Morphology and Sedimentology of La Maruca/Pinquel Cobble Embayed Beach: Evolution from 1984 to 2024 (Santander, NW Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Identification and mapping of the various morphologies present on the beach, along with their spatial and temporal distributions, using high-quality orthophotos;

- -

- Characterization of the granulometric and particle shape parameters across the entire fieldwork;

- -

- Correlation between the granulometric characteristics and the coastal dynamic processes influencing the area;

- -

- Proposal of a projection of the beach’s future evolution based on observed trends over the past 40 years, which can be used as a model for managing beaches in other coastal areas.

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Acquisition of Historical Orthophotographs and Geomorphological Mapping

3.2. Field Campaign

3.3. Characterization of Granulometric Parameters

3.4. Shape of Particles

3.5. Analysis of Coastal Dynamic Agents

3.5.1. Waves

3.5.2. Tides

3.5.3. Sea Level

4. Results

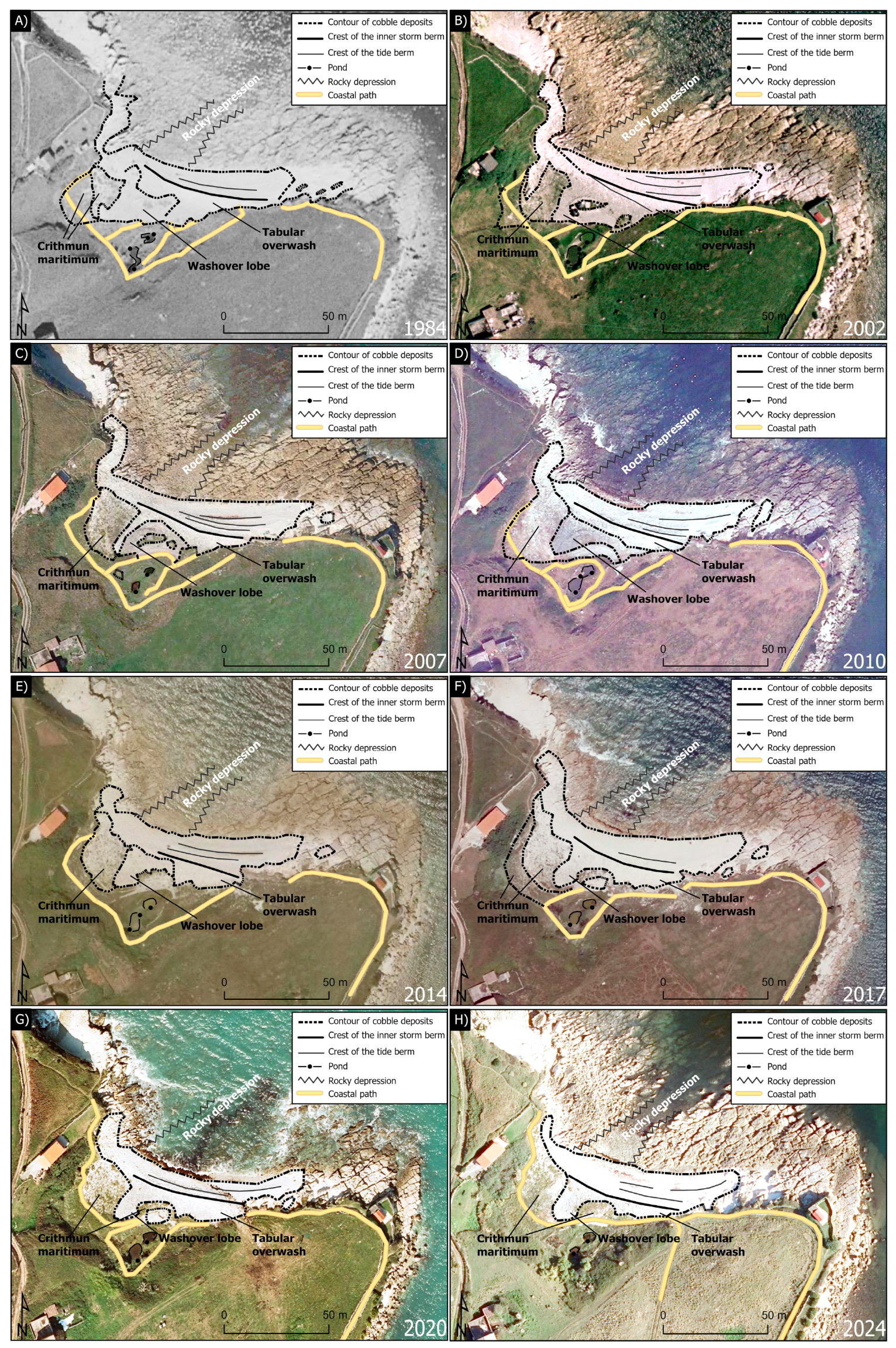

4.1. Geomorphological Mapping on the Basis of Historical Orthophotographs and Fieldwork

4.2. Granulometric Parameters, Shape Characterization, and Coastal Dynamic Agents

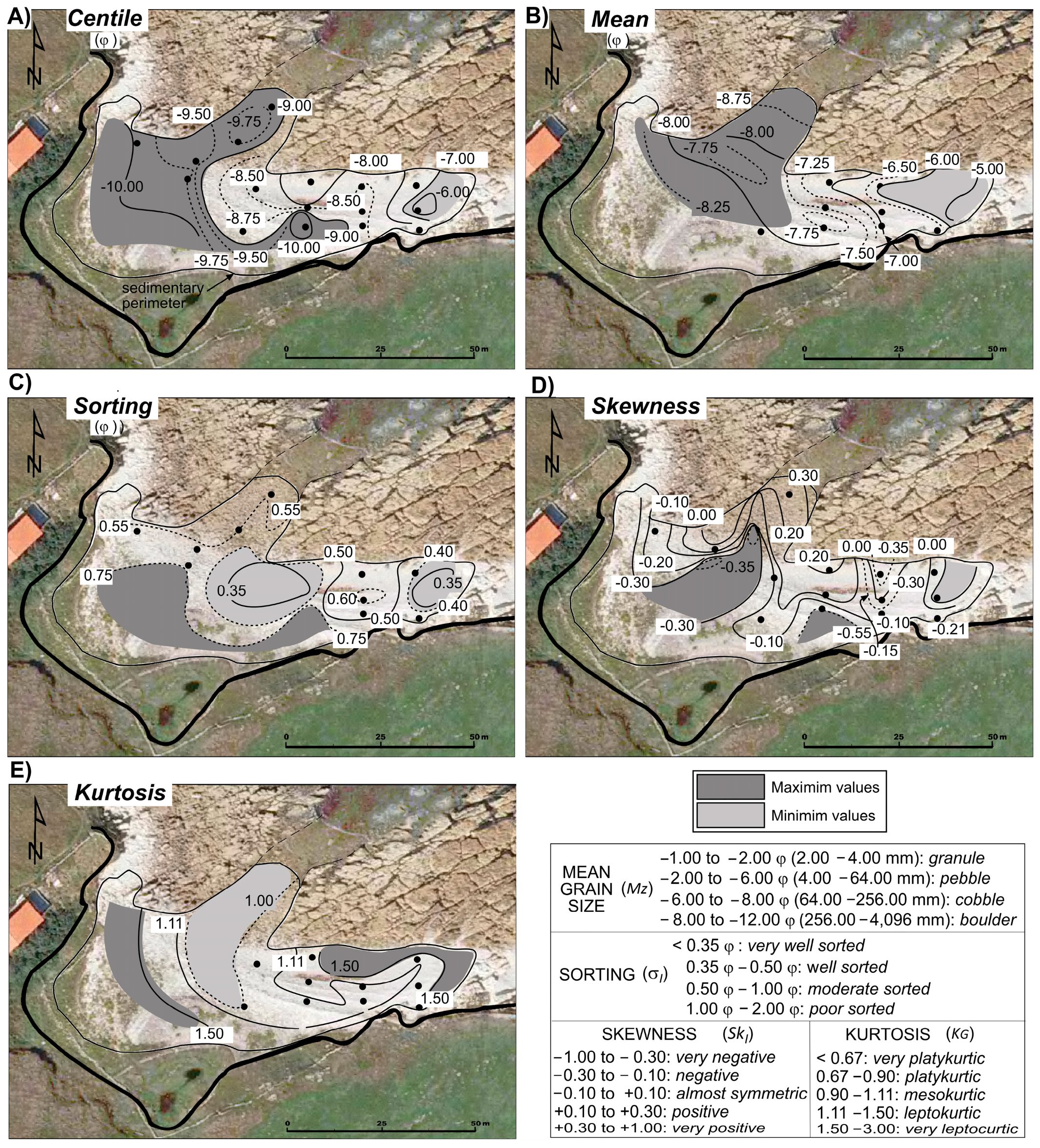

4.2.1. Granulometries

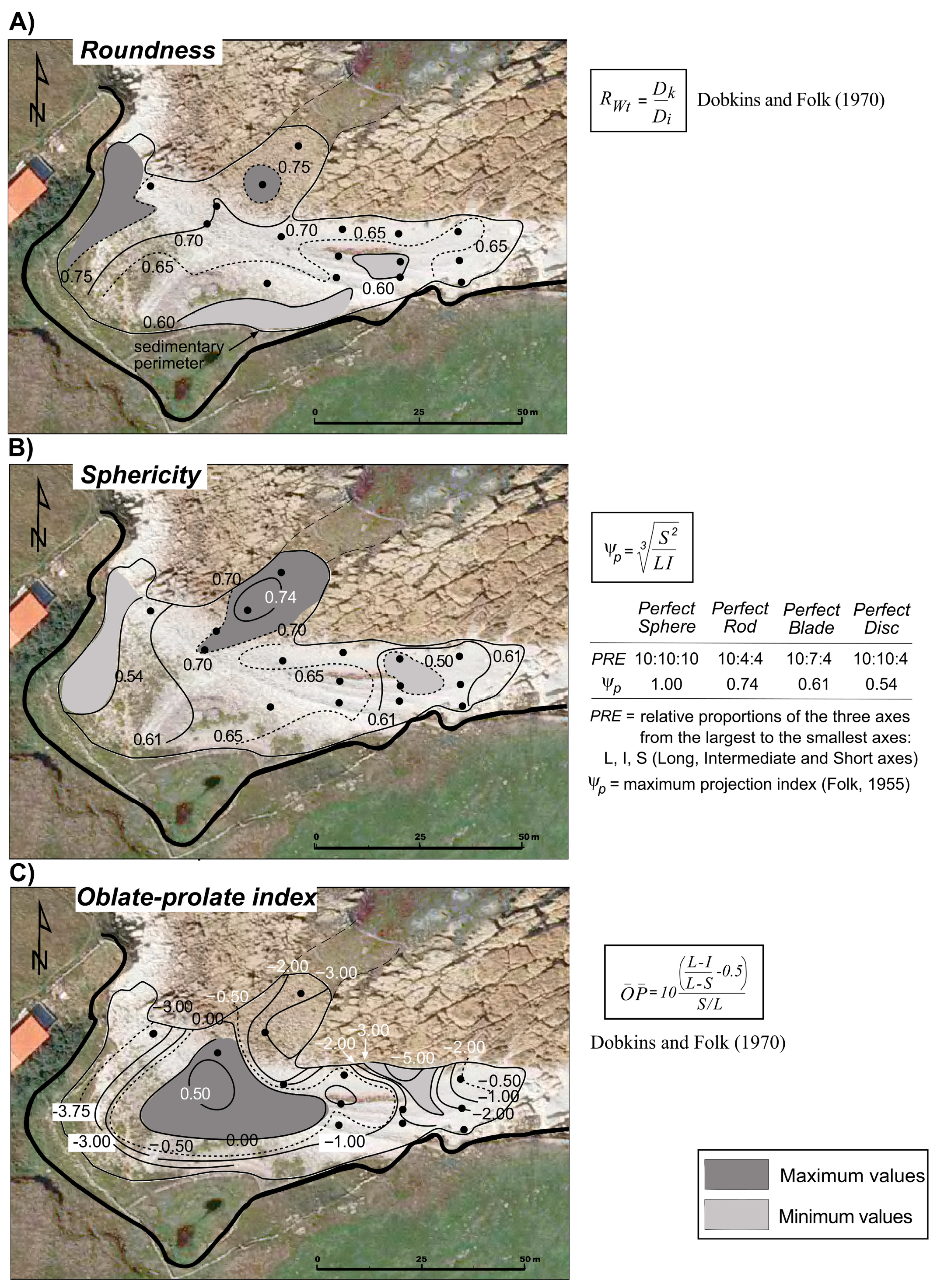

4.2.2. Particle Shape

4.3. Morphosedimentary Beach Evolution from 1984 to 2024

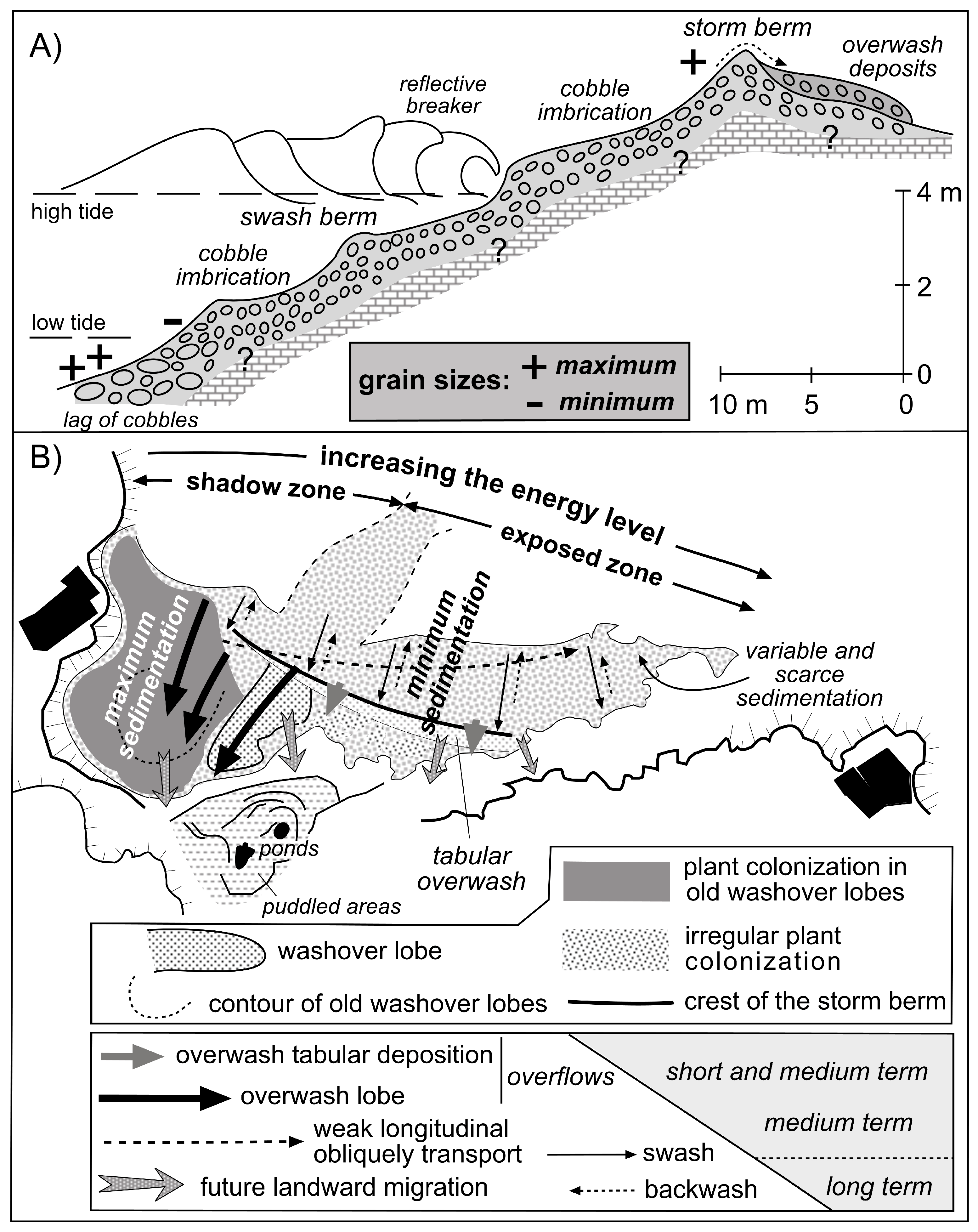

5. Discussion

5.1. Sedimentary Source Areas

5.2. Morphosedimentary Distribution 1984–2024

5.3. Morphosedimentary and Dynamic Model

6. Future Evolution Model

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, R.; Martínez, M.L.; Van Tussenbroek, B.I.; Guzmán-Rodríguez, L.O.; Mendoza, E.; López-Portillo, J. A Framework to Manage Coastal Squeeze. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usai, A.; Simeone, S.; Trogu, D.; Porta, M.; De Muro, S. A Morphometric Analysis of Embayed Beaches: Southern Sardinia Island. Geomorphology 2025, 483, 109838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalezios, N.R.; Eslamian, S.; Ostad-Ali-Askari, K.; Rabbani, S.; Saeidi-Rizi, A. Sediments. In Encyclopedia of Engineering Geology; Bobrowsky, P.T., Marker, B., Eds.; Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 818–819. ISBN 978-3-319-73566-5. [Google Scholar]

- Folk, R.L.; Ward, W.C. Brazos River Bar [Texas]; a Study in the Significance of Grain Size Parameters. J. Sediment. Res. 1957, 27, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujan, N.; Cox, R.; Masselink, G. From Fine Sand to Boulders: Examining the Relationship between Beach-Face Slope and Sediment Size. Mar. Geol. 2019, 417, 106012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.J. The Shape of Rock Particles, a Critical Review. Sedimentology 1980, 27, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grottoli, E.; Bertoni, D.; Ciavola, P. Short-and Medium-Term Response to Storms on Three Mediterranean Coarse-Grained Beaches. Geomorphology 2017, 295, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.D.; Short, A.D. Morphodynamic Variability of Surf Zones and Beaches: A Synthesis. Mar. Geol. 1984, 56, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masselink, G.; Short, A.D. The Effect of Tide Range on Beach Morphodynamics and Morphology: A Conceptual Beach Model. J.Coast. Res. 1993, 9, 785–800. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4298129 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Buscombe, D.; Masselink, G. Concepts in Gravel Beach Dynamics. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2006, 79, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, S.; Paris, R. Boulder Accumulations Related to Storms on the South Coast of the Reykjanes Peninsula (Iceland). Geomorphology 2010, 114, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Levoy, F.; Monfort, O.; Curoy, J.; De Saint Léger, E.; Delahaye, D. Impact of Sand Content and Cross-Shore Transport on the Morphodynamics of Macrotidalgravel Beaches (Haute-Normandie, English Channel). Z. Geomorphol. 2008, 52, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorang, M.S. Predicting Threshold Entrainment Mass for a Boulder Beach. J. Coast. Res. 2000, 16, 432–445. [Google Scholar]

- Soloy, A.; Lopez Solano, C.; Turki, E.I.; Mendoza, E.T.; Lecoq, N. Rapid Changes in Permeability: Numerical Investigation into Storm-Driven Pebble Beach Morphodynamics with XBeach-G. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.; Hanslow, D.J. Wave Runup Distributions on Natural Beaches. J. Coast. Res. 1991, 7, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Bujak, D.; Ilic, S.; Miličević, H.; Carević, D. Wave Runup Prediction and Alongshore Variability on a Pocket Gravel Beach under Fetch-Limited Wave Conditions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidoro, A. The Effect of Grain Size Distribution and Bimodal Sea States on Coarse Beach Sediment Dynamics. Ph.D. Thesis, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martos de la Torre, E. Evolución Morfosedimentaria de La Playa de Cantos de Aramar. Master’s Thesis, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bluck, B.J. Sedimentation of Beach Gravels; Examples from South Wales. J. Sediment. Res. 1967, 37, 128–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellowes, T.E.; Vila-Concejo, A.; Gallop, S.L. Morphometric Classification of Swell-Dominated Embayed Beaches. Mar. Geol. 2019, 411, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.A.; Lee, C.T. Discrimination between Coastal Subenvironments using Textural Characteristics. Sedimentology 1994, 41, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, M.A.; Griggs, G.B.; Edil, T.B.; Guy, D.E.; Kelley, J.T.; Komar, P.D.; Mickelston, D.M.; Shipman, H.M. Formation, Evolution, and Stability of Coastal Cliffs–Status and Trends. In U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1693; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1984; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bonachea, J.; Remondo, J.; Rivas, V. Estuaries in Northern Spain: An Analysis of Their Sedimentation Rates. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnolas, A.; Pujalte, V. La Cordillera Pirenaica: Definición, Límites y División. In Geología de España; Vera, J.A., Ed.; IGME: Madrid, Spain, 2004; pp. 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez del Pozo, J.; Portero García, J.M. Mapa Geológico de España, Escala 1:50,000. Hoja Geológica de Santander 35; IGME: Madrid, Spain, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- García-Herrera, G. Estudio Geológico-Geotécnico del Subsuelo Urbano de la Ciudad de Santander. Master’s Thesis, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Google Earth. Available online: https://earth.google.com (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Mapas Cantabria. Visualizador de Mapas del Gobierno de Cantabria. Available online: https://mapas.cantabria.es (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Centro de Descargas Del CNIG (IGN). Available online: https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/ortofoto-pnoa-maxima-actualidad (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Plan Nacional de Ortofotografía Aérea. Available online: https://pnoa.ign.es/web/portal/pnoa-imagen/ortofotos-pnoa-anuales (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Tutiempo Network, S.L. Tabla de Mareas en Santander marzo de 2023 (Cantabria). Available online: https://www.tutiempo.net/mareas/espana/santander/marzo-2023.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Emery, K.O. A Simple Method of Measuring Beach Profiles. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1961, 6, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, I.; Lloyd, G. A Simple Low-Cost Method for One Person Beach Profiling. J. Coast. Res. 2004, 204, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Hossain, M.S.; Sharifuzzaman, S.M. A Simple and Inexpensive Method for Muddy Shore Profiling. Chin. J. Ocean. Limnol. 2014, 32, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodger, S.; Russell, P.; Davidson, M. Grain-Size Distributions on High-Energy Sandy Beaches and their Relation to Wave Dissipation. Sedimentology 2017, 64, 1289–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orford, J.D. Discrimination of Particle Zonation on a Pebble Beach. Sedimentology 1975, 22, 441–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Switzer, A.D. 14.19 Measuring and Analyzing Particle Size in a Geomorphic Context. In Treatise on Geomorphology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 224–242. ISBN 978-0-08-088522-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dobkins, J.E.; Folk, R.L. Shape Development on Tahiti-Nui. J. Sediment. Res. 1970, 40, 1167–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blott, S.J.; Pye, K. Gradistat: A Grain Size Distribution and Statistics Package for the Analysis of Unconsolidated Sediments. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2001, 26, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, G.; Martínez Cedrún, P. Saucer Blowouts in the Coast Dune Fields of NW Spain. J. Iber. Geol. 2024, 50, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakey, R.J.; Green, M.; Carling, P.A.; Lee, M.W.E.; Sear, D.A.; Warburton, J. Grain-Shape Analysis-A New Method for Determining Representative Particle Shapes for Populations of Natural Grains. J. Sediment. Res. 2005, 75, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, R.L. Student Operator Error in Determination of Roundness, Sphericity, and Grain Size. J. Sediment. Res. 1955, 25, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karditsa, A.; Poulos, S.E. The Application of Grain Size Trend Analysis in the Fine Grained Seabed Sediment of Alexandroupolis Gulf. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2016, 47, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Poizot, E.; Méar, Y.; Biscara, L. Sediment Trend Analysis through the Variation of Granulometric Parameters: A Review of Theories and Applications. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2008, 86, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, M.E.; Kench, P.S.; Kantor, M.S. Longshore Transport of Cobbles on a Mixed Sand and Gravel Beach, Southern Hawke Bay, New Zealand. Mar. Geol. 2011, 287, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orford, J.D.; Carter, R.W.G.; Forbes, D.L. Gravel Barrier Migration and Sea Level Rise: Some Observations from Story Head, Nova Scotia, Canada. J. Coast. Res. 1991, 7, 477–489. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4297854 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Erikson, L.H.; O’Neill, A.C.; Barnard, P.L.; Vitousek, S.; Limber, P.W. Climate Change-Driven Cliff and Beach Evolution at Decadal to Centennial Time Scales. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Coastal Dynamics 2017, Helsingør, Denmark, 12–16 June 2017; pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Puertos del Estado: PORTUS. Available online: https://portus.puertos.es (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Rueda, A.; Costales, A.; Bruschi, V.; Sánchez-Espeso, J.; Méndez, F. Regional Coastal Cliff Classification: Application to the Cantabrian Coast, Spain. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2024, 308, 108900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasicchio, G.R.; Archetti, R.; D’Alessandro, F.; Sloth, P. Long Shore Transport at Berm Breakwaters and Gravel Beaches. In Coastal Structures 2007, Proceedings of the 5th Coastal Structures International Conference, CSt07, Venice, Italy, 2–4 July 2007; World Scientific Publishing Company: Venice, Italy, 2009; pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Flor, G.; Flor-Blanco, G. Aspectos Morfológicos, Dinámicos y Sedimentarios del Sector Costero: Desembocadura del Nalón-Playa de Bañugues: Problemática Ambiental. In Guía de Campo; University of Oviedo: Oviedo, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dashtgard, S.E.; MacEachern, J.A.; Frey, S.E.; Gingras, M.K. Tidal Effects on the Shoreface: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Sediment. Geol. 2012, 279, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, A.D.; Masselink, G. Embayed and Structurally Controlled Beaches. In Handbook of Beach and Shoreface Morphodynamics; Short, A.D., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 230–250. ISBN 978-0-471-96570-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chust, G.; González, M.; Fontán, A.; Revilla, M.; Alvarez, P.; Santos, M.; Cotano, U.; Chifflet, M.; Borja, A.; Muxika, I.; et al. Climate Regime Shifts and Biodiversity Redistribution in the Bay of Biscay. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 803, 149622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, R.; Méndez, F.J. Inundación Costera Originada por la Dinámica Marina. Ingeniería y Territorio 2006, 74, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Losada, I.; Izaguirre, C.; Diaz, P. Cambio Climático En La Costa Española; Oficina Española de Cambio Climático, Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2014; p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos, S.; González, A.; Díaz de Terán, J.R. Geología y Geomorfología de La Península de La Magdalena. In Estudio del Medio Físico. Plan Director de la Península de la Magdalena; Sáinz Vidal, E., Ed.; Ayuntamiento de Santander: Santander, UK, 2008; pp. 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, M.; Donnelly, C.; Jiménez, J.A.; Hanson, H. Analytical Model of Beach Erosion and Overwash during Storms. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Marit. Eng. 2009, 162, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.O.; Michel, J.; Betenbaugh, D.V. The Intermittently Exposed, Coarse-Grained Gravel Beaches of Prince William Sound, Alaska: Comparison with Open-Ocean Gravel Beaches. J. Coast. Res. 2010, 2010, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masselink, G.; Li, L. The Role of Swash Infiltration in Determining the Beachface Gradient: A Numerical Study. Mar. Geol. 2001, 176, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, F.M.; Hughes, M.G.; Baldock, T.E. Beach Face and Berm Morphodynamics Fronting a Coastal Lagoon. Geomorphology 2006, 82, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poate, T.; Masselink, G.; Davidson, M.; McCall, R.; Russell, P.; Turner, I. High Frequency In-Situ Field Measurements of Morphological Response on a Fine Gravel Beach during Energetic Wave Conditions. Mar. Geol. 2013, 342, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komar, P.D. Beach Processes and Sedimentation, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Lebanon, IN, USA, 1998; Volume 1, ISBN 978-0-13-754938-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, E. Behavior of Grain Size Characteristics on Reflective and Dissipative Foreshores, Broken Bay, Australia. J. Sediment. Res. 1982, 52, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, E.J. Chapter Six Gravel Beaches and Barriers. Dev. Mar. Geol. 2008, 4, 289–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, R.M. Mixed Sand and Gravel Beaches: Morphology, Processes and Sediments. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 1980, 4, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.M.; Wang, P.; Puleo, J.A. Storm-Driven Cyclic Beach Morphodynamics of a Mixed Sand and Gravel Beach along the Mid-Atlantic Coast, USA. Mar. Geol. 2013, 346, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, C.; Ferreira, Ó. Mechanisms and Timescales of Beach Rotation. In Sandy Beach Morphodynamics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; You, Z.J.; Liang, B. Laboratory Investigation of Coastal Beach Erosion Processes under Storm Waves of Slowly Varying Height. Mar. Geol. 2020, 430, 106321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascom, W.N. The Relationship between Sand Size and Beach-Face Slope. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1951, 32, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFall, B.C. The Relationship between Beach Grain Size and Intertidal Beach Face Slope. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 35, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, R.F.; Kirk, R.M. Relationships between Grain Size, Size-Sorting, and Foreshore Slope on Mixed Sand-Shingle Beaches. N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys. 1969, 12, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Sánchez, M.; Fachin, S.; Sancho, F.; Losada, M.A. Relation between Beachface Morphology and Wave Climate at Trafalgar Beach (Cádiz, Spain). Geomorphology 2008, 99, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelle, B.; Marieu, V.; Bujan, S.; Splinter, K.D.; Robinet, A.; Sénéchal, N.; Ferreira, S. Impact of the Winter 2013–2014 Series of Severe Western Europe Storms on a Double-Barred Sandy Coast: Beach and Dune Erosion and Megacusp Embayments. Geomorphology 2015, 238, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masselink, G.; Castelle, B.; Scott, T.; Dodet, G.; Suanez, S.; Jackson, D.; Floc’h, F. Extreme Wave Activity during 2013/2014 Winter and Morphological Impacts along the Atlantic Coast of Europe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 2135–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, G.; Flor-Blanco, G.; Flores, C. Cambios Ambientales por los Temporales de Invierno de 2014 en la Costa Asturiana (NO de España). Trab. De Geol. 2014, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manero-Lecea, G. Análisis de los Temporales Marinos entre 2013–2014 y de sus Impactos en las Costas de Cantabria. Master’s Thesis, University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Garrote, J.; Díaz-Álvarez, A.; Nganhane, H.V.; Heydt, G.G. The Severe 2013–14 Winter Storms in the Historical Evolution of Cantabrian (Northern Spain) Beach-Dune Systems. Geosciences 2018, 8, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, M.J.; Buscombe, D. Morphological Change and Sediment Dynamics of the Beach Step on a Macrotidal Gravel Beach. Mar. Geol. 2008, 249, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R.; Shulmeister, J. A Field Based Classification Scheme for Gravel Beaches. Mar. Geol. 2002, 186, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettijohn, F.J.; Potter, P.E.; Siever, R. Sand and Sandstone; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1973; ISBN 978-0-387-90071-1. [Google Scholar]

- Angelidakis, V.; Nadimi, S.; Utili, S. Elongation, Flatness and Compactness Indices to Characterise Particle Form. Powder Technol. 2022, 396, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, B.J.A.; de Schipper, M.A.; Ruessink, B.G. Sediment Sorting at the Sand Motor at Storm and Annual Time Scales. Mar. Geol. 2016, 381, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, D.L. Sorting of Sediments in the Light of Fluid Mechanics. J. Sediment. Res. 1949, 19, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, R.L. A Review of Grain-Size Parameters. Sedimentology 1966, 6, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, P. An Interpretation of Trends in Grain-Size Measures. J. Sediment. Res. 1981, 51, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, P.; Bowles, D. The Effects of Sediment Transport on Grain-Size Distributions. J. Sediment. Res. 1985, 55, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshak, S. Earth: Portrait of a Planet/Stephen Marshak; W. W. Norton and Company: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-393-64031-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, D.J. Reflective Beaches. In Encyclopedia of Coastal Science; Schwartz, M.L., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 795–797. ISBN 978-1-4020-3880-8. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, R.W. Coastal Environments; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Elsevier: London, UK, 1988; ISBN 978-0-08-050214-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, L.H. Gravel Imbrication on the Deflating Backshores of Beaches on Prince Edward Island, Canada. Sediment. Geol. 1996, 101, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.W.G.; Orford, J.D. The Morphodynamics of Coarse Clastic Beaches and Barriers: A Short- and Long-Term Perspective. J. Coast. Res. 1993, 158–179. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25735728 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Menéndez-García, M.; Pérez-García, J.; Méndez-Incera, F.J.; Izaguirre-Lasa, C. Arcimis: Cambios en los Eventos Extremos de Inundación en la Costa. In Publicaciones de la Asociación Española de Climatología. Serie A; Asociación Española de Climatología: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Losada, I.; Toimil-Silva, A.; Díaz-Simal, P. Asistencia Técnica a La Elaboración de Un Estudio Sobre La Adaptación al Cambio Climático de La Costa Del Principado de Asturias. Actividad 3: Estrategia de Adaptación; Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2015; pp. 1–312. [Google Scholar]

- De Sanjosé Blasco, J.J.; Gómez-Lende, M.; Sánchez-Fernández, M.; Serrano-Cañadas, E. Monitoring Retreat of Coastal Sandy Systems Using Geomatics Techniques: Somo Beach (Cantabrian Coast, Spain, 1875–2017). Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, G.; Flor-Blanco, G.; Martínez-Cedrún, P.; Flores-Soriano, C.; Borghero, C. Aeolian Dune Fields in the Coasts of Asturias and Cantabria (Spain, NW Iberian Peninsula). In The Spanish Coastal Systems: Dynamic Processes, Sediments and Management; Morales, J.A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 585–609. ISBN 978-3-319-93169-2. [Google Scholar]

- De Sanjosé Blasco, J.J.; Serrano-Cañadas, E.; Sánchez-Fernández, M.; Gómez-Lende, M.; Redweik, P. Application of Multiple Geomatic Techniques for Coastline Retreat Analysis: The Case of Gerra Beach (Cantabrian Coast, Spain). Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Codrón, J.C.; Rasilla-Álvarez, D.F. Coastline Retreat, Sea Level Variability and Atmospheric Circulation in Cantabria (Northern Spain). J. Coast. Res. 2006, 49–54. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25737381 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Bruun, P. Sea-Level Rise as a Cause of Shore Erosion. J. Waterw. Harb. Div. 1962, 88, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.G. Additional Sediment Transport Input to Nearshore Region. Shore Beach 1987, 55, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel, D.L.; Dean, R.G. Convolution Method for Time-Dependent Beach-Profile Response. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean. Eng. 1993, 119, 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson-Arnott, R.G.D. Conceptual Model of the Effects of Sea Level Rise on Sandy Coasts. J. Coast. Res. 2005, 21, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborda, R.; Ribeiro, M.A. A Simple Model to Estimate the Impact of Sea-Level Rise on Platform Beaches. Geomorphology 2015, 234, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño, J.; Coco, G.; Cagigal, L.; Mendez, F.; Rueda, A.; Bryan, K.R.; Harley, M.D. A Multiscale Approach to Shoreline Prediction. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL090587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.A.G.; Pilkey, O.H. Sea-Level Rise and Shoreline Retreat: Time to Abandon the Bruun Rule. Glob. Planet. Change 2004, 43, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor-Blanco, G.; Flor, G.; Pando, L. Evolution of the Salinas-El Espartal and Xagó Beach/Dune Systems in North-Western Spain over Recent Decades: Evidence for Responses to Natural Processes and Anthropogenic Interventions. Geo-Mar. Lett. 2013, 33, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasilla, D.; García-Codron, J.C.; Garmendia, C.; Herrera, S.; Rivas, V. Extreme Wave Storms and Atmospheric Variability at the Spanish Coast of the Bay of Biscay. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Flight Date | Resolution (cm) | GSD: Ground Sample Distance (cm) | RMSE: Root Mean Square Error (cm) | Source of the Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14–15 September 2024 | 25 | 25 | 50 | [28,29] |

| 7 August 2023 | 15 | 15 | 30 | [28,29] |

| 29 September 2020 | 15 | 15 | 30 | [28,29] |

| 3 July 2017 | 25 | No Data | No Data | [28,29] |

| 27 July 2014 | 25 | 25 | 50 | [28,29] |

| 5 September 2010 | 25 | 50 | 100 | [28,29] |

| 5 September 2007 | 25 | 10 | 20 | [28,29] |

| 10 September 2002 | 25 | 50 | 50 | [28,29] |

| November 1984 | 25 | 50 | 100 | [29] |

| Sample | Centile | Mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ϕ | mm | ϕ | mm | |

| a | −9.79 | 890 | −8.90 | 480 |

| b | −10.30 | 1340 | −9.43 | 690 |

| c | −9.57 | 760 | −8.87 | 470 |

| d | −8.68 | 410 | −7.59 | 192 |

| e | −8.49 | 361 | −7.05 | 132 |

| Year | Surface Containing Deposits (m2) | Number of Crests (berms) | Crest Length (m) | Distance Between Crests (m) | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 2910.3 | 2 | 37.5–61.8 | 4.2 | SW fixed vegetation |

| 2002 | 3058.3 | 4 | 49.4–36.2–25.9–54.3 | 3.7–4.1–3.1 | Overwash in the backbeach |

| 2007 | 2795.2 | 4 | 29.5–41.9–31.3–53.1 | 2.8–2.5–3.4 | Fixed backbeach |

| 2010 | 3032.5 | 4 | 34.1–29.2–20.8–55.2 | 4.5–2.8–2.3 | Well-developed berms |

| 2014 | 2437.4 | 3 | 40.5–34.0–39.9 | 3.1–4.3 | New lobe |

| 2017 | 3114.3 | 2 | 27.6–50.9 | 4.6 | Active overwash sheet and lobe |

| 2020 | 2177.0 | 3 | 33.3–39.4–54.3 | 2.4–2.8 | Upper crest erosion |

| 2023 | 2314.7 | 3 | 52.3–47.5–48.4 | 5.07–2.8 | Lobe is inactive |

| 2024 | 2449.5 | 3 | 42.9–30.5–55.2 | 4.4–4.2 | Lobe is fixing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonachea, J.; Flor, G. Morphology and Sedimentology of La Maruca/Pinquel Cobble Embayed Beach: Evolution from 1984 to 2024 (Santander, NW Spain). Earth 2025, 6, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040159

Bonachea J, Flor G. Morphology and Sedimentology of La Maruca/Pinquel Cobble Embayed Beach: Evolution from 1984 to 2024 (Santander, NW Spain). Earth. 2025; 6(4):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040159

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonachea, Jaime, and Germán Flor. 2025. "Morphology and Sedimentology of La Maruca/Pinquel Cobble Embayed Beach: Evolution from 1984 to 2024 (Santander, NW Spain)" Earth 6, no. 4: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040159

APA StyleBonachea, J., & Flor, G. (2025). Morphology and Sedimentology of La Maruca/Pinquel Cobble Embayed Beach: Evolution from 1984 to 2024 (Santander, NW Spain). Earth, 6(4), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040159