1. Introduction

City boundaries are significant points in the spatial structure of a region. City boundary monuments not only function as physical markers, but also as symbols of the identity and culture of a region [

1]. In this context, the concept of placemaking is a design approach that emphasizes the creation of meaningful spaces for the community. This approach is relevant in designing city boundary monuments, which can articulate local values and strengthen the emotional connection between residents and their environment [

2,

3].

Placemaking in boundary monument design is not just about visual esthetics, but also accommodates social interactions, spatial experiences, and the symbolic values that are to be conveyed [

4], and enables the establishment of a space that is passed through by many people. Boundary monuments need to serve as more than just landmarks; they should also be points of orientation that give visitors and locals a sense of the area’s identity [

1]. As placemaking theory progresses, it is crucial for designers to consider social, cultural, and historical aspects to create public spaces that are valuable in the long term and relevant locally [

4].

Recent studies have underscored the significance of placemaking initiatives in developing public spaces, especially along metropolitan edges. A skillfully constructed city border monument may instill local pride and serve as a remarkable visual landmark, particularly when it is created in an authentic location and is founded on the awareness that places are inextricably linked to cultural values that have been tested by human interaction over millennia [

5]. City boundary monuments can act as a bridge between the past and the future, reflecting the history and culture of the local community, as well as their aspirations for regional development.

2. Placemaking of the City Boundary Monument in Surakarta

Surakarta City is a major city in Central Java Province. Between 1945 and 1950, Surakarta was designated as a special region, as outlined in the Presidential Decree Charter of 19 August 1945, and Law No. 1 of 1945 regarding the Status of the Regional National Committee. The city is home to two grand palaces: the Kasunanan Hadiningrat Palace and the Mangkunegaran Palace. These palaces contribute to Surakarta’s reputation as a city steeped in history and traditional wisdom.

Surakarta City has transformed into a hub for tourism, arts, culture, and gastronomy. This transformation is evidenced by the impressive outcomes of the Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy’s Indonesian Tourism Marketing Appreciation (APPI) initiative. Surakarta’s efforts to become a tourist hotspot are directed by Regional Regulation No. 5 of 2017 concerning the Implementation of Tourism Businesses. This regulation has expedited more focused, cohesive, and enduring regional development projects. Surakarta is a city of memories that has left its unique impact on anybody who has visited. One strategy for improving the impression of Surakarta is to organize the road corridor and establish a city border monument to serve as a landmark. The city boundary monument in Mojosongo, which was under construction in 2023, signifies the city’s boundary with Karanganyar Regency. Situated in Mojosongo, the monument stands in an area known for its dense population and dynamic growth in education, industry, commerce, and various public spaces.

Figure 1 is a map of Surakarta and the location of the Mojosongo city boundary monument, which is the object of discussion in this research.

The city boundary monument stands in a public area. Public spaces must serve their essential purpose as responsive, democratic, and significant environments [

6]. Public spaces are a crucial element in the development of high-quality urban environments. Enhancing the connection between people and public spaces can elevate the quality of these areas [

7]. A public space, such as a city square, is an area characterized by specific qualities and ambiance [

8]. Moreover, it is believed that understanding the interactions between the environment and the humans who partake in activities necessitates a sense of place. A place possesses unique characteristics and ambiances pertinent to its context. Consequently, the atmosphere may seem tangible due to elements like materials, appearance, texture, color, or intangible aspects that reflect the culture and practices of the people in its vicinity [

9].

In some communities, city boundary monuments become significant landmarks. These boundary monuments are frequently designed to highlight the characteristics or identity of the area around the municipal boundary monument, aiding in recognition and memory of the region. Landmarks also act as reference points for mental mapping, facilitating the connection of places and simplifying navigation. While city boundary monuments seem to be unique to Indonesia, in other countries, territorial entry is often marked not by distinctive monuments but merely by words on a signboard along the roadside. In larger nations, city boundaries are not marked by monuments but by landmarks or significant markers that represent a city or region.

Figure 2 illustrates various city boundary monuments found across Indonesia.

This article investigates placemaking in the design of the city boundary monument in Mojosongo Surakarta, with a focus on how well the design elements adhere to the placemaking assessment parameters utilized. Several theories underpin this placemaking assessment approach, which has parameters set by the Project for Public Space [

10]. The assessment results in a percentage of conformance with placemaking principles, which provide insight into how much the city boundary monument contributes to supporting local identity and increasing social interaction. Thus, the design of the Mojosongo city boundary monument will be analyzed and explored in greater depth from the standpoint of philosophy and strong cultural concepts.

3. Materials and Methods

Boundary monuments are boundary markers that define two or more territories, such as national, state, and subnational boundaries. Boundary monuments are typically used to indicate a boundary between provinces, districts, cities, villages, or smaller sub-regions.

This study will examine research materials that include a design for the city boundary monument in Mojosongo Surakarta. The analysis or evaluation will be conducted based on the assessment parameters provided by the Project for Public Spaces entity [

10], which states that a location is deemed suitable if it considers various aspects such as physical, cultural, and social sustainability. The assessment encompasses four key factors:

Access and linkage: A location is deemed effective if it facilitates physical and visual interaction with its surroundings. A successful public space should be readily accessible and navigable by the public, and possess a distinct and recognizable appearance.

Comfort and image: Enhancing the visuals in a public area is crucial for public understanding. Additionally, security, comfort, cleanliness, and restroom availability are essential in fulfilling the comfort and image standards set by the Project for Public Spaces (PPS) guidelines.

Uses and activities: The presence of activities is a key factor in attracting people to visit and utilize the amenities provided. Therefore, the utility of these activities is crucial in preventing a space from becoming deserted or neglected by the community.

Sociability: Public space becomes more significant to the community when there is a sense of place, fostering an environment where community members can welcome each other based on sociability. Consequently, this leads to a stronger attachment to the area.

Data collection was actively carried out over a period of one week. Information was gathered from field observations within the surrounding area, including designs of city boundary monuments, for research purposes. Data on actual field conditions, population mobility, community socio-culture, and historical context are essential to assess potential and guarantee sufficient accommodation. The analysis utilized a descriptive quantitative method to evaluate indicators of public space quality as outlined in the book “

Re-framing Urban Space” [

11].

Table 1 and

Table 2 present the assessment parameters and measurable variables:

The placemaking assessment indicator’s evaluation criteria draw from the Quality Urban Space Framework detailed in the book “

Re-framing Urban Space,” focusing on assessment parameters that use public space quality indicators. Scores are allocated based on the placemaking component to evaluate the City Limit Monument’s placemaking quality. This study used a four-value category assessment to determine the extent to which placemaking is used, and the category and value are excellent (value 4), fair (value 3), bad (value 2), and very bad (value 1). Consequently, the maximum score achievable is 52 (13 variables x score of 4), and the minimum is 13 (13 variables × score of 1).

Figure 3 illustrates the data collection, processing, and assessment procedures.

4. Results and Discussion

According to Prasandya, et al. [

6] the location of city boundary monument in Mojosongo, Surakarta, was chosen based on observation and interview. Mojosongo is adensely populated area that actively developing education, industry, trade, and a variety of public areas. This situation must be accommodated in accordance with its essential role as a responsive space. Mojosongo’s public space is a critical component in developing a high-quality urban environment. Public space can let people connect with one another and with nature [

7]. The feeling of space in Mojosongo’s public space, with the city boundary monument serving as an icon with specific qualities, generates a meaningful atmosphere for its surrounding. The quality analysis of the six placemaking variables: interface, accessibility, attraction, activity, amenity and identity. It is shown in the following six tables (

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8), which are explained in detail using 15 assessment indicators.

4.1. Interface

The first aspect assessed is the interface. This aspect assesses the appearance around the monument, and the activities that are synchronized with each other (see

Table 3).

Table 3.

Interface quality aspect.

Table 3.

Interface quality aspect.

| Analysis | Score |

|---|

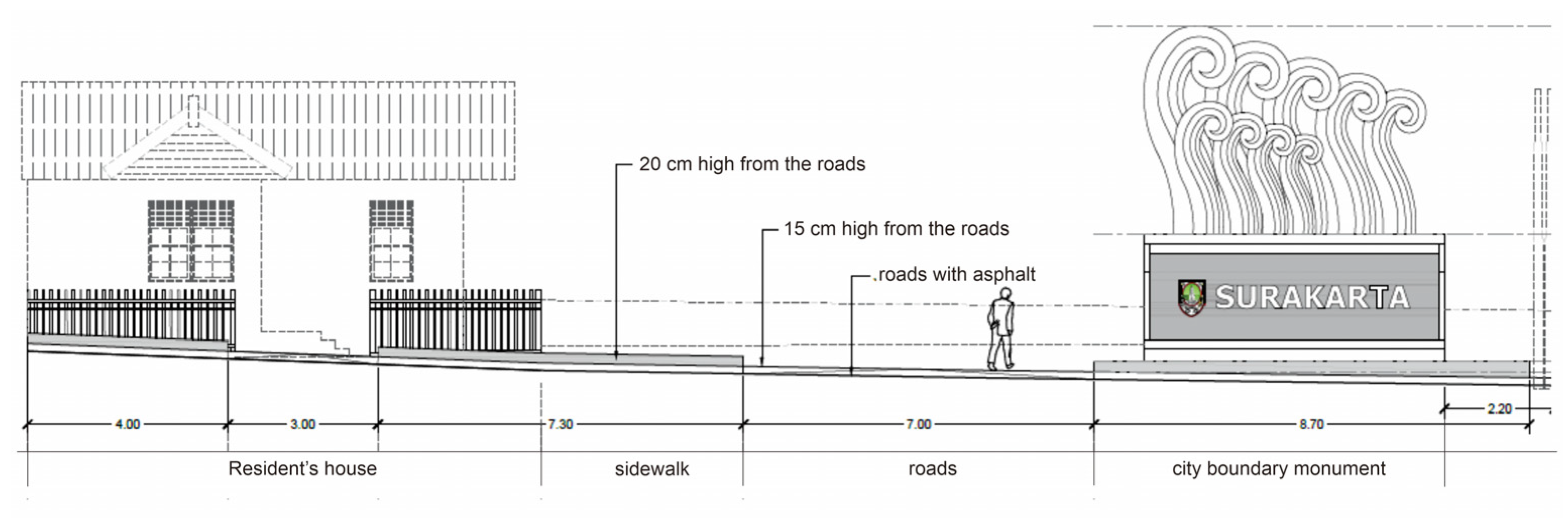

| The city boundary monument area is equipped with pedestrian pathways and is adjacent to strategic routes, facilitating frequent pedestrian traffic (see Figure 4 and Figure 5) | 4 |

- 2.

Spatial Movement

There is a pedestrian route equipped with guiding blocks. The height of the pedestrian area is 30 cm. The pedestrian walkway is furnished with a kawung batik motif that offers cultural visualization value to users | 4 |

- 3.

Sightline and Wayfinding

- ▪

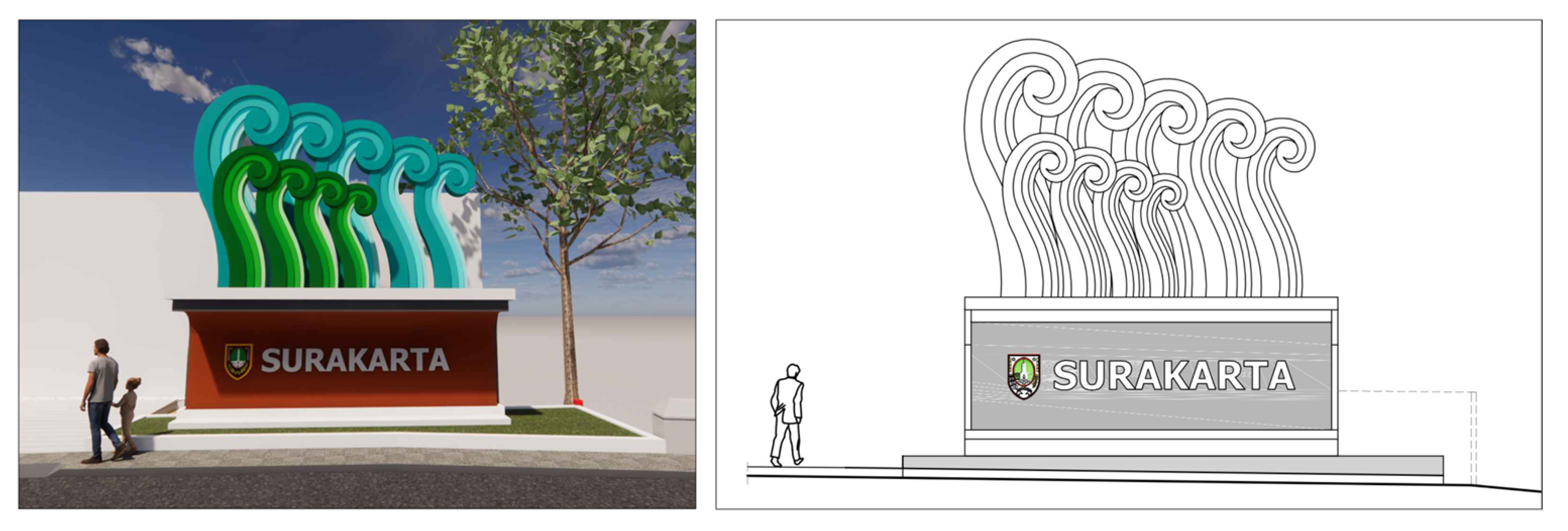

The city’s boundary is adorned with a parang motif and bears the inscription “SURAKARTA.” The parang motif features an uninterrupted S-shape, symbolizing continuity, perseverance, and an unyielding spirit. This symbolism aligns with the historical narrative of the Mojosongo area, where the palace was established as a residence for the empress and her consorts (see Figure 6). - ▪

The visualization of the city boundary monument design is quite captivating, given the monument’s substantial width (6 m) and height (6.7 m), making the city boundary monument appear imposing and majestic to the public.

| 2

4

|

Figure 4.

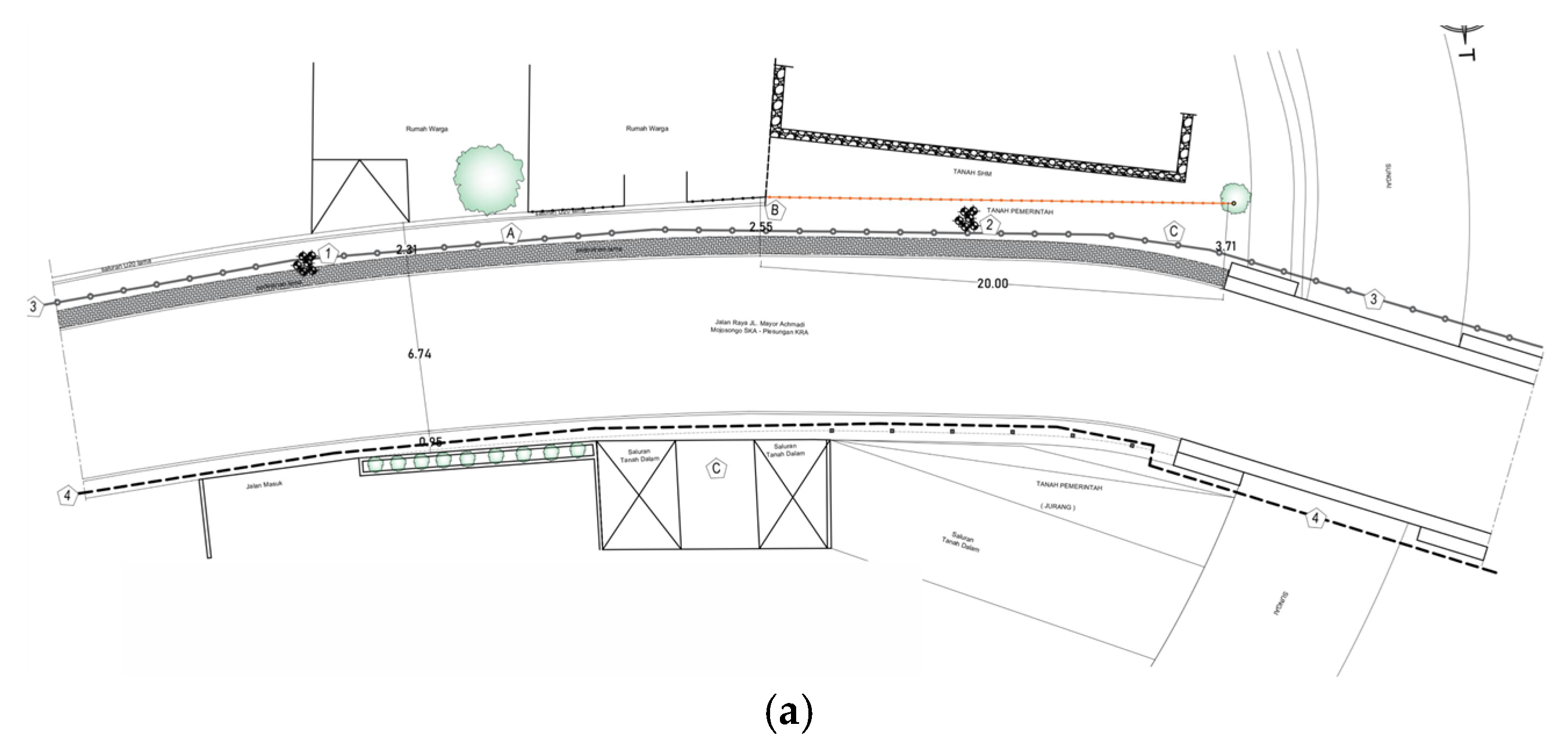

(a) The existing site plan of the city boundary monument location, (b) the site plan of the city boundary monument plan, and (c) a photo of the location of the planned construction of the city boundary monument in Mojosongo Surakarta.

Figure 4.

(a) The existing site plan of the city boundary monument location, (b) the site plan of the city boundary monument plan, and (c) a photo of the location of the planned construction of the city boundary monument in Mojosongo Surakarta.

Figure 5.

Location of city boundary monument in relation to environment.

Figure 5.

Location of city boundary monument in relation to environment.

Figure 6.

The Parang pattern featured on the city boundary monument in Surakarta, characterized by its interconnected ‘S’ shape.

Figure 6.

The Parang pattern featured on the city boundary monument in Surakarta, characterized by its interconnected ‘S’ shape.

4.2. Accessibility

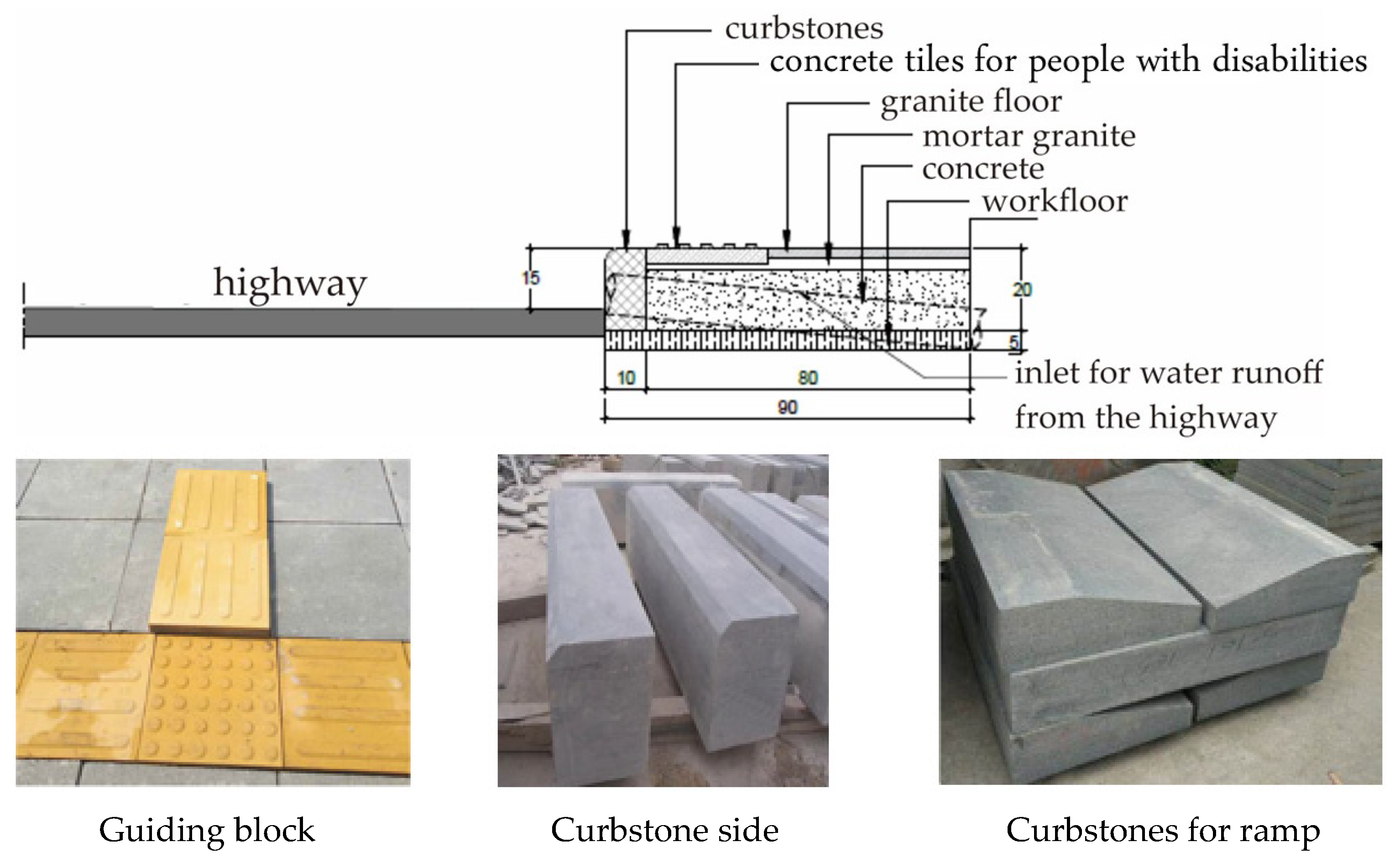

The second concern pertains to accessibility, affecting community mobility and the execution of activities such as transit and walking, in addition to commercial and cultural events near the boundary monument. The Detailed Engineering Design (DED) indicates that the pavement design fulfills the necessary standards to facilitate the activities of people with disabilities (refer to

Figure 7). The quality analysis of indicators up to the assessment is explained in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Accessibility quality aspect.

Table 4.

Accessibility quality aspect.

| Analysis | Score |

|---|

| Pedestrian facilities include walkways designed for community events, constructed with user-friendly materials. These pathways provide easy access to the Mojosongo city boundary monument. | 4 |

- 2.

Utilities

Additionally, guide bricks and ramp curbs are installed on the walkways to facilitate easier boarding and exiting for individuals with disabilities | 4 |

4.3. Attraction

The object’s appeal to users is achieved by the arrangement of space and landscape.

Table 5 summarizes and explains the quality of detailed spatial and landscape variables at Mojosongo city boundary monument.

Table 5.

Attraction quality aspect.

Table 5.

Attraction quality aspect.

| Analysis | Score |

|---|

|

| In spatial planning, pedestrian pathways are situated on both the right and left sides of the main road, enabling safe and clear usage by people (see Figure 8). Guide bricks and ramped curbs with a specific slope are installed to facilitate access for individuals with disabilities | 4 |

- 2.

Landscape

|

- ▪

According to the Detailed Engineering Design (DED), the landscape layout is quite impressive. It includes designated spaces for plants and ample lighting in the pedestrian areas. The materials for pedestrian pathways are color-coded according to their function, with yellow indicating disability guide blocks.

| 4 |

- ▪

The DED’s stage section mentions plants, specifically yellow broccoli. Local plants have been selected to enhance the recognition of the region’s native flora. However, the reasons for choosing yellow broccoli were not thoroughly detailed (see Figure 9).

| 2 |

Figure 8.

The pedestrian area and the city boundary monument from both the right and left perspectives.

Figure 8.

The pedestrian area and the city boundary monument from both the right and left perspectives.

Figure 9.

Cross-sectional image of the pedestrian and a detailed cross-section of the area showing location of LED lights, yellow broccoli plants, fertile soil, and bricks.

Figure 9.

Cross-sectional image of the pedestrian and a detailed cross-section of the area showing location of LED lights, yellow broccoli plants, fertile soil, and bricks.

4.4. Activity

The placemaking activity entails identifying the types of activities that the Mojosongo city boundary monument can accommodate (

Table 6). The monument’s capacity to support a diverse array of activities has been assessed. As per the DED image, the Mojosongo Boundary Monument complies with hardscape criteria and can act as a hub for user activities.

Table 6.

Activity quality aspect.

Table 6.

Activity quality aspect.

| Analysis | Score |

|---|

| Hardscape elements like pedestrian walkways, lighting fixtures, and stage designs can offer shade to visitors. The hardscape materials used for the Mojosongo city boundary monument hold significant value for the community. Regarding softscape materials, the design of the city boundary monument incorporates only yellow broccoli plants between its tiers (see Figure 9). Consequently, the softscape materials in the Mojosongo city boundary monument’s design provide limited benefits to the community or users. | 3 |

4.5. Amenity

The concept of amenity impacts the usefulness of nearby features in terms of safety and service to users. The provided facilities and services are designed to enhance the comfort and satisfaction of users.

Figure 10 illustrates the form of the monument, which does not yet provide comfort for people. The monument appears massive, but the protective and shade features are not yet optimized. The monument is already in the shape of a shelter, although it is not ideal for comfort. When it rains heavily, the shade cannot shield users from the rainfall. Similarly, the shade against direct sunshine appears to be insufficient.

Table 7 shows the analysis that there is no other shade in the form of plants; therefore, it will remain hot during the day. Lighting at night is planned. The lamps strategically place the lights below and above to ensure users’ security and safety. Regarding trash disposal services, there is still built-up household garbage in the current location, and the placemaking design does not include a waste disposal solution.

Table 7.

Amenity quality aspect.

Table 7.

Amenity quality aspect.

| Analysis | Score |

|---|

| There is no shade in the pedestrian area to protect against the scorching sun or rain. The present geography is not flat, but rises and falls. Plant-based shading elements are not ideal for pedestrians because they are on the boundary with residents’ houses. | 3 |

- 2.

Safety and Security

There is a curbstone on the pedestrian walkway that separates it from the road. The curbstone is made of pavement blocks. The pedestrian walkways are also equipped with guide blocks to improve safety for those with disabilities. | 4 |

- 3.

Service

There is no plan for the placement of a waste dump. Meanwhile, there is trash on the pedestrian side of the existing area. The presence of garbage piles has an impact on the area’s appearance. | 1 |

4.6. Identity

The identity parameter is a visible and clearly understood item inside the community. The assessment of identity is based on the criteria of the item’s image, history, and culture, all of which are included in the city boundary monument object.

Table 8 explain the analysis of identity quality; it consists of image as well as historical and cultural symbol.

Meanwhile, the city boundary monument is designed using batik with a parang pattern. Batik with a Parang design is one of the oldest batik motifs and is commonly used in formal clothes. Solo batik with a Parang theme is distinguished by the interlaced and unbroken letter S, which represents continuity and connectivity. For Javanese people, the letter S motif, which resembles waves, represents an eternal soul (

Figure 11).

Table 8.

Identity quality aspect.

Table 8.

Identity quality aspect.

| Analysis | Score |

|---|

| The city boundary monument has the shape of a parang pattern, which is quite recognizable to the Indonesian people. Parang patterns can improve the image of a city boundary memorial item. However, the history and culture of the area surrounding the piece do not yet provide context for the choice of the parang pattern form. | 3 |

- 2.

Historical and Cultural Symbol

The pedestrian path’s kawung batik-patterned paving material reflects historical and cultural values. This theme is derived from the city of Surakarta and represents perfection, purity, and sanctity, as well as the beginning of human existence. | 3 |

5. Discussion

Building a physical identity for an area by integrating people into its design can boost their attachment to the location, improving the quality of urban life [

12]. The physical character of the Mojosongo city boundary monument in Surakarta does not entirely reflect the physical identity of the area. Community engagement in the placemaking process has not resulted in strong place attachment during the redevelopment of public areas. The community is not fully involved. The design is based on the result of a one-sided survey and only involved a few stakeholders. Public hearings are still lacking, so this will almost certainly not improve the quality of life of the community. Placemaking encourages individuals to rediscover the social and cultural significance of public spaces in their communities, as well as to reject private interest groups’ dominant position and influence on public policy. According to Saptorini [

13], comprehensive community participation is required to boost the prospects for placemaking. Awareness of the significance of self-organized community assets, such as the cityscape, local enterprises, intangible values, and customs, will boost architectural and building heritage’s position as a placemaking basic concept. Essentially, placemaking is a collaborative process in which users of a place design and modify their public spaces or the local community, which is supposed to result in stronger emotional attachment to the region [

14]. According to Sebastiani [

15], the role of archeology is to portray the authenticity of comprehending historical monuments in order to help people understand and appreciate cultural assets. The long history of Surakarta’s batik culture is elevated and visualized in the form of a city boundary monument in the shape of a parang batik motif, with certain areas of the floor also displaying a kawung motif. The parang pattern represents continuity and connectivity, as well as an ever-present spirit. The kawung pattern represents a reminder of its roots, ensuring that it remains self-aware and modest.

Since its inception in the 1970s, placemaking has developed into a crucial planning tool that cuts across disciplines, regions, and ideologies [

16]. In the placemaking planning process, cross-disciplinary thinking is a crucial factor. In order to provide the community with a sense of belonging, doing, and making, the Mojosongo city boundary monument was analyzed using the following methodologies: history, culture, architecture and behavior, psychology, and participatory methods. A survey of the pressing community requirements for the design of public areas surrounding the city boundary monument was conducted using the community participatory technique [

17]. It is impossible to use unstructured interviews as a guide for the analytic process, much less to determine the outcomes. The idea behind placemaking for innovative public areas like the MBlock Space in Jakarta is adaptive reuse, which turns unused areas into functional areas.

The results of the analysis of the Mojosongo city boundary monument placemaking, which tries to identify the quality of public space based on assessment parameters based on the Quality Urban Space Framework, can be seen in

Table 9.

Placemaking is evaluated on a four-point scale, with 13 characteristics considered. The assessment resulted a total score of 43 out of a maximum of 52. Thus, the percentage of successful plaque production was as follows:

The placemaking quality score was 82.69%, which is deemed high. Several Quality Urban Space Framework-related parameters have been met. However, there are a few aspects that require extra care. The parameters that have not been reached and require improvement are in service management. The fundamental issue is the lack of a well-designed residential waste or garbage disposal facility. To improve the environment, the government and local communities must work together. Shade areas that are not yet functioning adequately to give protection from heat and rain, as well as the layout of the city boundary being adjacent to residential areas, are two parameters that garner a lot of attention.

6. Conclusions

Placemaking has progressed from a concept introduced in the 1970s to an important planning tool for addressing the urban dilemma and improving urban life. Placemaking is a collaborative process in which place users design and modify their public places, resulting in increased emotional attachment to the area. Successful placemaking can foster a strong emotional bond between users and a place, which is influenced by the location’s identity and the user’s experience, thus improving the quality of urban life.

The quality of urban living can be evaluated using historical values. The Mojosongo area was once part of the Mangkunegaran Palace’s dominion; hence, the historical culture and art of Mojosongo and the Mangkunegaran Palace are very similar. As a result, it would be preferable if the city boundary monument could enhance the image of the Mangkunegaran Palace, highlighting the area’s history and identity. The placemaking design in Mojosongo seems to need additional facilities that emphasize historical values so that it can attract visitors. For example, by designing a cultural gallery building, people will be more interested in getting to know Surakarta better when they are on the city’s boundary or when they enter the city. On the other hand, of course, the service parameters in placemaking must also be strictly observed. The area requires the presence of service zoning with the placement of a trash area that is clearly signposted but slightly hidden, so that it is not too clearly visible from the public zone, and where it is not visible from the highway. Place where people pass by, city boundary markers, or regions near city boundary markers that are claimed as public areas, therefore they must be appealing and have no objectionable views. The most important thing is when establishing placemaking anywhere, it is critical to involve the community from the start. Both policymakers and the entire community must have their voices heard. Community involvement from the outset will improve the environment, especially if the community is given the responsibility for managing their environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R.S. and Y.M.P.; methodology, Y.M.P.; software, N.R.S.; validation, Y.M.P. and N.R.S.; formal analysis, N.R.S.; investigation, Y.M.P.; resources, N.R.S.; data curation, Y.M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.R.S.; writing—review and editing, N.R.S.; visualization, N.R.S.; supervision, N.R.S.; project administration, N.R.S.; funding acquisition, N.R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Frangulea, M.-M. URBAN IDENTITY Highlighting the Landmarks—The Tale of One City. In Proceedings of the 11th Smart Cities International Conference (SCIC), Bucharest, Romania, 7–8 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Liu, C.; Qiu, B. Effects of Urban Landmark Landscapes on Residents’ Place Identity: The Moderating Role of Residence Duration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrup, T.; Jackson, M.R.; Legge, K.; McKeown, A.; Platt, L.; Schupbach, J. The Routledge Handbook of Placemaking; Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group): London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ellery, P.; Ellery, J.; Borkowsky, M. Toward a Theoretical Understanding of Placemaking. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2021, 4, 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jelenski, T. Inclusive Placemaking: Building Future on Local Heritage. In Proceedings of the 5th INTBAU International Annual Event 2017, Milan, Italy, 5–6 July 2017; pp. 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasandya, K.D.E.; Satria, M.W.; Nurwasih, N.W. Desain ruang publik masa depan: Studi ruang publik indoor dan outdoor di bali. J. Pengemb. Kota 2023, 11, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibullah, S.; Ekomadyo, A.S. Place-making pada ruang publik: Menelusuri genius loci pada alun-alun kapuan pontianak. J. Pengemb. Kota 2021, 9, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameria, C.; Akbar, R.; PIndrajati, N.; Tjokropandojo, D.S. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Sense of Place Dimensions in the Heritage Context. J. Reg. City Planing 2020, 31, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahnd, M. Model Baru Perancangan Kota Yang Kontekstual: Kajian Tentang Kawasan Tradisional di Kota Semarang dan Yogyakarta Suatu Potensi Perancangan Kota Yang Efektif; Kanisius: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- What Makes a Successful Place? Available online: https://www.pps.org/article/grplacefeat (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Cho, S.; Heng, C.K.; Trivic, Z. RE-FRAMING URBAN SPACE: Urban Design for Emerging Hybrid and High-Density Conditions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-84986-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, M.; Saad, S. Place Attachment as an Outcome pf Placemaking and The Urban Quality of Life. MSA Univ. Eng. J. 2022, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptorini, H. Placemaking in Yogyakarta Riverside Settlements, Indonesia: Problems and Prospects. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Sustainable Built Environment (ICSBE 2018), Banjarmasin, Indonesia, 11–13 October 2018; Volume 280, p. 02004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hes, D.; Santin, C.H. Placemaking Fundamentals for the Built Environment; Palgrave Mcmillan: Victoria, Australia, 2020; ISBN 978-981-32-9624-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, A. Placemaking an Introduction. In Ancient Rome and the Modern Italian State; Cambridge University Press & Assessment: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-009-35410-3. [Google Scholar]

- Keidar, N.; Fox, M.; Friedman, O.; Grinberger, Y.; Kirresh, T.; Li, Y.; Manor, Y.R.; Rotman, D.; Silverman, E.; Brail, S. Progress in Placemaking. Plan. Theory Pract. 2023, 25, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courage, C.; Keown, A.M.; Placemaking, C. Creative Placemaking: Research, Theory and Practice; Routledge (Taylor&Francis Group): London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).