Virtual Operation Support Team as a Tool for Threat Mapping and Improving Scenario Modeling in the Field of Road Critical Infrastructure †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Materials

3. Framework for VOST Implementation

3.1. The Role of VOSTs in Crisis Management

3.2. Indicators and Metrics

- The assessed critical infrastructure element is selected and described in detail.

- The element is classified into the appropriate category (group) of infrastructure elements.

- The environment and domain for which the indicators will be defined are determined.

- Specific indicators of the resilience disruption of the given element are identified.

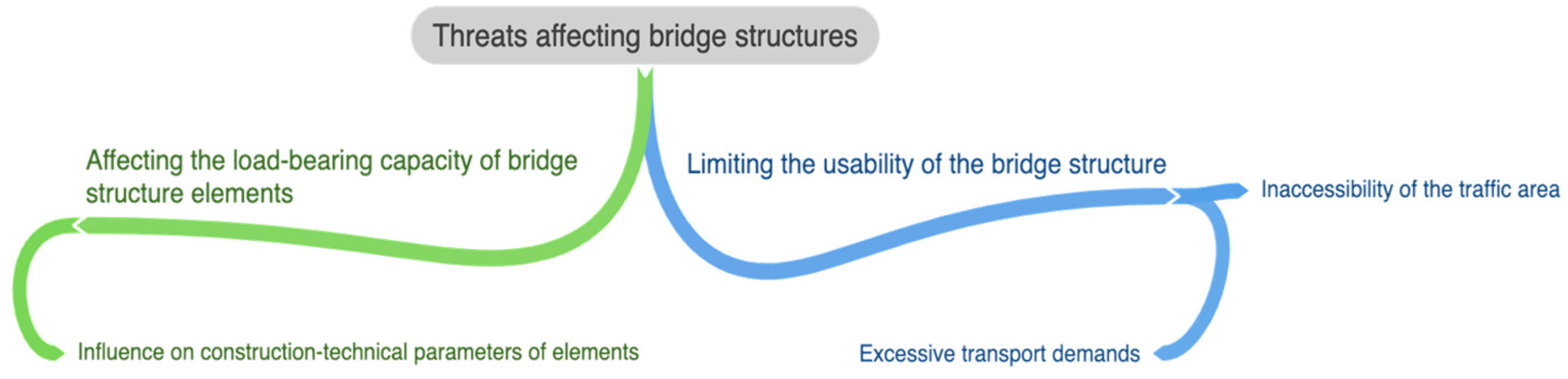

3.3. Threats Affecting Bridge Structures

3.4. Vost Communication Protocols with the Crisis Staff

3.5. Network Metrics

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patrman, D.; Splichalova, A.; Rehak, D.; Onderkova, V. Factors Influencing the Performance of Critical Land Transport Infrastructure Elements. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 40, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlcek, P. Odvodnění Mostních Objektů: Pro Studijní Účely Vysoké Školy Báňské–Technické Univerzity Ostrava, Fakulta Stavební, Katedra Městského Inženýrství; Vysoká Škola Báňská–Technická Univerzita: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2005; ISBN 80-248-0875-7. [Google Scholar]

- Loveček, T.; Straková, L.; Kampová, K. Modeling and Simulation as Tools to Increase the Protection of Critical Infrastructure and the Sustainability of the Provision of Essential Needs of Citizens. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soman, R.K.; Molina-Solana, M.; Whyte, J.K. Linked-Data based Constraint-Checking (LDCC) to support look-ahead planning in construction. Autom. Constr. 2020, 120, 103369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlicek, J. Mosty: Stavba, Údržba, Rekonstrukce; Academia: Praha, Czech Republic, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ryska, O.; Janeckova, H. Impact of Parameters of Critical Road Infrastructure on Crisis Management. In Proceedings of the TRANSBALTICA XV: Transportation Science and Technology, Vilnius, Lithuania, 19–20 September 2024; pp. 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehak, D.; Splichalova, A.; Janeckova, H.; Ryska, O.; Oulehlova, A.; Michalcova, L.; Hromada, M.; Kontogeorgos, M.; Ristvej, J. Critical entities resilience strengthening tools to small-scale disasters. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2025, 49, 100766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, R.; Fiedrich, F. Social Media Analytics by Virtual Operations Support Teams in Disaster Management: Situational Awareness and Actionable Information for Decision-Makers. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 941803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, R.; Thom, D.; Koch, S.; Ertl, T.; Fiedrich, F. VOST: A case study in voluntary digital participation for collaborative emergency management. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cullinane, K.; Liu, N. Developing a model for measuring the resilience of a port-hinterland container transportation network. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 97, 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Lugo, M.A.; Nogal, M.; Morales-Nápoles, O. Estimating bridge criticality due to extreme traffic loads in highway networks. Eng. Struct. 2023, 300, 117172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, L.; Zvakova, Z.; Kampova, K.; Lovecek, T. The Influence of Threat Development on the Failure of the System’s Symmetry. Systems 2021, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliament of the Czech Republic. Act No. 266/2025 Coll., on the Resilience of Critical Infrastructure Entities and Amendments to Related Acts (Critical Infrastructure Act); Collection of Laws of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2025.

- Parliament of the Czech Republic. Act No. 239/2000 Coll., on the Integrated Rescue System and Amendments to Certain Acts; Collection of Laws of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2000.

- Government of the Czech Republic. Government Regulation No. 462/2000 Coll., on the Participation Rules for Crisis Management Authorities; Collection of Laws of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2000.

- Rehak, D.; Senovsky, P.; Slivkova, S. Resilience of Critical Infrastructure Elements and Its Main Factors. Systems 2018, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Regulation (EU) 2024/2557 on the Resilience of Critical Entities; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, F.; Prior, T. Utility of Virtual Operation Support Teams: An International Survey. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2019, 34, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.E. Social Media in Disaster Risk Reduction and Crisis Management. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2013, 20, 717–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliament of the Czech Republic. Act No. 240/2000 Coll., on Crisis Management and Amendments to Certain Acts; Collection of Laws of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2000.

- Veglis, A.; Panagiotou, N. Verifying Social Media Content in Crisis Reporting. In Proceedings of the EJTA Teachers Conference 2018, Thessaloniki, Greece, 18–19 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus, D.; Fathi, R.; Fiedrich, F.; de Walle, B.V.; Comes, T. On the Interplay of Data and Cognitive Bias in Crisis Information Management. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024, 26, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, R.; Schulte, Y.; Schütte, P.M.; Tondorf, V.; Fiedrich, F. Lageinformationen aus den sozialen Netzwerken: Virtual Operations Support Teams (VOST) international im Einsatz. Notfallvorsorge 2018, 49, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, F.; Frings, N.; Kubitza, M.; Wielgosch, T.; Tomczyk, S.; Tutt, L.; Bach, S.; Fiedrich, F. VOST-Methodenhandbuch [Electronic Handbook]. In #Sosmap—Systematische Analyse der Kommunikation in Sozialen Medien zur Anfertigung Psychosozialer Lagebilder in Krisen und Katastrophen; Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe: Bonn, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://wiki.uni-wuppertal.de/!sosmap/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Rehak, D.; Splichalova, A.; Hromada, M.; Lovecek, T.; Hlavaty, R. Využití Indikátorů v Ochraně Kritické Infrastruktury, 1st ed.; Sdružení Požárního a Bezpečnostního Inženýrství: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2022; ISBN 978-80-7385-259-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rehak, D.; Hromada, M.; Ristvej, J. Indication of Critical Infrastructure Resilience Failure. In Proceedings of the Safety and Reliability—Theory and Applications: Proceedings of the 27th European Safety and Reliability Conference (ESREL 2017), Portorož, Slovenia, 18–22 June 2017; Čepin, M., Briš, R., Eds.; CRC Press/Balkema: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehak, D.; Splichalova, A. Application of Composite Indicator in Evaluation of Resilience in Critical Infrastructure System. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology (ICCST), Valeč u Hrotovic, Czech Republic, 7–9 September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehak, D.; Patrman, D.; Foltin, P.; Dvořák, Z.; Skrickij, V. Negative Impacts from Disruption of Road Infrastructure Element Performance on Dependent Subsystems: Methodological Framework. Transport 2021, 36, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhana, K.; Hadipriono, F.C. Analysis of Recent Bridge Failures in the United States. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2003, 17, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Barroca, B.; Bony-Dandrieux, A.; Dolidon, H. Resilience Indicator of Urban Transport Infrastructure: A Review on Current Approaches. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, D.M.M.; Moustafa, I.M.; Khalil, A.H.; Mahdi, H.A. An Assessment Model for Identifying Maintenance Priorities Strategy for Bridges. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2019, 10, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, Z.; Leitner, B.; Rehak, D. Critical Infrastructure Protection Specifications in the Transport Sector. MEST J. 2019, 7, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehak, D.; Hromada, M.; Novotny, P. European Critical Infrastructure Risk and Safety Management: Directive Implementation in Practice. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2016, 48, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maňas, P.; Rotter, T. Vyhodnocení zatížitelnosti mostního provizória TMS podle norem NATO. In Krizové Stavy a Doprava; Institut Jana Pernera, o.p.s.: Lázně Bohdaneč, Czech Republic, 2006; ISBN 80-86530-27-2. [Google Scholar]

- Doming, L.C.P.; Vinaykumar, C.H. Comparison of Load Classification System across the World for Interoperability between Different Countries. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 610–613. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.A.; von Winterfeldt, D. A Framework to Quantitatively Assess and Enhance the Seismic Resilience of Communities. Earthq. Spectra 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaka, L.; Hernantes, J.; Sarriegi, J.M. A Holistic Framework for Building Critical Infrastructure Resilience. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 103, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besinovic, N.; Ferrari Nassar, R.; Szymula, C. Resilience Assessment of Railway Networks: Combining Infrastructure Restoration and Transport Management. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 224, 108538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeckova, H.; Ryska, O. Smart City Resilience. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2024, 111, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P.; Hagedoorn, L.; Bubeck, P. Potential Linkages Between Social Capital, Flood Risk Perceptions, and Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bier, M.; Fathi, R.; Stephan, C.; Kahl, A.; Fiedrich, F.; Fekete, A. Spontaneous Volunteers and the Flood Disaster 2021 in Germany: Development of Social Innovations in Flood Risk Management. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2025, 18, e12933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Afifi, S.; El Khateeb, S.; El Fayoumi, M.A.; ElHusseiny, O.M. Virtual Reality Simulation in Urban Design Processes: Comparative Workflow Assessment and Implementation Outcomes. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titko, M.; Havko, J.; Studena, J. Modelling Resilience of the Transport Critical Infrastructure Using Influence Diagrams. Communications 2020, 22, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.; Sansavini, G. A Quantitative Method for Assessing Resilience of Interdependent Infrastructures. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 157, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudici, H.; Pérez-Fortes, A.P. How Recent Developments in Smart Road Technologies and Construction Materials Can Contribute to the Sustainability of Road Infrastructure. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2022, 28, 02522002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Fan, W.D. Applying Travel-Time Reliability Measures in Identifying and Ranking Recurrent Freeway Bottlenecks at the Network Level. J. Transp. Eng. 2017, 143, 04017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, H.; Fang, Y. Identification of Critical Links in Urban Road Network Based on GIS. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jato-Espino, D.; Pathak, S. Geographic Location System for Identifying Urban Road Sections Sensitive to Runoff Accumulation. Hydrology 2021, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvik, R.; Sagberg, F.; Langeland, P.A. An Analysis of Factors Influencing Accidents on Road Bridges in Norway. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 129, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzynski, M.; Kustra, W.; Okraszewska, R.; Pyrchla, J. The Use of GIS Tools for Road Infrastructure Safety Management. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 26, 00009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, M.G.; Ungureanu, R.D.; Dicu, M. GIS, a Tool for Improving the Road Network Management. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 664, 012103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizky, A.M.; Zahra, A.A.; Astor, Y.; Fauzi, C. Road Maintenance Management Based on Geographic Information System (GIS). Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2023, 13, 2418–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, B.; Work, D.B. Empirically Quantifying City-Scale Transportation System Resilience to Extreme Events. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 79, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, S.; Bullock, D.M.; Vanajakshi, L. Corridor Level Mobility Analysis Using GPS Data. Int. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. Res. 2019, 18, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.C.; Telhado, M.J.; Morais, M.; Barreiro, J.; Lopes, R. Urban Resilience to Flooding: Triangulation of Methods for Hazard Identification in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Key Factors | Roles of the Virtual Operations Support Team |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention | Anticipation, detection, risk management, security measures, innovation processes, and educational and development processes. | Timely identification of trends, verification of signals, and inputs for information campaigns and plan adjustments. |

| Preparedness | Crisis preparedness, robustness, redundancy, material resources, financial resources, human resources, and recovery processes. | Scenario development, digital risk maps, testing of communication channels, and training of both the public and crisis staffs. |

| Response | Responsiveness, detection, security measures, human resources, material resources, and redundancy. | Rapid collection and sorting of information, triage, support for staff decision-making, and coordinated communication with the public, including countering disinformation. |

| Recovery | Renewability, recovery processes, adaptability, financial resources, and innovation processes. | Process analysis, evaluation of experiences (lessons learned), mapping of damages and needs, and proposals for systemic changes. |

| Tool | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional methods (telephone, radio) | Reliable, clear, and direct communication | Limited reach, slow response time | [18,19,39] |

| Social media (Twitter, Facebook) | Fast information, wide reach, real-time updates | Risk of disinformation, need for continuous monitoring | [8,18,19,39,40] |

| VOSTs (virtual operations support teams) | Effective coordination, real-time data | Dependence on technologies, required sufficient digital literacy | [22,41,42,43] |

| Title and Author | Observed Variables | Data Interpretation | Characteristics/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazus–FEMA’s methodology for estimating potential losses from disasters | Flood depth/hazard intensity; object exposure; building typology | Estimation of physical and economic impacts, risk mapping, and prioritization of interventions | Standardized GIS framework for earthquake/flood/cyclone scenarios; output quality strongly depends on the quality of input data |

| Travel-time reliability & PTI [46] | Speed; traffic flow; frequency of congestion; Planning Time Index (PTI) | Identification of bottlenecks and anomalies in time and space on the transport network | Requires detailed operational data; indicates consequences of disruption, not the cause |

| Resilience-based identification of critical roads [45] | Traffic flow; speed; density; network topology OpenStreetMap (OSM)/GIS | Simulation of outages and localization of segments with the highest impact on the network | The network is often simplified due to computational demands; calibration to local operating conditions is necessary |

| GIS identification of critical links [47] | Road density; accessibility; buffer zones; points of interest (POI) | Identification of critical links in the road network based on spatial structure | Static view without real-time data; suitable for preliminary identification of weak points |

| Runoff-sensitive road sections [48] | Total precipitation; surface runoff; digital terrain model; drainage capacity | Localization of segments sensitive to water accumulation during flash rainfall | Requires high-quality elevation data and hydrological calibration; suitable for flash flood scenarios |

| Bridge accident factors [49] | Accident data; bridge parameters; traffic intensity | Identification of bridges with above-average accident rates and risk characteristics | Context-specific method (developed for Norway); requires robust and consistent accident records |

| GIS safety management–roadway geometry [50] | Road curvature; sequence of curves; GPS/ real-time kinematic (RTK) data; speed | Identification of segments with higher risk based on geometric parameters | Field data collection (e.g., using cameras and RTK) is demanding; however, it significantly improves the accuracy of risk assessment for segments |

| Multi-criteria pavement condition assessment [51] | C1 flatness; C2 roughness; C3 bearing capacity; C4 surface degradation | Prioritization of maintenance and indication of the most degraded road sections | Works as part of multi-criteria analysis ELimination Et Choix Traduisant la REalité (ELECTRE), does not provide a complete picture on its own; requires high-quality inventory data |

| UAV imagery + PCI for pavement management [52] | Pavement Condition Index (PCI); heavy vehicle loading; CBR | Localization of pavement surface damage and proposal of repair priorities | Requires the deployment of drones and favorable conditions for imaging; high data resolution significantly increases the accuracy of defect identification |

| City-scale resilience & event detection from GPS data [53] | Travel times; speeds; deviations from expected values | Detection of extraordinary events and evaluation of their impact on mobility at the city-wide scale | Requires a large volume of GPS data; risk of false alarms due to noise deviations |

| Corridor mobility analysis from GPS [54] | Segmentation of the transport corridor; temporal profiles of travel time | Identification of critical periods of mobility decline and detection of sections with significant delays | Dependent on the availability and quality of GPS data; method suitable for operational traffic monitoring |

| Triangulation of flood risk methods [55] | Hydrological data; topographic data; object exposure; infrastructure | Combined flood risk indicators and identification of sensitive network sections | Integration-intensive method; its advantage is the synthesis of multiple data sources for a more robust identification of endangered sites |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryska, O.; Gamonova, P. Virtual Operation Support Team as a Tool for Threat Mapping and Improving Scenario Modeling in the Field of Road Critical Infrastructure. Eng. Proc. 2025, 116, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116033

Ryska O, Gamonova P. Virtual Operation Support Team as a Tool for Threat Mapping and Improving Scenario Modeling in the Field of Road Critical Infrastructure. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 116(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116033

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyska, Ondrej, and Patricie Gamonova. 2025. "Virtual Operation Support Team as a Tool for Threat Mapping and Improving Scenario Modeling in the Field of Road Critical Infrastructure" Engineering Proceedings 116, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116033

APA StyleRyska, O., & Gamonova, P. (2025). Virtual Operation Support Team as a Tool for Threat Mapping and Improving Scenario Modeling in the Field of Road Critical Infrastructure. Engineering Proceedings, 116(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116033