Mine Water Inrush Propagation Modeling and Evacuation Route Optimization †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Analysis

2.1. Problem 1

2.2. Problem 2

2.3. Problem 3

2.4. Problem 4

3. Model Construction

3.1. Assumption

3.2. Water Inrush Flow Propagation Model in Tunnel

- Scenario 1

- Scenario 2

- Water flow distribution: Let the inflow rate at the node be Q. If the node is connected to n branches (horizontal + descending), then the outflow rate for each branch Qout = Qin/n

- Constant initial water level: After splitting, the initial water level in each branch remains 0.1 m. Therefore, the initial cross-sectional area of the branch (S0 = 0.4 m2) remains unchanged, and the propagation time calculation still follows the single tunnel model.

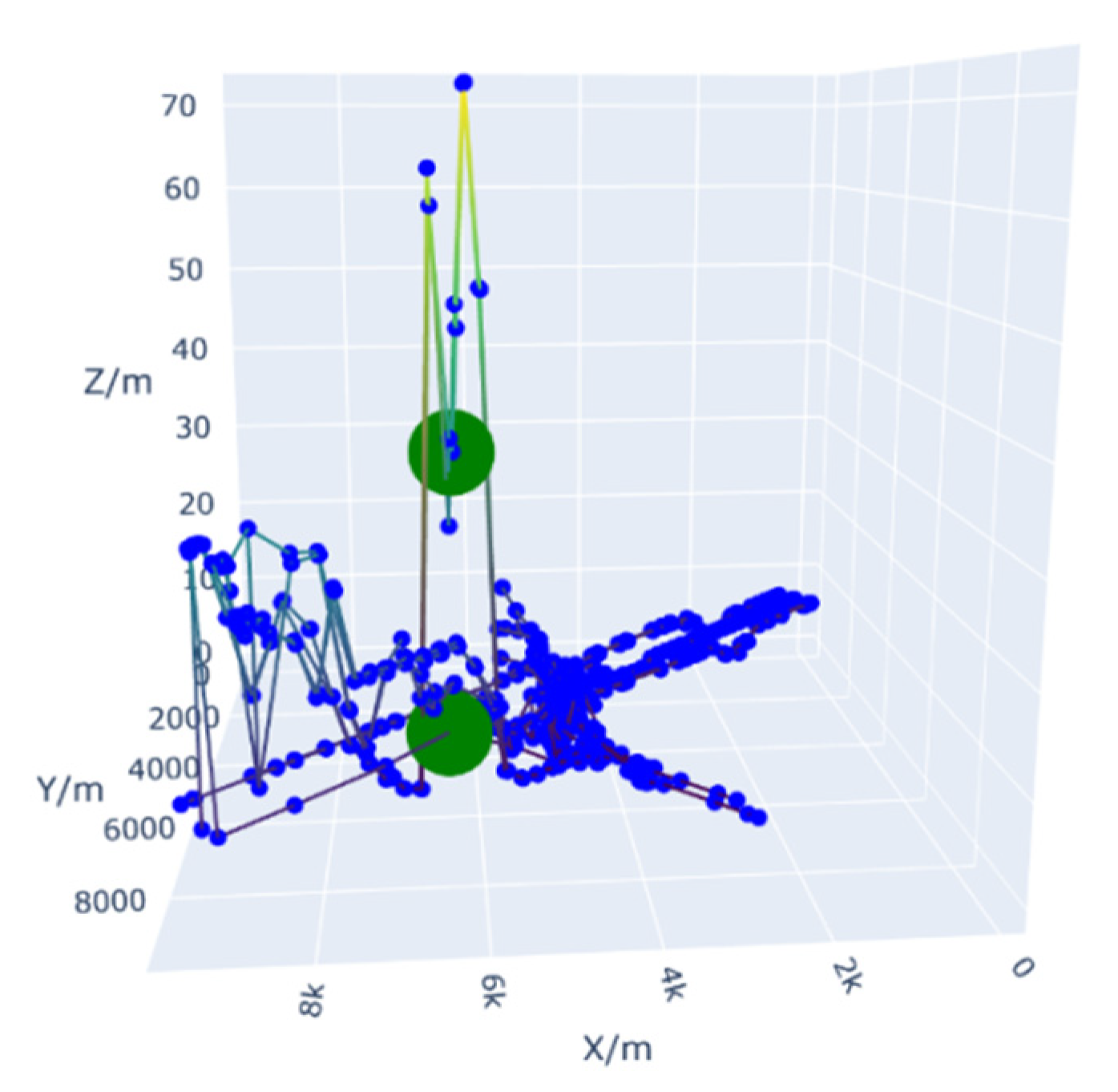

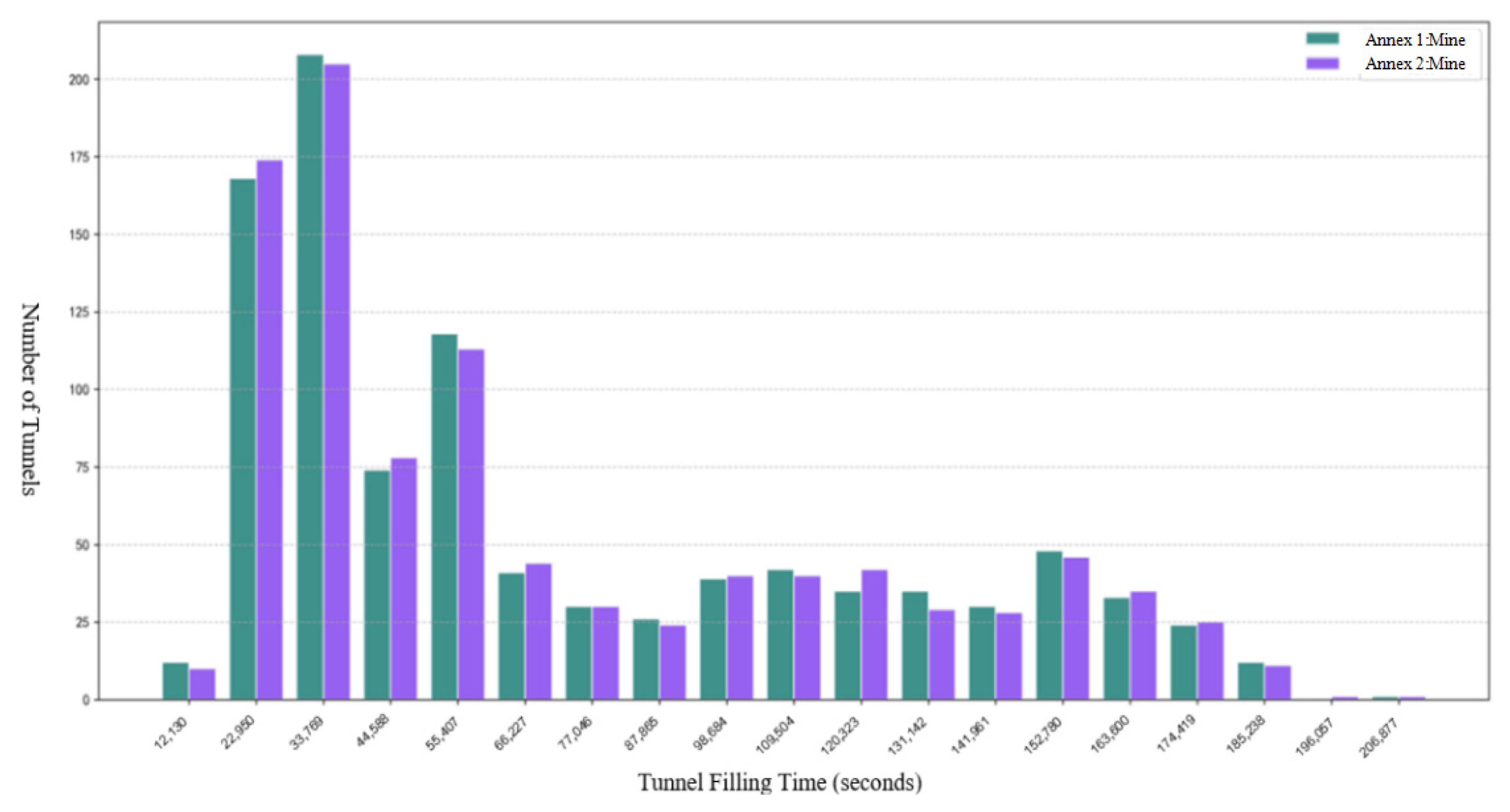

- Time connection: The propagation time for the branch is counted from the time the water flow reaches the node. That is, the branch’s endpoint arrival time = node arrival time + the branch’s own , and the branch’s tunnel filling time = node arrival time + the branch’s own . The flow diffusion process in different time units is simulated by using A1, as shown in Figure 2.

4. Escape Route Planning

4.1. Mine Water Inrush Propagation Model

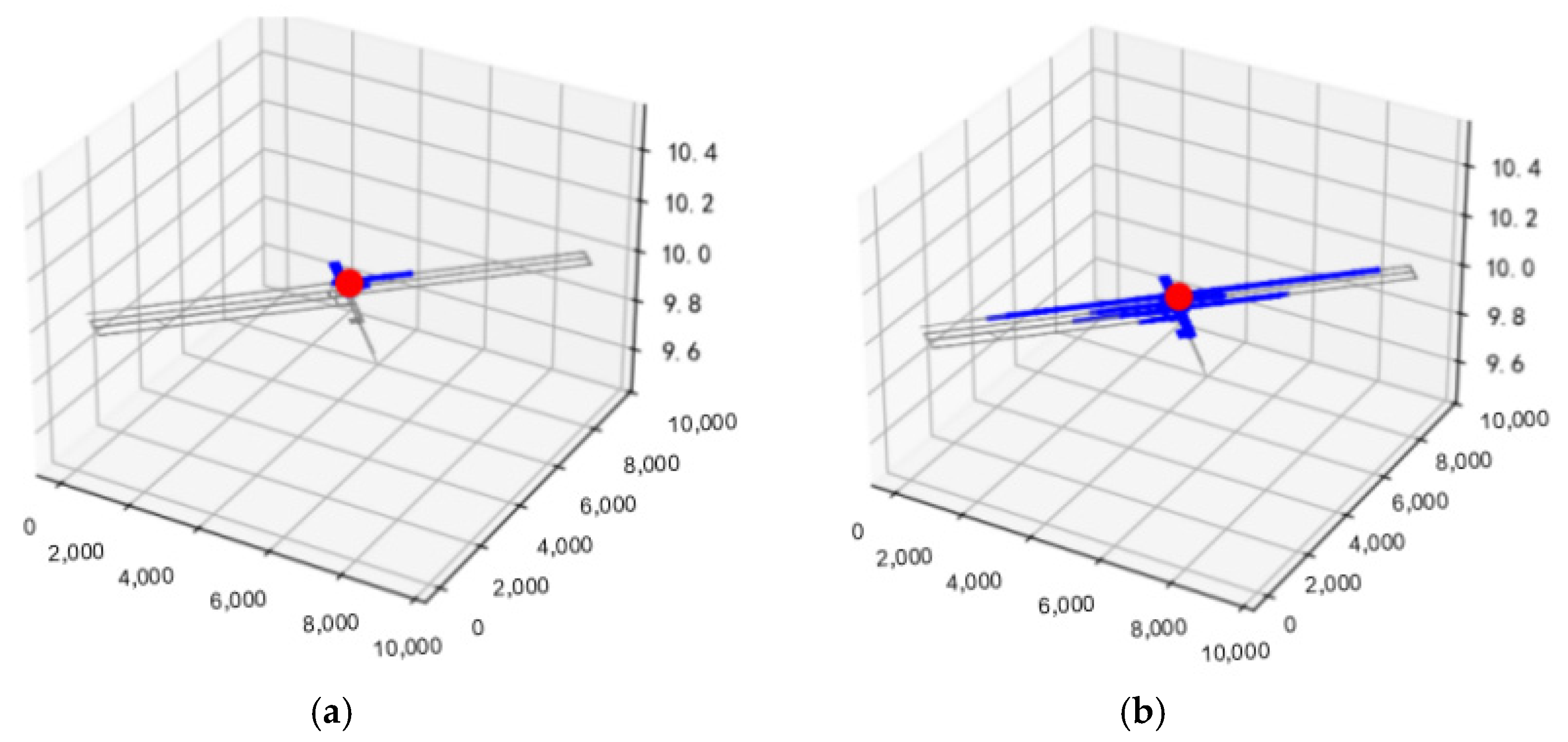

4.2. Dynamic Escape Route Planning Model

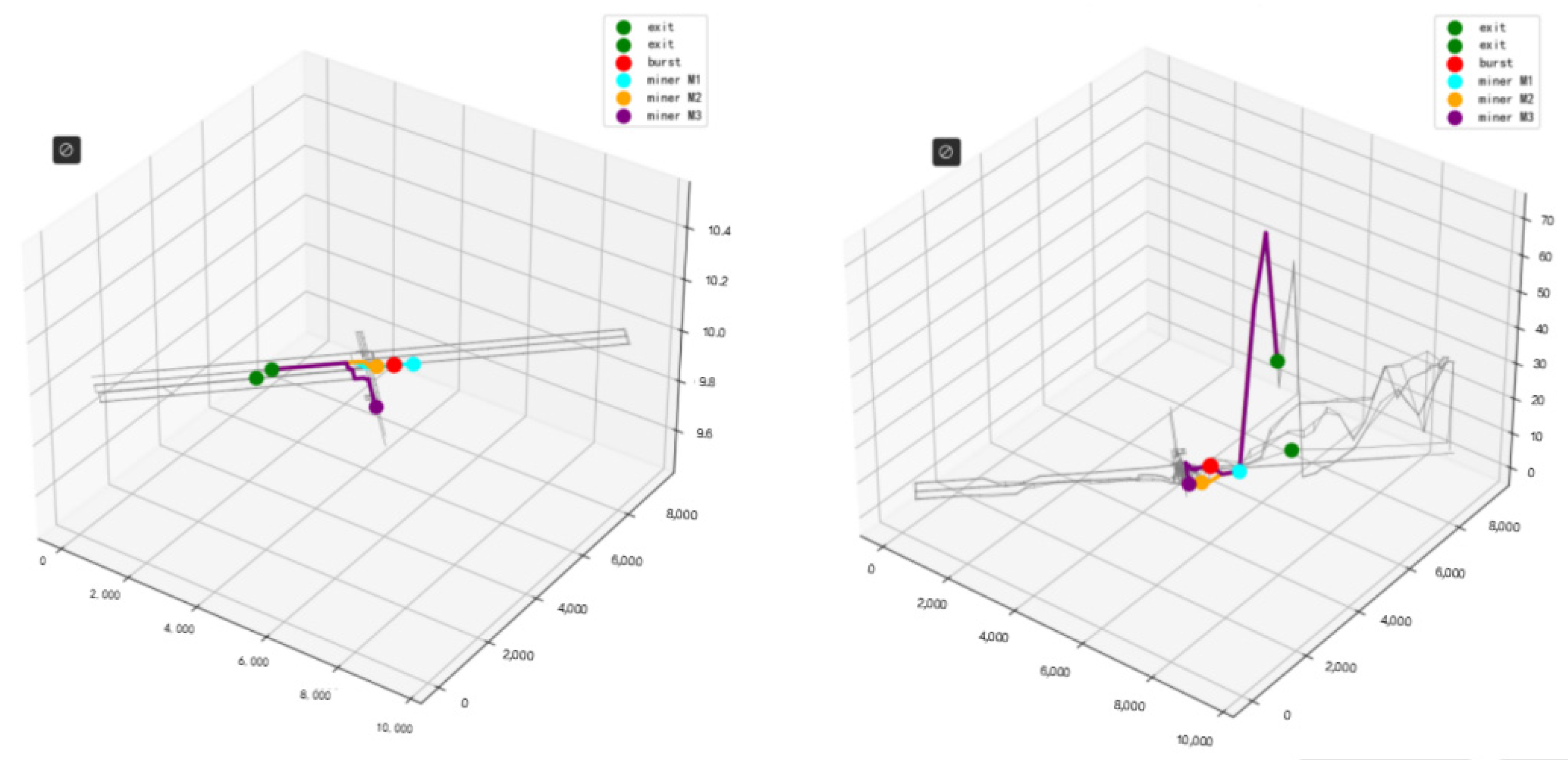

4.3. Water Propagation Model for Multiple Water Inrush Points

4.3.1. Coupling of Three-Dimensional Network Flow and Fluid Dynamics

4.3.2. Dynamic Network Flow Model for Multi-Source Asynchronous Water Inrush

4.4. Adjustment of Escape Routes with Multiple Water Inrush Points

4.4.1. Multi-Objective Evacuation Route Optimization

4.4.2. Dynamic Dijkstra’s Algorithm Based on Time-Expanded Graph (TEG)

- If , the tunnel segment is flooded and impassable.

- If , the tunnel segment is passable, but the water level risk when the miner reaches any point in this segment needs to be calculated.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Sun, B.; Xu, M.; Li, D.; Hu, Y.; Xu, C.; Cui, Y.; Yuan, S. Design and Implementation of an Escape Route Planning System for Deep Mine Water Inrush Based on Graph Structure. China Min. Mag. 2025, 34, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H. Research and Implementation of Simulation Algorithms for Mine Water Inrush and Evacuation. Master’s Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Yan, W.; Li, S. Dynamic Selection of Optimal Escape Path of Mine Water Inrush Based on Weight Time-varying Model. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2022, 22, 4762–4771. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, L.R.; Fulkerson, D.R. Flows in Networks; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Garvishan, A.; Lim, G.J. Dynamic network flow optimization for real-time evacuation reroute planning under multiple road disruptions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safety 2021, 214, 107644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillac, V.; Van Hentenryck, P.; Even, C. A conflict-based path-generation heuristic for evacuation planning. arXiv 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Yang, K.; Zhou, P. A dynamic path planning model for underground mine evacuation considering water diffusion and human behavior. Saf. Sci. 2021, 134, 105068. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, E.W. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numer. Math. 1959, 1, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | t1 | Endpoint arrival time |

| 2 | h0 | Initial water level |

| 3 | Q | Flow rate entering the tunnel |

| 4 | t2 | Time when the tunnel is completely filled |

| 5 | Time when water reaches the endpoint | |

| 6 | Time when the tunnel is filled | |

| 7 | S0 | Initial cross-sectional area of the branch |

| 8 | Initial inflow rate into the tunnel | |

| 9 | Inflow rate | |

| 10 | Flow rate in each branch | |

| 11 | Flow rate at the water inrush point | |

| 12 | If a node has k feasible flow tunnels, the flow rate allocated to each tunnel | |

| 13 | Water volume | |

| 14 | Tunnel capacity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, X.; Wu, H.; Pan, J.; Liu, Y. Mine Water Inrush Propagation Modeling and Evacuation Route Optimization. Eng. Proc. 2025, 120, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025120040

Yu X, Wu H, Pan J, Liu Y. Mine Water Inrush Propagation Modeling and Evacuation Route Optimization. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 120(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025120040

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Xuemei, Hongguan Wu, Jingyi Pan, and Yihang Liu. 2025. "Mine Water Inrush Propagation Modeling and Evacuation Route Optimization" Engineering Proceedings 120, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025120040

APA StyleYu, X., Wu, H., Pan, J., & Liu, Y. (2025). Mine Water Inrush Propagation Modeling and Evacuation Route Optimization. Engineering Proceedings, 120(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025120040