1. Introduction

Technological development has profoundly transformed everyday life and provides a wide range of conveniences, such as the incorporation of smart devices into domestic spaces that shape how individuals interact with their environments. These developments have facilitated substantial societal progress, and contemporary younger generations now benefit from innovations that have become deeply embedded in daily routines, often without conscious recognition. This development, however, was not combined with environmental protection measures, and now both the environment and humans are faced with severe effects linked to environmental problems [

1]. While these effects are becoming more intense, overconsumption remains a significant part of modern life [

2,

3]. The Internet plays a significant role in overconsumption patterns by fostering the frequent purchase of non-essential products, driven by pervasive advertising, influencer culture, and algorithmic targeting.

The need to address environmental problems is clear, and now, sustainability occupies a significant place in public dialogue and policy agendas. It is widely acknowledged that institutional policies, along with individual actions concerning environmental issues, are critical in achieving meaningful change. As people are inextricably linked to the natural environment and each behavior has an impact on it, changing behavior patterns should be an integral part of every strategy to mitigate the excessive pressure on the environment [

4]. As they do not require any particular training or knowledge, energy saving and recycling are practices that people can easily apply in their everyday lives [

5]. In order to promote the wide adoption of these behaviors, a combination of appropriate information, awareness, and education is necessary.

Recycling is based on the principle of returning waste to the production cycle and involves the process of transforming waste materials into new products. It may thus be seen as a crucial response to the widespread problems of overconsumption and insufficient waste management worldwide [

6,

7]. According to the European Environmental Agency, each European citizen produces around 5 tons of waste, but only 40.8% of municipal waste is recycled [

8]. The textile industry, through the proliferation of fast fashion, is a major contributor to waste as the production of low-cost clothing at a rapid pace accelerates waste generation [

9]. In 2015, the European Council presented an action plan for the circular economy in which the reuse and recycling of useful materials were recognized as a key issue. The objectives of the plan involved strengthening the EU’s independence from raw material imports and the use of natural resources in sustainable ways. In 2018, the European Council further strengthened recycling targets since these were considered key factors for the circular economy. The target for the recycling of municipal waste was set to 55% by 2025, which should be increased to 60% by 2030 and to 65% by 2035. Member states are thus obliged to carry out separate collection of textiles, hazardous household waste, and organic products by 2025, while separate collection of paper, glass, plastic, metal, and cardboard is already in force. In addition, recycling targets are set for packaging materials (plastic, paper, glass, aluminum, wood, ferrous metals), which should increase 5–10% by 2030 [

10]. In relation to the study area, Greece has exerted great efforts to increase the rate of recycling, but has not achieved the same progress as other EU member states [

5]. Local governmental authorities in Greece have increasingly aligned their waste management strategies with broader European Union directives aimed at promoting circular economy principles. Municipalities have thus implemented a wide range of policies and regulatory measures to facilitate and enhance the collection, sorting, and recycling of waste. This includes the gradual imposition of bans on the disposal of certain categories of waste in landfills. In addition, the introduction of separate waste collection streams, public awareness campaigns, and economic incentives is implemented at the local level to increase citizen participation in recycling practices. Despite these advancements, significant regional disparities persist in implementation and performance, often due to variations in infrastructure, administrative capacity, and public engagement [

11].

Apart from recycling, energy saving is another necessary step toward sustainability [

12,

13]. People are highly dependent on energy, which is required in every activity of modern society [

14]. The largest share of energy is still derived from fossil fuels, whose combustion, however, produces greenhouse gases, which in turn contribute to climate change. Acknowledging the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to reinforce its energy independence, the European Commission on 18 May 2022 announced the REpowerEU plan, which reinforces the Green Deal’s aim of making the EU the world’s first climate-neutral continent by 2050. According to this plan, the EU seeks its independence from Russia and focuses on different ways of energy supply, energy saving, and energy production from renewable sources. Energy saving is one of the most important energy strategies and the EU wants to reduce the amount of energy consumption by about 13% [

15]. However, it does not suffice to rely solely on the EU’s policies; it is necessary to spread knowledge on recycling and energy saving throughout society and seek effective ways to change people’s behavior in line with the new objectives [

9,

16].

Research has focused on citizens’ knowledge, opinions, attitudes, and behaviors regarding recycling and energy saving. For example, the studies of Byrne et al. [

17], De Young [

18], Mtutu and Thondhlana [

4], and Altikolatsi et al. [

19] indicated that most citizens are engaged in recycling practices and implement recycling practices on a frequent basis. On the other hand, research by Thomas et al. [

20] and Zen et al. [

21] captured much lower citizen engagement with recycling. The profile of frequent recyclers is also interesting to note; most recyclers are women [

22,

23] and, in terms of their family status, most are cohabiting or married [

22,

24]. As for age, however, no specific age range has been found; there is a volume of research showing that older people recycle more often [

4,

25], while another stream of the literature has reported that both the younger and older age ranges are committed to recycling [

22]. At the same time, the age group 31–40 has been identified as the most active in recycling [

26]. Income and educational level are other variables that have been found to be highly influential in terms of recycling [

21,

27]. Several studies have found similar results regarding which materials citizens recycle the most; most people recycle paper and plastic, and fewer people recycle glass, aluminum, batteries, or other recyclable materials [

4,

18,

20,

27].

On a general note, citizens have been found to express positive views on recycling and energy-saving in various studies. In a considerable number of studies, citizens were found to acknowledge these practices as important and ones that can contribute to the mitigation of environmental problems [

18,

19,

20,

28]. With that being said, findings on citizens’ knowledge are somewhat varied. For example, Zerinou et al. [

29] and Liao et al. [

30] found that citizens were aware of the limited availability of natural resources, while Mtutu and Thondhlana [

4] found that citizens were able to recognize which materials are recyclable and non-recyclable. On the other hand, in the study of Szaba et al. [

31], a significant percentage of respondents demonstrated limited knowledge about renewable energy sources and especially geothermal energy, while the conclusion in the study of Coco Chin et al. (2023) was that citizens lacked basic knowledge [

26]. In general, the most widely adopted practices involve turning off the lights when not using a room [

32,

33], recycling [

33], and turning off the laptop when not in use [

34]. In the study of Zerinou et al. [

29], which was conducted in a city in the same prefecture as the study area of this study, the majority of respondents reported checking the energy label when buying an appliance, choosing mostly class A appliances, setting the temperature on the thermostat between 20 °C to 22 °C, and watering their garden or balcony plants at night. A similarly high level of adoption of environmentally friendly practices was observed by Żywiołek et al. [

32]; specifically, 47% of respondents reported opting for energy-efficient light bulbs, 17% having installed insulation on walls and roofs, and 38% having installed energy-efficient window frames. Similarly, in the study of Jia et al. [

35], the majority of the participants had installed energy-saving heating and air conditioning devices, while about half participants owned low-emission vehicles. Moreover, regarding the practices related to electronic devices, when not using the laptop and the TV, respondents in the study of Zerinou et al. [

29] reported turning off these devices from the power source, while in the study of Mtutu and Thondhlana [

4], a low percentage of participants always turned off the laptop when not in use. Finally, Zerinou et al. [

29] observed that citizens expressed more trust in scientists on environmental matters, followed by citizen groups. Regarding trust, remarkably low trust levels were recorded for political parties in another study [

36].

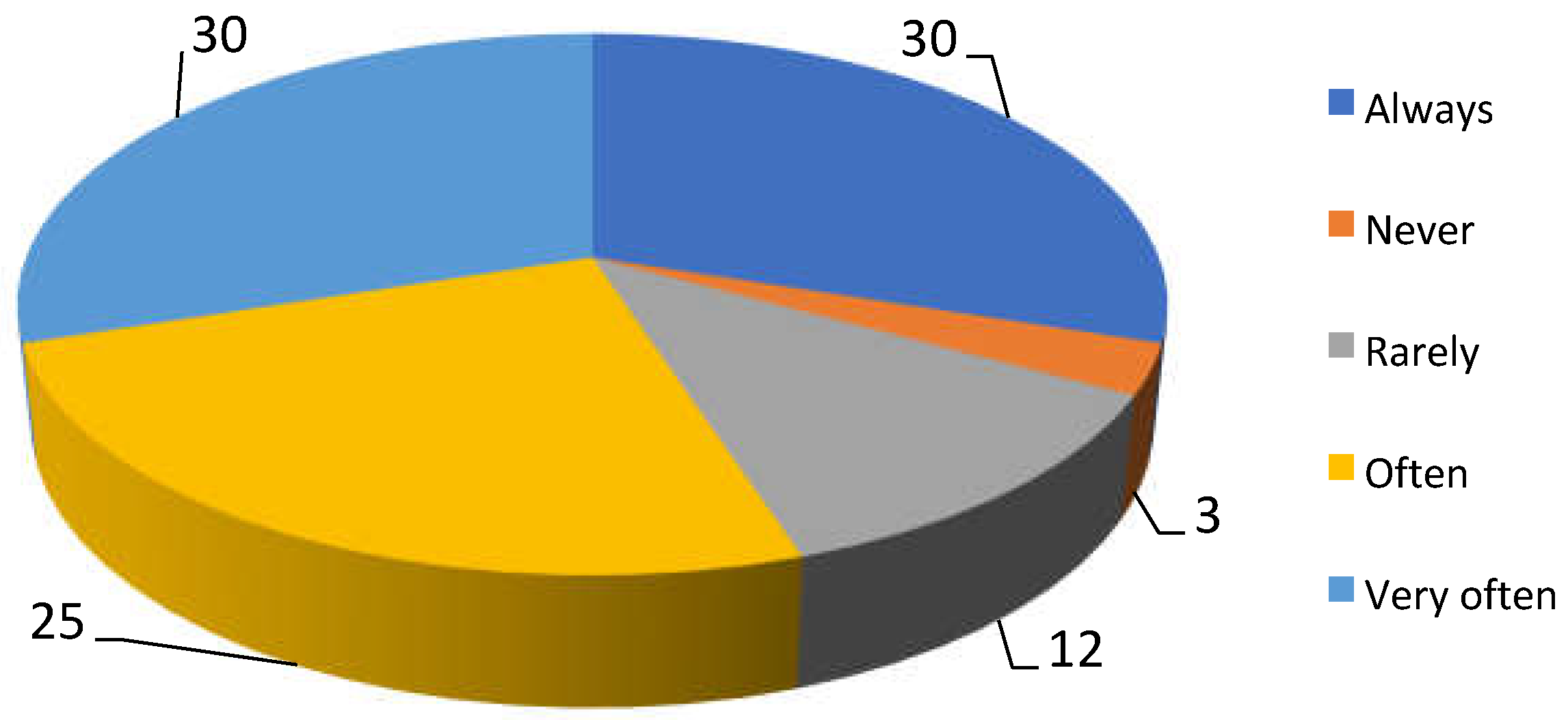

Recycling and energy saving are two relatively easy to adopt practices that can almost immediately reduce households’ environmental footprint without requiring any expensive equipment or special training. If both practices gain widespread adoption among citizens, then significant progress can be made in terms of local and national environmental quality. The adoption of such practices depends on citizens pointing to the need to dedicate more research to their current recycling and energy-saving practices. In other words, it is necessary to record the current practices of citizens in order to understand which areas require attention. Against this background, the aim of this study is to examine the profile of recyclers and non-recyclers in the city of Alexandroupolis, Greece, and to make a comparison in order to detect areas that require policy and educational interventions. Specific objectives are to identify sociodemographic differences between recyclers and non-recyclers as well as to examine and compare recycling motives, recycled materials, energy saving practices, trust in stakeholders, and the media used for their environmental information.

4. Discussion

In order to be successful, recycling and energy saving need active and continuous participation. As recycling and energy-saving behaviors are voluntary yet integral to environmental sustainability, it is essential to carry out sociological research that explores the practices, norms, and contextual factors shaping individual engagement with these behaviors. To attain a new angle, this study has compared recyclers and non-recyclers and, overall, captured an interesting differentiation, which can be used to develop new approaches to the understanding of the adoption of recycling and energy-saving practices.

The high level of recycling recorded here is in line with the high recycling percentages found in previous studies [

4,

17,

18], suggesting a wide adoption of recycling by citizens in different countries. An unexpected finding in this study was that gender and recycling frequency were independent variables, although relevant studies have shown an association with women recycling more often than men [

22,

23]. There was, however, an association between recycling frequency and age, thereby confirming the results of previous studies; much like the age ranges recorded for recyclers in the studies of Coco Chin et al. [

26] and Abushammala and Ghulam [

41], recyclers in our study were also aged between 41 and 50 years. This, however, contradicts the earlier study of McDonald and Ball [

25], who had indicated that individuals reporting higher recycling frequency were over 60 years old. On the other hand, our study found that non-recyclers are between 18 and 30 years, which comes in contrast to studies showing that recyclers can also be younger (such as Fiorillo [

22]). Education level was another influential variable, with high percentages of both recyclers and non-recyclers being university graduates. Yet, many master’s degree holders were recyclers, confirming previous studies showing that a higher educational level is positively associated with a higher recycling frequency [

4,

21]. Interestingly, marital status emerged as an important variable when it comes to recycling frequency, with married respondents reporting significantly higher recycling frequency. In our study, recyclers were mostly public employees and pensioners, whereas non-recyclers were private employees and pensioners. A similar study had shown that unemployed individuals, homemakers, pensioners, and freelancers tended to exhibit higher commitment to recycling practices [

26]. The differences between this study and ours may be attributed not only to the sample but also to the different conditions (such as the availability of recycling bins) in each study area.

Respondents’ environmental views were also examined in order to form a spherical idea of their profile. Regardless of the recycling frequency, most respondents perceived that there are significant environmental problems and that natural resources are constantly decreasing, with these findings being in line with those of Liao et al. [

30] and Zerinou et al. [

29]. They also recognized recycling and energy saving as good practices that can contribute to the mitigation of environmental problems. These findings are in line with the studies of Altikolatsi et al. [

19] and Thomas et al. [

20], indicating that the public may be becoming increasingly aware of the environmental benefits of recycling and energy saving. This may imply that public campaigns aimed at raising awareness about recycling and energy saving have been successful in the areas where these studies have been conducted.

The motives driving individuals to commit to recycling are important to examine for several reasons. Specifically, knowing what motivates people can help design policies and campaigns that effectively encourage the adoption of recycling practices [

42]. Another benefit is that such insights guide the tailoring of communication strategies; as different people are affected by different factors (environmental concern, financial rewards), understanding their motives enables targeted messaging that appeals to different groups [

43]. In addition, potential barriers can be identified and addressed, while new strategies to reinforce recycling habits can be developed [

42,

43]. In our study, environmental protection was the most important motive, confirming the previous studies of Perrin and Barton [

44] and Williams et al. [

45], whose results also indicated the strong effect of environmental concern on the adoption of recycling practices. At the same time, environmental concerns also seem to motivate individuals to adopt energy-saving practices [

4,

46]. A somewhat unexpected motive was that recyclers viewed recycling as an experience that brought them a feeling of personal fulfillment, as Liao et al. [

30] have also observed.

In order to improve recycling programs or ensure their effectiveness, it is necessary to examine the materials that citizens recycle because this can point to the citizens’ level of familiarity with recyclable and non-recyclable materials. Plastic and paper emerged as the most recycled materials for both groups; similarly, plastic and paper were the most recycled materials in previous studies [

18,

27,

45], while aluminum has been identified as a material that is recycled less often [

4,

18,

27]. An interesting difference between recyclers and non-recyclers in our study was that recyclers recycled batteries and glass more often (yet batteries were not the most recycled material for both groups). Batteries have been found to be recycled to a lower degree than other recyclable materials, also in other relevant studies [

18,

27,

47], suggesting that there may be a lack of awareness about their recyclability or a lack of infrastructure that can facilitate battery recycling. In relation to infrastructure, however, citizens in the study area can find special recycling bins for batteries in various public places and shops, as well as in most educational institutions, supermarkets, and banks. The low rate of respondents recycling batteries recorded here suggests that there may be other factors that inhibit engagement with recycling batteries, which is worthwhile to address in a future study.

The comparison between recyclers and non-recyclers captured interesting differences in terms of energy saving. Recyclers check the energy label when buying an appliance and choose class A appliances, in contrast to non-recyclers, who reported lower levels of commitment to these practices. Recyclers’ energy saving practices are consistent with those reported in the studies of Zerinou et al. [

29] and Liao et al. [

30], while non-recyclers’ are consistent with those by Jareemit and Limmeechokchai [

34]. In addition, recyclers reported using energy-efficient bulbs much like respondents in the studies of Zywiolek et al. [

32] and Fang et al. [

48]. Thus, there is evidence that recycling engagement is associated with the adoption of energy saving practices and, therefore, it may be suggested that fostering recycling adoption can create a positive ripple effect in that it may promote the adoption of energy saving practices.

In terms of thermal practices, most respondents set the thermostat at 20–22 °C during winter, which is a temperature that has also been reported in another study in the wider area [

29]. A prominent difference between recyclers and non-recyclers was that recyclers were diligent with the annual maintenance and the proper adjustment of their heating systems, while many had installed solar heaters at their house. Regardless of recycling frequency, relatively low shares of citizens had ceiling/floor fans, shading systems, and thermal insulation. This comes in contrast to the study of Zywiolek et al. [

32] where considerable shares of householders reported having thermal insulation at their house, and the study of Mtutu and Thondlhana [

4] where offices had ceiling fans.

When exploring ways to foster engagement with recycling and energy saving, it is often recommended to leverage the influence of the media. By understanding the media sources citizens use, we can improve their information by ensuring that only accurate and reliable information about recycling and energy saving reaches them. In other words, if we know which media sources people use, we can leverage these sources in order to spread accurate and action-driven messages about recycling and energy saving [

49]. In this study, respondents turned mostly to the Internet and their family and friends as their primary sources of information, confirming previous studies showing the high usage of these sources [

29,

36]. Despite their lack of expert knowledge, family and friends have been found to be profoundly influential to individuals’ environmental views and behavior [

27,

35,

46], while they are often considered the best information sources [

50].

A last point that requires discussion concerns respondents’ evaluation of different stakeholder groups based on whether they would participate in environmental actions organized by them. Scientists and environmental groups emerged as the most trusted stakeholders, whereas political parties emerged as the least trusted. This suggests that citizens in the study area are most likely to support environmental actions organized by stakeholders that are surrounded by less controversy. The lack of trust in political parties recorded here is in line with the significant decrease in trust in political parties after the global financial crisis, particularly in southern Europe [

51].

5. Conclusions

The voluntary basis on which recycling and energy saving are performed at households brings forward the need to better understand the profile of recyclers and non-recyclers and to make meaningful comparisons between them. As environmental concern was the most important motive for carrying out recycling, it may be inferred that educational approaches emphasizing the contribution of recycling to the mitigation of environmental problems are successful in fostering recycling behaviors. Our study corroborated findings from other studies that recyclers are between 41 and 50 years old, married, and likely to have attended higher education, while non-recyclers tend to fall into younger age groups and be unmarried. Future research should thus seek to detect the social and economic factors behind these trends. Both groups recycled plastic and paper, but aluminum and batteries were recycled at a significantly lower degree, thereby pointing to the areas that need to be addressed by future recycling programs in the study area. Given the toxicity of batteries, it is worthwhile in a future study to examine further citizens’ awareness about their environmental pollution hazards, while local officials need to ensure the availability of convenient collection points. As recyclers were more engaged with energy saving, it may be suggested that recycling engagement can create a positive ripple effect by fostering energy-saving practices. Both respondent groups used mostly the Internet for their information about environmental topics, emphasizing the role that the Internet can play in spreading accurate and action-driven messages about recycling and energy saving.

Finally, the results of this study must be considered in view of certain limitations. For the purposes of analysis, respondents in this study were categorized into two groups based on their self-reported frequency of recycling. The first group, referred to as “recyclers”, includes individuals who indicated that they recycle frequently, very frequently, or always. The second group, termed “non-recyclers”, consists of those who reported recycling never or rarely. While these labels are used to differentiate relative behaviors, it is important to note that the “non-recycler” group still demonstrated a substantial level of recycling activity compared to the “recycler” group. As such, the classification reflects comparative frequency rather than complete absence of recycling behavior. In addition, results represent only the citizens in the study area and are not applicable to the entire country or other areas. Also, as the study was performed with the use of a questionnaire, it is not possible to entirely exclude the possibility that there may be a discrepancy between self-reported and actual behaviors.