Reduction in the Estimation Error in Load Inversion Problems: Application to an Aerostructure †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Mathematical Formulation for the Conversion Matrix Approach

- The applied loads do not lead to non-linear response of the structure; the material response remains within its elastic regime, and thus, superposition can be applied.

- The structure is loaded at a finite number of known locations. The loading direction is also given, leaving their magnitude as the sole unknown variable for evaluation.

- The imposed loads are static or quasi-static, making inertia effects negligible.

- Furthermore, assuming a linear relationship between load and strain such thatin which the αij term is the strain–force proportionality factor, often referred to as “influence” or “calibration “coefficient. Additionally, F is a 1 × nlr vector containing all the load aiming to reconstruct, and A is the ns × nl “conversion matrix” containing the influence coefficients between the strain and the loads.

2.2. Optimal Experimental Designs—D-Optimality

2.3. Genetic Algorithms

2.4. Optimal Sensor Placement (OSP) Design Framework

3. Numerical Analysis and Results

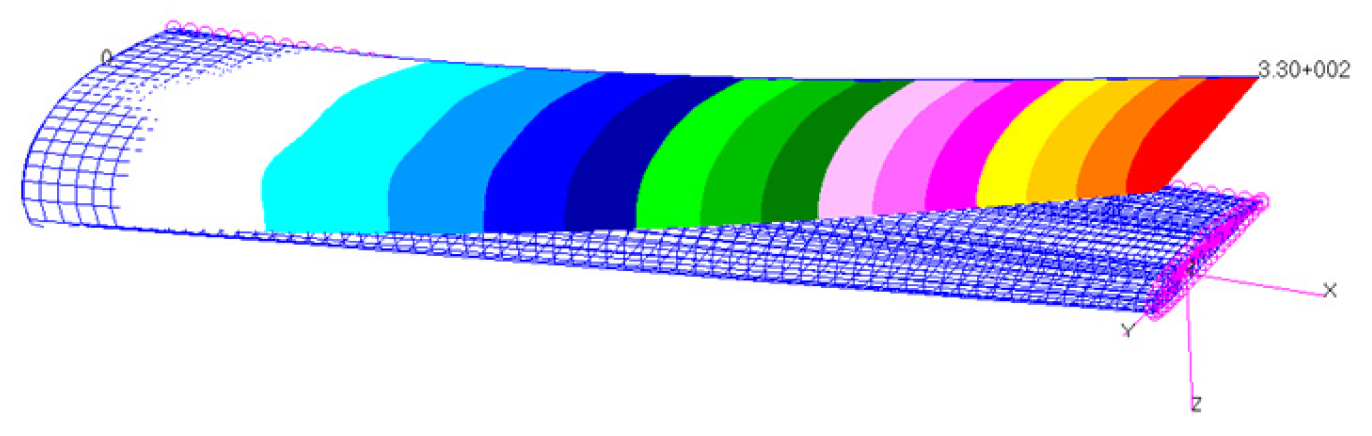

3.1. Model Developement

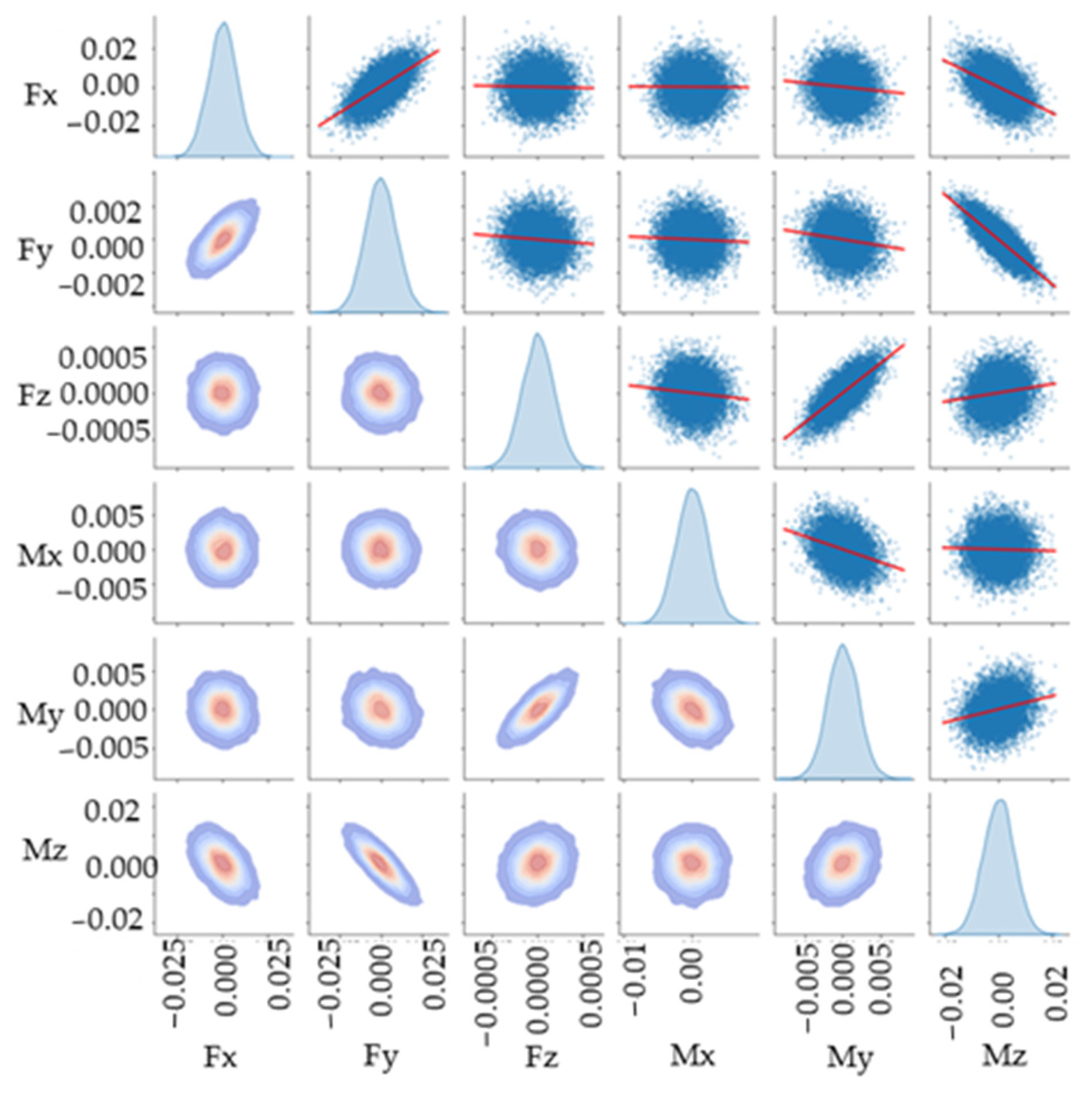

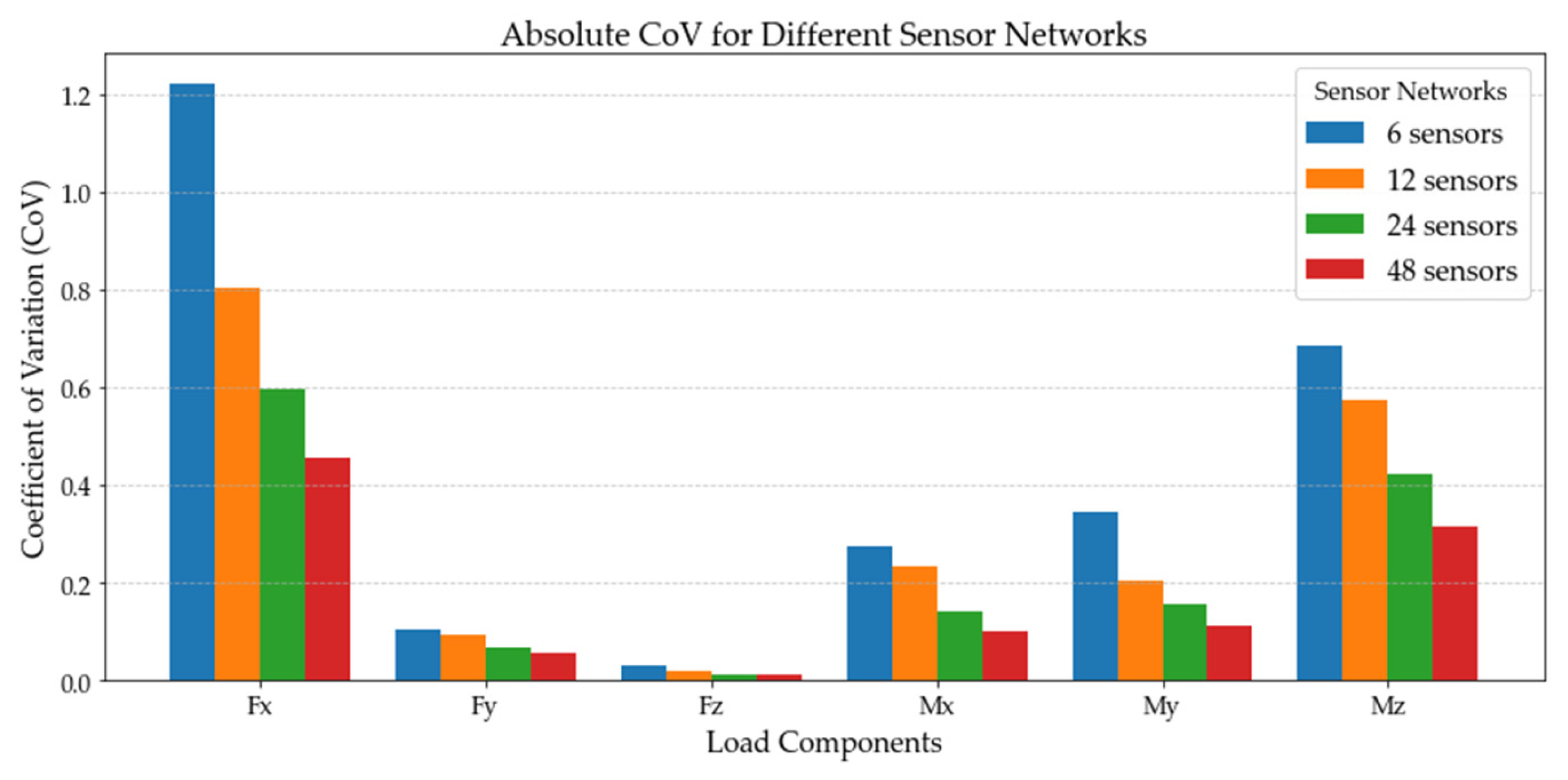

3.2. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colombo, L.; Sbarufatti, C.; Bosco, L.D.; Bortolotti, D.; Dziendzikowski, M.; Dragan, K.; Concli, F.; Giglio, M. Numerical and experimental verification of an inverse-direct approach for load and strain monitoring in aeronautical structures. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2021, 28, e2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, D.; Sugimoto, Y.; Murayama, H.; Igawa, H.; Nakamura, T. Investigation of Inverse Analysis and Neural Network Approaches for Identifying Distributed Load using Distributed Strains. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2019, 62, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, R.; Cross, E.; Halfpenny, A.; Worden, K.; Barthorpe, R.J. Aircraft Parametric Structural Load Monitoring Using Gaussian Process Regression. 2014. Available online: https://inria.hal.science/hal-01022048 (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- He, J.; Zhou, Y.; Guan, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y. Time Domain Strain/Stress Reconstruction Based on Empirical Mode Decomposition: Numerical Study and Experimental Validation. Sensors 2016, 16, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Zhou, Y.; Guan, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. An Integrated Health Monitoring Method for Structural Fatigue Life Evaluation Using Limited Sensor Data. Materials 2016, 9, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sireta, F.-X.; Storhaug, G. A Modal Approach for Holistic Hull Structure Monitoring from Strain Gauges Measurements and Structural Analysis. In Proceedings of the Off-Shore Technology Conference, Houston, TA, USA, 2–5 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboe, D.; Colombo, L.; Sbarufatti, C.; Giglio, M. Shape Sensing of a Complex Aeronautical Structure with Inverse Finite Element Method. Sensors 2021, 21, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gherlone, M.; Cerracchio, P.; Mattone, M.; Di Sciuva, M.; Tessler, A. Shape sensing of 3D frame structures using an inverse Finite Element Method. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2012, 49, 3100–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Mattone, M.; Gherlone, M. Experimental Shape Sensing and Load Identification on a Stiffened Panel: A Comparative Study. Sensors 2022, 22, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Igawa, H.; Kanda, A. Inverse identification of continuously distributed loads using strain data. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2012, 23, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, L.; Sbarufatti, C.; Zielinski, W.; Dragan, K.; Giglio, M. Numerical and experimental flight verifications of a calibration matrix approach for load monitoring and temperature reconstruction and compensation. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 107074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, S.; Anyfantis, K.N. Load identification for fatigue life assessment in ship hull structural elements. In Proceedings of the 10th European Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring (EWSHM 2024), Potsdam, Germany, 10–13 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, M.J.; Riley, D.R.; Nachtsheim, C.J. Integrating Optimal Experimental Design into the Design of a Multi-Axis Load Transducer. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 1995, 117, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.K.; Dhingra, A.K. Input load identification from optimally placed strain gages using D-optimal design and model reduction. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2013, 40, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Law, S.; Yang, Q. Sensor placement methods for an improved force identification in state space. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2013, 41, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, H.; Li, S.; Wu, Z. Inverse Load Identification in Stiffened Plate Structure Based on in situ Strain Measurement. Struct. Durab. Health Monit. 2021, 15, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galil, Z.; Kiefer, J. Time- and Space-Saving Computer Methods, Related to Mitchell’s DETMAX, for Finding D-Optimum Designs. Technometrics 1980, 22, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E. Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization and Machine Learning; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.: Carrollton, TX, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

| STRUCTURAL PART | LAY-UP | TOTAL THICKNESS |

|---|---|---|

| LOWER AND UPPER SKINS | 45w/0_core/45w | 3.44 mm |

| LOWER AND UPPER SPAR CAPS | 45w/45w/0_core/45w/45w/0/0/45w/0/0/45w | 4.92 mm |

| FRONT SPAR WEB | 45w/45w/45w/45w | 0.87 mm |

| REAR SPAR WEB | 45w/45w/0_core/45w/45w | 3.87 mm |

| RIBS | 45w/45w | 0.44 mm |

| # SENSORS | LOAD 1 (FX) | LOAD 2 (FY) | LOAD 3 (FZ) | LOAD 4 (MX) | LOAD 5 (MY) | LOAD 6 (MZ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | mean | 1.4999348 | 1.49999188 | 2.49999928 | −1.9999493 | −1.999978 | −2.0001056 |

| CoV | 1.223113 | 0.1034149 | 0.0293033 | 0.2734192 | 0.3467196 | 0.6844731 | |

| 12 | mean | 1.500077 | 1.4999963 | 2.5000048 | −2.000012 | −2.000012 | −2.000011 |

| CoV | 0.803082 | 0.094592 | 0.0177268 | 0.2346718 | 0.2035107 | 0.5733383 | |

| 24 | mean | 1.50006 | 1.5000135 | 2.4999969 | −1.9999992 | −1.999947 | −1.9998506 |

| CoV | 0.596135 | 0.06899981 | 0.0137325 | 0.1409092 | 0.1572164 | 0.4216038 | |

| 48 | mean | 1.49999 | 1.50000163 | 2.499997 | −2.0000308 | −1.999988 | −2.0000135 |

| CoV | 0.455827 | 0.05536822 | 0.0102288 | 0.1018635 | 0.1104922 | 0.3151355 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panou, G.; Panagiotopoulos, S.G.; Anyfantis, K. Reduction in the Estimation Error in Load Inversion Problems: Application to an Aerostructure. Eng. Proc. 2025, 119, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119015

Panou G, Panagiotopoulos SG, Anyfantis K. Reduction in the Estimation Error in Load Inversion Problems: Application to an Aerostructure. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 119(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119015

Chicago/Turabian StylePanou, George, Sotiris G. Panagiotopoulos, and Konstantinos Anyfantis. 2025. "Reduction in the Estimation Error in Load Inversion Problems: Application to an Aerostructure" Engineering Proceedings 119, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119015

APA StylePanou, G., Panagiotopoulos, S. G., & Anyfantis, K. (2025). Reduction in the Estimation Error in Load Inversion Problems: Application to an Aerostructure. Engineering Proceedings, 119(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119015