1. Introduction

Data protection regulation serves as a reference for dealing with personal information, and it applies to public and private companies. It outlines the principles of data protection, including privacy rights, security measures, and penalties for non-compliance. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a comprehensive data protection law by the European Union (EU) [

1]. The GDPR’s influence extends beyond the EU due to the global nature of the internet and business operations.

A few years later, Brazil launched its general data protection law (LGPD—Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados) [

2]. The LGPD was created under principles and objectives similar to the European GDPR [

3]. The European Union even states that a company anywhere in the world that has customers in Brazil and already complies with the GDPR is also already complying with the LGPD [

1].

Several risks can be pointed out regarding the indiscriminate use of personal data. Automated profiling and data mining with personal data can generate de-individualization, information asymmetries, and discrimination [

4,

5]. The situation appears worse when considering the fact that the use of personal data can violate laws and even be used for cross-border crimes such as espionage and other crimes, which are called “data war” [

6]. Therefore, in addition to the regulations of each country or region, there is an urgent need to create robust international legal frameworks [

6,

7].

On the other hand, just as there are harmful applications of data access tools, it is possible to use data mining and artificial intelligence tools to fight crime. Some practices called Fraud Analytics promise to be more efficient in the fight against fraud [

7]. The main topics studied within this field of research are insurance, payments, and accounting fraud. It is a field of study with a great tendency to grow, as it must always keep pace with the development of data analysis technologies both for detecting and reducing fraud and preventing it [

8].

Even so, GDPR has had little influence on consumers five years after its launch [

9]. This means that even though the level of knowledge about security and technology has increased over the years, there are still questions about the regulation’s viability, and most survey participants do not take preventative measures to protect their privacy.

Proper implementation of the LGPD presents some challenges for public managers when drawing up policies requiring the processing of personal data, including training agents to comply with the law, transparency, minimizing the data collected, governance, and the possibility of deleting the data collected [

9]. These shortcomings most likely apply to all organizations that collect personal information.

Furthermore, the privacy policies of apps in Brazil are characterized by being excessively long and poorly readable [

10]. In addition, many of them lack the information that discredited these policies’ compliance with the LGPD. Results like this show the urgent need for inspections and the creation of policies to protect personal data. In fact, less than 30% of companies follow the principles of the LGPD [

11]. The percentage is even lower when it comes to governance over-compliance with the law and the process of communicating with the customer when a data breach occurs.

Analyzing legal documents can give directions on actions to be taken within data prevention or at least can help in understanding the main problems of this nature occurring in society. When analyzing the fines imposed and listing which articles of the law were cited in these decisions, fundamental articles of the GDPR were the most cited in the following order: those on principles, lawfulness, and information security. The latter shows that the most common decisions are related to data breaches or security failures [

12].

As the Brazilian LGPD makes those who process the data responsible for it and creates a legal basis for defending people, including penalties in the event of noncompliance or injuries, the legal system is a way for the user to seek redress. This provides a rich source of information issued by Brazilian courts regarding their decisions and other documents.

Thus, knowing all the problems and challenges mentioned above, it is worth analyzing the conduct of these legal proceedings in Brazil because this understanding can be a driver for drawing up more effective policies to protect users. This study is based on the scraping of open data from legal cases, considering a search string with terms related to data protection, and analyzing the data by considering the frequency of terms and their typologies in each Brazilian court.

2. Methods

JusBrasil is a Brazilian online platform with an extensive database containing information on various areas of the national legal system. Processes, doctrines, official gazettes, legislation, articles, and news, among others, are examples of resources whose information can be found on the platform. In this study, the focus was on searching for data related to jurisprudence, which consists of sets of information representing the decisions and interpretations of courts regarding specific cases. JusBrasil categorizes such information into six types of jurisprudences:

Súmulas (Legal summaries): a summary or reduced statement that defines the understanding of a process;

Acórdãos (Judgments): the collective legal position of a group or body regarding the definition of a case or proceeding;

Decisões (Decisions): an expression about the closure of a judicial process;

Sentenças (Sentences): the formal and solemn act that ends the judicial process, pronounced by the judge after analyzing the evidence and arguments of the parties; A judicial decision is only a sentence when both elements (content and function) are present;

Despachos (Orders or Dispatches): legal authorization to proceed with a process;

Orientações jurisprudenciais (Jurisprudential guidelines): used only in the Labor Court, this has the same objective as the summary but differs in that it has greater dynamism.

Considering this, an analysis was carried out on search terms for legal processes to determine which terms were most relevant to this research, and those that stood out were those related to Brazil’s General Data Protection Law (LGPD) and the components directly related to data security and information processing. The data scraping process follows a pipeline consisting of the following [

13]:

- (i)

Understanding the website structure to achieve the target fields;

- (ii)

Defining the search terms;

- (iii)

Developing an automated agent (scraper) to retrieve the data in the target fields;

- (iv)

Storing the data collected in the appropriate format;

- (v)

Applying data cleaning and normalization;

- (vi)

Applying data analysis to extract descriptive statistics about Brazilian jurisprudence;

- (vii)

Providing proper data visualization and interpretation.

The terms applied in searching the documents were defined based on a constructive process that involved (a) analyzing Brazilian law and the documents produced by the national data agency, as well as scientific articles and dialogue with experts; (b) brainstorming among authors to generate terms; and (c) refining the terms. In addition, acronyms were also considered, resulting in the following set (these terms were searched in Portuguese):

“Database”, “Data protection”, “DPO”, “Personal data”, “Consent”, “Data controller”, “Anonymized data”, “Anonymization”, “Data leakage”, “Sensitive personal data”, “Data processing”, “Data breach”, “Processing agents”, “Publicization”, “ANPD”, “National Data Protection Agency”, “Information security”, “Data regulation”, “Privacy”, “Law Nº 13.709, August 14th, 2018”, “LGPD”, and “General Data Protection Law.”

Data scraping on JusBrasil, however, presented significant challenges due to the platform’s strict security policies:

Automatic blocking of repetitive requests;

Protections against automated scraping: these included Cloudflare blocking and access limitations;

Limitation on retrieved data: JusBrasil restricts the search for jurisprudence based on the number of keywords. If the number of results for a search is too broad, the platform limits the results to 50 pages listing the jurisprudence found, ordered by relevance (determined by the platform itself).

Therefore, so that the limitations of the platform would not compromise the search results, the team developed the strategies of (a) reducing the frequency and intensity of the requests within the JusBrasil platform; (b) using bypass tools; and (c) splitting the search term by term and applying the filter on the type of case law already in the request phase, creating a Cartesian product of these results and allowing for detail and specificity in the analysis.

This last strategy expanded the total capacity for obtaining jurisprudence records up to 34,000 documents in total. However, the direct consequences of its application were an increase in the time taken to collect data and in the work involved in cleaning data, as it was necessary to add a step to eliminate duplicate results.

This resulted in a total of 10,009 documents which, although there is no guarantee that this represents the entire universe of documents related to data protection in the country, (an inherent characteristic of this type of methodology), is the broadest possible result considering the mentioned limitations. In addition to the type of jurisprudence, these documents were classified by their titles, state of issuance, promulgating court, related keywords, and date concerning the LGPD. The cross-analysis of these data made it possible to understand the evolution of court cases on the subject over time and how each Brazilian court and state behaves when analyzing and judging data protection cases.

The data were then analyzed to identify the terms’ frequencies of occurrence and relevance, using graphical representations that facilitated interpreting the results and highlighted significant trends. All steps were performed in an appropriate computational environment, using tools recognized for their efficiency in exploratory analysis and data visualization. This work was conducted with technical rigor, ensuring clarity and objectivity in the presentation of the results.

3. Results and Discussion

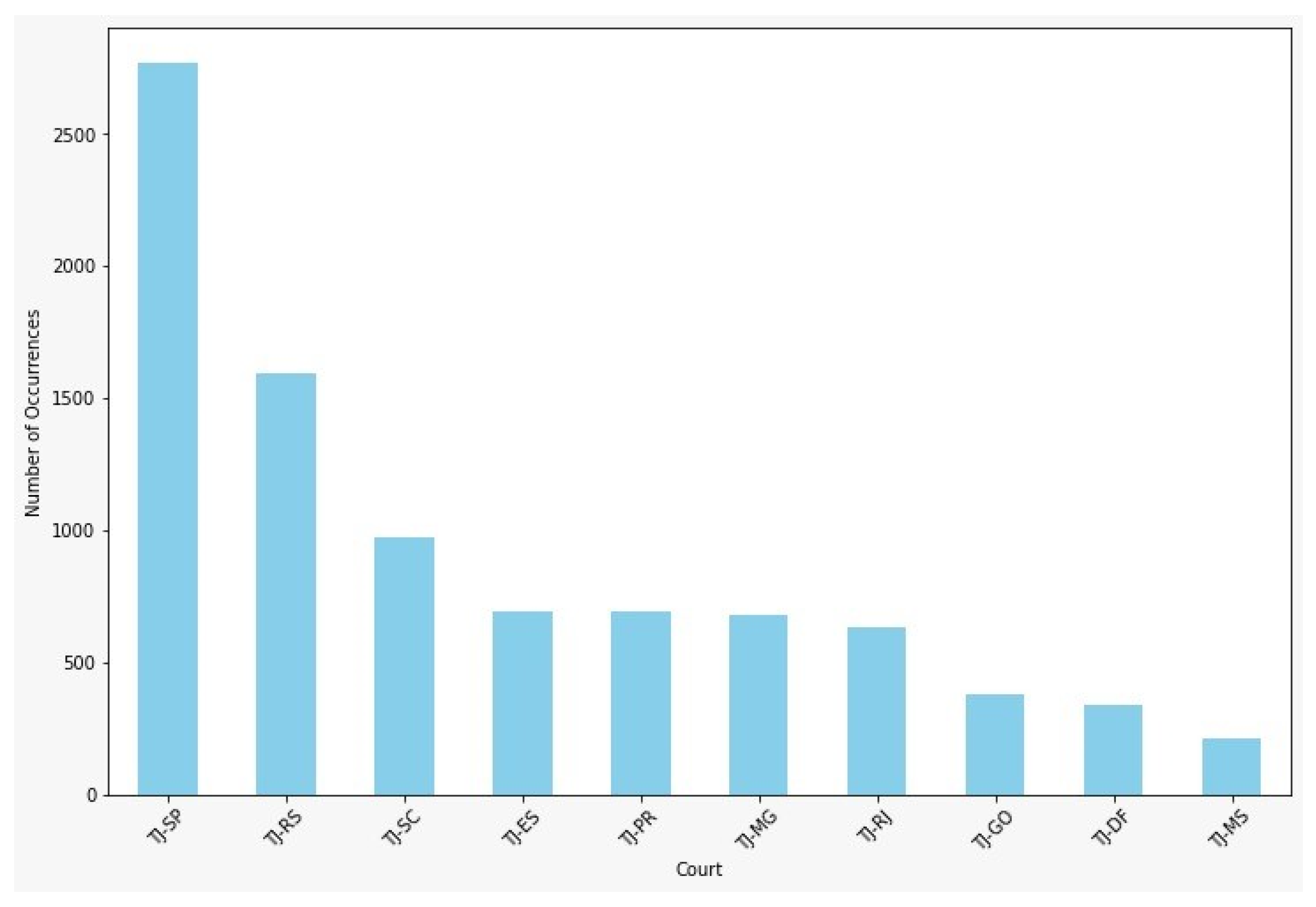

Following the methodological process, it was possible to extract a total of 10,009 documents, and based on them, to obtain some descriptive statistics throughout the process. The graph in

Figure 1 shows the 10 Brazilian Courts of Justice with the highest results according to the terms used.

It should be noted in the graph that the Court of Justice of the State of São Paulo (TJ-SP) leads in the number of results, followed by the Court of Justice of the State of

Rio Grande do Sul (TJ-RS); however, the marked difference in quantity between the states stands out: TJ-SP has 1172 more results than TJ-RS according to the search conducted. The states of the southeast region of Brazil, which include São Paulo (TJ-SP), Rio de Janeiro (TJ-RJ), Minas Gerais (TJ-MG), and Espírito Santo (TJ-ES), are all listed in

Figure 1 among the 10 states with the most results. The three states that make up the Southern region, which includes Rio Grande do Sul (TJ-RS), Paraná (TJ-PR), and Santa Catarina (TJ-SC), are also represented. This shows that the south–southeast axis of Brazil has a high concentration of jurisprudence on the issue of data protection. Finally, there are three representatives from the midwest region of Brazil: the Federal District (TJ-DF) and the states of Goiás (TJ-GO) and Mato Grosso do Sul (TJ-MS).

The southeast of Brazil is the most populous region in the country, is the most economically active and developed, and has the highest concentration of wealth. It was expected that the state of São Paulo, for example, would have the highest search results. The southern region follows the Southeast, with Rio Grande do Sul (TJ-RS) having the second-highest results among all national contexts. Regarding economic development, the southern region is the second most developed in Brazil, with the state of Rio Grande do Sul being the most developed in the region. After the southern region, the Midwest is the third most developed region in the country.

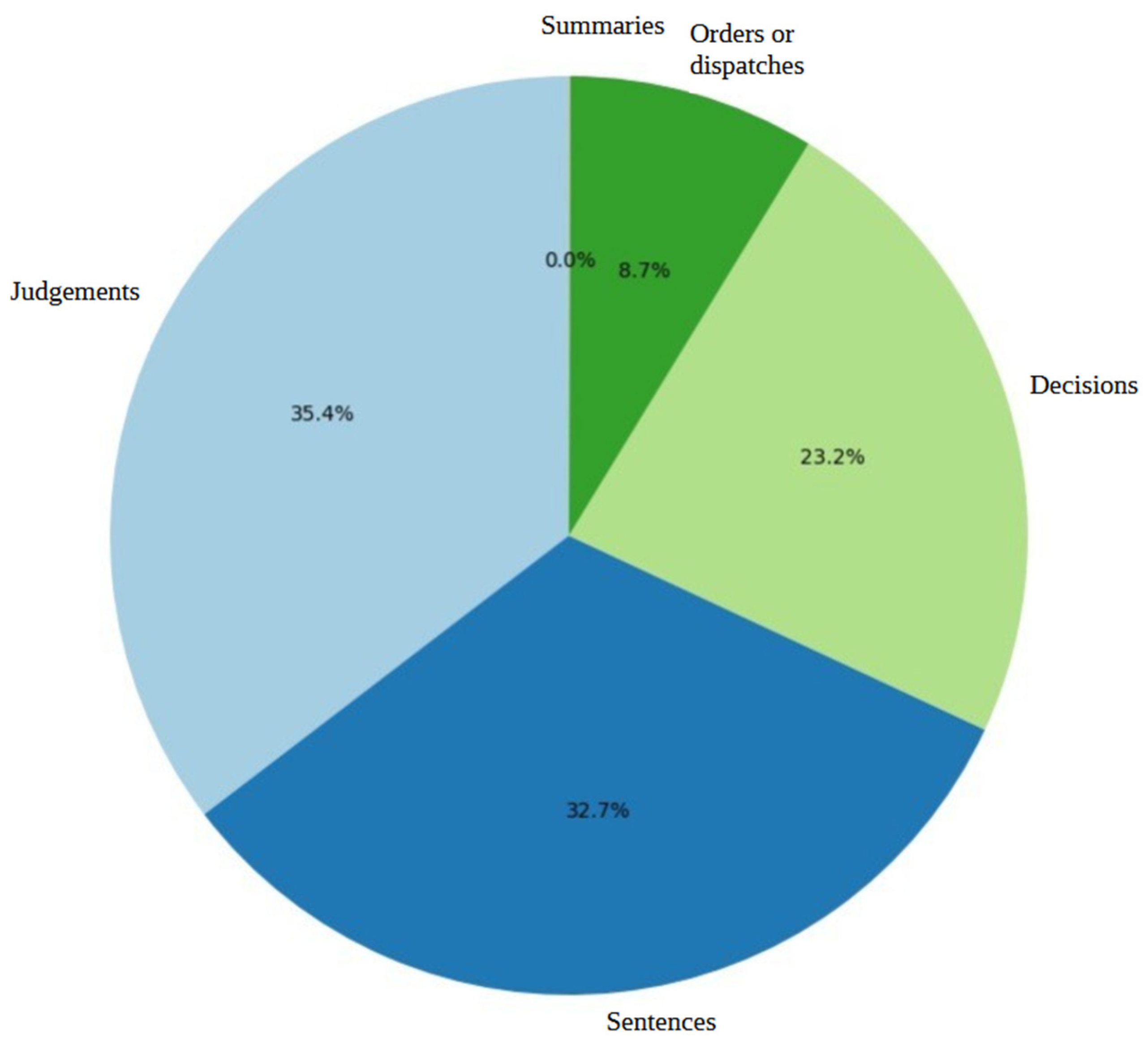

Regarding the distribution of jurisprudences,

Figure 2 contains a graph showing the percentages according to each type as described in the Methods section and found in this study’s searches.

Most of the documents found regarding data protection in Brazil are contained in two types: judgments and sentences, accounting for 68.1% of the total. Notably, no legal summaries (súmulas) were found in the search conducted with the terms used. A practical inference based on this data is that legally, decisions on data protection are more concentrated in the appellate courts. First-degree judges do not apply the rules decisively; only higher instances do, delaying the processes. Courts with multiple judges, such as state and higher courts, are more pragmatic and up-to-date regarding data protection as a constitutional fundamental right.

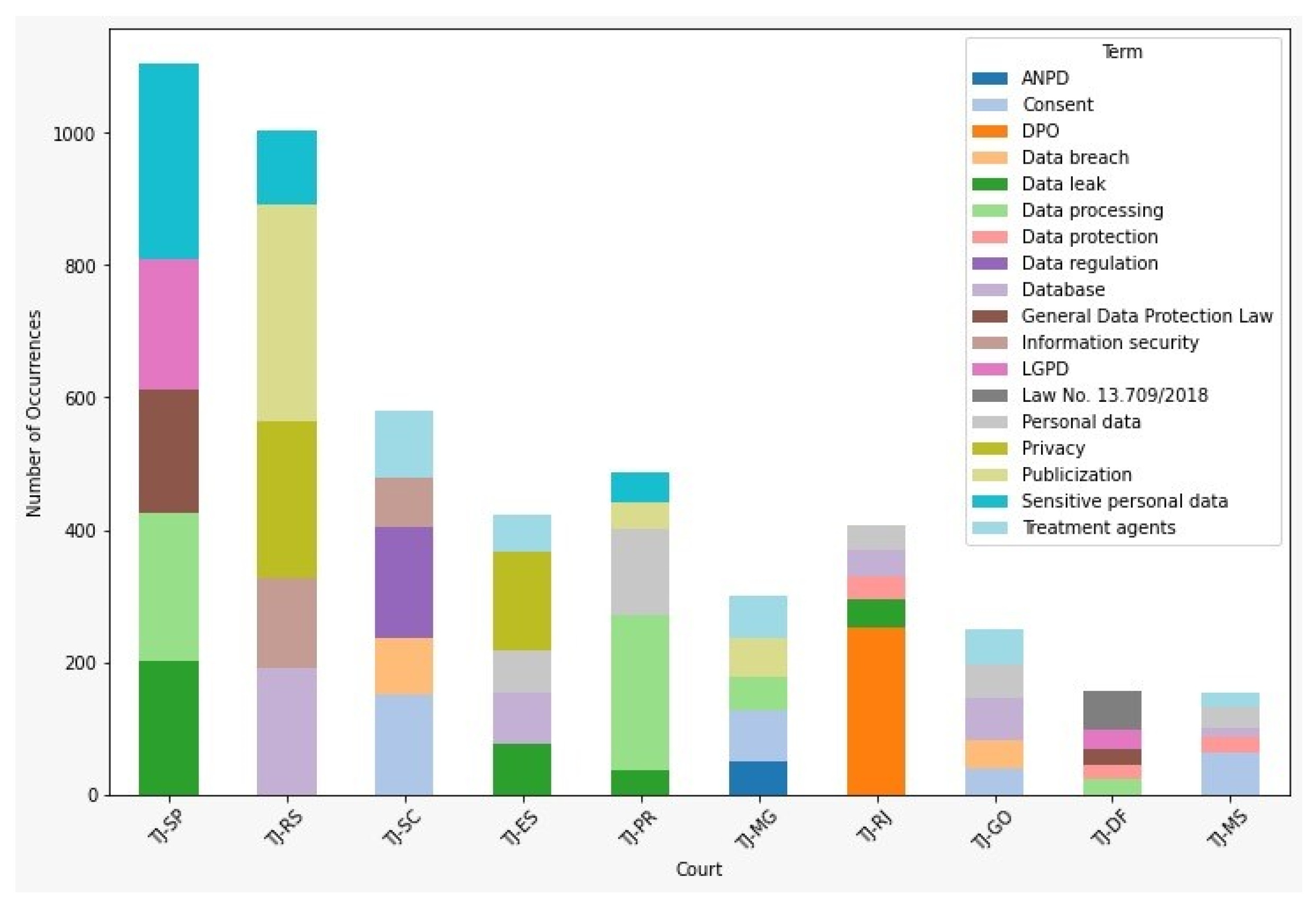

Combining the information from the previous charts, we can understand how much each state produced regarding types of jurisprudence on data protection.

Figure 3 below presents the compositions for the 10 states with the highest results.

For TJ-SP, the most prevalent documents found in the search results are acórdãos (judgments, in blue) and sentenças (sentences, in gray), with decisões (decisions, in green) being significantly fewer in number compared with these two types. TJ-ES, TJ-MG, and TJ-GO also notably have larger quantities of judgments and sentences, with TJ-ES having the most results for sentences after TJ-SP. On the other hand, TJ-RS, TJ-PR, and TJ-MS have higher quantities of decisions than the other courts.

Unlike the rest, the results for TJ-SC (Santa Catarina), TJ-GO (Goiás), and TJ-DF (Distrito Federal) include despachos (orders or dispatches, in brown) that were not found in the searches for the other courts on the topic of data protection.

Another interesting set of statistics refers to the composition of the results associated with the terms used regarding data protection in Brazil.

Figure 4 consists of a graph that separates these compositions according to the results of each of the 10 courts, with the most results matching those previously analyzed in terms of the five most frequent terms found in each court.

It can be observed that the compositions are related to term occurrences within the results and not the document quantities themselves. Taking TJ-SP as an example, the filtering indicates the most recurring terms within its documents as follows: “sensitive personal data”, “LGPD”, “General Data Protection Law”, “data processing”, and “data leak.” The terms LGPD and General Data Protection Law refer to the same object, as the documents sometimes mention the acronym LGPD (the abbreviation for Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados in Portuguese) or the full term.

Although each court may have terms in common with others, as seen with TJ-SC, TJ-ES, TJ-MG, TJ-GO, and TJ-MS which all have the term “treatment agents” in common, each state has its own unique composition in this list of the five most recurring terms.

Finally,

Figure 5 presents a heatmap with the specific counts of each term in the previous list according to all state courts considered in the collection.

The heatmap provides a more comprehensive presentation than what was introduced in

Figure 4, detailing the number of occurrences of each term. It can be noted, for example, that the most recurrent term in any court was “Publicization” in TJ-RS, followed by “Sensitive personal data” in TJ-SP. The term DPO (the acronym for Data Protection Officer) appears in third place overall, with 253 occurrences in TJ-RJ. The terms “Privacy” in TJ-RS and “Data processing” in TJ-PR appear in third and fourth place as the most recurring terms in a court within the presented framework.

3.1. Study Implications

The primary implication of legal data mining at the level executed in this study, based on documents retrieved through a web scraping process on a specialized platform and based on jurisprudence related to the General Data Protection Law (LGPD), is that it is possible to analyze and visualize how the associated results are distributed among Brazilian state courts and to identify the main occurrences within each state. This allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the paths that legal processes related to data protection issues take in the studied regions, particularly in the Brazilian states.

Moreover, analyzing legal documents can direct preventive data protection actions and help understand society’s main problems in this area. Legal data mining also highlights the concentration of jurisprudence on data protection in southeast and southern Brazil, reflecting their greater economic activities involving data from various sources and, consequently, a greater predisposition to generate issues associated with the use and protection of data, which may lead to legal proceedings.

3.2. Future Directions

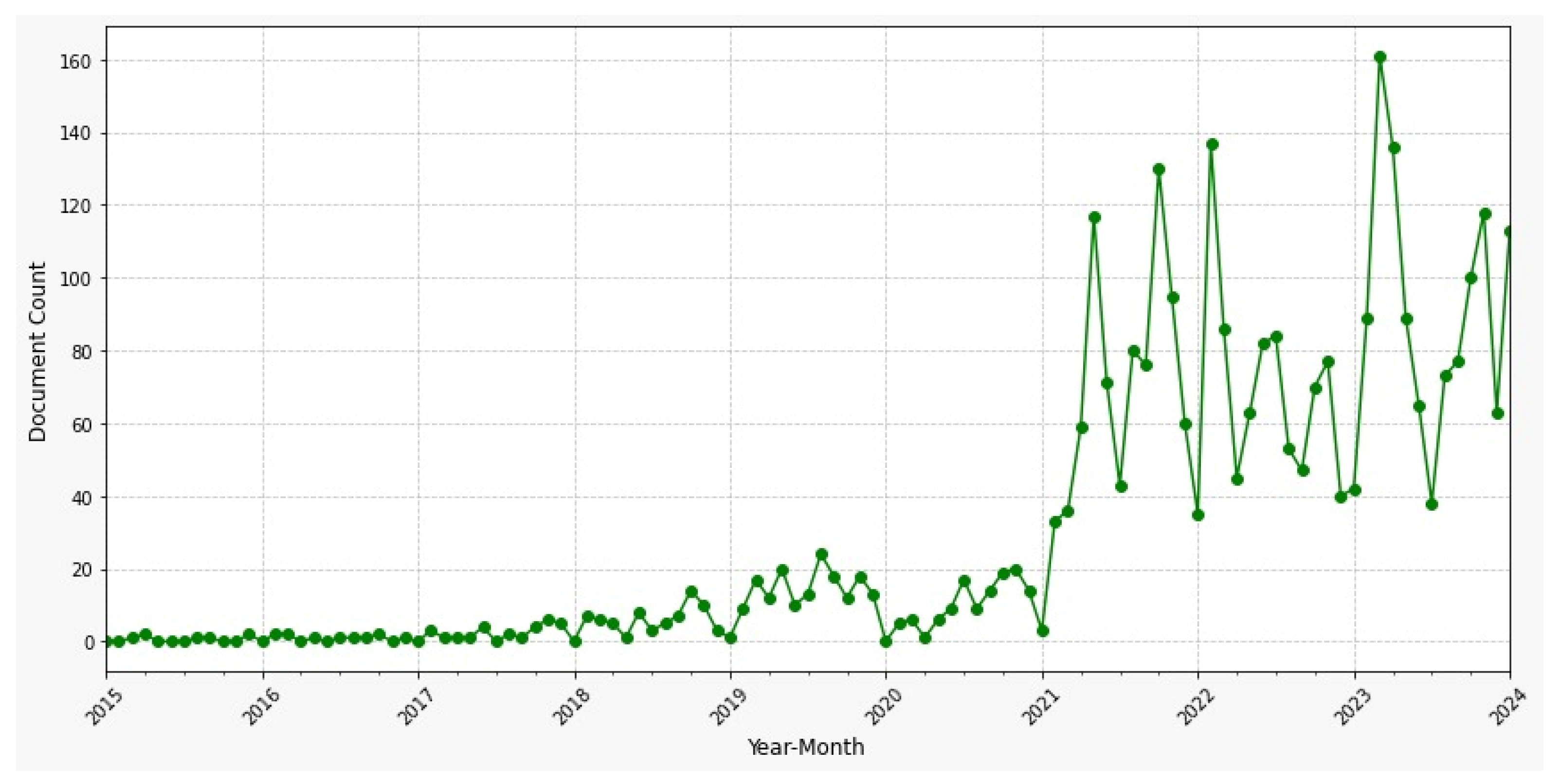

A potential direction to be worked on in the continuation of this study is the analysis of the evolution of jurisprudence over time in Brazil, taking as a focal point of observation the date of promulgation of the Brazilian LGPD to observe its evolution before and after the law came into force. As an example of what can be built,

Figure 6 shows a graph with the evolution of legal documents according to a scraping on the JusBrasil platform.

The graph of the temporal evolution of the number of documents presented above still does not reflect the total number of documents that can be collected. The retrieval of these documents has encountered some technical difficulties, making it impossible to recover all the dates by now. The graph above was extracted according to 4587 documents that could be retrieved with date information.

Profiling jurisprudence according to its spatiotemporal distribution [

14,

15] can contribute to the development of new studies more focused on the profiling of data protection jurisprudence in a specific state or according to a market segment using named entity-recognition extraction processes. Analyzing legal documents can direct preventive data protection actions and help in understanding society’s main problems in this area. This may include identifying gaps in law enforcement and the need for more effective policies to protect users’ data.