (Ahweyevu et al. 2020) |

| 44 | Influenza Epidemics | Extending the capacity of surveillance systems for detecting emerging influenza was examined. | Response | Korea | (Woo et al. 2017) |

| 45 | Ebola | Social media can be used to communicate possible disease outbreaks in a timely manner, and using online search data to tailor messages to align with the public health interests of their constituents was considered by government officials. | Preparedness | USA | (Wong and Harris 2017) |

| Stakeholders | Type of Hazards | Twitter Functions | Tweets Characteristics | Disaster Risk Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governments, Emergency organizations, Celebrities, People, News agencies, Donors, Affected people | Disasters triggered by natural and technological hazards, pandemics and complex disasters | Early warning, disseminating information, advocacy, assessment, risk communication, public sentiment, geographical analysis, charity, collaboration with influencers and building trust | Transparency, on-time messages, using different local languages, Using different media (text, video, photo) | Using Twitter during different phases including mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seddighi, H.; Salmani, I.; Seddighi, S. Saving Lives and Changing Minds with Twitter in Disasters and Pandemics: A Literature Review. Journal. Media 2020, 1, 59-77. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia1010005

Seddighi H, Salmani I, Seddighi S. Saving Lives and Changing Minds with Twitter in Disasters and Pandemics: A Literature Review. Journalism and Media. 2020; 1(1):59-77. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia1010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeddighi, Hamed, Ibrahim Salmani, and Saeideh Seddighi. 2020. "Saving Lives and Changing Minds with Twitter in Disasters and Pandemics: A Literature Review" Journalism and Media 1, no. 1: 59-77. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia1010005

APA StyleSeddighi, H., Salmani, I., & Seddighi, S. (2020). Saving Lives and Changing Minds with Twitter in Disasters and Pandemics: A Literature Review. Journalism and Media, 1(1), 59-77. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia1010005