1. Introduction

Secondary geological formations are the predominant geothermal reservoirs in Northern Algeria, feeding over 282 thermal springs primarily located in the country’s northeastern and northwestern regions. These springs emerge from various aquifer systems, some of which are regional while others are local. With emergence temperatures ranging from 27 to 97 °C [

1], consistently higher than the ambient air, these thermal springs are frequently utilized in spas, holding significant therapeutic and economic value.

Situated within the Constantine highlands of northeastern Algeria, Teleghma is uniquely positioned near the prominent thermal spring systems of Grouz and Constantine, suggesting its potential as a geothermal hotspot. The region exhibits a geothermal gradient varying between 27 °C and 42 °C/km, according to the geothermal gradient map of Northern Algeria [

2].

Despite this potential, Teleghma was not historically identified as a geothermal zone in previous well-known studies on the thermal waters of the Algerian northeast, particularly those concerning the Constantinois system [

3,

4,

5,

6]. This omission is attributed to the relatively recent emergence of thermal springs in the Teleghma region, a phenomenon that coincided with the construction of the Grouz Dam and the subsequent drying up of some hot springs at the base of Djebel Grouz [

7]. Furthermore, several boreholes were drilled in the Teleghma region, extending from the base of Djebel Toukouia to the northwest across the Mio-Plio-Quaternary plain. These boreholes, which are over 120 m deep, have an emergence temperature of 42 °C to 50 °C and flow rates of 10 Liters per second. They have since been converted into thermal baths, known as Hammam Safsaf, Hammam Chaouch, and Hammam Ouled Djali.

Geothermal waters undergo significant chemical changes as they rise from deep reservoirs to the surface. This creates new chemical balances in shallower layers, forming distinct reservoirs [

8].

The chemical composition of geothermal water is primarily determined by its interaction with the surrounding rock. This includes major and trace elements, as well as their isotopes [

9]. To understand these geochemical processes, we used chemical and mathematical methods. Specifically, we performed mineral saturation index calculations and inverse chemical modeling using PHREEQC Interactive software (version 3) [

10]. This is a well-established method in hydrogeochemical research, and its effectiveness in identifying element origins and reaction mechanisms has been confirmed by numerous studies on carbonate reservoirs [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14].

This type of modeling requires a detailed understanding of the chemical composition of the rock formations and the relevant reaction chemistry. As a first step, we focused on major ions, pH, and temperature at the point of emergence to calculate the saturation index. This allowed us to identify the key mineral phases that were either dissolving or precipitating. The hydrodynamic behavior of the Teleghma system is controlled by the regional fault network, which promotes deep circulation and upward migration of thermal fluids. Recharge likely occurs through the fractured Eocene limestones at higher elevations, where meteoric water infiltrates and percolates downward, acquiring heat and solutes through prolonged water–rock interactions. As these fluids ascend along NE–SW and NW–SE fault zones, their chemistry evolves through dissolution of evaporitic minerals (halite, gypsum) and cation exchange between Na+ and Ca2+, linking the hydrodynamic regime directly to groundwater quality.

Similar hydrogeochemical and isotopic investigations have been carried out in semi-arid environments of North Africa and the Mediterranean Basin to characterize groundwater quality and its controlling processes [

15,

16]. For instance, [

17] investigated the hydrogeochemical characteristics of groundwater in the Gafsa–Sidi Boubaker region,

southwestern Tunisia, highlighting the dominant influence of evaporitic formations and cation exchange processes. Likewise, several researchers have integrated GIS in their studies under similar conditions for better environmental assessment such as [

18,

19,

20].

Despite the abundance of geothermal manifestations in northeastern Algeria, the Teleghma system remains poorly documented compared to other regional geothermal fields. Most existing studies have focused on structural or geological aspects, with little attention to the integrated hydrochemical and isotopic characterization that can reveal recharge sources and water–rock interaction mechanisms.

The present study aims to fill this gap by (1) characterizing the geochemical and isotopic composition of the Teleghma geothermal waters; (2) identifying the main hydrochemical facies and their controlling processes; and (3) estimating the reservoir temperature and circulation depth using geothermometric and saturation index analyses.

Through this integrated approach, this study seeks to contribute to a better understanding of the origin and evolution of geothermal fluids in semi-arid environments of North Africa and their potential implications for sustainable geothermal resource development.

Study Area

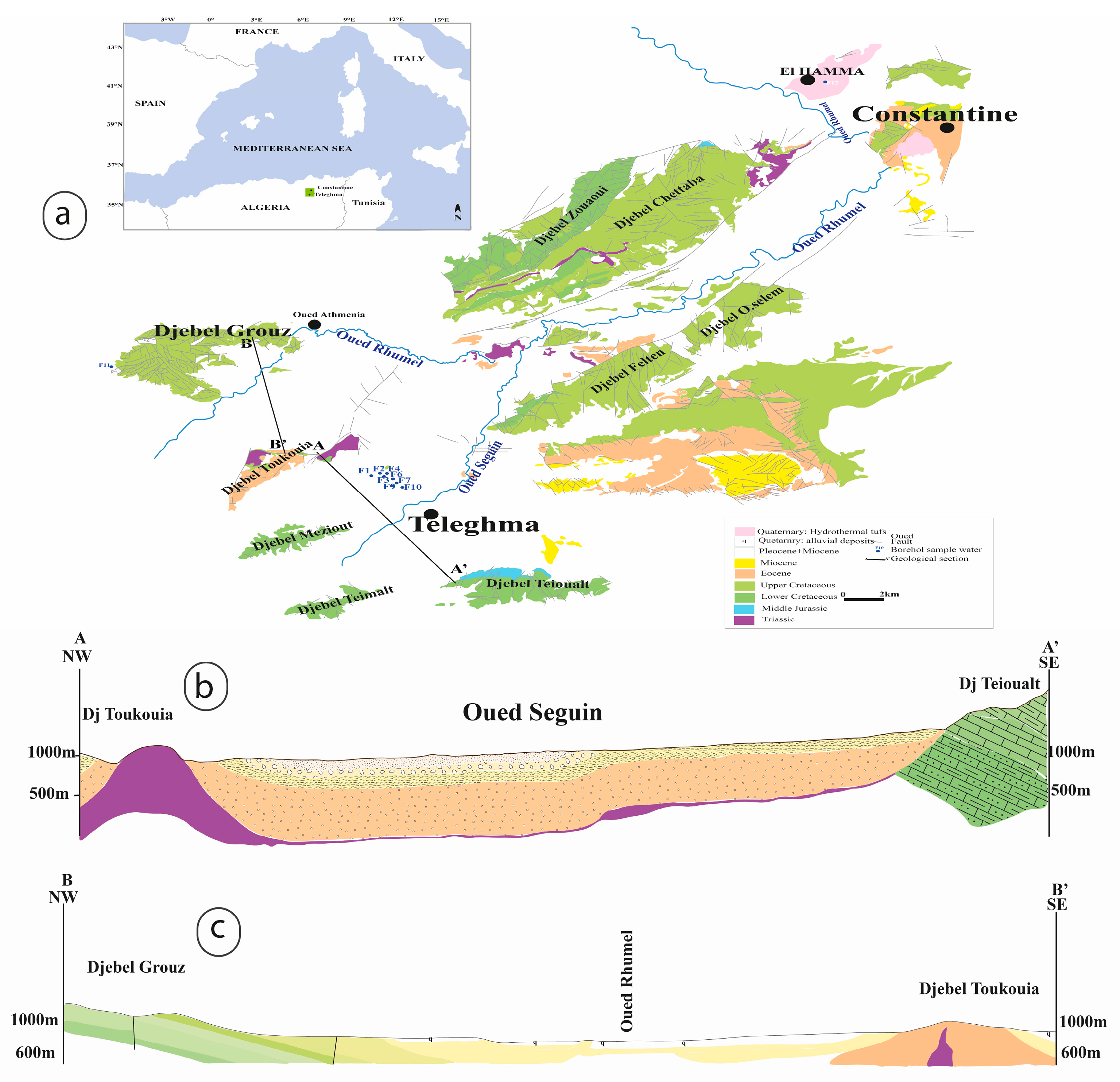

The study area is a basin surrounded by a series of relatively high reliefs (

Figure 1a). These include Djebel Felten (1113 m) to the northwest, Djebel Toukouia (1106 m) to the southeast, Djebel Meziout (1119 m) to the southeast, and the highest point, Djebel Teioualt (1286 m), to the south. The carbonate massifs that form the watershed are open, allowing them to feed the study area. The region’s hydrographic system is exoreic, meaning its water flows to the sea. Generally, temporary streams and surface water flow from the northwest to the southeast toward the plain.

Geologically, the Teleghma area is part of the Néritique Constantinoise, a region in eastern Algeria known for its karst massifs. These massifs are “horsts,” or uplifted blocks, surrounded by marl. The region’s tectonic history suggests that this massif is part of a larger “Constantinoise neritic domain” that lies beneath the surface. This domain is covered by Tellian nappes—large sheets of rock originating from the north—that are composed of marl and marly limestones. These nappes were thrust over the marly series to the south, and this bedrock slopes from south to north. A later tectonic phase of extension then broke the rock into horsts and grabens (uplifted and down-dropped blocks).

In the grabens, the karstification of carbonates has led to the formation of thermal aquifers. These massifs have experienced extensive karstification at their base due to deep-origin carbon dioxide (CO

2) [

21,

22]. This hydrothermal karst is characterized by large cavities and wide conduits in the saturated zone, through which thermal water drains. The aquifers discharge water that ascends through these conduits, driven by the pressure of CO

2. This water is notable for its high mineral content [

22].

According to [

23,

24], the current structures of the Constantine platform were formed during the Plio-Quaternary period. Around the city of Constantine, most of the springs are thermal. Some, like Hammam Grouz, emerge from limestone, but most, such as the Hamma Bouziane thermal springs and the Teleghma boreholes, emerge through the Neogene cover [

22] (

Figure 1b,c).

The Teleghma area is a basin surrounded by predominantly calcareous massifs: Djebel Felten, Djebel Teioualt, Djebel Tadjerout, and Djebel Maziout to the north and south. To the north are marly limestone massifs, with Djebel Toukouia dominating the Mio-Plio-Quaternary plain. This area is structured by a NE-SW-aligned barrier of Lutetian limestone resting on marls of the same age. The southeastern flank contains outcrops of Mio-Pliocene conglomerates, which are prone to intense erosion.

This zone is affected by two major tectonic faults running NE-SW and NW-SE. The presence of Triassic rock in an abnormal position amid recent deposits, along with a fault node overlying recent terrain, points to a deep structure. The Triassic formations are made up of heterogeneous evaporitic rocks, including red clays, gypsum, bipyramidal quartz, and white dolomite crystals [

25].

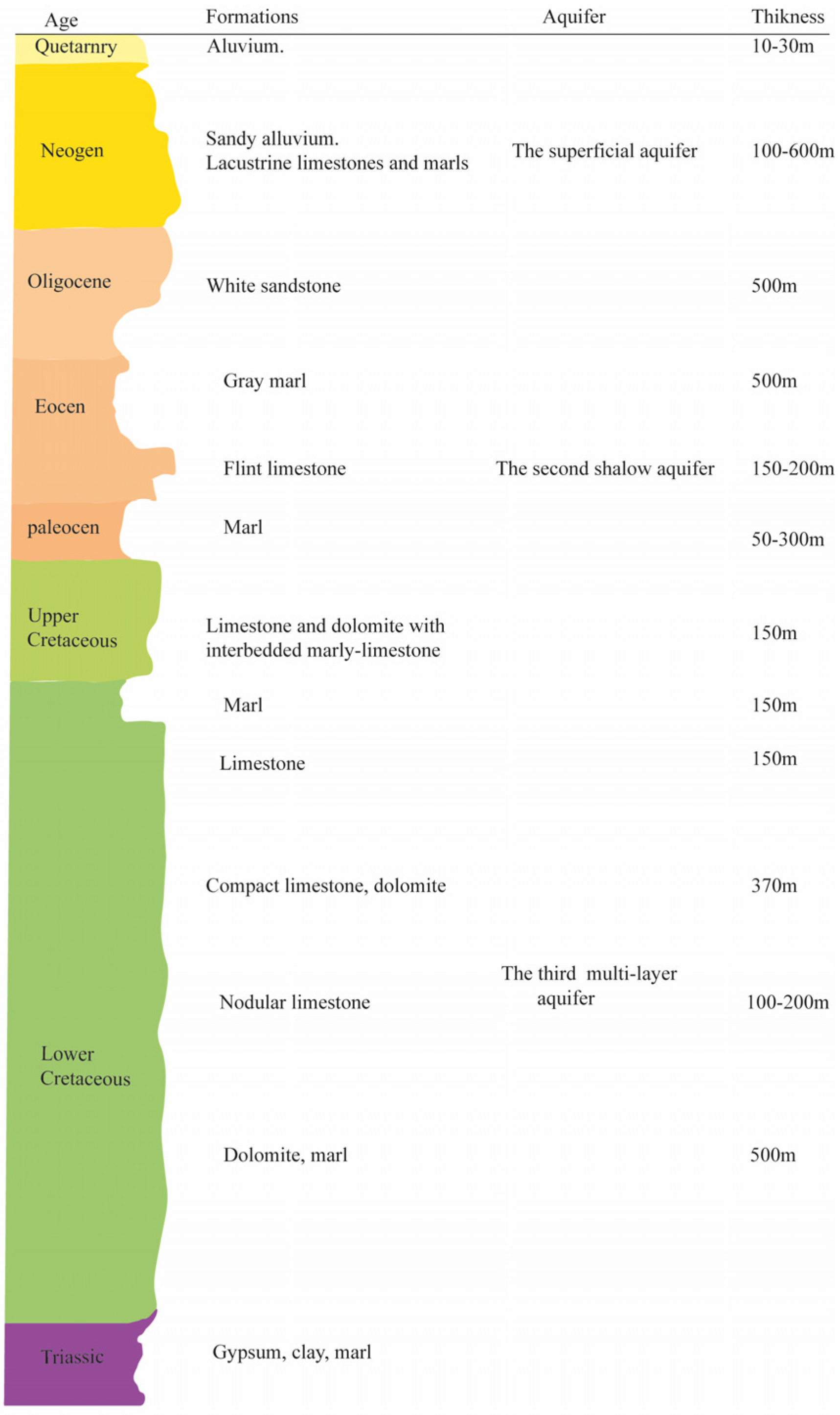

Regarding groundwater potential, the Teleghma region contains three aquifers of varying thicknesses such as the superficial Mio-Plio-Quaternary aquifer, which is a free aquifer within loose and fissured formations. It has a thickness of 100–600 m and is underlain by a marly substratum. The second aquifer, or the shallow Eocene aquifer, is partly confined and partly free. It is located within fissured limestone formations, with a thickness of 150 to 200 m, and rests on a more or less clayey marl substratum. Finaly, the deep Cretaceous multi-layer aquifer is formed as a confined aquifer embedded in fissured and karstic carbonate formations. It is 800 m thick, rests on marly substrata, and is known for its highly developed fissure permeability (

Figure 2).

The Ain Skhouna spring of Hamma emerged from the Quaternary alluvium in the Hamma Valley, situated between Cenomanian neritic limestone massifs. This valley corresponds to a small collapse trench that impacted the Lower Cretaceous and was later filled by Miocene continental deposits. The Hamma springs were drained when boreholes were installed.

The thermal spring of Hammam Grouz is partially located in the bed of the Oued Rhumel, within the Cenomanian limestone gorge on the southern side of the eastern end of the Djebel Grouz foothill, west of the Oued Rhumel (

Figure 1c). Water gushed from fractures in the limestone in a notable NE-SW direction [

3]. The emergence on the southern side was located in the middle of Plio-Villafranchian deposits. This is likely connected to a significant E-W fault that defines the southern boundary of the horst.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Analysis Method

Hydrochemical analyses were performed during a campaign in June 2022. We collected water from a total of 12 boreholes: 10 in the Teleghma area and the final 2 in the Grouz and Hamma zones. Temperature, pH, conductivity (EC), salinity (TDS), and dissolved oxygen were measured in situ using a HANNA (HI 98312) (HannaNorden AB, Kungsbacka, Sweden) and an AZ water quality meter (86031) (AZ Instrument Corp, Taichung, Taiwan).

Analyses of major elements were conducted at the Laboratory of Geology and Environment (LGE) in Constantine. The concentrations of major cations (Ca

2+, Mg

2+, Na

+, and K

+) were determined using atomic absorption spectrometry and spectrophotometry. Alkalinity was measured using standard titration methods, and chloride content was determined via the AgNO

3 titration method. Furthermore, heavy and trace elements were analyzed at the Algeria Nuclear Research Center of Birine (CRNB) using Ionic Liquid Chromatography (ILC) regarding F, Br, SO

42−, NO

2−, and Cl

− detections. Inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) was performed for measurements of Li, Sr, Ni, Zn, As, Pb, and Fe. Additionally, we also incorporated a dataset of chemical and isotopic compositions of water samples published by [

26] to supplement our study.

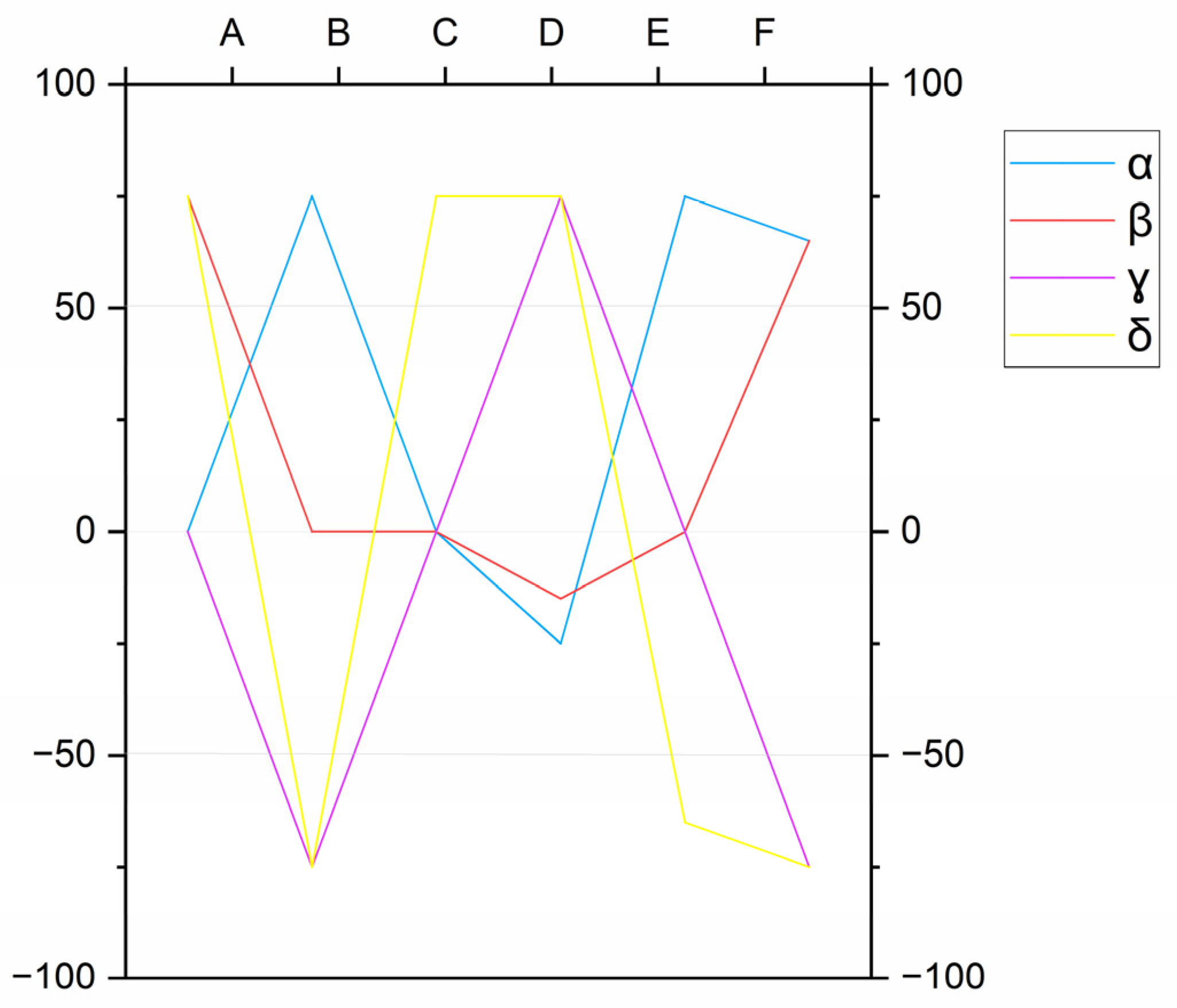

2.2. IIGR Method

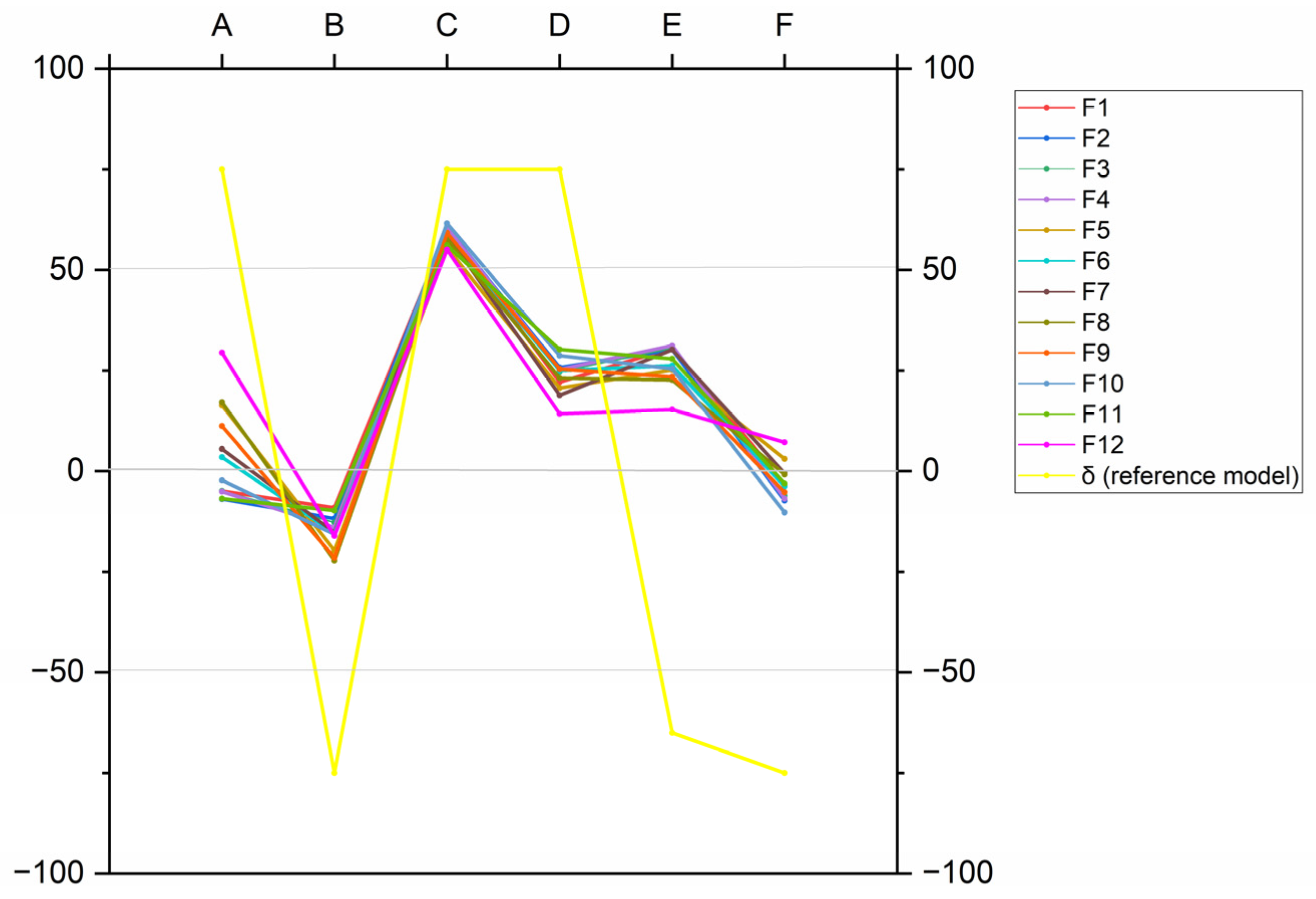

The IIGR method, which is well-established in the region, analyzes the concentration ratios of major elements, expressed in meq/L, to compute six distinct parameters (A, B, C, D, E, and F) [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Each of these parameters provides an indication of the water’s path through different geological formations. Specifically, Parameter A, calculated as 100 × ((HCO

3− − SO

42−)/Σ(anions)), differentiates between water from limestone areas and that from evaporitic layers. Parameter B, or 100 × ((SO

42−/Σ(anions)) − (Na

+/Σ(cations)), distinguishes sulfate-rich waters from sodium-rich waters in argillaceous marly sedimentary terrain. Parameter C, which is 100 × (Na

+/Σ(cations) + Mg

2+/Σ(anions)), separates waters originating from flysch or volcanic rock from those coming from evaporitic carbonate series or a schist–quartzite basement. Parameter D, represented by 100 × ((Na

+ − Mg

2+)/Σ(cations)), identifies waters that have circulated in dolomitic limestones. Parameter E, or 100 × ((Ca

2+ + Mg

2+)/Σ(cations) − HCO

3−/Σ(anions)), primarily differentiates between circulation in carbonate and sulfate reservoirs. Finally, Parameter F, calculated as 100 × (Ca

2+ − Na

+ − K

+)/Σ(cations), highlights the increase in potassium (K

+) content in the water. These normalized, unitless indices (ranging from −100 to +100) are used to position thermal waters within a specific rectangular diagram, which helps classify their lithological origin into one of four models (α, β, γ, δ) corresponding to evaporitic series, limestones, deep circulations in a crystalline basement, or clayey terrains, respectively (

Figure 3).

2.3. Geothermometers

Chemical geothermometers are essential tools for geothermal energy exploration and development. They operate on the principle that the chemical composition of geothermal fluids is influenced by the temperature of the reservoir. To accurately determine reservoir temperature, it is necessary to analyze the chemical signature of the fluids and consider factors such as cooling processes and reaction kinetics. This careful analysis ensures that temperature readings are interpreted correctly, leading to a more accurate estimate of the reservoir’s true temperature.

In this study, we used several geothermometers: cationic geothermometers (Na/Li and Mg/Li in mol/L; Na/K and Na-K-Ca in mg/L) and a silica geothermometer (quartz and chalcedony with SiO

2 expressed in ppm), as shown in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Formulas of the cationic and silica geothermometers used.

Table 1.

Formulas of the cationic and silica geothermometers used.

| Cationic Geothermometers | Equation | Reference | |

|---|

| Geothermometer Na/Li | | [32] | (1) |

| Geothermometer Mg/Li | | [33] | (2) |

Geothermometer Na/K

Geothermometer Na-K-Ca | | [34] | (3) |

| [35] | (4) |

| Silica geothermometers | | | |

| Quartz | | [36] | (5) |

| [37] | (6) |

| Chalcedony | | [38] | (7) |

2.4. Saturation Index Geochemical Modeling

The saturation index (SI) is a key measure for determining whether a mineral will dissolve or precipitate in a solution [

39]. We calculated the SI using PHREEQC Interactive software (version 3), which models mineral–solution reactions. This software performs simulations by using the physical and chemical data from water sample analyses as input [

10].

PHREEQC calculates saturation indices and tracks the transfer of matter between phases until equilibrium is reached, taking both reversible and irreversible geochemical reactions into account. The resulting saturation index offers valuable insights into mineral stability: positive values indicate that a mineral will precipitate, while negative values suggest it will remain dissolved.

Equilibrium is typically assumed for an SI range of −0.5 to 0.5. A value below −0.5 means the solution is undersaturated with respect to the mineral, whereas a value above +0.5 indicates supersaturation [

1,

40,

41].

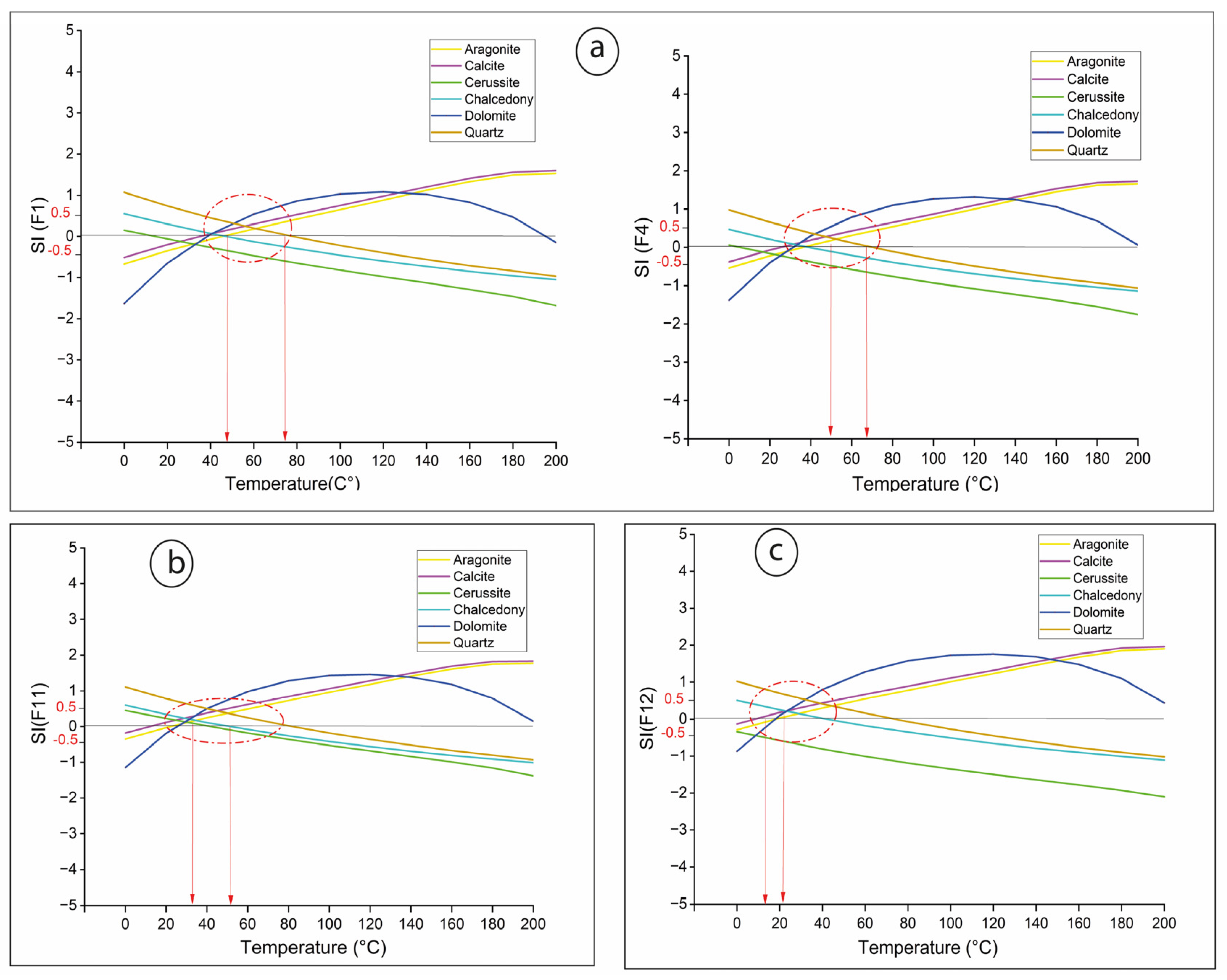

Another application of the saturation index is to model equilibrium states at various temperatures using PHREEQC [

1,

35]. This method allows for the estimation of geothermal reservoir temperatures by analyzing the saturation indices of key minerals. The simulation involves incrementally changing the temperature from 0 °C to 200 °C in 20 °C steps while keeping the chemical composition constant. The intersection point of the resulting graphs with the SI = 0 line determines the equilibrium temperature of the reservoir.

2.5. Inverse Modeling

Inverse modeling employs mathematical frameworks to replicate the geochemical processes occurring within a system. This method aids in comprehending the alterations in water chemistry as it traverses an environment and interacts with rocks and minerals [

10]. By analyzing the chemical makeup of water samples from various locations and considering the potential minerals present, models can be constructed to simulate these water–rock interactions. Accurately identifying the minerals involved and understanding their compositional changes are essential for developing a dependable model. PHREEQC utilizes a “balancing a solution” technique to fine-tune model parameters until they align with the observed water chemistry. However, achieving an exact match can be difficult due to uncertainties in data or limitations in the model. In such instances, enhancing data precision, modifying model constraints, or incorporating additional information might be required. The phreeqc.dat database was used for the calculations, with thermodynamic data outlined in a data block that includes the definitions of solutions, phases, and uncertainty limits. The concentrations of elements in solution and the mass of water in the solution are converted to molality. Additionally, the activity coefficients, referred to as gamma in the database, were calculated using the Davies equation for charged species [

10]:

Here,

A: constant at a given temperature;

Z: ionic charge;

the molar concentration of the ion.

It is important to remember that inverse modeling is a complex process, and a perfect match between the model and reality is not always achievable. Careful analysis and interpretation of results, while acknowledging uncertainties, are key to drawing meaningful conclusions. In this type of modeling, positive mole transfer values indicate mineral dissolution, and negative mole transfer values indicate mineral precipitation [

10].

3. Results

The hydrochemical analysis of the thermal water samples is presented in

Table 2. The measured temperature ranged from 32 °C to 49.3 °C, indicating thermal activity. However, these temperatures may not represent the actual reservoir temperatures. The highest temperatures, exceeding 41 °C, were recorded in the Teleghma and Hammam Grouz zones, while the lowest (32 °C) was in the Hamma region. Electrical conductivity increased from 1130 to 1370 µS/cm in the Teleghma and Hamma zones, with the highest value found in the Grouz Hammam zone. Total dissolved solids (TDS) ranged from 570 to 940 mg/L. The water was poorly oxygenated, with values between 0.5 and 1.2 mg/L, and had a neutral pH.

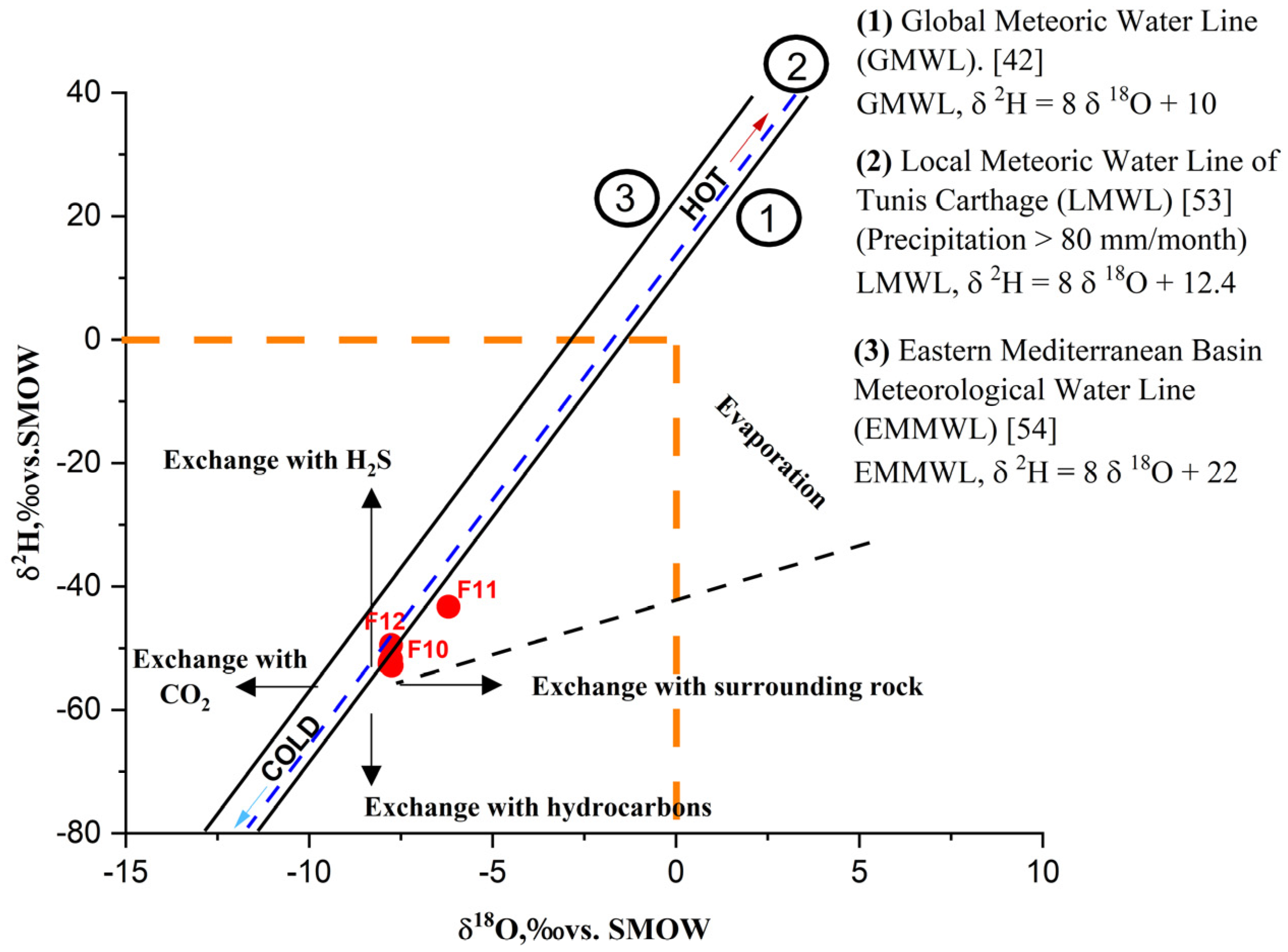

3.1. Isotopic Analysis

The origin of groundwater can be effectively determined using stable isotopes. In this study, we focused on the stable isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen, which remain relatively unchanged in medium- and low-temperature geothermal waters [

26]. The analysis of δD and δ

18O is particularly useful for tracing the water cycle [

9]. These isotopes are typically measured in relative terms, as their variations are sufficiently indicative. Isotope ratios are expressed in delta notation (δ) as follows:

where Rs represents the

18O/

16O or D/H ratio of the sample, and RSMOW is the corresponding ratio of Standard Mean Ocean Water (SMOW) [

13,

42].

SMOW serves as the baseline for comparison. According to isotopic analysis results from [

26] (

Table 3), δ

18O values range from –6.2‰ in Hammam Grouz to 7.81‰ in Teleghma, while δ

2H values range from –43.3‰ in Hammam Grouz to –52.57‰ in Teleghma.

The results were plotted on a δ

2H versus δ

18O diagram (

Figure 4) using the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL) as a reference, defined by [

42] as

The plot shows that most water samples lie close to the GMWL, with the exception of the Hamma sample, which is positioned directly on it. This distribution suggests that the geothermal waters of Teleghma, Grouz, and Hamma originate from meteoric precipitation, subsequently heated at depth, likely influenced by thermotectonic processes. According to [

7], the thermal circuit in the area is relatively short.

The δ

18O and δ

2H values suggest a meteoric origin, with slight enrichment due to evaporation or water–rock exchange. This isotopic behavior is comparable to that observed in the geothermal systems of Tozeur (Tunisia) and Hammam Debagh (Algeria), where prolonged water–rock interactions in Triassic formations lead to similar δ

18O shifts ([

43,

44]). Such isotopic enrichment, together with the moderate chloride content, indicates a circulation depth sufficient to acquire thermal characteristics but still influenced by partial mixing with shallower groundwater.

The isotopic enrichment patterns reflect the progressive interaction of meteoric recharge water with deep Triassic evaporitic formations. The slight deviation from the Global Meteoric Water Line suggests isotopic exchange with surrounding rocks at elevated temperatures. Such δ18O enrichment is consistent with geothermal systems influenced by prolonged residence times and partial evaporation effects during ascent.

3.2. Reservoir Lithology and Temperature Estimation

3.2.1. Reservoir Lithology

Based on the IIGR method, the thermal waters from the Teleghma, Grouz, and Hamma systems all correspond to the “δ” model, which indicates circulation within Triassic clay formations (

Figure 5). However, as the water rises through fractures and faults, its chemistry evolves, gradually altering the initial mineralization acquired in the karstic carbonate reservoir [

28].

3.2.2. Temperature Estimation Using Geothermometers

Table 4 lists the deep reservoir temperatures calculated using the cationic geothermometers mentioned in

Table 1. The Na/Li and Mg/Li geothermometers indicate temperatures above 100 °C, reaching up to 200 °C. These values are significantly higher than those from silica geothermometers, which suggest temperatures below 100 °C, ranging from 63 to 80 °C. The Na/K geothermometer also indicated temperatures above 100 °C, while the Na-K-Ca geothermometer provided values between 80 and 100 °C. The overestimation by cationic geothermometers (Mg/Li, Na/Li, and Na/K) can be attributed to the interaction of water with Triassic layers and evaporitic formations, which increases ion concentrations, even though sodium and lithium concentrations are relatively stable during ascent [

45]. Consequently, these cationic geothermometers may not accurately represent deep reservoir conditions. Conversely, silica geothermometers, particularly chalcedony, yielded underestimated values, likely due to the mixing of thermal water with shallow waters, which reduced silica concentrations.

The geothermometric results provide evidence for moderate to high subsurface temperatures, consistent with the hydrochemical patterns previously described. To further assess the equilibrium state of these waters, saturation indices for major minerals were calculated.

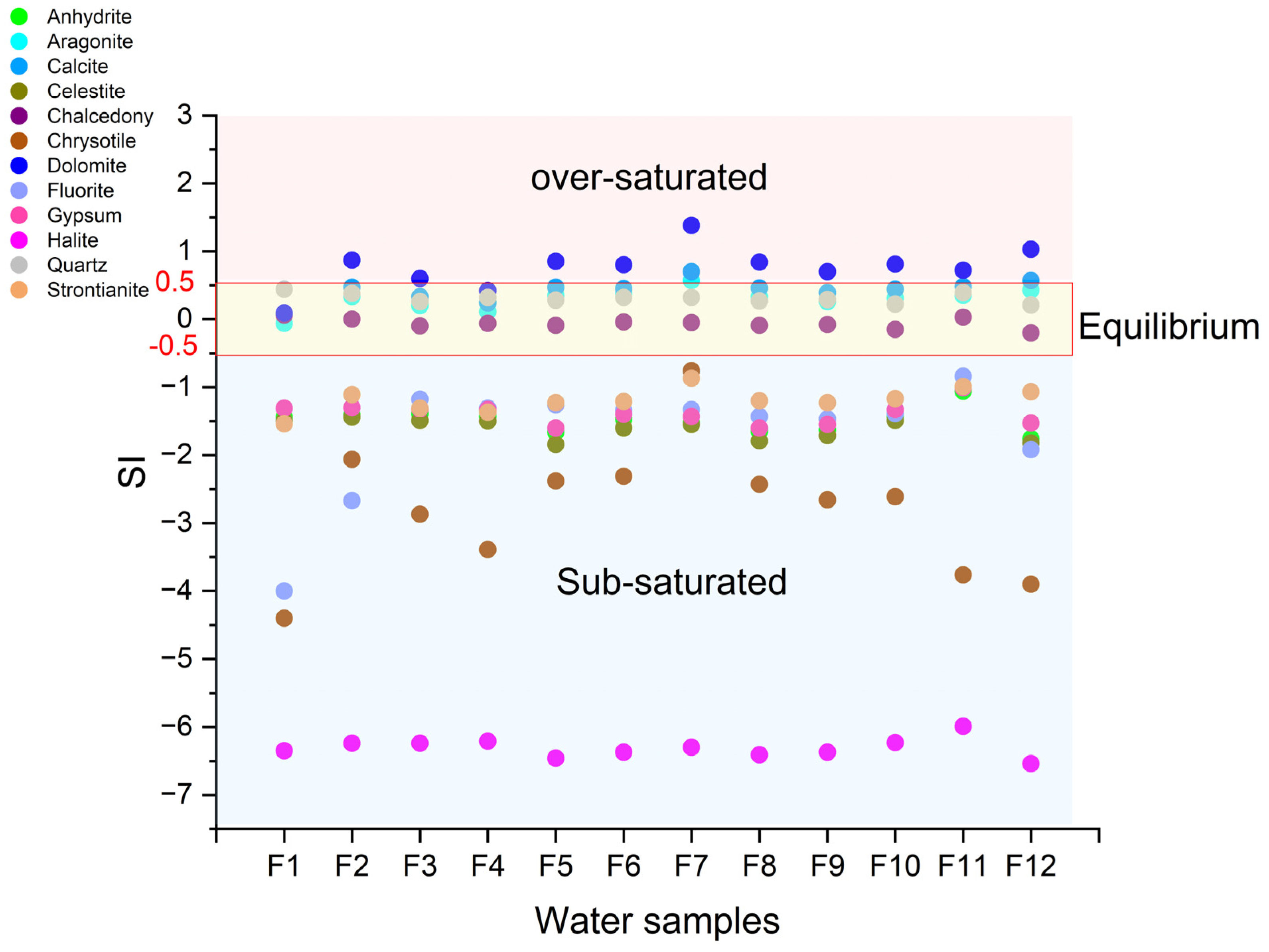

3.3. The Saturation Index (SI)

The saturation index (SI) was calculated for the thermal waters in the study area using concentrations of major and trace elements, pH, and emergence temperature (

Table 5). The geothermal water is oversaturated or near equilibrium with respect to carbonate minerals (aragonite, calcite, dolomite, and quartz), which means these minerals are prone to precipitation. Conversely, the water is undersaturated with respect to evaporitic minerals (halite) and, to a lesser extent, gypsum and anhydrite. The combination of carbonate oversaturation and evaporite undersaturation clearly indicates an active hydrochemical evolution. These patterns reveal the coexistence of two main geochemical processes: (1)

carbonate precipitation resulting from CO

2 degassing during ascent and (2)

evaporite dissolution contributing to elevated Na

+, Cl

−, and SO

42− concentrations. This dual control explains the observed spatial variability in both groundwater quality and flow dynamics within the Teleghma geothermal field. The coexistence of oversaturated carbonates and undersaturated evaporites indicates simultaneous precipitation and dissolution processes, a typical signature of geothermal systems influenced by CO

2 degassing and deep evaporitic interactions. Comparable geochemical behavior has been reported in Tozeur and F’Kirina plain [

46], supporting the idea that the hydrochemical evolution of the Teleghma geothermal system follows regional hydrothermal circulation trends observed in North Africa.

3.4. Inverse Modeling Scenarios

The most challenging aspect of inverse modeling is identifying the identity, composition, and spatiotemporal variations in reactive phases. We used geographical characteristics and the concept of chemical facies, which describes how water chemistry evolves as it flows through different geological formations. Following the classification by Chebotarev (1955) and Tôth (1999) in [

47], which distinguishes three stages of groundwater evolution (bicarbonate-dominant, sulfate-dominant, and chloride-dominant), we defined initial and final solutions for our models. The final solution is assumed to have a longer residence time or flow path than the initial one.

This study applied inverse modeling in three scenarios using two water samples per scenario.

Scenario 1: For the Teleghma region, we used sample F1 as the starting solution and F4 as the final solution (

Table 6). The calculation of ionic strength for the two solutions, sample F1 and sample F4 using Equation (9), yields values of 1.59 × 10

−2 mol/kgw for the initial solution and 1.65 × 10

−2 mol/kgw for the final solution. This slight variation suggests a change in the ionic composition between the two simulated states. This provides quantitative evidence that the model adjusted the ionic composition while remaining consistent with real conditions, which is crucial for validating the relevance of the inverse model.

Four models were generated, all showing halite dissolution with an average molar transfer of 1.12 mmol/kgw. This high value suggests significant dissolution. Model 2 identified halite as the primary reactive phase, leading to the conclusion that the Teleghma geothermal water type originates from halite dissolution. The second reaction phase involved the precipitation of calcite and dolomite, with low molar transfer rates of 3.0 × 10

−6 and 4.40 × 10

−5 mmol/kgw, respectively (

supplementray material scenario 1).

Scenario 2: This simulation modeled the relationship between the Grouz and Teleghma geothermal waters, with sample F11 from Hammam Grouz (representing the sulfate-dominant stage) as the initial solution and sample F1 from Teleghma (the chloride-dominant stage) as the final solution (

Table 7). The verification of ionic strength for the two samples presents 6.97 mol/kgw for the initial solution and 1.02 mol/kgw in the final solution; this means that the calculated solution shows a decrease in ionic concentration or less charged ions compared to the initial state. This fairly significant variation indicates that the model assumes a reduction in ionic interactions in the modified solution, which could mean the dissolution of less ionized phases or the precipitation of minerals containing highly charged ions (

supplementray material scenario 2).

Six models were generated, showing dominant precipitation of dolomite and calcite alongside the dissolution of gypsum, with no reaction for halite or anhydrite.

Scenario 3: We also simulated the relationship between the Teleghma and Hamma geothermal waters, proposing the F1 sample from Teleghma as the initial solution (in a high-plain recharge zone) and the F12 sample from Hamma as the final solution (the discharge zone). The results of simulation indicate that Phreeqc was unable to identify a set of parameters or a plausible scenario that satisfactorily reproduces the input data (

supplementray material scenario 3).

4. Discussion

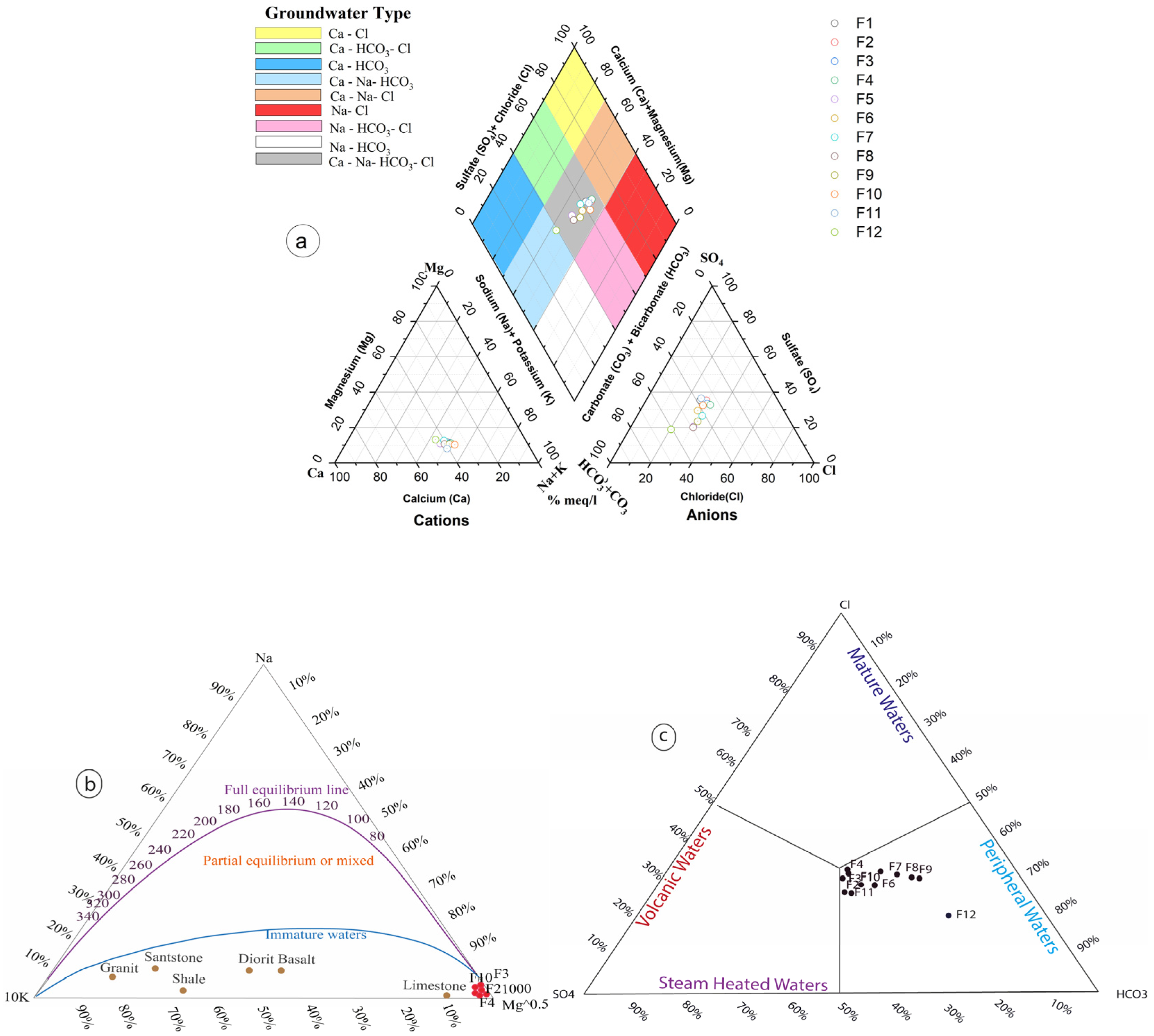

4.1. Water Types

Variations in the concentrations of dissolved species and overall mineralization suggest different classifications and flow conditions, depending on the rocks the water traversed. The major element concentrations are high and converging. The dominance sequences of cations and anions expressed on an equivalent-charge basis using r-values (

Table 2) present the chemical facies of water. For example, in the Teleghma geothermal water, the dominance of cations follows the order rNa + >rCa2 + > rMg2+, while the anions are dominated by chloride, following rCl

− > rSO

42− > rHCO

3−. This indicates a sodium chloride chemical facies, likely originating from evaporite formations. Similarly, the Hamma Grouz geothermal water exhibits a sodium sulfate facies, with the same cation dominance (rNa

+ > rCa

2+ > rMg

2+) but with anion dominance following rCl

− > rSO

42− > rHCO

3−. In contrast, the Hamma geothermal water is characterized by a calcic bicarbonate facies, dominated by carbonate minerals, with cations following rCa

2+ > rNa

+ and anions following rHCO

3− > rCl

− > rSO

42−, as shown in the Piper diagram (

Figure 6a).

According to [

48] and the Na-K-Mg ternary diagram, the relative concentrations of Na/1000, K/1000, and Mg0.5 indicate the temperature of a deep reservoir. As shown in (

Figure 6b), the thermal water samples are plotted very close to the magnesian pole. This classification suggests the water is immature or meteoric and undersaturated with respect to the equilibrium line, with low Na/K and high Mg content.

The central position of data points in the Cl-SO

4-HCO

3 classification diagram (Giggenbach,

Figure 6c) may represent an intermediate stage in the geochemical evolution of the thermal water. Water chemistry changes as it circulates and interacts with rocks. A central position can indicate that the water has not yet reached equilibrium with reservoir minerals, has undergone mixing during its ascent, or consists of younger fluids [

49].

Thermal waters generally have an increased capacity to dissolve silicate minerals like quartz, feldspars, and clays due to their high temperatures. However, the dissolved silica content in our samples is relatively low, fluctuating between 20 and 32 mg/L, which suggests restricted dissolution. A pH below eight may also indicate that silica ionization did not occur during the water’s ascent [

5]. In carbonate reservoirs, silica is rarely abundant because the dissolution primarily affects carbonate minerals [

14].

The trace elements Sr, Li, and F range from 0.1 to 2.38 mg/L, while Cr, Mo, Cd, Co, Fe, and Zn are present in very low concentrations. Low trace element concentrations generally indicate higher-quality thermal water with fewer contamination concerns, making it suitable for drinking, therapeutic treatments, and bathing. The low abundance of certain elements, such as zinc and chromium, might also be beneficial for specific therapeutic applications.

4.2. Isotopic Analysis

The deuterium excess parameter

provides additional insight into evaporation and permeability [

9]. In Teleghma and Grouz, d-values are below 10‰, indicating low evaporation and high permeability [

13]. In contrast, Hamma shows a d-value of approximately 12‰.

Previous studies [

7,

45,

50] suggest that in the Hamma hydrothermal system, recharge waters undergo isotopic exchange with host rocks at high temperatures during deep hydrothermal circulation. This process involves oxygen exchange between carbonates and water during high-temperature reactions.

4.3. The Saturation Index (SI)

The SI values were similar across all samples: most waters appear to be oversaturated with calcite (CaCO

3) and dolomite (CaMg(CO

3)

2), given the positive SI values. The SI for dolomite often exceeds 0.5, which is the limit for precipitation, while calcite values are at the boundary between equilibrium and oversaturation, ranging from 0.08 to 0.48. The geothermal water is in equilibrium with quartz and chalcedony (H

4SiO

4), as indicated by SI values between −0.5 and 0.5 (

Figure 7).

The highly negative SI values for halite (NaCl), averaging -6, indicate strong undersaturation, which favors rapid dissolution. This process contributes to the increased sodium and chloride concentrations in all water samples. While gypsum (CaSO4⋅2H2O), anhydrite (CaSO4), and chrysotile (Mg3SiO5) dissolve more slowly with increasing temperature, halite dissolves rapidly under these undersaturated conditions. The SI values for other dissolving phases, such as strontianite (SrCO3), celestite (SrSO4), and fluorite (CaF2), were approximately 1 and 2. The dissociation of these minerals is influenced by their interaction with evaporite and carbonate formations. The presence of fluoride also suggests inputs from deep sources.

The “equilibrium temperature” at which water equilibrates with its surrounding rocks provides a valuable indicator of a reservoir’s heat potential [

51]. Our SI modeling (

Figure 8) suggests that the saturation indices of the main minerals are near equilibrium at temperatures ranging from 50 to 70 °C for Teleghma (

Figure 8a), 35 to 55 °C for Hammam Grouz (

Figure 8b), and 15 to 20 °C for Hamma (

Figure 8c). These temperatures may represent the equilibrium temperature of a mixture of deep thermal groundwater and shallow cold groundwater. Thermal diffusion, combined with the long path traveled through Triassic formations, would decrease the water temperature and dilute elements like silica (SiO

2), while increasing concentrations of sodium (Na

+), chlorides (Cl

−), and sulfates (SO

42−) upon emergence.

4.4. Inverse Modeling

Scenario 1 indicates a slow precipitation rate, consistent with the possibility of solutions remaining supersaturated for extended periods [

1]. The balance of carbonate minerals was heavily influenced by the dissolution of Triassic diapiric evaporite formations, specifically halite. The models also showed no reaction for gypsum and anhydrite, suggesting conditions were not right for their reaction.

Scenario 2: Cation exchange involving clay minerals (NaX and CaX) was also a key process. In Model 1, the precipitation of calcite and dolomite was significant, with mole transfers of −3.64 × 10−1 and −2.54 × 10−2 mmol/kgw, respectively, accompanied by a high dissolution of gypsum (mole transfer of 3.88 × 10−1 mmol/kgw). This high dissolution explains the high concentrations of SO42− and Ca2+, which define the Hammam Grouz water type. The significant dissolution of gypsum can increase calcium concentrations, leading to the oversaturation of geothermal water with respect to calcite or dolomite in the presence of clay minerals. Cation exchange can also cause variations in cation ratios, influencing saturation levels. Model 6 was an exception, showing cationic exchange with NaX dissolution producing a slight increase in Na+ ions (mole transfer of 2.83 × 10−3 mmol/kgw) and the adsorption of Ca2+ (mole transfer of −1.42 × 10−3 mmol/kgw). The rate of mixing and fluid velocity can influence the distance required for groundwater to reach saturation with different mineral phases. Steady-state concentrations can exist where the rate of dissolution of one mineral is balanced by the precipitation of another.

Scenario 3 of inverse modeling describes errors where certain chemical equalities for CO3, Cl, Na, SO4, and alkalinity are not satisfied; in other words, the calculated concentrations do not sufficiently match the measured values. Furthermore, some inequalities, such as those related to alkalinity, are also not respected. The summary indicates that no model was found (number of models found: 0), that there is at least one set of mineral phases that is not feasible, and that the Cl1 routine was called three times without success. In practice, this means that the program could not adjust the quantities of minerals and other parameters to adequately explain the differences in chemical composition between the initial and final waters, which may be due to inconsistent data or an inadequate choice of mineral phases.

In fact, the influence of cold water in the Hamma hydrothermal system significantly influence the reaction processes. The input of other species, for example isotopes with other samples from the Hamma zone, in the inverse modeling may help to confirm if there is direct connection between the two systems.

The results of our inverse modeling provide specific information about the mineral phases and chemical exchange processes responsible for the evolution of our thermal water’s chemical facies. In the Teleghma system, halite dissolution is the main driver of water chemistry evolution. On a regional scale, between the Grouz and Teleghma thermal waters, the dissolution of gypsum and cationic exchange are the key processes. These findings indicate that the hydrothermal systems of Grouz and Teleghma share similar characteristics. The geochemical evolution observed in the Teleghma geothermal system, characterized by Na–Cl facies and evaporite dissolution, aligns closely with findings from other semi-arid geothermal or deep aquifer systems in North Africa and the Mediterranean region [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. This convergence underscores the regional influence of Triassic evaporitic sequences and fault-controlled hydrothermal circulation on groundwater composition.

5. Geothermal Resource Management

The findings of this study have several important implications for the sustainable management of geothermal resources in the Teleghma region. The characterization of the thermal waters as immature, meteoric in origin, and circulating along deep faults highlights the vulnerability of this resource to changes in recharge patterns and potential contamination from surface activities.

The relatively low temperatures (41–49.3 °C) and moderate flow rates suggest that the Teleghma geothermal system is best suited for direct-use applications, such as therapeutic bathing, balneology, or low-temperature heating. However, careful management is required to ensure that extraction rates do not exceed the natural recharge capacity of the system, which could lead to a decline in water levels and/or a reduction in water temperature. A comprehensive monitoring program, including regular measurements of temperature, flow rate, and chemical composition, is essential to track the health of the resource and detect any early signs of overexploitation.

The observed mixing with shallow, cooler waters indicates that the deep reservoir temperature may be underestimated by conventional geothermometers. Therefore, caution should be exercised when evaluating the potential for geothermal energy production. A more detailed understanding of the mixing processes and the true reservoir temperature is needed to accurately assess the economic viability of different geothermal applications. Advanced geochemical modeling, incorporating mixing models and accounting for mineral saturation indices, can provide valuable insights into the subsurface conditions.

The identification of halite dissolution as a key process influencing the chemical evolution of the thermal waters highlights the potential for increasing salinity over time. This could pose a challenge for certain applications, such as irrigation or potable water use. Therefore, careful monitoring of salinity levels is crucial, and appropriate water treatment technologies may be necessary to mitigate the risk of salinization.

Finally, the likely connection between the Teleghma and Hammam Grouz geothermal systems underscores the importance of managing these resources in an integrated manner. Any development activities in one area could potentially impact the other, so a coordinated approach is essential to ensure the long-term sustainability of both systems. Furthermore, given that these waters emerge from a karstic carbon reservoir, it is imperative to protect and preserve the integrity of karstic systems.

6. Conclusions

In the high plains of the Neritic unit of Constantine, the Teleghma region is characterized by immature thermal waters of meteoric origin, as indicated by the Giggenbach diagram and isotopic signatures (δD and δ18O). These waters emerge from a karstic carbonate reservoir at temperatures of 41–49.3 °C, following a short hydrothermal circuit along highly permeable deep faults linked to recent tectonic activity. At the surface, they display a sodium–chloride type, slightly alkaline pH (<8), and conductivity of 1190–1390 µS/cm. Teleghma’s thermal waters have comparatively better quality, with low concentrations of trace elements such as Cr, Mo, Cd, Co, Fe, and Zn, making them suitable for therapeutic and recreational uses.

Reservoir lithology, assessed using the IIGR method, corresponds to a type γ diagram, suggesting that the thermal waters ascend through clay formations that influence their chemical composition, as supported by saturation index results. Evaporitic formations, present as diapirs in Teleghma, further affect water chemistry, contributing to secondary mineralization. This is reflected in the undersaturation of evaporites and oversaturation of carbonates. SI modeling indicates equilibrium temperatures of 50–70 °C for Teleghma waters, 35–55 °C for Hammam Grouz, and 15–20 °C for Hamma. The data suggest mixing with shallow, cooler waters, which can lead to both under- and overestimation of deep reservoir temperatures by geothermometers.

Inverse modeling identifies halite dissolution as the main driver of chemical evolution in the Teleghma geothermal system. At a broader scale, gypsum dissolution and Ca–Na cation exchange dominate, with no significant halite interaction. Overall, the results indicate that Teleghma and Grouz waters originate from the same hydrothermal system. However, determining their relationship to the Hamma system will require further isotopic analyses, such as tritium (3H), strontium isotopes (87Sr/86Sr), and dissolved gases.

While the Teleghma thermal waters exhibit promising characteristics for therapeutic and recreational uses, a comprehensive monitoring program is essential to ensure long-term sustainability. Furthermore, the potential for direct-use geothermal applications should be investigated to reduce reliance on conventional energy sources. Further research is also warranted, including high-resolution geophysical surveys to delineate the subsurface fault structures, and additional isotopic analyses (3H, 87Sr/86Sr, dissolved gases) to clarify the relationships between Teleghma, Hammam Grouz, and Hamma. Finally, understanding the specific sources of halite dissolution contributing to the salinity requires further investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.E.I.B.; methodology, N.E.I.B., F.B., and A.B.; software, A.B., and F.B.; validation, F.B. and N.E.I.B.; formal analysis, N.E.I.B. and F.B.; investigation, N.E.I.B.; resources, N.E.I.B., F.B., and A.B.; data curation, A.B., F.B., and N.E.I.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.E.I.B. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, N.E.I.B., A.B., and F.B.; visualization, A.B., N.E.I.B., and F.B.; supervision, F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like give special thanks to UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and IUGS (International Union of Geothermal Sciences) in the framework of the International Geoscience Program (IGCP 636). The authors would like to express their thanks to the anonymous reviewers of this manuscript for their critical review and helpful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bouaicha, F. Le Géothermalisme de la Région de Guelma. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Constantine 1, Constantine, Algeria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Athamena, M. Étude des Ressources Thermales de L’ensemble Allochtone Sud Sétifien. Master’s Thesis, University of Batna, Batna, Algeria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guige, S. Hydrogeochemistry and geothermometry of thermal water from northeastern Algeria. Geothermics 2018, 75, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, H. Le Thermalisme de l’Est Algérien. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Algiers, Algiers, Algeria, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Issaadi, A. Le Thermalisme Dans Son Cadre Géostructural, Apports à la Connaissance de la Structure Profonde de l’Algérie et de Ses Ressources Géothermales. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Algiers, Algiers, Algeria, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchareb-Haouchine, F.Z. Apports de la Géothermométrie et Des Données de Forages Profonds à L’identification des Réservoirs Géothermiques de l’Algérie du Nord: Application à la Région du Hodna. Master’s Thesis, University of Sciences and Technology (USTHB), Algiers, Algeria, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dib, H. Guide Pratique des Sources Thermales de l’Est Algérien; National Geological Survey: Algiers, Algeria, 2008; Volume 15, 106p.

- Li, J.; Sagoe, G.; Yang, G.; Liu, D.; Li, Y. Application of geochemistry to bicarbonate thermal springs with high reservoir temperature: A case study of the Batang geothermal field, western Sichuan Province, China. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2018, 371, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, H.; Xiang, T.; Li, C.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y. Hydrogeochemical Evolution Mechanism of Carbonate Geothermal Water in Southwest China. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Appelo, C.A.J. Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3, a computer program for speciation, batch reaction, one-dimensional transport and inverse geochemical calculations. In U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2013; Book 6, Chapter A43. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, C.; Pizzino, L.; Cinti, D.; De Gregorio, S.; Favara, R.; Galli, G.; Giudice, G.; Gurrieri, S.; Quattrocchi, F.; Voltattorni, N. Inverse and forward modelling of groundwater circulation in a seismically active area (Monferrato, Piedmont, NW Italy): Insights into stress-induced variations in water chemistry. Chem. Geol. 2008, 248, 14–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, Y.; Tian, J.; Cheng, Y.; Pang, Z.; Gong, Y. Geochemistry of geothermal fluid with implications on circulation and evolution in Fengshun-Tangkeng geothermal field, South China. Geothermics 2022, 98, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Li, P.; Wang, L.; He, X.; Zhang, L. Hydrochemical characteristics, hydrochemical processes, and recharge sources of the geothermal systems in Lanzhou City, northwestern China. Urban Clim. 2022, 43, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, C.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, T.; Chen, Z.; Xie, H.; Xiang, T. Hydrogeochemical signatures origin of a karst geothermal reservoir: The Sinian Dengying Formation in northern Guizhou, China. Geosci. J. 2023, 28, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guendouz, A.; Moulla, A.S.; Edmunds, W.M.; Zouari, K.; Shand, P.; Mamou, A. Hydrogeochemical and isotopic evolution of water in the Complexe Terminal aquifer in the Algerian Sahara. Hydrogeol. J. 2003, 11, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaoui, Z.; Gentilucci, M.; Wederni, K.; Hidouri, N.; Hamedi, M.; Dhaoui, Z.; Hamed, Y. Hydrogeochemical and stable isotope data of the groundwater of a multi-Aquifer system in the Maknessy Basin (Mediterranean Area, Central Tunisia). Hydrology 2023, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, Y. The hydrogeochemical characterization of groundwater in Gafsa-Sidi Boubaker region (Southwestern Tunisia). Arab. J. Geosci. 2013, 6, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A.; Hadji, R.; Bâali, F.; Houda, B.; Redhaounia, B.; Zighmi, K.; Legrioui, R.; Brahmi, S.; Hamed, Y. Conceptual model for karstic aquifers by combined analysis of GIS, chemical, thermal, and isotopic tools in Tuniso-Algerian transboundary basin. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghali, T.; Marah, H.; Qurtobi, M.; Raibi, F.; Bellarbi, M.; Amenzou, N.; El Mansouri, B. Geochemical and isotopic characterization of groundwater and identification of hydrogeochemical processes in the Berrechid aquifer of central Morocco. Carbonates Evaporites 2020, 35, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahiaoui, S.; Meddi, M.; Razack, M.; Boufekane, A.; Bekkoussa, B.S. Hydrogeochemical and isotopic assessment for characterizing groundwater quality in the Mitidja plain (northern Algeria). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 80029–80054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiffait, P.E.; Quinif, Y.; Vila, J.M. Histoire géologique et karstification des massifs néritiques constantinois (Algérie). Actes Symp. Grenade Ann. Spéléol. 1975, 30, 619–627. [Google Scholar]

- Djebbar, M. Caractérisation du Système Karstique Hydrothermal Constantine-Hamma Bouziane-Salah Bey Dans Le Constantinois Central (Algérie Nord Orientale). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Constantine 1, Constantine, Algeria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, J.M. Définition de la nappe néritique constantinoise. Élément structural majeur de la chaîne alpine d’Algérie orientale. C. R. Soc. Géol. Fr. 1978, 42, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arris, Y. Étude Tectonique et Microtectonique des Séries Jurassiques À Plio-Quaternaires du Constantinois Central (Algérie Nord-Orientale): Caractérisation des Différentes Phases de Déformation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Henri Poincaré-Nancy 1, Nancy, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Fliert, J.R. Étude géologique de la région d’Oued Athemania (Algérie). Bull. Serv. Carte Géol. Algérie 1952, 3, Alger. [Google Scholar]

- Feraga, T.; Pistre, S. Qualitative and Comparative Study of Different Methods of Interpolation for the Mapping of Groundwater Salinity: Case Study of Thermal Waters Used for Irrigation in Northeastern Algeria. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2021, 9, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, F.; Scandiffio, G.; Panichi, C. Some observations on the chemical classification of groundwater. Geothermics 1983, 12, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchareb-Haouchine, F.Z.; Boudoukha, A.; Haouchine, A. Hydrogéochimie et géothermométrie: Apports à l’identification du réservoir thermal des sources de Hammam Righa, Algérie. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2012, 57, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudoukha, A.; Athamena, M. Caractérisation des eaux thermales de l’ensemble Sud sétifien. Est Algérien. Rev. Sci. Eau 2012, 25, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bouaicha, F.; Dib, H.; Bouteraa, O.; Manchar, N.; Boufaa, K.; Chabour, N.; Demdoum, A. Geochemical assessment, mixing behaviour, and environmental impact of thermal waters in the Guelma geothermal system, Algeria. Acta Geochim. 2019, 38, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmarce, K.; Hadji, R.; Zahri, F.; Khanchoul, K.; Chouabi, A.; Zighmi, K.; Hamed, Y. Hydrochemical and geothermometric characterisation of a geothermal system in a semiarid dry climate: A case study of Hamma spring (Northeast Algeria). J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2021, 182, 104285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharaka, Y.K.; Lico, M.S.; Law-Leory, M. Chemical geothermometers applied to formation waters, Gulf of Mexico and California basins. AAPG Bull. 1982, 66, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharaka, Y.K.; Mariner, R.H. Chemical geothermometers and their applications to waters from sedimentary basins. In Thermal History of Sedimentary Basins; S.C.P.M Special Volume; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Can, I. A new improved Na/K geothermometer by artificial neural networks. Geothermics 2002, 31, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, R.O.; Truesdell, A.H. Procedure for estimating the temperature of a hot-water component in a mixed water by using a plot of dissolved silica versus enthalpy. J. Res. U.S. Geol. Survey 1977, 5, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, R.O. Chemical geothermometers and mixing models for geothermal systems. Geothermics 1977, 5, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.P. Silica solubility geothermometers for hydrothermal systems. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Water-Rock Interaction, Villasimius, Italy, 10–15 June 2001; Volume 1, pp. 349–352. [Google Scholar]

- Arnórsson, S.; Gunnlaugsson, E.; Svavarsson, H. The geochemistry of geothermal waters in Iceland. Chemical geothermometry in geothermal investigations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1983, 47, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.-A.; Shao, H.; Tang, L.; Deng, B.; Li, H.; Wang, C. Hydrogeochemistry and geothermometry of geothermal waters from the Pearl River Delta region, South China. Geothermics 2021, 96, 102164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foued, B.; Hénia, D.; Lazhar, B.; Nabil, M.; Nabil, C. Hydrogeochemistry and geothermometry of thermal springs in the Guelma region, Algeria. J. Geol. Soc. India 2017, 90, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmari, H.; Bouaicha, F.; Aberkane, S.; Filali, A.; Blessent, D.; Badache, M. Geological context and thermo-economic study of an indirect heat ORC geothermal power plant for the northeast region of Algeria. Energy 2024, 290, 130323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H. Isotopic variations in meteoric waters. Science 1961, 133, 1702–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahim, F.B.; Boughariou, E.; Makni, J.; Bouri, S. Evaluation of groundwater hydrogeochemical characteristics and delineation of geothermal potentialities using multi criteria decision analysis: Case of Tozeur region, Tunisia. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 113, 104504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenaker, H.; Houha, B.; Vincent, V. Hydrogeochemistry and geothermometry of thermal water from north-eastern Algeria. Geothermics 2018, 75, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraga, T. Étude Quantitative et Qualitative des Eaux Thermales du Nord Est Algérien. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rahal, O.; Gouaidia, L.; Fidelibus, M.D.; Marchina, C.; Natali, C.; Bianchini, G. Hydrogeological and geochemical characterization of groundwater in the F’Kirina plain (Eastern Algeria). Appl. Geochem. 2021, 130, 104983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montcoudiol, N. Contribution de L’hydrogéochimie à la Compréhension des Écoulements D’eaux Souterraines en Outaouais, Québec, Canada. Ph.D. Thesis, Universities of Quebec and Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Giggenbach, W.F. Chemical techniques in geothermal exploration. In Application of Geochemistry in Geothermal Reservoir Development; D’Amore, F., Ed.; UNITAR/UNDP Centre on Small Energy Resources: Rome, Italy, 1991; pp. 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Wang, G.; Ma, F.; Zhang, W.; Lin, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, H. Geochemical Characteristics of Geothermal Fluids of a Deep Ancient Buried Hill in the Xiong’an New Area of China. Water 2022, 14, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djebbar, M.; Bencheikh-lehocine, M.; Bakalowicz, M.; Meniai, A.H. Identification hydrogéochimique du Karst hydrothermal Constantinois (Algérie Nord-Oriental). Sci. Technol. B 2004, 22, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Benmarce, K.; Zighmi, K.; Hadji, R.; Hamed, Y.; Gentilucci, M.; Barbieri, M.; Pambianchi, G. Integration of GIS and water-quality index for preliminary assessment of groundwater suitability for human consumption and irrigation in semi-arid region. Hydrology 2024, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueroui, Y.; Touati, H.; Bousbia, A.; Guettaf, M.; Maoui, A. Hydrogeochemical and environmental isotopes study of northeastern Algerian thermal waters. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).