Physicochemical Properties and Diatom Diversity in the Sediments of Lake Batur: Insights from a Volcanic Alkaline Ecosystem

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

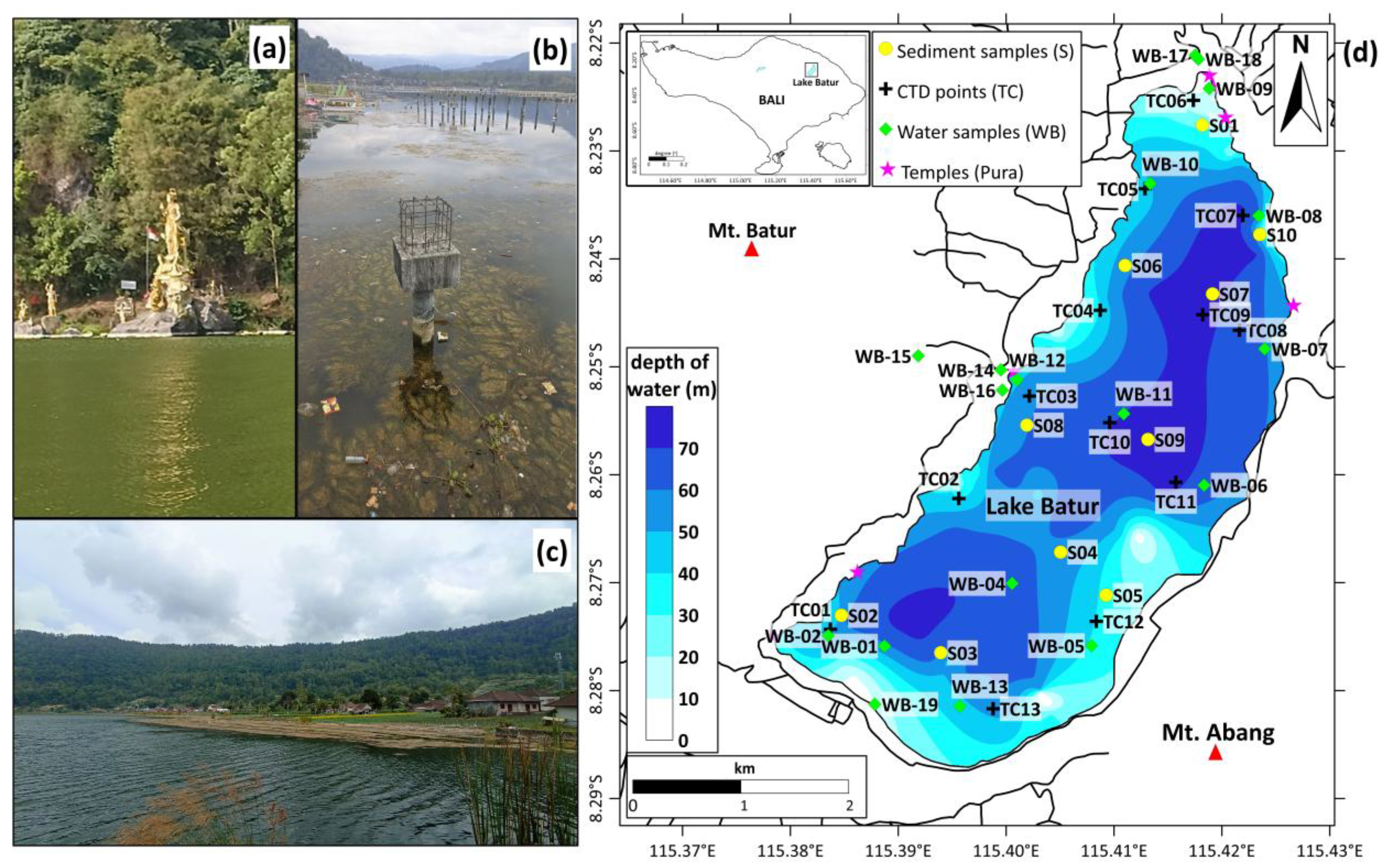

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Measurement of Ecological Parameters, Data Treatment, and Diatom Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

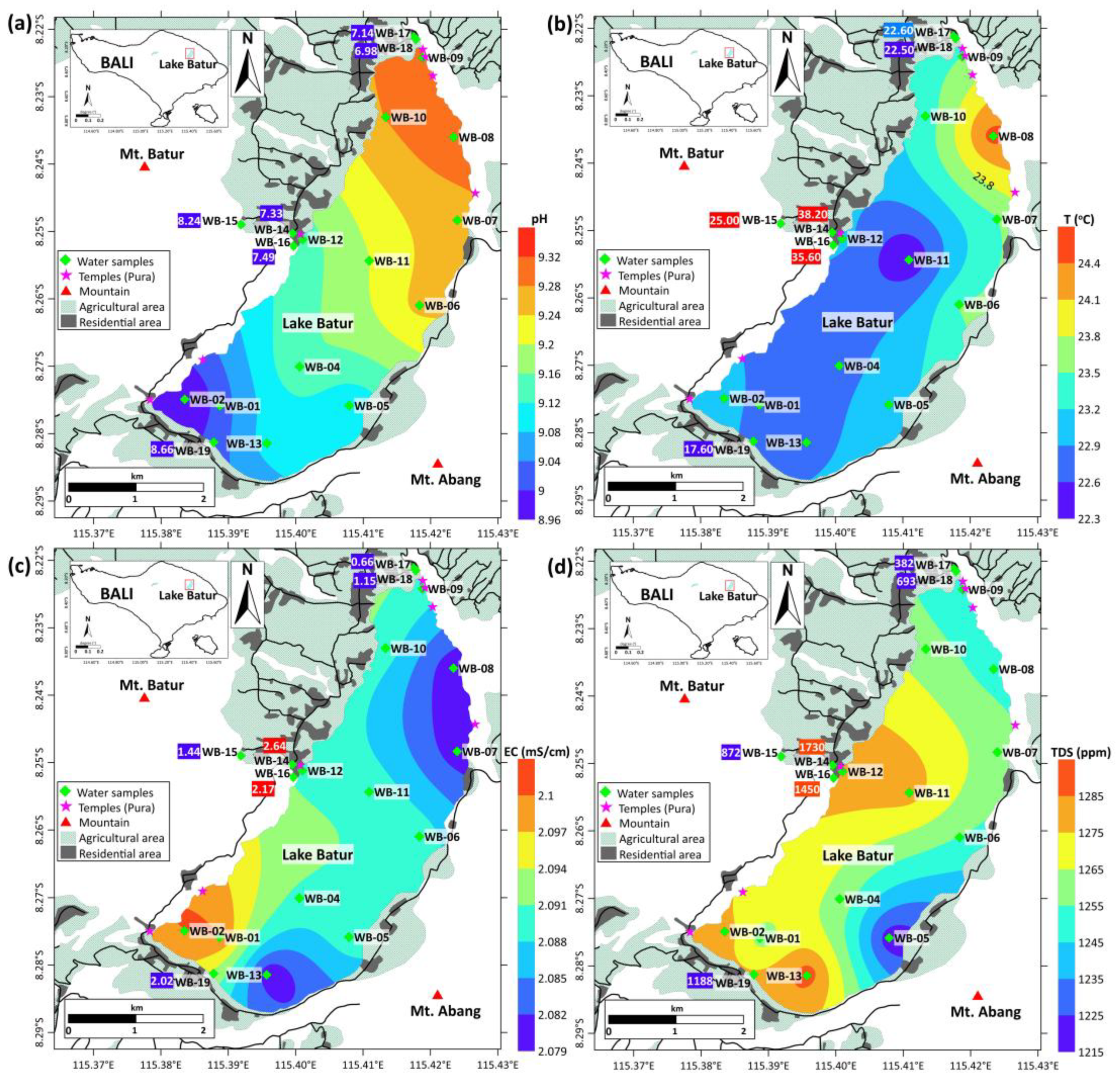

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters and Ion Concentration of Surface Water

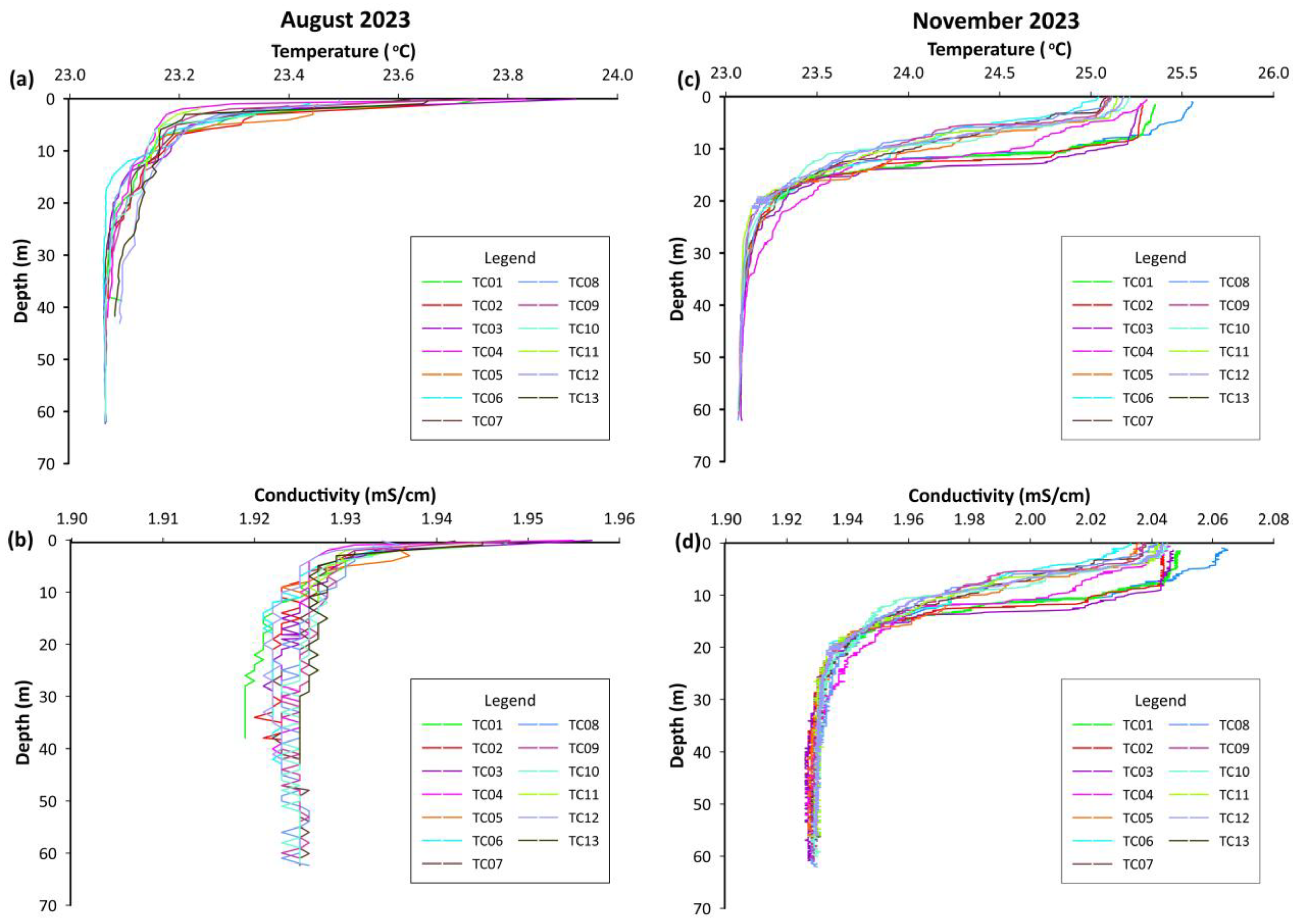

3.2. Temperature and Conductivity Profiles with Depth

3.3. Diatom Assemblages in Surface Sediments

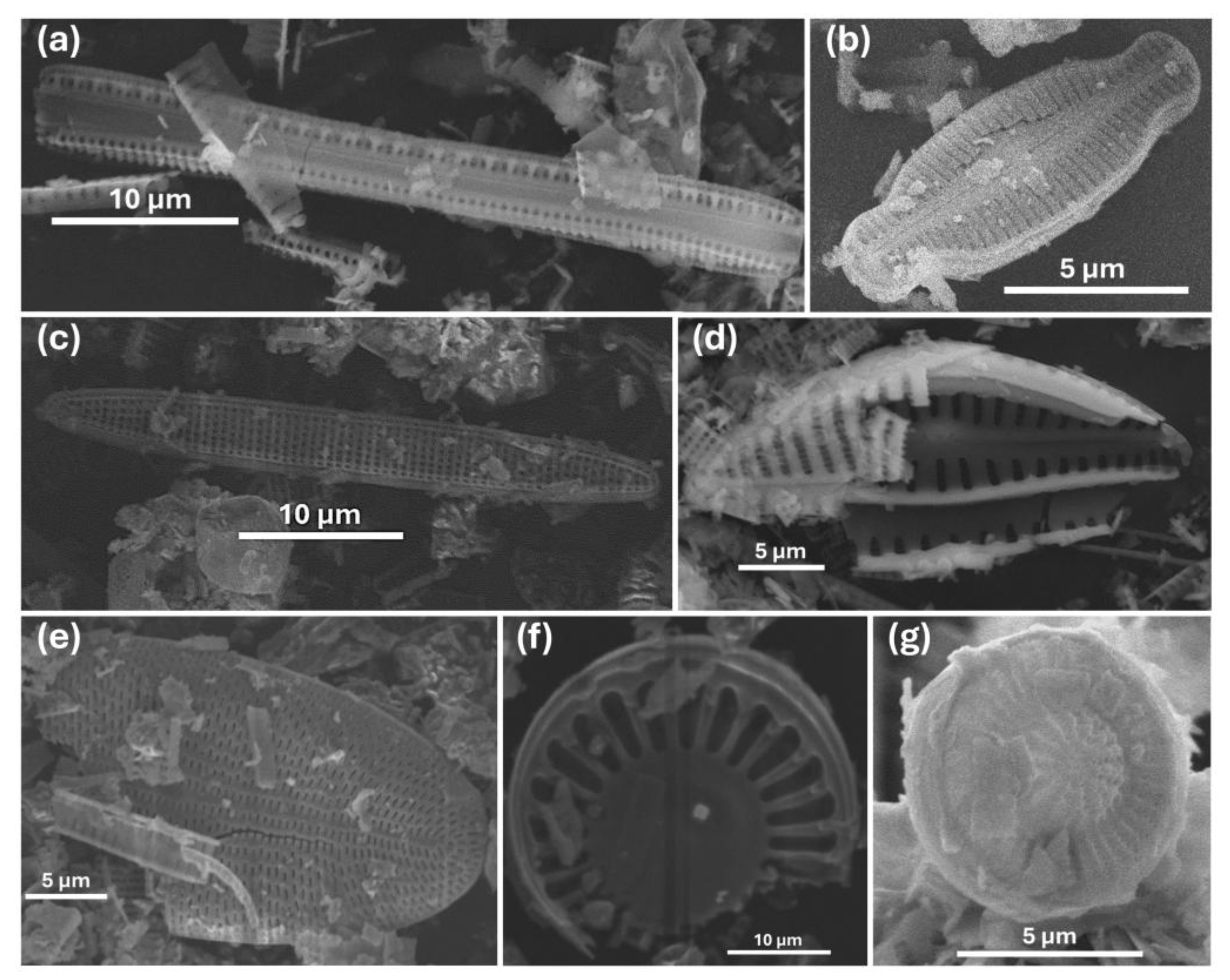

- Discostella sp. was observed in Lake Batur with frustule diameters ranging from 7.83 to 14.39 µm (Figure 4f,g). The observed morphology shows a strong similarity to Discostella cf. stelligera Houk and Klee, 2004. This genus is commonly found in freshwater environments and has been widely reported from various lacustrine systems [17].

- Ulnaria sp. was identified with frustule lengths exceeding 62.53 µm and widths of approximately 4.97 µm. The observed morphology is consistent with members of the Ulnaria acus group (Kütz.) Compère, 2001, which is typically associated with moderately alkaline and eutrophic water bodies. This genus is often linked to nutrient-rich environments and has been used as a bioindicator of elevated nutrient conditions [35].

- Denticula sp. exhibited frustule lengths ranging from 17.08 to 41.72 µm and widths between 2.58 and 4.68 µm. The observed specimens show morphological similarities to Denticula cf. tenuis Kütz., 1844. However, species-level identification remains tentative. The genus Denticula is commonly reported from carbonate-rich freshwater environments with moderate conductivity and elevated alkalinity [36].

- Simonsenia sp. was identified with a frustule length of 9.91 µm and a width of 2.49 µm. Due to limited diagnostic features observed in SEM images, species-level identification could not be resolved. This genus is frequently reported from nutrient-enriched waters and is commonly associated with eutrophic conditions [22].

- Karayevia sp. was detected with a frustule length of approximately 11.87 µm. Although the morphology shows similarities to Karayevia amoena group Round et Bukht. ex Round, 1998, species-level identification was not assigned due to the conservative taxonomic approach applied in this study. Members of this genus are typically associated with alkaline environments characterized by relatively high pH and moderate conductivity [31].

- Encyonema sp. was observed with frustule lengths ranging from 21.62 to 29.53 µm and widths between 7.48 and 8.31 µm. The morphology is consistent with the Encyonema montana group Kütz, 1833. However, identification was retained at the genus level. This genus commonly occurs in alkaline freshwater systems with moderate conductivity and has previously been reported from lakes in Bali, including Lake Buyan [28,31].

- Pseudostaurosira sp. was identified with dimensions of approximately 4.6 µm in length and 4.4 µm in width. Due to limited morphological resolution, further taxonomic refinement at the species level was not possible. This genus is characterized by its distinctive frustule structure and is commonly found in freshwater sediments [31].

- Diploneis sp. was observed with a frustule length of approximately 22.36 µm and a width of 9.27 µm. This genus is generally associated with oligotrophic freshwater environments and is typically present in low abundance. Diploneis is often considered indicative of low-nutrient conditions [37].

- Cymbella sp. was observed with a frustule length greater than 20.88 µm and a width of approximately 6.56 µm. Although species-level identification could not be determined, Cymbella is a widespread genus commonly reported from a variety of freshwater habitats [31].

- Cocconeis sp. was observed with frustule lengths ranging from 31.74 to 33.09 µm and widths between 13 and 17.76 µm. The observed specimens show similarities to Cocconeis cf. klamathensis group Ehrenberg, 1837. However, special-level identification remains tentative. The genus Cocconeis is commonly reported from oligotrophic lakes and moist subaerial habitats and has also been documented in freshwater systems in Bali, including Lake Buyan [28,31].

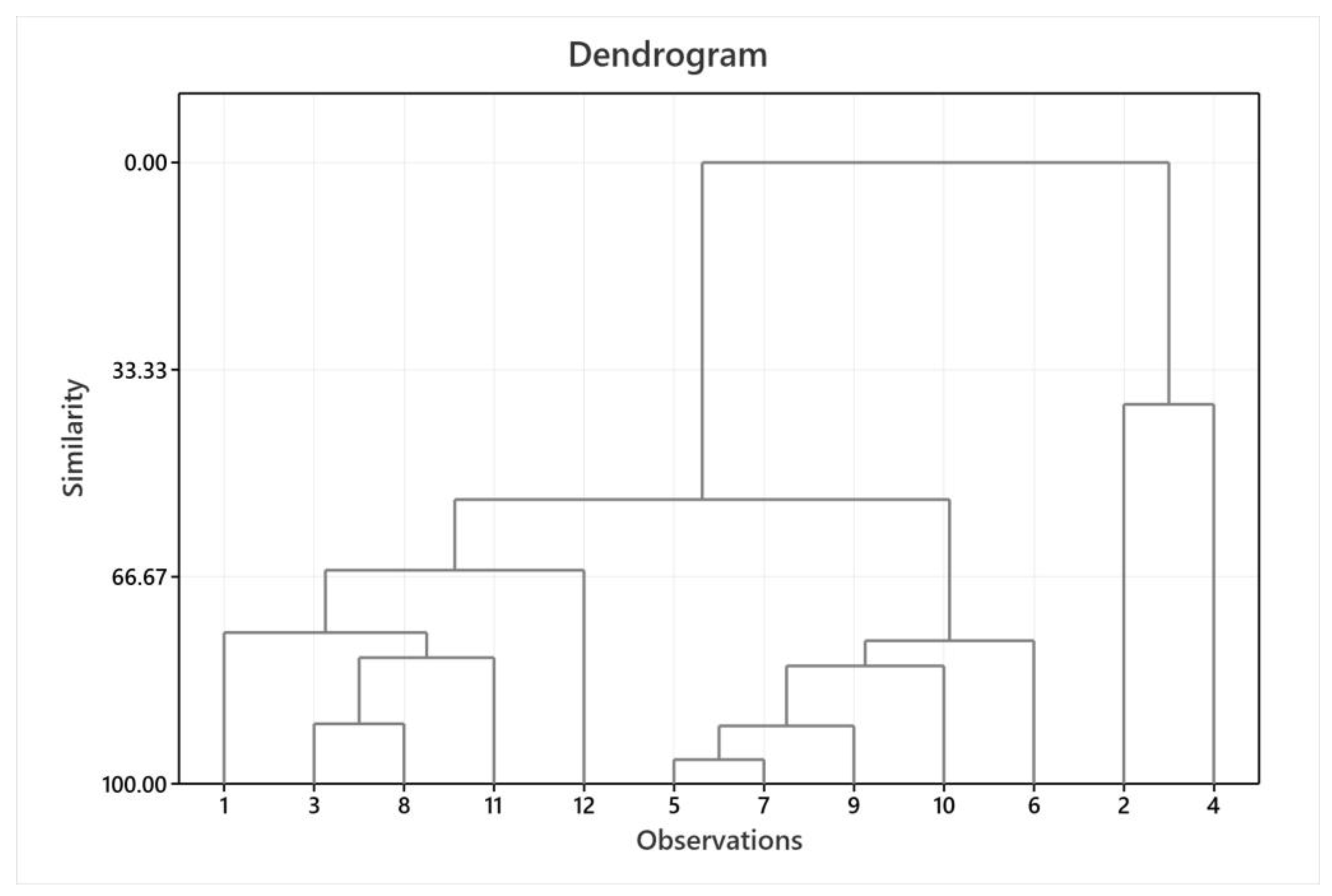

3.4. Spearman Correlation and HCA

4. Discussion

4.1. Physicochemical Characteristics of Surface Water

4.2. Vertical Thermal and Conductivity Structure

4.3. Nutrient Enrichment, Diatom Assemblages, and Ecological Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marchetto, A.; Ariztegui, A.; Brauer, A.; Lami, A.; Mercuri, A.M.; Sadori, L.; Vigliotti, L.; Wulf, S.; Guilizzoni, P. Volcanic Lake Sediments as Sensitive Archives of Climate and Environmental Change. In Volcanic Lakes, Advances in Volcanology; Rouwet, D., Christenson, B., Tassi, F., Vandemeulebrouck, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lukman, L.; Hidayat, H.; Subehi, L.; Dina, R.; Mayasari, N.; Melati, I.; Sudriani, Y.; Ardianto, D. Pollution loads and its impact on Lake Toba. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 299, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wantasen, S.; Luntungan, J. Water Resources Management of Lake Tondano in North Sulawesi Province. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 256, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makmur, S.; Muthmainnah, D.; Subagdja. Fishery activities and environmental condition of Maninjau Lake, West Sumatra. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 564, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batur Global Geopark. Available online: https://geoparksnetwork.id/geopark-global (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Harlianti, U.; Bijaksana, S.; Iskandar, I.; Lubis, R.F.; Venkateshwarlu, M.; Satyakumar, A.V.; Suryanata, P.B.; Fajar, S.J.; Suandayani, N.K.T.; Ibrahim, K. Magnetic properties of surface sediment in a closed alkaline volcanic lake: A case study from Lake Batur, Bali, Indonesia. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, I.M.; Redana, I.W.; Dharma, I.G.B.S.; Yana, A.A.G.A. Community-based erosion control model in Batur Lake zone. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 276, 04008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irdhawati; Manuruang, M.; Reichelt-Brushett, A. Trace metals and nutrients in lake sediments in the Province of Bali, Indonesia: A baseline assessment linking potential sources. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2021, 72, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suandayani, N.K.T.; Harlianti, U.; Fajar, S.J.; Suryanata, P.B.; Ibrahim, K.; Bijaksana, S.; Dahrin, D.; Iskandar, I. Religious activities and their impacts on the surface sediments of two lakes in Bali, Indonesia: A case study from Lake Buyan and Lake Tamblingan. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2023, 11, 00140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkowska, Ż.; Ruman, M.; Lehmann, S.; Matysik, M.; Absalon, D. The Specific Nature of Chemical Composition of Water from Volcanic Lakes Based on Bali Case Study. APCBEE Procedia 2014, 10, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkowska, Ż.; Wolska, L.; Łęczyński, L.; Ruman, M.; Lehmann, S.; Kozak, K.; Matysik, M.; Absalon, D. Estimating the Impact of Inflow on the Chemistry of Two Different Caldera Type Lakes Located on the Bali Island (Indonesia). Water 2015, 7, 1712–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, D.; Sentosa, A.A.; Tjahjo, D.W.H. Kajian Kualitas Perairan dan Potensi Produksi Sumber Daya Ikan di Danau Batur, Bali (Study of Water Quality and Production Potential of Fish Resources in Lake Batur, Bali). In Proceedings of the 6th National Limnology Seminar, Bogor, Indonesia, 16 July 2012. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

- Sukmawati, N.M.H.; Pratiwi, A.E.; Rusni, N.W. Water Quality of Batur Lake Based on Physico-chemical Parameters and NSFWQI. WICAKSANA J. Lingkung. Dan Pembang. 2019, 3, 53–60. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Mustiatin; Iskandar, I.; Anggayana, K.; Ariantana, I.K.; Suryantini; Notosiswoyo, S. An Overview on Bali’s Largest Volcanic Lake: Detecting the Source of The Lake Water Using Surface Hydrogeochemical Approach. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Earth Science and Technology, Fukuoka, Japan, 1–2 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Suryono, T.; Nomosatriyo, S.; Mulyana, E. Tingkat Kesuburan Danau—Danau di Sumatera Barat dan Bali (Fertility Levels of Lakes in West Sumatra and Bali). LIMNOTEK Trop. Inland Waters Indones. 2008, 15, 99–111. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Han, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, B.; Li, Y.; Pan, K. The Structure of the Seasonal Benthic Diatom Community and Its Relationship with Environmental Factors in the Yellow River Delta. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 784238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, E.S.; Kulikovskiy, M.S. Centric diatoms from Vietnam reservoirs with description of one new Urosolenia species. Nova Hedwig. Beih. 2014, 143, 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger, B.J.; Cocquyt, C.; O’Reilly, C.M. Benthic diatoms as indicators of eutrophication in tropical streams. Hydrobiologia 2006, 573, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitner, M.; Poulíčková, A. Littoral diatoms as indicators for the eutrophication of shallow lakes. Hydrobiologia 2003, 506, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Rondón, C.A.; Catalan, J. Diatom as indicators of the multivariate environment of mountain lakes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 135517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzal-Almeida, S.; Bartozek, E.C.R.; Bicudo, D.C. Homogenization of diatom assemblages is driven by eutrophication in tropical reservoir. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 288, 117778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, G.; Fernández, M.R. Diatoms as Indicators of Water Quality and Ecological Status: Sampling, Analysis and Some Ecological Remarks. In Ecological Water Quality-Water Treatment and Reuse; Voudouris, K., Ed.; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Adjovu, G.E.; Stephen, H.; Ahmad, S. Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Key Water Quality Parameters in a Thermal Stratified Lake Ecosystem: The Case Study of Lake Mead. Earth 2023, 4, 461–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaafri, I.; Seghir, K.; Valles, V.; Barbiero, L. Regional Hydro-Chemistry of Hydrothermal Springs in Northeastern Algeria, Case of Guelma, Souk Ahras, Tebessa and Khenchela Regions. Earth 2024, 5, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.S.; Hossain, M.E.; Majed, N. Assessment of Physicochemical Properties and Comparative Pollution Status of the Dhaleshwari River in Bangladesh. Earth 2021, 2, 696–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheller, G.E.; Varne, R. Genesis of dacitic magmatism at Batur volcano, Bali, Indonesia: Implications for the origins of stratovolcano calderas. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1986, 28, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagami, K.; Kubota, J.; Setiawan, B.I. Sustainable Water Management; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto, Y.; Li, X.; Yasuda, Y.; Okamura, M.; Yamada, K.; Kashima, K. The Holocene environmental changes in southern Indonesia reconstructed from highland caldera lake sediment in Bali Island. Quat. Int. 2015, 374, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayane, I.; Shimmi, O.; Winaya, P.D. Physical and religious background of subak in Bali. In Water Cycle and Water Use in Bali Island, 1st ed.; Kayane, I., Ed.; Institute of Geosciences, Tsukuba University: Ibaraki, Japan, 1992; pp. 229–247. [Google Scholar]

- Pengelolaan Ekosistem Danau Batur (Lake Batur Ecosystem Management). Available online: http://ppebalinusra.menlhk.go.id/pengelolaan-ekosistem-danau-batur/ (accessed on 7 May 2024). (In Indonesian).

- Spaulding, S.A.; Potapova, M.G.; Bishop, I.W.; Lee, S.S.; Gasperak, T.S.; Jovanoska, E.; Furey, P.C.; Edlund, M.B. Diatoms.org: Supporting taxonomists, connecting communities. Diatom Res. 2021, 36, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamsher, S.E.; Graeff, C.L.; Stepanek, J.G.; Kociolek, J.P. Frustular morphology and polyphyly in freshwater Denticula (Bacillariophyceae) species, and the description of Tetralunata gen. nov. (Epithemiaceae, Rhopalodiales). Plant Ecol. Evol. 2014, 147, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Drinking Water Specifications. Available online: https://cpcb.nic.in/who-guidelines-for-drinking-water-quality/ (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Penyelenggaraan Perlindungan dan Pengelolaan Lingkungan Hidup (Environmental Protection and Management Authority). Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/161852/pp-no-22-tahun-2021 (accessed on 7 May 2024). (In Indonesian).

- Lange-Bertalot, H.; Ulrich, S. Contributions to the taxonomy of needle-shaped Fragilaria and Ulnaria species. Lauterbornia 2014, 78, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Diatoms of North America. Available online: https://diatoms.org/genera/denticula (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- Lange-Bertlot, H.; Fuhrmann, A. Diploneis lecohuiana sp. nov., D. fereparma sp. n., and D. parma Cleve: Rare diatoms (Bacillariophyta) in Central European freshwater. Nova Hedwig. Beih 2017, 146, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanata, P.B.; Bijaksana, S.; Dahrin, D.; Nugraha, A.D.; Harlianti, U.; Putra, P.R.A.; Fajar, S.J.; Suandayani, N.K.T.; Pratama, A.; Gumilang, M.F.; et al. Subsurface structure of Bali Island inferred from magnetic and gravity modeling: New insights into volcanic activity and migration of volcanic centers. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2024, 113, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecoraino, G.; D’Alessandro, W.; Inguaggiato, S. The other side of the coin: Geochemistry of alkaline lakes in volcanic areas. In Volcanic Lakes, Advances in Volcanology; Rouwet, D., Christenson, B., Tassi, F., Vandemeulebrouck, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, I. Groundwater Geochemistry and Isotopes; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Septiani, N.K.A.; Suyasa, I.W.B.; Rai, I.N. The Analysis of Water Quality and Pollution Control Strategies in Lake Batur By Implementing Force Field Analysis. Ecotrophic 2022, 16, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney, G.G.; van Lipzig, N.; Thiery, W. Estimating the effect of rainfall on the surface temperature of a tropical lake. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 6357–6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giling, D.P.; Nejstgaard, J.C.; Berger, S.A.; Grossart, H.P.; Kirillin, G.; Penske, A.; Lentz, M.; Sareyka, J.; Gessner, M.O. Thermocline deepening boosts ecosystem metabolism: Evidence from a large-scale lake enclosure experiment simulating a summer storm. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 1448–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, J.L.; Richardson, D.C.; Ewing, H.A.; Hargreaves, B.R.; Samal, N.R.; Vachon, D.; Pierson, D.C.; Lindsey, A.M.; O’Donnell, D.M.; Effler, S.W.; et al. Ecosystem Effects of a Tropical Cyclone on a Network of Lakes in Northeastern North America. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11693–11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, T.; Setiawan, F.; Subehi, L.; Fakhrudin, M.; Triwisesa, E.; Dianto, A.; Matsushita, B. Convection of waters in Lakes Maninjau and Singkarak, tropical oligomictic lakes. Limnology 2022, 23, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, T.; Setiawan, F.; Subehi, L.; Jiang, D.; Matsushita, B. Water temperature and some water quality in Lake Toba, a tropical volcanic lake. Limnology 2023, 24, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Samal, N.R.; Roy, P.K.; Roy, M.B. Electrical Conductivity of Lake Water as Environmental Monitoring—A Case Study of Rudrasagar Lake. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. (IOSR-JESTFT) 2015, 9, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Brocard, G.; Bettini, A.; Pfeifer, H.-R.; Adatte, T.; Morán-Ical, S.; Gonneau, C.; Vásquez, O. Eutrophication and chromium contamination in Lake Chichój, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Span. Rev. Guatem. De Cienc. De La Tierra 2016, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Effendi, H. Telaah Kualitas Air: Bagi Pengelolaan Sumber Daya dan Lingkungan Perairan (Water Quality Review: For the Management of Aquatic Resources and Environment); PT Kanisius: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2003; 258p. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Santoso, A.B.; Hamilton, D.P.; Nomosatryo, S.; Sunaryani, A.; Rustini, H.A.; Rahmadya, A.; Setiawan, F.; Triwisesa, E.; Yulianti, M.; Muttaqien, F.H.; et al. Stratification and mixing dynamics in tropical polymictic Lake Batur, Indonesia. Inland Waters 2025, 15, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | ID | Lat | Long | pH | T | EC | TDS | DO | K+ | NH4+ | Cl− | SO42− | F− | NO3− | NO2− | Loc. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°S) | (°E) | (°C) | (mS) | (ppm) | (mg/L) | (mg/L) | (mg/L) | (mg/L) | (mg/L) | (mg/L) | (mg/L) | (mg/L) | * | |||

| 1 | WB-01 | 8.276 | 115.389 | 9.02 | 22.8 | 2.1 | 1260 | 11.6 | 25.18 | 0 | 204.62 | 511.66 | 12.24 | 29.74 | 0 | a |

| 2 | WB-02 | 8.275 | 115.384 | 8.96 | 23 | 2.1 | 1279 | 11.7 | 29.24 | 8.86 | 234.9 | 610.4 | 6.52 | 0 | 0 | a |

| 3 | WB-04 | 8.270 | 115.401 | 9.16 | 22.8 | 2.09 | 1261 | 11.4 | 26.08 | 2.58 | 211.36 | 491.92 | 4.38 | 0 | 7.38 | a |

| 4 | WB-05 | 8.276 | 115.408 | 9.08 | 23.1 | 2.09 | 1218 | 10.5 | 31.62 | 17.62 | 253.2 | 534.54 | 11.94 | 24.84 | 0 | a |

| 5 | WB-06 | 8.261 | 115.418 | 9.25 | 23.5 | 2.09 | 1255 | 11.5 | 24.84 | 0.7 | 204.4 | 475 | 4.26 | 0 | 0 | a |

| 6 | WB-07 | 8.248 | 115.424 | 9.26 | 23.5 | 2.08 | 1260 | 11.6 | 29.04 | 9.1 | 223.44 | 443.94 | 12.18 | 0 | 0 | a |

| 7 | WB-08 | 8.236 | 115.423 | 9.31 | 24.5 | 2.08 | 1251 | 11.6 | 25.16 | 0.6 | 204.36 | 469.82 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | a |

| 8 | WB-09 | 8.224 | 115.419 | 9.31 | 23.5 | 2.09 | 1247 | 12.8 | 27.66 | 3.14 | 208 | 492.38 | 4.7 | 0 | 0 | a |

| 9 | WB-10 | 8.233 | 115.413 | 9.28 | 23.3 | 2.09 | 1260 | 12.2 | 24.8 | 0.72 | 201.36 | 460.4 | 4.16 | 0 | 0 | a |

| 10 | WB-11 | 8.254 | 115.411 | 9.2 | 22.3 | 2.09 | 1280 | 13.3 | 24.96 | 4.58 | 199.82 | 458.02 | 4.12 | 0 | 0 | a |

| 11 | WB-12 | 8.251 | 115.401 | 9.14 | 23 | 2.09 | 1280 | 11 | 25.72 | 1.44 | 215.24 | 496.78 | 4.54 | 0 | 0 | a |

| 12 | WB-13 | 8.281 | 115.396 | 9.1 | 22.8 | 2.08 | 1290 | 12 | 28.24 | 7.2 | 231.54 | 484.26 | 11.64 | 28.5 | 0 | a |

| 13 | WB-14 | 8.250 | 115.400 | 7.33 | 38.2 | 2.64 | 1730 | (-) | 30.5 | 1.96 | 280.4 | 776.44 | 8.52 | 20.06 | 0 | b |

| 14 | WB-15 | 8.249 | 115.392 | 8.24 | 25 | 1.44 | 872 | (-) | 18.38 | 0.6 | 114.04 | 212.14 | 4.36 | 15.38 | 10.34 | c |

| 15 | WB-16 | 8.252 | 115.400 | 7.49 | 35.6 | 2.17 | 1450 | (-) | 23.54 | 1.18 | 206.6 | 414.28 | 4.32 | 25.53 | 5.91 | b |

| 16 | WB-17 | 8.221 | 115.418 | 7.14 | 22.6 | 0.66 | 382 | (-) | 23.98 | 1.46 | 55.62 | 72.6 | 11.04 | 88.2 | 21.78 | c |

| 17 | WB-18 | 8.221 | 115.418 | 6.98 | 22.5 | 1.15 | 693 | (-) | 19.32 | 0.98 | 88.98 | 201.84 | 3.92 | 141.36 | 7.36 | c |

| 18 | WB-19 | 8.281 | 115.388 | 8.66 | 17.6 | 2.02 | 1188 | (-) | 26.68 | 1.38 | 213.66 | 415.38 | 11.52 | 29.82 | 0 | c |

| min | 6.98 | 17.60 | 0.66 | 382.00 | 10.50 | 18.38 | 0.00 | 55.62 | 72.60 | 3.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| max | 9.31 | 38.20 | 2.64 | 1730.00 | 13.30 | 31.62 | 17.62 | 280.40 | 776.44 | 12.24 | 141.36 | 21.78 | ||||

| avg | 8.66 | 24.42 | 1.95 | 1192.00 | 11.77 | 25.83 | 3.56 | 197.31 | 445.66 | 7.14 | 22.41 | 2.93 | ||||

| LOD | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.98 | 0.67 | |||||||||

| Parameter | [12] | [13] | This Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 2011 | July 2011 | October 2011 | June 2018 | June 2023 | November 2023 | |

| T (°C) | 24.1–26.4 | 22.9–24.1 | 24.2–26.2 | 23.2–23.6 | 22.3–24.5 | 24.9–26.9 |

| pH water (unit) | 8.81–9.50 | 8.21–8.69 | 8.62–9.00 | 8.1–8.9 | 8.96–9.31 | 9.13–9.30 |

| DO (mg/L) | 3.22–6.82 | 0.62–5.56 | 4.92–8.25 | 7.07–7.9 | 10.5–13.3 | |

| TDS (ppm) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 1340–1860 | 1218–1290 | 1340–1360 |

| EC (mS) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 2.08–2.10 | 2.15–2.17 |

| NO2− (mg/L) | 0.01–0.04 | 0.06–0.14 | 0.00–0.13 | (-) | 0–7.38 | (-) |

| NO3− (mg/L) | 0.07–0.53 | 0.28–0.65 | 0.05–1.56 | (-) | 0–29.74 | (-) |

| NH4+ (mg/L) | 0.56–1.31 | 0.12–0.55 | 0.23–1.06 | (-) | 0–17.62 | (-) |

| TP (mg/L) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 0.404–0.739 | (-) | (-) |

| Chlorophyll-a (mg/m3) | 3.06–12.28 | 4.48–21.38 | 1.70–7.75 | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| Parameters | This Study * | [33] | [34] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean | Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | |||

| NH4+ (mg/L) | June | 0 | 17.62 | 4.71 | (-) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | (-) |

| Cl− (mg/L) | 199.82 | 253.2 | 216.02 | 250 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 600 | |

| SO42− (mg/L) | 443.94 | 610.40 | 494.09 | 250 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 400 | |

| F− (mg/L) | 4.12 | 12.24 | 7.07 | 2.19 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | (-) | |

| NO3− (mg/L) | 0 | 29.74 | 6.92 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 20 | |

| NO2− (mg/L) | 0 | 7.38 | 0.62 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | (-) | |

| pH | June | 8.96 | 9.31 | 9.17 | 6.5–8.5 | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| November | 9.13 | 9.3 | 9.2 | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||

| EC μS/cm | June | 2080 | 2100 | 2090 | 400 | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| November | 2150 | 2170 | 2160 | ||||||

| TDS (ppm) | June | 1218 | 1290 | 1262 | 300–900 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 2000 |

| November | 1340 | 1360 | 1346 | ||||||

| DO (mg/L) | November | 10.5 | 13.3 | 11.8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| pH | T | EC | TDS | K+ | NH4+ | Cl− | SO42− | F− | NO3− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | 0.179 | |||||||||

| EC | 0.097 | 0.381 | ||||||||

| TDS | 0.120 | 0.246 | 0.733 | |||||||

| K+ | 0.209 | 0.038 | 0.365 | 0.339 | ||||||

| NH4+ | 0.087 | −0.163 | 0.106 | 0.263 | 0.715 | |||||

| Cl− | 0.063 | 0.205 | 0.498 | 0.526 | 0.911 | 0.615 | ||||

| SO42− | 0.247 | 0.199 | 0.711 | 0.493 | 0.754 | 0.315 | 0.740 | |||

| F− | −0.133 | −0.076 | 0.072 | 0.025 | 0.653 | 0.394 | 0.602 | 0.366 | ||

| NO3− | −0.791 | −0.362 | −0.325 | −0.331 | −0.200 | −0.172 | −0.155 | −0.354 | 0.299 | |

| NO2− | −0.553 | −0.070 | −0.412 | −0.376 | −0.620 | −0.229 | −0.545 | −0.613 | −0.242 | 0.389 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Harlianti, U.; Fajar, S.J.; Bijaksana, S.; Iskandar, I.; Lubis, R.F.; Papa, R.D.S.; Suryanata, P.B.; Suandayani, N.K.T. Physicochemical Properties and Diatom Diversity in the Sediments of Lake Batur: Insights from a Volcanic Alkaline Ecosystem. Earth 2026, 7, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth7010005

Harlianti U, Fajar SJ, Bijaksana S, Iskandar I, Lubis RF, Papa RDS, Suryanata PB, Suandayani NKT. Physicochemical Properties and Diatom Diversity in the Sediments of Lake Batur: Insights from a Volcanic Alkaline Ecosystem. Earth. 2026; 7(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth7010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarlianti, Ulvienin, Silvia Jannatul Fajar, Satria Bijaksana, Irwan Iskandar, Rachmat Fajar Lubis, Rey Donne S. Papa, Putu Billy Suryanata, and Ni Komang Tri Suandayani. 2026. "Physicochemical Properties and Diatom Diversity in the Sediments of Lake Batur: Insights from a Volcanic Alkaline Ecosystem" Earth 7, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth7010005

APA StyleHarlianti, U., Fajar, S. J., Bijaksana, S., Iskandar, I., Lubis, R. F., Papa, R. D. S., Suryanata, P. B., & Suandayani, N. K. T. (2026). Physicochemical Properties and Diatom Diversity in the Sediments of Lake Batur: Insights from a Volcanic Alkaline Ecosystem. Earth, 7(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth7010005