Abstract

In recent years, large-scale wildfires have become a serious threat to terrestrial ecosystems and people in the Chiquitania region of Bolivia. Understanding public perceptions is fundamental to designing comprehensive and effective wildfire management strategies. The objectives of the study were to learn perception on the main causes of wildfires, to understand their perceptions of the impacts of these events, and to explore the most viable solutions to preventing future wildfires in the Chiquitania region of Bolivia. We developed a 15-questions online survey and disseminated it through social media platforms, mobile messaging service groups, and at two workshops held in two locations. A total of 597 people participated in the survey with a balanced sex distribution. The participants were mainly young people aged 18–24 (45.40%) and 25–34 (21.40%), representing university students (42.6%) and professionals (42.6%). The data came from seven departments, but Santa Cruz was more strongly represented (75.9%). In addition, although only 65% considered themselves part of the general population, the data shows that 76% had personal experience of wildfires. Respondents indicated that fires were caused by human activities (95.9%), mainly due to traditional agricultural practices. The most important perceived impacts included landscape and vegetation quality, fauna habitat and ecosystem regeneration. In addition, participants have prioritized the reinforcement of patrols and surveillance, the hiring of forest firefighters and the purchase of aerial firefighting units. For prevention, the most chosen was to change policies that promote fires, changing the vision for economic development and stricter penalties. The findings can be used to formulate public policies aimed at preventing wildfires, mitigating their impacts and promoting environmental conservation.

1. Introduction

Fire is a natural phenomenon that has been an important factor in global climate and terrestrial ecosystems dynamics [1], but land management practices have changed natural fire regimes, which poses a threat because it affects biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human well-being [2]. In the Bolivian context, fire is fundamental for local communities and adapted ecosystems, but poor fire management has led to large-scale uncontrolled fires [3,4], with significant environmental, social, and economic consequences, especially in the Chiquitania region.

In recent years, wildfires in the Chiquitania region have attracted both national and international attention, mainly due to their increasing intensity and frequency [5]. The wildfires in 2019 triggered degradation over nearly 4 million hectares [6] and highlighted the urgent need to understand the causes of this phenomenon and formulate viable solutions to mitigate its impact [7]. A number of studies have identified key factors that contribute to the occurrence of wildfires, including agricultural activities, land use changes, and traditional cultural practices [8]. However, there is still a knowledge gap in the general public’s perception of this problem and in the solutions they consider most appropriate for better fire management.

The implementation of fire management and environmental conservation policies has been hampered by several factors, including a lack of inter-institutional coordination, limited resources, and conflicts of interest between key stakeholders [9]. This situation emphasizes the need for contextualized information that can facilitate the design of more effective and equitable interventions [10]. It is essential to adopt an approach based on local perceptions and discussions to ensure that fire management strategies and public policies are aligned with cultural contexts, gain acceptance within society, and achieve environmental efficiency [11]. Furthermore, understanding these perceptions can facilitate the identification of potential barriers to the implementation of prevention and control measures and strengthen community participation in risk management of wildfires [12]. A wide range of studies indicate that perception of wildfires varies considerably between different social groups and regions, influenced by factors such as education level, direct experience with fires, and predominant economic activities [13,14,15]. However, most of these studies are based on the perception of wildfire experts [11,14,16,17,18], but little is known about the opinion of non-experts [19,20,21].

The objectives of this study were (1) to learn the perception on the main causes of wildfires, (2) to understand their perceptions of the impact of these events, and (3) to investigate the most viable solutions for preventing future wildfires in the Chiquitania region of Bolivia. The findings can be used to formulate public policies aimed at preventing wildfires, mitigating their impacts and promoting environmental conservation.

2. Study Area

The study area covers the Chiquitania region, which is an extensive undulating plain located in the department of Santa Cruz, Bolivia. The topography of the region is characterized by scattered hills formed by transverse faults and water erosion [22]. This region is home to the Chiquitano Dry Forest, one of the largest and best-preserved tropical dry forests in the Americas [23]. This forest intersects with different scattered formations of rocky outcrops, shrublands, wetlands, and savannas [24].

Historically, Chiquitania has been inhabited by a diverse group of indigenous peoples (Chiquitano, Guarayo, Guarasugwe, and Ayoreo). However, the region is also home to a diverse population of Creoles, indigenous groups from western Bolivia and Mennonite colonies [22,25]. In relation to the estimated population of inhabitants in Bolivia until 2021 (11.8 million), it is estimated that 23% was concentrated in municipalities in the Chiquitania region [26]. The city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, located in the Chiquitano Dry Forest, has the highest population density and diversity of people of the country’s nine departments [26]. Furthermore, fire has traditionally been used in this region, as is the case with slash-and-burn practices (Figure 1). However, poor fire management and other causes have led to large-scale wildfires [4].

Figure 1.

Slash-and-burn practices in the Chiquitano Dry Forest. Photo: Claudia Belaunde/FCBC.

3. Methods

3.1. Survey Structure and Participant Selection Criteria

We designed a survey with questions to understand the perceptions of experts and non-experts about wildfires in the Chiquitania region, so that criteria for selecting responses focused on a diverse group. The wording and selection of questions was based on the previous experience of authors working with surveys in Bolivia, as well as other experiences and expert opinions obtained in other countries [11]. Participants were required to have a device (computer or cell phone), Internet connection, and the willingness to dedicate time to complete the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria included employees of the Foundation for the Conservation of the Chiquitano Forest (FCBC), and the co-authors of this article were instructed not to respond to the survey for bias not to affect the results. Furthermore, people who were not born in Bolivia were not allowed to participate in the study. Due to the limitations of the COVID-19 health crisis, the survey was conducted online.

The survey was developed using Google Forms application and consisted of 15 questions divided into four sections: (i) socio-demographic characteristics, (ii) causes of wildfires, (iii) impacts of wildfires, and (iv) possible actions to extinguish or prevent wildfires. In the socio-demographic components, participants had to choose a single answer for sex, age, Bolivia origin, educational level, self-identified group (wildfire experts and non-experts), and the number of fires they experienced. In the section on the causes of wildfires, they had to choose from one to multiple answers on the main origins and causes of the different human activities. In the section on wildfire impacts, questions with one or multiple selections and a matrix (lowest to highest) were included to allow participants to identify impacts on infrastructure, wildlife group, forest regeneration, and vegetation type. In the actions section, multiple answers were included to identify potential activities to suppress or prevent wildfires (Table A1, see Supplementary Materials). The instrument used simple language, which minimized the possibility of misinterpretation of the questions. Survey questions were provided in Spanish.

Since many people in rural areas did not have email addresses, the form was configured so that everyone could respond. Participants accessed the form via direct link and upon entering found the contents of the informed consent form, which they had to accept before continuing the survey. The consent form emphasized that participation was anonymous and voluntary. Before applying the instrument, we conducted pilot tests, not included in this study, to test its reliability in academic terms.

3.2. Dissemination of the Survey

Between 16 and 17 June 2021, we sent out the survey via on social media platforms and mobile messaging service groups, and it remained open until 31 July. The announcement about the study and the survey was published on a social network (Facebook) of the FCBC, which up to that moment had a total of approximately 9000 followers from different regions of Bolivia and other countries. In addition, the survey was disseminated in five groups of users of the mobile messaging service (WhatsApp) in which around 400 people participated, both students and professors of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences of the Gabriel René Moreno Autonomous University (city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra), as well as in FCBC coordination groups with local actors of the Chiquitania region. Different users were suggested to forward the survey to other people, so it was not possible to count the total number of people who received the messages, regardless of whether they responded to the surveys. In addition, between 22 and 23 July, during two training workshops held in two localities of the Chiquitania (San José de Chiquitos and Roboré), we distributed the survey online to 36 participants, including park rangers, water cooperative technicians, representatives of municipalities, peasant communities, indigenous territories, and civil society.

3.3. Data Processing and Analysis

The data obtained from the online form were processed using software such as Microsoft Excel and Python. Data processing was started by cleaning the data and ensuring that the data used were complete and none were missing. Because the data obtained for each variable were nominal and ordinal categorical data, normality tests were not performed. To address the limitations associated with the sample size and to improve the robustness of the statistical analyses, bootstrap techniques were employed. In this study, 10,000 bootstrap samples were generated from the original data set, and each sample was drawn randomly with replacement. The frequencies and percentages of each sample were recalculated and then the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles were obtained for the 95% confidence intervals for each category (95%IC). This approach improved the reliability and interpretability of the results. Chi-square tests (χ2) were used to compare categorical variables, identifying significant associations between sociodemographic characteristics and responses for cause, impact, and action variables.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

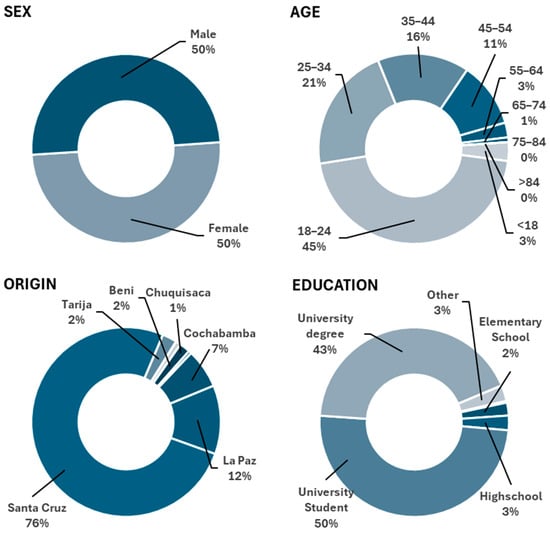

A total of 597 people participated in the survey with a balanced sex distribution, with 50.10% (95%IC: 45.7–54.5) identifying as women and 49.90% (95%IC: 45.5–54.3) as men (see Figure 2, Table A2). With respect to age, the majority of respondents were aged 18 to 24 years (45.40%, 95%IC: 41.5–49.3), followed by 25 to 34 (21.40%, 95%IC: 18.3–24.9), indicating a predominantly young population (see Figure 2, Table A2). Geographically, the majority of responses originated from the department of Santa Cruz (75.88%, 95%IC: 73.48–78.22), and the remaining 24.12% were distributed in other six departments (Figure 2, Table A2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of survey participants by sex, age, department of origin, education level, self-identified group, experience with number of wildfire events.

The largest number of participants were either current university students (49.70%, 95%IC: 45.8–53.6) or university graduates (42.60%, 95%IC: 38.6–46.4), reflecting a highly educated sample (Figure 2, Table A2). Furthermore, 65.0% of the participants (95%IC: 61.1–68.8) identified themselves as part of the general population, while the rest (35.0%) were directly affected, wildfire experts, and decision-makers (Figure 2, Table A2). However, almost 75.90% indicated that they experienced between 1 and more than 10 wildfires, highlighting the wide exposure to wildfires among the surveyed population (Figure 2, Table A2).

The results evidenced statistically significant associations between people with previous wildfire experience and the categories of men (χ2 = 14.2, p = 0.012), originating from the department of Santa Cruz (χ2 = 6.8, p = 0.043), and with a high level of education (χ2 = 18.3, p = 0.021). In addition, there were significant associations between people who self-identified as wildfire experts and those of older age (χ2 = 0.5, p = 0.008) and with a high level of education (χ2 = 2.7, p < 0.001).

4.2. Causes of Wildfires

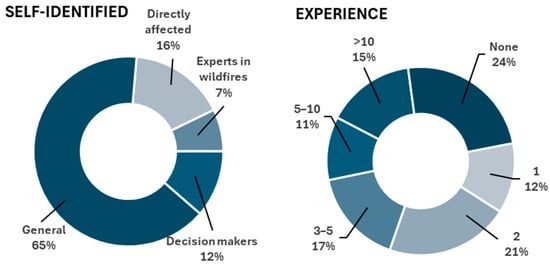

The majority of respondents (95.9%, 95%IC: 94.2–97.4) identified human-induced factors as the primary cause of wildfires in the Chiquitano region (Figure 3, Table A3). In addition, volunteers indicated that the origin of these fires is mainly related to traditional agricultural practices (22.5%, 95%IC: 20.4–24.6), actions of a social groups with political interests (17.6%, 95%IC: 15.8–19.5), negligence of citizens (16.2%, 95%IC: 14.4–18.1), and actions of a social group with interests in land trafficking (14.9%, 95%IC: 13.2–16.7). These results emphasize the complex interaction of economic, cultural, and political factors behind wildfires in the region.

Figure 3.

Proportion of responses on the main causes of the origins of wildfires and different human actions.

Regarding the significant associations of the variables, men identified that the main causes of wildfires were due to traditional agricultural practices (χ2 = 15.82, p = 0.018), while women attributed wildfires to citizen negligence (χ2 = 12, p = 0.024). In terms of education level, university students related wildfires to mechanized agriculture for commercial purposes (χ2 = 28.94, p = 0.004) and professionals reported more wildfires associated with illegal hunters (χ2 = 4.32, p = 0.038). In addition, wildfire experts prioritized causes related to land trafficking (χ2 = 4.76, p = 0.009) and decision-makers related it to pasture and livestock management in cattle ranching (χ2 = 6.57, p = 0.010).

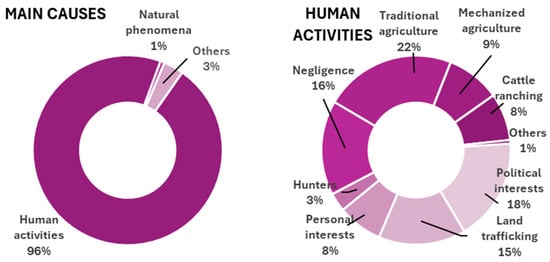

4.3. Impacts of Wildfires

The survey revealed that respondents identified landscape and vegetation quality (30.8%, 95%IC: 28.5–33.2), wildlife habitat (29.1%, 95%IC: 26.8–31.5), and regeneration ecosystems (21.5%, 95%IC: 19.4–23.7) as the categories most affected by wildfires (Figure 4, Table A4). Among animal species, mammals (26.7%, 95%IC: 24.5–28.7), reptiles (25.3%, 95%IC: 23.1–27.5), and birds (17.9%, 95%IC: 15.8–19.9) were identified as the most affected groups (Figure 4, Table A4). In terms of infrastructure damage or destruction, volunteers indicated that agricultural or livestock infrastructure (25.42%, 95%IC: 23.8–27.1), houses (18.7%) and water supply networks (13.27%, 95%IC: 11.8–14.8) were the most affected (Figure 4, Table A4). Regarding the regeneration of burned forest areas, 40.3% (95%IC: 37.1–43.7) of respondents believe that forests will recover within 25 years (Figure 4, Table A4). These findings highlight the broad ecological and infrastructural impacts of wildfire events across diverse systems.

Figure 4.

Proportion of responses on the main impacts of wildfires, infrastructure, wildlife, and regeneration processes.

The results show a significant association of women mentioning the main impact on wildlife habitat (χ2 = 6.42, p = 0.011), while men more frequently mention decreased economic income (χ2 = 4.89, p = 0.027). In addition, decision-makers prioritize impacts on regenerating ecosystems (χ2 = 30.12, p = 0.001). In terms of age, the young group emphasize human losses or damage (χ2 = 24.89, p = 0.003). In terms of impact on wildlife groups, wildfire experts most frequently mention reptiles and birds (χ2 = 18.73, p = 0.015). In the infrastructure categories, men most frequently associate wildfire impact with damage to agricultural or livestock infrastructure (χ2 = 5.76, p = 0.016), while women indicate water supply networks (χ2 = 12.56, p = 0.028).

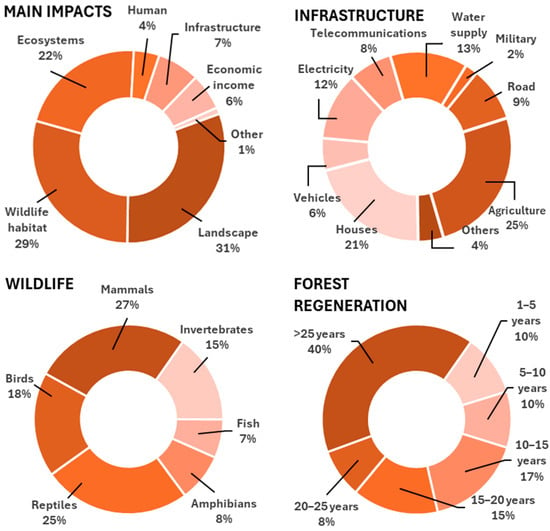

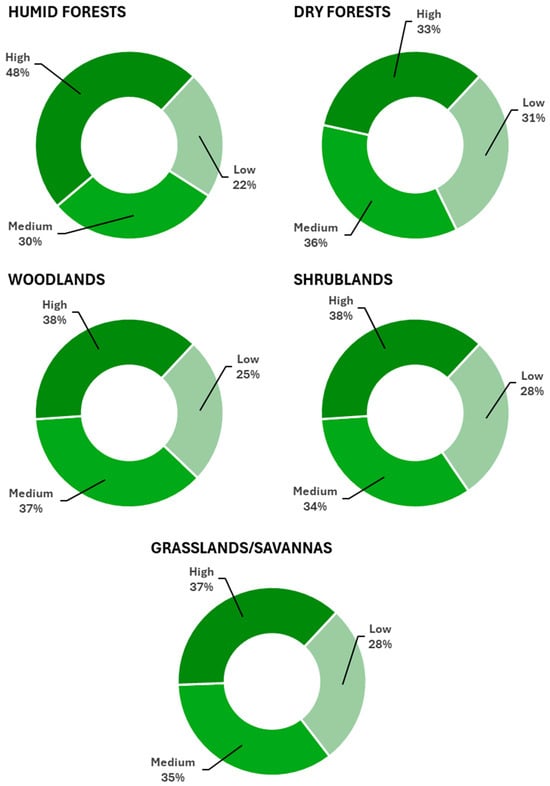

According to vegetation types, volunteers selected degrees of impact (low, medium and high) for five different ecosystem types. Respondents identified the highest degree of impact in humid forests with 48.1% (95%IC: 44.0–52.2), followed by woodlands (38.0%, 95%IC: 35.3–40.7), shrublands (38%, 95%IC: 35.8–40.3), grasslands/savannahs (37.5%, 95%IC: 34.5–40.6), and dry forests (33.5%, 95%IC: 29.9–37.2) (Figure 5, Table A4). These perceptions suggest a widespread awareness of significant pressures on ecosystems, particularly on forests.

Figure 5.

Proportion of responses of wildfire impact levels in humid forests, dry forests, wooded forests, shrublands, grasslands, and savannahs.

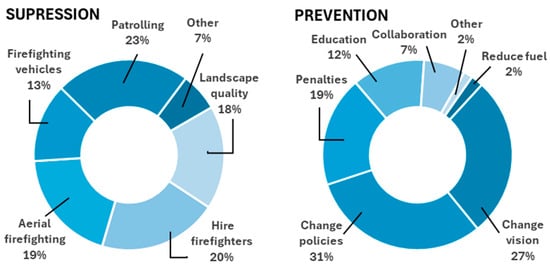

4.4. Actions to Suppress and Prevent Wildfires

Regarding wildfire suppression actions, Bolivians predominantly prioritized improving patrolling and surveillance, which accounted for 22.8% of responses (95%IC: 20.6–24.2), followed by hiring forest firefighters (20.6%, IC95%: 18.3–21.7) and purchasing aerial firefighting units (19.4%, 95%IC: 17.4–20.6) (Figure 6, Table A5). These perceptions emphasize the need to highlight the importance of early detection and rapid response to wildfire outbreaks. For prevention, the most chosen was to change policies that promote fires (30.8%, 95%IC: 29.6–32.0), followed by changing the vision for economic development (27.3%, 95%IC: 26.1–28.5) and stricter penalties (18.8%, 95%IC: 17.8–19.8) (Figure 6, Table A5).

Figure 6.

Proportion of responses for wildfire suppression and prevention actions.

Regarding extinguishing actions, there was a significant association with men proposing to hire forest firefighters (χ2 = 6.82, p = 0.009). In addition, decision-makers were more associated with proposing the purchase of aerial firefighting units (χ2 = 8.97, p = 0.003), while university students frequently mentioned the improvement of patrols/surveillance (χ2 = 5.23, p = 0.022). In relation to prevention actions, men showed a higher frequency of stricter sanctions for those who set wildfires (χ2 = 4.82, p = 0.028). Professionals and university students proposed changing policies that promote wildfires (χ2 = 9.15, p = 0.002) and students of secondary education or lower prioritized improving the education and knowledge of Individuals and communities (χ2 = 7.34, p = 0.007). In addition, decision-makers and wildfire experts significantly associated the action of changing the vision of economic development (χ2 = 12.73, p < 0.001), while the general population and people directly affected highlighted improving collaboration between institutions (χ2 = 6.95, p = 0.008).

5. Discussion

5.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

The results show that socio-demographically, the highest percentage of respondents were originally from the department of Santa Cruz, where the Chiquitania region is geographically located, although people originating or residing in other departments also responded. The size of the sample obtained in this study (n = 597) was low in relation to the number of inhabitants in Bolivia or the Chiquitana region, and this could be considered statistically unrepresentative. A possible explanation for this low participation may be due to the lack of interest of other inhabitants of the country to respond on a topic, issue, or region they do not know about. Further studies are needed to better understand this type of behavior. The largest proportion of the age group was represented by young people with a university or professional education, most likely a result of the media through which the surveys were disseminated. In addition, although only 7% of the respondents considered themselves wildfire experts, the data show that 76% personally experienced at least one fire event, so it was not a totally unfamiliar topic. However, it has been suggested that people who have suffered a wildfire experience do not necessarily have a higher perception of the risk of these events [27], so our results should be handled with caution.

5.2. Causes of Wildfires

In the Chiquitania region, wildfires have been mainly attributed to human activities [28], which coincides with the perceptions of the respondents to this study. Although some fires have been reported as lightning-induced events [29], this phenomenon remains largely unknown to the public. The respondents also emphasized that wildfires arise particularly from agricultural practices, actions of a social groups with political interests, negligence of citizens, and actions of a social group with interests in land trafficking. While these perceptions seem valid and are reflected in the mediatic discourse, no official study has yet confirmed the causes, whether natural or human. It is crucial to conduct specialized wildfire investigations led by experts from state agencies which incorporate evidence collected directly from the field. In this study, questions related to climate change were not included. It is known that some climatic phenomena, such as meteorological droughts, have been one of the main drivers for the spread of fires in combination with other factors in the Chiquitana region [30]. Future surveys should include questions related to climate, including some potential responses such as increased temperatures, heat waves, and frost.

5.3. Impacts of Wildfires

In general, society perceives fire as a natural risk with negative implications [31]. However, research on the impact of wildfires in Bolivia has been limited to specific topics, and no comprehensive study of social, environmental, and ecological information has been conducted yet. Social and economic impact data are scarce due to the limited availability of information, focusing mainly on the number of affected families or production systems [32,33]. On the other hand, ecological studies are more comprehensive and evaluate impacts on landscapes, ecosystems, and species [34,35,36]. Most respondents recognized that the greatest impact of wildfires is related to landscape and vegetation quality, wildlife habitat, and regeneration ecosystems. Moreover, agricultural and livestock infrastructures, housing, and the water supply network were identified as the most affected in terms of damage or destruction. In general, few people recognized the economic consequences, human losses, or destruction of infrastructure [32]. This observation highlights a critical point, namely that for many, the interdependence of production systems and natural systems is not yet clear. It is crucial to highlight in future public discourse that wildfires not only cause fundamental damage to ecosystems, but also significantly affect production systems and livelihoods, in many cases of particularly vulnerable indigenous communities that depend on the functioning of ecosystems and their interim services. In terms of regeneration processes, more than half of the respondents believe that forests need less than 25 years to return to a state that could be considered original. However, it is not yet clear how many years are needed for complete regeneration of forest, especially considering the presence of trees that can reach an age of more than 150 years [37]. At the landscape level, regeneration patterns have shown growing and decreasing trends [38]. In contrast to the answers of the respondents, field-based studies indicate that some ecosystems, especially dry forests, show high regeneration capacity after wildfires [39], with higher tree survival rates [40]. These findings on the impact of wildfire are crucial and must be taken into account in the development of communication and regeneration strategies. Understanding the multi-faceted consequences can promote better integration of ecological and socio-economic systems, which ultimately leads to more effective decision-making and resilience-building efforts.

5.4. Actions to Suppress and Prevent Wildfires

Fire management strategies require a combination of fire suppression and prevention measures, but financial constraints often limit the implementation of these strategies [41]. The results of the survey indicate a focus on strengthening patrolling and surveillance as the most critical action for reducing wildfire, in addition to hiring forest firefighters and purchasing aerial firefighting units, highlighting the importance of early detection and rapid response. In terms of prevention, the preference for changing policies that promote fires, changing the vision for economic development and stricter penalties, highlights the recognition of gaps in public regulations and the inadequate enforcement of existing regulations, which exacerbate occurrences the occurrence of wildfires. Collectively, these findings suggest that a multifaceted approach—including stronger action and stronger regulatory frameworks—is essential to effective wildfires management in the Chiquitania region. By addressing these identified priorities, policymakers could develop comprehensive strategies that not only suppress wildfires, but also prevent their occurrence, thus fostering sustainable development and resilience in this ecologically vulnerable region.

5.5. Final Considerations

The effectiveness of sending surveys through messaging groups or social networks is not entirely clear, so this is an issue that needs to be addressed. Future surveys should be targeted to specific key stakeholders with personalized support. In this sense, there is a need to design data collection tools that are more accessible and engaging, thus ensuring greater public participation and a deeper understanding of general perceptions about wildfires, especially in rural areas where Internet connectivity is low or non-existent [42].

This study did not address potential biases such as social desirability or knowledge limitations. In terms of social desirability, it is possible that some respondents might blame external actors rather than admit any personal responsibility. In the case of knowledge limitations, respondents were a diverse group of people with different levels of education and may not know about ecosystem impact assessments, differences between ecosystem types, or the years it takes for the forest to regenerate. These aspects are important to be considered in future studies.

The results helped to identify information gaps on various aspects of wildfires, including their causes, impact, and the necessary measures for their management. For instance, although there is a spread of data on biodiversity loss, ecosystem effects, and socio-economic impacts, this information has not been systematically aggregated to comprehensively address the research questions. Lack of detailed studies on the underlying causes of wildfires and their relationship to human practices and climate change impedes the development of effective policies for prevention and mitigation policies. Consequently, existing data can be used a basis for further refinement of communication strategies by adopting a development-oriented approach. It is imperative to evaluate existing information to formulate messages that explain the interconnections between natural and productive systems, underlining the multifaceted impacts of wildfires on ecosystems, the economy, and social well-being. A more systemic and action-oriented approach will promote greater public involvement in the prevention and management of wildfires, contributing to sustainable development in regions affected such as the Chiquitania.

6. Conclusions

This study explored the perception of the effects of wildfires in Bolivia, focusing on the Chiquitania region. It emphasized the importance of human causes of wildfires in relation to economic, cultural, and political factors. The respondents identified important impacts on the ecosystems and infrastructure such as habitat destruction and ecosystem regeneration. However, it was found that there is limited knowledge of the socio-economic consequences of wildfires, highlighting the need for effective education and policy reforms. The study found that the priorities for dealing with wildfires are to improve surveillance, land management, and fire suppression. In addition, a lack of data on the causes and long-term effects of wildfires was revealed, indicating the need for more research and evidence-based strategies. The integration of ecological and socio-economic perceptions is essential to the development of strategies that not only suppress wildfires, but also prevent their occurrence and promote resilience and sustainable development in affected areas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/earth6020032/s1, Complementary materials. English version of the form used to obtain the perceptions of the wildfires in the Chiquitania region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M. and P.H.; Data curation, O.M.; Formal analysis, O.M.; Investigation, O.M.; Methodology, O.M., P.H., N.M. and C.V.; Validation, O.M.; Visualization, O.M.; Writing—original draft, O.M.; Writing—review and editing, O.M., P.H., N.M. and C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have not received specific funding for this work. The surveys conducted in the workshops were carried out during the ECCOS (Ecorregiones Conectadas Conservadas Sostenibles) project funded by the European Union, and the Knowledge Bases for Restoration project funded by the Government of Canada and coordinated by the Foundation for the Conservation of the Chiquitano Forest (FCBC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data use had consent and approval of the ethics committee of the FCBC and did not contradict the guidelines of Bolivian legislation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study will be available on request from the corresponding author on a case-by-case basis.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the people who submitted information to the survey forms. We also thank Eunice Copa and Carla Pinto for their help in coordinating the dissemination of the surveys. Roberto Vides and Palaiologou Palaiologos reviewed and commented on the content of the survey form. To Rosa Leny Cuellar, Roger Coronado, Claudia Belaunde, and Sixto Angulo for their valuable help in the organization of the workshops. We thank the two reviewers for their insightful comments that significantly strengthened the quality of our paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questions by section and types of responses included in the survey.

Table A1.

Questions by section and types of responses included in the survey.

| Survey Questions | Sections | Types of Responses |

|---|---|---|

| 1. In which department of Bolivia do you live? | Socio-demographic characteristics | Drill Down: one answer |

| 2. In your opinion, what is the main cause of wildfires in the Chiquitania? | Causes of wildfires | Multiple Choice: one answer |

| 3. If you previously answered that they are caused by human activities, which of these practices do you think are the main causes of wildfires in Chiquitania? | Causes of wildfires | Multiple Choice: multiple answer |

| 4. In which areas do you think the wildfires in Chiquitania had the greatest impact? | Impacts of wildfires | Multiple Choice: multiple answer |

| 5. In your opinion, what is the degree of impact of wildfires on ecosystems in the Chiquitania? | Impacts of wildfires | Matrix: lowest to highest |

| 6. How long do you think it takes for forests to regenerate after the wildfires in Chiquitania? | Impacts of wildfires | Multiple Choice: one answer |

| 7. In your opinion, which groups of wildlife were most affected during the wildfires in Chiquitania? | Impacts of wildfires | Multiple Choice: multiple answer |

| 8. What are the main types of damage or destruction to infrastructure that can occur during a wildfire in the Chiquitania? | Impacts of wildfires | Multiple Choice: multiple answer |

| 9. What actions do you think are the most effective for extinguishing wildfires in Chiquitania? | Possible actions | Multiple Choice: multiple answer |

| 10. What actions do you think are the most effective to prevent wildfires in Chiquitania? | Possible actions | Multiple Choice: multiple answer |

| 11. Which group of people do you identify with? | Socio-demographic characteristics | Multiple Choice: one answer |

| 12. How many wildfires have you personally experienced, in or near an affected area in the Chiquitania region, in the last two years? | Socio-demographic characteristics | Multiple Choice: one answer |

| 13. Age of the interviewee | Socio-demographic characteristics | Multiple Choice: one answer |

| 14. Education level | Socio-demographic characteristics | Multiple Choice: one answer |

| 15. Sex | Socio-demographic characteristics | Multiple Choice: one answer |

Table A2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents with statistical metrics.

Table A2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents with statistical metrics.

| Atributes | Category | Frecuency | % | 95%IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 299 | 50.10 | 45.7–54.5 |

| Male | 298 | 49.90 | 45.5–54.3 | |

| Age | <18 | 19 | 3.20 | 2.0–4.7 |

| 18–24 | 271 | 45.40 | 41.5–49.3 | |

| 25–34 | 128 | 21.40 | 18.3–24.9 | |

| 35–44 | 93 | 15.60 | 12.9–18.6 | |

| 45–54 | 66 | 11.10 | 8.7– 13.8 | |

| 55–64 | 15 | 2.50 | 1.4–4.0 | |

| 65–74 | 5 | 0.80 | 0.3–1.7 | |

| 75–84 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0–0.0 | |

| >84 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0–0.0 | |

| Origin in Bolivia | Beni | 11 | 1.84 | 0.82–3.28 |

| Chuquisaca | 3 | 0.50 | 0.00–1.17 | |

| Cochabamba | 40 | 6.70 | 4.82–8.76 | |

| La Paz | 70 | 11.73 | 9.53–14.02 | |

| Santa Cruz | 453 | 75.88 | 73.48–78.22 | |

| Tarija | 15 | 2.51 | 1.34–4.19 | |

| Oruro | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | |

| Pando | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | |

| Potosí | 5 | 0.84 | 0.17–1.84 | |

| Education Level | Without School | 2 | 0.30 | 0.0–1.1 |

| Elementary school | 13 | 2.20 | 1.2–3.6 | |

| Highschool | 15 | 2.50 | 1.5–4.1 | |

| University Student | 297 | 49.70 | 45.8–53.6 | |

| Professional with university degree (Bachelor, Master, PhD) | 254 | 42.60 | 38.6–46.4 | |

| Others | 16 | 2.70 | 1.6–4.3 | |

| Self-identified group | People directly affected by wildfires | 98 | 16.40 | 13.6–19.5 |

| Experts in wildfires | 43 | 7.20 | 5.3–9.6 | |

| Decision-makers | 68 | 11.40 | 9.0–14.2 | |

| Population in general | 388 | 65.00 | 61.1–68.8 | |

| Wildfires experienced | 1 | 72 | 12.10 | 9.6–14.9 |

| 2 | 127 | 21.30 | 18.3–24.6 | |

| 3–5 | 98 | 16.40 | 13.6–19.6 | |

| 5–10 | 65 | 10.90 | 8.5–13.7 | |

| >10 | 91 | 15.20 | 12.5–18.3 | |

| None | 144 | 24.10 | 21.0–27.5 |

Table A3.

Main causes of wildfires selected by respondents with statistical metrics.

Table A3.

Main causes of wildfires selected by respondents with statistical metrics.

| Atributes | Category | Frecuency | % | 95%IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main causes | Human activities (e.g., logging, negligence) | 585 | 95.9 | 94.2–97.4 |

| Natural phenomena (e.g., lightning storms) | 4 | 0.7 | 0.2–1.5 | |

| Others | 21 | 3.4 | 2.1–5.1 | |

| Causes by human activities | Actions of a social group with political interests | 340 | 17.6 | 15.8–19.5 |

| Actions of a social group with interests in land trafficking | 287 | 14.9 | 13.2–16.7 | |

| Actions by individuals with personal interests | 148 | 7.7 | 6.4–9.1 | |

| Illegal hunters | 62 | 3.2 | 2.4–4.2 | |

| Negligence of citizens (e.g., lit cigarettes, bonfires) | 312 | 16.2 | 14.4–18.1 | |

| Traditional agricultural practices (chaqueos) | 432 | 22.5 | 20.4–24.6 | |

| Mechanized agriculture for commercial purposes | 178 | 9.2 | 7.8–10.8 | |

| Pasture and livestock management in cattle ranching | 156 | 8.1 | 6.7–9.6 | |

| Others | 12 | 0.6 | 0.2–1.0 |

Table A4.

Main impact of wildfires selected by respondents with statistical metrics.

Table A4.

Main impact of wildfires selected by respondents with statistical metrics.

| Atributes | Category | Frecuency | % | 95%IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main impacts | Landscape and vegetation quality (e.g., air quality, forest types) | 412 | 30.8 | 28.5–33.2 |

| Wildlife habitat (e.g., birds, fishes) | 389 | 29.1 | 26.8–31.5 | |

| Ecosystems that were regenerating (e.g., previously burned forests) | 287 | 21.5 | 19.4–23.7 | |

| Human loss or damage (e.g., injuries, fatalities) | 57 | 4.3 | 3.1–5.7 | |

| Destruction and damage to infrastructure (e.g., houses, water supply network) | 95 | 7.1 | 5.7–8.8 | |

| Decrease in economic income (e.g., income from agricultural production) | 82 | 6.1 | 4.7–7.8 | |

| Others | 15 | 1.1 | 0.5–1.9 | |

| Degree of impact on humid forests | Low | 132 | 22.1 | 18.9–25.6 |

| Medium | 178 | 29.8 | 26.3–33.5 | |

| High | 287 | 48.1 | 44.0–52.2 | |

| Degree of impact on dry forests | Low | 184 | 30.8 | 27.4–34.5 |

| Medium | 213 | 35.7 | 32.1–39.3 | |

| High | 200 | 33.5 | 29.9–37.2 | |

| Degree of impact on woodlands | Low | 150 | 25.1 | 22.5–27.8 |

| Medium | 220 | 36.9 | 34.1–39.6 | |

| High | 227 | 38.0 | 35.3–40.7 | |

| Degree of impact on shrublands | Low | 170 | 28.5 | 25.8–31.2 |

| Medium | 200 | 33.5 | 30.5–36.5 | |

| High | 227 | 38.0 | 35.8–40.3 | |

| Degree of impact on grasslands/savanna | Low | 165 | 27.6 | 24.7–30.6 |

| Medium | 208 | 34.8 | 31.8–37.9 | |

| High | 224 | 37.5 | 34.5–40.6 | |

| Years of forest regeneration | 1–5 | 62 | 10.5 | 8.3–12.9 |

| 5–10 | 57 | 9.6 | 7.5–12.1 | |

| 10–15 | 98 | 16.6 | 14.0–19.4 | |

| 15–20 | 87 | 14.7 | 12.2–17.4 | |

| 20–25 | 49 | 8.3 | 6.3–10.6 | |

| >25 | 239 | 40.3 | 37.1–43.7 | |

| Wildlife groups | Insects and other invertebrates | 167 | 15.3 | 13.5–17.2 |

| Fishes | 72 | 6.6 | 5.2–8.2 | |

| Amphibians (frogs and toads) | 89 | 8.2 | 6.6–9.9 | |

| Reptiles (e.g., lizards, snakes, turtles) | 275 | 25.3 | 23.1–27.5 | |

| Birds | 194 | 17.9 | 15.8–19.9 | |

| Mammals | 289 | 26.7 | 24.5–28.7 | |

| Major infrastructure damage or destruction | Houses | 395 | 21.23 | 19.5–23.0 |

| Private vehicles, machinery and mechanical equipment | 102 | 5.48 | 4.5–6.5 | |

| Electricity network | 216 | 11.61 | 10.3–12.9 | |

| Telecommunications network | 138 | 7.42 | 6.3–8.6 | |

| Water supply network | 247 | 13.27 | 11.8–14.8 | |

| Military equipment and facilities | 39 | 2.1 | 1.5–2.7 | |

| Road network and public transportation | 172 | 9.24 | 8.0–10.5 | |

| Agricultural or livestock infrastructure | 473 | 25.42 | 23.8–27.1 | |

| Others | 79 | 4.24 | 3.4–5.1 |

Table A5.

Main wildfire prevention and suppression actions proposed by respondents with statistical metrics.

Table A5.

Main wildfire prevention and suppression actions proposed by respondents with statistical metrics.

| Atributes | Category | Frecuency | % | 95%IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actions for fire suppression | Landscape and vegetation quality maintanance (e.g., air quality, forest types) | 241 | 17.6 | 15.7–18.9 |

| Hire forest firefighters | 278 | 20.3 | 18.3–21.7 | |

| Purchase aerial firefighting units | 265 | 19.4 | 17.4–20.6 | |

| Purchase new firefighting vehicles | 184 | 13.4 | 11.8–14.6 | |

| Improve patrolling/surveillance | 312 | 22.8 | 20.6–24.2 | |

| Others | 89 | 6.5 | 5.3–7.5 | |

| Actions to prevent fires | Reduce forest fuel | 48 | 2.1 | 1.7–2.5 |

| Change economic development vision | 623 | 27.3 | 26.1–28.5 | |

| Change policies that promote fires | 702 | 30.8 | 29.6–32.0 | |

| Implement stricter penalties for fire setters | 429 | 18.8 | 17.8–19.8 | |

| Improve education and awareness for individuals and communities | 283 | 12.4 | 11.5–13.3 | |

| Improve collaboration between institutions that prevent and control fires | 162 | 7.1 | 6.4–7.8 | |

| Others | 34 | 1.5 | 1.1–1.9 |

References

- Kelly, K.M.; Giljohann, A.; Duane, N.; Aquilué, S.; Archibald, E.; Batllori, A.F.; Bennett, S.T.; Buckland, Q.; Canelles, M.F.; Clarke, M.-J.; et al. Fire and biodiversity in the Anthropocene. Science 2020, 370, eabb0355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Kolden, C.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Johnston, F.H.; Van Der Werf, G.R.; Flannigan, M. Vegetation fires in the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devisscher, T.; Anderson, L.O.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Galván, L.; Malhi, Y. Increased wildfire risk driven by climate and development interactions in the Bolivian Chiquitania, Southern Amazonia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, I.; Inturias, M.; Masay, E.; Peña, A. Decolonizing Wildfire Risk Management: Indigenous Responses to Fire Criminalization Policies and Increasingly Flammable Forest Landscapes in Lomerío, Bolivia. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 147, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Muñoz, A.; Jansen, M.; Nuñez, A.M.; Toledo, M.; Vides, R.A.; Kuemmerle, T. Fires scorching Bolivia’s Chiquitano forest. Science 2019, 366, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anívarro, R.; Azurduy, H.; Maillard, O.; Markos, A. Diagnóstico por Teledetección de Áreas Quemadas en la Chiquitania. In Informe Técnico del Observatorio Bosque Seco Chiquitano; Fundación para la Conservación del Bosque Chiquitano: Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, 2019; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- TIERRA. Fuego en Santa Cruz. Balance de los Incendios Forestales 2019 y su Relación con la Tenencia de la Tierra; Fundación TIERRA: La Paz, Bolivia, 2019; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, J.; Kennard, D.; Fuentes, A. Smokey the Tapir: Traditional Fire Knowledge and Fire Prevention Campaigns in Lowland Bolivia. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.S.; Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Stedman, R.C.; Luloff, A.E. Wildfire perception and community change. Rural. Sociol. 2010, 75, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.S.; Willcox, A.; Luloff, A.E.C.; Finley, J.G.; Hodges, D. Public Perceptions of Values Associated with Wildfire Protection at the Wildland-Urban Interface: A Synthesis of National Findings. In Landscape Reclamation—Rising from What’s Left; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaiologou, P.; Kalabokidis, K.; Troumbis, A.; Day, M.A.; Nielsen-Pincus, M.; Ager, A.A. Socio-Ecological Perceptions of Wildfire Management and Effects in Greece. Fire 2021, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmenta, R.; Zabala, A.; Daeli, W.; Phelps, J. Perceptions across scales of governance and the Indonesian peatland fires. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 46, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, S. Understanding public perspectives of wildfire risk. In Wildfire Risk, Human Perceptions and Management Implications; Martin, W.E., Raish, C., Kent, B., Eds.; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Terrén, D.M.; Cardil, A.; Kobziar, L.N. Practitioner Perceptions of Wildland Fire Management across South Europe and Latin America. Forests 2016, 7, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.; Oliveira, S.; Zêzere, J.L.; Viegas, D.X. Uncovering the perception regarding wildfires of residents with different characteristics. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 43, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, V.; Elia, M.; Lovreglio, R.; Correia, F.; Tedim, F. The 2017 Extreme Wildfires Events in Portugal through the Perceptions of Volunteer and Professional Firefighters. Fire 2023, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safak, I.; Okan, T.; Karademir, D. Perceptions of Turkish Forest Firefighters on In-Service Trainings. Fire 2023, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo-Leyenda, B.; Villa-Vicente, J.G.; Delogu, G.M.; Rodríguez-Marroyo, J.A.; Molina-Terrén, D.M. Perceptions of Heat Stress, Heat Strain and Mitigation Practices in Wildfire Suppression across Southern Europe and Latin America. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, S.; Shenoi, E.A.; Garfin, D.R.; Wu, J. Assessing Perception of Wildfires and Related Impacts among Adult Residents of Southern California. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuss-Girona, S.; Soy, E.; Canaleta, G.; Alay, O.; Domènech, R.; Prat-Guitart, N. Fire Flocks: Participating Farmers’ Perceptions after Five Years of Development. Land 2022, 11, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapiains, R.; Ugarte, A.M.; Aldunce, P.; Marchant, G.; Romero, J.A.; González, M.E.; Inostroza-Lazo, V. Local Perceptions of Fires Risk and Policy Implications in the Hills of Valparaíso, Chile. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vides-Almonacid, R.; Reichle, S.; Padilla, F. Planificación Ecorregional del Bosque Seco Chiquitano; Editorial Fundación para la Conservación del Bosque Chiquitano: Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, 2007; p. 245. [Google Scholar]

- Portillo-Quintero, C.A.; Sánchez-Azofeifa, G.A. Extent and conservation of tropical dry forests in the Americas. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killeen, T.J.; Chavez, E.; Peña-Claros, M.; Toledo, M.; Arroyo, L.; Caballero, J.; Guillén, R.; Quevedo, R.; Saldias, M.; Soria, L. The Chiquitano dry forest, the transition between humid and dry forest in eastern lowland Bolivia. Syst. Assoc. Spec. 2006, 69, 213. [Google Scholar]

- Maillard, O.; Pinto-Herrera, C.; Vides-Almonacid, R.; Pozo, P.; Belaunde, C.; Mielich, N.; Azurduy, H.; Cuellar, R.L. Public Policies and Social Actions to Prevent the Loss of the Chiquitano Dry Forest. Sustainability 2024, 16, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 2025. Available online: https://www.ine.gob.bo (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Champ, P.; Brenkert-Smith, H. Is seeing believing? Perceptions of wildfire risk over time. Risk Anal. 2016, 36, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devisscher, T.; Malhi, Y.; Boyd, E. Deliberation for wildfire risk management: Addressing conflicting views in the Chiquitania, Bolivia. Geogr. J. 2019, 185, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killeen, T.J.; Siles, T.M.; Grimwood, T.; Tieszen, L.L.; Steininger, M.K.; Tucker, C.J.; Panfil, S.N. Habitat heterogeneity on a forest-savanna ecotone in Noel Kempff Mercado National Park (Santa Cruz, Bolivia); Implications for the long-term conservation of biodiversity in a changing climate. In How Landscapes Change: Human Disturbance and Ecosystem Disruptions in the Americas; Bradshaw, G.A., Marquet, P., Eds.; Ecological, Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 162, p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Maillard, O.; Vides-Almonacid, R.; Flores-Valencia, M.; Coronado, R.; Vogt, P.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Azurduy, H.; Anívarro, R.; Cuellar, R.L. Relationship of Forest Cover Fragmentation and Drought with the Occurrence of Forest Fires in the Department of Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Forests 2020, 11, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, S.H.; Santín, C. Global trends in wildfire and its impacts: Perceptions versus realities in a changing world. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, P.M. Estimación del Efecto Económico Sobre los Medios de Vida en las Áreas Afectadas del Departamento de Santa Cruz por los Incendios Forestales y la Sequía; Fundación para la Conservación del Bosque Chiquitano (FCBC): Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, 2020; 47p. [Google Scholar]

- Apaza, L. Evaluación de los Medios de Vida de Comunidades Chiquitanas Postincendio; WWF-Bolivia, Fundación Amigos de la Naturaleza y Gobierno Autónomo Departamental de Santa Cruz: Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maillard, O.S.; Angulo, R.; Vides-Almonacid, D.; Rumiz, P.; Vogt, O.; Monroy-Vilchis, H.; Justiniano, H.; Azurduy, R.; Coronado, C.; Venegas, R.L.; et al. Integridad del paisaje y riesgos de degradación del hábitat del jaguar (Panthera onca) en áreas ganaderas de las tierras bajas de Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Ecol. Boliv. 2020, 55, 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, L.; Pinto, M.A.; Aponte, M.A.; Ledezma, R.; Soto, D.; Peñaranda, M.; Nina, R.; Gutiérrez, S.; Rivero, K.; Toledo, M. Impacto de incendios forestales en la biodiversidad del Bosque Seco Chiquitano. Informe Técnico. In Proyecto Bases del Conocimiento Para la Restauración; Fundación para la Conservación del Bosque Chiquitano: Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia; Museo de Historia Natural Noel Kempff Mercado: Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, L.F.; Quispe, L.C.; Suárez, F.A. Muerte de mamíferos por incendios de 2019 en la Chiquitanía. Ecol. Boliv. 2021, 56, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, L.; Giménez, M.; Villalba, R. La dendrocronología como herramienta útil para evaluar la variabilidad del crecimiento radial en 11 especies tropicales de Bolivia. Ecol. Boliv. 2023, 58, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Maillard, O. Post-Fire Natural Regeneration Trends in Bolivia: 2001–2021. Fire 2023, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, K.A.; Fredericksen, T.S.; Morales, F.; Kennard, D.; Putz, F.E.; Mostacedo, B.; Toledo, M. Post-fire tree re-generation in lowland Bolivia: Implications for fire management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 185, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostacedo, B.; Viruez, A.; Varon, Y.; Paz-Roca, A.; Parada, V.; Veliz, V. Tree survival and resprouting after wildfire in tropical dry and subhumid ecosystems of Chiquitania, Bolivia. Trees For. People 2022, 10, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO Strategy on Forest Fire Management. 2019. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/db2fcab3-7369-4e4a-9f10-d81530fe32c6/content (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- DavalosYoshida, A.; Gil-Herrera, R.J. The landlocked condition as determinant for development of internet: The Bolivian case. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2020, 13, 3521–3537. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).