The Value of Recreational Ecosystem Services in India †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Travel Cost Method

2.3.2. Econometric Model

2.3.3. Consumer Surplus

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

References

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; De Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Board. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Wetlands and Water Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, U.; Muradian, R.; Brander, L.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Martín-López, B.; Verma, M.; Armsworth, P.; Christie, M.; Cornelissen, H.; Eppink, F.; et al. The economics of valuing ecosystem services and biodiversity. In Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 183–256. [Google Scholar]

- Ninan, K.N.; Kontoleon, A. Valuing forest ecosystem services and disservices—Case study of a protected area in India. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, M.; Pettenella, D.; Boscolo, M.; Kanti Barua, S.; Animon, I.; Matta, R. Valuing Forest Ecosystem Services: A Training Manual for Planners and Project Developers; Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Li, H.; Yue, S.; Huang, K. A conceptual decision-making for the ecological base flow of rivers considering the economic value of ecosystem services of rivers in water shortage area of Northwest China. J. Hydrol. 2019, 578, 124126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Börner, J.; Shively, G.; Wyman, M. Safety nets, gap filling and forests: A global-comparative perspective. World Dev. 2014, 64, S29–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, M.; Schaap, B. Forest Ecosystem Services. In Proceedings of the United Nations Forum on Forests, New York, NY, USA, 26–30 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Di Girolami, E.; Arts, B. Environmental Impacts of Forest Certifications; Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group, Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W. The Economic Value of Forest Ecosystems. Ecosyst. Health 2001, 7, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, A.S.; Lertzman, K.P.; Gustafsson, L. Biodiversity and ecosystem services in forest ecosystems: A research agenda for applied forest ecology. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Wunder, S. Exploring the Forest—Poverty Link; CIFOR Occasional Paper No. 40; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2003; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, C.; Shackleton, S. The importance of non-timber forest products in rural livelihood security and as safety nets: A review of evidence from South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2004, 100, 658–664. [Google Scholar]

- Paumgarten, F. The role of non-timber forest products as safety-nets: A review of evidence with a focus on South Africa. GeoJournal 2005, 64, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Jagger, P.; Babigumira, R.; Belcher, B.; Hogarth, N.J.; Bauch, S.; Börner, J.; Smith-Hall, C.; Wunder, S. Environmental income and rural livelihoods: A global-comparative analysis. World Dev. 2014, 64, S12–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.; Blackman, D. A guide to understanding social science research for natural scientists. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Negandhi, D.; Khanna, C.; Edgaonkar, A.; David, A.; Kadekodi, G.; Costanza, R.; Gopal, R.; Bonal, B.S.; Yadav, S.P.; et al. Making the hidden visible: Economic valuation of tiger reserves in India. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badola, R.; Hussain, S.A.; Mishra, B.K.; Konthoujam, B.; Thapliyal, S.; Dhakate, P.M. An assessment of ecosystem services of Corbett Tiger Reserve, India. Environment 2010, 30, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, M. Economics of Urban Ecosystem Services: A Case Study of Bangalore, Monograph; Institute for Social and Economic Change: Bangalore, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gantioler, S.; D’Amato, D. Cultural services and related goods. In Social and Economic Benefits of Protected Areas: An Assessment Guide; Earthscan Publishers: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, R.S.; Alkemade, R.; Braat, L.; Hein, L.; Willemen, L. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, J.; Soares-Filho, B.; Costa, M.H.; Oliveira, U.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Pires, G.F.; Olieria, A.; Rajao, R.; May, P.; Van de Hoff, R.; et al. Spatially explicit valuation of the Brazilian Amazon Forest’s Ecosystem Services. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashaw, T.; Tulu, T.; Argaw, M.; Worqlul, A.W.; Tolessa, T.; Kindu, M. Estimating the impacts of land use/land cover changes on Ecosystem Service Values: The case of the Andassa watershed in the Upper Blue Nile basin of Ethiopia. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhen, L.; Zhang, L. Dynamic changes in the value of China’s ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.M.; Bandyopadhyaya, S.; Kumar, L.; Bedamatta, S. Economic Valuation of Landscape Level Wetland Ecosystem and Its Services in Little Rann of Kachchh, Gujarat; The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity India Initiative, GIZ India; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH: Bonn/Eschborn, Germany, 2016; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Badola, R. People and protected areas in India. Unsalvya 1999, 199, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Da Costa, V. Recreational Value of Coastal and Marine Ecosystems in India: A Partial Estimate; Working Paper 124; Madras School of Economics: Tamil Nadu, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mohandas, T.V.; Remadevi, O.K. A study on tourist visitations in protected areas of Central Western Ghats in Karnataka. Indian For. 2011, 137, 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Gera, M.; Yadav, A.K.; Bisht, N.S.; Giresh, M. Valuation of recreational benefits from Valley of Flowers National Park. Indian For. 2008, 134, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Panchamukhi, P.R.; Trivedi, P.; SKumar, A.; Sharma, P. National Resource Accounting in Karnataka: A Case Study of the Land & Forestry Sector (Excluding Mining); Central Statistical Organisation, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, C.; Singh, R.; David, A.; Edgaonkar, A.; Negandhi, D.; Verma, M.; Costanza, R.; Kadekodi, G. Economic Valuation of Tiger Reserves in India a Value + Approach; Indian Institute of Forest Management: Madhya Pradesh, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, M. Valuation of Ecosystem Services and their implications for accounting for natural capital in Karnataka. Aarthika Charche FPI J. Econ. Gov. 2020, 5, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Heagney, E.C.; Rose, J.M.; Ardeshiri, A.; Kovac, M. The economic value of tourism and recreation acrossa large protected area network. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M. Estimating the economic value of ice climbing in Hyalite Canyon: An application of travel cost count data models that account for excess zeors. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, I.J.; Binner, A.; Day, B.; Fezzi, C.; Rusby, A.; Smith, G.; Welters, R. United Kingdom: Paying for Ecosystem Services in the Public and Private Sectors; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, H. Demand for Eco-Tourism: Estimating Recreational Benefits from the Margalla Hills National Park in Northern Pakistan; Working Paper No 5-04; SANDEE: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Timah, P.N. Non-Market Valuation of Beach Recreation Using the Travel Cost Method (TCM) in the Context of the Developing World; Department of Economics, Saint Louis University: Uppsala, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, M.A.; Wratten, S.D. The role of ecosystem disservices in pest management. In Environmental Pest Management: Challenges for Agronomists, Ecologists, Economists and Policymakers; John Weily and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, M.; Woltering, M. Assessing and valuing the recreational ecosystem services of Germany’s national parks using travel cost models. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, C.M.; Cook, A. The recreational value of Lake McKenzie, Fraser Island: An application of the travel cost method. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ricketts, T.H.; Kremen, C.; Carney, K.; Swinton, S.M. Ecosystem services and dis-services to agriculture. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 64, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, J.; Dyack, B. Valuing recreation in the Coorong, Australia, with travel cost and contingent behaviour models. Econ. Rec. 2011, 87, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.R.; Wattage, P.; Pascoe, S. Recreational benefits from a marine protected area: A travel cost analysis of Lundy. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourkolias, C.; Skiada, T.; Mirasgedis, S.; Diakoulaki, D. Application of the travel cost method for the valuation of the Poseidon temple in Sounio, Greece. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharali, A.; Mazumder, R. Application of travel cost method to assess the pricing policy of public parks: The case of Kaziranga National Park. J. Reg. Dev. Plan. 2012, 1, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, M. Economic Value of Regulating Ecosystem Services: A Comprehensive at the Global Review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultural Ecosystem Services | Examples of Related Goods and Services |

|---|---|

| Opportunities for recreation and tourism | Hiking, camping, nature walks, jogging, winter sports, wild watching, horse riding, hunting, etc. |

| Aesthetic values | Enjoyment of rural, unique and colorful landscapes, individual habitats and species, and tranquility supporting mental well-being. |

| Inspiration for the art, science, and technology | Writing, painting, design, documentaries, movies, engineering materials, and architecture |

| Information for education and research | Education trips by schools and other groups; employee training; research related to ecosystem function, publications and patents. |

| Spiritual and religious experience | Natural and built sacred places, philosophy and faith; support to mental well-being. |

| Cultural identify and heritage | Landscape and habitats formed by human activities, species of spiritual importance, traditional and indigenous knowledge |

| Nagarhole National Park | Nandi Hills | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–40 | 78 | 66.66 |

| 41–60 | 20 | 29.33 |

| Above 60 | 1.3 | 4 |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 1.3 | 6 |

| Primary | 2 | 18 |

| Secondary | 24.7 | 70 |

| University level | 72 | 5.33 |

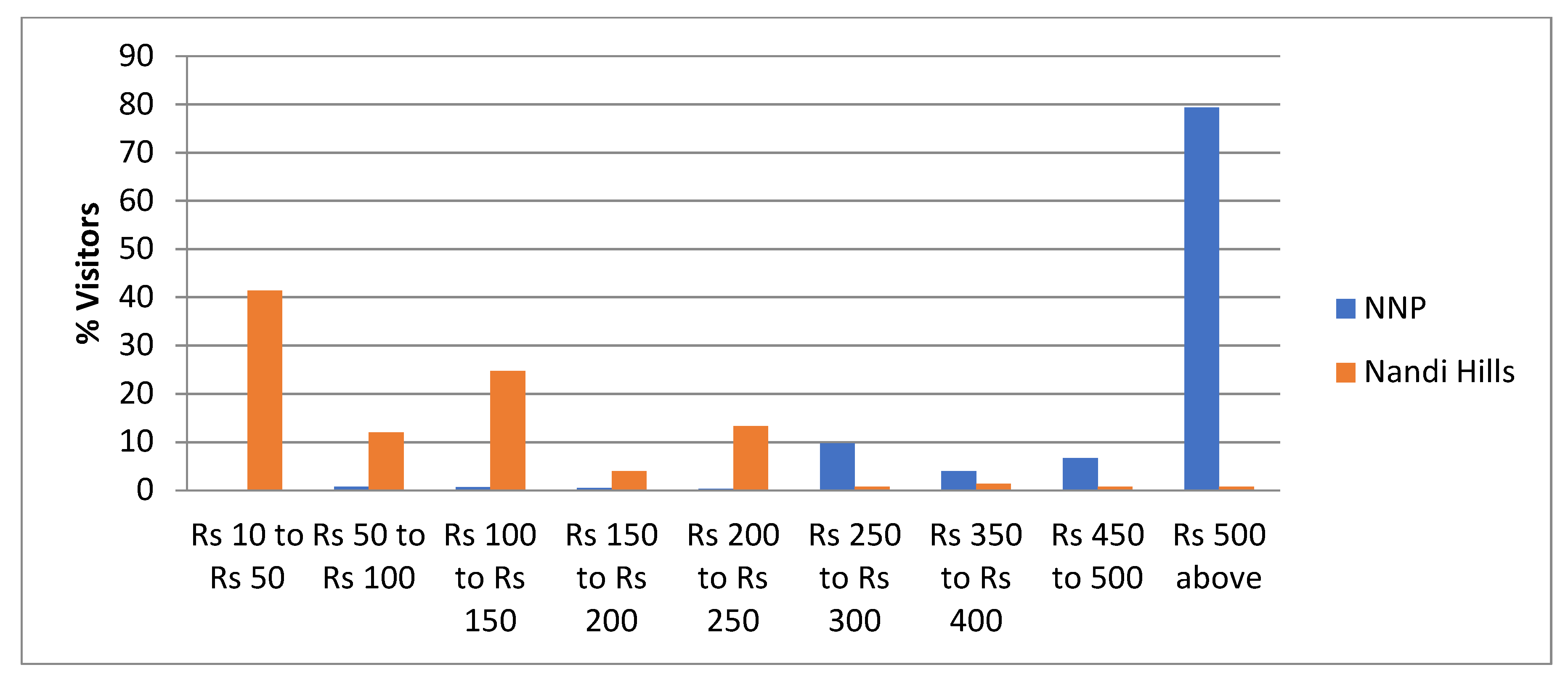

| Household Income | ||

| Rs 10,000–Rs 25,000 | 13.3 | 14.7 |

| Rs 25,000–Rs 50,000 | 78.7 | 47.3 |

| Rs 50,000–Rs 75,000 | 8 | 38 |

| Rs 75,000 and above | 0 | 0 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 8.1 | 44.67 |

| Married | 86.7 | 54 |

| Widow | 0 | 1.3 |

| Household Size | ||

| 2 to 5 | 80 | 75.3 |

| 6 to 10 | 17.3 | 20 |

| Above 10 | 2.7 | 5.7 |

| Variables | Coefficient t-Statistics) NNP | Coefficient (t-Statistics) Nandi Hills |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.980 (2.761) | 1.823 (4.037) |

| Travel Cost | −1.014 × 10−5 (−1.716) ** | −0.247 (−3.074) *** |

| Age | −0.009 (−2.136) ** | −0.175 (−2.212) ** |

| Marital Status | 0.113 (1.110) | 0.431 (2.301) |

| Household size | 0.060 (1.264) | 0.049 (2.386) |

| Educational status | −0.017 (−1.285) | 0.983 (2.487) |

| Residential location | 0.139 (1.969) ** | 0.140 (1.750) * |

| Household Income | 3.880 × 10−6 (2.108) ** | 0.149 (1.846) * |

| Quality of the park | −0.47 (−1.258) | −0.32 (−1.130) |

| R2 | 14.0 | 12.9 |

| F-Statistics | 2.837 | 2.273 |

| Components | Nandi Hills Value in (Rs) | Nagarhole National Park |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Average Consumer Surplus | Rs 247 | Rs 557.33 |

| Total Economic Benefits | Rs. 2.47 billion | Rs 55.8 million |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balasubramanian, M. The Value of Recreational Ecosystem Services in India. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2021, 3, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECF2020-08030

Balasubramanian M. The Value of Recreational Ecosystem Services in India. Environmental Sciences Proceedings. 2021; 3(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECF2020-08030

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalasubramanian, Muniyandi. 2021. "The Value of Recreational Ecosystem Services in India" Environmental Sciences Proceedings 3, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECF2020-08030

APA StyleBalasubramanian, M. (2021). The Value of Recreational Ecosystem Services in India. Environmental Sciences Proceedings, 3(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECF2020-08030