Microplastics in the Rural Environment: Sources, Transport, and Impacts

Abstract

1. Introduction

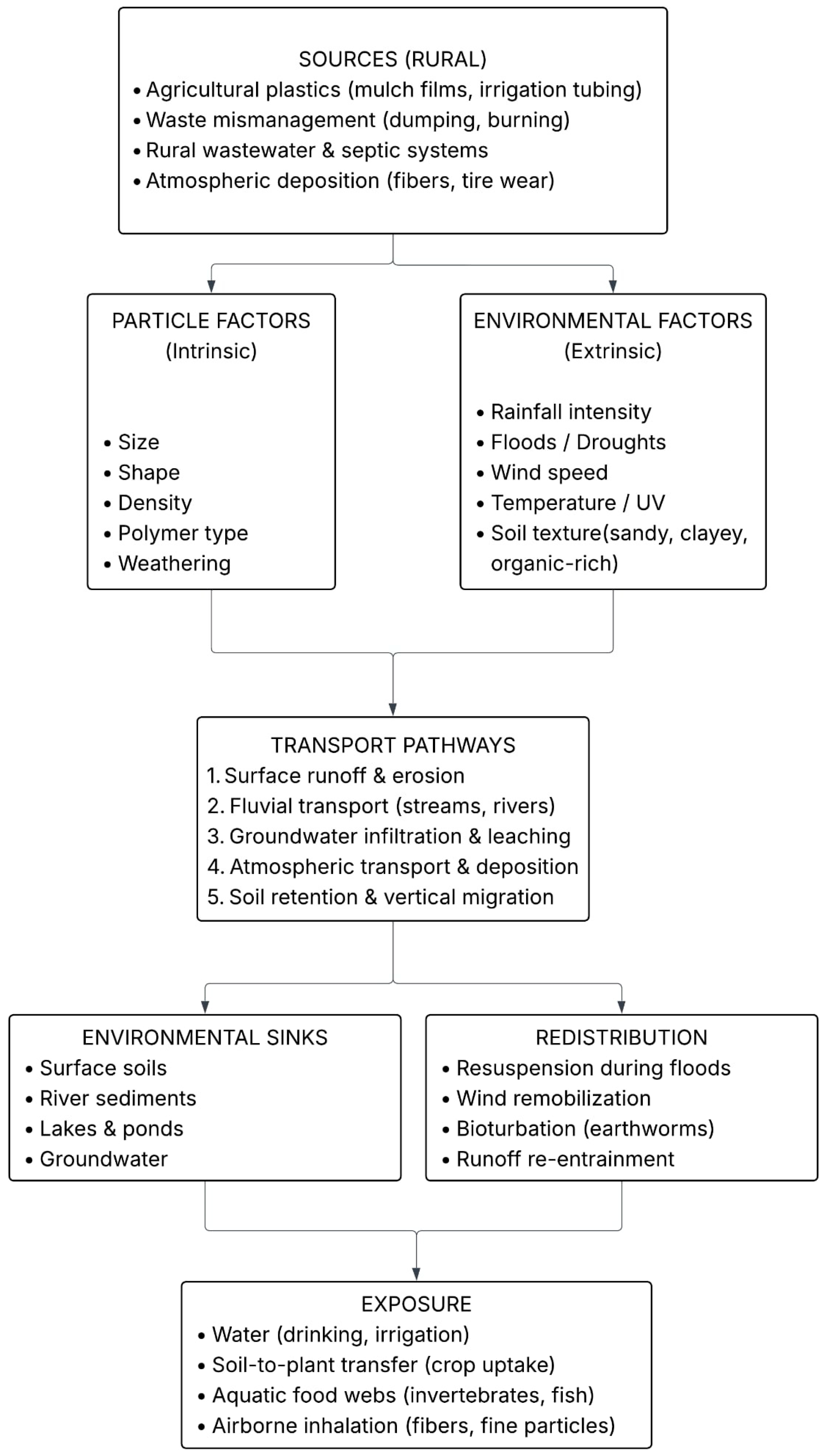

2. Sources of Microplastics in Rural Environments

2.1. Rural-Specific Sources

2.1.1. Anthropogenic Sources of Microplastics in Rural Areas

2.1.2. Agricultural Activities and Plastic Mulching

2.1.3. Domestic Waste and Improper Disposal

2.1.4. Rural Wastewater and Septic Systems

2.1.5. Microplastics in Rural Lakes and Ponds

2.1.6. Microplastics in Soils and Agricultural Fields

2.1.7. Microplastics in Rural Groundwater

2.1.8. Microplastics in Rural Sediments

2.2. Indirect Sources

2.2.1. Road Runoff and Tire Wear

2.2.2. Industrial and Small-Scale Manufacturing Sources

2.2.3. Recreational Activities and Tourism

2.2.4. Hydrological and Atmospheric Transport Mechanisms in Rural Systems

2.2.5. Surface Runoff and Soil Erosion

2.2.6. Stream and River Transport

2.2.7. Groundwater Infiltration and Leaching

2.2.8. Wind and Airborne Microplastics

2.2.9. Microplastics in Rivers and Streams

2.3. General/Non-Specific Sources

2.3.1. Environmental Distribution of Microplastics

2.3.2. Characteristics and Types of Microplastics Found

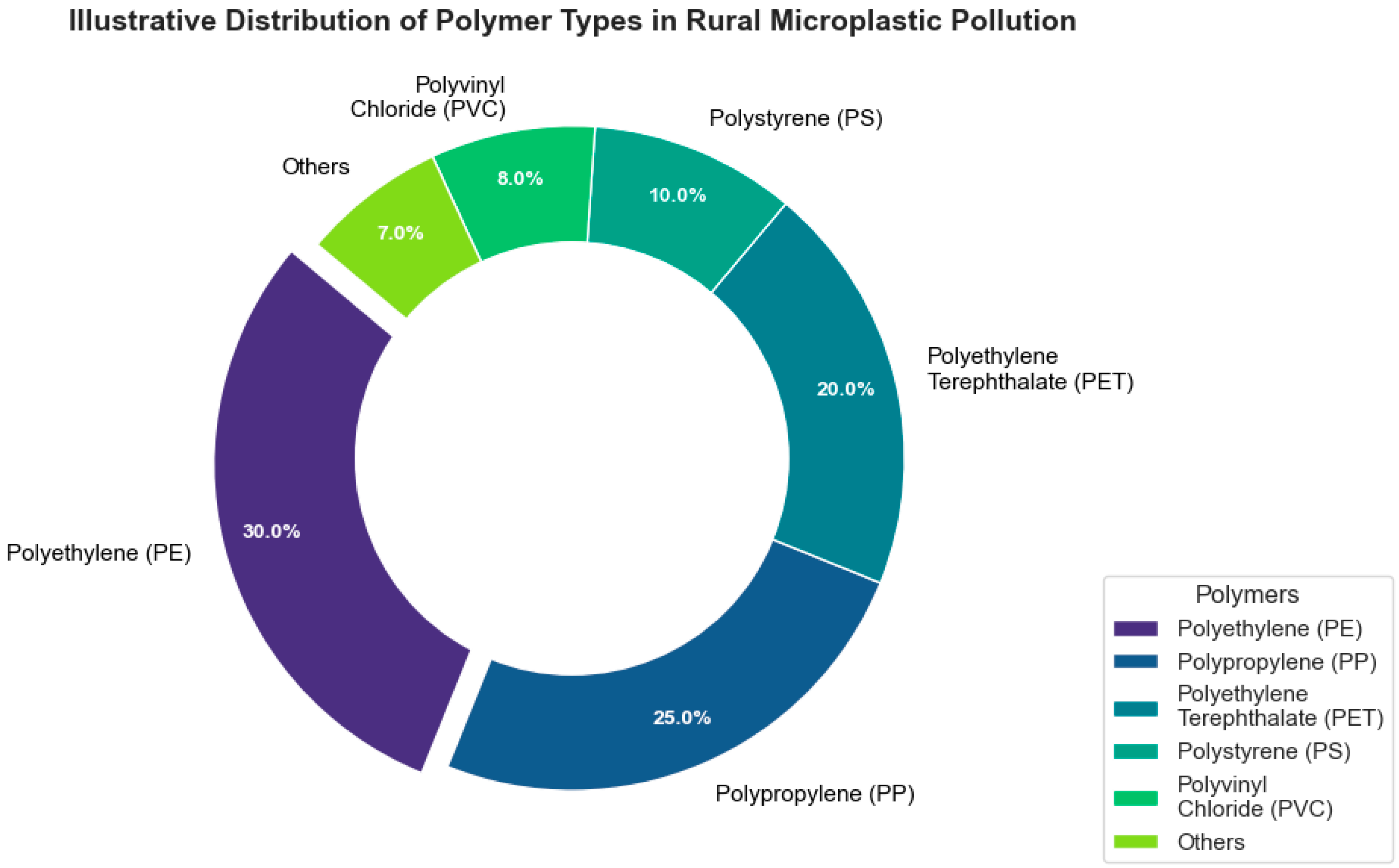

2.3.3. Polymer Composition

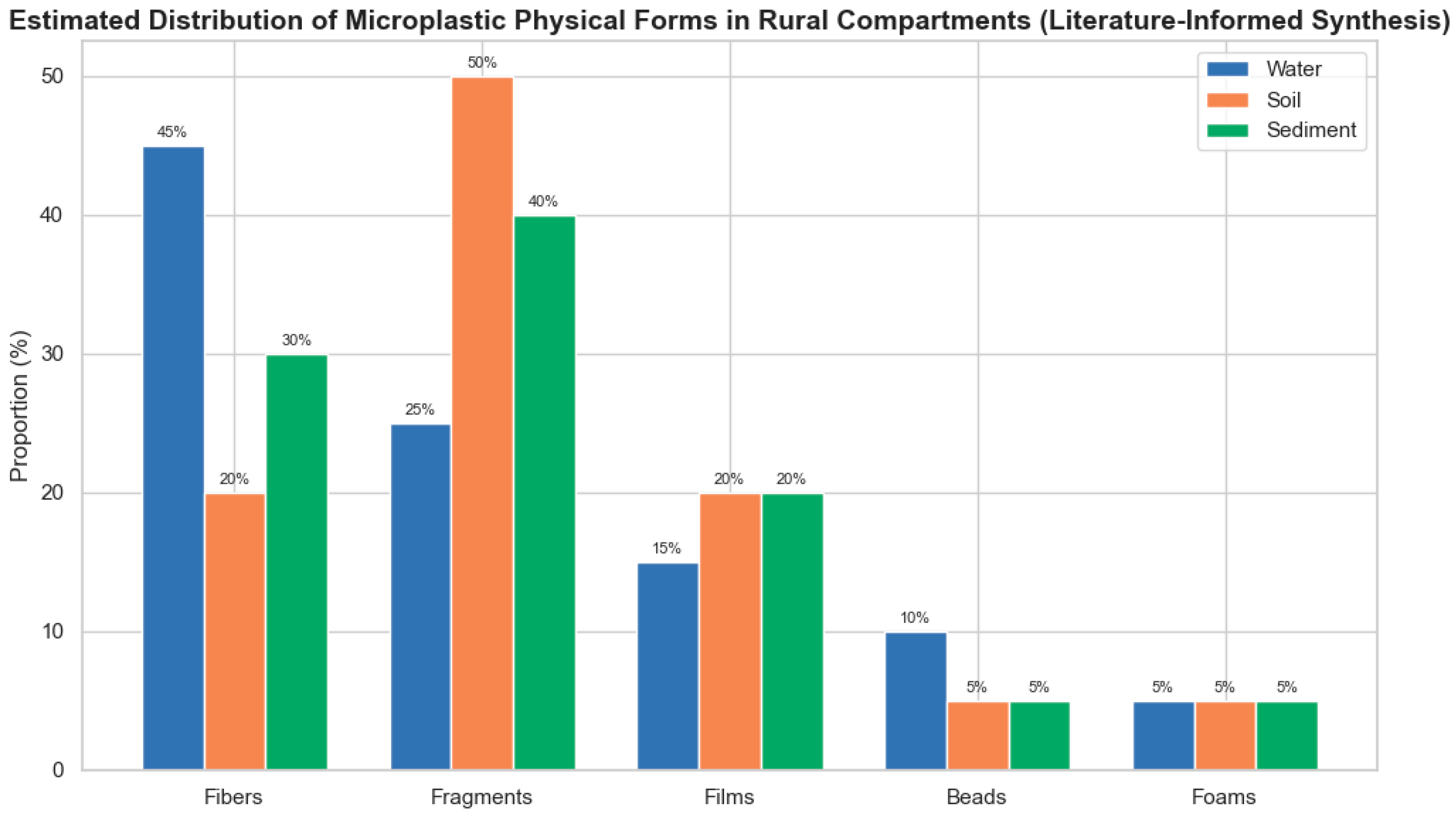

2.3.4. Physical Forms: Fibers, Fragments, Films, and Beads

- Fibers: Elongated, thread-like particles primarily derived from synthetic textiles and fishing gear. These are particularly dominant in samples from atmospheric fallout and wastewater effluents [8].

- Fragments: Irregularly shaped particles resulting from the weathering and mechanical breakdown of larger plastic items such as containers, mulch films, and packaging. These are common in soils and river sediments [7].

- Films: Thin, flexible plastic sheets from degraded mulch films or plastic bags [57].

- Beads: Spherical particles, often associated with cosmetic exfoliants and industrial abrasives, though less common in rural areas unless influenced by urban runoff or direct industrial sources [57].

- Foams: Lightweight, porous plastics originating from insulation or polystyrene packaging materials [57].

2.3.5. Size Distribution and Color Variations

- Transparent and White: Typically, from packaging films and agricultural sheeting [59].

- Black and Gray: Associated with tire wear, road runoff, and industrial fragments [60].

- Blue and Green: Common from textiles, ropes, and fishing gear [60].

- Red and Orange: Indicative of consumer products and colored packaging [60].

3. Transport and Distribution

4. Microplastic Occurrence and Characteristics

4.1. Polymer Characteristics

4.2. Spatial Heterogeneity Across Compartments

- Surface soils adjacent to plastic mulch use, livestock pens, and informal dumpsites exhibit high fragment concentrations.

- River sediments act as long-term sinks for denser polymers and larger particles, with deposition patterns influenced by hydrology and land use [7].

- Groundwater systems, although less frequently monitored, have shown increasing PET and polyamide contamination, especially in areas relying on untreated wastewater discharge or sludge application [4].

- Atmospheric deposition introduces fibers and smaller particles even in remote agricultural fields, carried by wind and precipitation [8].

4.3. Ecological and Environmental Impacts

4.4. Effects on Aquatic Organisms

4.5. Soil Health and Plant Interactions

4.6. Bioaccumulation and Food Chain Concerns

4.7. Human Health Risks from Rural Exposure

5. Management and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Rural Waste Management and Plastic Reduction

5.2. Agricultural Best Practices

5.3. Wastewater Treatment Solutions in Rural Contexts

5.4. Public Awareness and Education Initiatives

5.5. Regulatory Gaps and Future Policy Directions

6. Conclusions

- Standardized rural microplastics monitoring protocols for air, water, soil, and food.

- Contextualized mitigation strategies targeting biosolids use, mulching films, and decentralized sanitation.

- Investment in rural infrastructure, including plastic waste collection and wastewater upgrades.

- Integration of rural microplastics data into national plastic reduction policies.

- Research to address knowledge gaps on the long-term human health impacts of microplastics exposure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, J.-Y.; Chia, R.W.; Veerasingam, S.; Uddin, S.; Jeon, W.-H.; Moon, H.S.; Cha, J.; Lee, J. A comprehensive review of urban microplastics pollution sources, environment and human health impacts, and regulatory efforts. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, A.R.M.T.; Hasan, M.; Sadia, M.R.; Mubin, A.N.; Ali, M.M.; Senapathi, V.; Malafaia, G. Unveiling microplastics pollution in a subtropical rural recreational lake: A novel insight. Environ. Res. 2024, 250, 118543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Wen, X.; Du, C.; Jiang, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Q. Comparison of the abundance of microplastics between rural and urban areas. Chemosphere 2020, 244, 125486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, E.; Kim, Y.I.; Lee, J.Y.; Raza, M. Microplastics contamination in groundwater of rural area, eastern part of Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 895, 165006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisling, C.; Harris, R.D.; Blaze, J.; Coffin, J.; Byers, J.E. Low concentrations and low spatial variability of marine microplastics in oysters (Crassostrea virginica) in a rural Georgia estuary. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 150, 110672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibes, P.M.; Gabel, F. Floating microplastics debris in a rural river in Germany: Distribution, types and potential sources and sinks. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matjašič, T.; Mori, N.; Hostnik, I.; Bajt, O.; Viršek, M.K. Microplastics pollution in small rivers along rural–urban gradients. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 160043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, B.; Paterson, A.M.; Yao, H.; McConnell, C.; Aherne, J. The fate of microplastics in rural headwater lake catchments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 16570–16577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Nan, B.; Craig, N.J.; Pettigrove, V. Temporal and spatial variations of microplastics in roadside dust from rural and urban Victoria, Australia. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Peng, M.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, L. Significant effects of rural wastewater treatment plants in reducing microplastics pollution: A perspective from China’s southwest area. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Luo, H.; Zou, J.; Chen, J.; Pan, X.; Rousseau, D.P.; Li, J. Characteristics and removal of microplastics in rural domestic wastewater treatment facilities of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yin, L.; Wen, X.; Xiao, R.; Du, L.; Yan, S. Microplastics removal and characteristics of constructed wetlands WWTPs in rural area of Changsha, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patidar, K.; Ambade, B.; Verma, S.K.; Mohammad, F. Microplastics contamination in water and sediments of Mahanadi River, India. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo, J.F.; López-Ordaz, A.; Hernández, A.J.; Gómez, F.B.; Sabino, M.A.; Ramos, R. Rural village as a source of microplastics pollution in a riverine and marine ecosystem of the southern Venezuelan Caribbean. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2025, 269, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.; Mayer, K.; Gore, B.; Gaesser, M.; Ferguson, N. Microplastic burden in native (Cambarus appalachiensis) and non-native (Faxonius cristavarius) crayfish along semi-rural and urban streams in southwest Virginia, USA. Environ. Res. 2024, 258, 119494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, A.; Saha, G. Microplastics in our waters: Insights from a configurative systematic review of water bodies and drinking water sources. Microplastics 2025, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, C. Plastics Are Showing Up in the World’s Most Remote Places, Including Mount Everest. Science News. 20 November 2020. Available online: https://www.sciencenews.org/article/plastics-remote-places-microplastics-earth-mount-everest (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Saha, G.; Saha, S.C. Tiny particles, big problems: The threat of microplastics to marine life and human health. Processes 2024, 12, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nield, D. Microplastics Invade Ancient Rock, and that’s a Big Problem for Age Markers. Environment, Science Alert. 2024. Available online: https://www.sciencealert.com/microplastics-invade-ancient-rock-and-thats-a-big-problem-for-age-markers (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Mirande, C.; Mandin, C.; Guerrouache, M.; Langlois, V.; Tassin, B. Synthetic fibers in atmospheric fallout: A source of microplastics in the environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 104, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangeliou, N.; Grythe, H.; Klimont, Z.; Heyes, C.; Eckhardt, S.; Lopez-Aparicio, S.; Jakobs, H.; Stohl, A. Atmospheric transport is a major pathway of microplastics to remote regions. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongil-Manso, J.; Jiménez-Ballesta, R.; Trujillo-González, J.M.; San José Wery, A.; Díez Méndez, A. A comprehensive review of plastics in agricultural soils: A case study of Castilla y León (Spain) farmlands. Land 2023, 12, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.K.; He, W.Q.; Yan, C.R. ‘White revolution’ to ‘white pollution’—Agricultural plastic film mulch in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 091001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, P.L. Degradation of microplastics in the environment. In Handbook of Microplastics in the Environment; Rocha-Santos, T., Costa, M., Mouneyrac, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, F.; Meza, P.; Eguiluz, R.; Casado, F.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Geissen, V. Evidence of microplastics accumulation in agricultural soils from sewage sludge disposal. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Lu, S.; Song, Y.; Lei, L.; Hu, J.; Lv, W.; Zhou, W.; Cao, C.; Shi, H.; Yang, X.; et al. Microplastics and mesoplastic pollution in farmland soils in suburbs of Shanghai, China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, K.Z.; Forsythe, K.R.; Wang, X.; Arredondo-Navarro, A.; Tipling, G.; Jones, J.; Mata, M.; Hughes, V.; Martin, C.; Doyle, J.; et al. Emerging investigator series: Open dumping and burning: An overlooked source of terrestrial microplastics in underserved communities. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2025, 27, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lwanga, E.H.; Beriot, N.; Corradini, F.; Silva, V.; Yang, X.; Baartman, J.; Rezaei, M.; van Schaik, L.; Riksen, M.; Geissen, V. Review of microplastics sources, transport pathways and correlations with other soil stressors: A journey from agricultural sites into the environment. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellasi, A.; Binda, G.; Pozzi, A.; Galafassi, S.; Volta, P.; Bettinetti, R. Microplastics contamination in freshwater environments: A review, focusing on interactions with sediments and benthic organisms. Environments 2020, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, P.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Corradini, F.; Geissen, V. Sewage sludge application as a vehicle for microplastics in eastern Spanish agricultural soils. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 261, 114198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, R.R.W.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, H.; Jang, J. Microplastics pollution in soil and groundwater: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, V.-H.; Nguyen, M.-K.; Hoang, T.-D.; Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Lin, C.; Pham, M.-T.; Ha, M.-C.; Nguyen, T.-P.; Shaaban, M.; Chang, S.W.; et al. Microplastics characteristics, transport, risks, and remediation in groundwater: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2025, 23, 961–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezina, A.; Yakushev, E.; Savchuk, O.; Vogelsang, C.; Staalstrom, A. Modelling the influence from biota and organic matter on the transport dynamics of microplastics in the water column and bottom sediments in the Oslo Fjord. Water 2021, 13, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazne, M.; Mermillod-Blondin, F.; Vallier, M.; Hervant, F.; Dumet, A.; Nel, H.A.; Kukkola, A.; Krause, S.; Simon, L. Microplastics in freshwater sediments impact the role of a main bioturbator in ecosystem functioning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 3042–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baensch-Baltruschat, B.; Kocher, B.; Stock, F.; Reifferscheid, G. Tyre and road wear particles (TRWP): A review of generation, properties, emissions, human health risk, ecotoxicity, and fate in the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 733, 137823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir, S.M.A.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Zhang, G.; Pramanik, B.K. Microplastics distribution and ecological risks: Investigating road dust and stormwater runoff across land uses. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2024, 3, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCBC: The Nature Conservancy & Bain & Company. Toward Eliminating Pre-Consumer Emissions of Microplastics from the Textile Industry [White Paper]. The Nature Conservancy. Available online: https://www.nature.org/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/210322TNCBain_Pre-ConsumerMicrofiberEmissionsv6.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Browne, M.A.; Crump, P.; Niven, S.J.; Teuten, E.; Tonkin, A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R. Accumulation of microplastics on shorelines worldwide: Sources and sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9175–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blettler, M.C.M.; Ulla, M.A.; Rabuffetti, A.P.; Garello, N. Plastic pollution in freshwater ecosystems: Macro-, meso-, and microplastics debris in a floodplain lake. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, F. Microplastics Transport by Overland Flow: Effects of Soil Texture and Slope Gradient under Simulated Semi-Arid Conditions. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owowenu, E.K.; Nnadozie, C.F.; Akamagwuna, F.; Noundou, X.S.; Uku, J.E.; Odume, O.N. A critical review of environmental factors influencing the transport dynamics of microplastics in riverine systems: Implications for ecological studies. Aquat. Ecol. 2023, 57, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, T.; Gönczy, S.; Nagy, T.; Mesaroš, M.; Balla, A. Deposition and Mobilization of Microplastics in a Low-Energy Fluvial Environment from a Geomorphological Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefer, R.B.; Koestel, J.; Mitrano, D.M. Minimal vertical transport of microplastics in soil over two years with little impact of plastics on soil macropore networks. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.; Pan, S.; Shen, Z.; Song, Y.; Jin, Y.; Wu, W.-M.; Hou, D. Microplastics undergo accelerated vertical migration in sand soil due to small size and wet–dry cycles. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, X.; Wang, S.; Zheng, B.; Xu, Y. Vertical migration of microplastics along soil profile under different crop root systems. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 278, 116833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, C.; Kim, H. Microplastics and nanoplastics in groundwater: Occurrence, analysis, and identification. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2024, 44, e00246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Baladima, F.; Phoenix, V.R.; Thomas, J.L.; Le Roux, G.; Sonke, J.E. Evidence of free-tropospheric and long-range transport of microplastics at Pic du Midi Observatory. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, X.; Zhang, S.; Huang, D.; Chang, C.; Peng, C.; Liu, K.; Fu, T.M.; Han, Y.; Liu, X.; Fu, T.-M.; et al. Atmospheric microplastics emission source potentials and deposition patterns in semi-arid croplands of northern China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2024JD041546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Ren, S.; Huang, D.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, M.; Cao, Y.; Mofolo, S.; et al. Atmospheric deposition of microplastics in a rural region of the North China Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rednikin, A.R.; Frank, Y.A.; Rozhin, A.O.; Vorobiev, D.S.; Fakhrullin, R.F. Airborne microplastics: Challenges, prospects, and experimental approaches. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Saha, S.C.; Saha, G.; Francis, I.; Luo, Z. Transport and deposition of microplastics and nanoplastics in the human respiratory tract. Environ. Adv. 2024, 16, 100525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boos, J.-P.; Dichgans, F.; Fleckenstein, J.H.; Gilfedder, B.S.; Frei, S. Assessing the behavior of microplastics in fluvial systems: Infiltration and retention dynamics in streambed sediments. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, D.; Ndlovu, M.; Ramaremisa, G.; Tutu, H.; Sillanpää, M. Characteristics of microplastics in sediment of the Vaal River, South Africa: Implications on bioavailability and toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Cheng, J.; Ji, R.; Ma, Y.; Yu, X. Microplastics in agricultural soils: Sources, effects, and their fate. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2022, 25, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Holsen, T.M.; Baki, A.B.M. Distribution and risk assessment of microplastics pollution in a rural river system near a wastewater treatment plant, hydro-dam, and river confluence. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stride, B.; Abolfathi, S.; Bending, G.D.; Pearson, J. Quantifying microplastics dispersion due to density effects. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 466, 133440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, L.; Liu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Wu, W.; Gao, Y.; Ling, W. Sources of microplastics in the environment. In Microplastics in Terrestrial Environments—Emerging Contaminants and Major Challenges; He, D., Luo, Y., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.J.; Opp, C.; Prume, J.A.; Koch, M.; Chifflard, P. Meso- and microplastics distribution and spatial connections to metal contaminations in highly cultivated and urbanised floodplain soilscapes—A case study from the Nidda River (Germany). Microplast. Nanoplast. 2022, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Huo, T. The distribution of microplastics pollution and ecological risk assessment of Jingpo Lake—The world’s second largest high-mountain barrier lake. Biology 2025, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.T.; Diamond, M.L.; Helm, P.A. A fit-for-purpose categorization scheme for microplastics morphologies. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2023, 19, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, Y.; Mitsunaga, K.; Yamaji, K.; Hirokawa, S.; Uaciquete, D.; Ríos, J.M.; Yap, C.K.; Okamura, H. Variability in microplastics color preference and intake among selected marine and freshwater fish and crustaceans. Discov. Ocean. 2024, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, E.C.; Viršek, M.K.; Mali, N. Microplastics in groundwater: Pathways, occurrence, and monitoring challenges. Water 2024, 16, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda, A.C.; Blasina, G.; Renaud, L.C.; Menéndez, M.C.; Tomba, J.P.; Silva, L.I.; Arias, A.H. Effects of microplastic ingestion on feeding activity in a widespread fish on the southwestern Atlantic coast: Ramnogaster arcuata (Clupeidae). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-Y.; Shu, Y.-Q.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.-L.; Wu, Z.-H.; Li, Z.-P.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, Z.-J.; Zhang, X.-J.; Gong, L.-F.; et al. Metabolic disruption exacerbates intestinal damage during sleep deprivation by abolishing HIF1α-mediated repair. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Machado, A.A.; Lau, C.W.; Till, J.; Kloas, W.; Lehmann, A.; Becker, R.; Rillig, M.C. Impacts of microplastics on the soil biophysical environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9656–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, Y.; An, Y.J. Current research trends on plastic pollution and ecological impacts on the soil ecosystem: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 240, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbachu, O.; Jenkins, G.; Kaparaju, P.; Pratt, C. The rise of artificial soil carbon inputs: Reviewing microplastic pollution effects in the soil environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 780, 146569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlers, S.; Manz, W.; Koop, J. Microplastics of different characteristics are incorporated into the larval cases of the freshwater caddisfly Lepidostoma basale. Aquat. Biol. 2019, 28, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, A.; Saha, G.; Saha, S.C. Microplastics in animals: The silent invasion. Pollutants 2024, 4, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, J.; Hurley, R.R.; Futter, M.; Nizzetto, L. Transfer and transport of microplastics from biosolids to agricultural soils and the wider environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 138334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Muhammad, M.; Chen, X.; Lu, C.; Wang, X.; Dong, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Liang, L.; et al. Modulation of soil microenvironment and plant gene expression by earthworms reduces polypropylene microplastic-induced growth stress in Chinese milk vetch (Astragalus sinicus L.). Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2025, 7, 2080–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J. Earthworms Help Revive Plants in Plastic-Polluted Soil. Earth.com. Available online: https://www.earth.com/news/earthworms-help-revive-plants-in-plastic-polluted-soil/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Lusher, A.L.; Welden, N.A.; Sobral, P.; Cole, M. Sampling, isolating and identifying microplastics ingested by fish and invertebrates. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1346–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Lopes, I.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental exposure to microplastics: An overview on possible human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Z.; Wu, H.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Airborne micro- and nanoplastics: Emerging causes of respiratory diseases. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2024, 21, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.C.; Saha, G. Effect of microplastics deposition on human lung airways: A review with computational benefits and challenges. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, G.; Nichter, M.; Hardon, A.; Moyer, E.; Latkar, A.; Simbaya, J.; Pakasi, D.; Taqueban, E.; Love, J. Plastic pollution and the open burning of plastic wastes: Ethnographic perspectives from underserved communities. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 80, 102648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Ingraffia, R.; de Souza Machado, A.A. Microplastics incorporation into soil in agro-ecosystems. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Chao, J.; Teng, J.; Wang, Q. Microplastics in soils: A review of possible sources, analytical methods and ecological impacts. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 2052–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Galafassi, S.; Di Pippo, F.; Pojar, I.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. A critical review of biodegradable plastic mulch films in agriculture: Definitions, scientific background and potential impacts. Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 170, 117391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shen, C.; Zhang, F.; Wei, K.; Shan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Man, Y.B.; Wong, M.H.; Zhang, J. Microplastics removal mechanisms in constructed wetlands and their impacts on nutrient (nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon) removal: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 170654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premarathna, K.; Abeysundara, S.P.; Gunaratne, A.M.T.A.; Madawala, H.M.S.P. Community awareness and perceptions on microplastics: A case study from Sri Lanka. Ceylon J. Sci. 2023, 52, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, Z.; Zarei, F.; Ahmadi, F. The effect of an educational intervention based on a mobile application on women’s knowledge, attitudes, and practices with respect to microplastics and health: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belontz, S.L.; Corcoran, P.L.; Davis, H.; Hill, K.A.; Jazvac, K.; Robertson, K.; Wood, K. Embracing an interdisciplinary approach to plastics pollution awareness and action. Ambio 2019, 48, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Common Forms/Types | Dominant Sources | Representative Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers | PE, PP, PET, PS, PVC | Agricultural mulch, textiles, packaging, wastewater | [4,25,55] |

| Physical Forms | Fragments, Fibers, Films, Beads, Foams | Degraded waste, textiles, fishing gear, mulch films | [7,8] |

| Size Distribution | <100 µm to 5 mm | Plastic breakdown, atmospheric fallout, wastewater | [2,4] |

| Color Variability | Clear, Blue, Black, White, Red | Ropes, packaging, tire wear, textiles | [2,7] |

| Impact Area | Observed Effect | Key Study |

|---|---|---|

| Aquatic Fauna | Gastrointestinal blockage, pollutant exposure | [15] |

| Soil Health | Altered porosity, microbial disruption, enzyme inhibition | [26] |

| Food Chain Transfer | MP ingestion in shellfish and transfer up trophic levels | [5] |

| Human Health | Contamination in drinking water, inflammatory potential | [4] |

| Focus Area | Intervention | Key Study |

|---|---|---|

| Waste Management | Decentralized recycling, enforcement of open dumping bans | [14] |

| Agriculture | Biodegradable mulches, sludge standards, collection systems | [25] |

| Wastewater Treatment | Constructed wetlands, sedimentation tanks, filtration | [10] |

| Public Awareness | Local education, community waste audits, school outreach | [9] |

| Policy and Regulation | Take-back programs, rural MP monitoring | [72] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bhowmik, A.; Saha, G. Microplastics in the Rural Environment: Sources, Transport, and Impacts. Pollutants 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants6010003

Bhowmik A, Saha G. Microplastics in the Rural Environment: Sources, Transport, and Impacts. Pollutants. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhowmik, Awnon, and Goutam Saha. 2026. "Microplastics in the Rural Environment: Sources, Transport, and Impacts" Pollutants 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants6010003

APA StyleBhowmik, A., & Saha, G. (2026). Microplastics in the Rural Environment: Sources, Transport, and Impacts. Pollutants, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants6010003