Tensile Behavior of Romanian ‘Țurcana’ Sheep Wool Waste-Fibers: Influence of Body Region †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Test Samples

2.2. Structural Characterization and Morphology

2.3. Tensile Testing

3. Results and Discussion

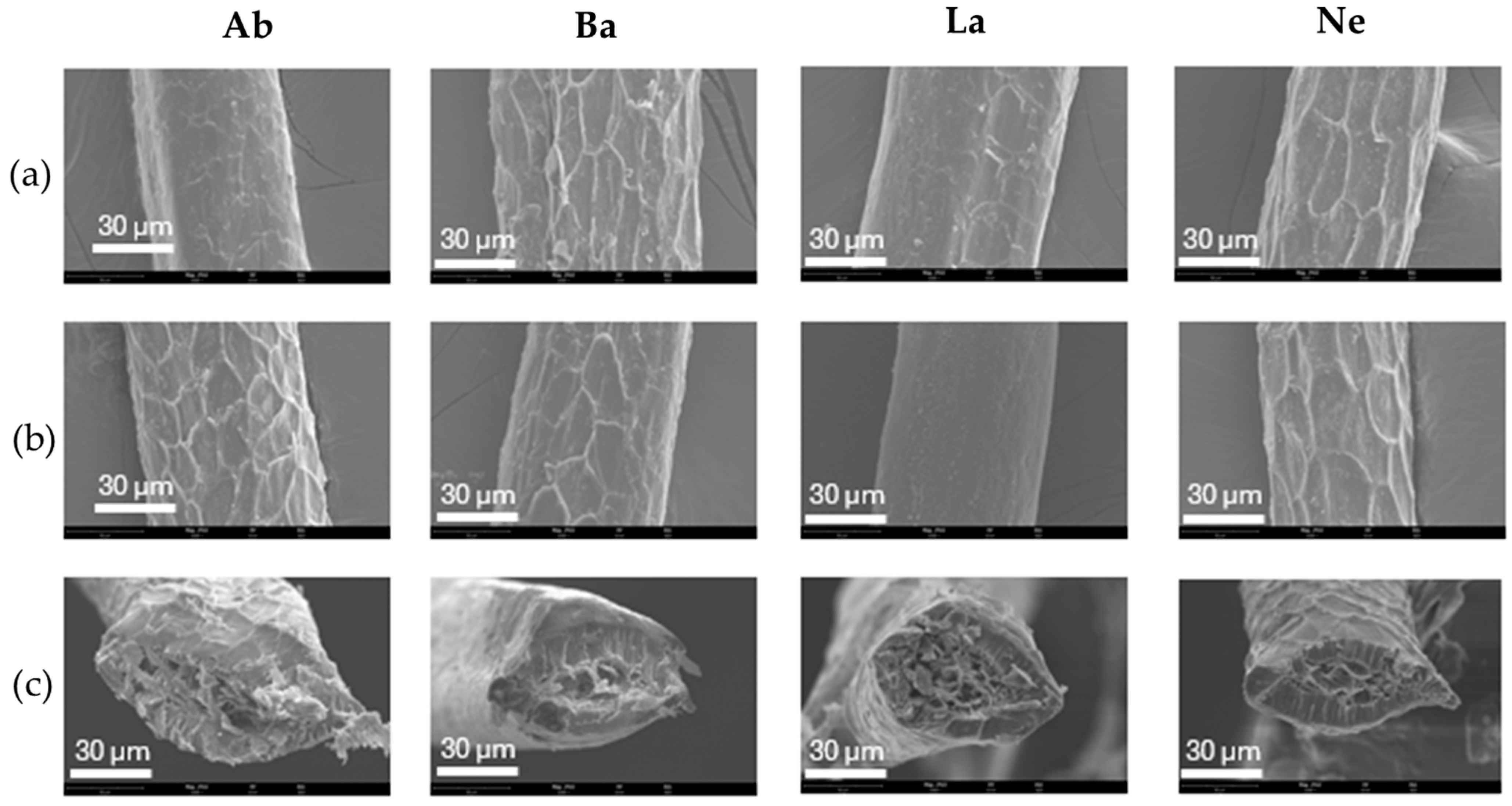

3.1. Scanning Electron Micrographs (SEM)

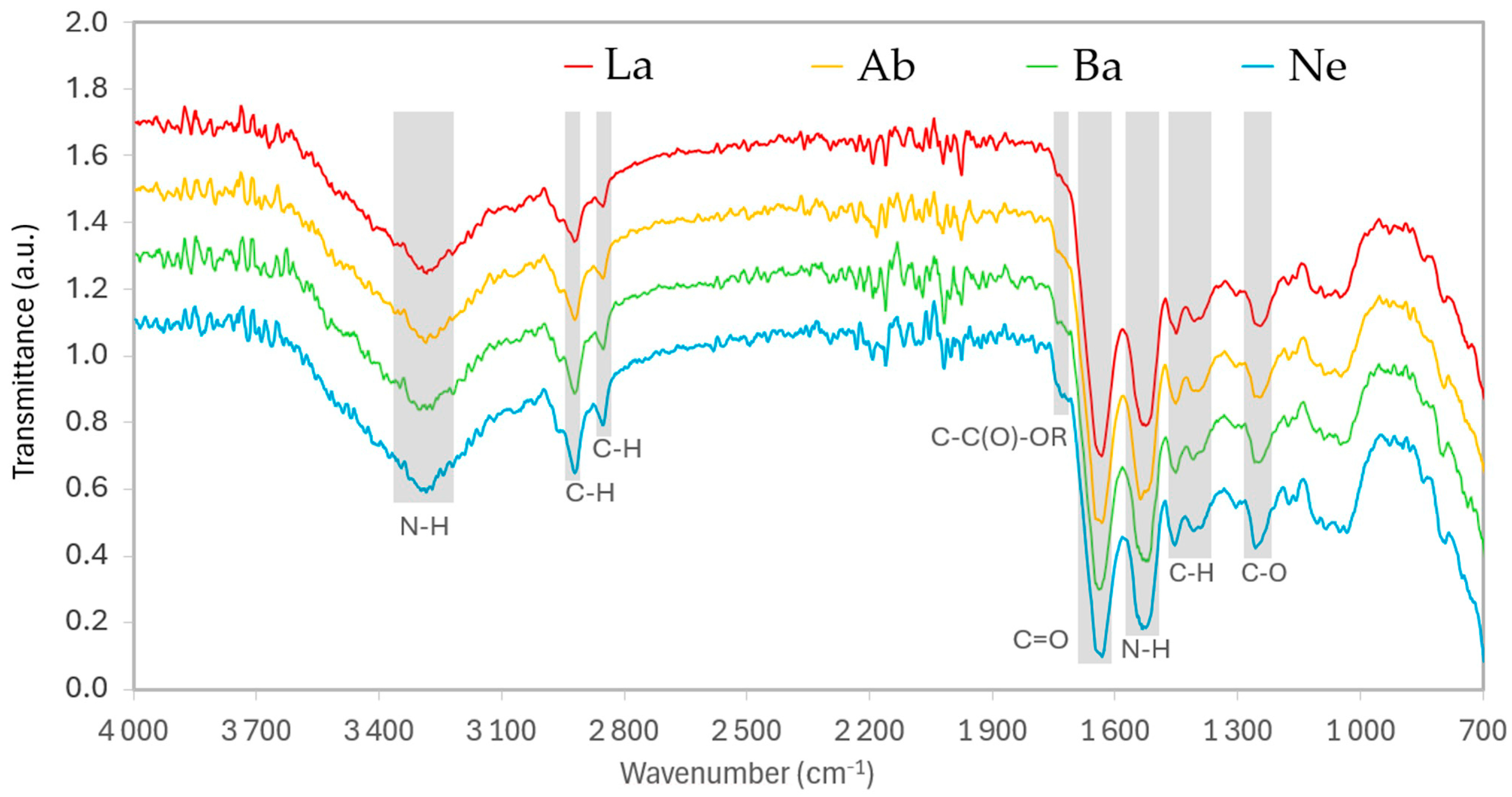

3.2. ATR-FTIR Spectra

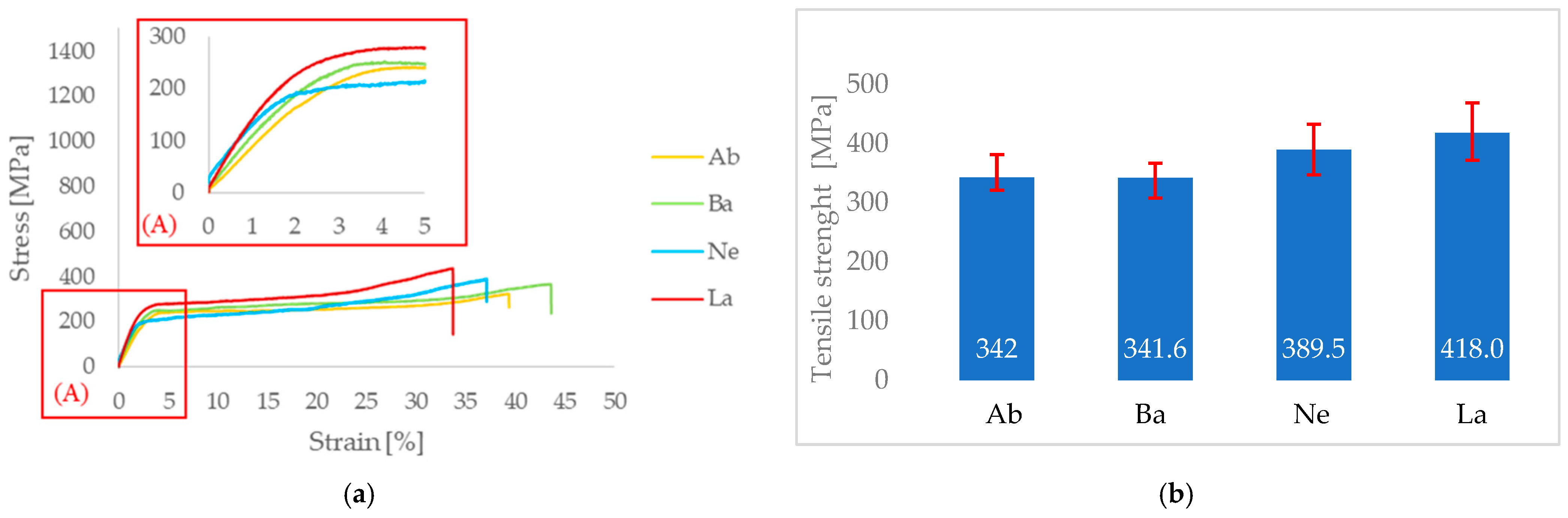

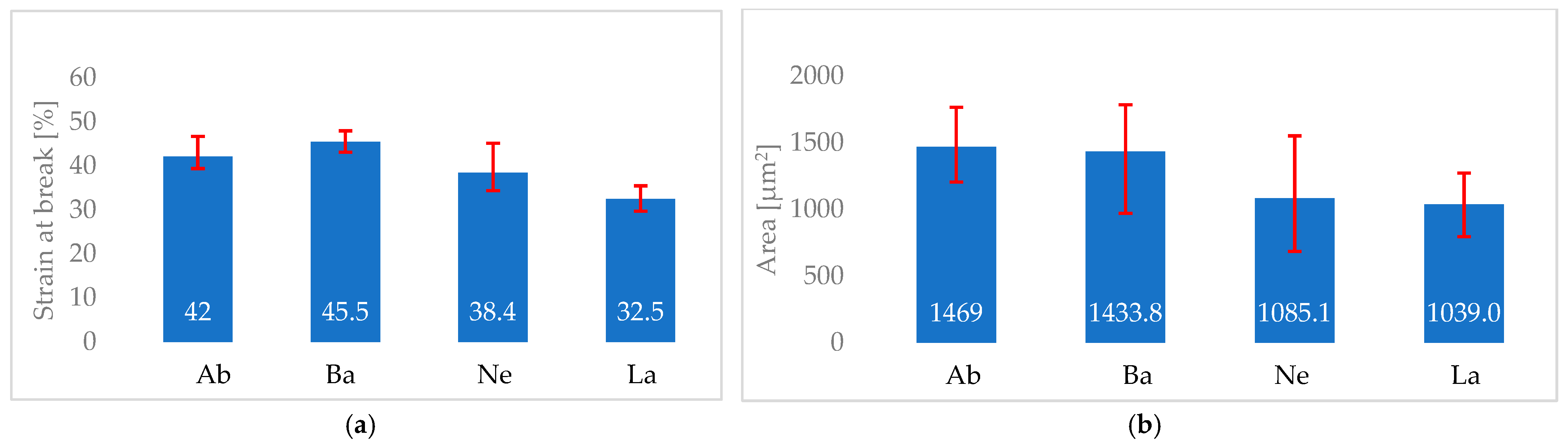

3.3. Tensile Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/1069/oj (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Parlato, M.C.; Porto, S.M.; Valenti, F. Assessment of sheep wool waste as new resource for green building elements. Build. Environ. 2022, 225, 109596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.reportlinker.com/dataset/1ddf31187e58067ffe53896af63077724fb102cf?utm (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Mioč, B.; Džaja, A.; Širić, I.; Kasap, A.; Antunović, Z.; Držaić, V. The Influence of Breed and Body Region on the Wool Fibre Diameter. Poljoprivreda 2025, 31, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janíček, M.; Massányi, M.; Kováčik, A.; Halo, M., Jr.; Tirpák, F.; Blaszczyk-Altman, M.; Massányi, P. Content of Biogenic Elements in Sheep Wool by the Regions of Slovakia. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 1886–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkova, O.; Sabalina, A.; Voikiva, V.; Osite, A. Environmental effects on strength and failure strain distributions of sheep wool fibers. Polymers 2022, 14, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tămaş-Gavrea, D.R.; Dénes, T.O.; Iştoan, R.; Tiuc, A.E.; Manea, D.L.; Vasile, O. A Novel Acoustic Sandwich Panel Based on Sheep Wool. Coatings 2020, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlea, S.I.; Tiuc, A.E.; Nemeş, O.; Vermeşan, H.; Vasile, O. Innovative use of sheep wool for obtaining materials with improved sound-absorbing properties. Materials 2020, 13, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, S.; Shanumon, P.S.; Kadam, V.; Tom, M.; Thomas, S. Preparation, characterisation and application of biodegradable coarse wool-poly (lactic acid) sandwich composite. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 10293–10310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guna, V.; Yadav, C.; Maithri, B.R.; Ilangovan, M.; Touchaleaume, F.; Saulnier, B.; Grohens, Y.; Reddy, N. Wool and coir fiber reinforced gypsum ceiling tiles with enhanced stability and acoustic and thermal resistance. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 41, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousef, R.; Aldossari, K.; Ibrahim, O.; Mustafa, H.; Jabr, A. Effect of sheep wool fiber on fresh and hardened properties of fiber reinforced concrete. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2019, 10, 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Wani, I.A. Experimental investigation on using sheep wool as fiber reinforcement in concrete giving increment in overall strength. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 4405–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlato, M.C.M.; Cuomo, M.; Porto, S.M.C. Natural fibers reinforcement for earthen building components: Mechanical performances of a low quality sheep wool (“Valle del Belice” sheep). Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 326, 126855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.K.; Meena, A.; Sahu, M.; Dalai, A. Experimental investigation on mechanical and thermal characteristics of waste sheep wool fiber-filled epoxy composites. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, K.N.; Manjunatha, G.B.; Santhosh, K. Failure analysis and the optimal toughness design of sheep–wool reinforced epoxy composites. In Failure Analysis in Biocomposites, Fibre-Reinforced Composites and Hybrid Composites; Woodhead Publishing: Davangere, India, 2019; pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Szatkowski, P.; Tadla, A.; Flis, Z.; Szatkowska, M.; Suchorowiec, K.; Molik, E. The potential application of sheep wool as a component of composites. Rocz. Nauk. Pol. Tow. Zootech. 2021, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.S.; Rabbi, M.S.; Ahmed, R.U.; Billah, M.M. Biodegradable natural polymers and fibers for 3D printing: A holistic perspective on processing, characterization, and advanced applications. Clean. Mater. 2024, 14, 100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.N.M.A.; Naebe, M.; Mielewski, D.; Kiziltas, A. Waste wool/polycaprolactone filament towards sustainable use in 3D printing. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, B.A.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.G. Comparisons of thr Fourier Transform Infrared Spectra of cashmere, guard hair, wool and another animal fibers. J. Text. Inst. 2017, 109, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanell, C.B.; Carrer, V.; Marti, M.; Iglesias, J.; Iglesias, J.; Coderch, L. Solvent-extracted wool wax: Thermotropic properties and skin efficacy. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 31, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.N. Intrinsic Strength of Merino Wool Fibres. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Animal Science, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rottenbury, R.A.; Bow, M.R.; Kavanagh, W.J.; Caffin, R.N. Staple strength variation in Merino flocks. Wool Technol. Sheep Breed. 1981, 29, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, D.A.; Meikle, H.E. The processing significance of variations in staple strength within and between fleeces. In Proceedings of the 7th International Wool Textile Research Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 28 August–3 September 1985; pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bouagga, T.; Harizi, T.; Sakli, F.; Zoccola, M. Correlation between the mechanical behavior and chemical, physical and thermal characteristics of wool: A study on Tunisian wool. J. Nat. Fibers 2020, 17, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E. Textile Properties of Wool and Other Fibres; Wool Research Organization of New Zealand: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2003; pp. 272–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sosdean, C.; Galatanu, S.V. Tensile properties of Romanian “Țurcana” sheep wool farm-waste fibers. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 1319, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Pant, S. Properties of camel kid hair: Chokla wool blended yarns and fabrics. Stud. Home Community Sci. 2013, 7, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scobie, D.R.; Grosvenor, A.J.; Bray, A.R.; Tandon, S.K.; Meade, W.J.; Cooper, A.M.B. A review of wool fibre variation across the body of sheep and the effects on wool processing. Small Rumin. Res. 2015, 133, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WF Width per Body Region (µm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back (Ba) | Lateral (La) | Abdomen (Ab) | Neck (Ne) | ||

| Sample | 1 | 37.00 | 40.25 | 45.67 | 42 |

| 2 | 38.83 | 35 | 45.17 | 33.11 | |

| 3 | 45.67 | 34.58 | 41.83 | 44.44 | |

| 4 | 35.17 | 36.75 | 39.17 | 35 | |

| 5 | 46.33 | 31.83 | 44.00 | 29.56 | |

| 6 | 44.67 | 34.25 | 47.42 | 43.22 | |

| 7 | 37.83 | 33.33 | 42.17 | 31 | |

| 8 | 47.67 | 37.75 | 40.67 | 38.11 | |

| 9 | 45.00 | 40 | 39.33 | 36.33 | |

| 10 | 46.75 | 38.92 | 44.83 | 35.78 | |

| Min | 35.17 | 31.83 | 39.17 | 29.56 | |

| Max | 47.67 | 40.25 | 47.42 | 44.44 | |

| Average | 42.49 | 36.27 | 43.03 | 36.86 | |

| Standard deviation | 4.71 | 2.908 | 2.815 | 5.083 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sosdean, C.; Piçarra, S.; Galatanu, S.-V.; Marsavina, L. Tensile Behavior of Romanian ‘Țurcana’ Sheep Wool Waste-Fibers: Influence of Body Region. Eng. Proc. 2025, 119, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119017

Sosdean C, Piçarra S, Galatanu S-V, Marsavina L. Tensile Behavior of Romanian ‘Țurcana’ Sheep Wool Waste-Fibers: Influence of Body Region. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 119(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119017

Chicago/Turabian StyleSosdean, Corina, Susana Piçarra, Sergiu-Valentin Galatanu, and Liviu Marsavina. 2025. "Tensile Behavior of Romanian ‘Țurcana’ Sheep Wool Waste-Fibers: Influence of Body Region" Engineering Proceedings 119, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119017

APA StyleSosdean, C., Piçarra, S., Galatanu, S.-V., & Marsavina, L. (2025). Tensile Behavior of Romanian ‘Țurcana’ Sheep Wool Waste-Fibers: Influence of Body Region. Engineering Proceedings, 119(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119017