Actinomycetes-Mediated Decomposition of Chicken Feathers: Effects on Nitrogen Recovery over Time

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

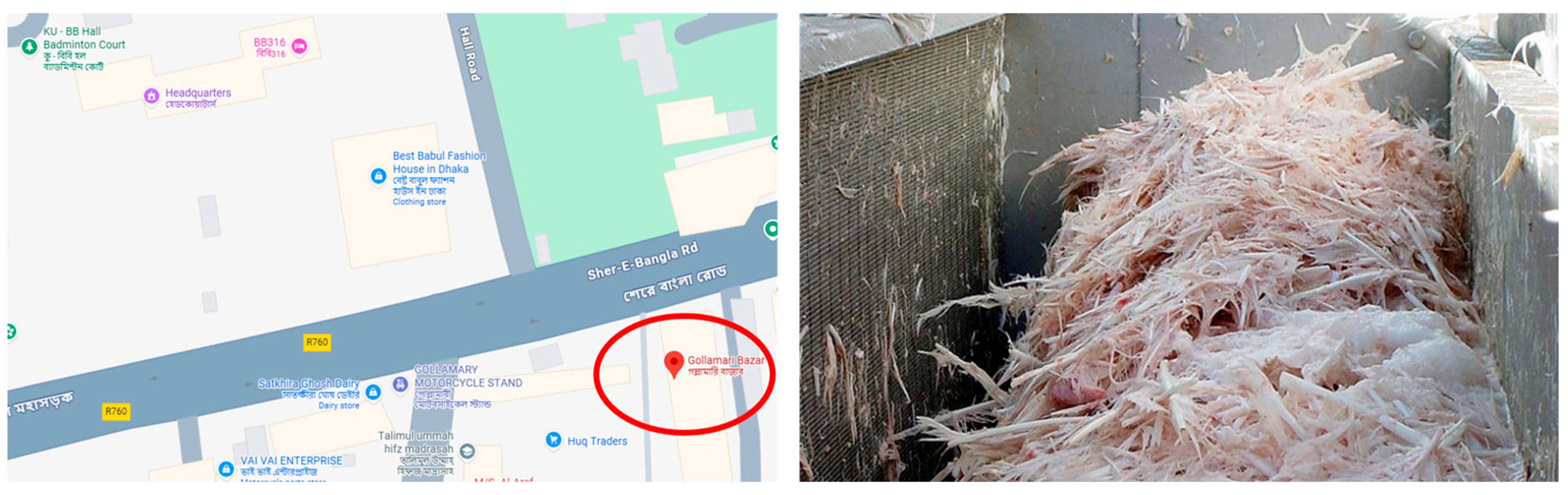

2.1. Sample (Chicken Feathers) Collection and Processing

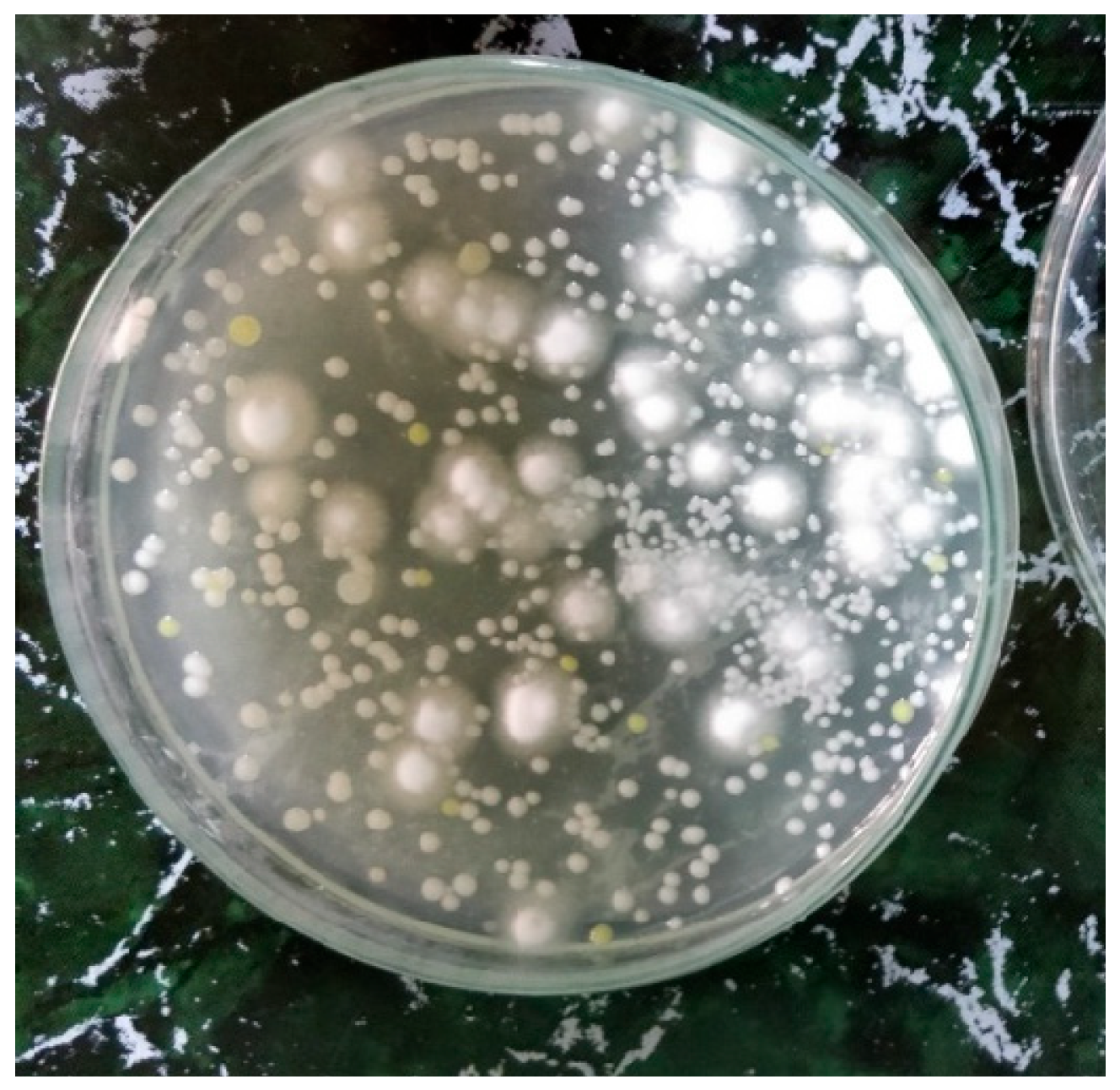

2.2. Isolation of Bacteria

2.3. Culture Media Preparation for Microbial Growth

2.4. Identification of Bacteria

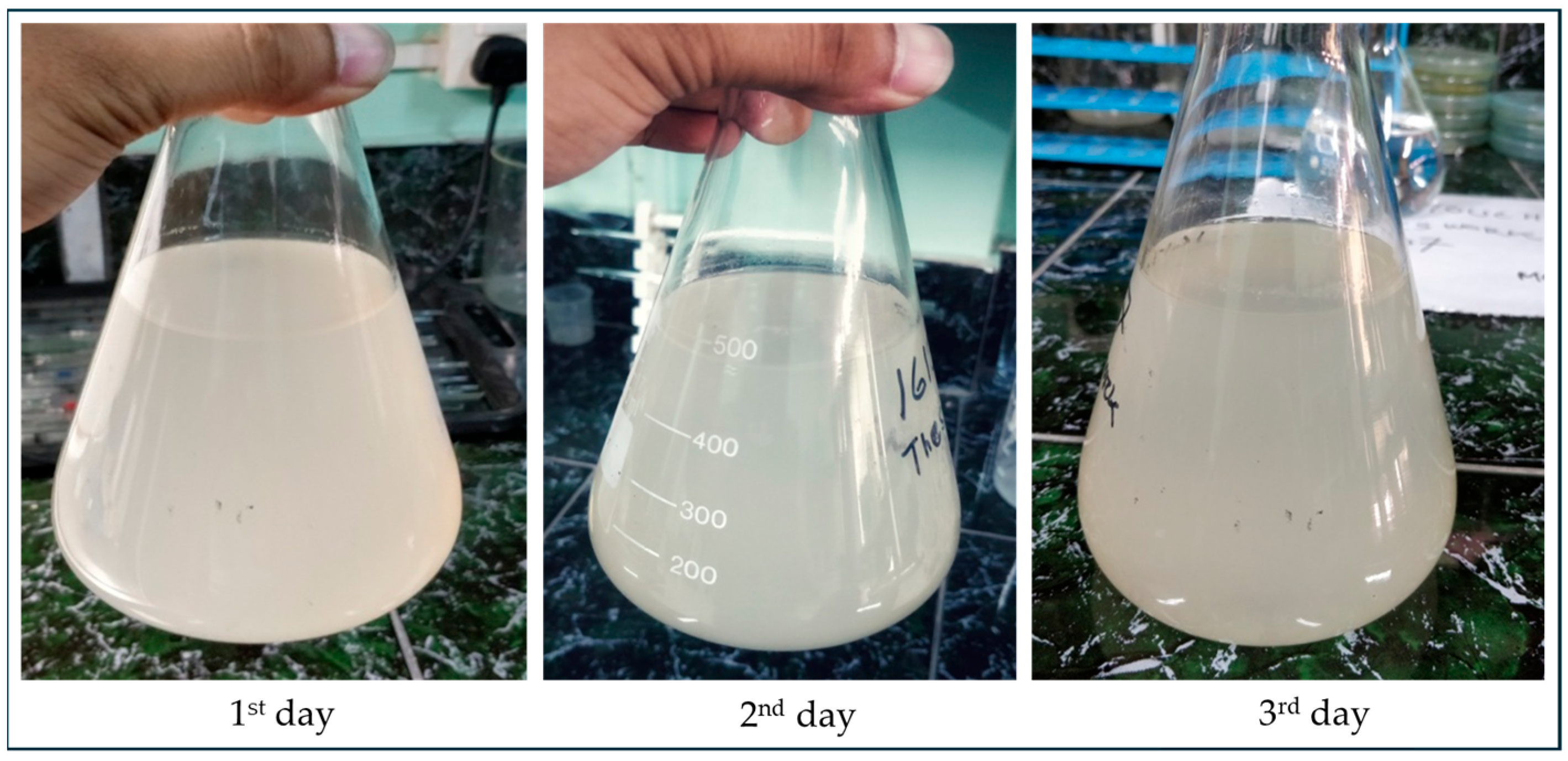

2.5. Experimental Setup and Procedures

2.6. Estimation of Nitrogen

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Experiment Outcomes

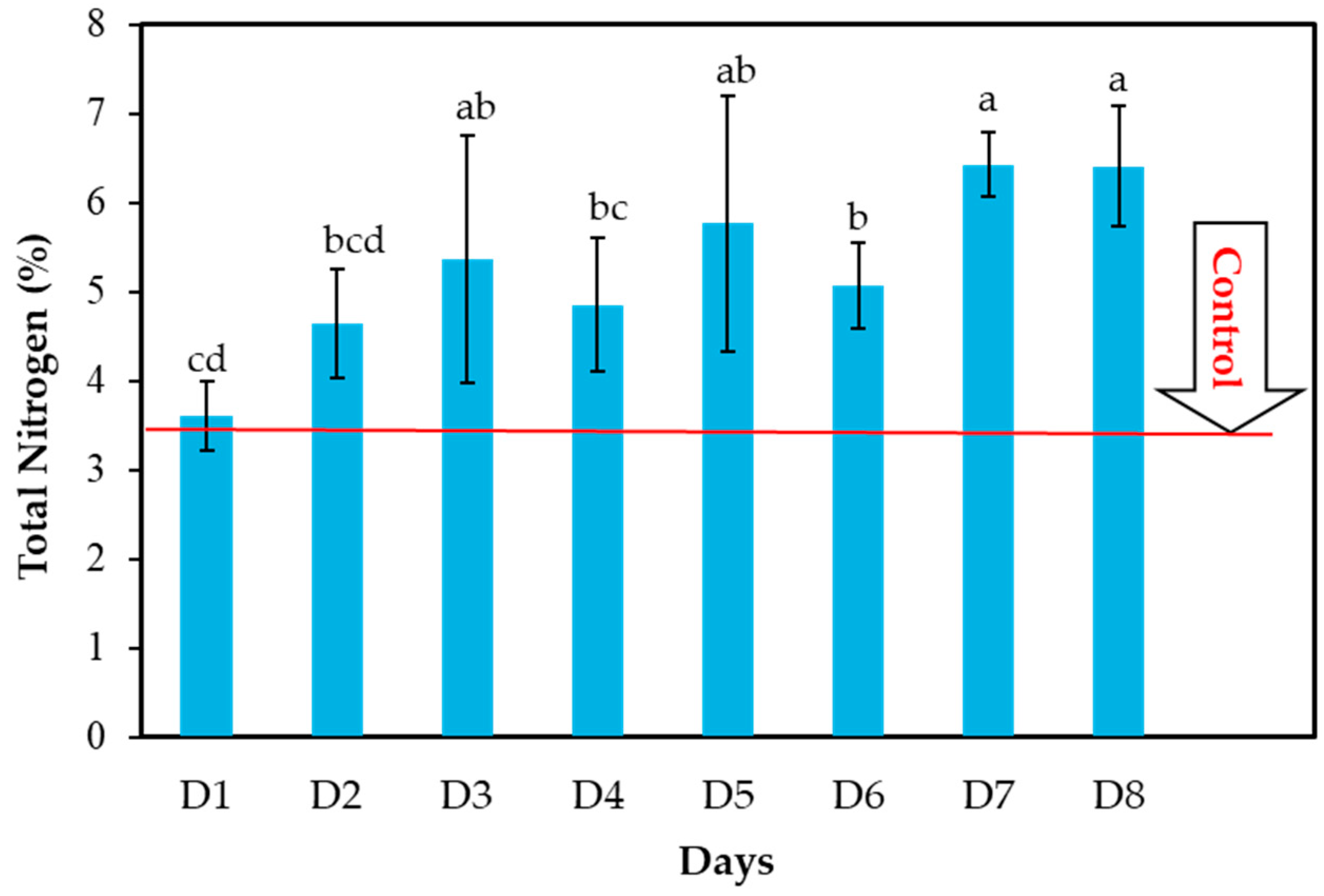

3.1. Effects of Composting Time on Total N (%) Content in CFW Compost

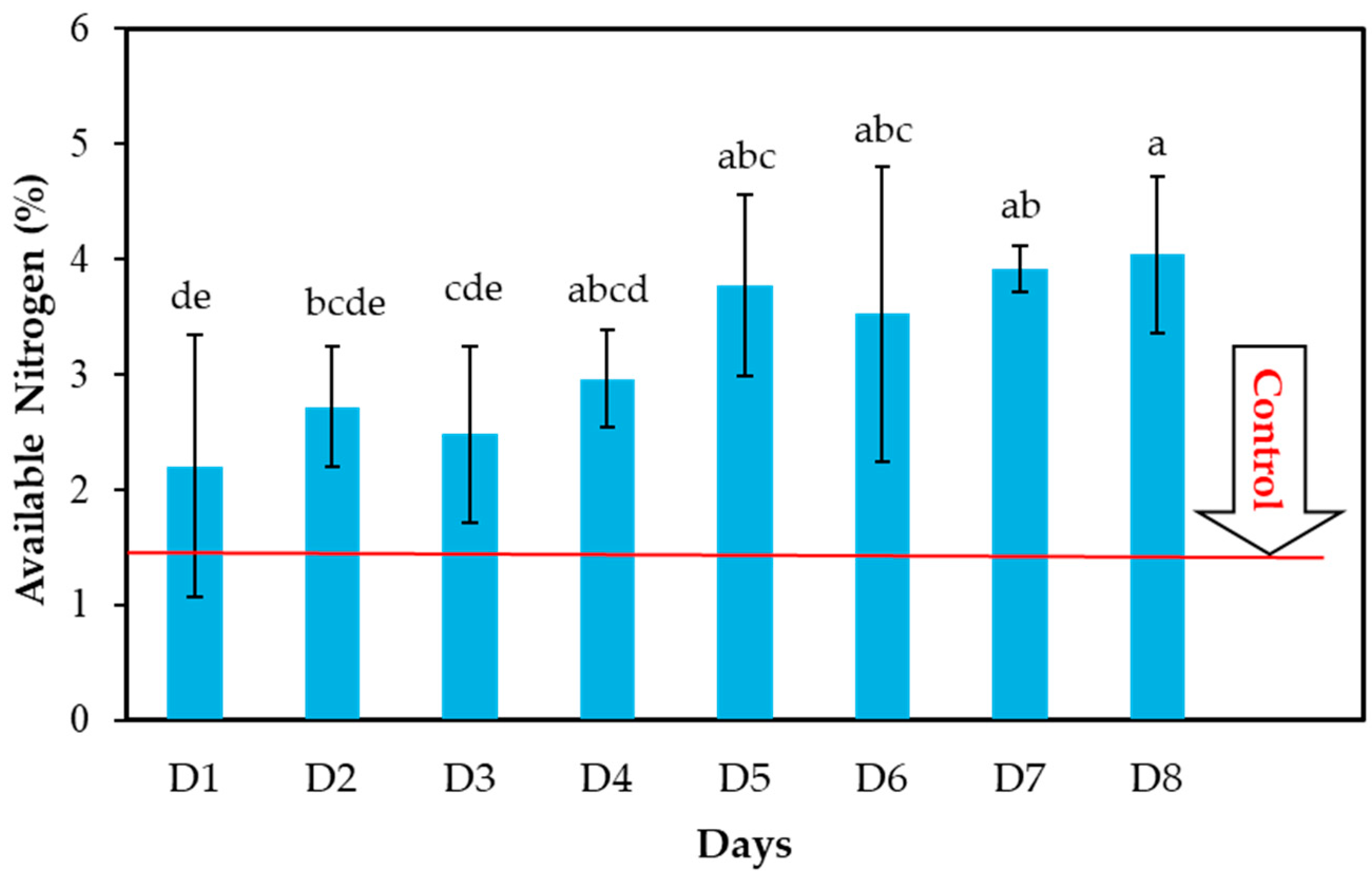

3.2. Effects of Composting Time on Available N (%) Content in CFW Compost

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bakari, R.; Asha, R.; Hossein, M.; Huang, X.; Islam, N.; Liew, R.K.; Narayan, M.; Lam, S.S.; Sarma, H. Converting Food Waste to Biofuel: A Sustainable Energy Solution for Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 7, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.J.; Begum, I.A.; Al Mamun, A.; Iqbal, A.; McKenzie, A.M. The adoption of biosecurity measures and its influencing factors in Bangladeshi layer farms. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, T.; Gibson, J.S.; Foysal, M.; Das, S.B.; Das Gupta, S.; Fournié, G.; Hoque, A.; Henning, J. A Cross-Sectional Study of Antimicrobial Usage on Commercial Broiler and Layer Chicken Farms in Bangladesh. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 576113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidavi, A.R.; Zaker-Esteghamati, H.; Scanes, C.G. Chicken processing: Impact, co-products and potential. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2019, 75, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppannan, S.K.; Dowlath, M.J.H.; Raiyaan, G.D.; Rajadesingu, S.; Arunachalam, K.D. Application of poultry industry waste in producing value-added products—A review. In Concepts of Advanced Zero Waste Tools; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 91–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Sharma, S.; Aich, A.; Verma, A.K.; Bhuyar, P.; Nadda, A.K.; Mulla, S.I.; Kalia, S. Chicken Feather Waste Hydrolysate as a Potential Biofertilizer for Environmental Sustainability in Organic Agriculture Management. Waste Biomass Valori. 2023, 14, 2783–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzinic, G.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.; Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A.; Górny, R.L.; Ławniczek-Wałczyk, A.; Piechowicz, L.; Olkowska, E.; Potrykus, M.; Tankiewicz, M.; Krupka, M.; et al. Intensive poultry farming: A review of the impact on the environment and human health. Sci. Total Environ 2023, 858 Pt 3, 160014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesús, M.; Álvarez, M.D.; Garrido, N.; Molins, G.; Macanás, J.; Colom, X.; Cañavate, J.; Carrillo, F. Environmental impact assessment of sound absorbing nonwovens based on chicken feathers waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradoaei, S.; Constantin, M.A.; Constantin, L.A.; Aradoaei, M.; Ciobanu, R.C. A Sustainability Study upon Manufacturing Thermoplastic Building Materials by Integrating Chicken Feather Fibers with Plastic Waste. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Hassan, A.; Hossain, I.; Jahangir, M.; Chowdhury, E.; Parvin, R. Current state of poultry waste management practices in Bangladesh, environmental concerns, and future recommendations. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2022, 9, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferro, V.R.; Leiva, H.; Cadena, E.; Valverde, J.L. Multiscale Conceptual Design of a Scalable and Sustainable Process to Dissolve and Regenerate Keratin from Chicken Feathers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 13324–13339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, B.; Khatri, M.; Singh, G.; Arya, S.K. Microbial keratinases: An overview of biochemical characterization and its eco-friendly approach for industrial applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhari, R.; Kaur, M.; Sarup Singh, R. Chicken Feather Waste Hydrolysate as a Superior Biofertilizer in Agroindustry. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 2212–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, T.; Leceta, I.; de la Caba, K.; Guerrero, P. Chicken feathers as a natural source of sulphur to develop sustainable protein films with enhanced properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Wilkens, C.; Barrett, K.; Meyer, A.S. Microbial enzymes catalyzing keratin degradation: Classification, structure, function. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 44, 107607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Călin, M.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D.; Alexandrescu, E.; Răut, I.; Doni, M.B.; Arsene, M.-L.; Oancea, F.; Jecu, L.; Lazăr, V. Degradation of keratin substrates by keratinolytic fungi. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 28, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Perspectives on Converting Keratin-Containing Wastes Into Biofertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 918262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavandi, A.; Silva, T.H.; Bekhit, A.A.; Bekhit, A.E.-D.A. Keratin: Dissolution, extraction and biomedical application. Biomater. Sci. 2017, 5, 1699–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilakamarry, C.R.; Mahmood, S.; Saffe, S.N.B.M.; Bin Arifin, M.A.; Gupta, A.; Sikkandar, M.Y.; Begum, S.S.; Narasaiah, B. Extraction and application of keratin from natural resources: A review. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbesaw, M.S. Bioconversion of Keratin Wastes Using Keratinolytic Microorganisms to Generate Value-Added Products. Int. J. Biomater. 2022, 2022, 2048031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelere, I.A.; Lateef, A. Degradation of keratin biomass by different microorganisms. In Keratin as a Protein Biopolymer: Extraction from Waste Biomass and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 123–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sypka, M.; Jodlowska, I.; Bialkowska, A.M. Keratinases as Versatile Enzymatic Tools for Sustainable Development. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Elhoul, M.; Jaouadi, N.Z.; Rekik, H.; Benmrad, M.O.; Mechri, S.; Moujehed, E.; Kourdali, S.; El Hattab, M.; Badis, A.; Bejar, S.; et al. Biochemical and molecular characterization of new keratinoytic protease from Actinomadura viridilutea DZ50. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 92, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatova, Z.; Gousterova, A.; Spassov, G.; Nedkov, P. Isolation and partial characterisation of extracellular keratinase from a wool degrading thermophilic actinomycete strain Thermoactinomyces candidus. Can. J. Microbiol. 1999, 45, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, D.; Nawani, N.; Prakash, M.; Bodas, M.; Mandal, A.; Khetmalas, M.; Kapadnis, B. Actinomycetes: A repertory of green catalysts with a potential revenue resource. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 264020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subash, H.A.; Santhosh, K.; Kannan, K.; Pitchiah, S. Extraction of Keratin degrading enzyme from marine Actinobacteria of Nocardia sp and their antibacterial potential against oral pathogens. Oral. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 9, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnovic, S.; Aleksic, I.; Ilic-Tomic, T.; Stevanovic, M.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J. Bacillus and Streptomyces spp. as hosts for production of industrially relevant enzymes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamma, S.; Boucherba, N.; Azzouz, Z.; Le Roes-Hill, M.; Kernou, O.-N.; Bettache, A.; Ladjouzi, R.; Maibeche, R.; Benhoula, M.; Hebal, H.; et al. Statistical Optimisation of sp. DZ 06 Keratinase Production by Submerged Fermentation of Chicken Feather Meal. Fermentation 2024, 10, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Keratanophilic Fungi. Res. J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 16, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, S.A.; Khalel, A.F.; Alghamdi, M.A.; Alshehri, W.A.; Alsubeihi, G.K.; Alsolmy, S.A.; Hakeem, M.A. Isolation, Identification and Characterization of Keratin-Degrading AM8. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 16, 2045–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-W.; Liang, S.; Ke, Y.; Deng, J.-J.; Zhang, M.-S.; Lu, D.-L.; Li, J.-Z.; Luo, X.-C. The feather degradation mechanisms of a new Streptomyces sp. isolate SCUT-3. Commun Biol 2020, 3, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farda, B.; Djebaili, R.; Vaccarelli, I.; Del Gallo, M.; Pellegrini, M. Actinomycetes from Caves: An Overview of Their Diversity, Biotechnological Properties, and Insights for Their Use in Soil Environments. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.A.; Islam, M.Z.; Islam, M.A. Antibacterial activities of actinomycete isolates collected from soils of rajshahi, bangladesh. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 857925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albasri, H.M.; Almohammadi, M.S.; Mawad, A.M. Biological Activity and Enzymatic Productivity of Two Thermophilic Actinomycetes Isolated from the Uhud Mountain. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2024, 22, 3975–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joardar, J.; Rahman, M. Poultry feather waste management and effects on plant growth. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2018, 7, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Gupta, A. Sustainable Management of Keratin Waste Biomass: Applications and Future Perspectives. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2016, 59, e16150684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Salamony, D.H.; Hassouna, M.S.E.; Zaghloul, T.I.; He, Z.; Abdallah, H.M. Bioenergy production from chicken feather waste by anaerobic digestion and bioelectrochemical systems. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, H.; Kumar, U.; Mariappan, S.; Mishra, A.P.; Kumar, S. Impact of organic and inorganic farming on soil quality and crop productivity for agricultural fields: A comparative assessment. Environ. Chall. 2024, 15, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diksha, S.S.; Tyagi, T.; Chawla, G. Chapter: 8 Waste Management Strategies in Poultry Production. In Innovative Poultry Science: Trends, Disease Management, and Future Perspectives; Kavya Publications: New Delhi, India, 2024; p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, A.; Muzzamal, H.; Maqsood, B.; Naz, S.; Latif, F.; Saleem, M. Characterization of a Bacterial Keratinolytic Protease for Effective Degradation of Chicken Feather Waste into Feather Protein Hydrolysates. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2024, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, T.; Sithole, B.; Ramjugernath, D.; Mokhothu, T. Valorisation of chicken feathers: Characterisation of thermal, mechanical and electrical properties. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2018, 9, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertcanawanichakul, M.; Sahabuddeen, T. Characterization of Streptomyces sp. KB1 and its cultural optimization for bioactive compounds production. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) Official Methods of Analysis; AOAC: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 223–225. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Plaza, P.; Navas, M.J.; Wybraniec, S.; Michałowski, T.; Asuero, A.G. An overview of the Kjeldahl method of nitrogen determination. Part II. Sample preparation, working scale, instrumental finish, and quality control. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2013, 43, 224–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanotti, M.B.; García-González, M.C.; Molinuevo-Salces, B.; Riaño, B. New processes for nutrient recovery from wastes. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soobhany, N. Insight into the recovery of nutrients from organic solid waste through biochemical conversion processes for fertilizer production: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frossard, E.; Crain, G.; Bordóns, I.G.d.A.; Hirschvogel, C.; Oberson, A.; Paille, C.; Pellegri, G.; Udert, K.M. Recycling nutrients from organic waste for growing higher plants in the Micro Ecological Life Support System Alternative (MELiSSA) loop during long-term space missions. Life Sci. Space Res. 2024, 40, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, K.A.; Gomez, A.A. Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1984; p. 680. [Google Scholar]

- Mozejko, M.; Bohacz, J. Optimization of Conditions for Feather Waste Biodegradation by Geophilic Trichophyton ajelloi Fungal Strains towards Further Agricultural Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Aziz, N.M.; Khalil, B.E.; Ibrahim, H.F. Enhancement of feather degrading keratinase of Streptomyces swerraensis KN23, applying mutagenesis and statistical optimization to improve keratinase activity. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vann, M.; Bennett, N.; Fisher, L.; Reberg-Horton, S.C.; Burrack, H. Poultry Feather Meal Application in Organic Flue-Cured Tobacco Production. Agron. J. 2017, 109, 2800–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamreihao, K.; Mukherjee, S.; Khunjamayum, R.; Devi, L.J.; Asem, R.S.; Ningthoujam, D.S. Feather degradation by keratinolytic bacteria and biofertilizing potential for sustainable agricultural production. J. Basic Microbiol. 2019, 59, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobucki, L.; Ramos, R.F.; Gubiani, E.; Brunetto, G.; Kaiser, D.R.; Daroit, D.J. Feather hydrolysate as a promising nitrogen-rich fertilizer for greenhouse lettuce cultivation. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2019, 8, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenke, G. Nitrogen volatilisation: Factors affecting how much N is lost and how much is left over time. In GRDC Research Update. Accessed; GRDC: Canberra, Australia, 2014; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Bohacz, J. Changes in mineral forms of nitrogen and sulfur and enzymatic activities during composting of lignocellulosic waste and chicken feathers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 10333–10342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Li, M.; Song, L.; Wang, C.; Yang, S.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Y. Study on nitrogen-retaining microbial agent to reduce nitrogen loss during chicken manure composting and nitrogen transformation mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenakshi, S.; Hiremath, J.; Meenakshi, M.; Shivaveerakumar, S. Actinomycetes: Isolation, Cultivation and its Active Biomolecules. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 18, 118–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Progress in Microbial Degradation of Feather Waste. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ingredients | gm/0.5 L |

|---|---|

| Sodium caseinate | 1.000 |

| L-Asparagine | 0.05 |

| Sodium propionate | 2.000 |

| Dipotassium phosphate | 0.25 |

| Magnesium sulphate | 0.05 |

| Ferrous sulphate | 0.0005 |

| Agar | 7 |

| Days | Control (% N) | Treatment (% N) | % N Increase over Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 3.46 | 3.60 | 4.04 |

| D2 | 3.46 | 4.64 | 34.10 |

| D3 | 3.46 | 5.36 | 54.91 |

| D4 | 3.46 | 4.85 | 40.17 |

| D5 | 3.46 | 5.77 | 66.76 |

| D6 | 3.46 | 5.06 | 46.24 |

| D7 | 3.46 | 6.43 | 85.83 |

| D8 | 3.46 | 6.41 | 85.26 |

| Days | Control (% N) | Treatment (% N) | % N Increase over Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 1.42 | 2.21 | 55.63 |

| D2 | 1.42 | 2.72 | 91.54 |

| D3 | 1.42 | 2.48 | 74.64 |

| D4 | 1.42 | 2.96 | 108.45 |

| D5 | 1.42 | 3.77 | 165.49 |

| D6 | 1.42 | 3.52 | 147.88 |

| D7 | 1.42 | 3.91 | 175.55 |

| D8 | 1.42 | 4.04 | 184.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shimki, A.I.; Sajid, F.A.N.; Hosen, Z. Actinomycetes-Mediated Decomposition of Chicken Feathers: Effects on Nitrogen Recovery over Time. Pollutants 2025, 5, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants5040047

Shimki AI, Sajid FAN, Hosen Z. Actinomycetes-Mediated Decomposition of Chicken Feathers: Effects on Nitrogen Recovery over Time. Pollutants. 2025; 5(4):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants5040047

Chicago/Turabian StyleShimki, Afia Ibnath, Fahad Al Nur Sajid, and Zubaer Hosen. 2025. "Actinomycetes-Mediated Decomposition of Chicken Feathers: Effects on Nitrogen Recovery over Time" Pollutants 5, no. 4: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants5040047

APA StyleShimki, A. I., Sajid, F. A. N., & Hosen, Z. (2025). Actinomycetes-Mediated Decomposition of Chicken Feathers: Effects on Nitrogen Recovery over Time. Pollutants, 5(4), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants5040047