Harmful Algal Blooms as Emerging Marine Pollutants: A Review of Monitoring, Risk Assessment, and Management with a Mexican Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Year | Contribution/Advancement | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | Early conceptual framework for HAB prediction; foundational ecological indicators. | [18] |

| 1996 | Dynamic HAB soft sensor using hyperspectral image data mining for accessory pigment analysis. | [19] |

| 2009 | Integration of morphological and molecular data (rbcL, ITS) to enhance taxonomic detection of HAB species. | [20] |

| 2011 | Machine learning-based spatio-temporal data mining for HAB detection in the Gulf of Mexico; introduction of cubical neighborhood spectral retrieval. | [21] |

| 2017a | Neural-network processors for detecting HABs in optically complex waters using MERIS 10-year archive. | [22] |

| 2017b | Forty-three algorithmic combinations for HAB prediction using multispectral and hyperspectral bands. | [23] |

| 2017c | Semi-analytical spectral matching and novel algorithms for chlorophyll-a retrieval supporting eutrophication control. | [24] |

| 2018 | Time-series LSTM model for HAB prediction in four major South Korean rivers. | [25] |

| 2020 | Evaluation of band-ratio vs. machine learning models for Chl-a prediction as a proxy for cyanobacterial blooms. | [26] |

| 2020 | Real-time blue tide prediction model using sulfur concentration derived from GOCI observations. | [27] |

| 2021 | Synoptic review of ML approaches for HAB and biotoxin prediction (ANN, RF, SVM, and PGMs). | [28] |

| 2021 | ML-based short-term HAB prediction using optimized environmental feature selection. | [29] |

| 2022 | CNN-LSTM model combining spatio-temporal features for Chl-a prediction; improved accuracy and training speed. | [30] |

| 2022 | Integrated CNN-LSTM model for predicting CyanoHAB spatial extent. | [11] |

| 2022 | Hybrid XG-LSTM (XGBoost-Long Short-Term Memory) architecture predicting algal cell density and microcystins in Three Gorges Reservoir. | [31] |

| 2022 | Spatial prediction of Cochlodinium polykrikoides blooms using CNN-based domain-specific configurations. | [32] |

| 2022 | Review of monitoring, modeling, and long-term projection of HABs in China, including early-warning remote sensing. | [33] |

| 2023 | Review of freshwater HAB increases; assessment of hydrodynamic reservoir management strategies affecting bloom occurrence. | [34] |

| 2024 | Global HAB trend review showing 44% increase from 2000s to 2010s; emphasizes integrated monitoring networks and data fusion for improved forecasts. | [3] |

| 2024 | One-Health review on HAB toxins in marine and freshwater systems; integration of human, animal, and environmental surveillance. | [4] |

| 2025 | Review of eutrophication-driven coastal HAB expansion; assessment of physical, chemical, and biological treatment strategies. | [9] |

| 2025 | Review of links between climate change-driven CyanoHAB proliferation and dermatologic impacts; calls for improved exposure monitoring. | [10] |

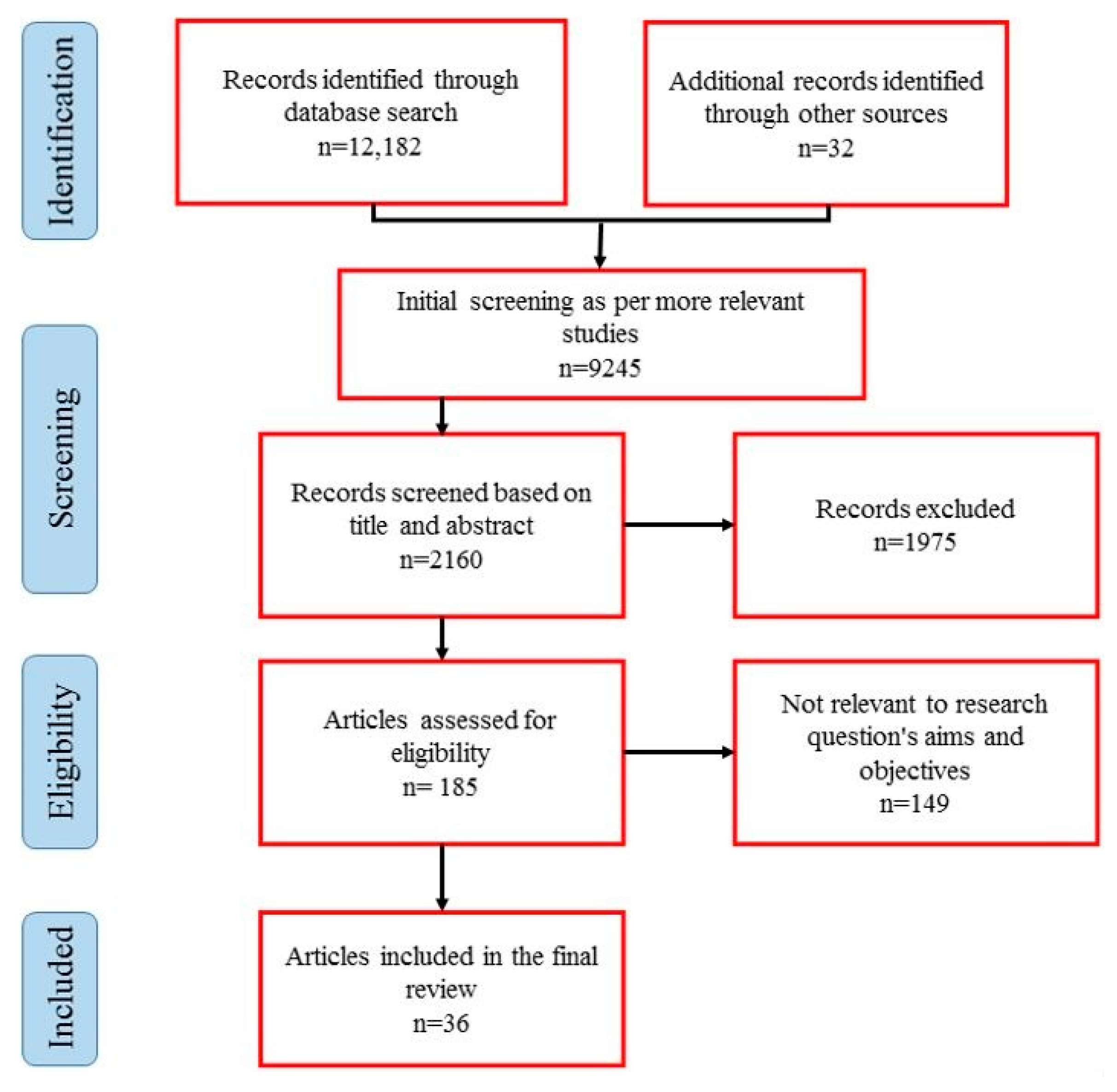

2. Methodology

2.1. Scope and Focus

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

2.3. Screening and Eligibility Criteria

- o

- Direct relevance to HAB monitoring, prediction, risk analysis, or management;

- o

- Publication in peer-reviewed journals;

- o

- Availability of full text;

- o

- Studies providing conceptual, methodological, or applied insights.

2.4. Data Extraction and Categorization

- o

- Monitoring and detection techniques (remote sensing, in situ sensors, machine learning, and molecular tools);

- o

- Risk assessment approaches, including anthropogenic, esthetic, and environmental dimensions;

- o

- Modeling frameworks for HAB prediction;

- o

- Governance, policy responses, and mitigation strategies;

- o

- Documented case studies, with emphasis on Mexican coastal systems.

3. Risk Assessment Methods in HABs

3.1. Overview of HAB Risk Assessment Approaches

- (1)

- Human health and anthropogenic risk assessment;

- (2)

- Socio-esthetic and cultural ecosystem impacts;

- (3)

- Environmental and ecological risk assessment.

3.2. Anthropogenic and Human Health Risk Assessment

| Authors | Pollution | Method | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| [43] | Karenia brevis | Provide a risk assessment framework for the recognition and prioritization of the required information to determine human health risks | Use of obtained framework to focus and solve the data gaps |

| [44] | Pseudo-nitzschia and domoic acid (DA) | Implementation of California HAB risk mapping (C-HARM) by using a blend of numerical models, ecological forecast models, and satellite ocean color imagery | Best correlation between DA measured with solid phase adsorption toxin tracking (SPATT) and marine mammal strandings from DA toxicosis |

| [47] | HABs | Performing laboratory simulation experiments to investigate the effect of algal blooms on the cycling of arsenic by conceptual modeling | Direct connection between release of acute arsenic in water and the atmosphere and dosage of harmful algal bloom |

| [42] | Escherichia coli, cyanobacterial harmful algae bloom (cHAB), and V. cholerae | Microbial risk analysis based on measuring the concentration of pollution in different sites of bathing water | Observing exceedances of moderate- and high-risk thresholds for cHAB |

| [45] | Domoic acid | Risk assessment by policymaking and checking with federal laws | Fundamental reasons for HAB controlling with increasing trust-building in society |

| [46] | Domoic acid (DA) and saxitoxin (PST) | Detection of toxic concentration by experimental methods such as ELISA analyses and LC-FLD confirmation analyses | DA and PST have a high potential for storage in body of fish that are eaten by larger predators and finally enter the human chain food |

3.3. Socio-Esthetic and Cultural Risk Dimensions

| Authors | Pollution | Method | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| [48] | Cyanobacteria | Risk assessment by chlorophyll-a threshold assignment for eutrophication control | Implementation of alert management system in eutrophication event |

| [49] | Microcystin | Creating a framework using a statistical model (Bernoulli model) for evaluation of water quality specification | Nutrient management is the best option to reduce the frequency of high-microcystin events |

| [45] | Domoic acid | Risk assessment by policymaking and checking with federal laws | Fundamental reasons for HAB controlling with increasing trust-building in society |

3.4. Environmental and Ecological Risk Assessment

| Study | Pollution | Method | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| [44] | Pseudo-nitzschia and domoic acid (DA) | Implementation of California HAB risk mapping (C-HARM) by using a blend of numerical models, ecological forecast models, and satellite ocean color imagery | Best correlation between DA measured with solid phase adsorption toxin tracking (SPATT) and marine mammal strandings from DA toxicosis |

| [49] | Microcystin | Creating a framework using a statistical model (Bernoulli model) for evaluation of water quality specification | Nutrient management is the best option to reduce the frequency of high-microcystin events |

| [47] | HABs | Performing laboratory simulation experiments to investigate the effect of algal blooms on the cycling of arsenic by conceptual modeling | Direct connection between release of acute arsenic in water and the atmosphere and dosage of harmful algal bloom |

| [56] | HABs | Risk assessment by mathematical methods | Eutrophication indexes are valid tools due to HAB detection and controlling |

| [57] | Filamentous Cyanobacteria, Planktothrix sp., Limnothrix sp., and Cylindrospermopsis Raciborskii | Experimental measurement of water quality indicators | High relevance between filamentous cyanobacteria abundance and increasing water temperature |

| [55] | Ciguatoxins (CTXs) | Using the solid phase adsorption toxin tracking (SPATT) method | In areas where the ciguatera risk is unknown or considered low-to-moderate, increasing the amount of resin and time of deployment could help improve toxin detection. |

| [45] | Domoic acid | Risk assessment by policymaking and checking with federal laws | Fundamental reasons for HAB controlling with increasing trust-building in society |

| [58] | HABs | Risk assessment by methodological approaches based on expert view information elicitation using questionnaire and data analyses by two-way analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) | Intensity of HABs is increased in May-June |

| [54] | Prymnesium parvum harmful algae bloom | Survey on river and mapping risk assessment based on Prymnesium parvum emission | Prymnesium parvum can cause repetition of HABs in rivers and increasing ecological risks |

3.5. Synthesis of Integrated RA Needs

- Improved coupling of ecological and socio-economic indicators;

- Quantitative tools for BHAB and AHAB phases;

- Incorporation of climate-projection scenarios;

- Enhanced public-communication and risk-perception frameworks;

- Harmonization of remote sensing, machine learning, and policy-based RA approaches.

4. HAB Risk Analysis in Mexican Cases

5. HABs and Policymaking

6. Online Monitoring and Assessment Systems

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olson, N.E.; Cooke, M.E.; Shi, J.H.; Birbeck, J.A.; Westrick, J.A.; Ault, A.P. Harmful Algal Bloom Toxins in Aerosol Generated from Inland Lake Water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 4769–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, K. A Review of Climate Change Impact Studies on Harmful Algal Blooms. Phycology 2022, 2, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Hou, X.; Qin, B.; Kutser, T.; Qu, F.; Chen, N.; Paerl, H.W.; Zheng, C. Harmful Algal Blooms in Inland Waters. Nat. Rev. Earth Env. 2024, 5, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messineo, V.; Bruno, M.; De Pace, R. The Role of Cyano-HAB (Cyanobacteria Harmful Algal Blooms) in the One Health Approach to Global Health. Hydrobiology 2024, 3, 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, L.E.; Jerez, E.; Stephan, W.B.B.; Cassedy, A.; Bean, J.A.; Reich, A.; Kirkpatrick, B.; Backer, L.; Nierenberg, K.; Watkins, S.; et al. Evaluation of Harmful Algal Bloom Outreach Activities. Mar. Drugs 2007, 5, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Chun, S.-J.; Baek, S.-S.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, P.-J.; Son, M.; Cho, K.H.; Ahn, C.-Y.; Oh, H.-M. Unique Microbial Module Regulates the Harmful Algal Bloom (Cochlodinium Polykrikoides) and Shifts the Microbial Community along the Southern Coast of Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Lin, Q.; Li, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, X. Atmospheric Transport of Nutrients during a Harmful Algal Bloom Event. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 34, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ni, W.; Zhang, F.; Glibert, P.M.; Lin, C.-H. (Michelle) Climate-Induced Interannual Variability and Projected Change of Two Harmful Algal Bloom Taxa in Chesapeake Bay, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744, 140947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-M.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Emmanuel, C.; Fan, T.-H.; Deng, W.; Zhang, Y.-F. Interdisciplinary Strategies for the Management of Harmful Algal Blooms: Prospects & Comprehensive Review. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, J.; Parker, E.R. Climate Change, Harmful Algal Blooms, and Cutaneous Disease. JAAD Rev. 2025, 4, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Han, L.; Li, L. A Deep Learning Method for Cyanobacterial Harmful Algae Blooms Prediction in Taihu Lake, China. Harmful Algae 2022, 113, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniyar, C.B.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, D.R. Continuous and Synoptic Assessment of Indian Inland Waters for Harmful Algae Blooms. Harmful Algae 2022, 111, 102160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolny, J.L.; McCollough, C.B.; Rosales, D.S.; Pitula, J.S. Harmful Algal Bloom Species in the St. Martin River: Surveying the Headwaters of Northern Maryland’s Coastal Bays. J. Coast. Res. 2022, 38, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapucci, C.; Maselli, F.; Chini Zittelli, G.; Betti, G.; Vannucchi, V.; Perna, M.; Taddei, S.; Gozzini, B.; Ortolani, A.; Brandini, C. Towards the Prediction of Favourable Conditions for the Harmful Algal Bloom Onset of Ostreopsis Ovata in the Ligurian Sea Based on Satellite and Model Data. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, S.; Luo, G.; Zheng, W.; Tian, Y.; Lei, X.; Yao, L.; Wu, C.; Xu, H. A Novel Algicidal Bacterium, Microbulbifer Sp. YX04, Triggered Oxidative Damage and Autophagic Cell Death in Phaeocystis Globosa, Which Causes Harmful Algal Blooms. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00934-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElFar, O.A.; Aron, N.S.M.; Chew, K.W.; Show, P.L. Sustainable Management of Algal Blooms in Ponds and Rivers. In Biomass, Biofuels, Biochemicals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 431–444. ISBN 9780323885119. [Google Scholar]

- Samarkhanov, K.; Mirasbekov, Y.; Meirkhanova, A.; Zhumakhanova, A.; Malashenkov, D.; Kovaldji, A.; Barteneva, N.S. Long-Term Temperature Trend in Kamchatka Supports Expansion of Harmful Algae 2022. bioRxiv 2022, 485652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidinger, K.A.; Haddad, K. Biologic and Hydrographic Aspects of Red Tides. Bioscience 1981, 31, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L.L. Remote Sensing of Algal Bloom Dynamics. Bioscience 1996, 46, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leliaert, F.; Zhang, X.; Ye, N.; Malta, E.; Engelen, A.H.; Mineur, F.; Verbruggen, H.; De Clerck, O. Research Note: Identity of the Qingdao Algal Bloom. Phycol. Res. 2009, 57, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokaraju, B.; Durbha, S.S.; King, R.L.; Younan, N.H. A Machine Learning Based Spatio-Temporal Data Mining Approach for Detection of Harmful Algal Blooms in the Gulf of Mexico. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2011, 4, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.; Strand, M.; Higa, H.; Kim, H.; Kazuhiro, K.; Oki, K.; Oki, T. Evaluation of MERIS Chlorophyll-a Retrieval Processors in a Complex Turbid Lake Kasumigaura over a 10-Year Mission. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.; Higa, H.; Kim, H.; Kazuhiro, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Oki, K.; Oki, T. Multi-Algorithm Indices and Look-Up Table for Chlorophyll-a Retrieval in Highly Turbid Water Bodies Using Multispectral Data. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.; Higa, H.; Kim, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Oki, K.; Oki, T. Assessment of Chlorophyll-a Algorithms Considering Different Trophic Statuses and Optimal Bands. Sensors 2017, 17, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, D. Improved Prediction of Harmful Algal Blooms in Four Major South Korea’s Rivers Using Deep Learning Models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-Q.; Ha, N.-T.; Pham, T.-L. Inland Harmful Cyanobacterial Bloom Prediction in the Eutrophic Tri An Reservoir Using Satellite Band Ratio and Machine Learning Approaches. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 9135–9151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higa, H.; Sugahara, S.; Salem, S.I.; Nakamura, Y.; Suzuki, T. An Estimation Method for Blue Tide Distribution in Tokyo Bay Based on Sulfur Concentrations Using Geostationary Ocean Color Imager (GOCI). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2020, 235, 106615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.C.; Reis Costa, P.; Vinga, S.; Krippahl, L.; Lopes, M.B. A Review of Recent Machine Learning Advances for Forecasting Harmful Algal Blooms and Shellfish Contamination. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Gao, R.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Z.-P. Predicting Coastal Algal Blooms with Environmental Factors by Machine Learning Methods. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 123, 107334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, L.; Shaoyang, C.; Zhenyan, C.; Xing, W.; Yun, X.; Li, X.; Yanwei, G.; Tingting, W.; Xuefeng, Z.; Siqi, L. Long-Term Prediction of Sea Surface Chlorophyll-a Concentration Based on the Combination of Spatio-Temporal Features. Water Res. 2022, 211, 118040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, K.; Ouyang, T.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Zhou, B.; Wu, Z.; Shang, M. Temporal Prediction of Algal Parameters in Three Gorges Reservoir Based on Highly Time-Resolved Monitoring and Long Short-Term Memory Network. J. Hydrol. 2022, 605, 127304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Park, Y.; Lim, W.-A.; Min, S.-H.; Lee, J.-S. Convolution Neural Network for the Prediction of Cochlodinium Polykrikoides Bloom in the South Sea of Korea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Bao, M.; Lou, X.; Zhou, Z.; Yin, K. Monitoring, Modeling and Projection of Harmful Algal Blooms in China. Harmful Algae 2022, 111, 102164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, E.J.; Ryder, J.L. A Critical Review of Operational Strategies for the Management of Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) in Inland Reservoirs. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 330, 117141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondeau-Patissier, D.; Gower, J.F.R.; Dekker, A.G.; Phinn, S.R.; Brando, V.E. A Review of Ocean Color Remote Sensing Methods and Statistical Techniques for the Detection, Mapping and Analysis of Phytoplankton Blooms in Coastal and Open Oceans. Prog. Ocean. 2014, 123, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, H.A.; Tarnecki, J.H.; Grüss, A.; Babcock, E.A.; Sagarese, S.R.; Ainsworth, C.H.; Gray DiLeone, A.M. A Revised Diet Matrix to Improve the Parameterization of a West Florida Shelf Ecopath Model for Understanding Harmful Algal Bloom Impacts. Ecol. Model. 2020, 416, 108890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhura, S.; Dedeepya, P. A Comparative Analysis of Rainfall-Prediction Using Optimized Machine Learning Algorithms. Environ. Ind. Lett. (EIL) 2024, 2, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylfiu, B.; Marinova, G.; Hajrizi, E.; Qehaja, B. Cluster Analysis of Merger and Acquisition Patterns in the Electronic Design Automation Industry Using Machine Learning Techniques. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Interdiscip. Sci. (IJITIS) 2025, 8, 784–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tao, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Q.; Jiang, Z.; He, S.; Huang, H.; Mao, Z. Assessment of VIIRS on the Identification of Harmful Algal Bloom Types in the Coasts of the East China Sea. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Park, J.; Zhao, K.; Londo, A.; Khanal, S. Monitoring Harmful Algal Blooms and Water Quality Using Sentinel-3 OLCI Satellite Imagery with Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E.; Bernard, S. Satellite Ocean Color Based Harmful Algal Bloom Indicators for Aquaculture Decision Support in the Southern Benguela. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyraite, G.; Kataržytė, M.; Overlingė, D.; Vaičiūtė, D.; Jonikaitė, E.; Schernewski, G. Skip the Dip—Avoid the Risk? Integrated Microbiological Water Quality Assessment in the South-Eastern Baltic Sea Coastal Waters. Water 2020, 12, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahl, P.L. Harmful Algal Bloom-Associated Marine Toxins: A Risk Assessment Framework. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2009, 64, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.R.; Kudela, R.M.; Kahru, M.; Chao, Y.; Rosenfeld, L.K.; Bahr, F.L.; Anderson, D.M.; Norris, T.A. Initial Skill Assessment of the California Harmful Algae Risk Mapping (C-HARM) System. Harmful Algae 2016, 59, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrom, J.A.; Moore, S.K.; Klinger, T. Examining Harmful Algal Blooms through a Disaster Risk Management Lens: A Case Study of the 2015 U.S. West Coast Domoic Acid Event. Harmful Algae 2020, 94, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, J.L.; Jensen, S.-K.; McConnell, B.; Fraser, S.; Cummings, C.; Lacaze, J.-P.; Hermann, G.; Bresnan, E.; Dean, K.J.; Turner, A.D.; et al. Toxins from Harmful Algae in Fish from Scottish Coastal Waters. Harmful Algae 2021, 105, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Sun, G.; Pan, G. Impact of Eutrophication on Arsenic Cycling in Freshwaters. Water Res. 2019, 150, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaji, H.; Sytar, O.; Brestic, M.; Samborska, I.; Cetner, M.; Carpentier, C. Risk Assessment of Urban Lake Water Quality Based on In-Situ Cyanobacterial and Total Chlorophyll-a Monitoring. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2016, 25, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, N.E.; Javed, A.; Shimoda, Y.; Zastepa, A.; Watson, S.; Mugalingam, S.; Arhonditsis, G.B. A Bayesian Risk Assessment Framework for Microcystin Violations of Drinking Water and Recreational Standards in the Bay of Quinte, Lake Ontario, Canada. Water Res. 2019, 162, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Pourjafar, M.; Taghvaee, A.; Azadfallah, P. Quality Enhancement of Environmental Aesthetics Experience Through Ecological Assessment Case Study: River of Darabad Valley, Tehran, Iran. Curr. World Environ. 2014, 9, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribot, A.-S.; Deter, J.; Mouquet, N. Integrating the Aesthetic Value of Landscapes and Biological Diversity. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20180971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rossi, G. To What Extent Do Psychological Distance and Knowledge Mediate the Impact of Algae Blooms on Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Lake Champlain Basin? Master’s Thesis, UVM Patrick Leahy Honors College, Burlington, VT, USA, 2018. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14849/5190 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Goodrich, S.; Tong, S.T.Y. Recreator Perspectives on Harmful Algal Blooms in Ohio. Environ. Sociol. 2025, 11, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, K.J.; Wellman, D.I.; Kingsbury, J.W.; Cincotta, D.A.; Clayton, J.L.; Eliason, K.M.; Jernejcic, F.A.; Owens, N.V.; Smith, D.M. A Case Study of a Prymnesium Parvum Harmful Algae Bloom in the Ohio River Drainage: Impact, Recovery and Potential for Future Invasions/Range Expansion. Water 2021, 13, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roué, M.; Smith, K.F.; Sibat, M.; Viallon, J.; Henry, K.; Ung, A.; Biessy, L.; Hess, P.; Darius, H.T.; Chinain, M. Assessment of Ciguatera and Other Phycotoxin-Related Risks in Anaho Bay (Nuku Hiva Island, French Polynesia): Molecular, Toxicological, and Chemical Analyses of Passive Samplers. Toxins 2020, 12, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Xu, X.; Wang, P.; Liang, S.; Li, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, X. Methodology for Forecast and Control of Coastal Harmful Algal Blooms by Embedding a Compound Eutrophication Index into the Ecological Risk Index. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 139404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Tang, Q.; Gu, J.; Lei, L.; Han, B.-P. Species Diversity and Seasonal Dynamics of Filamentous Cyanobacteria in Urban Reservoirs for Drinking Water Supply in Tropical China. Ecotoxicology 2020, 29, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, J.A.; Moutopoulos, D.K.; Tzovenis, I. Semi-Quantitative Risk Assessment of Mediterranean Mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis L.) Harvesting Bans Due to Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB) Incidents in Greece. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2020, 24, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, H.; Ralph, G.M.; Rogers-Bennett, L. Abalones at Risk: A Global Red List Assessment of Haliotis in a Changing Climate. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, S.R.; Tester, P.A.; Kunkel, K.E.; Moore, S.K.; Litaker, R.W. Effects of Ocean Warming on Growth and Distribution of Dinoflagellates Associated with Ciguatera Fish Poisoning in the Caribbean. Ecol. Model. 2015, 316, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajardo, G.; Morón-López, J.; Vergara, K.; Ueki, S.; Guzmán, L.; Espinoza-González, O.; Sandoval, A.; Fuenzalida, G.; Murillo, A.A.; Riquelme, C.; et al. The Holobiome of Marine Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs): A Novel Ecosystem-Based Approach for Implementing Predictive Capabilities and Managing Decisions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 143, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, H.; Alvarez, S.; Bahja, F. What’s in a Name? Political and Economic Concepts Differ in Social Media References to Harmful Algae Blooms. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 357, 120799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ArcGIS Dashboards. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Harmful Algal Blooms Observing System. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- HABs Dashboard. Available online: https://www.pa.gov/agencies/health/programs/environmental-health/habs-dashboard (accessed on 1 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Masoomi, S.R.; Ganji, M.; Annuk, A.; Eftekhari, M.; Mahmood, A.; Gheibi, M.; Moezzi, R. Harmful Algal Blooms as Emerging Marine Pollutants: A Review of Monitoring, Risk Assessment, and Management with a Mexican Case Study. Pollutants 2026, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants6010004

Masoomi SR, Ganji M, Annuk A, Eftekhari M, Mahmood A, Gheibi M, Moezzi R. Harmful Algal Blooms as Emerging Marine Pollutants: A Review of Monitoring, Risk Assessment, and Management with a Mexican Case Study. Pollutants. 2026; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants6010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleMasoomi, Seyyed Roohollah, Mohammadamin Ganji, Andres Annuk, Mohammad Eftekhari, Aamir Mahmood, Mohammad Gheibi, and Reza Moezzi. 2026. "Harmful Algal Blooms as Emerging Marine Pollutants: A Review of Monitoring, Risk Assessment, and Management with a Mexican Case Study" Pollutants 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants6010004

APA StyleMasoomi, S. R., Ganji, M., Annuk, A., Eftekhari, M., Mahmood, A., Gheibi, M., & Moezzi, R. (2026). Harmful Algal Blooms as Emerging Marine Pollutants: A Review of Monitoring, Risk Assessment, and Management with a Mexican Case Study. Pollutants, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants6010004