Analysis of the Two-Stage Phenomenon and Construction of the Theoretical Model for Metal Hydride Reactors †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Model

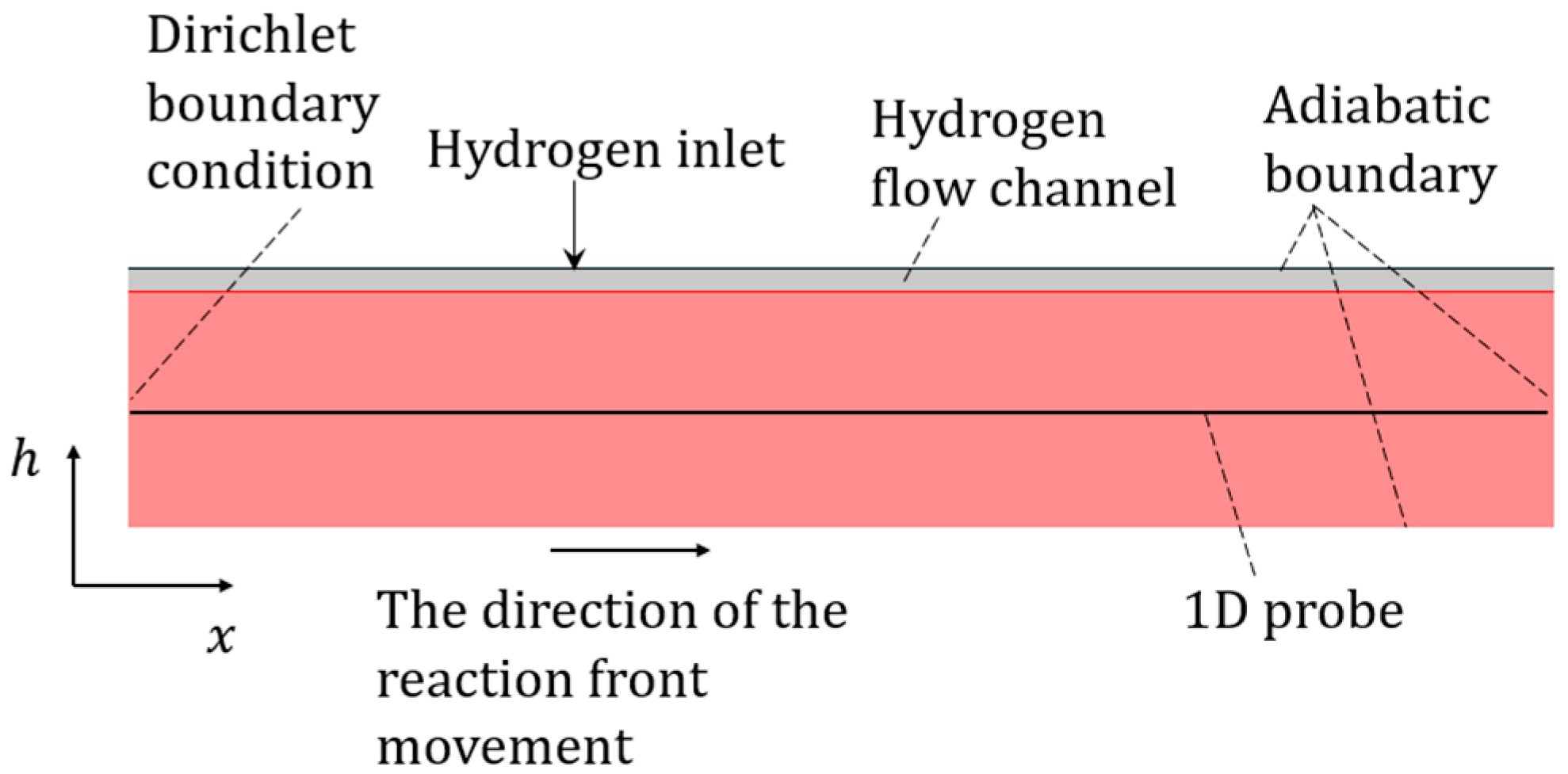

2.1. Geometric Model

2.2. Model Assumptions

- Heat conduction is the dominant mode of thermal transfer in the reactor model, with zero contact thermal resistance between the bed and the wall.

- The thermophysical properties of the metal hydride (MH) and hydrogen remain constant and isotropic.

- Local thermal equilibrium is maintained between hydrogen and the MH bed (porous medium).

- Pressure drop induced by hydrogen flow is neglected.

- Heat dissipation from the outer wall to the environment is ignored.

2.3. Basic Setup

3. Simulation Results and Discussion

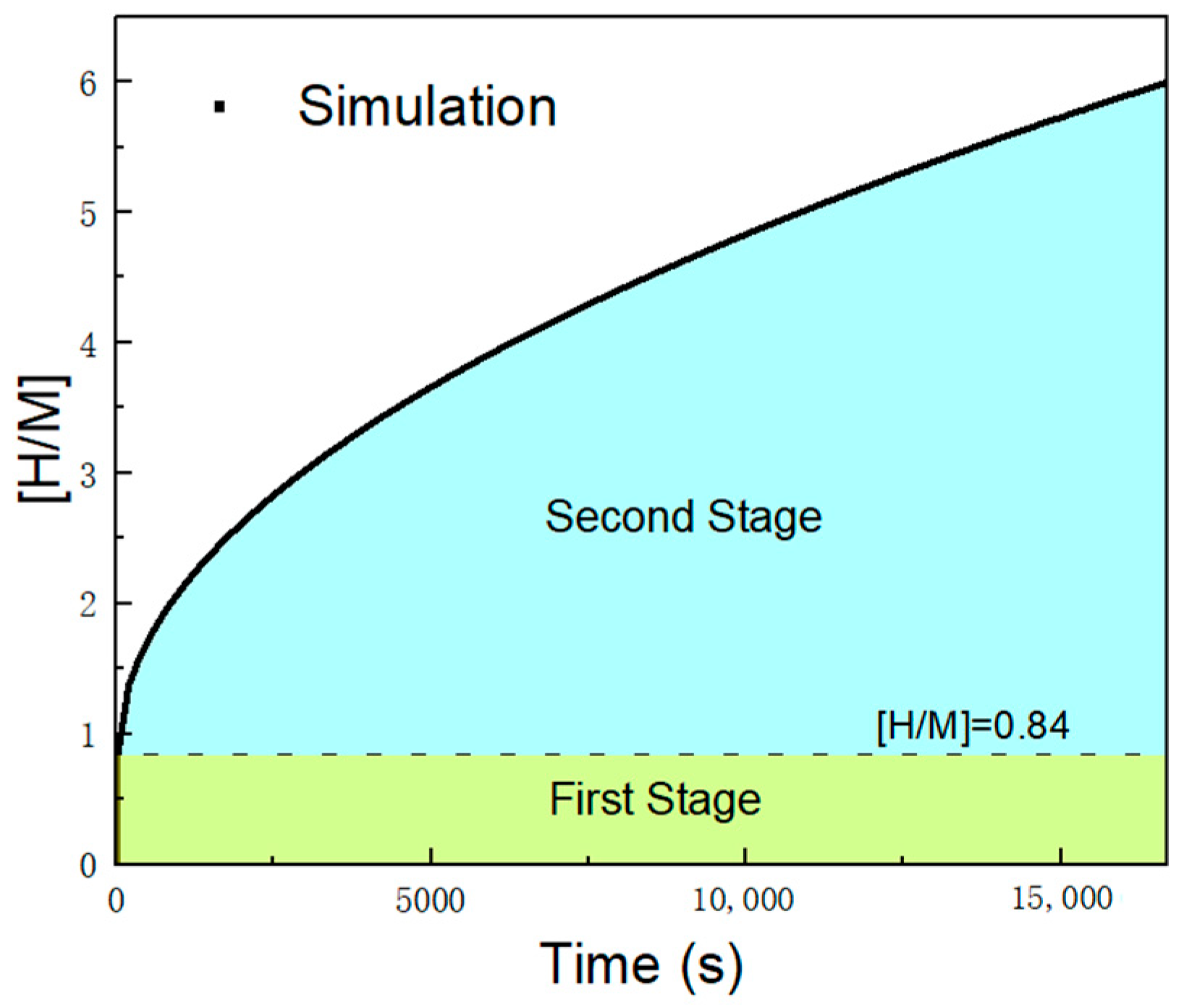

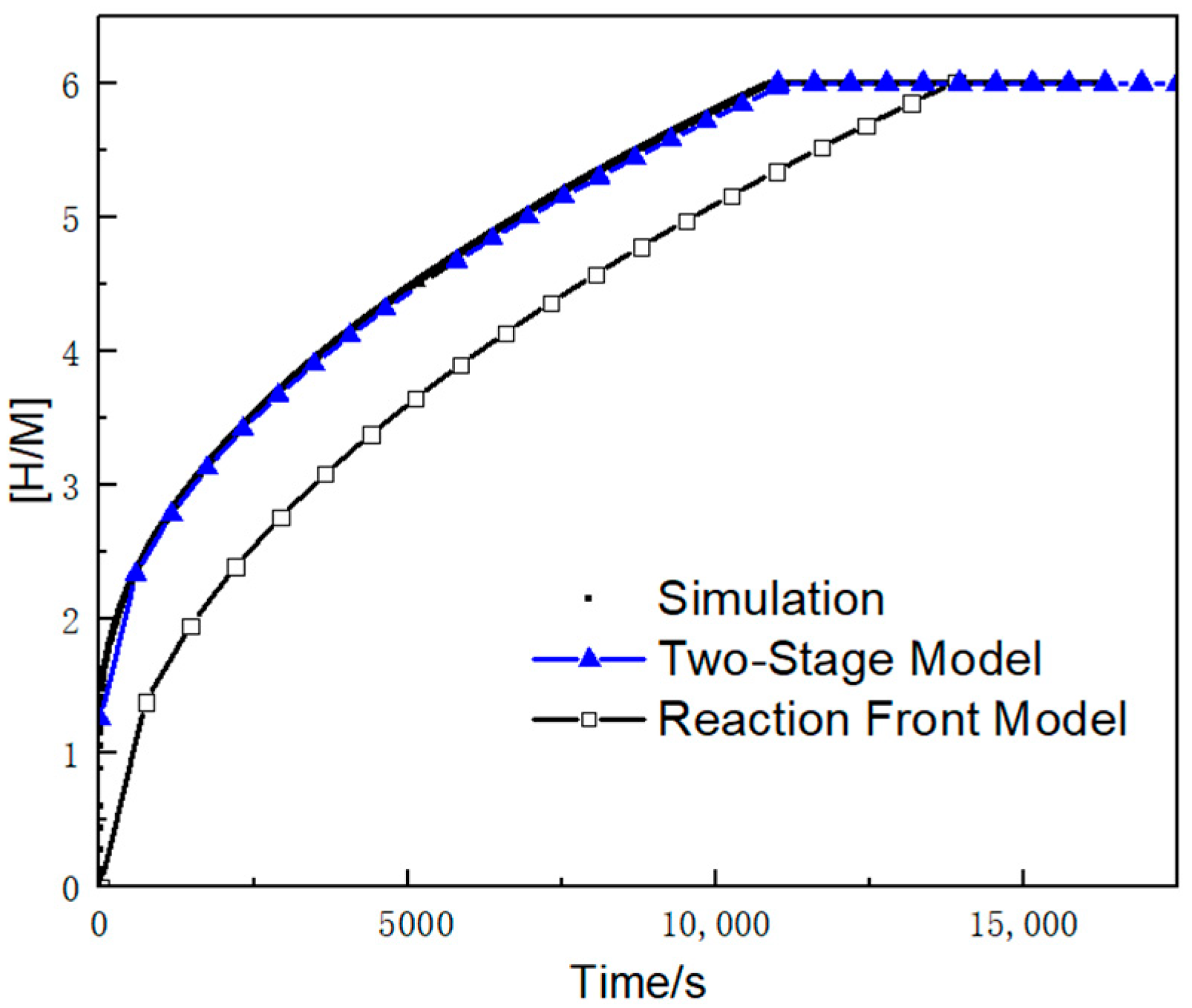

3.1. Variation of the [H/M] Ratio over Time

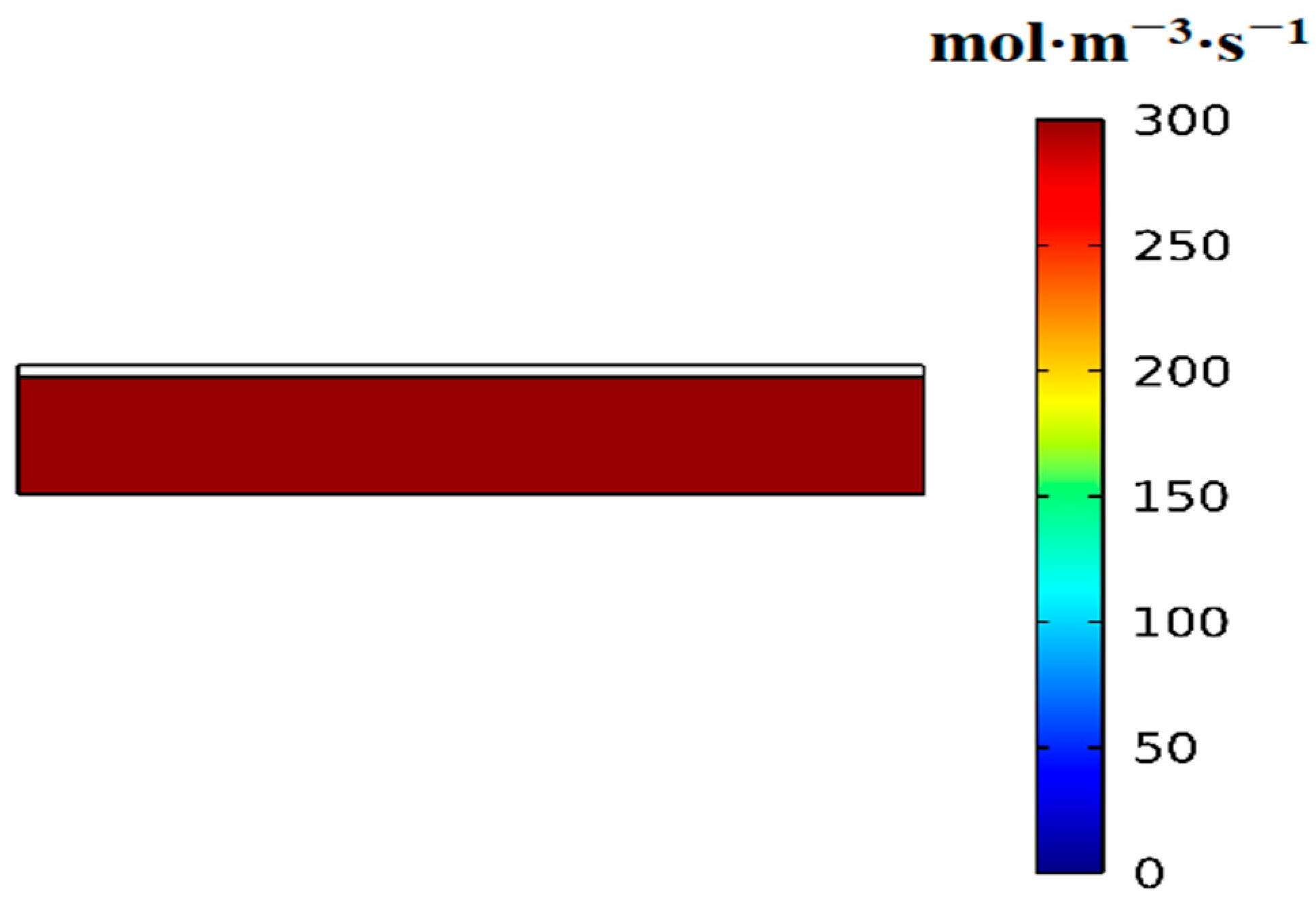

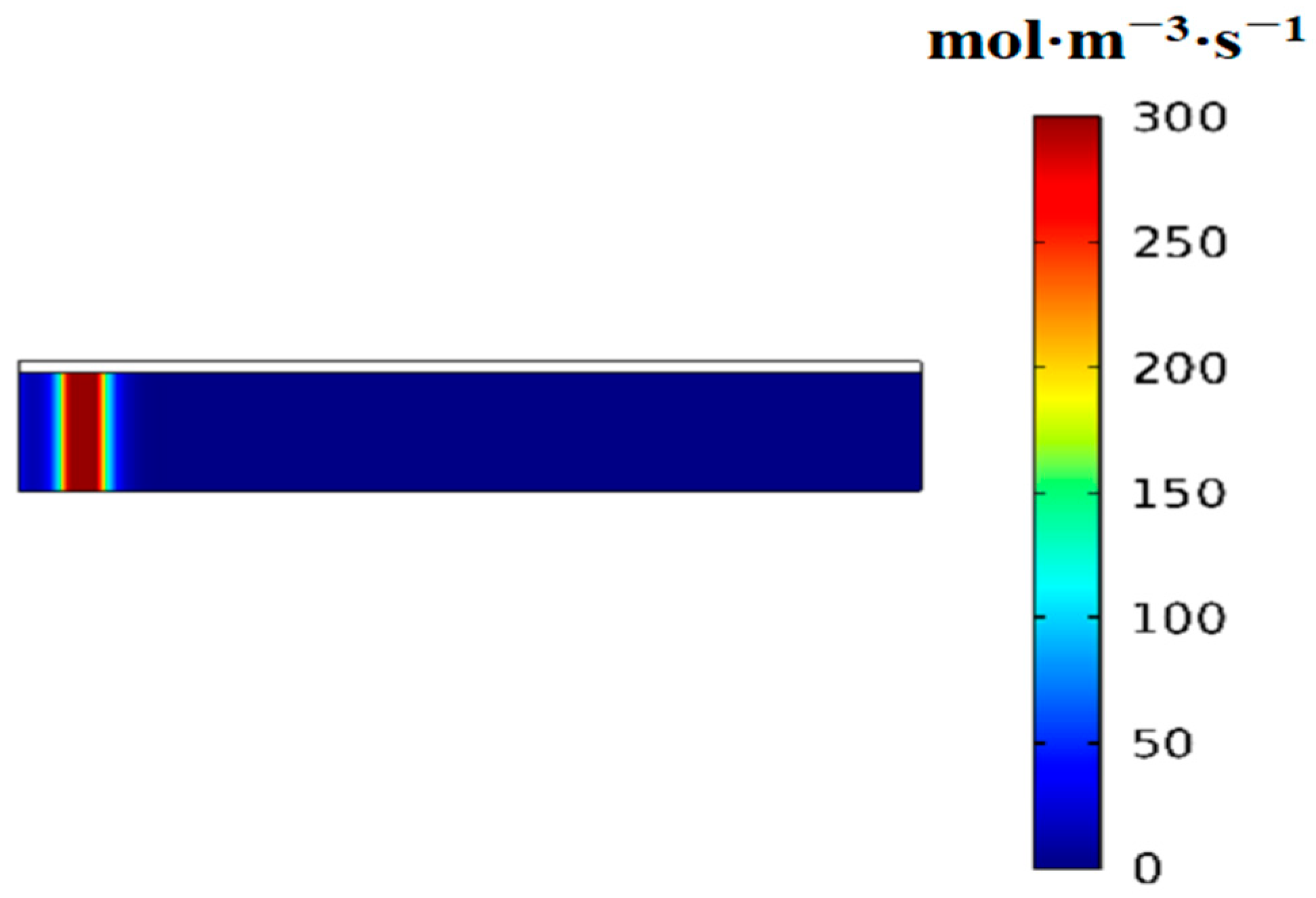

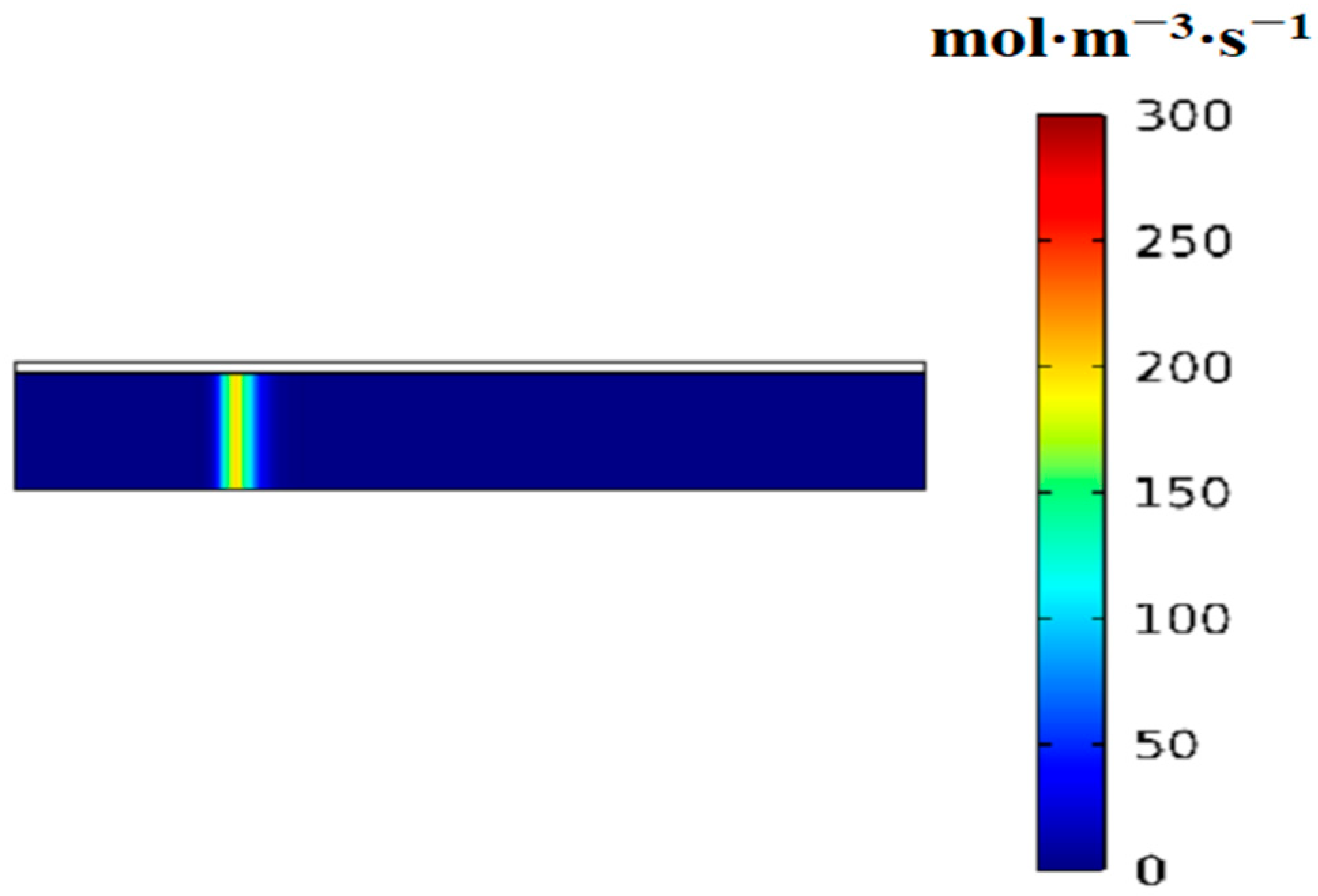

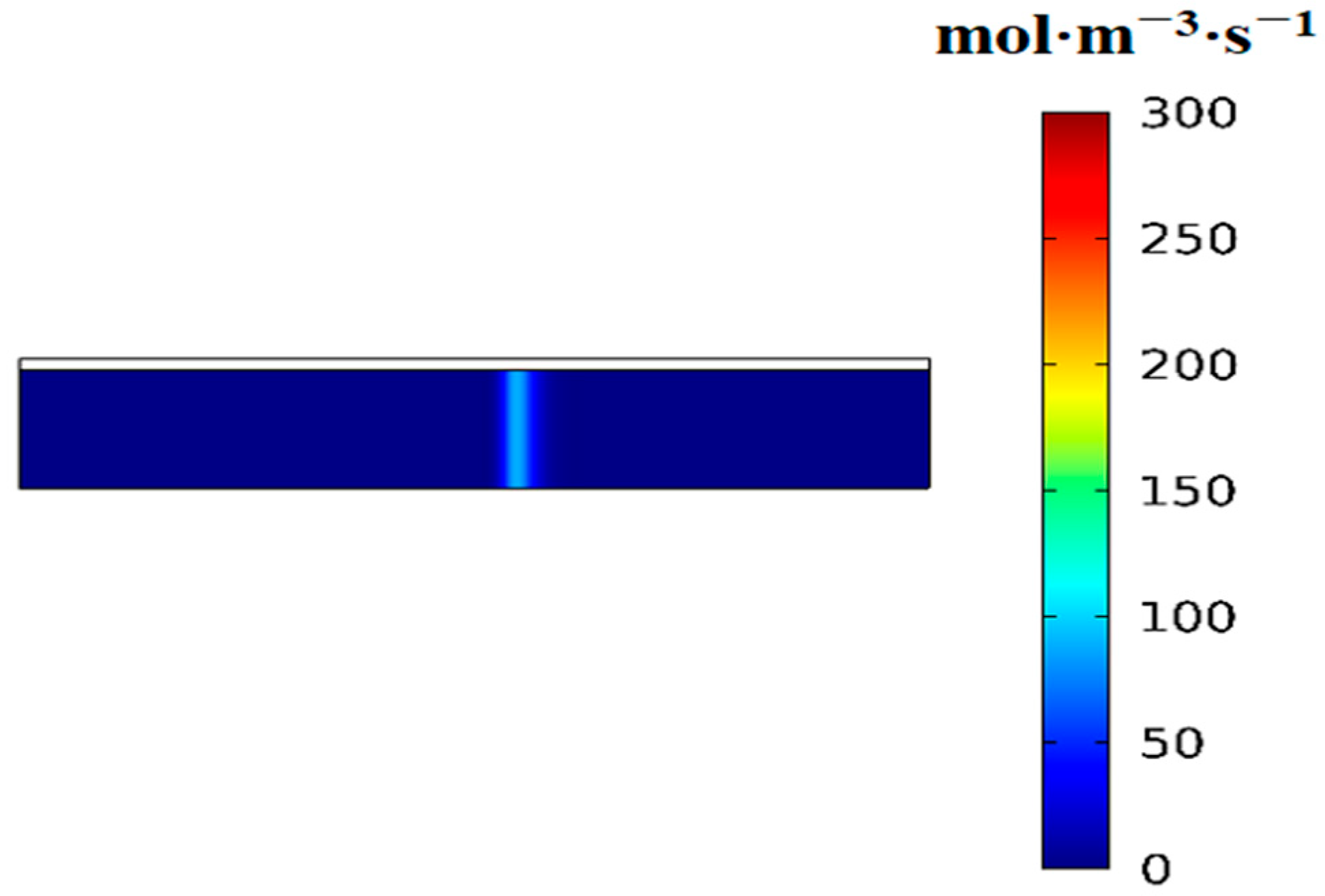

3.2. Variation of the Volumetric Reaction Rate over Time

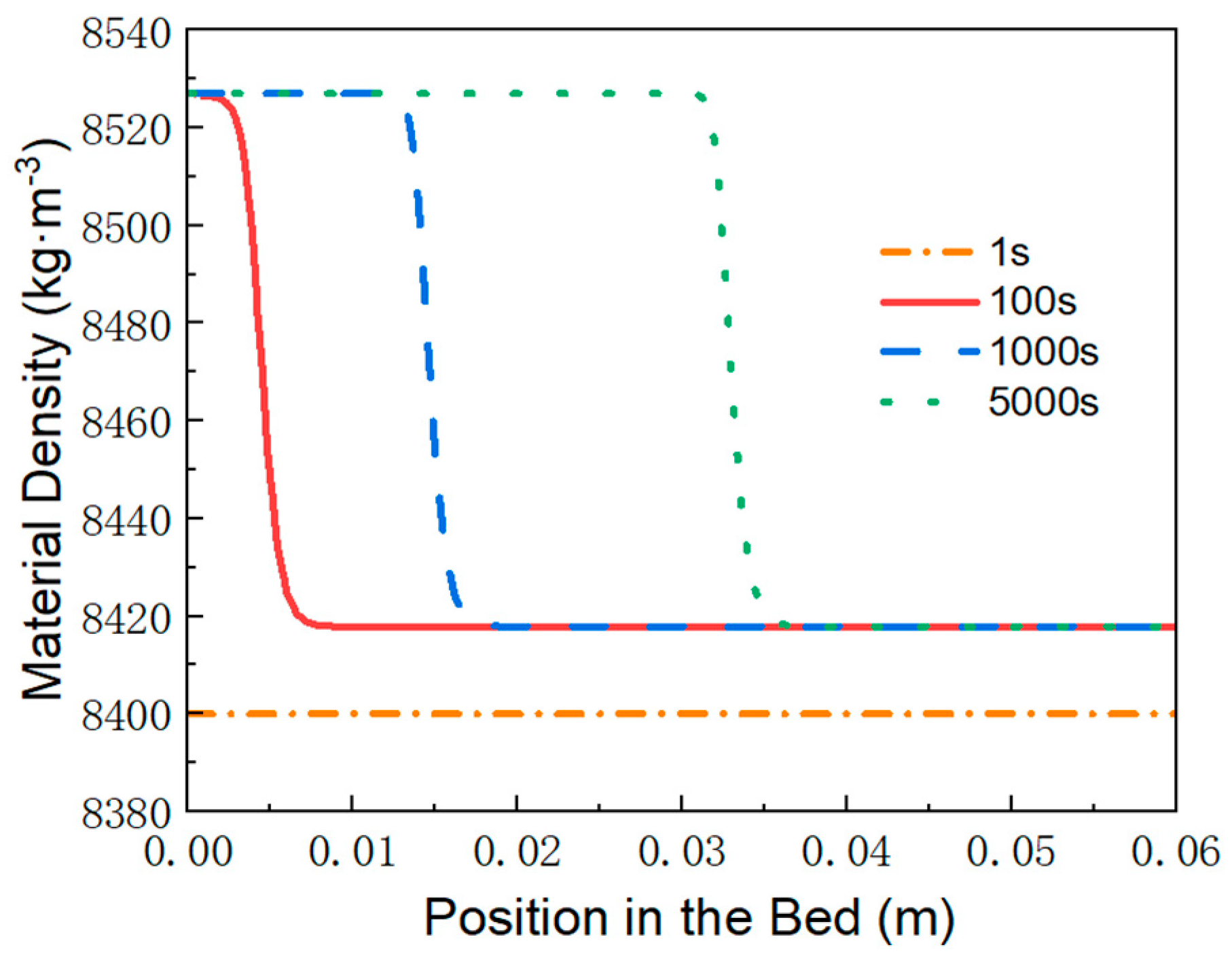

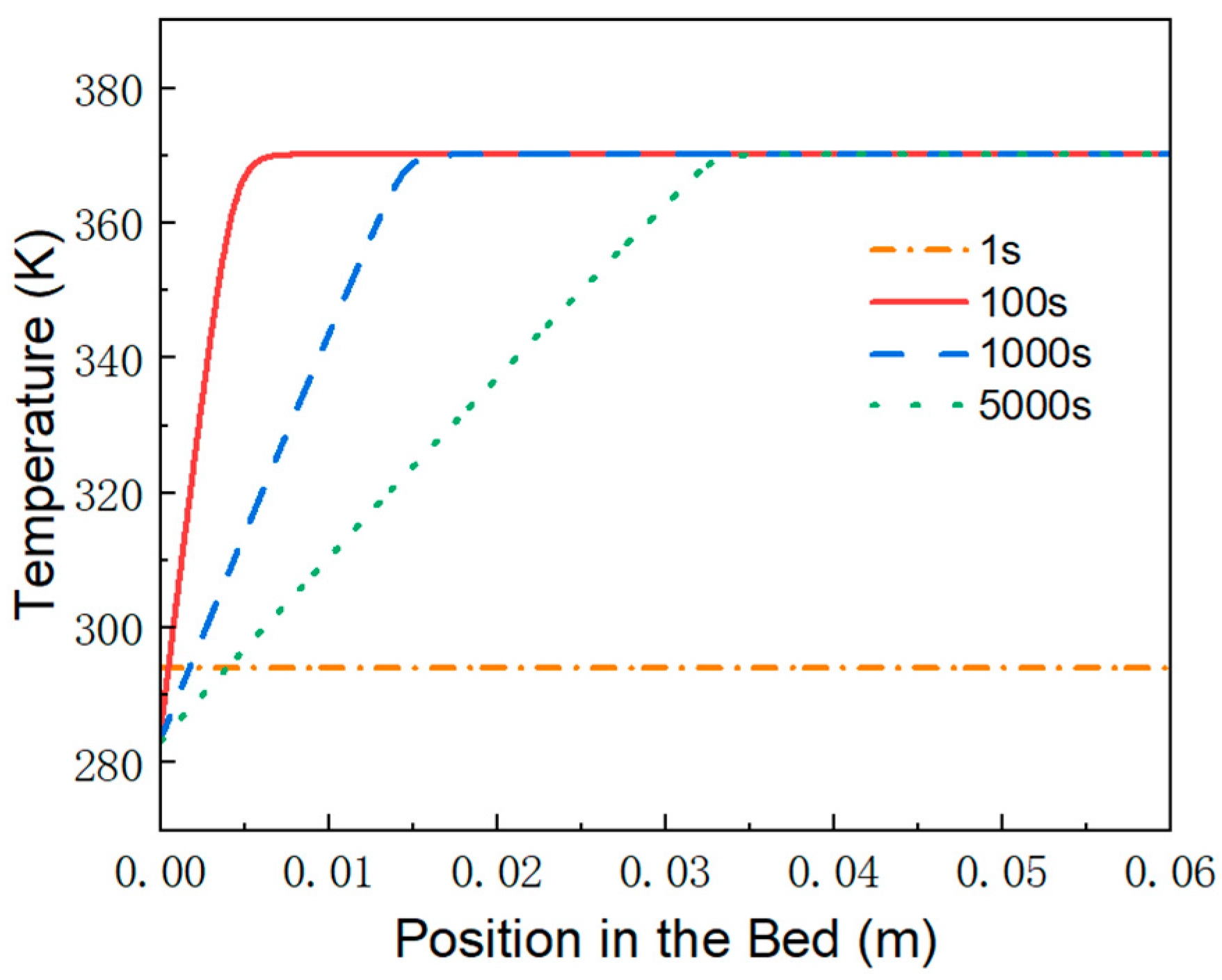

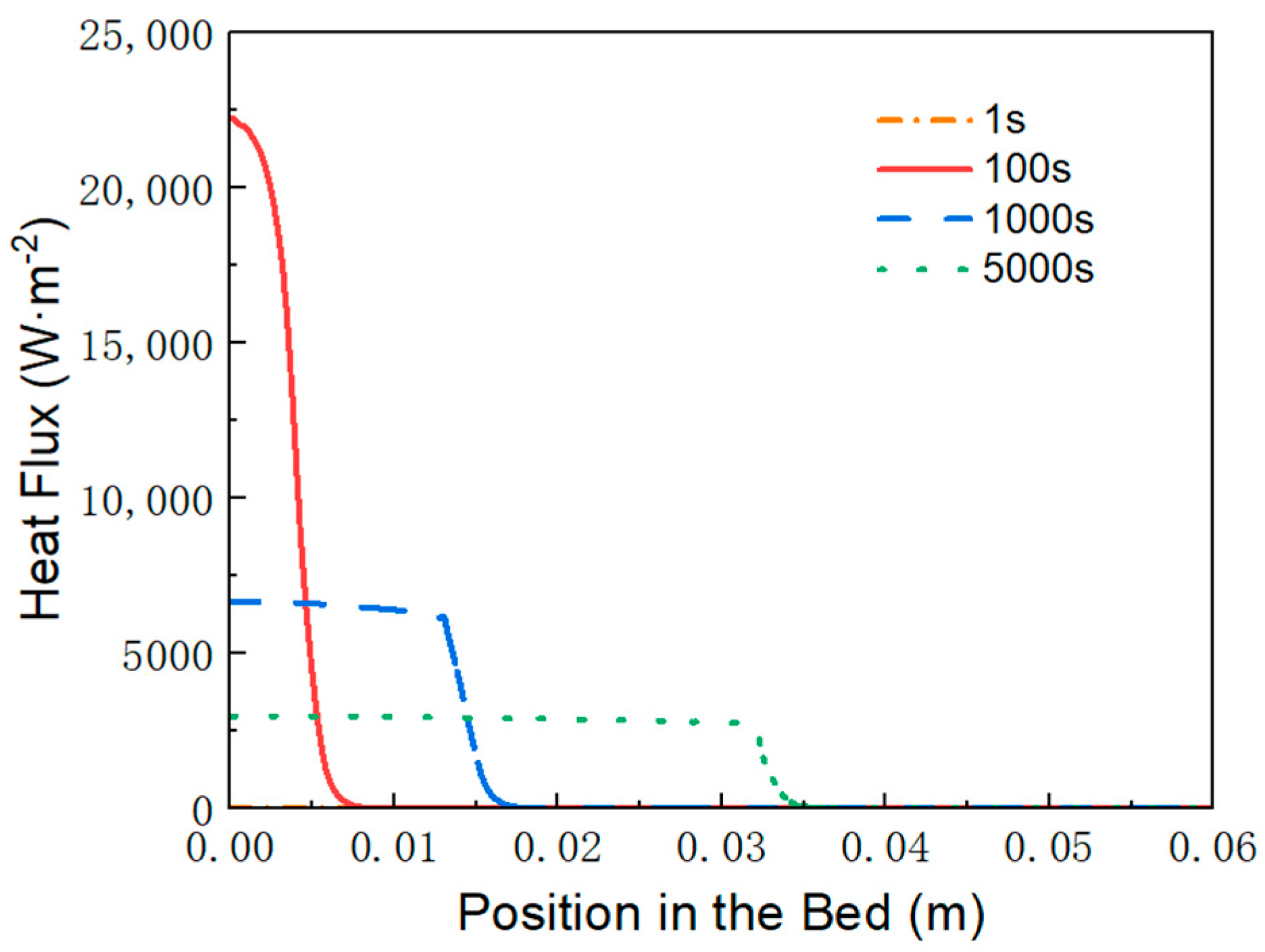

3.3. Variation of Material Density, Temperature and Heat Flux over Time

3.4. Summary

- First item; in regions swept by the reaction front, the hydrogen absorption reaction is complete, and heat transfer occurs with nearly constant heat flux.

- In regions not yet reached by the reaction front, the hydrogen absorption reaction is temporarily stopped, and no heat transfer takes place, resulting in zero heat flux.

- Behind the reaction front, the reaction is complete, and the MH material reaches saturated hydrogen absorption. At any given time, the temperature distribution increases linearly from the wall temperature to the equilibrium temperature at the reaction front.

- Ahead of the reaction front, the reaction is temporarily paused, and the MH material remains in the hydrogen absorption state achieved at the end of the first stage. The bed temperature remains at the equilibrium temperature until the reaction front sweeps through the region.

- At the reaction front, the bed temperature is slightly lower than the equilibrium temperature, enabling an intense and rapid reaction. Most of the heat (or cooling) transferred from the external environment to the bed is supplied to sustain the reaction at the front.

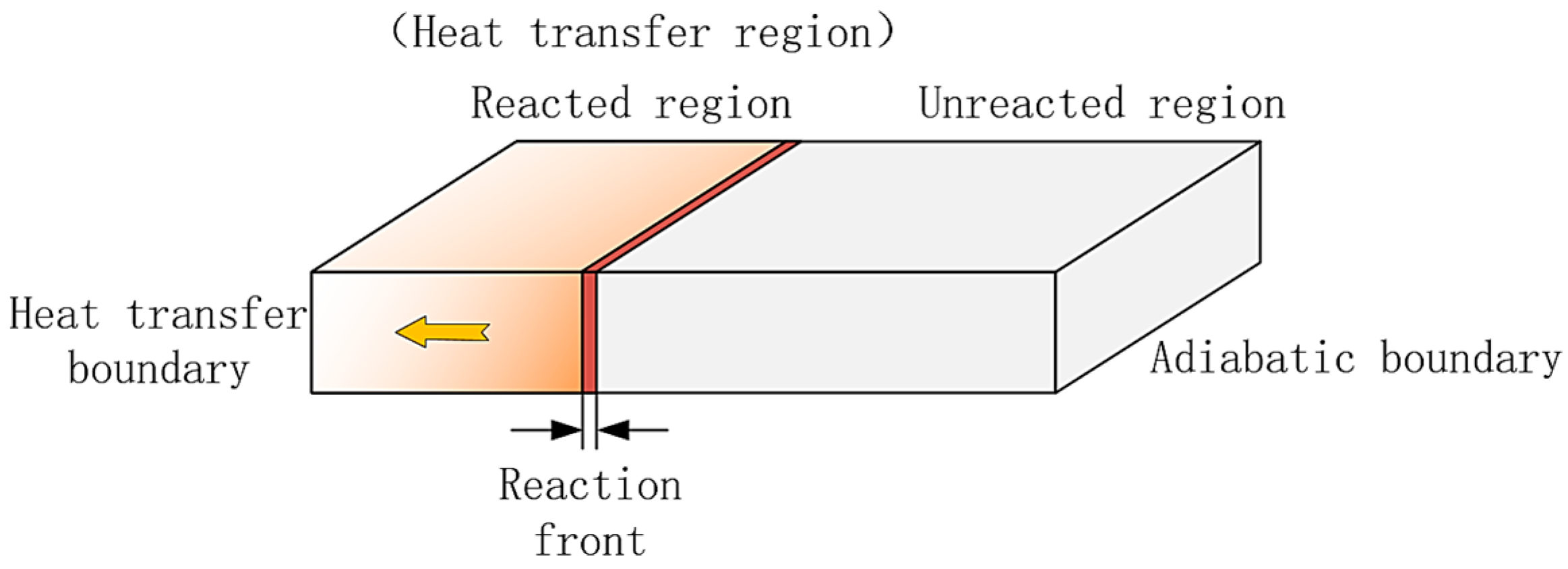

4. MH Reactor Two-Stage Theoretical Model Development

- The duration of the first reaction stage is negligible.

- No heat transfer occurs during the first stage, and the reaction process is governed solely by the initial bed temperature and the hydrogen absorption/desorption pressure.

- At the end of the first reaction stage, the bed temperature equals the reaction equilibrium temperature, and no temperature gradient exists.

4.1. Boundary and Initial Conditions

4.2. Theoretical Derivation

5. Conclusions

- When the initial bed temperature is lower than the reaction equilibrium temperature corresponding to the hydrogen charging pressure, a uniform and rapid hydrogen absorption reaction accompanied by heat release occurs in the MH reactor bed. The temperature rises to the equilibrium level, after which the reaction ceases in most of the bed region. This process is defined as the first reaction stage. At the end of this stage, the product of the reaction fraction per unit volume of the MH material and the reaction enthalpy equals the sensible heat required for the temperature rise of the bed.

- When the temperature of the reactor’s heat exchange wall is lower than the reaction equilibrium temperature, the reaction region progressively advances from the heat transfer boundary toward the adiabatic boundary within the MH reactor. This process is defined as the second reaction stage. In regions swept by the reaction front, the hydrogen absorption reaction reaches saturation, and heat transfer occurs with an almost constant heat flux along the direction of front propagation. In regions not yet reached by the reaction front, heat transfer is negligible, the heat flux remains zero, the hydrogen absorption reaction is temporarily halted, and the hydrogen absorption saturation level of the material remains at the state achieved at the end of the first stage.

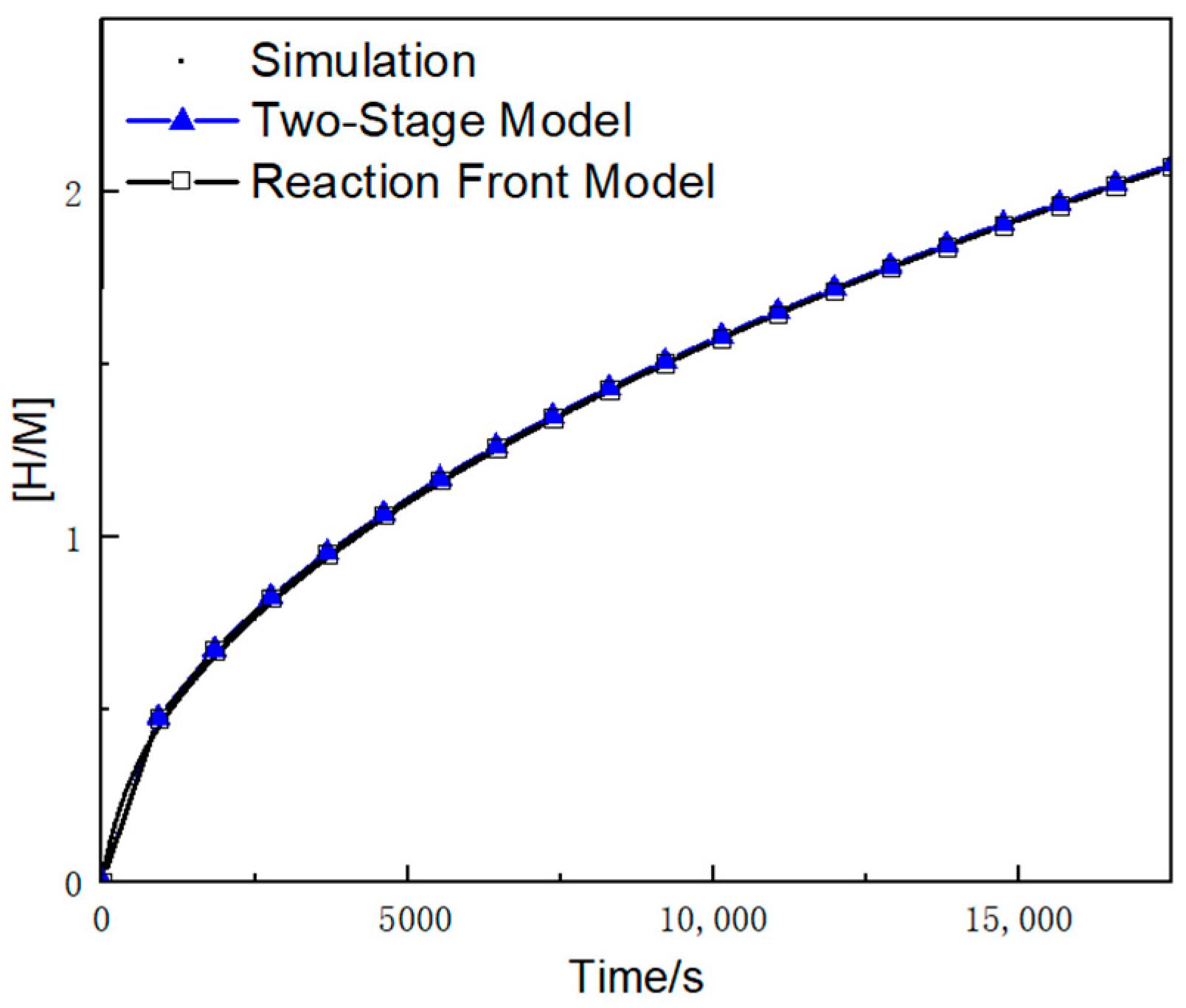

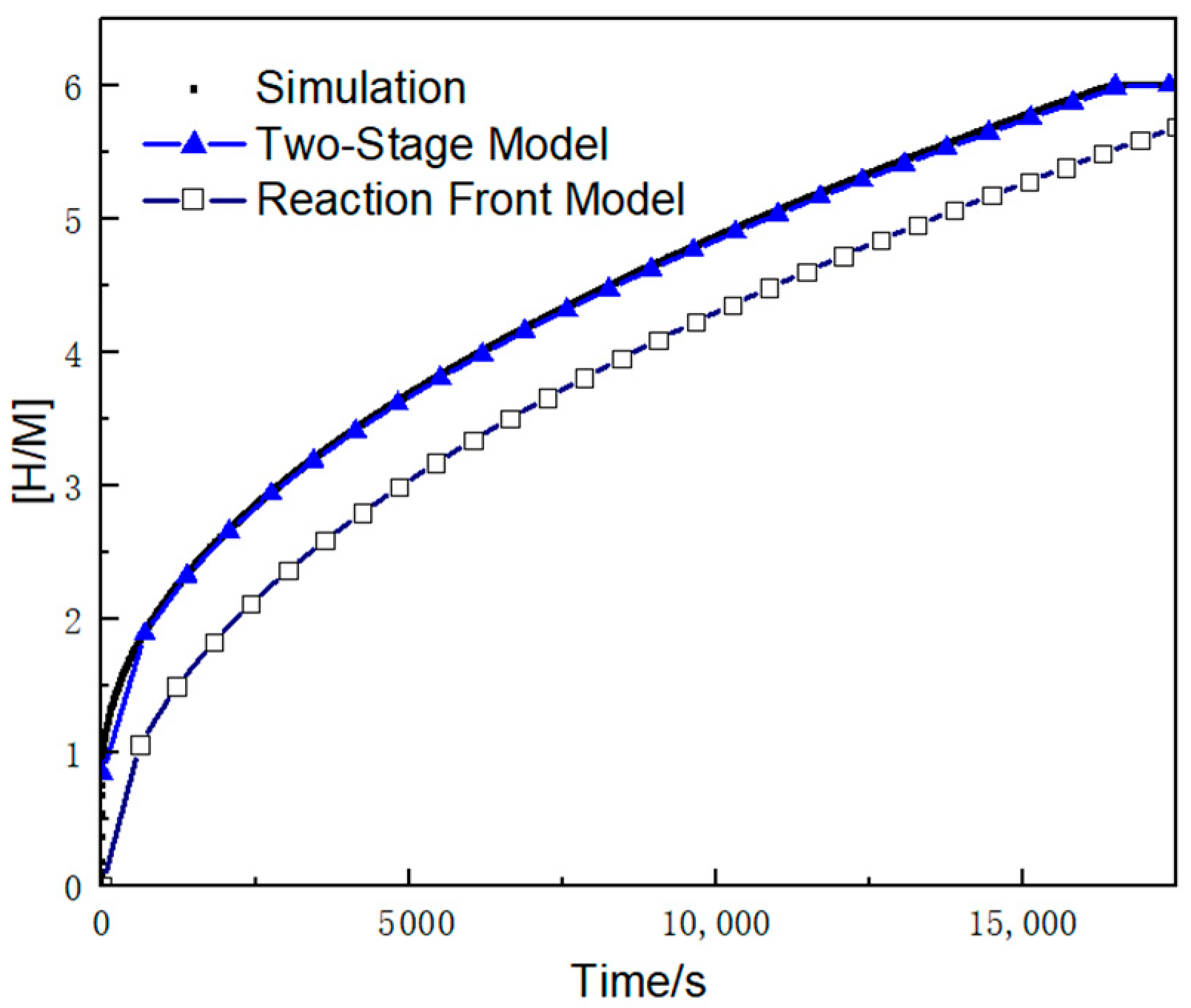

- Based on the assumptions of neglecting the first-stage reaction time and maintaining bed thermal equilibrium, a novel two-stage theoretical model was developed. This model successfully characterizes the internal hydrogen–thermal coupling and reaction progress. Having been numerically validated, the new model achieves a prediction accuracy of 2% for reaction rates, significantly outperforming the original reaction front model’s 25.5% error margin.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ran, R.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Imin, R. Fast design and numerical simulation of a metal hydride reactor embedded in a conventional shell-and-tube heat exchanger. Energies 2024, 17, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visaria, M.; Mudawar, I.; Pourpoint, T.; Kumar, S. Study of heat transfer and kinetics parameters influencing the design of heat exchangers for hydrogen storage in high-pressure metal hydrides. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2010, 53, 2229–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.S.; Yang, W.W.; Zhang, W.Y.; Yang, F.S.; Tang, X.Y. Hydrogen absorption performance of a novel cylindrical MH reactor with combined loop-type finned tube and cooling jacket heat exchanger. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 28100–28115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Ko, J.; Ju, H. Three-dimensional modeling and simulation of hydrogen absorption in metal hydride hydrogen storage vessels. Appl. Energy 2012, 89, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, P.; de Rango, P.; Delhomme, B.; Garrier, S. Various tools for optimizing large scale magnesium hydride storage. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 580, S324–S328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhouri, M.; Bürger, I.; Linder, M. Feasibility analysis of a novel solid-state H2 storage reactor concept based on thermochemical heat storage: MgH2 and Mg(OH)2 as reference materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 20549–20561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-S.; Brinkerhoff, J. Is there a general time scale for hydrogen storage with metal hydrides or activated carbon? Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 12031–12034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-S.; Brinkerhoff, J. Predicting hydrogen adsorption and desorption rates in cylindrical metal hydride beds: Empirical correlations and machine learning. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 24256–24270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dai, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Novaković, J.G.; Yang, F. A novel design for fin profile in metal hydride reactor towards heat transfer enhancement: Considering the limitation of the entransy theory in practical application. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 235, 126221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemni, A.; Nasrallah, S.B.; Lamloumi, J. Experimental and theoretical study of a metal–hydrogen reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1999, 24, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibani, A.; Merouani, S.; Bougriou, C.; Hamadi, L. Heat and mass transfer during the storage of hydrogen in LaNi5-based metal hydride: 2D simulation results for a large scale, multi-pipes fixed-bed reactor. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 147, 118939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Novaković, J.G.; Wu, Z. Analysis of the Two-Stage Phenomenon and Construction of the Theoretical Model for Metal Hydride Reactors. Eng. Proc. 2026, 122, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026122017

Wang J, Yang F, Zhao X, Zhang Z, Novaković JG, Wu Z. Analysis of the Two-Stage Phenomenon and Construction of the Theoretical Model for Metal Hydride Reactors. Engineering Proceedings. 2026; 122(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026122017

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jing, Fusheng Yang, Xinlong Zhao, Zaoxiao Zhang, Jasmina Grbović Novaković, and Zhen Wu. 2026. "Analysis of the Two-Stage Phenomenon and Construction of the Theoretical Model for Metal Hydride Reactors" Engineering Proceedings 122, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026122017

APA StyleWang, J., Yang, F., Zhao, X., Zhang, Z., Novaković, J. G., & Wu, Z. (2026). Analysis of the Two-Stage Phenomenon and Construction of the Theoretical Model for Metal Hydride Reactors. Engineering Proceedings, 122(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026122017