Experimental Study of Flow Around Stepped NACA 0015 Airfoils at Low Reynolds Numbers †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Test Bench and the Wind Tunnel

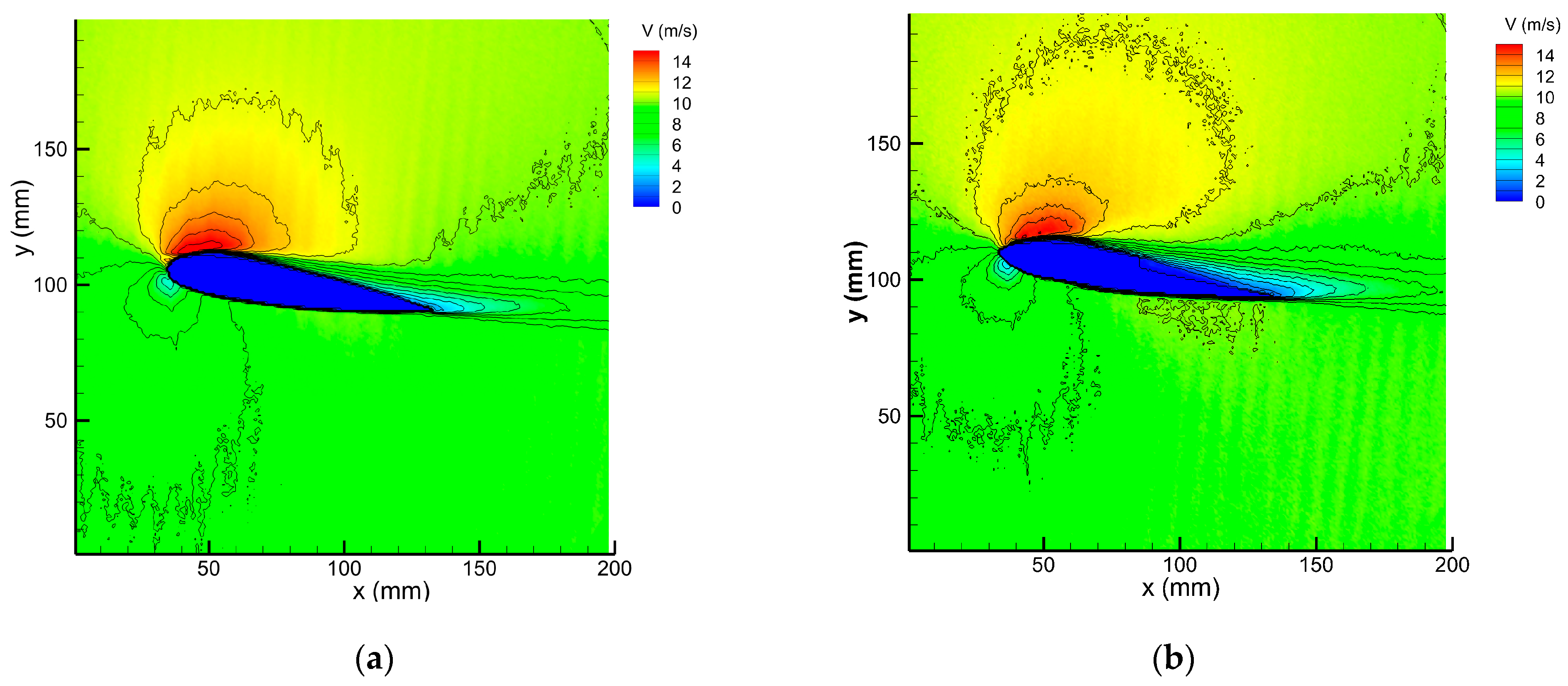

2.1. Wind Tunnel and Measurement Equipment

2.2. Wing Model

3. Methods for Calculating Lift Forces Based on the Velocity Field

3.1. Review of Control Volume Method and Method Based on Kutta-Joukowski Theorem

3.2. Method for Calculating Circulation from PIV Velocity Field

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Selig, M. Low Reynolds Number Airfoil Design Lecture Notes. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Low-Reynolds-Number-Airfoil-Design-Lecture-Notes-Selig/37cd6535639d5da933c5fdf293258f90bf50d7d5#citing-papers (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Carmichael, B.H. Low Reynolds Number Airfoil Survey; No. NASA-CR-165803-VOL-1; National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Langley Research Center: Hampton, VA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow, J.; Otsuka, H.; Govindarajan, B.; Chopra, I. Basic Understanding of Airfoil Characteristics at Low Reynolds Numbers (104–105). J. Aircr. 2018, 55, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.L.; Fogleman, F.F. Airfoil for Aircraft; Google Patents. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US3706430A/en (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- DeLaurier, J.; Harris, J. An Experimental Investigation of the Aerodynamic Characteristics of Stepped-Wedge Airfoils at Low Speeds. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on the Technology and Science of Low Speed and Motorless Flight, Cambridge, MA, USA, 11–13 September 1974; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lumsdaine, E.; Johnson, W.S.; Fletcher, L.M.; Peach, J.E. Investigation of the Kline-Fogleman Airfoil Section for Rotor Blade Applications; The University of Tennessee: Knoxville, TN, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Fertis, D.G. New Airfoil-Design Concept with Improved Aerodynamic Characteristics. J. Aerosp. Eng. 1994, 7, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finaish, F.; Witherspoon, S. Aerodynamic Performance of an Airfoil with Step-Induced Vortex for Lift Augmentation. J. Aerosp. Eng. 1998, 11, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.J.; Avakian, V.; Huynh, B.P. Performance of a Stepped Airfoil at Low Reynolds Numbers. In Proceedings of the 19th Australasian Fluid Mechanics Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 8–11 December 2014; RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kamyab Matin, R.; Ghassemi, H.; Ebrahimi, A.; Ghasemi, B. Experimental Study of Flow Field on Stepped Airfoil at Very Low Reynolds Number. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2017, 231, 1706–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, A.; Coban, M.; Koc, F. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of the Control of the Flow Structure on Surface Modified Airfoils. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2023, 16, 2381–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyhan, M.; Akbıyık, H. An Experimental Investigation on the Flow Control of the Partially Stepped NACA0012 Airfoil at Low Reynolds Numbers. Ocean Eng. 2024, 306, 118068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, A.M.; Gaheen, O.A.; Elshimy, H.; Benini, E.; Aziz, M.A. Bio-Inspired Pressure Side Stepped NACA 23012 C as Wind Turbine Airfoils in Low Reynolds Number. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 3728–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrev, I.; Massouh, F.; Danlos, A.; Todorov, M.; Punov, P. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Flow Field around a Small Car. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 133, 02004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, A.; Mueller, T.J. Effect of Endplates on Two-Dimensional Airfoil Testing at Low Reynolds Number. J. Aircr. 2001, 38, 1056–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moioli, M.; Reinbold, C.; Sørensen, K.; Breitsamter, C. Investigation of Additively Manufactured Wind Tunnel Models with Integrated Pressure Taps for Vortex Flow Analysis. Aerospace 2019, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutilier, M.S.H.; Yarusevych, S. Effects of End Plates and Blockage on Low-Reynolds-Number Flows Over Airfoils. AIAA J. 2012, 50, 1547–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noca, F.; Shiels, D.; Jeon, D. A Comparison of Methods for Evaluating Time-Dependent Fluid Dynamic Forces on Bodies, Using Only Velocity Fields and Their Derivative. J. Fluids Struct. 1999, 13, 551–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oudheusden, B.W.; Scarano, F.; Casimiri, E.W.F. Non-Intrusive Load Characterization of an Airfoil Using PIV. Exp. Fluids 2006, 40, 988–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.H.; Grant, I.; Liu, A.; Infield, D.; Eich, T. The Wind Tunnel Application of Particle Image Velocimetry to the Measurement of Flow over a Wind Turbine. Wind Eng. 1991, 15, 301–317. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.; Su, Y.Y. Low Reynolds Number Airfoil Aerodynamic Loads Determination via Line Integral of Velocity Obtained with Particle Image Velocimetry. Exp. Fluids 2012, 53, 1177–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulven, T.; Bot, P.; Habert, B. Flow Field and Forces on a Highly Curved Plate. In Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Particle Image Velocimetry—ISPIV 2019, Munich, Germany, 22–24 July 2019; Universitat der Bundeswehr Munchen. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Olasek, K.; Karczewski, M. Velocity Data-Based Determination of Airfoil Characteristics with Circulation and Fluid Momentum Change Methods, Including a Control Surface Size Independence Test. Exp. Fluids 2021, 62, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrev, I.; Massouh, F. Method for Extracting Airfoil Data of Rotating Blades. In Proceedings of the 3AF 46th Symposium of Applied Aerodynamics, Orléans, France, 28–30 March 2011; Association Aéronautique et Astronautique de France: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Panayotov, F.; Dobrev, I.; Massouh, F.; Todorov, M. Experimental Study of a Helicopter Rotor Model in Hover. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 234, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mendez, M.A.; Raiola, M.; Masullo, A.; Discetti, S.; Ianiro, A.; Theunissen, R.; Buchlin, J.-M. POD-Based Background Removal for Particle Image Velocimetry. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2017, 80, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, E.N.; Sherman, A. Airfoil Section Characteristics as Affected by Variations of the Reynolds Number. NACA Tech. Rep. 1937, 586, 227–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub, L.W.; Coffman, C. Efficient Low-Reynolds-Number Airfoils. J. Aircr. 2019, 56, 1987–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, İ.; Acir, A. Numerical and Experimental Investigations of Lift and Drag Performances of NACA 0015 Wind Turbine Airfoil. Int. J. Mater. Mech. Manuf. 2015, 3, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Airfoil | Lift Coefficient | Angle of Attack [°] |

|---|---|---|

| NACA 0015 | 0.81 | 10.9 |

| KFm-1 | 0.93 | 13.7 |

| KFm-2 | 0.78 | 8.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dobrev, I.; Pereira, M.; Todorov, M.; Massouh, F. Experimental Study of Flow Around Stepped NACA 0015 Airfoils at Low Reynolds Numbers. Eng. Proc. 2026, 121, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121018

Dobrev I, Pereira M, Todorov M, Massouh F. Experimental Study of Flow Around Stepped NACA 0015 Airfoils at Low Reynolds Numbers. Engineering Proceedings. 2026; 121(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121018

Chicago/Turabian StyleDobrev, Ivan, Michael Pereira, Michael Todorov, and Fawaz Massouh. 2026. "Experimental Study of Flow Around Stepped NACA 0015 Airfoils at Low Reynolds Numbers" Engineering Proceedings 121, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121018

APA StyleDobrev, I., Pereira, M., Todorov, M., & Massouh, F. (2026). Experimental Study of Flow Around Stepped NACA 0015 Airfoils at Low Reynolds Numbers. Engineering Proceedings, 121(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121018