A Mini Review of Pressure-Assisted Soil Electrokinetics Remediation for Contaminant Removal, Dewatering, and Soil Improvement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Procedure for Choosing Published Works on Pressure-Assisted Soil Electrokinetics

3. Pressure-Assisted Soil Electrokinetics

3.1. Removal of Inorganic Pollutants

3.2. Dewatering (Dryness Based on Electroosmotic Flow) Using Electrokinetics with the Pressure Assistance Technique

3.2.1. Case Studies

3.2.2. Facts and Conclusions

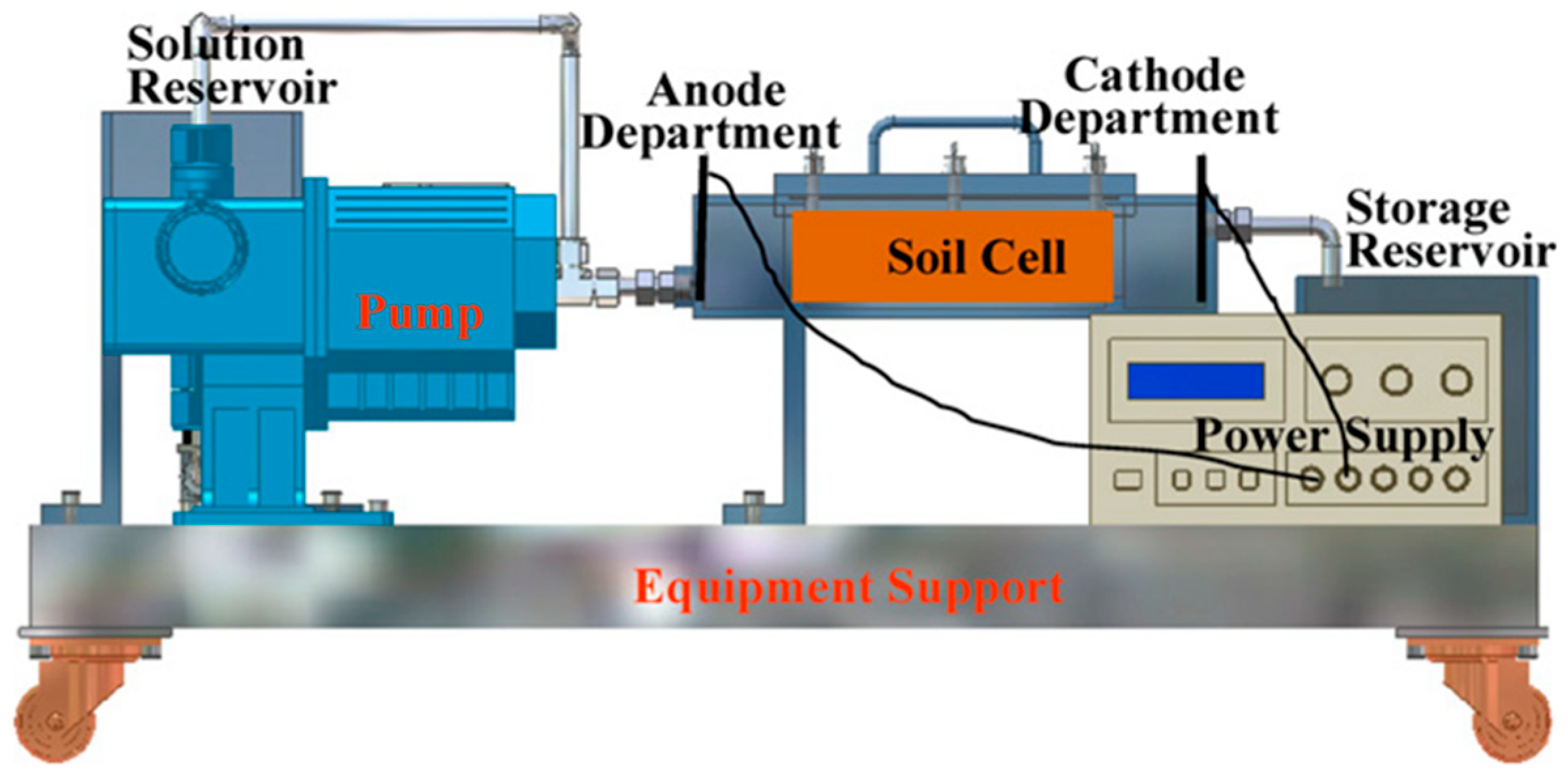

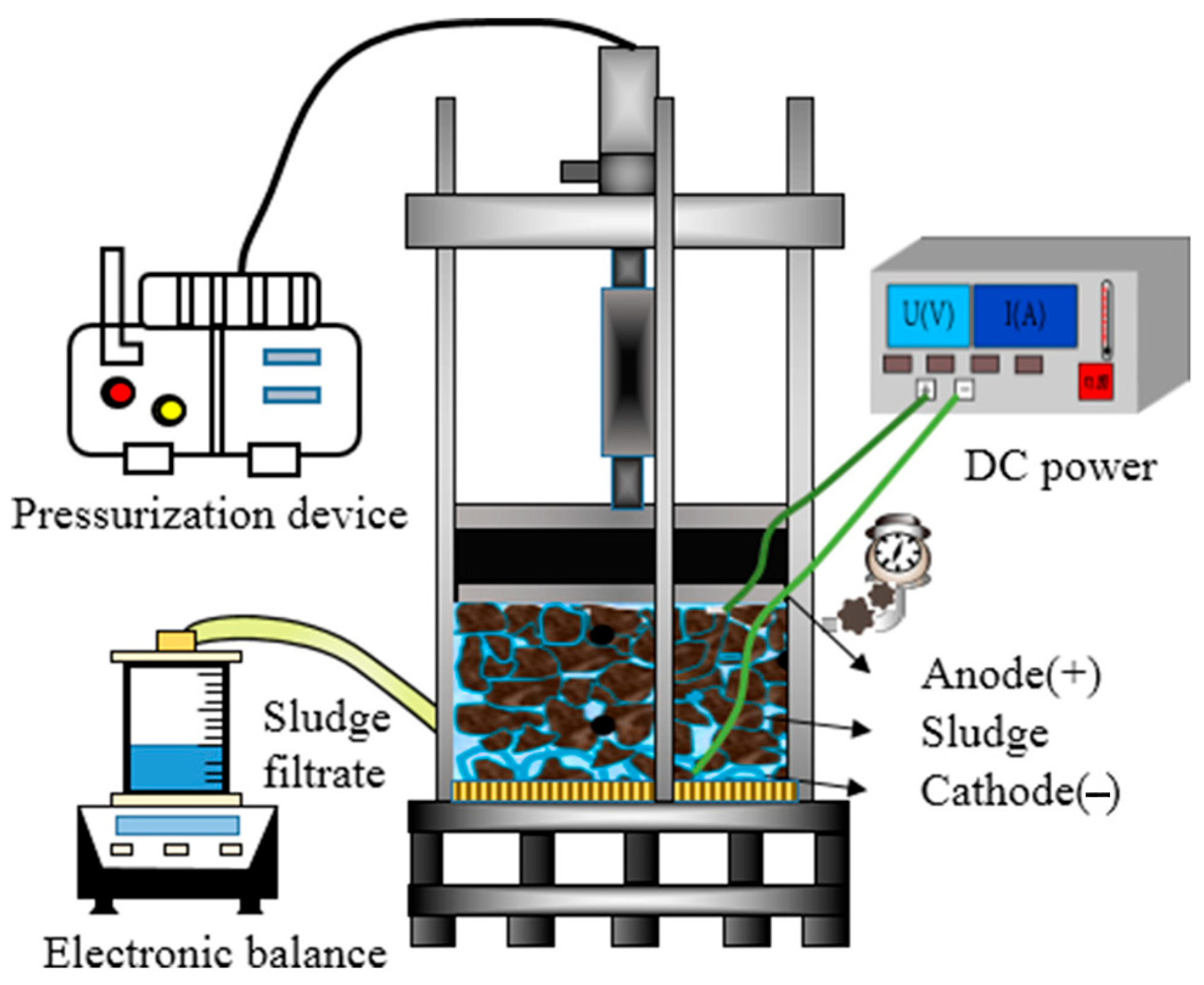

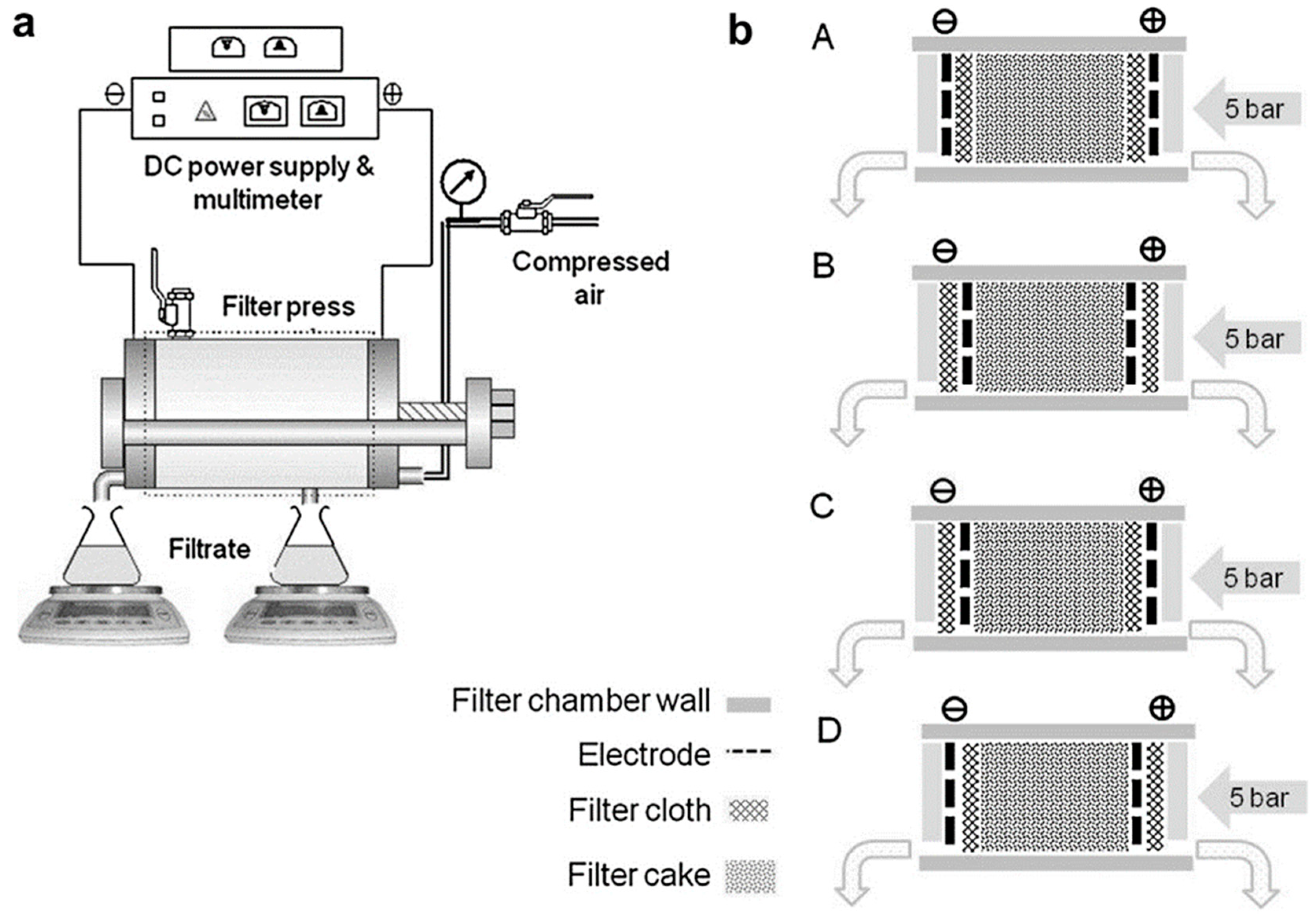

3.2.3. Design of Electrokinetic Equipment

3.3. Soil Improvement (Rehabilitation) via Pressure-Assisted Electrokinetic

3.4. Making Soil Ready for Electrokinetic Action by Applying Pressure

4. Future Research on the Use of Pressure-Assisted Soil Electrokinetics Remediation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abou-Shady, A.; Ali, M.E.A.; Ismail, S.; Abd-Elmottaleb, O.; Kotp, Y.H.; Osman, M.A.; Hegab, R.H.; Habib, A.A.M.; Saudi, A.M.; Eissa, D.; et al. Comprehensive review of progress made in soil electrokinetic research during 1993–2020, Part I: Process design modifications with brief summaries of main output. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 44, 156–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; Ismail, S.; Yossif, T.M.H.; Yassin, S.A.; Ali, M.E.A.; Habib, A.A.M.; Khalil, A.K.A.; Tag-Elden, M.A.; Emam, T.M.; Mahmoud, A.A.; et al. Comprehensive review of progress made in soil electrokinetic research during 1993–2020, part II. No.1: Materials additives for enhancing the intensification process during 2017–2020. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 45, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.K.; Ottosen, L.M.; Ribeiro, A.B. Electrokinetic Soil Remediation: An Overview BT. In Electrokinetics Across Disciplines and Continents: New Strategies for Sustainable Development; Ribeiro, A.B., Mateus, E.P., Couto, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, R.; Schlaak, M.; Siefert, E.; Lord, R.; Connolly, H. Influence of electrical fields (AC and DC) on phytoremediation of metal polluted soils with rapeseed (Brassica napus) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). Chemosphere 2011, 83, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, A.; Hansen, H.K.; Agramonte, M. Electrokinetic remediation with high frequency sinusoidal electric fields. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 79, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, A.; Hansen, H.K.; Cubillos, M. Electrokinetic remediation using pulsed sinusoidal electric field. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 86, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, A.; Hansen, H.K.; del Campo, J. Electrodialytic remediation of copper mine tailings with sinusoidal electric field. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2010, 40, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyar, R.; Doulati Ardejani, F.; Farahbakhsh, M.; Norouzi, P.; Yavarzadeh, M.; Maghsoudy, S. Potential of Vetiver grass for the phytoremediation of a real multi-contaminated soil, assisted by electrokinetic. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; El-Araby, H. Electro-agric, a novel environmental engineering perspective to overcome the global water crisis via marginal water reuse. Nat. Hazards Res. 2021, 1, 202–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Alam, M.Z.; Salleh, H.M.; Tanaka, T.; Amosa, M.K.; Iwata, M.; Jami, M.S. Electrokinetic sedimentation: A review. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2016, 19, 374–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamedelhassan, E.; Shang, J.Q. Analysis of electrokinetic sedimentation of dredged Welland River sediment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2001, 85, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; Osman, M.A.; El-Araby, H.; Khalil, A.K.A.; Kotp, Y.H. Electrokinetics-Based Phosphorus Management in Soils and Sewage Sludge. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottosen, L.M.; Jensen, P.E.; Kirkelund, G.M. Phosphorous recovery from sewage sludge ash suspended in water in a two-compartment electrodialytic cell. Waste Manag. 2016, 51, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, V.; Dias-Ferreira, C.; González-García, I.; Labrincha, J.; Horta, C.; García-González, M.C. A novel approach for nutrients recovery from municipal waste as biofertilizers by combining electrodialytic and gas permeable membrane technologies. Waste Manag. 2021, 125, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y. Large scale soft ground consolidation using electrokinetic geosynthetics. Geotext. Geomembr. 2021, 49, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wu, T.; Yao, K.; Kasu, C.M.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Gong, J. Consolidation of soft clay by cyclic and progressive electroosmosis using electrokinetic geosynthetics. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-H.; Lee, Y.-J.; Lee, H.-G.; Ha, T.-H.; Bae, J.-H. Removal characteristics of salts of greenhouse in field test by in situ electrokinetic process. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 86, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, E.D.; Lindgren, E.R. Electrokinetic Extraction of Chromate from Unsaturated Soils. In Emerging Technologies in Hazardous Waste Management V; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 607, pp. 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, E.; Prommer, H.; Dai, X.; Sun, J.; Breuer, P.; Fourie, A. Electrokinetic in situ leaching of gold from intact ore. Hydrometallurgy 2018, 178, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Weber, M.E. Optimal off-time in interrupted electroosmotic dewatering. Sep. Technol. 1996, 6, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; Eissa, D.; Abd-Elmottaleb, O.; Bahgaat, A.K.; Osman, M.A. Optimizing electrokinetic remediation for pollutant removal and electroosmosis/dewatering using lateral anode configurations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; El-Araby, H. Challenges and opportunities in the restoration of soil contaminated by per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) using advanced electrokinetic: A critical review. Ecol. Front. 2025, 45, 1531–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niarchos, G.; Sörengård, M.; Fagerlund, F.; Ahrens, L. Electrokinetic remediation for removal of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) from contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 133041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; Eissa, D.; Yaseen, R.; Ibrahim, G.A.Z.; Osman, M.A. Scaling up soil electrokinetic removal of inorganic contaminants based on lab chemical and biological optimizations. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 11607–11630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Fu, R.; Li, Q. Removal of inorganic contaminants in soil by electrokinetic remediation technologies: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.; Ro, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, S. Electrokinetically enhanced transport of organic and inorganic phosphorus in a low permeability soil. Geosci. J. 2006, 10, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.-T.; Ro, H.-M.; Lee, S.-M. Effects of Triethyl Phosphate and Nitrate on Electrokinetically Enhanced Biodegradation of Diesel in Low Permeability Soils. Environ. Technol. 2007, 28, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shen, Z.; Lei, Y.; Zheng, S.; Ju, B.; Wang, W. Effects of electrokinetics on bioavailability of soil nutrients. Soil Sci. 2006, 171, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, E.-M.M.; Abou-Shady, A.; Ghoniem, A.E.; Abdelhamied, A.S. Enhancement of the electrokinetic removal of heavy metals, cations, anions, and other elements from soil by integrating PCPSS and a chelating agent. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2022, 134, 104306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadi, S.; Saeedi, M.; Mollahosseini, A. Enhanced electrokinetic remediation of mixed contaminants from a high buffering soil by focusing on mobility risk. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasbian, I.; Safari Sinegani, A.A. Improving the efficiency of phytoremediation using electrically charged plant and chelating agents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 2479–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Wang, L.; Ke, H.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, C.; Jiang, M.; Zhan, F.; Li, T. Effects, physiological response and mechanism of plant under electric field application. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 329, 112992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, G.; Weigand, H.; Marb, C.; Weiß, W.; Huwe, B. Electrokinetic phosphorus recovery from packed beds of sewage sludge ash: Yield and energy demand. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2010, 40, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhu, H.; Wu, X.; Dai, L.; Chen, R.; Jin, Y.; Van der Bruggen, B. Retrieval of trivalent chromium by converting it to its dichromate state from soil using a bipolar membrane electrodialysis system combined with H2O2 oxidation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 300, 121882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y. Flotation-assisted electrodeposition process to recover copper from waste printed circuit boards. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probstein, R.F.; Hicks, R.E. Removal of contaminants from soils by electric fields. Science 1993, 260, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acar, Y.B.; Alshawabkeh, A.N. Principles of electrokinetic remediation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1993, 27, 2638–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, Y.B.; Alshawabkeh, A.N.; Gale, R.J. Fundamentals of extracting species from soils by electrokinetics. Waste Manag. 1993, 13, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, Y.B.; Gale, R.J.; Alshawabkeh, A.N.; Marks, R.E.; Puppala, S.; Bricka, M.; Parker, R. Electrokinetic remediation: Basics and technology status. J. Hazard. Mater. 1995, 40, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonnittan, A.; Sillanpää, M. Application of electrokinetic Fenton process for the remediation of soil contaminated with HCB. In Advanced Water Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kothai, A.; Sathishkumar, C.; Muthupriya, R.; Sankar, K.S.; Dharchana, R. Experimental investigation of textile dyeing wastewater treatment using aluminium in electro coagulation process and Fenton’s reagent in advanced oxidation process. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifon, B.E.; Togbé, A.C.F.; Tometin, L.A.S.; Suanon, F.; Yessoufou, A. Metal-Contaminated Soil Remediation: Phytoremediation, Chemical Leaching and Electrochemical Remediation. In Metals in Soil—Contamination and Remediation; Begum, Z.A., Rahman, I.M.M., Hasegawa, H., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2019; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, L.; Liu, H. Water electrolysis using plate electrodes in an electrode-paralleled non-uniform magnetic field. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 3329–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaithambi, P.; Sajjadi, B.; Abdul Aziz, A.R.; Wan Daud, W.M.A. Bin Performance evaluation of hybrid electrocoagulation process parameters for the treatment of distillery industrial effluent. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2016, 104, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici Guvenc, S.; Dincer, K.; Varank, G. Performance of electrocoagulation and electro-Fenton processes for treatment of nanofiltration concentrate of biologically stabilized landfill leachate. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 31, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Peng, C.; Xu, H.; Ahmed, A.-S. Removal of nitrate from groundwater using the technology of electrodialysis and electrodeionization. Desalination Water Treat. 2011, 34, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deivayanai, V.C.; Karishma, S.; Thamarai, P.; Yaashikaa, P.R.; Saravanan, A. A comprehensive review on electrodeionization techniques for removal of toxic chloride from wastewater: Recent advances and challenges. Desalination 2024, 570, 117098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; Yu, W. Recent advances in electrokinetic methods for soil remediation. A critical review of selected data for the period 2021–2022. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; El-Araby, H.; Osman, M.A. Comprehensive Analysis and Optimization Techniques for Preventing Cracking During Soil Electrokinetic Remediation. Indian Geotech. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mašek, O.; Li, H.; Yu, F.; Wurzer, C.; Wang, J.; Yan, B.; Cui, X.; Chen, G.; Hou, L. Coupling electrokinetic technique with hydrothermal carbonization for phosphorus-enriched hydrochar production and heavy metal separation from sewage sludge. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, H.; Qu, G.; Yang, J.; Jin, C.; Wu, F.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Qin, J.; et al. Aluminium sulfate synergistic electrokinetic separation of soluble components from phosphorus slag and simultaneous stabilization of fluoride. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 328, 116942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; Chen, B.; Qu, G.; Qin, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, F.; He, M. NaHCO3 synergistic electrokinetics extraction of F, P, and Mn from phosphate ore flotation tailings. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 54, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, X.; Fang, C.; Yu, F.; Zhi, J.; Mašek, O.; Yan, B.; Chen, G.; Dan, Z. Agent-assisted electrokinetic treatment of sewage sludge: Heavy metal removal effectiveness and nutrient content characteristics. Water Res. 2022, 224, 119016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traina, G.; Ferro, S.; De Battisti, A. Electrokinetic stabilization as a reclamation tool for waste materials polluted by both salts and heavy metals. Chemosphere 2009, 75, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ling, Z.; Zhao, M.; Sha, L.; Li, C.; Lu, X. Investigation of the properties and mechanism of activated sludge in acid-magnetic powder conditioning and vertical pressurized electro-dewatering (AMPED) process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 328, 124973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; El-Araby, H. Controlling the pH of soil, catholyte, and anolyte for sustainable soil electrokinetics remediation: A descriptive review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 237, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; El-Araby, H. Soil electrokinetic remediation to restore mercury-polluted soils: A critical review. Chemosphere 2025, 377, 144336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; El-Araby, H.; Osman, M.A. An overview of integrated soil electrokinetic/electroosmosis-vacuum systems for sustainable soil improvement and contaminants separation. Indian Geotech. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; El-Araby, H. Reverse Polarity-Based Soil Electrokinetic Remediation: A Comprehensive Review of the Published Data during the Past 31 Years (1993–2023). ChemEngineering 2024, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; El-Araby, H.; El-Harairy, A.; El-Harairy, A. Utilizing the approaching/movement electrodes for optimizing the soil electrokinetic remediation: A comprehensive review. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 50, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A. A critical review of enhanced soil electrokinetics using perforated electrodes, pipes, and nozzles. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2024, 19, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.; El-Araby, H. A comprehensive analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of pulsed electric fields during soil electrokinetic remediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 3895–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-N.; Jung, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-J.; Moon, J.-K.; Jung, C.-H. An analysis of a flushing effect on the electrokinetic-flushing removal of cobalt and cesium from a soil around decommissioning site. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 63, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-N.; Jung, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-J.; Moon, J.-K.; Jung, C.-H. Development of electrokinetic-flushing technology for the remediation of contaminated soil around nuclear facilities. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2008, 14, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Kim, S.S. Application of enhanced electrokinetic extraction for lead spiked kaolin. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2003, 7, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Qian, Z.; Xiong, X.; Dong, C.; Song, Z.; Shi, Y.; Wei, Z.; Jin, M. Cationic polyacrylamide (CPAM) enhanced pressurized vertical electro-osmotic dewatering of activated sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 818, 151787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Wang, Y.-L.; Ji, X.-Y. Dynamic changes in the characteristics and components of activated sludge and filtrate during the pressurized electro-osmotic dewatering process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 134, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.; Pang, H.; Fan, F.; Zhang, J.; Xu, P.; Qiu, S.; Wu, X.; Lu, X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, G.; et al. Pore-scale model and dewatering performance of municipal sludge by ultrahigh pressurized electro-dewatering with constant voltage gradient. Water Res. 2021, 189, 116611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Lai, Z.; Hu, M.; Han, X.; Su, Y. Effects of frequency and duty cycle of pulsating direct current on the electro-dewatering performance of sewage sludge. Chemosphere 2020, 243, 125372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendinning, S.; Hall, J.A.; Lamont-Black, J.; Jones, C.J.F.P.; Huntley, D.T.; White, C.; Fourie, A. Dewatering Sludge Using Electrokinetic Geosynthetics BT. In Advances in Environmental Geotechnics, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Geoenvironmental Engineering in Hangzhou, China, 8–10 September 2009; Chen, Y., Zhan, L., Tang, X., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Fourie, A.B.; Jones, C.J.F.P. Improved estimates of power consumption during dewatering of mine tailings using electrokinetic geosynthetics (EKGs). Geotext. Geomembr. 2010, 28, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendinning, S.; Lamont-Black, J.; Jones, C.J.F.P. Treatment of sewage sludge using electrokinetic geosynthetics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 139, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.Y.; Taibi, S.; Souli, H.; Fleureau, J.-M. The Effect of pH on Electro-osmotic Flow in Argillaceous Rocks. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2013, 31, 1335–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.R.; Nekrasevits, A.; Semken, R.S.; Mikkola, A.; Sihvonen, T. Applying ultrasound plus electrokinetics to enhance sludge dewatering. Dry. Technol. 2022, 40, 2990–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, P.-A.; Jurate, V.; Mika, S. Electro-Dewatering of Sludge under Pressure and Non-Pressure Conditions. Environ. Technol. 2008, 29, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citeau, M.; Olivier, J.; Mahmoud, A.; Vaxelaire, J.; Larue, O.; Vorobiev, E. Pressurised electro-osmotic dewatering of activated and anaerobically digested sludges: Electrical variables analysis. Water Res. 2012, 46, 4405–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Fan, X.; Han, Z.; Yu, F. Siderite/PMS conditioning-pressurized vertical electro-osmotic dewatering process for activated sludge volume reduction: Evolution of protein secondary structure and typical amino acid in EPS. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Qian, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, H. Magnetic micro-particle conditioning–pressurized vertical electro-osmotic dewatering (MPEOD) of activated sludge: Role and behavior of moisture and organics. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 74, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gingerich, I.; Neufeld, R.D.; Thomas, T.A. Electroosmotically enhanced sludge pressure filtration. Water Environ. Res. 1999, 71, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani Baker, M.; Elektorowicz, M.; Hanna, A. Electrokinetic nondestructive in-situ technique for rehabilitation of liners damaged by fuels. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 359, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-S.; Ou, C.-Y.; Chien, S.-C. Cohesive Strength Improvement Mechanism of Kaolinite Near the Anode During Electroosmotic Chemical Treatment. Clays Clay Miner. 2018, 66, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Han, S.-J. Application of the electrokinetic-Fenton process for the remediation of kaolinite contaminated with phenanthrene. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 118, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Han, S.-J.; Kim, S.-S.; Yang, J.-W. Effect of soil chemical properties on the remediation of phenanthrene-contaminated soil by electrokinetic-Fenton process. Chemosphere 2006, 63, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.H. Switching effects of electrode polarity and introduction direction of reagents in electrokinetic-Fenton process with anionic surfactant for remediating iron-rich soil contaminated with phenanthrene. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 8094–8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Fan, X.; Qian, Y. In situ bioelectrokinetic remediation of phenol-contaminated soil by use of an electrode matrix and a rotational operation mode. Chemosphere 2006, 64, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.W.; Wang, F.Y.; Huang, Z.H.; Wang, H. Simultaneous removal of 2,4-dichlorophenol and Cd from soils by electrokinetic remediation combined with activated bamboo charcoal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 176, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.; Chiang, T.-S. The mechanisms of arsenic removal from soil by electrokinetic process coupled with iron permeable reaction barrier. Chemosphere 2007, 67, 1533–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lear, G.; Harbottle, M.J.; Sills, G.; Knowles, C.J.; Semple, K.T.; Thompson, I.P. Impact of electrokinetic remediation on microbial communities within PCP contaminated soil. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 146, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacicco, A.; De Gioannis, G.; Muntoni, A.; Pettinao, E.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R. Enhanced electrokinetic treatment of marine sediments contaminated by heavy metals and PAHs. Chemosphere 2010, 81, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, I.; Mohamedelhassan, E.; Yanful, E.K. Solar powered electrokinetic remediation of Cu polluted soil using a novel anode configuration. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 181, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannelli, R.; Masi, M.; Ceccarini, A.; Ostuni, M.B.; Lageman, R.; Muntoni, A.; Spiga, D.; Polettini, A.; Marini, A.; Pomi, R. Electrokinetic remediation of metal-polluted marine sediments: Experimental investigation for plant design. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 181, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Guo, S.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Effect of polarity-reversal on electrokinetic enhanced bioremediation of Pyrene contaminated soil. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 187, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroun, M.; Chilingar, G.V.; Pamukcu, S. The efficacy of using electrokinetic transport in highly-contaminated offshore sediments. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2010, 40, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; Iannelli, R.; Losito, G. Ligand-enhanced electrokinetic remediation of metal-contaminated marine sediments with high acid buffering capacity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 10566–10576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estabragh, A.R.; Bordbar, A.T.; Ghaziani, F.; Javadi, A.A. Removal of MTBE from a clay soil using electrokinetic technique. Environ. Technol. 2016, 37, 1745–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, T.R.; Tarman, B. Preliminary Results from the Investigation of Thermal Effects in Electrokinetic Soil Remediation. In Emerging Technologies in Hazardous Waste Management V; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 607, pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Ye, H.; Alshawabkeh, A.N. Soil improvement by electroosmotic grouting of saline solutions with vacuum drainage at the cathode. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 114, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ding, M.; Shen, K.; Cui, J.; Chen, W. Removal of aluminum from drinking water treatment sludge using vacuum electrokinetic technology. Chemosphere 2017, 173, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, R.; Cai, Y.; Fu, H.; Li, X.; Hu, X. Vacuum preloading and electro-osmosis consolidation of dredged slurry pre-treated with flocculants. Eng. Geol. 2018, 246, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Weber, M.E.; Pirkonen, P.M. Electrokinetically enhanced vacuum dewatering of mineral slurries. Filtr. Sep. 1996, 33, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, R. Experimental study on the improvement of sludge by vacuum preloading-stepped electroosmosis method with prefabricated horizontal drain. Geotext. Geomembr. 2024, 52, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukleja, J. Stabilization of Landslides Sliding Layer Using Electrokinetic Phenomena and Vacuum Treatment. Geosciences 2020, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Yan, C.; Yang, X.; Jin, Z.; Li, L.; Huang, C.; Yu, L.; Huang, L. Study of quickly separating water from tunneling slurry waste by combining vacuum with electro-osmosis. Environ. Technol. 2021, 42, 2540–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Gao, M.; Yu, X. Vacuum Preloading Combined with Electro-Osmotic Dewatering of Dredger Fill Using Electric Vertical Drains. Dry. Technol. 2015, 33, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Geng, J.; Wei, G.; Li, W. Engineering application of vacuum preloading combined with electroosmosis technique in excavation of soft soil on complex terrain. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y. Field Test on Consolidation of Hydraulically Filled Sludge via Vertical Gradient Electro-osmotic Dewatering. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2022, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shen, Y.; Qi, W.; Chen, K. Experimental study on electrode materials characteristics for dewatering and remediation of copper-contaminated sediment from Tai Lake based on vacuum electro-osmosis. J. Cent. South Univ. 2024, 31, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Shen, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, K. Study on the Interaction between the Reduction and Remediation of Dredged Sediments from Tai Lake Based on Vacuum Electro-Osmosis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, L. Laboratory tests of electro-osmotic consolidation combined with vacuum preloading on kaolinite using electrokinetic geosynthetics. Geotext. Geomembr. 2019, 47, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-H.; Yang, J.-W. A new method to control electrolytes pH by circulation system in electrokinetic soil remediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2000, 77, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-H.; Liao, Y.-C. The effect of critical operational parameters on the circulation-enhanced electrokinetics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 129, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Yuan, S.; Chen, J.; Li, T.; Lin, L.; Lu, X. Solubility-enhanced electrokinetic movement of hexachlorobenzene in sediments: A comparison of cosolvent and cyclodextrin. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 166, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Z.; Lu, J.; Zang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zou, X.; Cui, J. Efficient removal of Cr(VI) from contaminated kaolin and anolyte by electrokinetic remediation with foamed iron anode electrode and acetic acid electrolyte. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Lv, H.; Cui, C. Unique role of sulfonic acid exchange resin on preventing copper and zinc precipitation and enhancing metal removal in electrokinetic remediation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falamaki, A.; Noorzad, A.; Homaee, M.; Vakili, A.H. Soil Improvement by Electrokinetic Sodium Silicate Injection into a Sand Formation Containing Fine Grains. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2024, 42, 4913–4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Guo, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S. Comparison of approaching and fixed anodes for avoiding the ‘focusing’ effect during electrokinetic remediation of chromium-contaminated soil. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 203, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Guo, S.; Wu, B.; Li, F.; Li, G. Effects of reducing agent and approaching anodes on chromium removal in electrokinetic soil remediation. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2016, 10, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, T.; Li, G.; Li, F.; Guo, S. Enhanced electrokinetic remediation of chromium-contaminated soil using approaching anodes. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2012, 6, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, I.A.; Mohamedelhassan, E.E.; Yanful, E.K.; Weselowski, B.; Yuan, Z.-C. Isolation and characterization of novel bacterial strains for integrated solar-bioelectrokinetic of soil contaminated with heavy petroleum hydrocarbons. Chemosphere 2019, 237, 124514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, I.; Mohamedelhassan, E.; Yanful, E.; Bo, M.W. Enhanced electrokinetic bioremediation by pH stabilisation. Environ. Geotech. 2018, 5, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.L.; Saéz, C.; Llanos, J.; Lanza, M.R.V.; Cañizares, P.; Rodrigo, M.A. Solar-powered electrokinetic remediation for the treatment of soil polluted with the herbicide 2,4-D. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 190, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Bai, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Yao, M.; Zhao, Y. Lab scale-study on the efficiency and distribution of energy consumption in chromium contaminated aquifer electrokinetic remediation. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 25, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D.C.; Đolić, M.B.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; dos Santos, E.V.; Silva, T.F.C.V.; Vilar, V.J.P. Coupling electrokinetic with a cork-based permeable reactive barrier to prevent groundwater pollution: A case study on hexavalent chromium-contaminated soil. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 429, 140936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Gong, W.; Chen, Y.; Hong, J.; Wang, Y. Influence of polarity exchange frequency on electrokinetic remediation of Cr-contaminated soil using DC and solar energy. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 153, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, F.; Li, P.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, G.; Wu, B.; Tai, P. Study on Remediation Technologies of Organic and Heavy Metal Contaminated Soils BT. In Twenty Years of Research and Development on Soil Pollution and Remediation in China; Luo, Y., Tu, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tian, Y.; Liu, W.; Long, Y.; Ye, J.; Li, B.; Li, N.; Yan, M.; Zhu, C. Impact of electrokinetic remediation of heavy metal contamination on antibiotic resistance in soil. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 400, 125866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, S.; Villaseñor, J.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Cañizares, P. Can electro-bioremediation of polluted soils perform as a self-sustainable process? J. Appl. Electrochem. 2018, 48, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhuang, Y. Removal of Chromium from Contaminated Soil by Electrokinetic Remediation Combined with Adsorption by Anion Exchange Resin and Polarity Reversal. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2024, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-G.; Hong, K.-K.; Kim, Y.-W.; Lee, J.-Y. Enhanced electrokinetic (E/K) remediation on copper contaminated soil by CFW (carbonized foods waste). J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; van Doren, J.; Fang, Z.; Li, W. Improvement in electrokinetic remediation of Pb-contaminated soil near lead acid battery factory. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 3088–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, M.H.; Mu’azu, N.D.; Lukman, S.; Bukhari, A. Application of box-behnken design to hybrid electrokinetic-adsorption removal of mercury from contaminated saline-sodic clay soil. Soil Sediment Contam. An Int. J. 2015, 24, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q. Insights into the remediation of cadmium-pyrene co-contaminated soil by electrokinetic and the influence factors. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Díaz, H.L.; López-Bellido, F.J.; Alonso-Azcárate, J.; Fernández-Morales, F.J.; Rodríguez, L. Comprehensive study of electrokinetic-assisted phytoextraction of metals from mine tailings by applying direct and alternate current. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 445, 142051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohrazi, A.; Ghasemi-Fasaei, R.; Mojiri, A.; Shirazi, S.S. Investigating an electro-bio-chemical phytoremediation of multi-metal polluted soil by maize and sunflower using RSM-based optimization methodology. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 211, 105352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Dai, H.; Skuza, L.; Wei, S. The effects of different electric fields and electrodes on Solanum nigrum L. Cd hyperaccumulation in soil. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohner, S.T.; Becker, D.; Mangold, K.-M.; Tiehm, A. Sequential Reductive and Oxidative Biodegradation of Chloroethenes Stimulated in a Coupled Bioelectro-Process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 6491–6497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.N.O.; Paiva, S.S.M.; Souza, F.L.; Silva, D.R.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Santos, E.V. Applicability of electrochemical technologies for removing and monitoring Pb2+ from soil and water. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018, 816, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Cheng, F.; Guo, P.; Guo, S. Enhancement of electrokinetic-bioremediation by ryegrass: Sustainability of electrokinetic effect and improvement of n-hexadecane degradation. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.I. Dewatering and decontamination of artificially contaminated sediments during electrokinetic sedimentation and remediation processes. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2006, 10, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijoo, J.; Ottosen, L.M.; Nóvoa, X.R.; Rivas, T.; de Rosario, I. An improved electrokinetic method to consolidate porous materials. Mater. Struct. 2017, 50, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Chen, X.; Jia, J.; Qu, L.; Wang, W. Comparison of electrokinetic soil remediation methods using one fixed anode and approaching anodes. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 150, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.J.; Shen, Z.M.; Yuan, T.; Zheng, S.S.; Ju, B.X.; Wang, W.H. Enhancing electrokinetic remediation of cadmium- contaminated soils with stepwise moving anode method. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A Toxic/Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 2006, 41, 2517–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Qu, L.; Dong, Z.; Zheng, S.; Wang, W. A modified EK method with an I−/I2 lixiviant assisted and approaching cathodes to remedy mercury contaminated field soils. Environ. Geol. 2009, 57, 1399–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Cai, Z.; Sun, S.; Romantschuk, M.; Sinkkonen, A.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q. Electrokinetic-enhanced remediation of actual arsenic-contaminated soils with approaching cathode and Fe0 permeable reactive barrier. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.-S.; Sen Gupta, B.; Hashim, M.A. Remediation of Pb/Cr co-contaminated soil using electrokinetic process and approaching electrode technique. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K.B.; Jensen, P.E.; Ottosen, L.M.; Barlindhaug, J. Influence of electrode placement for mobilising and removing metals during electrodialytic remediation of metals from shooting range soil. Chemosphere 2018, 210, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Fischer, R.; Sillanpää, M. Investigations on different positions of electrodes and their effects on the distribution of Cr at the water sediment interface. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 4, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoghi, H.; Ghazavi, M.; Ganjian, N. Pilot-scale electrokinetic treatment of dispersive soil and feasibility study of sodium ion transport across the soil by electric field relocation. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeira, J.; Peng, C.; Abou-Shady, A. Enhancement of ion transport in porous media by the use of a continuously reoriented electric field. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2012, 13, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Almeira, J.O.; Abou-Shady, A. Enhancement of ion migration in porous media by the use of varying electric fields. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 118, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | The Type of Polluted Soil | Initial Concentrations of Contaminants | SKE Equipment Type | Composition of the Electrode | The Pressure Condition | The Voltage or Current Applied | Experimental Period | The Primary Findings from This Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Real soil with pH (5.9–6.9) [63]. | The concentrations of Co2+ and Cs+ were 238 mg/kg and 514 mg/kg. | Horizontal design. | Titanium. | The anode chamber had a pump attached. | 20–50 mA. | 10–15 days. |

|

| 2 | Real soil with pH (5.9–6.9) [64]. | Artificially contaminated with 0.01 M of Co2+ and Cs+. | Horizontal design. | Titanium. | The anode chamber had a pump attached. | 2 V/cm. | 15 days. | When compared to an electrokinetic remediation traditional design, the removal efficiencies of Cs+ and Co2+ were enhanced by 7.7% and 6.8%, respectively, by an electrokinetic-flushing remediation with pump pressure for 15 days. |

| 3 | Kaolinite [65]. | Artificially contaminated with Pb (300 and 1780 mg/kg). | Mixed design (horizontal and vertical) | Carbon. | A hydraulic head difference was used to pump sodium dodecyl sulfate and citric acid into the cathode reservoir on days seven and eight via the cathode effluent tube. The applied injection pressure was 29.42 kPa. | 12 V/cm. | 12 days. | Simultaneous injection of citric acid and sodium dodecyl sulfate solution with electrode polarity reversal decreased Pb precipitation and raised the removal rate in the cathode area by three times when compared to the unimproved approach. |

| No. | The Type of Polluted Soil | SKE Equipment Type | Composition of the Electrode | The Pressure Condition | The Voltage or Current Applied | Experimental Period | The Primary Findings from This Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sludge with pH 7.02 [66]. | Vertical design. | A titanium dish anode and a stainless-steel cathode. | Sludge (100 g) was processed with a pressure of 2 MPa. | 19.3 V. | 15 min. | The sludge developed a homogeneous and porous structure with the addition of the ideal CPAM dosage, which offered water channels and improved electric transport, hence encouraging the breakdown of extracellular polymeric materials. |

| 2 | Activated sludge with pH 7.12 and EC 1.39 mS/cm [67]. | Vertical design. | Titanium-coated mixed metal oxide. | The piston was subjected to a steady pressure of 200, 400, or 600 kPa during the compression stage. | 10, 30, and 50 V. | 2 h. | Although a single pressure of 600 kPa was able to remove just a little amount of free and bound water from the activated sludge, the application of 50 V voltage during electrical compression caused both types of water to further decrease to 0.24 g−1 dry solid and 0.25 g−1 dry solid. |

| 3 | Municipal sludge [68]. | Vertical design. | Titanium alloy and graphite are used to make the anode and cathode plates. | Three dewatering modes were used in this study: “ultrahigh-pressure mechanical dewatering mode (UMDW), pressurized electro-dewatering (PEDW) with constant voltage mode (U-PEDW) and constant voltage gradient mode (G-PEDW)”. The applied pressure ranges were 2, 4, 6, and 8 MPa. | 20, 30, 36, 40, 50, and 60 V. | 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 min. | When compared to UMDW and U-PEDW modes, the G-PEDW mode, with the lowest moisture content and lowest energy usage, shows superior dewatering performance. |

| 4 | Sewage sludge with pH 7.31 and EC 1.54 mS/cm [69]. | Vertical design. | - | The cylinder was filled with 110 g of the sludge sample, which the anodic plate squeezed for 30 min at 0.6 MPa of pressure. | 10, 20, 36, 40, and 50 V. | 30 min. | An electro-dewatering technique that shows promise for the future is pulsating direct current-dewatering, which was shown to be more energy efficient than stable direct current-dewatering. |

| No. | The Type of Polluted Soil | SKE Equipment Type | Composition of the Electrode | The Pressure Condition | The Voltage or Current Applied | Experimental Period | The Primary Findings from This Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sand-bentonite [80]. | Vertical design. | Perforated stainless steel mesh electrodes. | The tests were performed on liners infiltrated firstly with water, and then with alternative fuels such as biofuel and ethanol. The test was conducted using water under a pressure of 40 kPa to completely percolate the liner. | 0.5 V/cm. | Refer to [80]. | Under pressure of 40 kPa, electro-rehabilitation for alternative fuels resulted in a four-fold reduction in hydraulic conductivity, and at 100 kPa, it was a three-fold reduction. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abou-Shady, A.; El-Araby, H. A Mini Review of Pressure-Assisted Soil Electrokinetics Remediation for Contaminant Removal, Dewatering, and Soil Improvement. Pollutants 2025, 5, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants5040046

Abou-Shady A, El-Araby H. A Mini Review of Pressure-Assisted Soil Electrokinetics Remediation for Contaminant Removal, Dewatering, and Soil Improvement. Pollutants. 2025; 5(4):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants5040046

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbou-Shady, Ahmed, and Heba El-Araby. 2025. "A Mini Review of Pressure-Assisted Soil Electrokinetics Remediation for Contaminant Removal, Dewatering, and Soil Improvement" Pollutants 5, no. 4: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants5040046

APA StyleAbou-Shady, A., & El-Araby, H. (2025). A Mini Review of Pressure-Assisted Soil Electrokinetics Remediation for Contaminant Removal, Dewatering, and Soil Improvement. Pollutants, 5(4), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants5040046