Impact of Electrical Noise on the Accuracy of Resistive Sensor Measurements Using Sensor-to-Microcontroller Direct Interface †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Simulation Setup

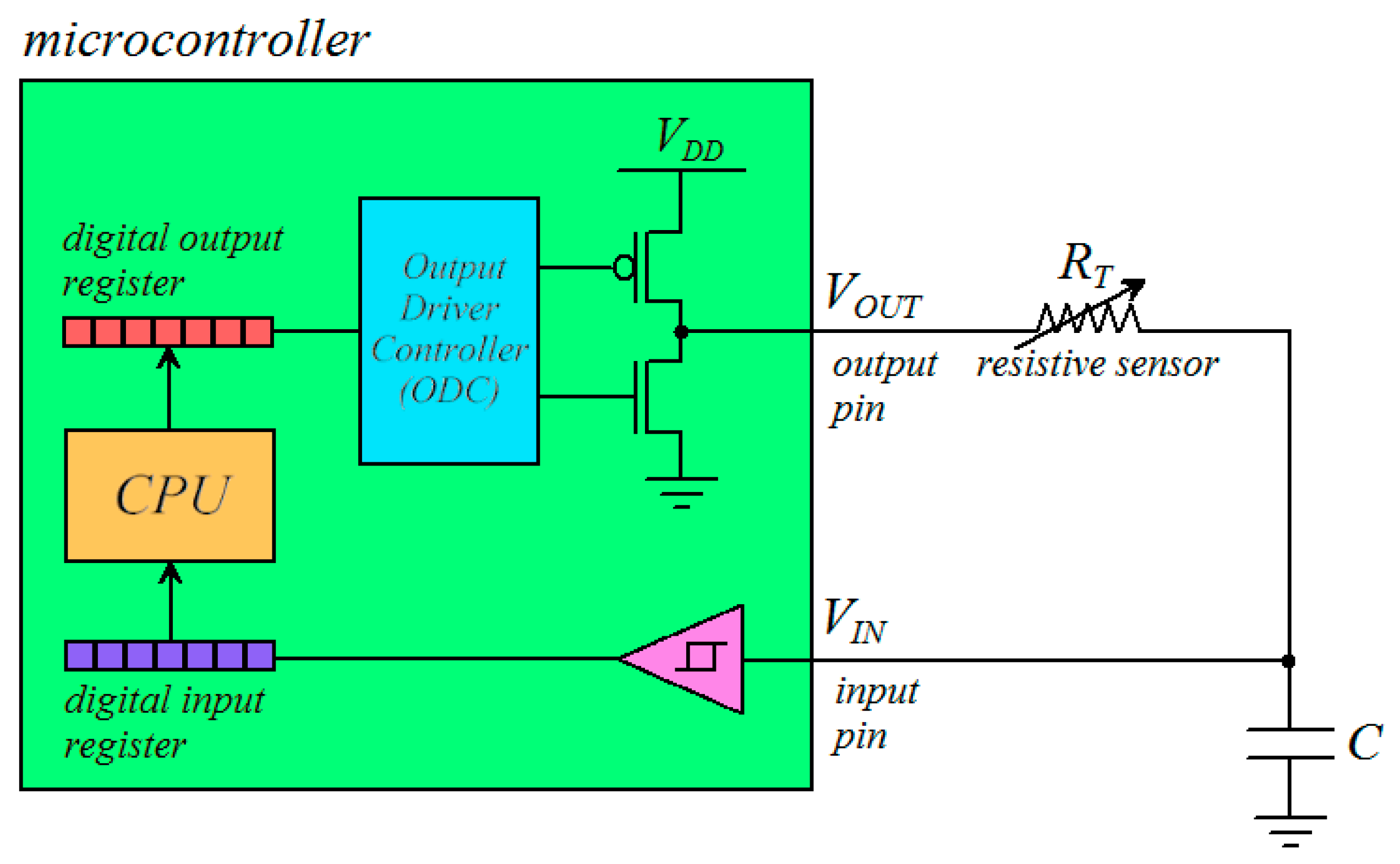

2.1. SMDI-Based Measurements

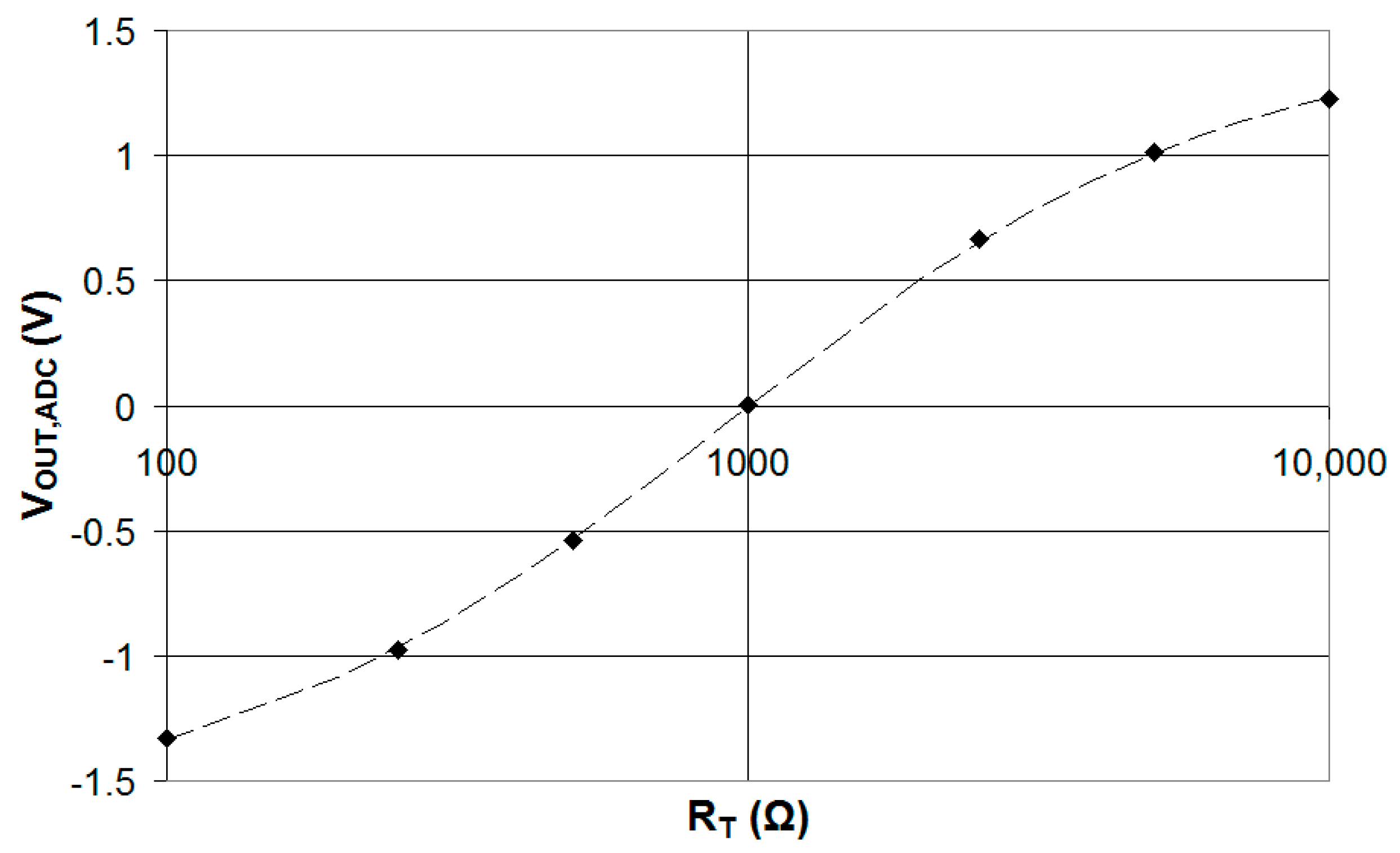

2.2. ADC-Based Measurements

3. Simulation Results

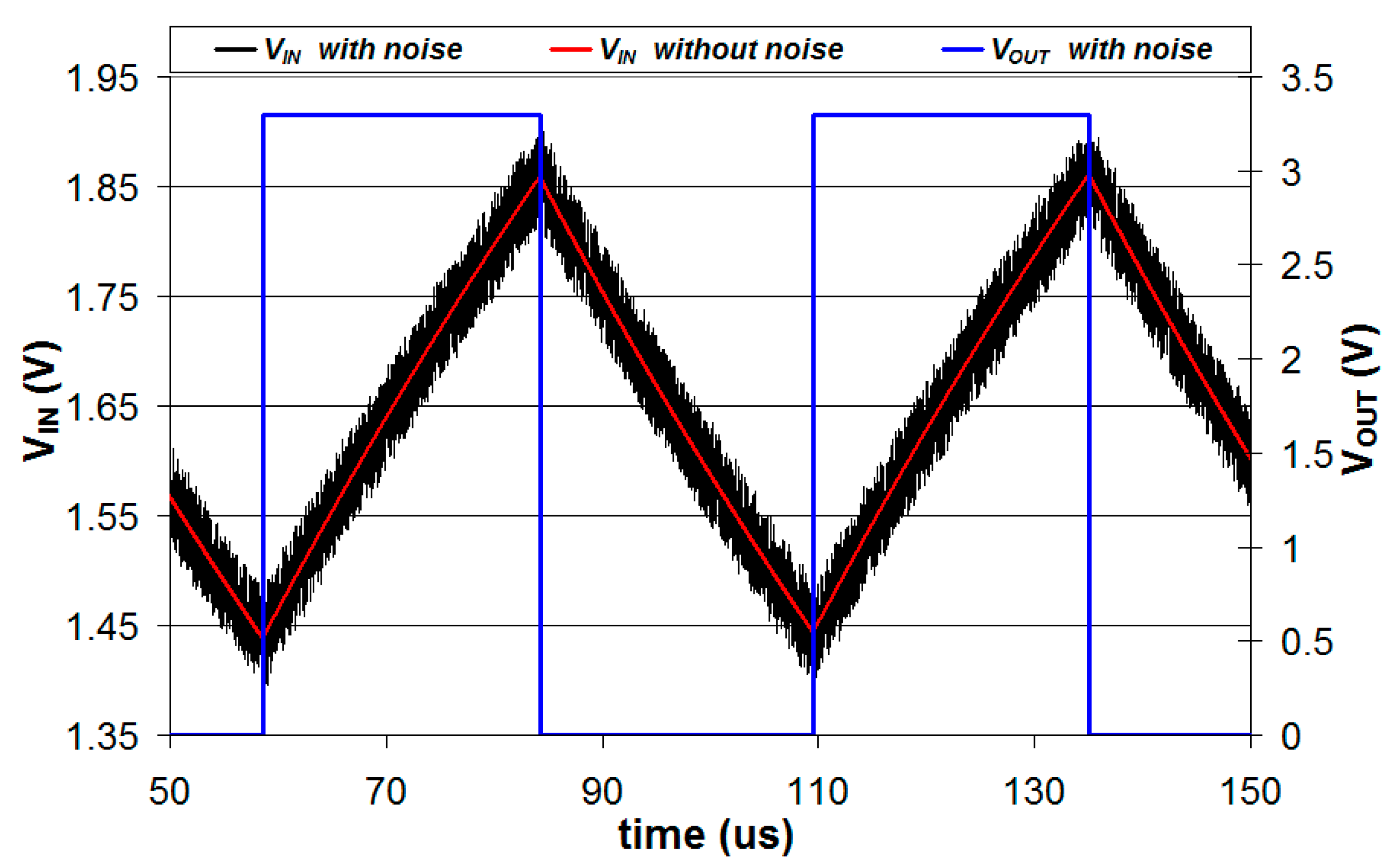

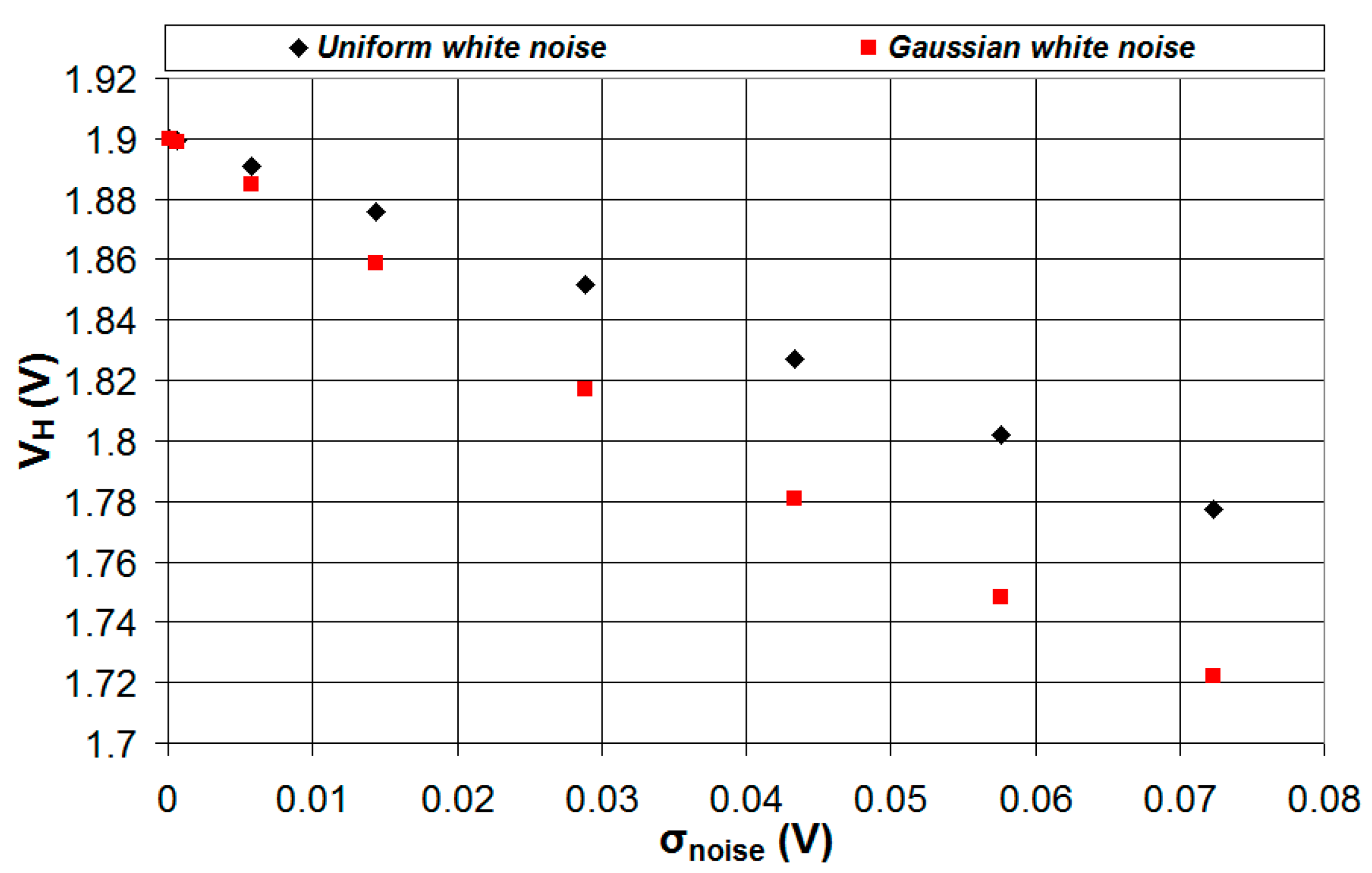

3.1. SMDI-Based Measurements

3.2. ADC-Based Measurements

4. Discussion

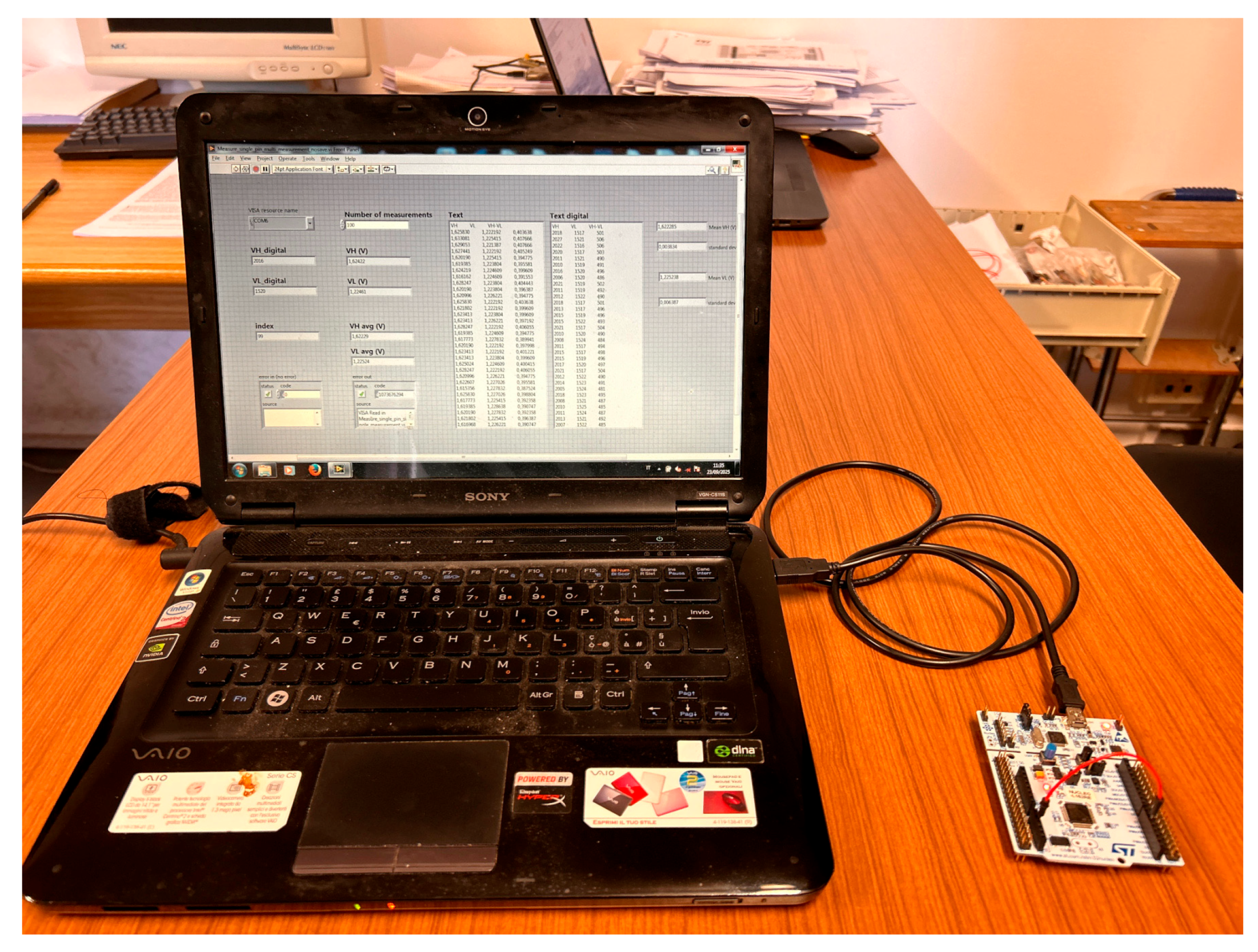

5. Experimental Measurements on a Microcontroller

- The output of the microcontroller DAC is shorted with the input pin to be tested using a cable. Cables of three different lengths (11.5 cm, 26.5 cm, and 102.5 cm) were tested, since the longer the cable, the higher the probability that electromagnetic interference degrades the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Meanwhile, the microcontroller generates an analog voltage at the DAC output that increases from 0 V to 3.3 V, with steps of 12.89 mV. After the DAC output voltage is increased to a new value, the microcontroller waits 2 ms to allow the voltage stabilization, and then reads the value of the digital input pin. The Schmitt trigger threshold VH is estimated as the DAC output voltage for which the input pin logic value switches from 0 to 1.

- Then, the microcontroller generates an analog voltage at the DAC output that decreases from 3.3 V to 0 V, with steps of 12.89 mV. Again, after the DAC output voltage is decreased to a new value, the microcontroller waits 2 ms to allow the voltage stabilization, and then reads the value of the digital input pin. The Schmitt trigger threshold VL is estimated as the DAC output voltage for which the input pin logic value switches from 1 to 0.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dhall, S.; Mehta, B.R.; Tyagi, A.K.; Sood, K. A review on environmental gas sensors: Materials and technologies. Sens. Int. 2021, 2, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Mei, H.; Liu, D.; Zeng, N.; Tang, X.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y. Calibrations of low-cost air pollution monitoring sensors for CO, NO2, O3, and SO2. Sensors 2021, 21, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilaș, S.; Ursachi, C.Ș.; Perța-Crișan, S.; Munteanu, F.D. Recent trends in biosensors for environmental quality monitoring. Sensors 2022, 22, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L. Calibrating low-cost sensors for ambient air monitoring: Techniques, trends, and challenges. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M.; Valli, E.; Bendini, A.; Gallina Toschi, T.; Riccò, B. A Portable Battery-Operated Sensor System for Simple and Rapid Assessment of Virgin Olive Oil Quality Grade. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M.; Bendini, A.; Valli, E.; Gallina Toschi, T. Field-deployable determinations of peroxide index and total phenolic content in olive oil using a promising portable sensor system. Sensors 2023, 23, 5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrabi, H.; Sani, P.S.; Orooji, Y.; Majidi, M.R.; Yoon, Y.; Khataee, A. MOF-based sensor platforms for rapid detection of pesticides to maintain food quality and safety. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 165, 113176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Hu, Z.; Hu, X.; Li, D.; Tian, S. Electronic tongue and electronic nose for food quality and safety. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodero, A.; Escher, A.; Bertucci, S.; Castellano, M.; Lova, P. Intelligent packaging for real-time monitoring of food-quality: Current and future developments. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M.; Valli, E.; Glicerina, V.T.; Rocculi, P.; Gallina Toschi, T.; Riccò, B. Optical determination of solid fat content in fats and oils: Effects of wavelength on estimated accuracy. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 2100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaartinen, E.; Dunphy, K.; Sadhu, A. LiDAR-based structural health monitoring: Applications in civil infrastructure systems. Sensors 2022, 22, 4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, M.; Lourenço, P.B.; Ramana, G.V. Structural health monitoring of civil engineering structures by using the internet of things: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 48, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickrema, U.M.N.; Herath, H.M.C.M.; Hettiarachchi, N.K.; Sooriyaarachchi, H.P.; Epaarachchi, J.A. Fibre-optic sensor and deep learning-based structural health monitoring systems for civil structures: A review. Measurement 2022, 199, 111543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Bournas, D. Structural health monitoring and management of cultural heritage structures: A state-of-the-art review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M.; Parolin, C.; Vitali, B.; Riccò, B. Computer vision approach for the determination of microbial concentration and growth kinetics using a low cost sensor system. Sensors 2019, 19, 5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M.; Parolin, C.; Vitali, B.; Riccò, B. A portable sensor system for bacterial concentration monitoring in metalworking fluids. J. Sens. Sens. Syst. 2018, 7, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canciu, A.; Tertis, M.; Hosu, O.; Cernat, A.; Cristea, C.; Graur, F. Modern analytical techniques for detection of bacteria in surface and wastewaters. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, S.; De La Franier, B.; Davoudian, K.; Hianik, T.; Thompson, M. Detection of E. coli bacteria in milk by an acoustic wave aptasensor with an anti-fouling coating. Sensors 2022, 22, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnachi, R.C.; Sui, N.; Ke, B.; Luo, Z.; Bhalla, N.; He, D.; Yang, Z. Biosensors for rapid detection of bacterial pathogens in water, food and environment. Environ. Int. 2022, 166, 107357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoun, O.; Khriji, S.; Naifar, S.; Bradai, S.; Bouattour, G.; Bouhamed, A.; El Houssaini, D.; Viehweger, C. Prospects of wireless energy-aware sensors for smart factories in the industry 4.0 era. Electronics 2021, 10, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, A.; Garg, N.; Nagla, K.S.; Nair, T.S.; Jaiswal, S.K.; Yadav, S.; Aswal, D.K. Challenges in sensors technology for industry 4.0 for futuristic metrological applications. Mapan 2021, 36, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M.; Habib, S.; Javed, A.R.; Rizwan, M.; Srivastava, G.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Lin, J.C.W. Applications of wireless sensor networks and internet of things frameworks in the industry revolution 4.0: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Internet of things for smart factories in industry 4.0, a review. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2023, 3, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, K.; Boddu, R.S.K.; Kapila, D.; Bangare, S.L.; Chandnani, N.; Saravanan, G. A review paper on wireless sensor network techniques in Internet of Things (IoT). Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 51, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic, J.A. Wireless sensor networks. Computer 2008, 41, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, N.; Abid, M.R.; Benhaddou, D.; Gerndt, M. Wireless sensors networks for Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Ninth International Conference on Intelligent Sensors, Sensor Networks and Information Processing (ISSNIP), Singapore, 21–24 April 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kandris, D.; Nakas, C.; Vomvas, D.; Koulouras, G. Applications of wireless sensor networks: An up-to-date survey. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2020, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; He, T.; Zhang, Y.; Temes, G.C. Incremental analog-to-digital converters for high-resolution energy-efficient sensor interfaces. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2015, 5, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasilenko, V.G.; Nikolskyy, A.I.; Lazarev, A.A. Multichannel serial-parallel analog-to-digital converters based on current mirrors for multi-sensor systems. Opt. Syst. Des. 2012, 8550, 598–609. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, D. Adaptive low-power analog/digital converters for wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Intelligent Solutions in Embedded Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 20 May 2005; pp. 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.S.; Kuo, S.C.; Chen, C.H. A multistep multistage fifth-order incremental delta sigma analog-to-digital converter for sensor interfaces. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2023, 58, 2733–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kaur, R.; Singh, D. Energy harvesting in wireless sensor networks: A taxonomic survey. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 118–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Han, Y.; Yao, M.; Song, X. Trust based secure and energy efficient routing protocol for wireless sensor networks. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 10585–10596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, P.; Stephan, T.; Shankar, A.; Liu, P. FAJIT: A fuzzy-based data aggregation technique for energy efficiency in wireless sensor network. Complex Intell. Syst. 2021, 7, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverter, F. The art of directly interfacing sensors to microcontrollers. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2012, 2, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverter, F. Power consumption in direct interface circuits. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2012, 62, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverter, F. A microcontroller-based interface circuit for three-wire connected resistive sensors. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 2006704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverter, F. A direct approach for interfacing four-wire resistive sensors to microcontrollers. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 34, 037001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M.; Omaña, M. Accuracy of NTC Thermistor Measurements Using the Sensor to Microcontroller Direct Interface. Eng. Proc. 2024, 82, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Grossi, M.; Omaña, M.; Metra, C. Impact of aging on temperature measurements performed using a resistive temperature sensor with sensor-to-microcontroller direct interface. Microelectron. Reliab. 2025, 169, 115729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, Z. A measurement method for lossy capacitive relative humidity sensors based on a direct sensor-to-microcontroller interface circuit. Measurement 2021, 170, 108702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, Z. A measurement method for capacitive sensors based on a versatile direct sensor-to-microcontroller interface circuit. Measurement 2020, 155, 107547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverter, F.; Casas, Ò. Interfacing differential capacitive sensors to microcontrollers: A direct approach. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2009, 59, 2763–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitán-Pitre, J.E.; Gasulla, M.; Pallas-Areny, R. Analysis of a direct interface circuit for capacitive sensors. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2009, 58, 2931–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokolanski, Z.; Jordana, J.; Gasulla, M.; Dimcev, V.; Reverter, F. Direct inductive sensor-to-microcontroller interface circuit. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2015, 224, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokolanski, Z.; Jordana, J.; Gasulla, M.; Dimcev, V.; Reverter, F. Microcontroller-based interface circuit for inductive sensors. Procedia Eng. 2014, 87, 1251–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Asif, A.; Ali, A.; Abdin, M.Z.U. Resolution enhancement in directly interfaced system for inductive sensors. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2018, 68, 4104–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M. Efficient and Accurate Analog Voltage Measurement Using a Direct Sensor-to-Digital Port Interface for Microcontrollers and Field-Programmable Gate Arrays. Sensors 2024, 24, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.K. Electrical noise as a reliability indicator in electronic devices and components. IEE Proc.-Circuits Devices Syst. 2002, 149, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, A. Analysis and Simulation of Noise in Nonlinear Electronic Circuits and Systems; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 425. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilescu, G. Electronic Noise and Interfering Signals: Principles and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- LTSpice Circuit Simulator. Available online: https://www.analog.com/en/resources/design-tools-and-calculators/ltspice-simulator.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- LTC2311-12 ADC. Available online: https://www.analog.com/en/products/ltc2311-12.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

| RT (Ω) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 250 | 500 | 1000 | 2500 | 5000 | 10,000 | ||||||||

| Vnoise,PP (mV) | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ |

| 1.25 | 101.00 | 0.08 | 251.04 | 0.21 | 500.89 | 0.35 | 1000.5 | 0.64 | 2498.4 | 1.04 | 4993.6 | 1.66 | 9984.5 | 3.65 |

| 2.5 | 100.99 | 0.16 | 250.88 | 0.38 | 500.49 | 0.56 | 999.01 | 1.03 | 2494.2 | 1.78 | 4985.6 | 3.39 | 9965.6 | 5.31 |

| 5 | 100.91 | 0.27 | 250.68 | 0.61 | 498.84 | 0.87 | 996.33 | 1.70 | 2484.4 | 3.10 | 4963.8 | 4.47 | 9925.4 | 7.05 |

| 10 | 100.68 | 0.49 | 249.12 | 0.93 | 496.43 | 1.48 | 989.59 | 2.72 | 2465.9 | 4.39 | 4919.6 | 7.79 | 9835.8 | 12.9 |

| 20 | 99.41 | 0.73 | 246.09 | 1.54 | 488.47 | 2.01 | 971.34 | 3.28 | 2417.0 | 7.08 | 4840.7 | 10.8 | 9644.9 | 19.6 |

| 33.3 | 97.95 | 0.89 | 242.02 | 2.33 | 476.36 | 2.38 | 950.23 | 6.57 | 2366.3 | 11.9 | 4723.0 | 20.0 | 9416.5 | 32.7 |

| 40 | 97.18 | 1.18 | 237.50 | 2.14 | 472.03 | 3.92 | 941.65 | 5.42 | 2331.8 | 13.3 | 4661.1 | 18.4 | 9302.2 | 24.9 |

| 50 | 95.99 | 1.70 | 234.42 | 3.09 | 464.78 | 4.35 | 925.23 | 7.40 | 2286.8 | 16.4 | 4546.8 | 18.5 | 9100.2 | 34.1 |

| 100 | 88.49 | 2.67 | 214.40 | 4.68 | 424.73 | 6.46 | 841.96 | 8.53 | 2064.6 | 29.0 | 4062.7 | 19.5 | 8154.9 | 46.5 |

| RT (Ω) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 250 | 500 | 1000 | 2500 | 5000 | 10,000 | ||||||||

| Vnoise,PP (mV) | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ |

| 1.25 | 102.48 | 0.16 | 247.91 | 0.10 | 495.26 | 0.19 | 1003.0 | 0.64 | 2534.9 | 1.82 | 5025.3 | 4.41 | 9739.9 | 20.2 |

| 2.5 | 102.45 | 0.22 | 247.86 | 0.28 | 495.32 | 0.35 | 1003.0 | 0.64 | 2535.3 | 1.96 | 5027.2 | 5.94 | 9742.2 | 27.8 |

| 5 | 102.43 | 0.41 | 247.84 | 0.47 | 495.31 | 0.61 | 1003.0 | 1.02 | 2535.5 | 3.07 | 5027.2 | 9.16 | 9741.3 | 34.3 |

| 10 | 102.40 | 0.83 | 247.79 | 0.91 | 495.23 | 1.19 | 1002.9 | 1.91 | 2535.3 | 5.55 | 5026.7 | 16.0 | 9740.2 | 52.5 |

| 20 | 102.31 | 1.62 | 247.70 | 1.82 | 495.18 | 2.31 | 1002.8 | 3.83 | 2534.8 | 10.9 | 5026.2 | 30.8 | 9737.0 | 98.6 |

| 33.3 | 102.16 | 2.76 | 247.55 | 3.06 | 495.05 | 3.84 | 1002.7 | 6.32 | 2534.5 | 17.9 | 5025.7 | 50.8 | 9737.0 | 159 |

| 40 | 102.10 | 3.31 | 247.52 | 3.70 | 495.01 | 4.62 | 1002.5 | 7.59 | 2534.3 | 21.4 | 5025.5 | 60.4 | 9734.5 | 190 |

| 50 | 102.01 | 4.14 | 247.44 | 4.63 | 494.89 | 5.79 | 1002.5 | 9.42 | 2534.1 | 26.4 | 5024.8 | 74.9 | 9732.8 | 236 |

| 100 | 101.61 | 8.28 | 247.03 | 9.23 | 494.55 | 11.6 | 1002.1 | 18.9 | 2533.3 | 53.5 | 5022.5 | 152 | 9740.8 | 470 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grossi, M.; Omaña, M. Impact of Electrical Noise on the Accuracy of Resistive Sensor Measurements Using Sensor-to-Microcontroller Direct Interface. Eng. Proc. 2025, 118, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26551

Grossi M, Omaña M. Impact of Electrical Noise on the Accuracy of Resistive Sensor Measurements Using Sensor-to-Microcontroller Direct Interface. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 118(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26551

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrossi, Marco, and Martin Omaña. 2025. "Impact of Electrical Noise on the Accuracy of Resistive Sensor Measurements Using Sensor-to-Microcontroller Direct Interface" Engineering Proceedings 118, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26551

APA StyleGrossi, M., & Omaña, M. (2025). Impact of Electrical Noise on the Accuracy of Resistive Sensor Measurements Using Sensor-to-Microcontroller Direct Interface. Engineering Proceedings, 118(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26551