Computational Studies of Thiosemicarbazone-Based Metal Complexes and Their Biological Applications †

Abstract

1. Introduction

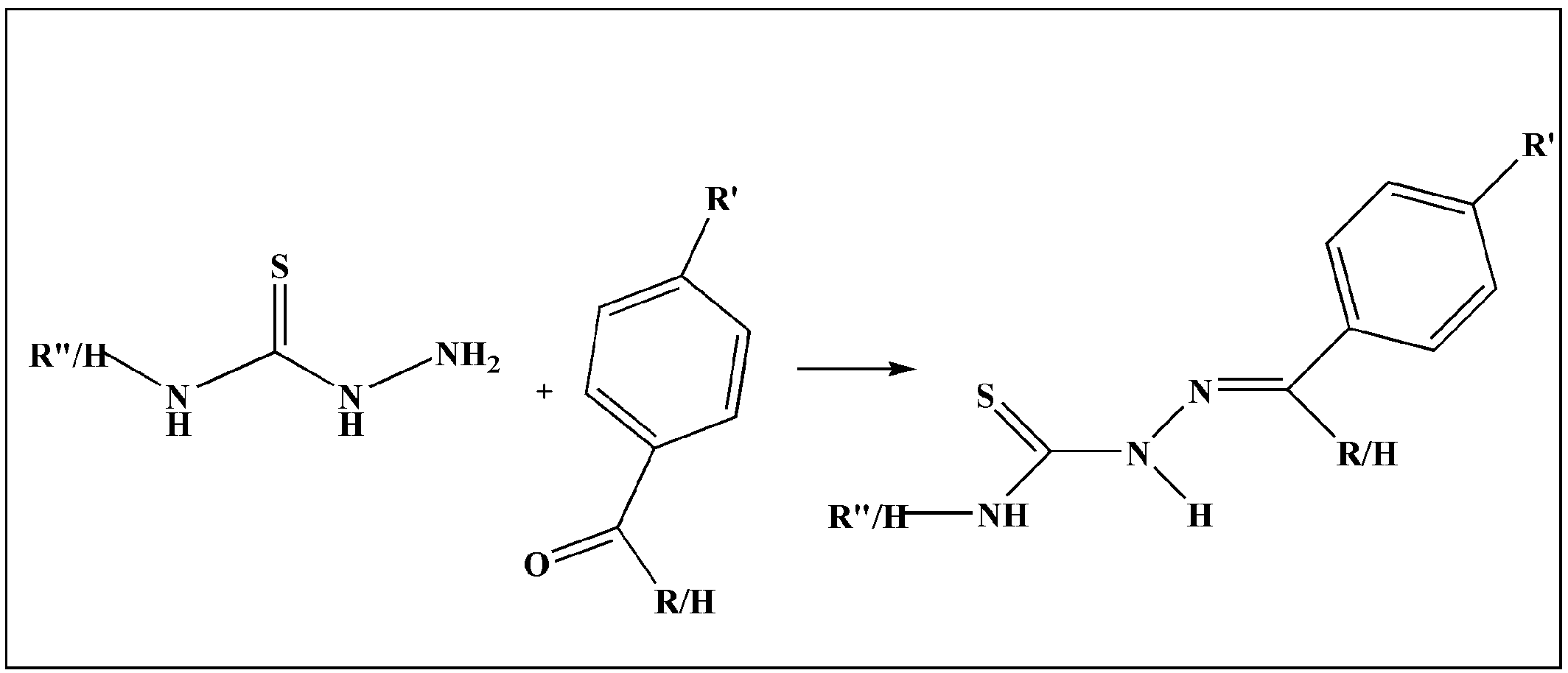

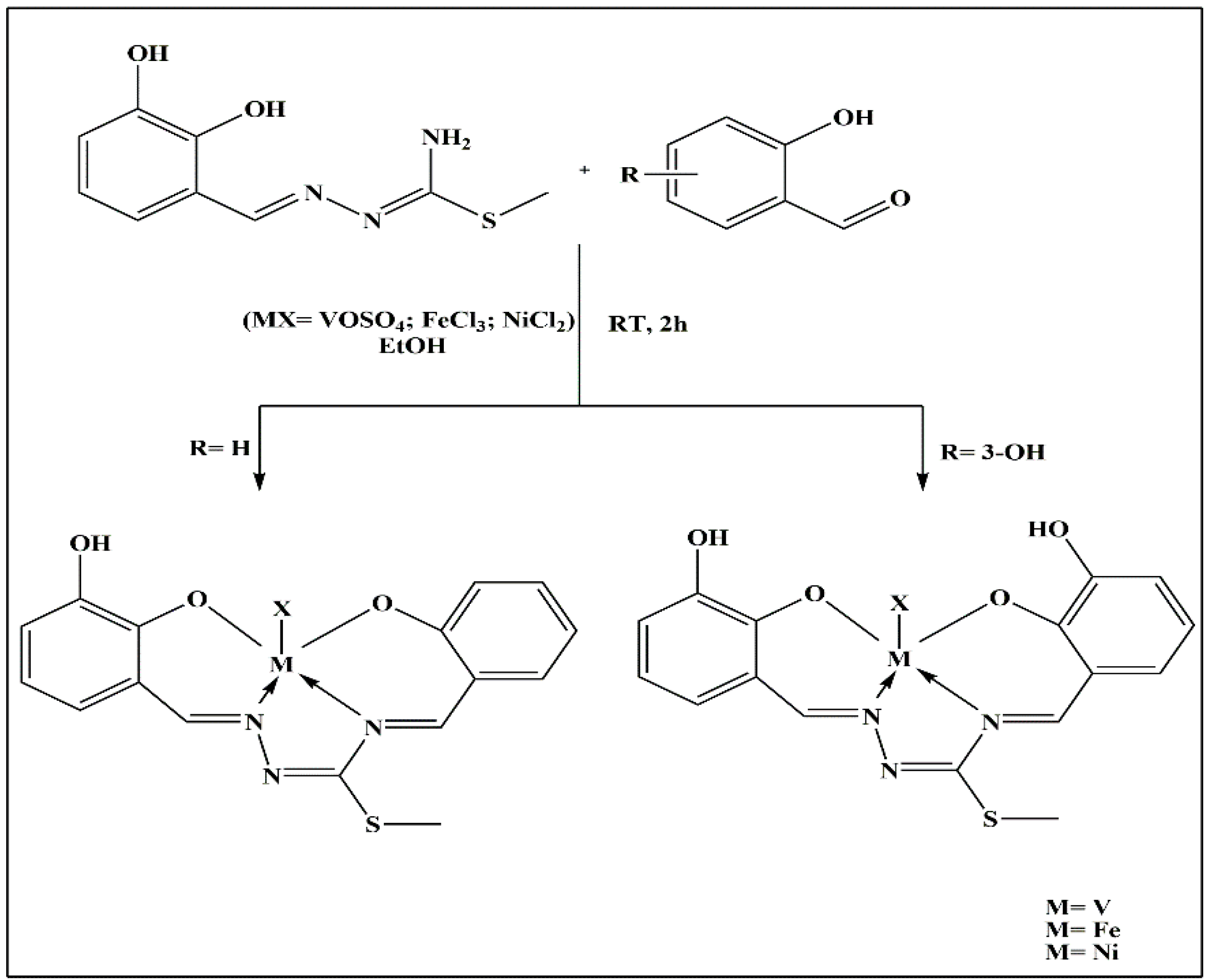

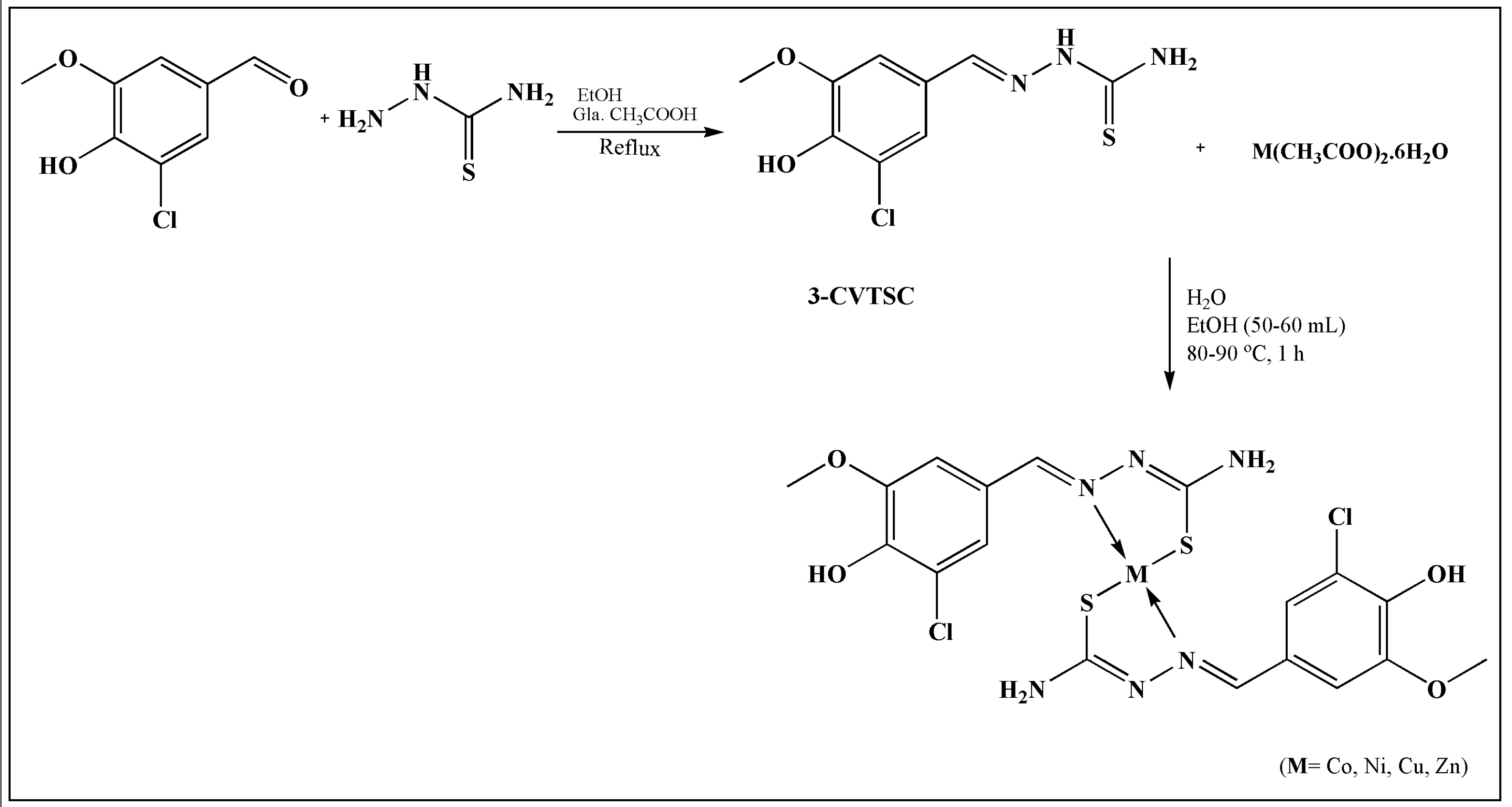

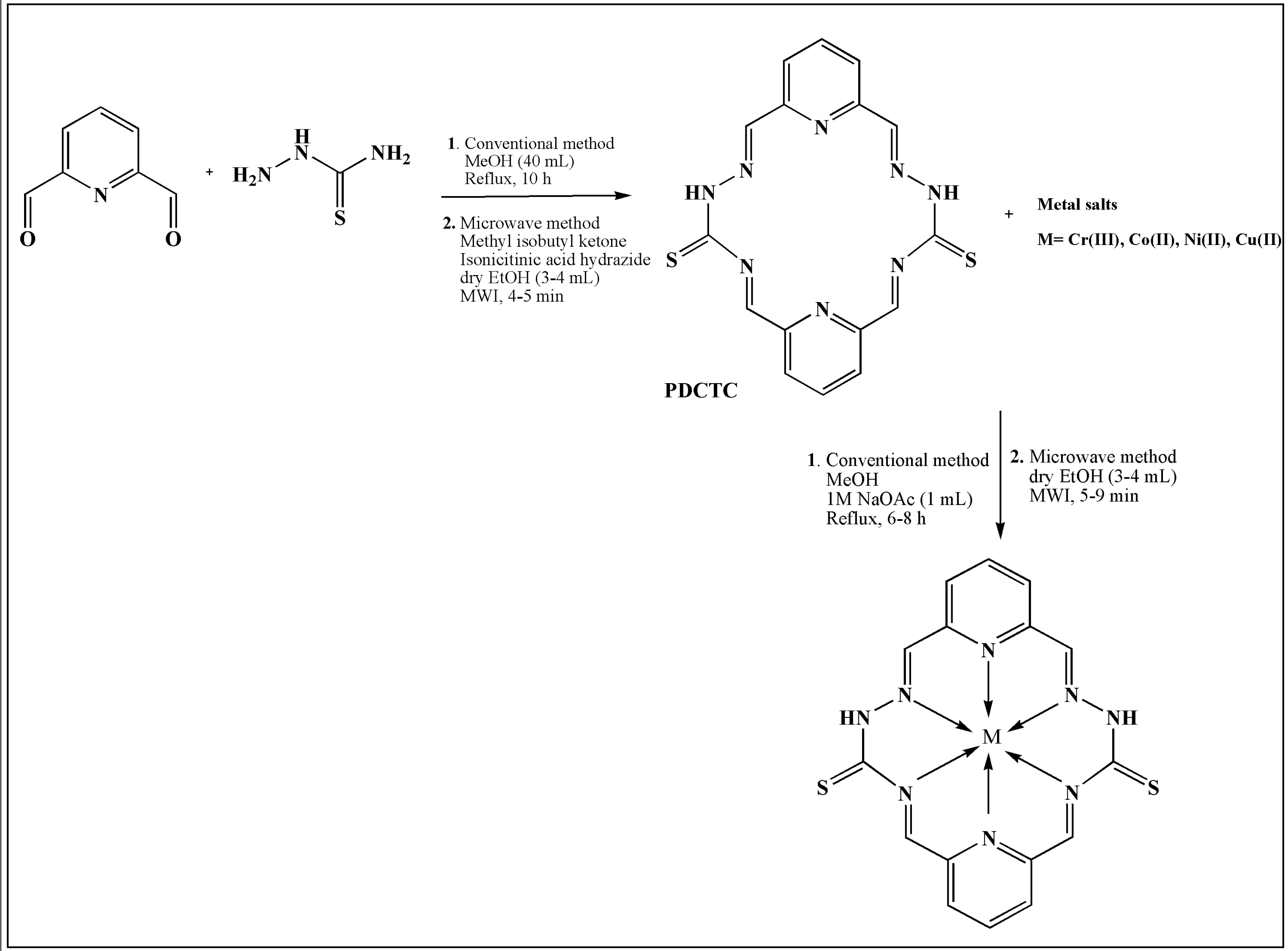

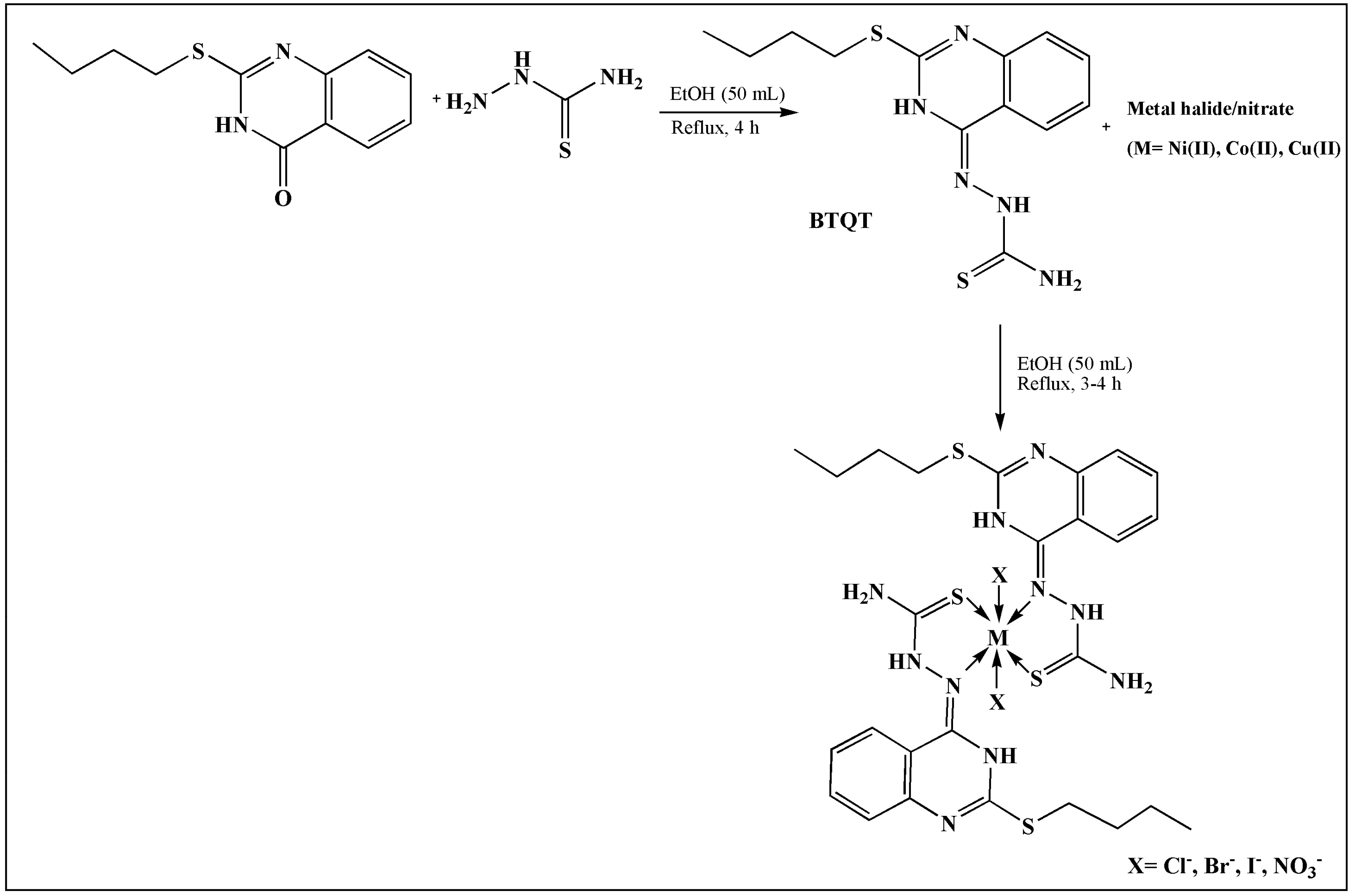

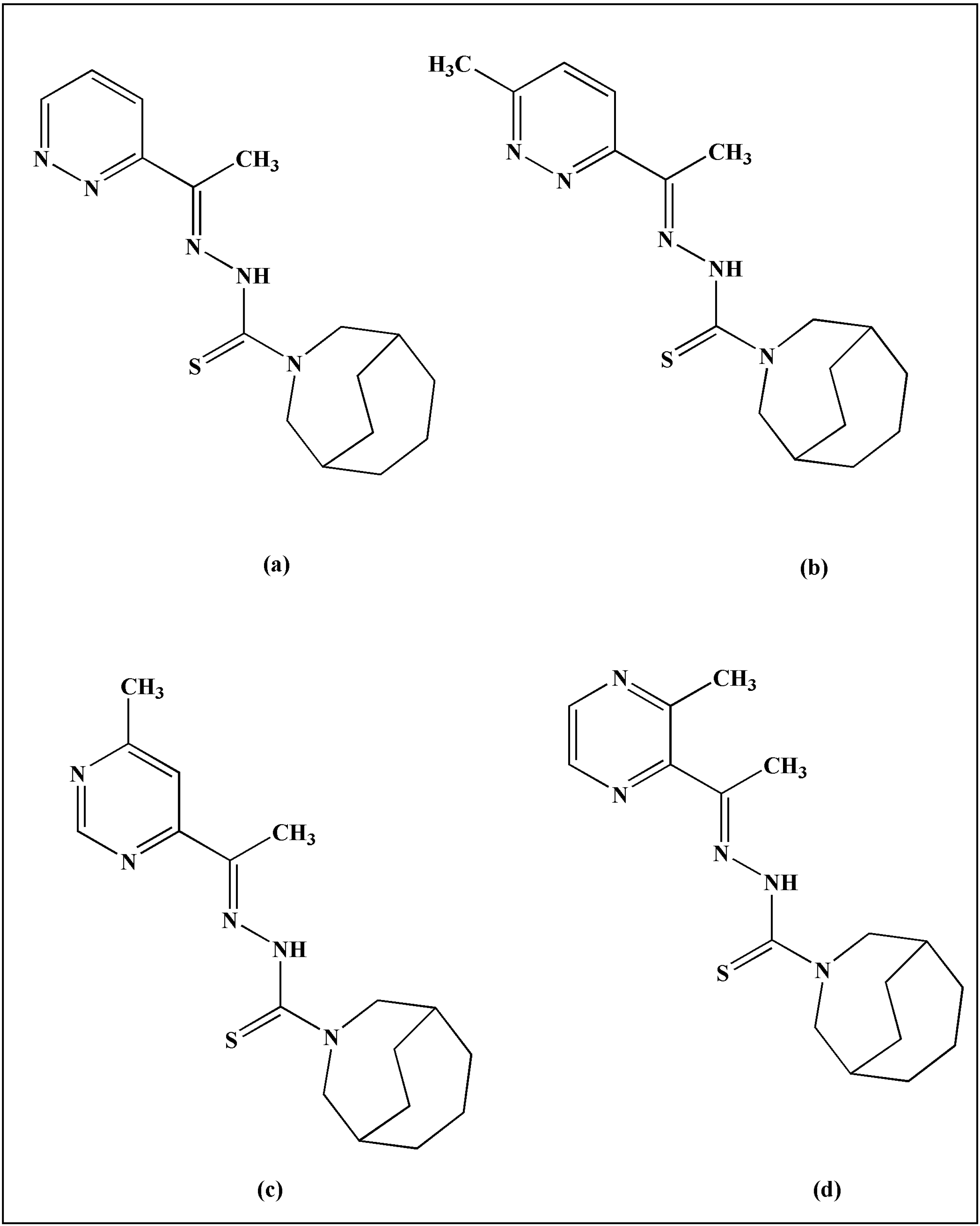

2. TSCs and Their Metal Complexes

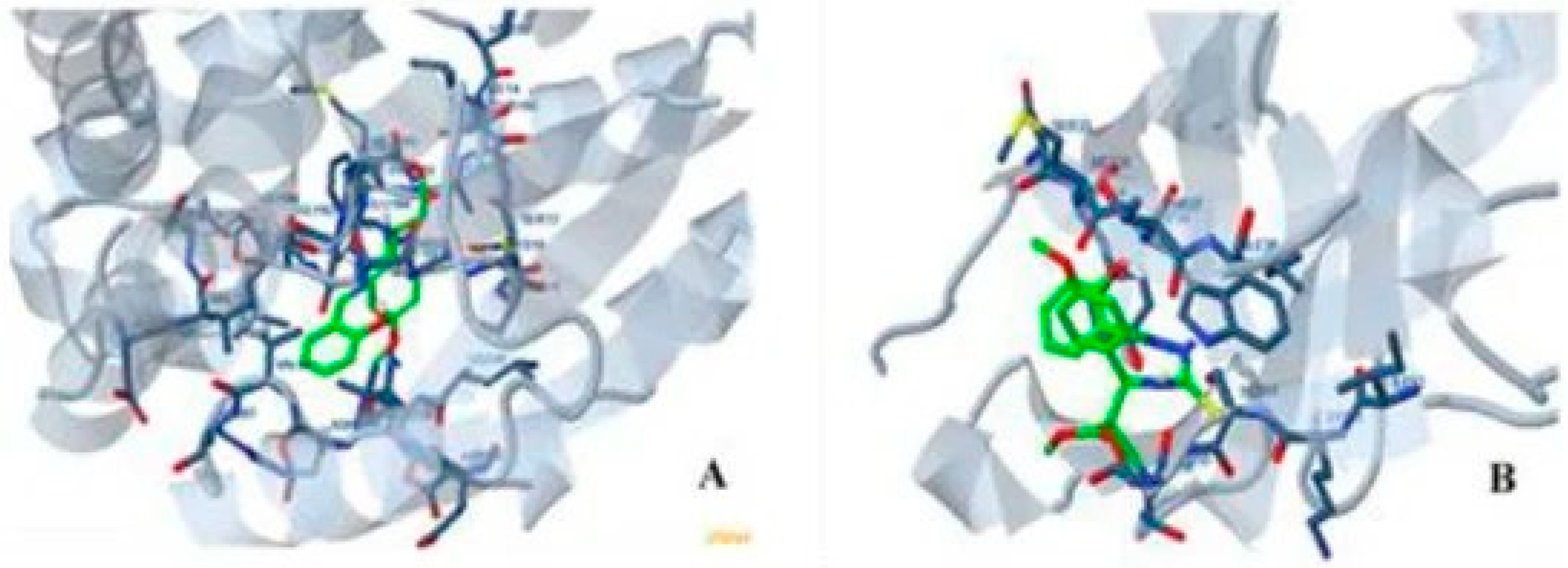

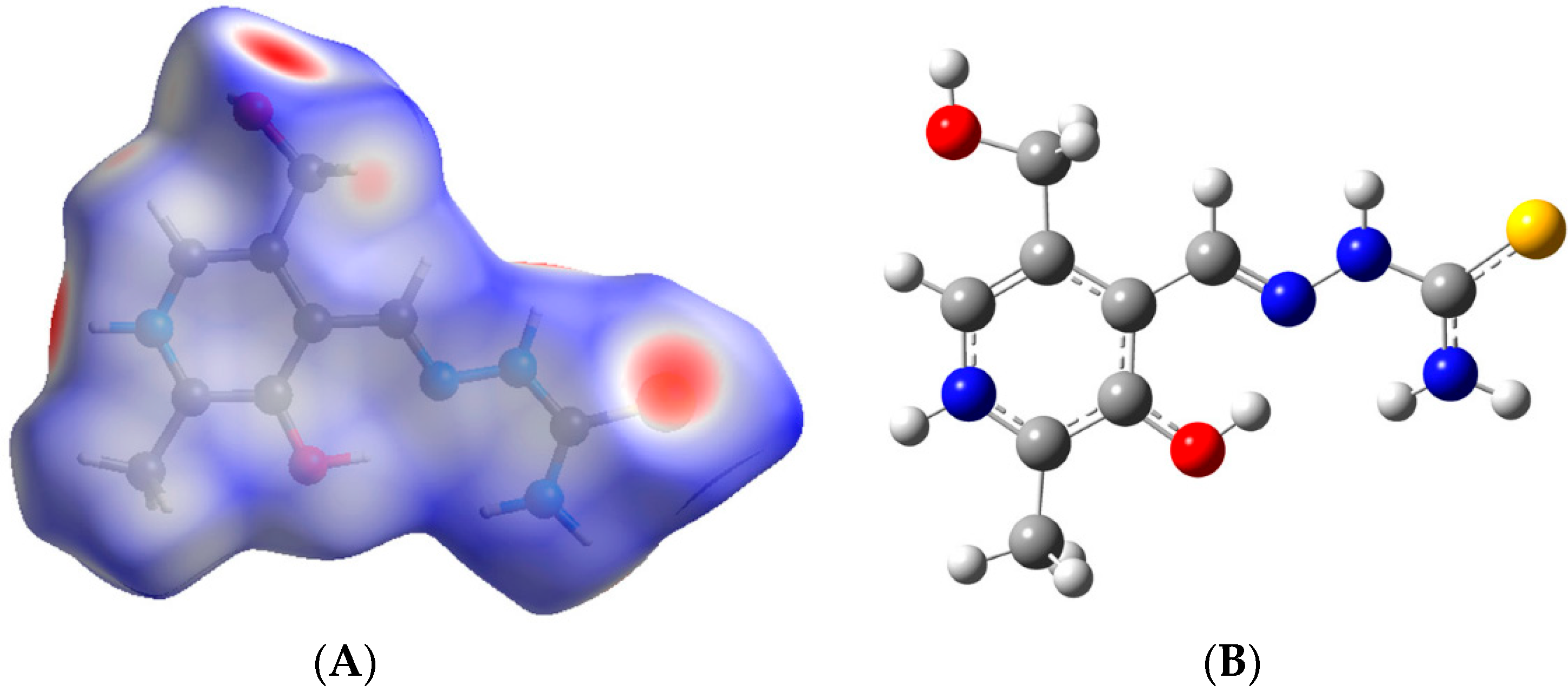

3. Computational Studies

4. Mechanistic Insight of TSCs

4.1. Inhibition of DNA Interactions and Topo II

4.2. ROS Generation

4.3. Multidrug Resistance Protein (MDR1) Inhibition

5. Future Prospects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, T.; Raza, S.; Hashmi, K.; Ahmad, M.I.; Khan, A.R. Structural modifications for biological activity enhancements in thiosemicarbazone scaffolds and their metal complexes. Synlett 2025, 36, 2732–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Ahmad, R.; Joshi, S.; Khan, A.R. Anticancer potential of metal thiosemicarbazone complexes: A review. Chem. Sin. 2015, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef, T.A.; El-Reash, G.A. Synthesis, and biological evaluation of complexes based on thiosemicarbazone ligand. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1201, 127180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netalkar, P.P.; Netalkar, S.P.; Revankar, V.K. Transition metal complexes of thiosemicarbazone: Synthesis, structures and invitro antimicrobial studies. Polyhedron 2015, 100, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, S.E.; Iqbal, A.; Rahman, K.A.; Tahmeena, K. Thiosemicarbazone Complexes as Versatile Medicinal Chemistry Agents: A Review. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2019, 9, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, K.; Rai, S.; Sharma, S.; Gupta, S.; Mishra, P.; Veg, E.; Khan, T.; Gupta, A.; Joshi, S. Spectroscopic and Quantum Chemical Studies of some Novel Mixed-ligand complexes of Vanadium and Comparative Evaluation of their Antimicrobial and Antioxidant activities. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 174, 113967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoufal, F.; Guesmi, S.; Jouffret, L.; Ketatni, E.M.; Sergent, N.; Obbade, S.; Bentiss, F. Novel copper(II) and nickel(II) coordination complexes of 2,4-pentanedione bis-thiosemicarbazone: Synthesis, structural characterization, computational studies, and magnetic properties. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 141, 109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, M.; Antil, N.; Kumar, B.; Devi, J.; Garg, S. Exploring the novel aryltellurium(IV) complexes: Synthesis, characterization, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antimalarial, theoretical and ADMET studies. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 159, 111743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roney, M.; Dubey, A.; Hassan Nasir, M.; Tufail, A.; Tajuddin, S.N.; Mohd Aluwi, M.F.F.; Huq, A.M. Computational evaluation of quinones of Nigella sativa L. as potential inhibitor of dengue virus NS5 methyltransferase. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 1, 8701–8711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, I.; Khan, T.; Maurya, A.K.; Irfan Azad, M.; Mishra, N.; Alanazi, A.M. Identification of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 inhibitors through in silico structure-based virtual screening and molecular interaction studies. J. Mol. Recognit. 2021, 34, e2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal-Demirci, T.; Şahin, M.; Kondakçı, E.; Özyürek, M.; Ülküseven, B.; Apak, R. Synthesis and antioxidant activities of transition metal complexes based 3-hydroxysalicylaldehyde-S-methylthiosemicarbazone. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 138, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahetar, J.G.; Mamtora, M.J.; Gondaliya, M.B.; Manawar, R.B.; Shah, M.K. Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of transition metal complexes of thiosemicarbazone bearing vanillin moiety. World J. Pharm. Res. 2014, 3, 4383–4392. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.F.A.; Mahammadyunus, V. Microwave synthesis and antimicrobial activity of some Copper (II), Cobalt (II), Nickel (II) and Chromium (III) complexes with Schiff base 2, 6-pyridinedicarboxaldehyde-Thiosemicarbazone. Orient. J. Chem. 2014, 30, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, B.K.; Sinha, P.; Singh, V.; Vidhyarthi, S.N.; Pandey, A. Structural and Spectroscopic Aspects of Schiff Base Metal Complexes of Cobalt (II), Nickel (II) and Copper (II). Orient. J. Chem. 2014, 30, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.J.; Bell, N.L.; Stevens, C.J.; Zhong, Y.X.; Schreckenbach, G.; Arnold, P.L.; Love, J.B.; Pan, Q.J. Relativistic DFT and experimental studies of mono-and bis-actinyl complexes of an expanded Schiff-base polypyrrole macrocycle. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 15910–15921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeglis, B.M.; Divilov, V.; Lewis, J.S. Role of metalation in the topoisomerase IIα inhibition and antiproliferation activity of a series of α-heterocyclic-N4-substituted thiosemicarbazones and their Cu (II) complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 2391–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matesanz, A.I.; Albacete, P.; Souza, P. Synthesis and characterization of a new bioactive mono (thiosemicarbazone) ligand based on 3, 5-diacetyl-1, 2, 4-triazol diketone and its palladium and platinum complexes. Polyhedron 2016, 109, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasi, E.; Atalay, E.B.; Erdogan, D.; Sen, B.; Pakyapan, B.; Kayali, H.A. Synthesis and characterization of thiosemicarbazone-functionalized organoruthenium (II)-arene complexes: Investigation of antitumor characteristics in colorectal cancer cell lines. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 106, 110152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarapu, L.N.; Baek, S.O. Synthesis and characterization of 4-benzyloxybenzaldehyde-4-methyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (containing Sulphur and nitrogen donor atoms) and its Cd (II) complex. Metals 2015, 5, 2266–2276. [Google Scholar]

- Gaber, A.; Refat, M.S.; Belal, A.A.; El-Deen, I.M.; Hassan, N.; Zakaria, R.; Alhomrani, M.; Alamri, A.S.; Alsanie, W.F.; Saied, E.M. New mononuclear and binuclear Cu (II), Co (II), Ni (II), and Zn (II) thiosemicarbazone complexes with potential biological activity: Antimicrobial and molecular docking study. Molecules 2021, 26, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guin, M.; Sarkar, P.; Khanna, S.; Arora, S.; Boora, A.; Munjal, P. Elucidating anti-Alzheimer role of 4-anisaldehyde thiosemicarbazone and its zinc and cadmium complexes: DFT calculation and molecular docking studies. Vietnam J. Chem. 2025, 46, 1119–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manakkadan, V.; Haribabu, J.; Valsan, A.K.; Palakkeezhillam, V.N.V.; Rasin, P.; Moraga, D.; Kumar, V.S.; Muena, J.P.; Sreekanth, A. Synthesis and characterization of copper (II) complex derived from newly synthesized acenaphthene quinone thiosemicarbazone ligands: Computational studies, in vitro binding with DNA/BSA and anticancer studies. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2025, 574, 122369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.A.; Costa, W.R.; Faria, E.D.F.; Bessa, M.A.D.S.; Menezes, R.D.; Martins, C.H.; Maia, P.I.; Deflon, V.M.; Oliveira, C.G. Copper (II) complexes based on thiosemicarbazone ligand: Preparation, crystal structure, Hirshfeld surface, energy framework, antiMycobacterium activity, in silico and molecular docking studies. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2021, 223, 111543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Azad, I.; Ahmad, R.; Raza, S.; Dixit, S.; Joshi, S.; Khan, A.R. Synthesis, characterization, computational studies and biological activity evaluation of Cu, Fe, Co and Zn complexes with 2-butanone thiosemicarbazone and 1, 10-phenanthroline ligands as anticancer and antibacterial agents. Excli J. 2018, 17, 331. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed, D.S.; Hassan, S.S.; Jassim, L.S.; Issa, A.A.; Al-Oqaili, F.; Albayaty, M.K.; Hasoon, B.A.; Jabir, M.S.; Rasool, K.H.; Elbadawy, H.A. Structural and topological analysis of thiosemicarbazone-based metal complexes: Computational and experimental study of bacterial biofilm inhibition and antioxidant activity. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jevtovic, V.; Alshamari, A.K.; Milenković, D.; Dimitrić Marković, J.; Marković, Z.; Dimić, D. The effect of metal ions (Fe, Co, Ni, and Cu) on the molecular-structural, protein binding, and cytotoxic properties of metal pyridoxal-thiosemicarbazone complexes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.K.; Skladanowski, A.; Bojanowski, K. The roles of DNA topoisomerase II during the cell cycle. Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 1996, 2, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Easmon, J.; Pürstinger, G.; Heinisch, G.; Roth, T.; Fiebig, H.H.; Holzer, W.; Jäger, W.; Jenny, M.; Hofmann, J. Synthesis, cytotoxicity, and antitumor activity of copper (II) and iron (II) complexes of 4 N-azabicyclo [3.2. 2] nonane thiosemicarbazones derived from acyl diazines. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 2164–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Easmon, J.; Nagi, R.K.; Muegge, B.D.; Meyer, L.A.; Lewis, J.S. 64Cu-azabicyclo [3.2. 2] nonane thiosemicarbazone complexes: Radiopharmaceuticals for PET of topoisomerase II expression in tumors. J. Nucl. Med. 2006, 47, 2034–2041. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Chen, Q.; Ku, X.; Meng, L.; Lin, L.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; et al. A series of α-heterocyclic carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazones inhibit topoisomerase IIα catalytic activity. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 3048–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Y.W.; Liu, G.; Afrasiabi, Z.; Sinn, E.; Padhye, S.; Ma, Y. The cytotoxicity and mechanisms of 1, 2-naphthoquinone thiosemicarbazone and its metal derivatives against MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004, 197, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.T.; Saha, H.H.; Niskanen, L.K.; Salmela, K.T.; Pasternack, A.I. Time course of serum prolactin and sex hormones following successful renal transplantation. Nephron 2002, 92, 735–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartorelli, A.C.; Agrawal, K.C.; Tsiftsoglou, A.S.; Moore, E.C. Characterization of the biochemical mechanism of action of α-(N)-heterocyclic carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazones. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1977, 15, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Ma, Z.Y.; Li, A.; Liu, Y.H.; Xie, C.Z.; Qiang, Z.Y.; Xu, J.Y. Thiosemicarbazone Cu (II) and Zn (II) complexes as potential anticancer agents: Syntheses, crystal structure, DNA cleavage, cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2014, 136, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.N.; Merajver, S.D. Modulation of angiogenesis for cancer prevention: Strategies based on antioxidants and copper deficiency. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 3584–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Bao, L.W.; Merajver, S.D. Tetrathiomolybdate inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis through suppression of the NFκB signaling cascade. Mol. Cancer Res. 2003, 1, 701–706. [Google Scholar]

- Reddi, A.R.; Culotta, V.C. SOD1 integrates signals from oxygen and glucose to repress respiration. Cell 2013, 152, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourdon, P.; Liu, X.Y.; Skjørringe, T.; Morth, J.P.; Møller, L.B.; Pedersen, B.P.; Nissen, P. Crystal structure of a copper-transporting PIB-type ATPase. Nature 2011, 475, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Frezza, M.; Shakya, R.; Cui, Q.C.; Milacic, V.; Verani, C.N.; Dou, Q.P. Inhibition of the proteasome activity by gallium (III) complexes contributes to their anti–prostate tumor effects. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 9258–9265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Agarwal, N.; Mehta, K. Multidrug-resistant MCF-7 breast cancer cells contain deficient intracellular calcium pools. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2002, 71, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhye, S.; Afrasiabi, Z.; Sinn, E.; Fok, J.; Mehta, K.; Rath, N. Antitumor metallothiosemicarbazonates: Structure and antitumor activity of palladium complex of phenanthrenequinone thiosemicarbazone. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 1154–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, I.; Khan, T.; Ahmad, N.; Khan, A.R.; Akhter, Y. Updates on drug designing approach through computational strategies: A review. Future Sci. OA 2023, 9, FSO862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S.No. | Metal | TSC Ligand | Biological Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cu(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) | ethyl (E)-2-cyano-3-(2-((E)-3-ethyl-2- hydroxybenzylidene)hydrazine-1-carbothioamido)-3-(4- ethylphenyl)acrylate | Antifungal, Antibacterial | [15] |

| 2. | Cu(II) | α-Heterocyclic-N4 -Substituted TSCs | Antiproliferative | [16] |

| 3. | Pd(II), Pt(II) | 3,5-diacetyl-1,2,4- triazol mono(4-phenylthiosemicarbazone) | Antiproliferative | [17] |

| 4. | Ru(II) | (E)-2-(1-(5-substituted thiophen-2-yl)ethylidene)-N-substituted hydrazine-1-carbothioamide | Anticancer | [18] |

| 5. | Cd(II) | 4-benzyloxy-benzaldehyde-4-methyl-3-thiosemicarbazone | Anticancer | [19] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hashmi, K.; Satya; Mishra, P.; Veg, E.; Khan, T.; Joshi, S. Computational Studies of Thiosemicarbazone-Based Metal Complexes and Their Biological Applications. Eng. Proc. 2025, 117, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117023

Hashmi K, Satya, Mishra P, Veg E, Khan T, Joshi S. Computational Studies of Thiosemicarbazone-Based Metal Complexes and Their Biological Applications. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 117(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117023

Chicago/Turabian StyleHashmi, Kulsum, Satya, Priya Mishra, Ekhlakh Veg, Tahmeena Khan, and Seema Joshi. 2025. "Computational Studies of Thiosemicarbazone-Based Metal Complexes and Their Biological Applications" Engineering Proceedings 117, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117023

APA StyleHashmi, K., Satya, Mishra, P., Veg, E., Khan, T., & Joshi, S. (2025). Computational Studies of Thiosemicarbazone-Based Metal Complexes and Their Biological Applications. Engineering Proceedings, 117(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117023