1. Introduction

Public spaces form a fundamental component of the urban environment and play a crucial role in its functioning [

1]. They are not only venues for social interaction and recreation but also influence ecological stability and contribute to the economic development of cities. Their importance has increased significantly in recent decades in response to challenges such as climate change, growing urbanization, and the need for sustainable development [

2]. In major global cities, innovative approaches to transforming public spaces can be observed, aiming to optimize their use to enhance residents’ quality of life and to minimize the negative impacts of urbanization [

3]. This article focuses on analyzing these trends, with an emphasis on the potential for their implementation within the Czech context.

As city centers transform and the demand for sustainable mobility grows, public spaces are becoming an integral part of strategies designed to reduce emissions and promote active modes of transport. For instance, Copenhagen has successfully transformed its public spaces through the development of extensive cycling infrastructure, which has increased the share of cycling in overall mobility and reduced CO

2 emissions [

4]. Similarly, Barcelona has implemented the Superblocks concept, aimed at reducing car traffic and enhancing public space accessibility for pedestrians and cyclists, delivering significant environmental and social benefits [

5]. These approaches demonstrate that effective urban planning can contribute not only to greater ecological stability but also to an improved quality of urban life.

In recent years, it has also become evident that the management of public spaces cannot remain static but must adapt to changes in residents’ behavior and technological progress. Digital technologies such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and smart sensors enable more efficient management of public spaces through real-time data analysis [

6]. Many European cities are already actively utilizing these technologies to optimize public spaces and manage mobility. Integrating these tools into urban infrastructure represents one of the key challenges for the future of urban planning [

7].

Another important aspect of public spaces is their impact on biodiversity and the urban microclimate. The presence of green areas and tree vegetation helps mitigate the urban heat island effect, regulate temperatures, and improve air quality [

8]. Furthermore, natural infrastructure such as green roofs and rain gardens can significantly contribute to rainwater retention and reduce the risk of urban flooding. These ecological functions of public spaces are increasingly being incorporated into sustainable urban development strategies.

2. Material and Methods

The research approach adopted in this article is based on a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, which make it possible to link theoretical knowledge with a systematic comparison of specific empirical data. The chosen methodology reflects the interdisciplinary nature of the topic under study and responds to the need to connect urban planning with principles of sustainable development, environmental aspects, and impacts on mobility.

The first phase of the research process consisted of a systematic review of scholarly literature aimed at mapping the current state of knowledge in the field of public spaces and identifying key theoretical concepts related to sustainable urbanism and urban space management [

9]. The review focused on academic monographs, peer-reviewed scientific articles, studies by international organizations, and strategic documents addressing public space planning, urban ecological stability, climate change adaptation, the development of active mobility, and the use of digital technologies for urban management. The selection of sources took into account their relevance, currency, and scientific quality. This review provided the framework for the subsequent steps of the research process.

The second part of the methodology is based on the targeted selection and detailed analysis of case studies chosen according to clearly defined criteria. The main criterion for including a specific example was the existence of measurable indicators of the impact of urban interventions on transport, the environment, and public space. In addition, attention was paid to the diversity of urban approaches, geographical location, and the potential to use the findings from these cases to formulate recommendations transferable to the Czech context. Within the analytical phase, key variables were identified for each case study, which could be compared using available secondary data. The analysis worked with standardized indicators that allow for comparisons across different urban contexts.

Particular emphasis was placed on the quantitative synthesis of data, which forms the basis of the comparative analysis. For the synthetic component, the method of simple arithmetic mean was applied, which is commonly used for basic statistical estimates. The procedure consisted of aggregating selected numerical values and calculating their mean to obtain an indicative value used to create a hypothetical scenario. This calculation was carried out in accordance with the principles of statistical practice, with the arithmetic mean computed using the generally accepted formula for a point estimate of a population mean [

10]. The resulting average value was then adjusted to reflect the Czech context, taking into account specific local factors that may influence the real impact of the measures.

The arithmetic mean was chosen as a transparent and easily interpretable method suitable for summarizing heterogeneous quantitative data from various case studies. While more complex weighting or regression models could provide deeper insights, they require consistent datasets that were not available in all cases. Therefore, the arithmetic mean serves here as a simplified comparative indicator that enables the synthesis of available results across cities. The limitation of this approach lies in its inability to capture local variability or the influence of contextual factors such as population density, infrastructure quality, or socio-economic characteristics, which must be considered when interpreting the outcomes.

All secondary data were verified for reliability and consistency. To ensure transparency of the calculations, the process of data collection and the conditions for their inclusion in the synthetic analysis were documented. The methodology was designed so that the results could be regarded as a framework estimate with clearly defined validity limits and assumptions that must be respected during interpretation. This approach aligns with standard practice in qualitative and quantitative urban analysis, where the combination of various methods contributes to the validity of conclusions.

The methodological framework also included a reflection on how the synthetic estimates could be further refined and expanded with detailed local data. It is anticipated that verifying hypothetical scenarios will require the application of additional research techniques, such as empirical field data collection, measurement of environmental parameters, monitoring of changes in transport behavior, and the use of spatial analytical tools. The methodology therefore leaves room for adaptation in subsequent research, where dynamic elements such as predictive models or advanced spatial modeling methods can also be integrated.

The entire research process was designed to ensure that its outputs can serve as a basis for strategic public space planning in line with the principles of sustainable development. Although the synthetic analysis is based on data from different geographical and cultural contexts, the principle of comparison and the transfer of good practice is a valid tool for formulating recommendations that can be further tested and adapted to real conditions in Czech cities. The consistent application of a combination of literature review, case studies, and quantitative synthesis ensures a high degree of transparency and professional control throughout the data processing. The overall aim of the analysis is to compare the approaches of these cities and identify key factors for the successful implementation of change.

3. The Importance of Public Spaces for the Urban Environment and Urban Planning of Public Spaces

Public spaces, including squares, parks, pedestrian zones, and recreational areas, play a crucial role within the urban ecosystem. They not only provide spaces for social interaction and relaxation but also significantly contribute to quality of life, public health, and the overall sustainability of the urban environment [

11]. Well-designed public spaces can serve as instruments for reducing socio-economic inequalities by ensuring equal access to recreational and community activities [

12].

Public spaces also promote an active lifestyle. According to research by Coppola et al. (2022), access to parks and open public spaces increases the proportion of residents who engage in regular physical activity by up to 40%. This effect is particularly evident in areas with high-quality infrastructure for cyclists and pedestrians [

13]. A study by Hosseinalizadeh (2022) shows that public spaces with natural features such as trees and water elements help improve mental health and reduce stress levels among residents [

14].

From an ecological perspective, public spaces help mitigate the urban heat island effect, regulate temperatures, and improve air quality. Tree vegetation and green areas function as natural filters, capturing harmful substances and pollutants, thereby contributing to better living conditions in urban environments [

15].

As mentioned above, the planning of public spaces should be based on the principles of multifunctionality, inclusivity, and adaptability. High-quality public spaces should offer opportunities for recreation, community gatherings, and ecological measures that contribute to a city’s resilience to climate change. In contemporary urbanism, the concepts of “smart cities” are increasingly being applied, enabling efficient management of public spaces through digital sensors, artificial intelligence, and green technologies [

16].

One of the key approaches in current urban planning is the use of natural infrastructure. For example, green roofs, rain gardens, and permeable surfaces help reduce the volume of stormwater runoff into sewer systems while simultaneously contributing to the cooling of urban environments [

17].

According to a study by Zhao et al. (2025), well-designed public spaces enhance users’ safety and comfort. Public lighting, high-quality urban furniture, and urban design solutions that consider the needs of different age groups are key factors in determining whether such spaces will actually be used [

18].

4. Analysis of Case Studies—Transformation of Public Spaces in Selected Cities

4.1. Barcelona, Spain [19,20]

Barcelona is one of the leading European cities actively transforming its public space with the aim of reducing traffic congestion and promoting sustainable mobility. The city has introduced the concept of Superblocks (Superilles), which reorganizes the street network to create larger pedestrian zones while minimizing car access. Based on the analysis of the case study, the following conclusions were drawn.

4.1.1. Objectives of the Project

The main objective of the project was to significantly improve the quality of life for residents through the development of extensive public spaces designed for recreation and social interaction. These changes also aim to reduce traffic congestion and greenhouse gas emissions, thereby enhancing not only the city’s environmental sustainability but also its overall livability. A key element of the strategy was the promotion of active mobility—cycling and walking—which not only improves public health but also contributes to smoother traffic flow and reduces pressure on urban infrastructure. Another important aspect is the expansion of green areas, which help regulate temperatures and cool the urban microclimate—an essential measure in combating urban heat islands.

4.1.2. Methods of Implementation

The implementation methods of the project focused primarily on reducing car traffic and transforming public spaces to make them more welcoming for both residents and the environment. Within the Superblocks concept, the street network is restructured so that cars cannot pass through entire blocks, significantly limiting through traffic and encouraging alternative modes of mobility. The closed streets were subsequently transformed into new public spaces, including pedestrian zones, cycle paths, playgrounds, and community gardens, thereby increasing their multifunctionality and accessibility for a wide range of users. An important part of these changes was also the enhancement of biodiversity through tree planting and the expansion of green areas, which not only improve air quality but also help regulate urban temperatures—an essential measure for addressing the adverse impacts of climate change.

4.1.3. Impacts and Results

The implementation of the project has brought significant positive effects both for the environment and for residents’ quality of life. Traffic volume decreased by 40%, which not only resulted in smoother and safer traffic flow but also led to a substantial reduction in CO2 emissions and noise pollution. Air quality also improved, with measurements showing a decrease in nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels by up to 24%, which has a direct impact on public health and the city’s ecological stability. The project has also encouraged active mobility, with a 30% increase in the number of people who regularly walk or cycle in the city. This contributes not only to easing traffic congestion but also to improving residents’ physical fitness. Social interaction has also increased significantly, as the newly created public spaces provide suitable conditions for community activities, neighborhood gatherings, and cultural events—fostering stronger social bonds and enhancing the overall quality of urban life.

4.1.4. Challenges and Constraints

Despite many positive outcomes, the implementation of the project did not come without challenges and limitations. One of the main issues was resistance from drivers, who were initially skeptical about the reduction in car traffic and changes in urban mobility patterns. This resistance stemmed mainly from concerns about reduced accessibility and the need to adapt to new conditions. Another significant challenge was the requirement for substantial infrastructure investment, as the transformation of the street network entailed considerable financial costs—especially for changes to traffic signage, the construction of pedestrian zones and cycle paths, and the introduction of green elements. A key ongoing issue is long-term financial sustainability, as the maintenance and management of newly created public spaces require stable funding sources that need to be secured either through public budgets or innovative financing models. These factors demonstrate that the successful implementation of similar projects is not only a matter of urban planning but also of effectively managing the economic and social dimensions of urban development.

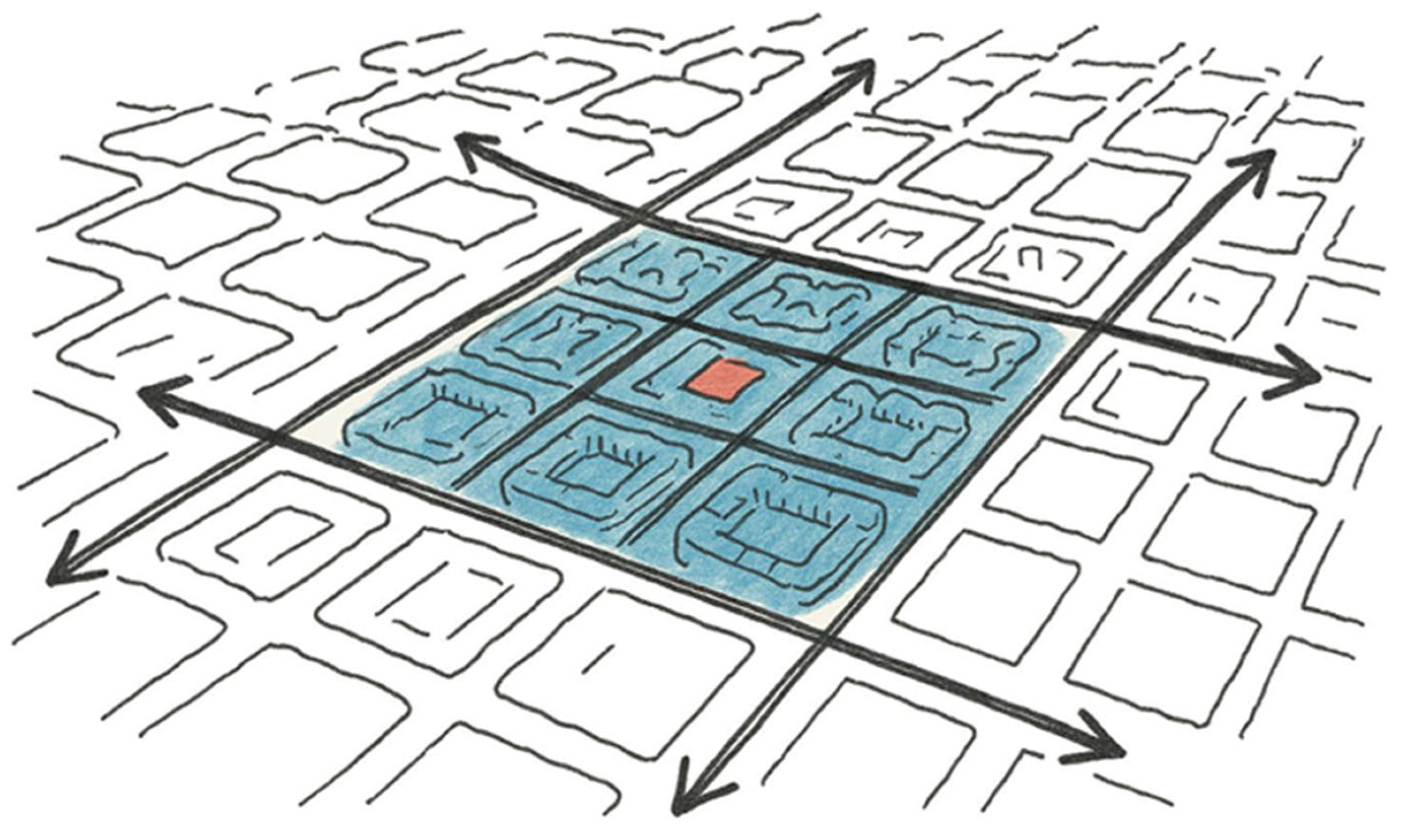

Figure 1 schematically illustrates the concept of Superblocks as applied in Barcelona. It is clearly visible that the original regular street grid is divided into larger units (Superblocks), within which traffic is restricted or calmed, and streets are transformed into spaces for pedestrians, cyclists, and community activities. The black arrows indicate the redirection of through traffic to the perimeter of the Superblock, while the central inner blocks (highlighted in color) remain largely free of car traffic.

4.2. Copenhagen, Denmark [21,22,23]

Copenhagen is considered one of the most bicycle-friendly cities in the world. The city has long invested in infrastructure that supports cycling and active mobility, which has led to a significant transformation of public space. The goal of these changes is to create a healthier, more sustainable, and more efficient urban environment. Based on the analysis of this case study, the following findings were identified.

4.2.1. Objectives of the Project

The main objective of the project was to increase the share of cycling within the city’s overall mobility and to make it the primary mode of transport for as many residents as possible. This shift was also intended to help reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and improve overall air quality. With the growing number of cyclists, it was necessary to ensure their safety and to build infrastructure that would protect both cyclists and pedestrians. An important part of the project therefore involved transforming former parking areas into public spaces, green areas, and recreational zones, thereby not only optimizing the use of urban space but also enhancing the esthetic and ecological value of the urban environment.

4.2.2. Methods of Implementation

To achieve these goals, Copenhagen systematically invested in the development of cycling infrastructure and built more than 400 km of cycle paths, including so-called “bicycle highways” that enable fast and safe travel over longer distances. Another key approach was the integration of cycling into public spaces, which involved converting former car parking areas into cycling zones equipped with benches, greenery, and resting spots. The city also introduced policy instruments to promote cycling, such as tax incentives and benefits for companies that encourage cycling among their employees. These measures were intended to motivate not only individuals but also businesses to prioritize cycling over car use.

4.2.3. Impacts and Results

As a result of the implemented measures, the share of cycling in overall urban transport increased to 41%, meaning that nearly half of the population uses bicycles as their primary mode of transport. This increase in cycling has also had a positive environmental impact, with annual greenhouse gas emissions reduced by 150,000 tons of CO2 due to the decrease in car traffic. Another key benefit has been improved road safety, as the number of accidents involving cyclists has dropped by 17%. These changes have also led to an overall improvement in residents’ quality of life, as access to green and recreational areas has been significantly expanded, providing spaces for relaxation, social interaction, and active leisure.

4.2.4. Challenges and Constraints

Despite the successful implementation of the project, several challenges and limitations emerged that the city had to address. One issue was the occurrence of conflicts between cyclists and pedestrians, especially in densely populated areas where cycle paths became overcrowded and there was insufficient space for all road users. Another significant limitation was the higher maintenance costs, as the city had to regularly invest in repairing cycling infrastructure and ensuring its safety. Moreover, it became clear that changing travel habits is not easy—some Residents still preferred to travel by car and were unwilling to switch to cycling, even under improved conditions. These challenges demonstrate that achieving lasting change requires not only investment in infrastructure but also continuous efforts to raise public awareness and motivate residents to adopt more sustainable modes of transport.

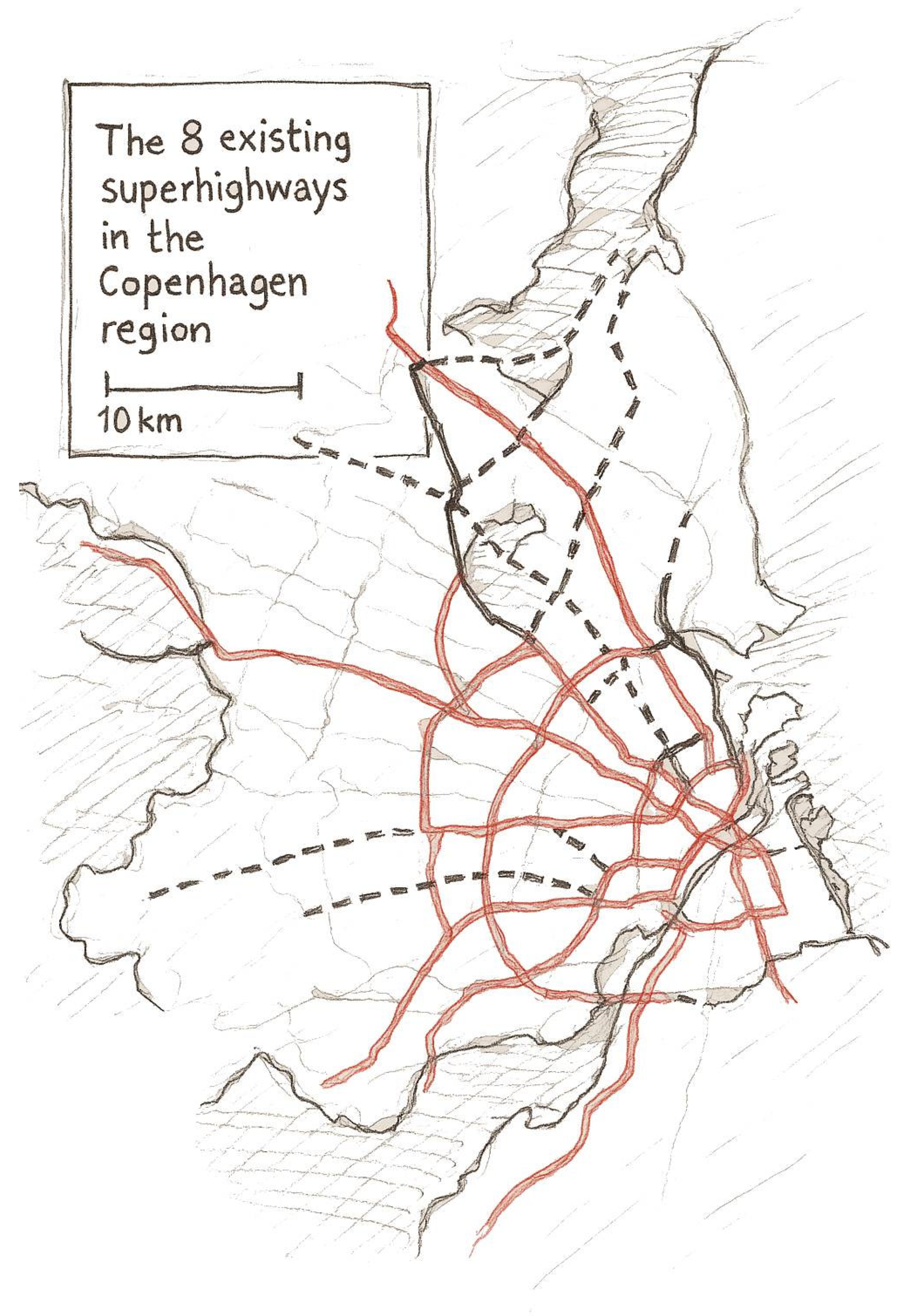

Figure 2 schematically illustrates the network of eight existing cycling superhighways in the Copenhagen region. The red lines show the main backbone routes connecting the city center with surrounding suburban areas over distances of up to several tens of kilometers. This dense network enables safe and convenient cycling even over longer distances and motivates residents to use bicycles as a fully-fledged mode of transport. The dashed lines indicate additional planned connections and links to the regional infrastructure, creating a comprehensive system that supports sustainable mobility throughout the entire metropolitan area.

4.3. Niš, Serbia [24,25,26]

Niš, one of the major cities in Serbia, implemented a project of integrated transport hubs with the aim of reorganizing urban transport and promoting sustainable mobility. The main idea behind the project was to connect electric and shared mobility with public transport in a way that would be more efficient and at the same time more environmentally friendly. Based on the analysis of this case study, the following findings were identified.

4.3.1. Objectives of the Project

The goal of the project was to improve the connections between different modes of transport and to create an efficient system that would enable smoother and more environmentally friendly mobility within the city. A key aspect was also the reduction in car traffic in the city center, which was intended to lower emissions and overall traffic congestion. Another essential element was the promotion of electric vehicles and shared mobility, which allow for more efficient use of transport infrastructure while also helping to reduce air pollution. The project also focused on creating new public spaces around transport hubs with the aim of improving the urban environment and offering residents more opportunities for leisure activities.

4.3.2. Methods of Implementation

To achieve these goals, the city created transport hubs—nodes where passengers can easily switch between buses, trains, shared bicycles, and electric scooters. This integration of different modes of transport enables more efficient mobility and reduces dependence on private cars. The project also supported e-mobility, including the installation of charging stations for electric vehicles and the expansion of the shared electric vehicle fleet. An important step was the improvement of public spaces around the transport hubs, where new green areas, pedestrian zones, and relaxation spaces were created. These measures were aimed not only at promoting environmentally friendly transport but also at improving residents quality of life and making the city more welcoming to pedestrians and cyclists.

4.3.3. Impacts and Results

The implementation of these measures led to a significant reduction in the use of private cars, which decreased by 25%, contributing to smoother traffic flow and reduced congestion. At the same time, the use of shared mobility increased, with the number of users of e-bikes and shared electric scooters rising by 40%, reflecting the growing popularity of alternative modes of transport among residents. Thanks to better integration of public transport, the average commuting time by public transport decreased by 15%, making it a more attractive and efficient option.

4.3.4. Challenges and Constraints

Despite many positive changes, the project did not come without challenges. One of the main issues was the financial cost, as building new transport infrastructure required substantial investment in modernizing existing systems and constructing new facilities. Another key factor was the need to change public behavior, as some residents continued to prefer using private cars and were reluctant to switch to greener alternatives, even when improved conditions were provided. Finally, technological sustainability remains a challenge, as shared mobility systems require regular maintenance and upgrades to stay functional and accessible to the wider public. These challenges demonstrate that the successful implementation of transport innovations requires not only sound planning but also long-term investment and a gradual shift in public transport habits.

5. Results—Comparative Synthetic Assessment of Public Space Transformation Impacts

The aim is to compare the impacts of urban interventions on mobility, air quality, and the use of public space based on data from the case studies (Barcelona, Copenhagen, Niš). It should be emphasized that the following data represent illustrative averages intended only for indicative comparison, not for exact quantification. They must therefore be interpreted as orientation values reflecting general trends rather than precise statistical results. At the same time, the analysis demonstrates a hypothetical estimate of what similar impacts could look like if applied in a Czech urban context. For this purpose,

Table 1 was created with the input data.

For the synthetic estimate, the impact values reported in the case studies (Barcelona, Copenhagen, Niš) were used. For the reduction in car traffic, only two relevant values were taken: −40% (Barcelona) and −25% (Niš). The average was calculated as an arithmetic mean:

For the increase in active or alternative mobility, three values were averaged: +30% (Barcelona, increase in walking/cycling), 41% (Copenhagen, cycling share), and 40% (Niš, shared mobility). The result is an arithmetic mean [

10]:

For the reduction in emissions, specific values are provided from Barcelona (−24% NO2) and Copenhagen (−150,000 tonnes CO2). These values are presented as two separate indicators, as they have different units.

These calculations are purely illustrative. They do not take into account local conditions, demographic factors, or infrastructural differences in Czech cities and serve solely as a general overview for considering the possible transfer of proven approaches. The resulting average provides an indicative estimate of impacts that can be communicated as a hypothetical prediction if cities in the Czech Republic were to apply similar strategies.

The final estimate for a Czech city was developed as an indicative scenario based on the synthetic averaging of the available figures, as described above. The values were methodically adjusted to reflect the specific conditions of Czech cities, such as the structure of transport, the level of cycling infrastructure development, and the realistic potential for change. The estimate therefore suggests that implementing similar measures in pilot areas could lead to a reduction in through car traffic by approximately 30–35%, a reduction in local NO2 emissions by 20–25%, and an increase in the share of active and alternative transport by 30–35%. This scenario serves as an illustrative framework that must be further validated through targeted local data collection, traffic load measurements, and participatory evaluation.

To verify this estimate in practice, it is recommended to carry out a pilot project at the district level, including traffic load measurements, air quality monitoring, and tracking changes in residents’ behavior. The use of GIS analyses, traffic monitoring, and public participation are suitable tools for this purpose. Combining these data will help refine the model and set realistic targets for further development.

5.1. Opportunities for Applying the Case Studies in the Czech Republic and Key Findings

Czech cities face many of the same challenges as Barcelona, Copenhagen, and Niš—whether it is air pollution, traffic congestion, inefficient use of public space, or the need to adapt to climate change. Although every city has its unique characteristics, international experiences offer valuable insights into how to transform urban environments effectively with a focus on sustainability. This section analyzes the potential for applying international case studies in the Czech context and highlights key elements that could help improve the quality of life in Czech cities.

The Superblocks concept, which transforms Barcelona’s street network, could serve as inspiration for Czech cities—particularly Prague, Brno, and Ostrava—where traffic often overloads public space and high-quality public areas are lacking. Restructuring the street network could enable the creation of pedestrian zones and limit through traffic in city centers, for example, in Vinohrady, Smíchov, or the historic parts of Brno. Supporting community life through public events, outdoor markets, or cultural activities would also contribute to a more vibrant and attractive urban environment.

Another key element is the promotion of cycling, which could be implemented through safe routes and dedicated cycling zones similar to those in Barcelona or Copenhagen. The potential for applying the Copenhagen model in the Czech Republic includes expanding protected cycle lanes and creating separated cycling corridors along major city arteries. Another aspect could be the introduction of urban cycle paths connecting suburban areas with city centers—for example, connecting Letňany with the center of Prague. Tax incentives and benefits for cyclists could also play an important role in motivating companies and employers to encourage cycling among their employees.

The project in Niš demonstrates how different modes of transport can be effectively integrated, with an emphasis on electric and shared mobility. This approach could serve as inspiration for modernizing public transport in Czech cities. One of the key opportunities is the creation of multimodal transport hubs that connect urban public transport with cycle paths and shared electric vehicles. Another important aspect is the promotion of e-mobility through the expansion of the charging station network at strategic transport hubs. Smart public transport could include dynamic traffic management systems and real-time vehicle occupancy monitoring, which would increase overall efficiency. It is also essential to improve pedestrian accessibility and ensure that transport infrastructure is well integrated with the surrounding urban environment.

Each of these three case studies offers valuable lessons for improving quality of life in Czech cities. From Barcelona, we can draw inspiration for prioritizing public space, reducing car traffic in specific areas, and promoting pedestrian zones. Copenhagen shows that investment in cycling and safe infrastructure can make a significant contribution to sustainable urban development. Niš demonstrates that smart transport hubs can connect different modes of mobility and increase transport efficiency. For the successful implementation of these strategies, cooperation between municipalities, the state, and the private sector is crucial—together with systematic planning and effective communication with the public.

5.2. The Role of Digital Technologies in the Management of Public Spaces

Digital technologies are playing an increasingly important role in urban planning and the management of public spaces. Thanks to advanced tools such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and Artificial Intelligence (AI), it is now possible to efficiently analyze and manage urban spaces based on data about population movement, space utilization, or air quality. These technologies offer new opportunities to optimize public spaces in real time and to adapt them to the needs of residents and environmental conditions [

6].

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are a key tool for managing and planning public spaces in cities. These systems enable the collection, analysis, and visualization of spatial data, which helps urban planners and decision-makers determine the best use of public space [

27]. GIS can be used for:

Monitoring changes in space use—cities can track which areas are used most frequently and where interventions are needed.

Analyzing traffic flows and population movement—planners can identify problematic areas in the urban infrastructure and propose improvements.

Optimizing the location of public services—GIS helps identify the most suitable sites for new parks, cycle paths, recreational zones, or public buildings.

Assessing environmental impacts—GIS makes it possible to monitor air quality, noise levels, and pollution in different parts of the city.

According to Jazbec (2024), GIS provides an effective way of managing public spaces so that they meet both residents’ needs and environmental requirements. For example, in McDonough County, USA, GIS was used to analyze the accessibility of public parks, which led to the creation of new green spaces in underserved areas [

28].

Artificial Intelligence (AI) brings a revolutionary approach to urban planning by enabling process automation, large-scale data analysis, and predictive modeling [

29]. With AI, it is possible to:

Manage public spaces dynamically—for example, adjusting the intensity of public lighting based on pedestrian movement or automatically regulating urban transport.

Predict traffic congestion and optimize infrastructure—using historical and real-time sensor data, AI can forecast traffic conditions and suggest alternative routes.

Monitor environmental factors—smart sensors connected to AI can analyze air quality, noise levels, or energy consumption and recommend optimization measures.

Support participatory urbanism—AI can process feedback from citizens and automatically propose improvements to public spaces.

According to Moreno-Ibarra et.al (2024), AI can use geographic and video data to analyze how people behave in public spaces. This technology enables city authorities to identify pedestrian congestion areas, for example, and adapt infrastructure accordingly [

30].

Barcelona—analyzed in the previous case study—uses an intelligent sensor system that collects data on air quality, noise levels, traffic intensity, and public space usage. These data are integrated with GIS and AI, enabling dynamic traffic regulation and optimization of public lighting.

For example, Copenhagen uses AI-based predictive models that analyze cyclists’ behavior and forecast future trends in bicycle traffic. This allows the city to allocate cycle lanes more effectively and to optimize shared mobility systems.

Despite the many advantages of GIS and AI, their implementation in public space management also presents several challenges. The introduction of modern GIS and AI systems requires significant investment in infrastructure, data centers, and employee training [

31]. Many cities lack sufficient financial resources to implement these technologies on a large scale. Collecting and analyzing large amounts of data on citizens’ movements also raises concerns about privacy and ethics. It is essential to put protective measures in place to ensure the security of personal data and transparency in their use. Integrating GIS and artificial intelligence into urban systems requires technologically advanced and compatible infrastructure capable of working in synergy with existing data platforms.

Practical examples of the use of data technologies are shown, for example, by Tichý et al. (2023), who proposed a localization method using Bluetooth Low Energy in tunnel systems. Similar principles can also be used to optimize the management of public spaces and furniture, for example, for monitoring occupancy, equipment status or energy consumption management [

32].

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Public spaces and their role in urban planning and sustainable urban development represent a key challenge in contemporary urban design. This article has provided a comprehensive overview of their significance, examined their social, ecological, and economic dimensions, and analyzed concrete examples of successful approaches in an international context. Based on these insights, conclusions have been drawn about effective strategies that can improve the quality of life in urban environments while supporting environmental sustainability.

The analysis shows that public spaces are more than just physical locations—they have a profound impact on the urban ecosystem, foster social cohesion, and create conditions for a healthier lifestyle. They play a significant role in promoting active mobility, as demonstrated by the experience of Copenhagen, where systematic investment in cycling infrastructure has led to lower emissions and a substantial increase in the share of cycling within overall transport. This approach can serve as an inspiration for other cities seeking to reduce traffic burdens and improve air quality.

The research has also revealed that digital technologies play an increasingly important role in the planning and management of public spaces. Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and smart sensors enable more effective decision-making based on real data, contributing to improved traffic flow management, air quality monitoring, and the safety of public spaces. Experiences from Barcelona and Copenhagen demonstrate that integrating digital technologies into urban planning allows cities to optimize space use and adapt it dynamically to residents’ needs.

Although the studies confirm the positive impact of transforming public spaces, their implementation is often limited by two interconnected challenges—financial costs and behavioral change. Upgrading infrastructure and deploying advanced technologies require substantial investment and long-term maintenance funding, which can be achieved through public–private partnerships, grant programs, or phased implementation. At the same time, achieving lasting transformation depends on residents’ willingness to adopt sustainable mobility habits and to use public spaces differently, which requires consistent communication, education, and participatory engagement.

The findings of this research show that applying proven international approaches can significantly improve the quality of public spaces in Czech cities. The experiences of Barcelona, Copenhagen, and Niš can serve as inspiration for implementing similar strategies in Prague, Brno, and other urban areas. The key to success is strategic planning, public participation in decision-making, and the integration of modern technologies into urban governance.

In conclusion, public spaces are an essential component of sustainable urban development, and their transformation is vital for cities to adapt to contemporary environmental and social challenges. The future of urban planning will increasingly rely on a combination of innovative planning methods, technological solutions, and collaboration between civil society, local governments, and experts. If these principles are implemented effectively, public spaces can make a significant contribution to creating cities that are healthier, more inclusive, and more resilient to global change.