Microstructural Study of Welded and Repair Welded Dissimilar Creep-Resistant Steels Using Different Filler Materials †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Base and Filler Materials

2.2. Welding Process

2.3. Repair Welds and PWHT

2.4. Characterization Techniques

3. Results

3.1. Microstructural Observations

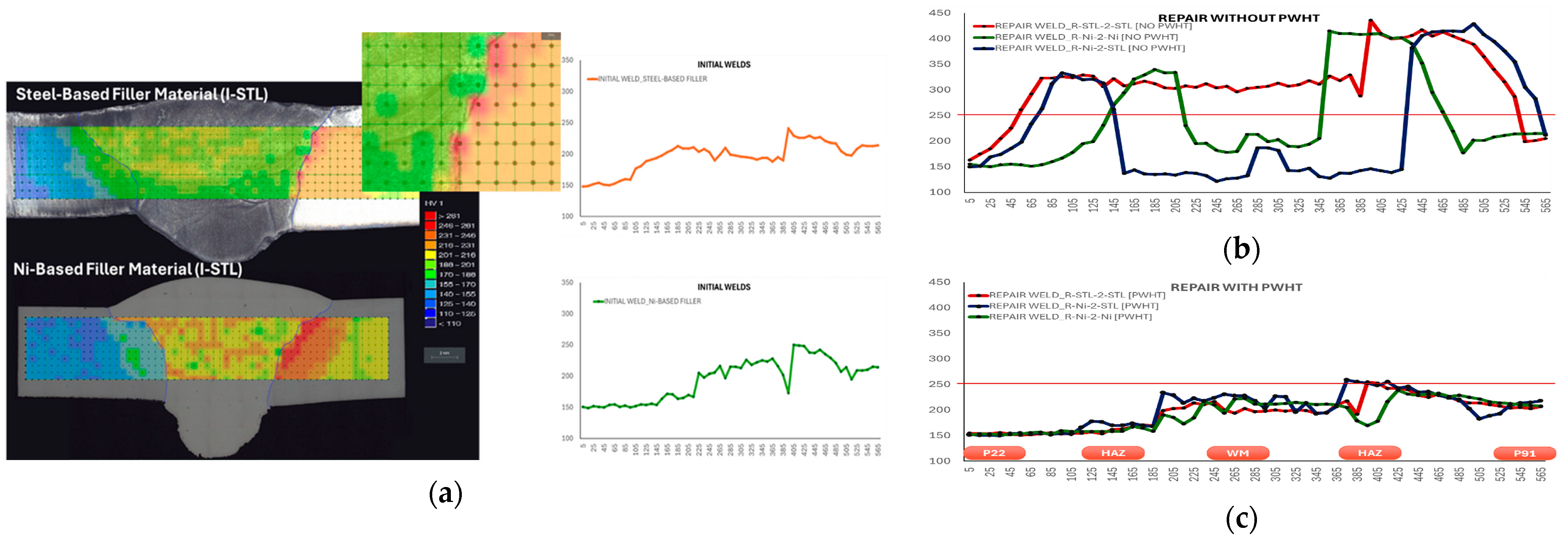

3.2. Hardness Measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saini, N.; Mulik, R.S.; Mahapatra, M.M. Influence of filler metals and PWHT regime on the microstructure and mechanical property relationships of CSEF steels dissimilar welded joints. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2019, 170, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dak, G.; Pandey, C. A critical review on dissimilar welds joint between martensitic and austenitic steel for power plant application. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 58, 377–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Pandey, C.; Goyal, A. A microstructural and mechanical behavior study of heterogeneous P91 welded joint. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 2020, 185, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Che, C.; Qian, G.; Wang, X. Microstructure, hardness and creep properties for P91 steel after long-term service in an ultra-supercritical power plant. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 2024, 212, 105330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Dwivedi, D.K.; Vasudevan, M. Study of mechanism, microstructure and mechanical properties of activated flux TIG welded P91–P22 joint. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 731, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauraw, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Fydrych, D.; Sirohi, S.; Gupta, A.; Świerczyńska, A.; Pandey, C.; Rogalski, G. Study on microstructural characterization, mechanical properties and residual stress of GTAW dissimilar joints of P91 and P22 steels. Materials 2021, 14, 6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayr, P.; Schlacher, C.; Siefert, J.A.; Parker, J.D. Microstructural features, mechanical properties and high temperature failures of ferritic to ferritic dissimilar welds. Int. Mater. Rev. 2018, 63, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, C.; Mahapatra, M.M.; Kumar, P. Fracture behaviour of crept P91 welded sample for different post weld heat treatments condition. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 95, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arivazhagan, B.; Vasudevan, M. Studies on A-TIG welding of 2.25Cr-1Mo (P22) steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2015, 18, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirohi, S.; Gupta, A.; Pandey, C.; Vidyarthy, R.S.; Guguloth, K.; Natu, H. Investigation of the microstructure and mechanical properties of the laser welded joint of P22 and P91 steel. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 147, 107610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Yadav, V.K.; Sharma, S.K.; Pandey, C.; Singh, R.; Gupta, A. Role of dissimilar Ni-based ERNiCrMo-3 filler on microstructure, mechanical properties and residual stresses of P91 welds. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 2021, 193, 104443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, A.; Subramani, P.; Kannan, V.; Shanmugam, N.S. Investigation on microstructure, micro-segregation and mechanical properties of GTA weldment of Alloy 600. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 13244–13250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ji, M.; Xu, L.; Chu, Y. Effect of dendritic structure and secondary phases on the fatigue behavior of ERNiCrMo-3 weld metal. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 180, 108113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.J.; Kumar, P. TIG Welding P22 and P91 Steels: Behavior Analysis and Sustainable PWHT. Master’s Thesis, MM University, Ambala, India, CIPET, Jaipur, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, S.; Chhibber, R. High temperature molten salt corrosion investigations on P22/P91 power plant dissimilar welds. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2020, 234, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidou, D.; Foinikaridis, M.; Deligiannis, S.; Tsakiridis, P.E. Microstructural evaluation of Inconel 718 and AISI 304L dissimilar TIG joints. Metals 2024, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P22 | C | Mn | P | S | Si | Cr | Mo | Other |

| 0.05–0.15 | 0.30–0.60 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.50 max | 1.90–2.60 | 0.87–1.13 | - | |

| P91 | C | Mn | P | S | Si | Cr | Mo | Other |

| 0.08–0.12 | 0.30–0.60 | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.20–0.50 | 8.0–9.5 | 0.85–1.05 | V: 0.18–0.25, N: 0.030–0.070 Ni: 0.40 max, Al: 0.02 max Cb: 0.06–0.10, Ti: 0.01 max, Zr: 0.01 max |

| Passes | Filler Material Size | Current (A) | Voltage (V) | Type of Current/Polarity | Wire Feed Speed | Travel Speed (mm/s) | Heat Input (kJ/mm) | |

Steel-Based Filler Material (I-STL) | 1 | 2.4 | 90.0 | 9.5 | DCEN | Manual | 0.65 | 1.31 |

| 2 | 99.0 | 9.8 | 1.01 | 0.96 | ||||

| 3 | 119.0 | 10.9 | 1.26 | 1.02 | ||||

| 4 | 125.0 | 15.0 | 0.70 | 0.96 | ||||

Ni-Based Filler Material (I-Ni) | 1 | 2.4 | 95.0 | 14.0 | DCEN | Manual | 0.58 | 0.83 |

| 2 | 99.0 | 14.5 | 0.62 | 0.83 | ||||

| 3 | 105.0 | 14.5 | 0.65 | 0.84 | ||||

| 4 | 120.0 | 15.0 | 0.70 | 0.93 |

| Passes | Filler Material Size | Current (A) | Voltage (V) | Type of Current/Polarity | Wire Feed Speed | Travel Speed (mm/s) | Heat Input (kJ/mm) | |

| Steel-Based Filler | 1 | 2.4 | 119.0 | 10.9 | DCEN | Manual | 1.26 | 1.02 |

| 2 | 125.0 | 15.0 | 0.70 | 0.96 | ||||

| Ni-Based Filler | 1 | 2.4 | 105.0 | 14.5 | DCEN | Manual | 0.65 | 0.84 |

| 2 | 120.0 | 15.0 | 0.70 | 0.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chionopoulos, S.; Zervas, A.; Mathioudakis, M. Microstructural Study of Welded and Repair Welded Dissimilar Creep-Resistant Steels Using Different Filler Materials. Eng. Proc. 2025, 119, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119009

Chionopoulos S, Zervas A, Mathioudakis M. Microstructural Study of Welded and Repair Welded Dissimilar Creep-Resistant Steels Using Different Filler Materials. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 119(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119009

Chicago/Turabian StyleChionopoulos, Stavros, Aimilianos Zervas, and Michail Mathioudakis. 2025. "Microstructural Study of Welded and Repair Welded Dissimilar Creep-Resistant Steels Using Different Filler Materials" Engineering Proceedings 119, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119009

APA StyleChionopoulos, S., Zervas, A., & Mathioudakis, M. (2025). Microstructural Study of Welded and Repair Welded Dissimilar Creep-Resistant Steels Using Different Filler Materials. Engineering Proceedings, 119(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119009