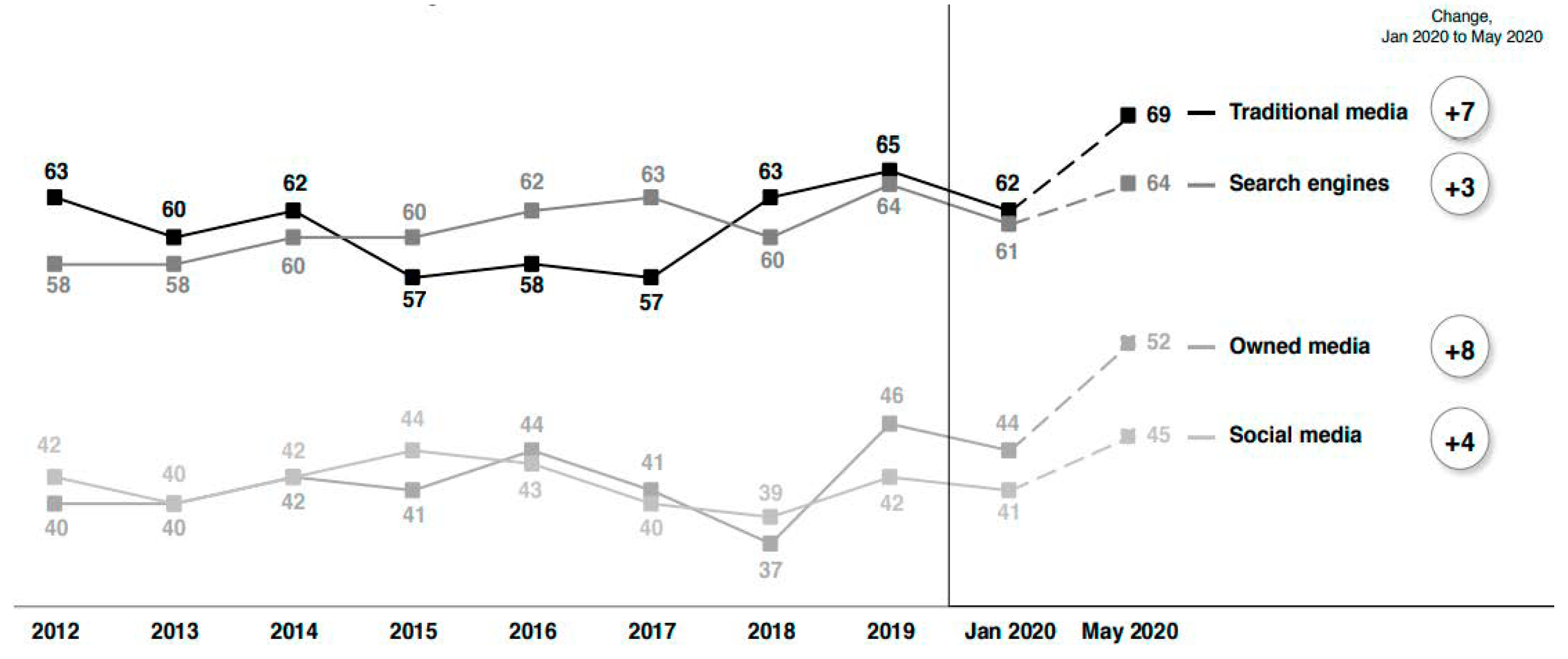

1. Introduction

It is well known how informative media is a fundamental lens through which people see society and the world. Thanks to their reach and omnipresence, the individuals have now more opportunities to find news and information than ever before. In addition to traditional media, such as television, newspapers and radio, the circulation of news on the Internet and social networks offers people the possibility of being exposed to information, even if they do not purposely seek it out. Due to the growing supply, several studies have been listing factors that determine which media people consult, and the effects of privileged exposure to each of these media.

At first glance, the abundance of information can be considered a favorable factor for obtaining better-informed citizens, especially since the volume and diversity of information in the media environment promote learning about the most relevant public issues (

Barabas and Jerit 2009). In times of crisis, as are those in which large-scale natural disasters, terrorist attacks or disease outbreaks occur, the importance of this factor increases and information from the media becomes a key element for the functioning of society. Due to the high level of uncertainty, it is in the media that most people usually trust to understand the environment in which they live and make decisions regarding that environment. Similarly, in these situations, the media’s influence is often amplified. Especially in crisis management situations, the use of reliable sources of information is one of the most important factors of social behavior (

Longstaff 2005).

This study is about how individuals informed themselves about the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal, in the days following the declaration of the state of emergency (18 March 2020). The rapid spread of the disease was accompanied by an equal surge of information through social and conventional media, allowing a vast torrent of “news” about the origins of the virus and ways to fight it to circulate as quickly as the infection. With the arrival and spread of COVID-19, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), claimed, in February 2020, “We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we are fighting an

infodemic” (

WHO 2020). In such a situation, people must have access to news and information that they trust and that can help them understanding, the various aspects related to the nature of the coronavirus (which is important to protect themselves), but also independent information on how governments and other officials respond to the pandemic (with decisive importance for the assessment of political action).

Unquestionably, both true information and the various types of wrong information (from inaccurate to purposely false information) shape the way people understand and respond to the ongoing public health crisis, as well as the assessment of how institutions are dealing with it. As has been known for a long time, it is risk perceptions (pseudo-environments, in Walter Lippman’s terms), and not the real risk, that determine how people respond to crises (

Glik 2007).

Traditionally, mass media such as television and newspapers, which carry information from authorized sources, played the role of transmitting official information. However, over the past few decades, the rise of the Internet, and in particular of social media, has substantially changed the media environment. Firstly, because these media challenge the role of the mass media, by providing effective channels to reach alternative sources of information (

Castells 2007). Despite the very different nature of these two types of media (conventional media and social media), they are highly interconnected (

Napoli 2019). Their combined and permanent use sustains and, to a large extent, deepens the dependence of individuals on the media system. As a whole, the vast volume of news and information surrounding COVID-19—the ambiguity, uncertainty and misleading nature, and sometimes the low quality, or the totally false nature of some of this information—justify the use by WHO of the term

infodemic. In March of this year, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said, “At WHO, we are not only fighting the virus but also

troll and conspiracy theorists who spread wrong information and hamper the response to the outbreak” (

WHO 2020). With the

infodemic neologism, WHO wanted, in the days when the fear of the coronavirus spread, to point out another danger of societies in the age of social media: the distortion of reality in the buzz of echoes and comments both about real facts and about facts frequently invented (

Cinelli et al. 2020). A US State Department study, initially published in

The Washington Post (29 February 2020), reported that approximately 2 million tweets spread coronavirus conspiracy theories during the three weeks that the outbreak began to spread outside of China. Among the most common publications were those that described the virus as “a biological weapon”. This and other false rumors represented 7% of the total tweets studied and were characterized as “potentially impacting on the most popular social media conversations”, according to the report obtained by

The Washington Post. It should be noted that the new coronavirus is, for practical purposes, identified by researchers as a single pathogen microorganism, properly diagnosed and tested, with its dissemination mapped. Nevertheless, we find that, in addition to the proven false misinformation, deliberately elaborated and manipulated, identified by fact checkers, much of what we learned about the new coronavirus remains difficult to separate clearly and cleanly in terms of information and disinformation, true and false, reliable and unreliable (

Brennen et al. 2020). This perception leads the majority of the public to further emphasize the importance of the reliability of sources, whether they are professional media of information, public authorities or social media platforms (

Nielsen and Graves 2017;

Newman et al. 2017).

This study takes as a starting point the importance and dependence of the media (

Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur 1976) to obtain information about the pandemic. Based on a questionnaire applied to a sample of 240 individuals, in Portugal, in the first week in which the state of emergency was in force, this research analyzes how people accessed information about COVID-19 and how they assessed the reliability of different sources and communication platforms. The type of relationship with information—the search for information or accidental exposure to information—will also be considered from the perspective of the quality of the information achieved. Finally, it analyzes the association between the type of medium to which they attributed greater confidence, and the adherence to content identified as misinformation about the pandemic.

3. Hypotheses and Methodology

With the previous theoretical and conceptual framework as a reference, and using the COVID-19 pandemic information theme as a topic of analysis, this article aims to investigate the relationship between people’s dependence on the media system (encompassing conventional media) and social media, the choices they make within that system and some of the consequences that result from those options. We consider, for this purpose, the importance of variables as the primary medium of obtaining information (and in this case, if the primary medium used involves the active search or passive and accidental exposure to information) and the confidence (defined by the indication of the most reliable medium). Considering the aforementioned variables, the study aims to analyze adherence to forms of misinformation and conspiracy theories, confronting the individuals studied with some of the false news or rumors without proof or evidence that, regarding COVID-19, circulated more notoriously in the media environment.

We start from the premise that the studied individuals express feelings of dependence on the media concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. This premise will be supported from the observation of two conditions: the wide and recurring recourse to the different types of medium available (and not just those specifically informative or just those referred to as trustworthy) and the enhancement of the role of the media as a source of information about the problem.

From this premise, it is important to assess which are the most important sources for obtaining information about COVID-19. In a crisis situation, in which conventional media and social media coexist, interrelate, and are widely accessible, which media valued individuals to learn about the COVID-19 pandemic? In line with the most recent literature and research, although both types of media are widely consulted, it will be expected that traditional media will tend to be preferred as the main source of information about the COVID-19 pandemic over social media. Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Individuals prefer traditional media over social media as the main source of information about the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following the previous hypothesis, and in close association with this, we consider the attribute of trust granted to each type of media. The choice of the main source will tend to be associated with the attribute of trust and to reveal a close distribution. Along the same lines, traditional media will tend to be indicated as more reliable as a source for the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to social media.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Individuals rely more on traditional media than on social media as a source of information about the COVID-19 pandemic.

Another dimension to take into account is the quality of the information that reaches each individual, and the relationship they establish with their main source of information. We take as a reference the concept described above of NFM, which indicates that individuals who privilege specifically informative media (those who seek and choose from the infinity of news available) derive a greater benefit from accessing information. Conversely, those who do not actively seek information, but are exposed to it accidentally (namely in social media), will have lower gains in knowledge, despite the volume of information they consume. To this end, we consider that the quality of information is intrinsically related to an essential attribute: truth, as a condition of the quality of information and its first attribute. In this sense, we will analyze the existence (or not) of a dependency association between the source that individuals designated as the “principal” source of the main information about the COVID-19 pandemic and adherence to false news/rumors. The hypothesis that we will test is as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The acceptance of disinformation is associated with the source of information chosen as the main one.

From the submission of a questionnaire distributed and expanded following the snowball model, a non-probabilistic, convenience sample was obtained, composed of 244 individuals from Portugal, with a balanced distribution in terms of gender and age groups. The data were collected during the first week of the state of emergency (between 19 and 26 March 2020), and reveal information about the news/information sources on the COVID-19 pandemic, identifying which media are used, the main medium and the most reliable medium for each individual. Finally, having been suggested some of the main false theories about the COVD-19, the degree of acceptance of these same theories was questioned. The data were analyzed using elements of descriptive statistics, and tests of association of variables were carried out through contingency tables, performed with the IBM SPSS data analysis software.

4. Results

The first data we sought to obtain aimed at supporting (or refuting) the premise regarding the existence of feelings of dependence on individuals to the media system, concerning obtaining information about COVID-19. To that end, individuals were consulted about the various types of media they used as sources of information, and also about the extent to which they considered them to be valid—namely, questioning whether the information they transmit should be considered. The results support the proposed premise, by demonstrating that, clearly, the media assumed themselves as a practically exclusive mode of information.

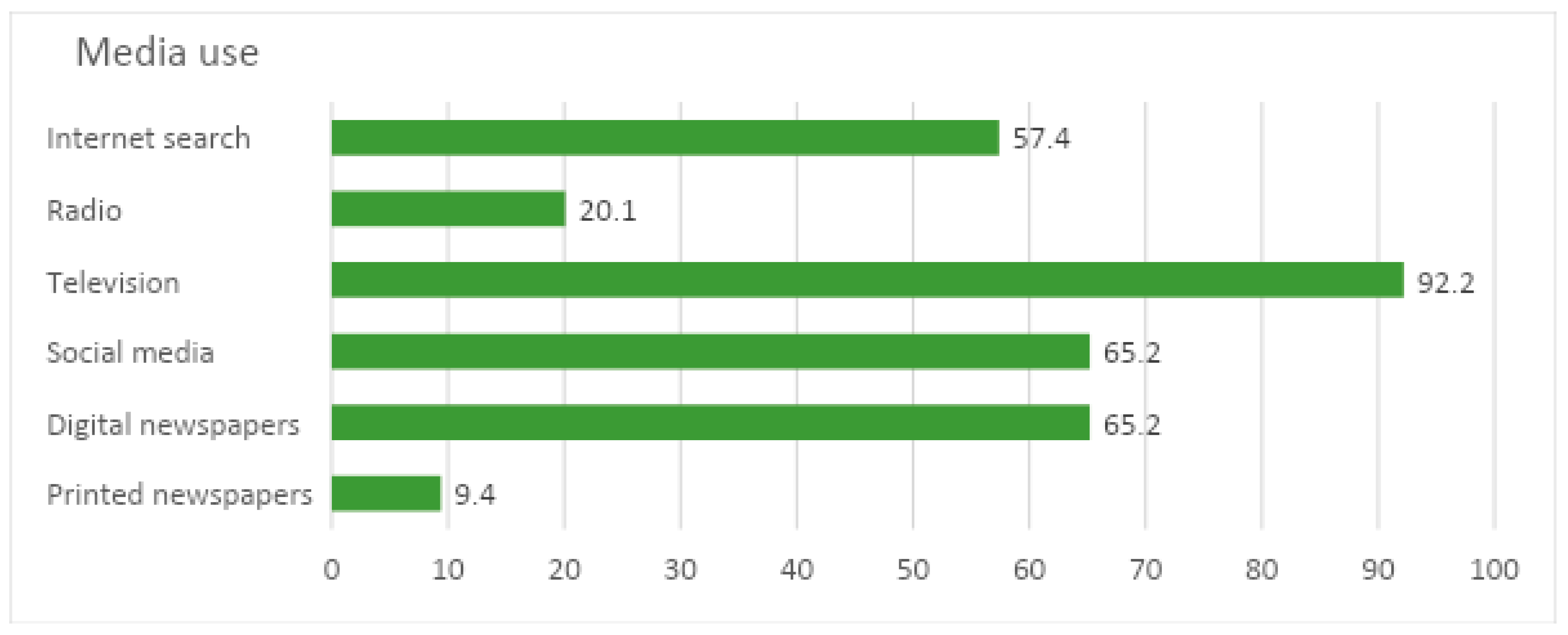

First, the data show that various types of media and platforms were used as a source of information on the pandemic. Not only the television (92%) and digital newspapers (65%) were extensively consulted in the week under review, but also social networks (65%) and internet search engines (57%) were accessed for information about the new coronavirus (

Figure 2).

Second, the importance and dependence of the media to obtain information about the COVID-19 pandemic are also supported in the answer to the question about whether “we should always see and hear the information that the media makes available to us.” This question deserves the affirmative answer of 82% of the respondents, and the most chosen option was the one that represents a greater acceptance on the scale used, revealing the degree of importance attributed to the media (

Figure 3).

If we associate these responses with the period of social confinement then in force, which drastically reduced both interpersonal contact and other forms of direct knowledge of reality, we can consider as highly plausible the initial premise, which suggests the dependence of individuals on the media system.

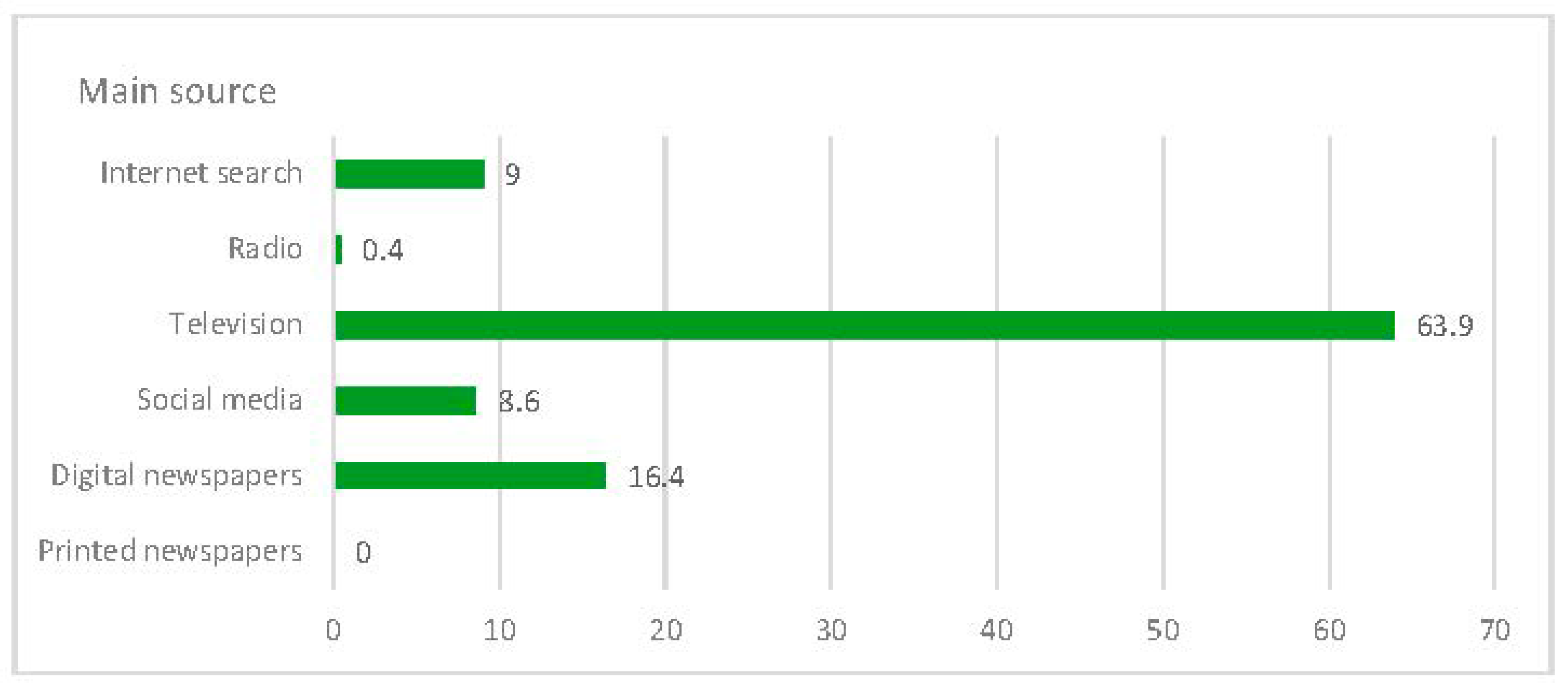

Then, we tried to find out, in a context marked by the abundance of media supply and its accessibility, which is the “

main source” of information about the COVID-19 pandemic. The results obtained are consistent with the expectations set out in previous research, and show that most people choose professional media of information as the main source of information about the pandemic—namely, television and newspapers (in digital versions and, less, on paper). In a different sense, social networks, used by 65% of individuals, are indicated as the main source of information by only 9% of respondents, half of those who choose digital newspapers as their main source and considerably less than those who are mainly informed by television (

Figure 4).

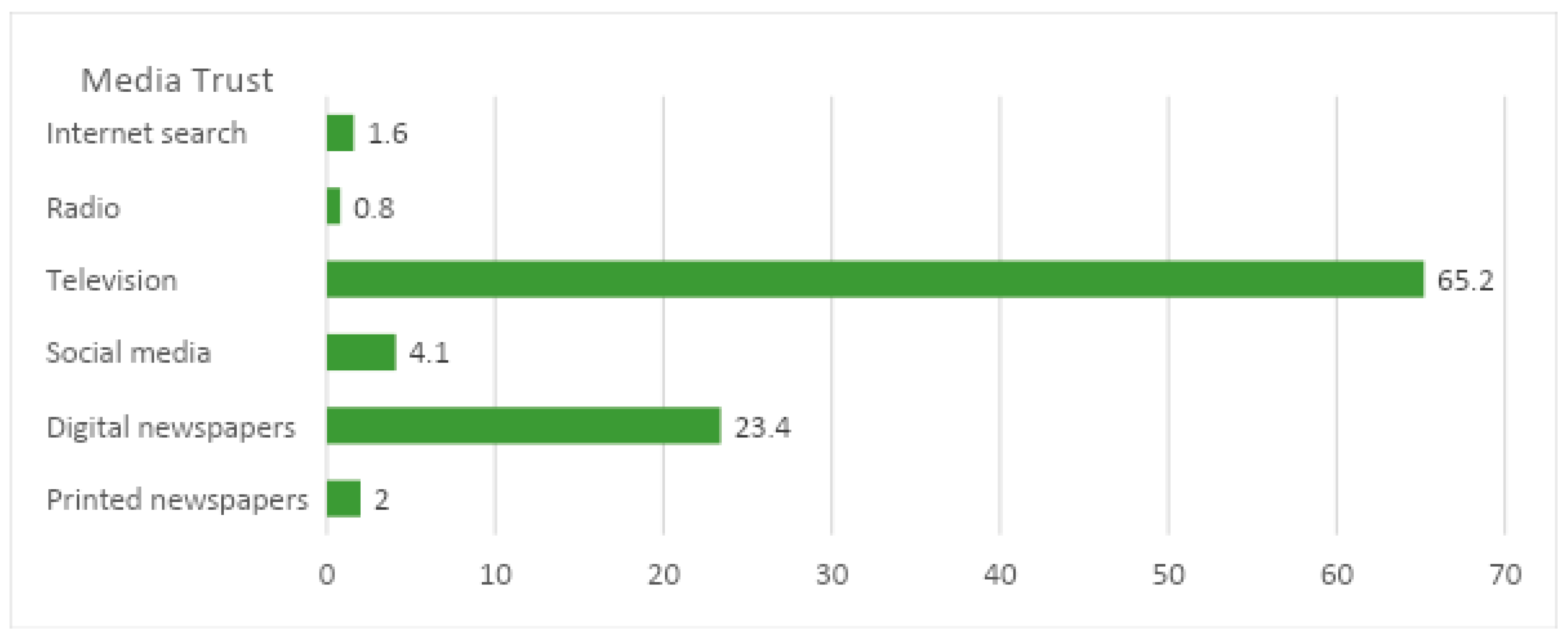

Third, we went on to assess the trust in each of the media, asking which of the media consulted to obtain information about the pandemic deserved more confidence. By the obtained data, the majority of individuals expressed strong trust in news organizations for news and information about the coronavirus, whether television (65.2%) or newspapers (print and digital, with 25.4%). Conversely, social media platforms are referred to as less reliable, as they are marked as deserving greater trust by only 4% of the surveyed individuals (

Figure 5).

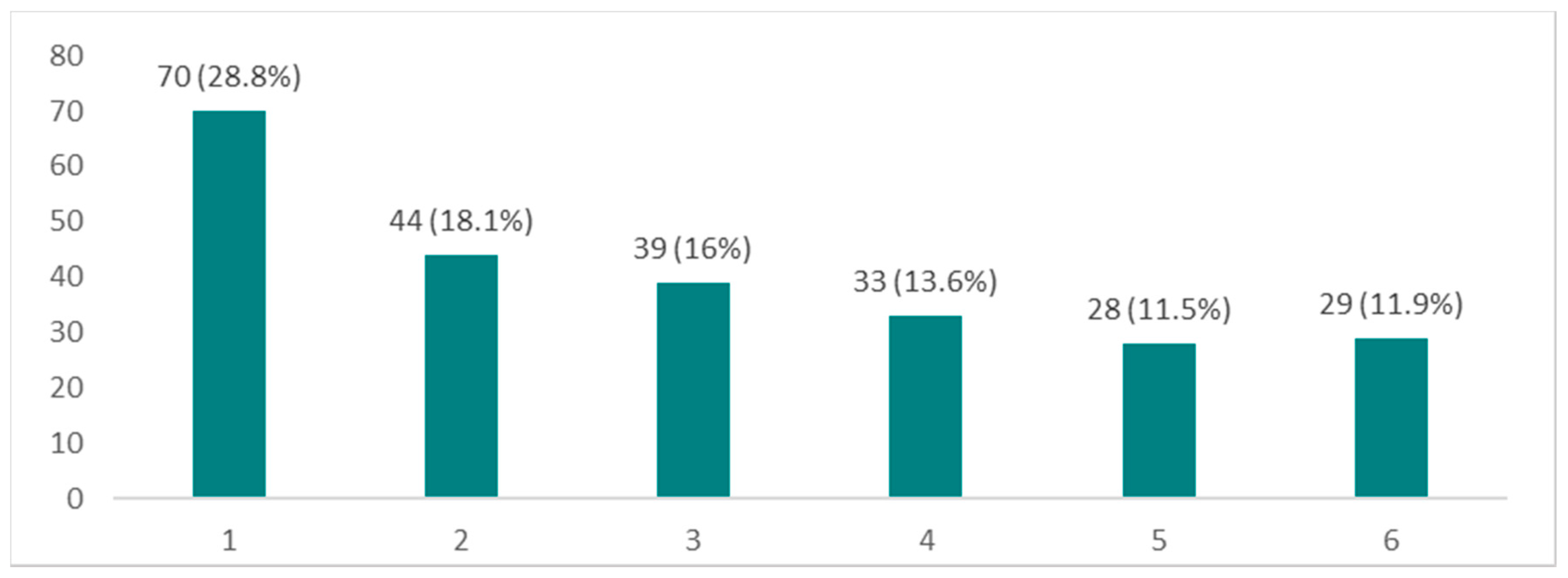

Finally, as a way of introducing the variable related to disinformation, we intend to assess the acceptance by the studied individuals of a proposition about COVID-19 widely disseminated through various media.

Christian Fuchs (

2020, p. 392) enunciated, in a recent study, a list of “false news about coronaviruses”; from this list, we selected the story stated first, regarding the origin of the virus: “The coronavirus is a Chinese biological weapon developed at the Wuhan Institute of Technology.” In our study, we sought to assess the degree of acceptance of this thesis by asking an equivalent question. The following data were obtained (

Figure 6):

The valid answers, 243, are organized into 153 disagreement responses (63%) and 90 acceptance responses (37%). We then sought to verify the existence of an association between acceptance of this theory and the main source that individuals chose to inform themselves about the pandemic (

Table 1).

Next, we performed the test Chi-squared Pearson for the variables “disinformation: biological weapon” and “main source for information about COVID-19”. The results have identified the existence of a significant relationship between the levels of acceptance of that information and the main source used (χ2 (3) = 15.093, p = 0.05).

Likewise, the same table of contingencies revealed a greater acceptance of the “conspiracy theory” by individuals who assume as the main source media designated as “accidental”, in comparison with those who actively seek information—those who indicate social networks (50%) and television (43%) have significantly higher levels of misinformation than those who reported digital newspapers (17.5%) or Internet searches (16.7). Assuming that a significant level of television consumption has an accidental dimension, these data confirm the thesis stated through the perception “news-finds-me”, that the quality of information depends on whether individuals actively seek information or are passively informed through accidental exposure.

5. Conclusions

We found that most of the results achieved by the present study are consistent with the literature on information consumption in times of uncertainty, as is the case with the current pandemic. From the outset, the obtained data allow us to assume the existence of dependence on the media concerning the need for information from individuals regarding COVID-19, illustrated by widespread consumption, the importance gave to exposure to the informative content conveyed and the diversity of consulted media, in a period marked by social confinement and by the wide reduction of other forms of interaction and direct experience of reality. This confirms our hypothesis that mainstream media are preferred by those looking for information, namely television and digital newspapers. These are also the media that individuals trust most, as advocated by the second hypothesis. The third hypothesis is also confirmed, as it appears that whoever chose conventional media as a source of information demonstrated a lower index of disinformation acceptance. On the contrary, media that are more likely to be accidentally accessed, such as social media and television, have much higher levels of acceptance of false or unconfirmed news about COVID-19. In summary, in times of pandemic, at the beginning of the state of emergency, mostly confined, the individuals questioned consumed information from all available sources (television, social networks, digital newspapers and the Internet), but attributed greater credibility to conventional information media—television and newspapers. Social networks, although regularly consulted, have been trusted by a minority. We can thus suggest the existence of elements that point to digital literacy skills—when verifying the attribution of a hierarchy in information—with journalism obtaining greater credibility compared to that conveyed by social networks.

We point out, in this regard, some limitations of the present study. First, the non-segmentation of content present in social media (where anonymous rumors coexist side by side with publications from mainstream media) and on television (where the diversity of content, information, opinion or entertainment also coexists). Second, social media themselves have developed credible information mechanisms about the pandemic, supported by rigorous information and automatically highlighted in each user’s feed. At the same time, they have created mechanisms to scrutinize and report false information, collaborating actively in combating the dangers of

infodemic. WHO, for its part, started a dedicated messaging service on WhatsApp and Facebook in Arabic, English, French, Hindi, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese to transmit security and correct information about the pandemic (

Sahni and Sharma 2020). The effects of these actions were also not considered by the present study. Finally, the demographic data collected (age and gender) did not make it possible to identify significant differences in the use of the various media, and the confidence attributed to them, so it would be useful to consider other untested variables (education, income, among others). This limitation is highlighted from the results of recent studies (

Nielsen et al. 2020), which reveal that people with low levels of formal education have a higher probability of dependence on social media applications to obtain information on the coronavirus, also being more likely to incorrectly answer simple questionnaires about COVID-19.

It is concluded that the dependence on the media, which dates back to the era of mass communication, remains in a situation of a health crisis, although we now live in an ecosystem of informational abundance and that registers the consumption of hybrid media. Despite the use of social networks, it is concluded that citizens continue to maintain confidence in traditional information media regarding access to quality information. Thus, the high consumption of information from all the media, which this study identified, reaffirms the relevance of the theory of media dependence, as a way of obtaining information in contemporary societies, marked by unprecedented levels of media coverage.

One of the important conclusions of this study was thus that those who actively seek to inform themselves through journalistic mainstream media consider them more reliable—a perception that proves to be adequate, because these citizens demonstrate to be better informed and are less likely to believe in disinformation. It is noted, from here on, a greater danger to citizenship, and that the data of this study confirmed the greater susceptibility to false news by the individuals who attribute greater credibility to the information they find on social media. As shown above, because they satisfy their information needs through social networks, these individuals tend to judge themselves well informed and to do without the consumption of other media. This results in a practical implication: these perceptions point to the importance (and the need) of media literacy actions that provide individuals with mechanisms for assessing the credibility of information sources.

We conclude with a final perception taken from the present study: in a media ecosystem that over the past years has been plagued by progressive crisis of credibility, the current pandemic has shown that journalism continues in what is still its natural place and that the credibility of the media is a very complex issue that needs further investigation. Despite the uncertainty and contradictions associated with it, which this article does not intend to address, we believe that in journalism still resists the ability to fulfill the “vote of confidence” that society has granted it.